Background: Foxm1 is up-regulated in prostate adenocarcinomas and its expression correlates with the poor prognosis.

Results: Conditional depletion of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells inhibits tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

Conclusion: Foxm1 expression in prostate epithelial cells is essential for prostate carcinogenesis in mouse models.

Significance: Foxm1 may play a key role in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer in human patients.

Keywords: Cancer, Epithelial Cell, Prostate Cancer, Transcription Factors, Transgenic Mice, 11β-Hsd2, Forkhead Transcription Factor FoxM1, Prostate Epithelial Cells

Abstract

The treatment of advanced prostate cancer (PCa) remains a challenge. Identification of new molecular mechanisms that regulate PCa initiation and progression would provide targets for the development of new cancer treatments. The Foxm1 transcription factor is highly up-regulated in tumor cells, inflammatory cells, and cells of tumor microenvironment. However, its functions in different cell populations of PCa lesions are unknown. To determine the role of Foxm1 in tumor cells during PCa development, we generated two novel transgenic mouse models, one exhibiting Foxm1 gain-of-function and one exhibiting Foxm1 loss-of-function under control of the prostate epithelial-specific Probasin promoter. In the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate (TRAMP) model of PCa that uses SV40 large T antigen to induce PCa, loss of Foxm1 decreased tumor growth and metastasis. Decreased prostate tumorigenesis was associated with a decrease in tumor cell proliferation and the down-regulation of genes critical for cell proliferation and tumor metastasis, including Cdc25b, Cyclin B1, Plk-1, Lox, and Versican. In addition, tumor-associated angiogenesis was decreased, coinciding with reduced Vegf-A expression. The mRNA and protein levels of 11β-Hsd2, an enzyme playing an important role in tumor cell proliferation, were down-regulated in Foxm1-deficient PCa tumors in vivo and in Foxm1-depleted TRAMP C2 cells in vitro. Foxm1 bound to, and increased transcriptional activity of, the mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter through the −892/−879 region, indicating that 11β-Hsd2 was a direct transcriptional target of Foxm1. Without TRAMP, overexpression of Foxm1 either alone or in combination with inhibition of a p19ARF tumor suppressor caused a robust epithelial hyperplasia, but was insufficient to induce progression from hyperplasia to PCa. Foxm1 expression in prostate epithelial cells is critical for prostate carcinogenesis, suggesting that inhibition of Foxm1 is a promising therapeutic approach for prostate cancer chemotherapy.

Introduction

Development of cancer is a multistep process involving gain-of-function mutations in oncogenes leading to increased cell proliferation and survival (1). Cancer progression also requires inactivation of tumor suppressor genes that arrest cell proliferation in response to oncogenic stimuli (2). In normal prostate epithelium, the relatively low rate of cell proliferation is balanced by a low rate of apoptosis (3). In contrast, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN)3 and early invasive carcinomas are characterized by an increase in the proliferation rate, whereas advanced and/or metastatic prostate cancers also display a significant decrease in the rate of apoptosis. Altered cell-cycle control is therefore likely to play a role in progression of disease, whereas deregulation of apoptosis may be more important for advanced carcinoma. Published studies have demonstrated significant activation of the PI3K/Akt and ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in prostate carcinomas (4, 5).

The Foxm1 transcription factor is a member of the Forkhead box (Fox) family of transcription factors and broadly expressed in actively dividing cells (6–9). Activation of the MAPK signaling pathway drives cell cycle progression by regulating the temporal expression of cyclin regulatory subunits that activate their corresponding cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdk) through complex formation. Cdk-cyclin complexes phosphorylate and activate a variety of cell cycle regulatory proteins, including Foxm1 (1, 2, 10). Activated ERK directly phosphorylates the Foxm1 protein, contributing to its transcriptional activation (11). In proliferating cells, expression of the Foxm1 is induced during the G1/S-phase of the cell cycle and its expression continues throughout mitosis. Foxm1 directly stimulates the transcription of genes essential for progression into DNA replication and mitosis, including Cyclin B1, Cdc25B phosphatase, Aurora B kinase, and Polo-like kinase 1 (12). Foxm1 was shown to be essential for diminishing nuclear accumulation of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, proteins that inhibit Cdk2 activity in G1 (13–15). Expression of the alternative reading frame (ARF) tumor suppressor is induced in response to oncogenic stimuli (2). ARF prevents aberrant cell proliferation by targeting Mdm2 to nucleolus and increasing stability of the p53 tumor suppressor (16, 17). The ARF protein also targets E2F1, c-Myc, and Foxm1 transcription factors to the nucleolus, thus preventing the transcriptional activation of their target genes (18, 19). Expression of the ARF protein is lost in a variety of tumors through DNA methylation and silencing of the ARF promoter region (2, 17).

Prostate cancer (PCa) continues to be the most common malignancy diagnosed in American men and the second leading cause of male cancer mortality (20). Major efforts have been directed toward identifying early detection and prognostic markers for PCa. In contrast, significantly less research has been devoted to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying PCa pathogenesis. Identification of genes regulating the initiation and/or progression of PCa would provide novel targets for diagnosis and treatment of human PCa. The transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) recapitulates multiple stages of human PCa by using the probasin promoter to drive the expression of the SV40 virus large T antigen (Tag) oncoprotein specifically in prostate epithelial cells (21, 22). T antigen inactivates the tumor suppressor proteins retinoblastoma (Rb), p53, and PP2A serine/threonine-specific phosphatase (23), effectively inducing prostate tumors in adult mice. At early stages, TRAMP mice develop prostate epithelial cell hyperplasia and PIN, that progress to histopathologically invasive PCa (21, 24). Both the reproducibility and progressive nature of PCa development in the TRAMP mouse model has provided a greater understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in PCa development and progression (25).

Increased expression of Foxm1 is observed in tumor cells, inflammatory cells, and stromal cells of numerous human tumors, implying that Foxm1 plays an important role in tumor progression (reviewed in Refs. 12 and 26–31). Indeed, overexpression of Foxm1 using the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter accelerated tumor growth induced by SV40 T large/small t antigens (29). However, given that expression of the Rosa26-Foxm1 transgene was ubiquitous, the specific requirements for Foxm1 in different cell types of PCa remain unknown. The present study was designed to determine the cell autonomous role of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells during formation of prostate adenocarcinomas in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Transgenic Mice

Loss-of-Function of Foxm1 in Prostate Epithelium

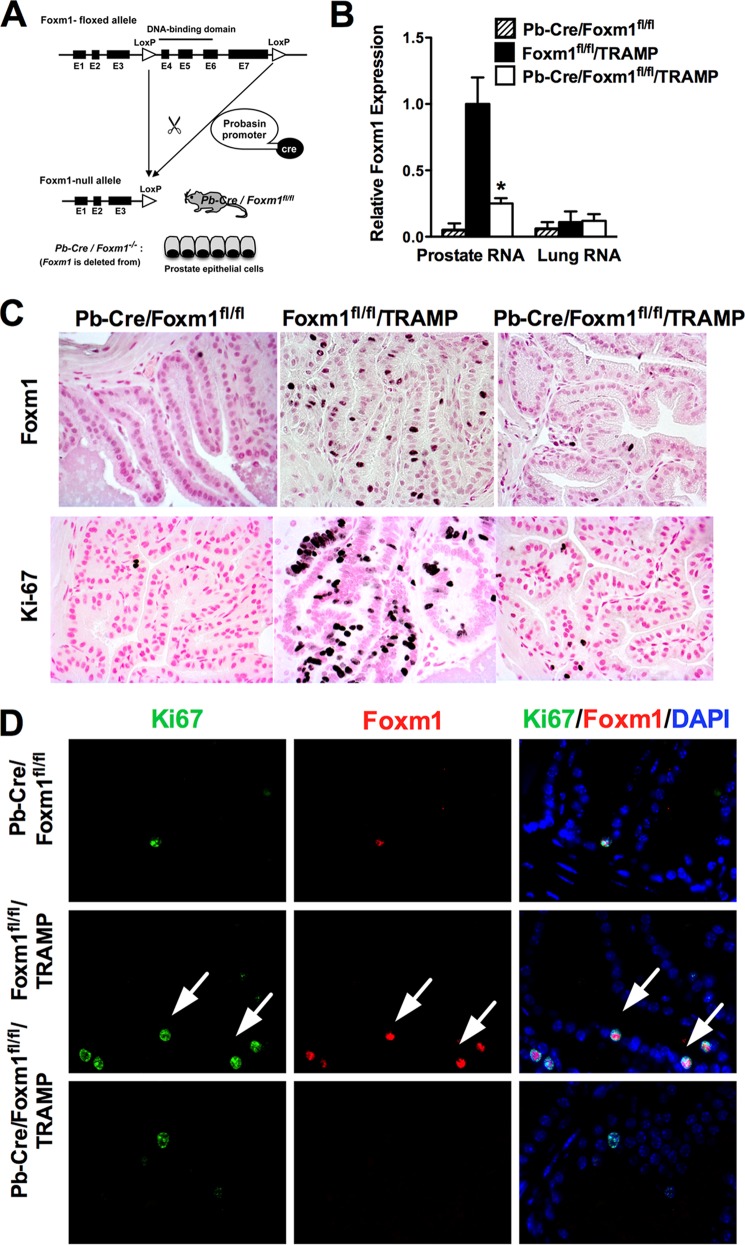

Foxm1fl/fl mice (32) were bred with Pb-Cre transgenic mice (33) to generate Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice. In Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice (Fig. 1A), Cre recombinase is specifically expressed in prostate epithelial cells under control of rat probasin (Pb) promoter. Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice were crossed with TRAMP transgenic mice containing Pb-driven SV40-T large and small antigens (5, 6). Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice were fertile with no obvious abnormalities. Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl, Foxm1fl/fl, and Pb-Cretg/−/TRAMP, TRAMP littermates were used as controls. Mouse prostate glands were harvested 8 and 23 weeks after birth and used for isolation of total prostate mRNA or for immunohistochemistry. Animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation.

FIGURE 1.

Conditional deletion of Foxm1 from prostate epithelial cells. A, schematic drawing of Cre-mediated deletion of the Foxm1-floxed allele in vivo. Expression of Cre-recombinase in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice causes the deletion of exon 4–7 encoding the DNA binding domain and transcriptional activation domain of the Foxm1 protein. B, efficient deletion of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells is shown by qRT-PCR. Total prostate RNA and total lung RNA was prepared from 8-week-old Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl, Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP, and Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent determinations using prostate tissue from n = 4 ± 5 mice per group. C, expression of Foxm1 and Ki-67 in prostate epithelium. Prostate sections from 8-week-old mice were stained with Foxm1 antibody (top panels) or Ki-67 antibodies (bottom panels) and then counterstained with nuclear fast red (red nuclei). Numerous Foxm1-positive and Ki-67-positive cells were observed in prostates of Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. Deletion of Foxm1 in prostates of Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice decreased the number of cells positive for Foxm1 and KI-67. Magnification is ×200. D, co-localization studies identified cells (white arrows) positive for both Ki-67 (green) and Foxm1 (red) in Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates. Deletion of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells decreased the number of Ki-67+ and Foxm1+ cells in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates. Magnification is ×200.

Gain-of-Function of Foxm1 in Prostate Epithelium

Transgenic mice with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible Foxm1 expression (TetO-GFP-Foxm1-ΔN) were previously generated (34). The TetO-GFP-FoxM1-ΔN mice were bred with Pb-Cretg/+/LoxP-stop-LoxP-rtTA(Rosa26)tg/tg mice, the latter of which contained a reverse tetracycline activator (rtTA) knocked into Rosa26 locus (35). In Pb-Cretg/+/LoxP-stop-LoxP-rtTA(Rosa26)tg/+/TetO-GFP-FoxM1-ΔNtg/+ mice (abbreviated as Pb-Foxm1-ΔN), Dox treatment results in prostate epithelial-specific expression of the FoxM1-ΔN transgene due to excision of LoxP-stop-LoxP cassette by the Cre recombinase. To induce Foxm1-ΔN expression, mice were given Dox in food chow beginning at 4 weeks of age and kept on Dox until the end of the experiment. Dox-treated TetO-Foxm1-ΔN littermates lacking the Pb-Cre transgene were used as control for Pb-Foxm1-ΔN transgenic mice. Further controls included Pb-Cretg/−/TetO-Foxm1-ΔNtg/− or Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice without Dox treatment.

Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice were bred with p19ARF−/− mice to generate Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− and Pb- Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF−/− mice. To induce Foxm1 transgene, mice were given Dox at 6 weeks of age. Homozygous Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF−/− mice developed aggressive lymphomas without Dox treatment (data not shown) and were not used to study prostate carcinogenesis. Heterozygous Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+]/− mice were treated with Dox for 23 weeks and harvested along with control Pb-Foxm1-ΔN and p19ARF+/− mice. The orthotopic model of prostate cancer, which uses Myc-CaP tumor cells, was previously described (36).

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from prostates, and analyzed by qRT-PCR using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were amplified with TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) combined with inventoried TaqMan mouse gene expression assays: Foxm1, Mm00514924_m1; β-Actin, Mm00607939_g1; Cdc25b, Mm00499136_m1; Cyclin B1, Mm00838401_g1; Plk1, Mm00440924_g1; Vegf-a, Mm00437304_m1; Foxf1, Mm00487497_m1; Hif1a, Mm00468869_m1; Spdef, Mm01306245_m1; Igf-1, Mm00439560_m1; Fzd1, Mm00445405_s1; CxcR4, Mm01996749_s1; AR, Mm00442688_m1; CxcL12, Mm00442688_m1; p19ARF, Mm00494449_m1. Human (transgenic) Foxm1-ΔN was amplified using Hs00153543_m1 primers. Reactions were analyzed in triplicates and expression levels were normalized to β-Actin.

Cells were transfected using following Foxm1-specific siRNAs: siRNA #1, 5′-GGA CCA CUU CCC UUA CUU U-3′; siRNA #2, 5′-UAA UUA UGU CAA GAU GAUA-3′; siRNA #3, 5′-CCA UUA GGA AGA AGA AAU-3′ (Dharmacon Research, Lafayette, CO). Cells were also transduced with shFoxm1 lentivirus (clone ID: V3LMM_457621, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg PA).

ChIP Assay

TRAMP C2 mouse prostate adenocarcinoma cells were transfected with either CMV-Foxm1 or CMV-empty plasmids using the Neon transfection system following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). 24 h after transfection, cells were cross-linked by addition of formaldehyde, sonicated, and used for immunoprecipitation with a Foxm1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (C-20, Santa Cruz, CA) as described previously (37). DNA fragments were between 500 and 1000 bp in size. Reversed cross-linked ChIP DNA samples were subjected to qPCR using oligonucleotides specific to promoter regions of mouse 11β-Hsd2: −706/−873 (5′-GAG ATG GAA AGG TCA ATG AAG GC-3′and 5′-CAT ACA CAC AGG GAG GGA AAT GC-3′) and −2366/−2480 (5′-GGA AAA GCA AGA AAG TGG AGC G-3′ and 5′-GGA GCC GAG ACA AAG GAT TCA G-3′). Binding of Foxm1 was normalized to DNA of the samples immunoprecipitated with isotype control serum.

Cloning of the Mouse 11β-Hsd2 Promoter Region and Luciferase Assay

We used PCR of mouse genomic DNA to amplify the −2757 to −57 bp region of mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter (GenBank number NC_000074.6) using the following primers: 5′-ctg agg tac ctg gtg cta gtg agt tac tgg tca c-3′ and 5′-GAC TCG AGG CTA GGA CAC GGA ATG-3′. To create the deletion mutants of the −2757 bp 11β-Hsd2 promoter region we used the following primers: −2267 bp, 5′-ctg agg tac cgg tct cct gac tta gaa aat ggg g-3′ and 5′-GAC TCG AGG CTA GGA CAC GGA ATG-3′; −1263 bp, 5′-ctg agg tac cgc tgt gat aag gaa tct atg acc c-3′ and 5′-GAC TCG AGG CTA GGA CAC GGA ATG-3′; −649 bp, 5′-ctg agg tac cta cca ggg acc taa ggc cat gcct-3′ and 5′-GAC TCG AGG CTA GGA CAC GGA ATG-3′. To mutate the potential Foxm1 binding site in the −879 to −892 bp region (5′-aca cac aaacaag-3′) of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter we utilized the GeneArt Site-directed Mutagenesis System (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) to completely eliminate the site without affecting neighboring sequences. The following primers were used: 5′-TGG CGC AGG GTG CCA GGC CAG GAC CTT CAT ACA CAC AGG GA-3′and 5′-TCC CTG TGT GTA TGA AGG TCC TGG CCT GGC ACC CTG CGC CA-3′. The PCR products was cloned into a pGL2-Basic firefly luciferase (LUC) reporter plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI) and verified by DNA sequencing. TRAMP C2 cells were transfected with CMV-Foxm1b or CMV-empty plasmids, as well as with LUC reporter driven by the −2.7-kb 11β-Hsd2 promoter region (11β-Hsd2-LUC) or the deletion mutants. CMV-Renilla was used as an internal control to normalize transfection efficiency. A dual luciferase assay (Promega) was performed 24 h after transfection as described previously (38).

Statistical Analysis

We used Microsoft Excel to calculate S.D. and statistically significant differences between samples using the Student's t test. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Conditional Deletion of Foxm1 from Prostate Epithelial Cells

To investigate the role of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells during PCa formation, we generated transgenic mice containing LoxP-flanked exons 4–7 of the Foxm1 gene (Foxm1fl/fl) and the Probasin-Cre transgene (Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice). In Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice (Fig. 1A), Cre recombinase is specifically expressed in prostate epithelial cells under control of rat probasin (PB) promoter (33). To induce prostate carcinogenesis, Pb-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice were crossed with TRAMP mice containing PB-driven SV40-Tag transgene (22, 24). Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice were fertile with no obvious abnormalities. To determine the efficiency of Foxm1 deletion, total prostate RNA from 8-week-old Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP male mice was examined by qRT-PCR. Compared with control Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP tissues, a 90% decrease in Foxm1 mRNA was only observed in prostate tissue, but not in lung tissues from Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that the deletion of Foxm1 was prostate-specific. The number of Foxm1-positive epithelial cells in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates was greatly reduced, confirming the efficient Foxm1 deletion by the Cre recombinase (Fig. 1C, upper panel). Moreover, the total number of Ki-67 positive cells and the number of Ki-67/Foxm1 double-positive epithelial cell were significantly decreased in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates (Fig. 1D, bottom panel), consistent with a down-regulation in cell proliferation. There were no differences in the number of apoptotic cells in Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP and Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates (data not shown).

Foxm1 Deficiency in Prostate Epithelial Cells Prevents Adenocarcinoma Formation Caused by SV40 T-antigen

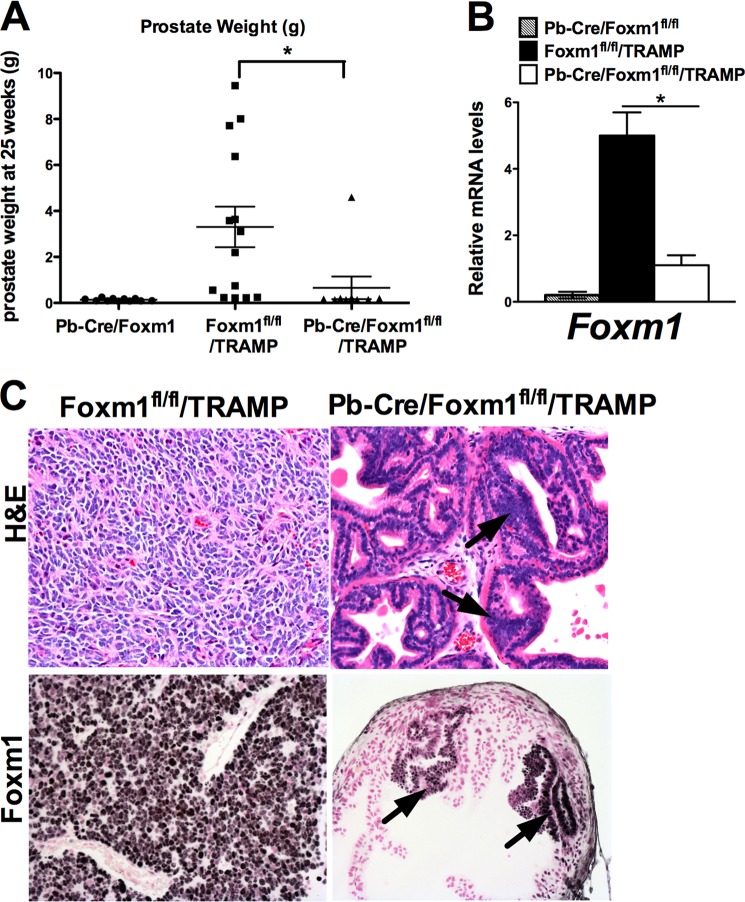

To determine whether Foxm1 expression in prostate epithelial cells was critical for prostate carcinogenesis, Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP and Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mouse prostates were analyzed at 23 weeks of age. The weights of the prostate glands from control Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP and TRAMP groups of mice were 2.3 ± 1.2 and 2.7 ± 2.3 g, respectively (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a significant 20-fold decrease in prostate weight was observed in Foxm1-deficient Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice (prostate weight 0.12 ± 0.03 g, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). The mRNA levels of Foxm1 were decreased in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates, a finding consistent with efficient Foxm1 deletion (Fig. 2B). Histopathological analysis of the H&E-stained sections demonstrated that only 8% (1 of 12) of Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice developed adenocarcinomas compared with 90% (9 of 10) of TRAMP mice and 80% (8 of 10) of Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice (Table 1 and Fig. 2C, upper panel). All tumor lesions, including those that developed in Foxm1-deficient Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates, stained positively for the Foxm1 protein, indicating that tumors developed from non-recombined epithelial cells (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). Furthermore, deletion of Foxm1 prevented the development of mouse PIN at early stages of prostate carcinogenesis (8 weeks, Table 1). Altogether, these results indicate that Foxm1 expression in prostate epithelial cells is required for prostate carcinogenesis in vivo and that depletion of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells is sufficient to inhibit development of PCa in the TRAMP mouse model.

FIGURE 2.

Deletion of Foxm1 from prostate epithelial cells prevents prostate carcinogenesis. A, experimental Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP and control Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice were sacrificed at 23 weeks of age. Prostate glands were collected and weighed. Deletion of Foxm1 significantly decreased (p < 0.05) the weight of prostate glands at 23 weeks of age (top panel). Mean weights of prostate glands (±S.D.) were calculated from 10 to 12 mouse prostates per group. A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*). B, efficiency of Foxm1 deletion in prostate epithelial cells is shown by qRT-PCR. Total prostate RNA was prepared from Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl, Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP, and Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent determinations using prostate tissue from n = 5–10 mice in each group. C, H&E staining shows prostate adenocarcinoma in Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice (left panel) and PINs in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostate (right panel, black arrows).

TABLE 1.

Tumor grade in control and Foxm1 deleted mice

| Mice | 8 Weeks of age |

23 Weeks of age |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice with PIN | Number of mice with PIN out of total number | Mice with prostate carcinoma | Number of mice with prostate carcinoma out of total number | |

| Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP | 0% | 0/7 | 0% | 1/12 |

| TRAMP | 100% | 9/9 | 90% | 9/10 |

| Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP | 100% | 8/8 | 80% | 8/10 |

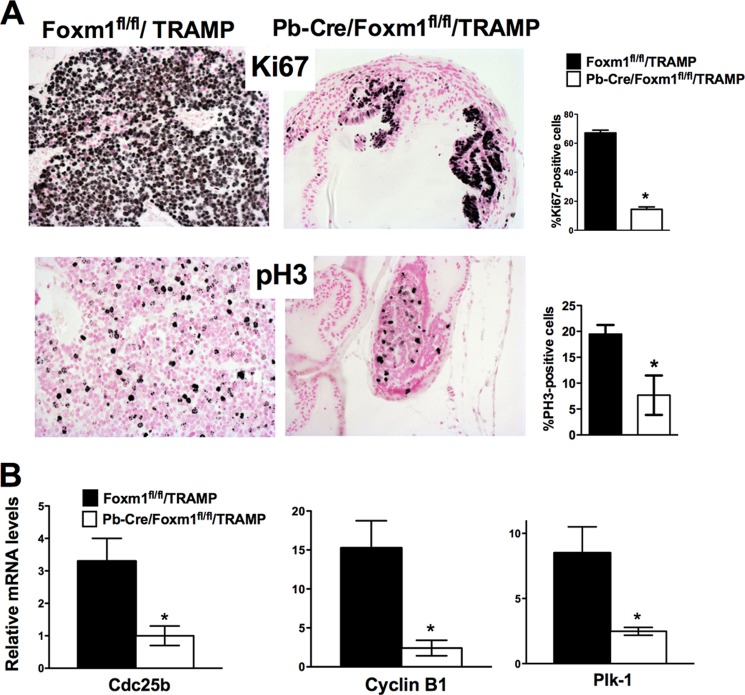

Deletion of Foxm1 Down-regulated Cell Proliferation and Decreased Expression of Cell-cycle Regulatory Genes

Immunohistochemical analysis determined that Ki-67 and pH 3 expression was decreased in 23-week-old Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostate tissue sections, confirming that deletion of Foxm1 expression decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis determined that the numbers of Ki-67-positive and pH 3-positive cells were significantly decreased in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostate sections as compared with control Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP tissue (Fig. 3A). Foxm1 deficiency in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates was associated with decreased mRNA levels of Cdc25b, Cyclin B1, and Plk-1 (Fig. 3B), all known transcriptional targets of Foxm1 (40). Because Cdc25b, Cyclin B1, and Plk-1 are critical for proliferation of tumor cells, their decreased expression can contribute to decreased proliferation and reduced carcinogenesis in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice.

FIGURE 3.

Deletion of Foxm1 decreased cell proliferation and reduced expression of cell-cycle regulatory genes. A, decreased proliferation of tumor cells was observed in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates as demonstrated by reduced numbers of Ki-67-positive and PH3-positive tumor cells. Mouse prostate glands were harvested 23 weeks after birth and used for immunohistochemistry with Ki-67 and PH3 antibodies. Magnification is ×100. Counting of Ki-67-positive and PH3-positive cells were performed using 5 random fields in each of 6 individual mice per group and scored blindly. Data represent mean ± S.D. A p value < 0.01 is shown with asterisks (*). B, decreased mRNA levels of Cdc25b, Cyclin B1, and Plk-1 in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates was found by qRT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent determinations using prostate tissue from n = 5–10 mice in each group. A p value <0.05 is shown with an asterisk.

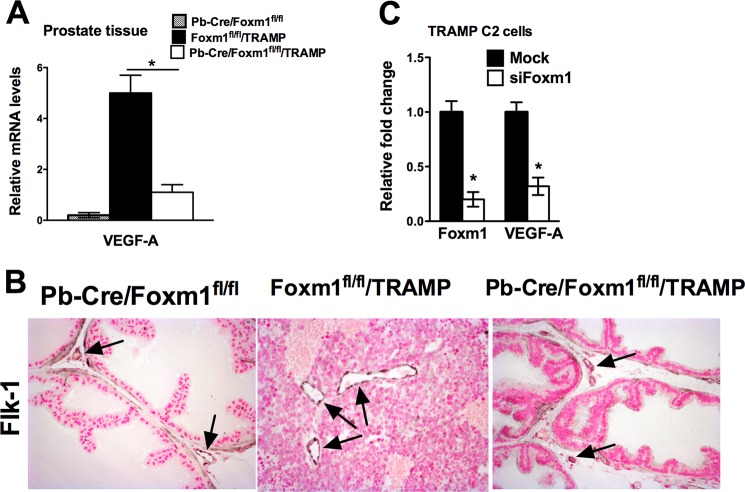

VEGF Expression and Angiogenesis Are Compromised in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP Prostates

Because angiogenesis plays an essential role in prostate cancer progression and VEGF-A is a main angiogenic factor produced by tumor cells (41), we compared the levels of VEGF-A in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP and control prostates. At 23 weeks, VEGF-A mRNA was decreased significantly (p < 0.01) in prostate tissues of Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice as shown by real time qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A). The tumors in control TRAMP mice were well vascularized as demonstrated by immunostaining for endothelial-specific protein Flk-1 (Fig. 4B, middle). In contrast, aberrant angiogenesis did not occur in Foxm1-defecient prostates (Fig. 4B, right). siRNA-mediated depletion of Foxm1 caused a significant reduction in Vegf-a mRNA in cultured TRAMP C2 mouse prostate adenocarcinoma cells in vitro (Fig. 4C), a finding consistent with regulation of Vegf-a by Foxm1 in pancreatic tumor cells (42). Thus, reduced Vegf-a levels may inhibit prostate carcinogenesis in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice.

FIGURE 4.

Reduced angiogenesis and decreased VEGF expression in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. A, mouse prostate glands were harvested 23 weeks after birth and used to isolate total prostate RNA. Decreased Vegf-a mRNA in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates was shown by qRT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. A p value <0.05 is shown with an asterisk (*). B, expression of Flk-1 (Vegf receptor type II) protein was decreased in prostates of Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice compared with TRAMP mice. Prostates sections from 23-week-old mice were stained with Flk-1 antibody (dark brown nuclei) and then counterstained with nuclear fast red (red nuclei). Flk-1-positive cells and vessels were observed inside prostate adenocarcinomas in Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. In the control Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl mice and in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP knock-out mice Flk-1 antibody-stained blood vessels outside of normal prostate epithelium. Black arrows are showing vessels. Magnification is ×100. C, knockdown of Foxm1 by siRNA decreased Vegf-a expression in vitro. Foxm1 depletion in TRAMP C2 prostate adenocarcinoma cells reduced Vegf-a mRNA. TRAMP C2 cells were transfected with siRNA specific for Foxm1 (Foxm1 siRNA) or control siRNA. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. A p value < 0.05 is shown with an asterisk (*).

Foxm1 Deficiency in Prostate Epithelial Cells Alters Expression of Genes Critical for Prostate Carcinogenesis

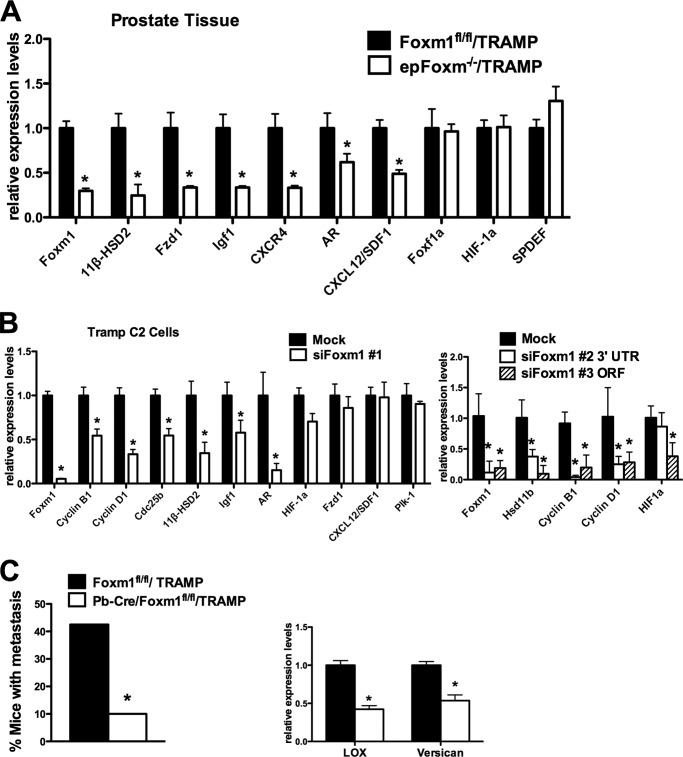

To identify additional Foxm1-regulated target genes, we examined the expression of several genes critical for prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Total RNA was isolated from excised prostate glands and used for real time RT-PCR analysis. In Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates, mRNAs encoding the 11β-Hsd2, Fzd1, Igf1, AR, Cxcl12, and Cxcr3 genes known to mediate carcinogenesis (43–45) were all decreased, whereas Hif-1a, Spdef, and Foxf1 mRNA levels did not change (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the in vivo data (Fig. 1B), knockdown of Foxm1 in cultured TRAMP C2 tumor cells decreased mRNA levels of the cell-cycle regulatory genes Cyclin B1, Cyclin D1, Cdc25b, and Plk-1 in addition to 11β-Hsd2, Igf1, AR, and Hif-1α mediators of prostate carcinogenesis (Fig. 5B). Because all these genes are critical for proliferation of prostate tumor cells and formation of prostate cancer, reduced expression of these genes may contribute to reduced prostate carcinogenesis in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. Moreover, depletion of Foxm1 was associated with decreased mRNA expression of Lox and Versican (Fig. 5C), genes critical for tumor metastasis (46, 47). Consistent with these results, the percentage of Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice with metastasis to the lymph nodes and the lung was dramatically decreased compared with control Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice. Taken together, Foxm1 not only regulates expression of genes critical for PCa cell proliferation and TRAMP tumor formation, but also those that promote tumor progression and metastatic disease.

FIGURE 5.

Deletion of Foxm1 alters expression of genes critical for prostate carcinogenesis. A, qRT-PCR was performed using total prostate RNA isolated from prostate glands of 23-week-old mice. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. B, TRAMP C2 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (Mock) or siRNAs specific for Foxm1 mRNA (siFoxm1). We used three distinct siFoxm1s (siFoxm1 #1, #2, and #3, see ”Experimental Procedures“). Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, total RNA was extracted and analyzed by qRT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. C, deletion of Foxm1 from prostate epithelium in TRAMP mice decreased prostate cancer metastasis. D, decreased mRNAs of Lox and Versican in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates were found by qRT-PCR. A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*).

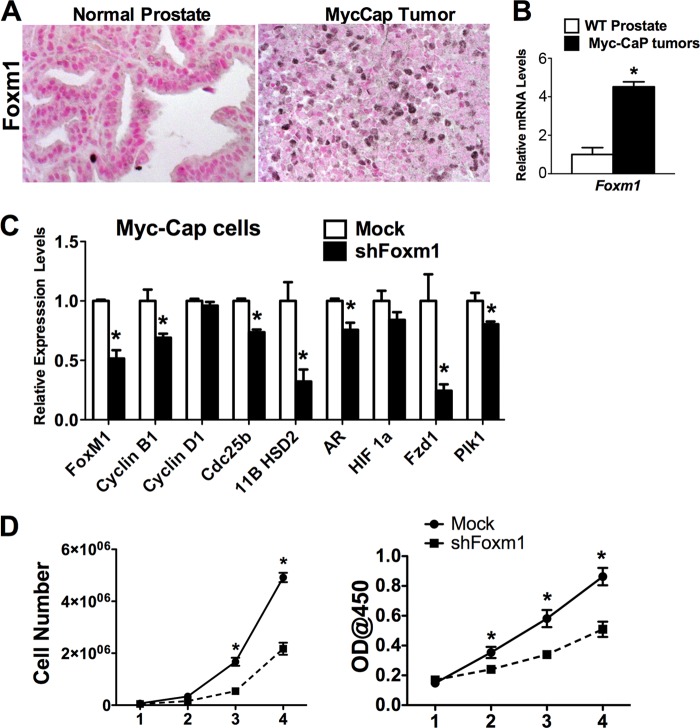

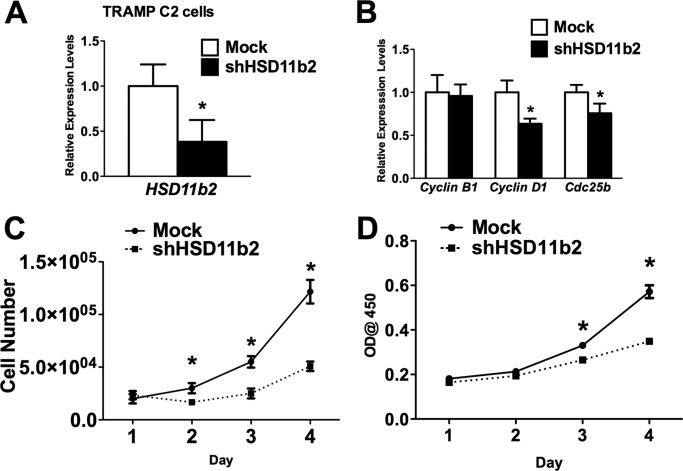

To demonstrate that the role of Foxm1 is not limited to the TRAMP model of prostate cancer, we used Myc-CaP prostate adenocarcinoma cells for the orthotopic injection into mouse prostates. Foxm1 mRNA and protein were increased in Myc-CaP prostate tumors compared with normal prostates (Fig. 6, A and B). Depletion of Foxm1 in Myc-CaP cells by shRNA reduced expression of cell cycle regulatory genes (Fig. 6C) and decreased proliferation of Myc-CaP cells in vitro (Fig. 6D). Thus, Foxm1 induces cell proliferation in both SV40 T-antigen (TRAMP) and c-Myc-transformed tumor cells.

FIGURE 6.

Foxm1 is up-regulated in c-Myc-driven prostate cancer and is required for proliferation of Myc-CaP prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Mouse prostates were harvested 5 weeks after inoculation of Myc-CaP cells and embedded into paraffin blocks or used to isolate RNA. A, Myc-CaP tumors express high levels of Foxm1 protein. Only single Foxm1-positive cell are found in the normal prostates. Prostate tissue sections were stained with antibodies specific for Foxm1. Nuclear fast red was used for counterstaining. Magnification is ×400. B, Foxm1 mRNA is up-regulated in the Myc-CaP tumors. Total RNAs were isolated from prostate glands 5 weeks after inoculation of Myc-CaP cells and examined shown by qRT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. C, depletion of Foxm1 in Myc-CaP cells decreased mRNA levels of proliferation-specific genes. Myc-CaP cells were transduced with either control or shFoxm1 lentiviruses. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. D, depletion of Foxm1 decreased proliferation of Myc-CaP cells in vitro. Control and Foxm1-depleted Myc-CaP cells were seeded in triplicates and counted at different time points using either hemocytometer (left panel) or WST1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (right panel). A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*).

Overexpression of Foxm1 Is Not Sufficient to Induce PCa

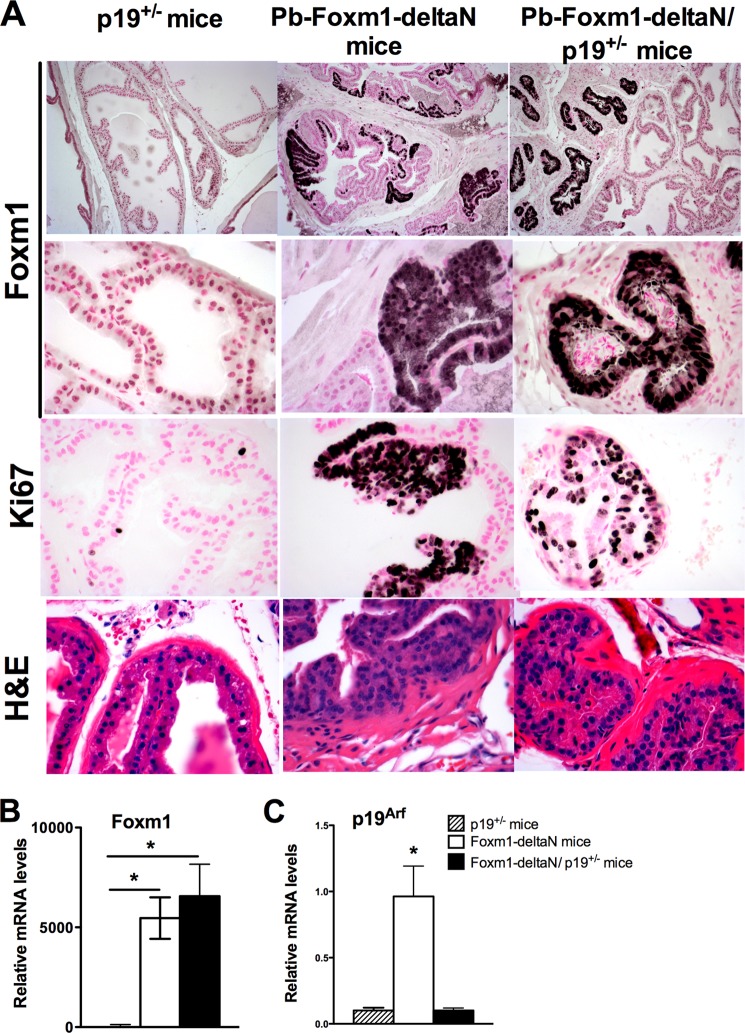

Next, we examined whether overexpression of activated Foxm1 mutant protein (Foxm1-ΔN) either alone or in combination with inactivation of tumor suppressor p19ARF, a known Foxm1 inhibitor (14, 48), would be sufficient to induce prostate carcinogenesis. To induce Foxm1-ΔN expression specifically in prostate epithelial cells, TetO-GFP-FoxM1-ΔN transgenic mice (49) were cross-bred with Pb-Cretg/+/LoxP-stop-LoxP-rtTA(Rosa26)tg/tg mice containing a reverse tetracycline activator (rtTA) knocked into Rosa26 locus. Dox treatment of Pb-Cretg/+/LoxP-stop-LoxP-rtTA(Rosa26)tg/tg mice resulted in prostate epithelial-specific expression of rtTA due to excision of LoxP-stop-LoxP cassette by the Cre recombinase. This strategy resulted in the F1 generation of Pb-Cretg/+/LoxP-stop-LoxP-rtTA(Rosa26)tg/+/TetO-GFP-FoxM1-ΔNtg/+ transgenic mice, subsequently referred to as Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice. Expression of the Pb-Foxm1-ΔN transgene was under Dox control thereby enabling us to study the role of Foxm1 in adult prostate epithelium.

In a second model to study Pb-Foxm1-ΔN overexpression in the presence of p19ARF inactivation, Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice were cross-bred with p19ARF−/− mice. To induce Foxm1 transgene, mice were given Dox at 6 weeks of age. Because homozygous p19ARF−/− expression in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF−/− mice promoted development of aggressive lymphomas independent from Foxm1 transgene activity (data not shown), these mice could not be used in our study. Therefore, we used heterozygous Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− mice along with appropriate controls (Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice and p19ARF+/− mice). Prostates were collected following 16, 24, and 40 weeks of Dox treatment. Although p19ARF+/− prostates exhibited a normal phenotype (Fig. 7A, left panels), overexpression of the Foxm1-ΔN mutant induced prostate epithelial hyperplasia in regions showing strong immunostaining for the Foxm1-ΔN transgenic protein at 24 weeks of Dox treatment (Fig. 7A, middle panels). Foxm1 overexpression on a p19ARF+/− genetic background did not promote PCa development, but caused atrophy of prostate epithelial tubules as evidenced by smaller size of prostate tubules embedded into fibrotic tissue (Fig. 7A, right panels). Altogether, our data demonstrated that overexpression of activated Foxm1-ΔN in adult prostates induced epithelial hyperplasia, but was insufficient to stimulate progression of epithelial hyperplasia to prostate adenocarcinoma. In contrast to hepatocellular carcinomas (50), simultaneous overexpression of Foxm1 and inhibition of the p19ARF tumor suppressor did not induce prostate carcinogenesis in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

Overexpression of Foxm1 is not sufficient to induce prostate tumorigenesis. A, mouse prostates from p19ARF+/−, Pb-Foxm1-ΔN, and Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− mice were harvested at 24 weeks after Dox treatment and embedded into paraffin blocks. Prostate sections were used for H&E staining or immunohistochemistry with antibodies recognizing the Foxm1-ΔN transgene or Ki-67 antibodies. Nuclear fast red was used for counterstaining. PIN was found in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN prostates (middle panels). Atrophy of epithelial tubules was seen in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− prostates (right panels). Prostates in p19ARF+/− mice were normal (left panels). Magnification is ×200 (upper panels) and ×400. B, efficient expression of Foxm1-ΔN transgene in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN and Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− prostates is shown by qRT-PCR for transgenic mRNA. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. C, decreased mRNA levels of p19ARF in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− prostates are shown by qRT-PCR. Total RNAs were isolated from prostate glands of 24-week-old mice were used. A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*).

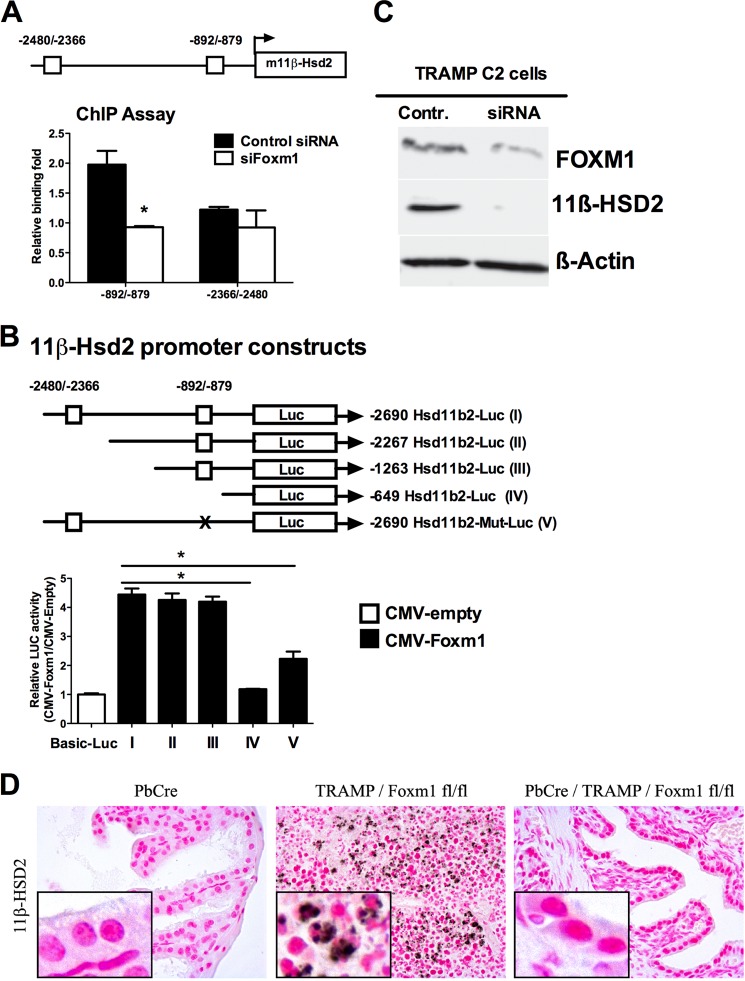

Foxm1 Directly Regulates Hsd11b2 Gene Transcription

Foxm1 induced 11β-Hsd2 mRNA and protein in mouse prostates in vivo and in cultured TRAMP C2 cells as shown by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5, A and B). Consistent with these observations, 11β-Hsd2 protein levels were reduced in Foxm1-defecient TRAMP C2 cells (Fig. 8C) and Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates (Fig. 8D). We next investigated whether 11β-Hsd2 was a direct transcriptional target of Foxm1 in prostate tumor cells. Two potential Foxm1 binding sites were identified within the −2.69-kb promoter region of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 gene (Fig. 8A). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed to demonstrate that the Foxm1 protein physically bound to the −706/−873 bp 11β-Hsd2 promoter region, whereas no specific binding of Foxm1 to the −2366/−2480 bp region was observed (Fig. 8A). To identify functional Foxm1-binding sites in the 11β-Hsd2 promoter region, we performed luciferase reporter assays using the constructs as outlined in Fig. 7B. CMV-Foxm1b significantly increased transcriptional activity of the −2.69 kb 11β-Hsd2 promoter region (Fig. 8B). Analysis of deletion mutants revealed that the −1263/−649-bp region of the 11β-Hsd2 promoter was required for full transcriptional activation of 11β-Hsd2 by Foxm1 (Fig. 8B). Site-directed mutagenesis of Foxm1-binding sequences in the −892/−879 region decreased transcriptional activity of the 11β-Hsd2 promoter, indicating that the −892/−879 region is important for transcriptional regulation of the 11β-Hsd2 gene by Foxm1 (Fig. 8B). Thus, Foxm1 directly bound to and induced transcriptional activity of the 11β-Hsd2 promoter, indicating that 11β-Hsd2 is a direct Foxm1 target.

FIGURE 8.

11β-Hsd2 is a direct transcriptional target of Foxm1. A, a schematic drawings of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter region (m11β-Hsd2). Location of two potential Foxm1 DNA binding sites are indicated (boxes). The ChIP assay demonstrated that Foxm1 protein directly binds to the −706/−873-bp 11β-Hsd2 promoter region, but not to the −2366/−2480-bp region. Cross-linked chromatin from mock-transfected TRAMP C2 mouse prostate adenocarcinoma cells or TRAMP C2 cells transfected with Foxm1-specific siRNA was immunoprecipitated (IP) with either Foxm1 antibodies or IgG control. Genomic DNA in the IP fraction was analyzed for the amount of 11β-Hsd2 promoter DNA using qPCR. Foxm1 binding to genomic DNA was normalized to IgG control. Diminished binding of Foxm1 to the −892/−879-bp 11β-Hsd2 promoter region was observed after siFoxm1 transfection. B, Foxm1 induces transcriptional activity of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter. Schematically shown the luciferase (LUC) reporter constructs that include either the −2.69-kb mouse 11β-Hsd2 promoter region (I, includes both Foxm1 binding sites) or one of its deletion mutants (II–IV). TRAMP C2 cells were transfected with CMV-Foxm1b expression vector and one of the 11β-Hsd2 LUC reporter plasmids. CMV-empty plasmid was used as a control. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection. Dual LUC assays were used to determine LUC activity. Deletion of both Foxm1 binding sites (construct IV) prevented activation of the 11β-Hsd2 promoter region by the CMV-Foxm1b plasmid. Site-directed mutagenesis of Foxm1-binding sequences in the −892/−879 region (construct V) decreased transcriptional activity of the 11β-Hsd2 promoter. Transcriptional induction is shown as a fold-change relative to CMV-empty vector (±S.D.). A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*). C, Foxm1 knockdown by siRNA decreased 11β-Hsd2 protein levels. TRAMP C2 cells were transfected either with control siRNA (Mock) or with siRNA specific for Foxm1 (siFoxm1). Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot. D, decreased 11β-Hsd2 protein expression was observed in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP prostates by immunohistochemistry. Prostate tissue sections of 24-week-old mice were stained with antibodies specific to 11β-Hsd2. Magnification is ×200.

Finally, to determine whether 11β-Hsd2 is important for cellular proliferation in Foxm1-expressing cells, TRAMP C2 tumor cells were transduced with sh11β-Hsd2 lentivirus. Depletion of 11β-Hsd2 was sufficient to decrease cellular proliferation as demonstrated by the reduced number of TRAMP C2 cells in two separate proliferation assays (Fig. 9, A–D). Depletion of 11β-Hsd2 decreased mRNA levels of cell cycle regulatory genes, such as Cyclin D1 and Cdc25b (Fig. 9B), supporting our conclusion that 11β-Hsd2 is important for cellular proliferation in prostate cancer cells.

FIGURE 9.

Depletion of 11β-Hsd2 decreased proliferation of prostate adenocarcinoma cells. TRAMP C2 cells were transduced with sh11β-Hsd2 lentivirus. A, decreased 11β-Hsd2 mRNA was found in sh11β-Hsd2 transduced cells by qRT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization. B, depletion of 11β-Hsd2 decreased Cyclin D1 and Cdc25b mRNAs. C, depletion of 11β-Hsd2 decreased cellular proliferation. Control and 11β-Hsd2-depleted TRAMP C2 cells were seeded in triplicates and counted at different time points using hemocytometer. D, decreased proliferation of 11β-Hsd2-depleted cells is shown by WST1 cell proliferation assay. Control and 11β-Hsd2-depleted TRAMP C2 cells were seeded in triplicates and processed at different time points. A p value < 0.05 is shown with an asterisk (*).

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies demonstrated that aberrant overexpression of Foxm1 in all cell types using ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter accelerated prostate carcinogenesis in TRAMP and LADY transgenic mice (31). Prostate cancer lesions contain a heterogeneous population of cells, which includes epithelial, inflammatory (macrophages, granulocytes), and stromal cells, all of each up-regulate Foxm1 expression during cancer formation (51). Recent studies highlighted the important role of Foxm1 in regulation of cancer-associated inflammation and production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (28), suggesting that Foxm1 may indirectly influence prostate carcinogenesis in Rosa26-Foxm1 mice by inducing tumor-associated inflammation. A specific role of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells, the precursors of prostate adenocarcinoma cells, remain unknown. The important contribution of the current study is the establishment that the expression of Foxm1 in prostate epithelial cells is required for prostate carcinogenesis. Using a novel conditional knock-out mouse line in which Foxm1 was selectively deleted from prostate epithelial cells (Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice), we demonstrated that deletion of Foxm1 prevented prostate carcinogenesis in TRAMP mice. The Foxm1 deletion in Pb-Cre Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice occurs at the same time as the initiation of prostate cancer through the Pb-driven SV40 T-antigen (TRAMP model). Therefore, it is possible that Foxm1 is important for both cancer initiation and cancer progression. Because the aberrant expression of Foxm1 is found in human prostate adenocarcinomas and its expression correlates with the severity of the disease (29), our findings provide foundation for the development of new therapeutic approaches based on inhibition of Foxm1.

Glucocorticoids (GC) are widely used in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs to treat prostate cancer (52, 53). GC inhibit multiple steps in prostaglandin cascade, including enzymatic activity of cytosolic phospholipase A2, which releases the Cox substrate arachidonic acid. GC also inhibit the expression of both Cox-2 and microsomal PGE synthase, the terminal enzyme of Cox-2-mediated prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis (54, 55). However, the adverse side effects of immune suppression limit the use of GC in clinic. 11β-Hsd2 is an enzyme involved in metabolism of GC, particularly in the conversion of the active ligand cortisol to the inactive agonist cortisone (44). Cortisol binds to the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor, which then translocate into the nucleus and activates anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory genes. In the presence of agonist cortisone, the glucocorticoid receptor is not activated and is not providing the anti-proliferative/anti-inflammatory response. Increased expression of 11β-Hsd2 was associated with increased tumor cell proliferation due to increased conversion of cortisol to agonist cortisone (56, 57). In the current study, we demonstrated that 11β-Hsd2 mRNA and protein were increased in the prostate tumors of TRAMP mice, implicating 11β-Hsd2 in proliferation of prostate tumor cells in vivo. Conditional deletion of Foxm1 from tumor cells prevented the up-regulation of 11β-Hsd2, coinciding with decreased carcinogenesis and reduced proliferation of prostate tumor cells. 11β-Hsd2 is a direct transcriptional target of Foxm1, because Foxm1 directly bound to and increased promoter activity of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 gene through the −706/−873 region. Thus, decreased expression of 11β-Hsd2 in Foxm1-deficient prostates may contribute to decreased tumor cell proliferation and reduced prostate carcinogenesis in Pb-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl/TRAMP mice.

Based on our studies with Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice, it appears that Foxm1 alone is not sufficient to initiate prostate tumorigenesis. The Pb-Foxm1-ΔN mice developed PINs, but the PINs did not progress into prostate adenocarcinomas. These data are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that overexpression of Foxm1 in pulmonary type II cells did not induce the formation of lung tumors (49). One of the explanations of resistance to form tumors in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN prostates is that p19ARF tumor suppressor, a known inhibitor of Foxm1 (14, 48), prevents tumor-promoting properties of Foxm1. In fact, we found that expression of p19ARF was increased in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN prostates. Loss of p19ARF function is a critical event for tumor promotion as evidenced by extinguished expression of the p19ARF protein in a variety of tumors through DNA methylation and silencing of the p19ARF promoter region (2). Expression of the ARF tumor suppressor is induced in response to oncogenic stimuli and prevents abnormal cell proliferation through stabilization of p53 tumor suppressor (59). p19ARF also mediates p53-independent cell cycle arrest through the targeting of FoxM1, E2F1, and c-Myc transcription factors to the nucleolus, thus preventing their transcriptional activation of cell cycle regulatory genes (12, 14, 18, 40, 58). The p19ARF protein inhibited Foxm1 transcriptional activity during development of hepatocellular carcinoma (14).

To overcome inhibition of Foxm1 by the p19ARF tumor suppressor, we created transgenic mice overexpressing Foxm1-ΔN in prostate epithelial cells in p19ARF−/− background. However, those mice succumb to lymphomas earlier than they developed prostate cancer. Genetic inactivation of one p19ARF copy in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− prostates was insufficient to induce prostate carcinogenesis. We also found that overexpression of Foxm1-ΔN alone or in the absence of one copy of tumor suppressor p19ARF induced epithelial hyperplasia, but was insufficient to stimulate progression of epithelial hyperplasia to prostate adenocarcinomas. These data suggest that either a complete inactivation of p19ARF, as was achieved in liver tumors (50), or deregulation of other tumorigenic pathways is necessary to promote oncogenic properties of Foxm1 in prostate epithelium. Consistent with this hypothesis, Foxm1 synergized with K-Ras (49) and β-catenin (39) to induce progression of lung and brain cancer, respectively. Interestingly, Foxm1-overexpressing prostate tubules in Pb-Foxm1-ΔN/p19ARF+/− mice underwent a complete atrophy with obliteration of lumen. These results indicate that Foxm1/p19ARF signaling is critical for normal homeostasis in prostate epithelium.

In summary, Foxm1 expression in prostate epithelial cells is required for prostate carcinogenesis induced by SV40 T antigens. Decreased prostate carcinogenesis in Foxm1-deficient mice was associated with decreased proliferation of tumor cells, diminished angiogenesis, and reduced expression of Cdc25b, Cyclin B1, Plk-1, Vegf-a, Lox, and Versican, all of which are critical for cellular proliferation and tumor metastasis. mRNA and protein levels of 11β-Hsd2, an enzyme playing an important role in tumor cell proliferation, were reduced in Foxm1-deficient PCa tumors in vivo and in Foxm1-deficient prostate cancer cells in vitro. Foxm1 bound to and increased promoter activity of the mouse 11β-Hsd2 gene, indicating that the 11β-Hsd2 is a direct transcriptional target of Foxm1. Our results suggest that inhibition of Foxm1 is a promising therapeutic approach for prostate cancer chemotherapy in human patients.

Acknowledgment

We thank Emily Cross for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA142724 (to T. V. K.) and Department of Defense Award PC080478 (to T. V. K.).

- PIN

- prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- PCa

- prostate carcinoma

- Cre

- Cre recombinase

- Fox

- Forkhead box transcription factor

- 11β-Hsd2

- 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II

- ARF

- alternative reading frame

- TRAMP

- transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate

- Dox

- doxycycline

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- rtTA

- reverse tetracycline activator

- GC

- glucocorticoids.

REFERENCES

- 1. McCormick F. (1999) Signalling networks that cause cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 9, M53–M56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sherr C. J., McCormick F. (2002) The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell 2, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berges R. R., Vukanovic J., Epstein J. I., CarMichel M., Cisek L., Johnson D. E., Veltri R. W., Walsh P. C., Isaacs J. T. (1995) Implication of cell kinetic changes during the progression of human prostatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 1, 473–480 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uzgare A. R., Kaplan P. J., Greenberg N. M. (2003) Differential expression and/or activation of P38MAPK, ERK1/2, and jnk during the initiation and progression of prostate cancer. The Prostate 55, 128–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao H., Ouyang X., Banach-Petrosky W. A., Gerald W. L., Shen M. M., Abate-Shen C. (2006) Combinatorial activities of Akt and B-Raf/Erk signaling in a mouse model of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14477–14482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korver W., Roose J., Clevers H. (1997) The winged-helix transcription factor Trident is expressed in cycling cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1715–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ye H., Kelly T. F., Samadani U., Lim L., Rubio S., Overdier D. G., Roebuck K. A., Costa R. H. (1997) Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/fork head homolog 11 is expressed in proliferating epithelial and mesenchymal cells of embryonic and adult tissues. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 1626–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yao K. M., Sha M., Lu Z., Wong G. G. (1997) Molecular analysis of a novel winged helix protein, WIN. Expression pattern, DNA binding property, and alternative splicing within the DNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19827–19836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao Y. Y., Gao X. P., Zhao Y. D., Mirza M. K., Frey R. S., Kalinichenko V. V., Wang I. C., Costa R. H., Malik A. B. (2006) Endothelial cell-restricted disruption of FoxM1 impairs endothelial repair following LPS-induced vascular injury. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2333–2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Major M. L., Lepe R., Costa R. H. (2004) Forkhead box M1B transcriptional activity requires binding of Cdk-cyclin complexes for phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of p300/CBP coactivators. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 2649–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma R. Y., Tong T. H., Cheung A. M., Tsang A. C., Leung W. Y., Yao K. M. (2005) Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling stimulates the nuclear translocation and transactivating activity of FOXM1c. J. Cell Sci. 118, 795–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costa R. H., Kalinichenko V. V., Major M. L., Raychaudhuri P. (2005) New and unexpected. Forkhead meets ARF. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang X., Kiyokawa H., Dennewitz M. B., Costa R. H. (2002) The Forkhead Box m1b transcription factor is essential for hepatocyte DNA replication and mitosis during mouse liver regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16881–16886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalinichenko V. V., Major M. L., Wang X., Petrovic V., Kuechle J., Yoder H. M., Dennewitz M. B., Shin B., Datta A., Raychaudhuri P., Costa R. H. (2004) Foxm1b transcription factor is essential for development of hepatocellular carcinomas and is negatively regulated by the p19ARF tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 18, 830–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang X., Krupczak-Hollis K., Tan Y., Dennewitz M. B., Adami G. R., Costa R. H. (2002) Increased hepatic Forkhead Box M1B (FoxM1B) levels in old-aged mice stimulated liver regeneration through diminished p27Kip1 protein levels and increased Cdc25B expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44310–44316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weber J. D., Taylor L. J., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J., Bar-Sagi D. (1999) Nucleolar Arf sequesters Mdm2 and activates p53. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamijo T., Zindy F., Roussel M. F., Quelle D. E., Downing J. R., Ashmun R. A., Grosveld G., Sherr C. J. (1997) Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell 91, 649–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martelli F., Hamilton T., Silver D. P., Sharpless N. E., Bardeesy N., Rokas M., DePinho R. A., Livingston D. M., Grossman S. R. (2001) p19ARF targets certain E2F species for degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4455–4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Datta A., Nag A., Raychaudhuri P. (2002) Differential regulation of E2F1, DP1, and the E2F1/DP1 complex by ARF. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 8398–8408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Hao Y., Xu J., Murray T., Thun M. J. (2008) Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J. Clin. 58, 71–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abate-Shen C., Shen M. M. (2002) Mouse models of prostate carcinogenesis. Trends Genet. 18, S1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenberg N. M., DeMayo F., Finegold M. J., Medina D., Tilley W. D., Aspinall J. O., Cunha G. R., Donjacour A. A., Matusik R. J., Rosen J. M. (1995) Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3439–3443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Janssens V., Goris J., Van Hoof C. (2005) PP2A. The expected tumor suppressor. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gingrich J. R., Barrios R. J., Morton R. A., Boyce B. F., DeMayo F. J., Finegold M. J., Angelopoulou R., Rosen J. M., Greenberg N. M. (1996) Metastatic prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Cancer Res. 56, 4096–4102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kasper S. (2005) Survey of genetically engineered mouse models for prostate cancer. Analyzing the molecular basis of prostate cancer development, progression, and metastasis. J. Cell. Biochem. 94, 279–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Myatt S. S., Lam E. W. (2007) The emerging roles of forkhead box (Fox) proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 847–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kalin T. V., Ustiyan V., Kalinichenko V. V. (2011) Multiple faces of FoxM1 transcription factor. Lessons from transgenic mouse models. Cell Cycle 10, 396–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Balli D., Ren X., Chou F. S., Cross E., Zhang Y., Kalinichenko V. V., Kalin T. V. (2012) Foxm1 transcription factor is required for macrophage migration during lung inflammation and tumor formation. Oncogene 31, 3875–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalin T. V., Wang I. C., Ackerson T. J., Major M. L., Detrisac C. J., Kalinichenko V. V., Lyubimov A., Costa R. H. (2006) Increased levels of the FoxM1 transcription factor accelerate development and progression of prostate carcinomas in both TRAMP and LADY transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 66, 1712–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang I. C., Meliton L., Ren X., Zhang Y., Balli D., Snyder J., Whitsett J. A., Kalinichenko V. V., Kalin T. V. (2009) Deletion of Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor from respiratory epithelial cells inhibits pulmonary tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE 4, e6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang I. C., Meliton L., Tretiakova M., Costa R. H., Kalinichenko V. V., Kalin T. V. (2008) Transgenic expression of the forkhead box M1 transcription factor induces formation of lung tumors. Oncogene 27, 4137–4149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krupczak-Hollis K., Wang X., Kalinichenko V. V., Gusarova G. A., Wang I.-C., Dennewitz M. B., Yoder H. M., Kiyokawa H., Kaestner K. H., Costa R. H. (2004) The mouse Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is essential for hepatoblast mitosis and development of intrahepatic bile ducts and vessels during liver morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 276, 74–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maddison L. A., Nahm H., DeMayo F., Greenberg N. M. (2000) Prostate specific expression of Cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis 26, 154–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang I. C., Snyder J., Zhang Y., Lander J., Nakafuku Y., Lin J., Chen G., Kalin T. V., Whitsett J. A., Kalinichenko V. V. (2012) Foxm1 mediates cross talk between Kras/mitogen-activated protein kinase and canonical Wnt pathways during development of respiratory epithelium. Mol. Cell Biol. 32, 3838–3850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Belteki G., Haigh J., Kabacs N., Haigh K., Sison K., Costantini F., Whitsett J., Quaggin S. E., Nagy A. (2005) Conditional and inducible transgene expression in mice through the combinatorial use of Cre-mediated recombination and tetracycline induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Watson P. A., Ellwood-Yen K., King J. C., Wongvipat J., Lebeau M. M., Sawyers C. L. (2005) Context-dependent hormone-refractory progression revealed through characterization of a novel murine prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 65, 11565–11571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Balli D., Zhang Y., Snyder J., Kalinichenko V. V., Kalin T. V. (2011) Endothelial cell-specific deletion of transcription factor FoxM1 increases urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 71, 40–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kalin T. V., Wang I. C., Meliton L., Zhang Y., Wert S. E., Ren X., Snyder J., Bell S. M., Graf L., Jr., Whitsett J. A., Kalinichenko V. V. (2008) Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is required for perinatal lung function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19330–19335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang N., Wei P., Gong A., Chiu W. T., Lee H. T., Colman H., Huang H., Xue J., Liu M., Wang Y., Sawaya R., Xie K., Yung W. K., Medema R. H., He X., Huang S. (2011) FoxM1 promotes β-catenin nuclear localization and controls Wnt target-gene expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 20, 427–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang I. C., Chen Y. J., Hughes D., Petrovic V., Major M. L., Park H. J., Tan Y., Ackerson T., Costa R. H. (2005) Forkhead box M1 regulates the transcriptional network of genes essential for mitotic progression and genes encoding the SCF (Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 10875–10894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harper S. J., Bates D. O. (2008) VEGF-A splicing. The key to anti-antiogenic therapeutics? Nat. Rev. 8, 880–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Z., Banerjee S., Kong D., Li Y., Sarkar F. H. (2007) Down-regulation of Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor leads to the inhibition of invasion and angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 67, 8293–8300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang M. Z., Xu J., Yao B., Yin H., Cai Q., Shrubsole M. J., Chen X., Kon V., Zheng W., Pozzi A., Harris R. C. (2009) Inhibition of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II selectively blocks the tumor COX-2 pathway and suppresses colon carcinogenesis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 876–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rabbitt E. H., Gittoes N. J., Stewart P. M., Hewison M. (2003) 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, cell proliferation and malignancy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 85, 415–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pollak M. (2012) The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia. An update. Nat. Rev. 12, 159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barker H. E., Cox T. R., Erler J. T. (2012) The rationale for targeting the LOX family in cancer. Nat. Rev. 12, 540–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Edwards I. J. (2012) Proteoglycans in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 9, 196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gusarova G. A., Wang I. C., Major M. L., Kalinichenko V. V., Ackerson T., Petrovic V., Costa R. H. (2007) A cell-penetrating ARF peptide inhibitor of FoxM1 in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang I. C., Zhang Y., Snyder J., Sutherland M. J., Burhans M. S., Shannon J. M., Park H. J., Whitsett J. A., Kalinichenko V. V. (2010) Increased expression of FoxM1 transcription factor in respiratory epithelium inhibits lung sacculation and causes Clara cell hyperplasia. Dev. Biol. 347, 301–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Park H. J., Gusarova G., Wang Z., Carr J. R., Li J., Kim K. H., Qiu J., Park Y. D., Williamson P. R., Hay N., Tyner A. L., Lau L. F., Costa R. H., Raychaudhuri P. (2011) Deregulation of FoxM1b leads to tumour metastasis. EMBO Mol. Med. 3, 21–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Visser K. E., Eichten A., Coussens L. M. (2006) Paradoxical role of the immune system during cancer development. Nat. Rev. 6, 24–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kelly W. K., Halabi S., Carducci M., George D., Mahoney J. F., Stadler W. M., Morris M., Kantoff P., Monk J. P., Kaplan E., Vogelzang N. J., Small E. J. (2012) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel and prednisone with or without bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. CALGB 90401. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 1534–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Richards J., Lim A. C., Hay C. W., Taylor A. E., Wingate A., Nowakowska K., Pezaro C., Carreira S., Goodall J., Arlt W., McEwan I. J., de Bono J. S., Attard G. (2012) Interactions of abiraterone, eplerenone, and prednisolone with wild-type and mutant androgen receptor. A rationale for increasing abiraterone exposure or combining with MDV3100. Cancer Res. 72, 2176–2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stichtenoth D. O., Thorén S., Bian H., Peters-Golden M., Jakobsson P. J., Crofford L. J. (2001) Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase is regulated by proinflammatory cytokines and glucocorticoids in primary rheumatoid synovial cells. J. Immunol. 167, 469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang M. Z., Harris R. C., McKanna J. A. (1999) Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in rat renal cortex by adrenal glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 15280–15285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koyama K., Myles K., Smith R., Krozowski Z. (2001) Expression of the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II enzyme in breast tumors and modulation of activity and cell growth in PMC42 cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 76, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hundertmark S., Buhler H., Rudolf M., Weitzel H. K., Ragosch V. (1997) Inhibition of 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity enhances the antiproliferative effect of glucocorticosteroids on MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 breast cancer cells. J. Endocrinol. 155, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Qi Y., Gregory M. A., Li Z., Brousal J. P., West K., Hann S. R. (2004) p19ARF directly and differentially controls the functions of c-Myc independently of p53. Nature 431, 712–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lowe S. W., Sherr C. J. (2003) Tumor suppression by Ink4a-Arf. Progress and puzzles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]