Background: G protein-coupled receptors generating cAMP at nerve terminals modulate neurotransmitter release.

Results: β-Adrenergic receptor enhances glutamate release via Epac protein activation and Munc13-1 translocation at cerebrocortical nerve terminals.

Conclusion: Protein kinase A-independent signaling pathways triggered by β-adrenergic receptors control presynaptic function.

Significance: β-Adrenergic receptors target presynaptic release machinery.

Keywords: Cyclic AMP (cAMP), G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Neurotransmitter Release, Phospholipase C, Synaptosomes, Epac Proteins, Munc13–1, RIM1α, Rab3A

Abstract

The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin facilitates synaptic transmission presynaptically via cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). In addition, cAMP also increases glutamate release via PKA-independent mechanisms, although the downstream presynaptic targets remain largely unknown. Here, we describe the isolation of a PKA-independent component of glutamate release in cerebrocortical nerve terminals after blocking Na+ channels with tetrodotoxin. We found that 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, a specific activator of the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), mimicked and occluded forskolin-induced potentiation of glutamate release. This Epac-mediated increase in glutamate release was dependent on phospholipase C, and it increased the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Moreover, the potentiation of glutamate release by Epac was independent of protein kinase C, although it was attenuated by the diacylglycerol-binding site antagonist calphostin C. Epac activation translocated the active zone protein Munc13-1 from soluble to particulate fractions; it increased the association between Rab3A and RIM1α and redistributed synaptic vesicles closer to the presynaptic membrane. Furthermore, these responses were mimicked by the β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) agonist isoproterenol, consistent with the immunoelectron microscopy and immunocytochemical data demonstrating presynaptic expression of βARs in a subset of glutamatergic synapses in the cerebral cortex. Based on these findings, we conclude that βARs couple to a cAMP/Epac/PLC/Munc13/Rab3/RIM-dependent pathway to enhance glutamate release at cerebrocortical nerve terminals.

Introduction

The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin presynaptically facilitates synaptic transmission and glutamate release at many synapses (1–9). Several studies have found that this presynaptic facilitation is dependent on the activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) (1, 2, 4, 8), consistent with the finding that many proteins of the release machinery are targets of PKA, such as rabphilin-3 (10), synapsins (11), Rab3-interacting molecule (RIM)3 (12–14), and Snapin (15). A PKA-dependent component of release has been identified in studies of evoked synaptic transmission responses (1, 4), because Na+, Ca2+-dependent K+ and Ca2+ channels are also PKA targets (16–21). However, forskolin-induced facilitation of glutamate release also occurs via PKA-independent mechanisms (5), in which the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) is implicated (7, 9). In fact, forskolin-induced increases in the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents are fully dependent on Epac activation (9).

Epac proteins contain multiple domains, including one (Epac1) or two (Epac2) cAMP regulatory domains and a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (22). Both Epac1 and Epac2 are expressed in the brain, in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (23). Despite the role of Epac proteins in regulating transmitter release, how these proteins interact with the release machinery to enhance its activity at central synapses is unknown. In non-neuronal preparations, Epac enhances exocytosis of the acrosome via PLC-dependent Ca2+ mobilization, and it activates small G proteins, including Rap1 and Rab3 (24). Epac2 regulates insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells (25) through the activation of PLCϵ (26), and it binds to the Rab3-interacting molecule protein (RIM) in the active zone (27). By contrast, in expression systems (HEK293 cells), Epac specifically activates PLCϵ by activating Rap2, provoking inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated release of Ca2+ from internal stores (28). However, it remains unknown whether the interactions of Epac with the release machinery proteins found in other secretory systems also occur in central nerve terminals.

The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin has been widely used to presynaptically enhance both synaptic transmission and glutamate release at many synapses. Because all isoforms of adenylyl cyclase are stimulated by the GTP-bound α subunit of Gs (Gαs) (29), and the activation of β-adrenergic receptors (βARs) mimics the potentiating effect of forskolin on PKA-dependent neurotransmitter release (4, 20, 30, 31), we sought to determine whether the PKA-independent effects of Epac are triggered by the stimulation of Gs protein-coupled receptors at central nerve terminals.

We found that in cerebrocortical nerve terminals, the PKA-independent component of the forskolin-induced facilitation of glutamate release can be isolated by blocking Na+ channels with tetrodotoxin. The βAR agonist isoproterenol mimicked this response, consistent with the demonstration of presynaptic βARs in a subset of glutamatergic synapses of the cerebral cortex by immunoelectron microscopy. The PKA-independent response induced by isoproterenol was mimicked and occluded by the Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT. Moreover, both the isoproterenol- and 8-pCPT-mediated responses were PLC-dependent, and they were attenuated by the diacylglycerol-binding site antagonist calphostin C. Furthermore, isoproterenol and 8-pCPT induced the translocation of Munc13-1, an active zone protein essential for synaptic vesicle priming, from soluble to particulate fractions, as well as promoting synaptic vesicle redistribution to positions closer to the presynaptic membrane. Finally, 8-pCPT promoted the association of Rab3 with the active zone protein RIM. Based on our findings, we conclude that the βAR/cAMP/Epac signaling pathway acts on the Rab3 and Munc13-1 proteins of the release machinery, enhancing glutamate release.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Synaptosome Preparations

All animal handling procedures were performed in accordance with European Commission guidelines (2010/63/UE), and they were approved by the Animal Research Committee at Universidad Complutense. Synaptosomes were purified from the cerebral cortex of adult (2–3 months old) C57BL/6 mice on discontinuous Percoll gradients (Amersham Biosciences) as described previously (32). Briefly, the tissue was homogenized in medium containing 0.32 m sucrose (pH 7.4), the homogenate was centrifuged for 2 min at 2,000 × g and 4 °C, and the supernatant was then spun again for 12 min at 9,500 × g. From the pellets obtained, the loosely compacted white layer containing the majority of the synaptosomes was gently resuspended in 0.32 m sucrose (pH 7.4), and an aliquot of this synaptosomal suspension (2 ml) was placed onto a 3-ml Percoll discontinuous gradient containing 0.32 m sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 0.25 mm dl-dithiothreitol, and 3, 10, or 23% Percoll (pH 7.4). After centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the synaptosomes were recovered from between the 10% and the 23% Percoll bands, and they were diluted in a final volume of 30 ml of HEPES-buffered medium (HBM; 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 5 mm NaHCO3, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4)). Following further centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 10 min, the synaptosome pellet was resuspended in 6 ml of HBM, and the protein content was determined by the Biuret method. Finally, 0.75 mg of the synaptosomal suspension was diluted in 2 ml of HBM and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellets containing the synaptosomes were stored on ice. Under these conditions, the synaptosomes remain fully viable for at least 4–6 h, as determined by the extent of KCl-evoked glutamate release.

Glutamate Release

Glutamate release was assayed by on-line fluorimetry as described previously (32). Synaptosomal pellets were resuspended in HBM (0.67 mg/ml) and preincubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the presence of 16 μm bovine serum albumin (BSA) to bind any free fatty acids released from synaptosomes during preincubation (33). Adenosine deaminase (1.25 units/mg; Roche Applied Science) was added for 30 min, and the synaptosomes were then washed by centrifugation for 30 s at 13,000 × g and resuspended in HBM. A 1-ml aliquot of the synaptosomes was transferred to a stirred cuvette containing 1 mm NADP+, 50 units of glutamate dehydrogenase (Sigma), and 1.33 mm CaCl2, and the fluorescence of NADPH was measured in a PerkinElmer Life Sciences LS-50 luminescence spectrometer at excitation and emission wavelengths of 340 and 460 nm, respectively. Data were obtained at 2-s intervals, and fluorescence traces were calibrated by the addition of 2 nmol of glutamate at the end of each assay. In experiments with KCl (5 mm), the Ca2+-dependent release was calculated by subtracting the release obtained during a 5-min depolarization at 200 nm free [Ca2+] from the release at 1.33 mm CaCl2. Control release was Ca2+-dependent release induced by KCl (5 mm) in the absence of any addition. Spontaneous release was measured in the presence of the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (1 μm) at 1.33 mm CaCl2. Control release was the release after 10 min. In release experiments with ionomycin and tetrodotoxin, the sodium channel blocker was added 2 min prior to ionomycin-induced glutamate release, which was calculated by subtracting the release observed during a 10-min period in the absence of ionomycin (basal) from that observed in its presence. The concentration of ionomycin (Calbiochem) was fixed in each experiment (0.5–1.0 μm) in order to achieve 0.5–0.6 nmol of Glu/mg. The following drugs were administered as indicated in the figure legends: the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin (15 μm), the PKA inhibitor H-89 (10 μm), the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channel blocker ZD7288 (60 μm), the GDP-GTP exchange inhibitor brefeldin A (100 μm), the active PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 μm), the inactive PLC inhibitor U73343 (2 μm), the diacylglycerol (DAG)-binding protein inhibitor calphostin C (0.1 μm), the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide (1 μm), and the calmodulin antagonist calmidazolium (1 μm), all obtained from Calbiochem; the Epac activator 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (50 μm), the cAMP analog Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μm), the PKA activator N6-Bnz-cAMP (500 μm), and the phosphodiesterase-resistant 8-pCPT analog Sp-8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μm), obtained from BioLog (Bremen, Germany); the vacuolar ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (1 μm), obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and the βAR agonist isoproterenol (100 μm) and antagonist propranolol (100 μm), obtained from Sigma.

IP1 Accumulation

IP1 accumulation was determined using the IP-One kit (Cisbio, Bioassays, Bagnol sur-Cèze, France) (34). Synaptosomes (0.67 mg/ml) in HBM containing 16 μm BSA and adenosine deaminase (1.25 units/mg protein) were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After 25 min, 50 mm LiCl was added to inhibit inositol monophosphatase. Other drugs were added as indicated in the figure legends. Synaptosomes were collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 4 °C and 13,000 × g, and they were resuspended (1 mg/0.1 ml) in lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, 0.8 m potassium fluoride, 0.2% (w/v) BSA, and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (pH 7.0)). The lysed synaptosomes were transferred to a 96-well assay plate, and the following HTRF components were added diluted in lysis buffer: the europium cryptate-labeled anti-IP1 antibody and the d2-labeled IP1 analog. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, europium cryptate fluorescence and time-resolved FRET signals were measured at 620 and 665 nm, respectively, 50 μs after excitation at 337 nm, on a FluoStar Omega fluorimeter (BMG Labtechnologies, Offenburg, Germany). The fluorescence intensities measured at 620 and 665 nm correspond to the total europium cryptate emission and the FRET signal, respectively. The specific FRET signal was calculated using the following equation: ΔF% = 100 × (Rpos − Rneg)/(Rneg), where Rpos is the fluorescence ratio (665/620 nm) calculated in the wells incubated with both donor- and acceptor-labeled antibodies, and Rneg is the same ratio for the negative control incubated with only the donor fluorophore-labeled antibody. The FRET signal (ΔF%), which is inversely proportional to the concentration of IP1 in the cells, was then transformed to the accumulated IP1 value using a calibration curve prepared using the same plate.

cAMP Accumulation

AMP accumulation was determined using a cAMP dynamic 2 kit (Cisbio). The assay was similar to that described for IP1 except that a 1 mm concentration of the cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX (Calbiochem) was added for 35 min during incubation. The HTRF assay was also similar to that described for IP1, except that an anti-cAMP antibody and a d2-labeled cAMP analog were used.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed using an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antiserum against β1AR obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against synaptophysin 1 from Synaptic Systems (Göttingen, Germany). As a control for the immunochemical reactions, the primary antibodies were omitted from the staining procedure, whereupon no immunoreactivity resembling that obtained with the specific antibodies was detected.

Synaptosomes (0.67 mg/ml) were added to medium containing 0.32 m sucrose (pH 7.4) at 37 °C, allowed to attach to polylysine-coated coverslips for 1 h, and then fixed for 4 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 7.4) at room temperature. Following several washes with 0.1 m PB (pH 7.4), the synaptosomes were preincubated for 1 h in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) diluted in 50 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.9% NaCl (TBS) and 0.2% Triton X-100. Subsequently, they were incubated for 24 h with the appropriate primary antiserum for β1ARs (1:100) or synaptophysin (1:100), diluted in TBS with 1% NGS and 0.2% Triton X-100. After washing in TBS, the synaptosomes were incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in TBS for 2 h, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) and Alexa Fluor 594 Donkey anti-goat IgG (1:500), both obtained from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). After several washes in TBS, the coverslips were mounted with the Prolong Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes), and the synaptosomes were viewed using a Nikon Diaphot microscope equipped with a ×100 objective, a mercury lamp light source, and fluorescein-rhodamine Nikon filter sets.

For quantitative analysis, all images were acquired using identical settings with neutral density transmittance filters. Background subtraction was performed by applying a rolling ball algorithm (6 pixel radius), and the brightness and contrast settings were adjusted according to the negative control values using ImageJ version 1.39f (National Institutes of Health). The number of stained particles larger than 0.5 μm was quantified automatically from binary image masks, discarding the aggregates. Co-localization analysis was performed automatically by measuring the coincidence area of quantified particles in each pair of images within the same field.

Electron Microscopy and Synaptic Vesicle Distribution in Synaptosomes

Synaptosomes (0.67 mg/ml) were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in HBM containing 16 μm BSA and adenosine deaminase (1.25 units/mg protein). The βAR agonist isoproterenol (100 μm) and the Epac activator 8-pCPT-O′-Me-cAMP (50 μm) were added for 10 min prior to washing. Synaptosomes were washed by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 1 min) and fixed for 2 h at 4 °C with 4% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Millonig's sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.3). The synaptosomes were then washed twice and incubated overnight at 4 °C in Millonig's buffer, after which they were postfixed in 1% OsO4, 1.5% K3Fe(CN)6 for 1 h at room temperature and dehydrated in acetone. Synaptosomes were then embedded using the SPURR embedding kit (TAAB Laboratory Equipment Ltd., Reading, UK). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were routinely stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and images were obtained on a Jeol 1010 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan). Randomly chosen areas were then photographed at a final magnification of ×80,000. Measurements were taken using ImageJ software. The relative percentage of synaptic vesicles (SVs) per active zone was calculated in 10-nm bins at the active zone of the inner layer membrane. The total number of SVs per synaptic terminal was also determined. To better localize the active zone, only nerve terminals containing attached postsynaptic membranes were analyzed.

Immunoelectron Microscopy

Immunohistochemical reactions for electron microscopy were carried out using the pre-embedding immunogold method as described previously (35). Three adult C57BL/6 mice (P60) were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with ice-cold fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.05% glutaraldehyde, and 15% (v/v) saturated picric acid made up in 0.1 m PB (pH 7.4). After perfusion, the animal's brain was removed and washed thoroughly in 0.1 m PB, and 60-μm-thick coronal vibratome sections were obtained (Leica V1000). Free-floating sections were incubated in 10% (v/v) NGS diluted in TBS and then with goat β1AR antibodies (Sigma) at a final protein concentration of 3–5 μg/ml diluted in TBS containing 1% (v/v) NGS. After several washes in TBS, the sections were incubated with 1.4-nm gold-coupled rabbit anti-goat IgG (Nanoprobes Inc., Stony Brook, NY). The sections were postfixed in 1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and washed in double-distilled water, followed by silver enhancement of the gold particles with an HQ Silver kit (Nanoprobes Inc.). Sections were then treated with osmium tetraoxide (1% in 0.1 m PB), block-stained with uranyl acetate, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and flat-embedded on glass slides in Durcupan (Fluka) resin. Regions of interest were sliced at a thickness of 70–90 nm on an ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut E, Leica, Austria) and collected on single slot pioloform-coated copper grids. Staining was performed using drops of 1% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by Reynolds's lead citrate, and their ultrastructure was analyzed on a Jeol-1010 electron microscope.

Quantification of Adrenergic Receptors

To establish the relative abundance of β1AR subunits in layers III–V of the neocortex, we carried out the quantification of immunolabeling as follows. We used 60-μm coronal slices processed for pre-embedding immunogold immunohistochemistry. The procedure was similar to that used previously (35). Briefly, for each of three animals, three samples of tissue were obtained for preparation of embedding blocks. To minimize false negatives, ultrathin sections were cut close to the surface of each block. We estimated the quality of immunolabeling by always selecting areas with optimal gold labeling at approximately the same distance from the cutting surface. Randomly selected areas were then photographed from the selected ultrathin sections at a final magnification of ×45,000. Quantification of immunogold labeling was carried out in sampling areas of each cortex totaling ∼1,500 μm2. Immunoparticles identified for individual β1AR subunits in each sampling area and present along the plasma membrane axon terminals were counted. Only axon terminals establishing synaptic contacts with dendritic spines or shafts were included in the analysis. A total of 811 axon terminals were included in the sampling areas establishing clear synaptic contacts with postsynaptic elements. Of these axon terminals, only 155 axon terminals were immunopositive for β1AR, showing a total of 318 gold particles. Then the percentage of immunoparticles at the active zone and extrasynaptic plasma membrane of axon terminals for the β1AR subunits, as well as the percentage of β1AR-positive and β1AR-negative, was calculated.

Controls

To determine the specificity of the methods used in the immunoelectron microscopy studies, the primary antibody was either omitted or replaced with 5% (v/v) normal serum corresponding to the species of the primary antibody. No specific labeling was observed in these conditions. Labeling patterns were also compared with those obtained for calretinin and calbindin, and only antibodies against β1AR consistently labeled the plasma membrane.

Munc13-1 Translocation

Synaptosomes were resuspended (0.67 mg/ml) in HMB medium with 16 μm BSA and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, and adenosine deaminase (1.25 units/mg protein) was then added for another 20 min. The PLC inhibitors U73122 (active; 2 μm) and U73343 (inactive; 2 μm), and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX (1 mm) were added for 30 min prior to washing. Isoproterenol (100 μm) and the Epac activator 8-pCPT-O′-Me-cAMP (50 μm) were added for 10 min, and the phorbol ester phorbol dibutyrate (1 μm) was added for 2 min. Synaptosomes were washed by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 30 s) and resuspended (2 mg/ml) in hypo-osmotic medium (8.3 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4) containing the Protease Inhibitor Mixture Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL). The synaptosomal suspension was passed through a 22-gauge syringe to disaggregate the synaptosomes, which were then maintained at 4 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking. The soluble and particulate fraction were then separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 40,000 × g and 4 °C. The supernatant (soluble fraction) was collected, and the pellet (particulate fraction) was resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.2% SDS, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)). In soluble and particulate fractions, levels of marker proteins were analyzed either enzymatically (using acetylcholinesterase and lactate dehydrogenase) or by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Western blotting. Acetylcholinesterase activity was determined fluorometrically by the Ellman reaction in the presence of 0.75 mm acetylthiocholine iodide, 0.2 mm 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8). Lactate dehydrogenase activity was assayed following NADH oxidation in medium containing 1 mm pyruvate, 0.2 mm NADH, and 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence of 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100. The soluble fraction was characterized by a high lactate dehydrogenase content (76.8 ± 3.4%, n = 5) and low acetylcholinesterase content (19.1 ± 5.3%; n = 5). By contrast, the particulate fraction contained little lactate dehydrogenase (23.2 ± 3.4%, n = 5) but was enriched in acetylcholinesterase (80.9 ± 5.3%, n = 5). Soluble and particulate fractions (3 μg of protein/lane) were diluted in Laemmli loading buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (5% v/v), resolved by SDS-PAGE (7.5% acrylamide; Bio-Rad), and analyzed in Western blots according to standard procedures. All samples were normalized to the levels of β-tubulin (soluble and particulate fractions, respectively) in the same blot. Munc13-1 content was expressed as a percentage of the integrated intensity of total soluble and particulate fractions. Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies coupled to Odyssey IRDye 680 or Odyssey IRDye 800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) were used to quantify the Western blots using the Odyssey System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). The primary antibodies used to probe Western blots were a polyclonal rabbit anti-Munc13–1 (1:1000; Synaptic Systems) and a monoclonal mouse anti-β-tubulin (1:2000; Sigma).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Synaptosomes (0.67 mg/ml) in HBM containing 16 μm BSA and adenosine deaminase (1.25 units/mg protein) were incubated during 1 h at 37 °C before the Epac activator 8-pCPT-O′-Me-cAMP (50 μm) was added for 10 min. In some experiments, the PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 μm, 30 min) was added. Synaptosomes were collected by centrifugation at 13,000 × g and kept at −80 °C until used. Control and treated synaptosomes were solubilized with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for 30 min on ice. The solubilized extract was then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant (1 mg/ml) was processed for immunoprecipitation, each step of which was conducted with constant rotation at 0–4 °C. The supernatant was incubated overnight either with an affinity-purified rabbit anti-RIM1α polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems) or an IgG-purified mouse anti-Rab3 monoclonal antibody (clone 42.1; Synaptic Systems). Next, 50 μl of a suspension of protein A cross-linked to agarose beads (Sigma) was added, and the mixture was incubated for another 2 h. Subsequently, the beads were washed twice with ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and twice with the same buffer but diluted 1:10 with Tris-saline (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl). Then 100 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (0.125 m Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromphenol blue) was added to each sample, and the immune complexes were dissociated by adding fresh dithiothreitol (DTT; 50 mm final concentration) and heating to 90 °C for 10 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE on either 7 or 12% polyacrylamide gels, and they were transferred to PVDF membranes using a semidry transfer system. The membranes were then probed with the indicated primary antibody and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (Pierce) and detected in a LAS-3000 (FujiFilm Life Science, Woodbridge, CT).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Student's unpaired t test or ANOVA was used for statistical analysis as appropriate; p values are reported throughout, and significance was set as p < 0.05. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for the significance of cumulative probabilities.

RESULTS

Tetrodotoxin Isolates a PKA-independent Component of Forskolin-potentiated Glutamate Release

The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin is commonly used to increase intracellular cAMP levels and to enhance synaptic transmission (1, 4), principally via mechanisms that include the modulation of ion channels and/or the modulation of the release machinery. In the search for the best stimulating protocol to isolate the PKA-independent component of the cAMP-dependent release, nerve terminals were stimulated with KCl. Depolarizing nerve terminals with KCl opens voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and triggers glutamate release. Forskolin enhanced the release stimulated with a low (5 mm) KCl concentration (172.2 ± 2.9%, n = 6, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, A and B). The PKA inhibitor H-89 strongly reduced the forskolin-induced potentiation, although a significant potentiation of release was still observed (138.8 ± 3.2%, n = 10, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, A and B). Previous experiments with cerebrocortical nerve terminals and slices have shown that forskolin potentiation of evoked release relies on a PKA-dependent mechanism, whereas forskolin potentiation of spontaneous release is mediated by PKA-independent mechanisms (4, 9). To isolate the cAMP effects on the release machinery, we measured the spontaneous release that results from the spontaneous fusion of synaptic vesicles after blocking Na+ channels with tetrodotoxin to prevent action potentials. Forskolin increased the spontaneous release of glutamate (171.5 ± 10.3%, n = 4, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, C and D) by a mechanism largely independent of PKA activity, because a similar enhancement of release was observed in the presence of H-89 (162.0 ± 8.4%, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, C and D). However, the spontaneous release observed in the presence of tetrodotoxin was sometimes rather low, making difficult the pharmacological characterization of the response.

FIGURE 1.

Tetrodotoxin isolates a PKA-independent component of forskolin-potentiated glutamate release. The Ca2+-dependent release of glutamate induced by 5 mm KCl (A and B), the spontaneous release of glutamate in the presence of 1 μm tetrodotoxin (C and D), and the glutamate release induced by the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (0.5–1 μm) in the presence or absence of 1 μm tetrodotoxin added 2 min prior to ionomycin (E and F) were measured in the absence and presence of forskolin and in the absence and presence of the PKA inhibitor H-89. Forskolin (15 μm) was added 1 min prior to ionomycin. In experiments with the PKA inhibitor H-89 (10 μm), synaptosomes were incubated with the drug for 30 min. B, D, and F, diagrams summarizing the data pertaining to the potentiation of release under different conditions. Control release corresponds to that induced by 5 mm KCl, tetrodotoxin, ionomycin or by tetrodotoxin plus ionomycin alone. The specific PKA activator 6-Bnz-cAMP (500 μm) was added 1 min prior to ionomycin. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). NS, not significant (p > 0.05); ***, p < 0.001, compared with the control (symbols inside the bars) or with other conditions as indicated in the figure.

Alternatively, we used the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin, which inserts into the membrane and delivers Ca2+ to the release machinery independent of Ca2+ channel activity. The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin strongly potentiated ionomycin-induced release in cerebrocortical nerve terminals (272.1 ± 5.5%, n = 7, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, E and F), an effect that was only partially attenuated by the PKA inhibitor H-89 (212.9 ± 6.4%, n = 6, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, E and F). Although glutamate release was induced by a Ca2+ ionophore, and it was therefore independent of Ca2+ channel activity, it is possible that spontaneous depolarizations of the nerve terminals occurred during these experiments, promoting Ca2+ channel-driven Ca2+ influx. To investigate this possibility, we repeated these experiments in the presence of the Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin, and forskolin continued to potentiate glutamate release in these conditions (170.1 ± 3.8%, n = 9, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1, E and F). Interestingly, this release was now insensitive to the PKA inhibitor H-89 (177.4 ± 5.9%, n = 7, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 1, A and B).

Further evidence that tetrodotoxin isolates the PKA-independent component of the forskolin-induced potentiation of glutamate release was obtained in experiments using the cAMP analog 6-Bnz-cAMP, which specifically activates PKA. 6-Bnz-cAMP strongly enhanced glutamate release (178.2 ± 7.8%, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 1B) in the absence of tetrodotoxin, but it only had a marginal effect in its presence (112.9 ± 3.8%, n = 6, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 1B). Based on these findings, all subsequent experiments were performed in the presence of tetrodotoxin and ionomycin because these conditions isolate the H-89-resistant component of release potentiated by cAMP, and in addition, control release can be fixed to a value (0.5–0.6 nmol) large enough to allow the pharmacological characterization of the responses.

The Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin can induce a Ca2+-independent release of glutamate due to decreased ATP and increased depolarization, although this is unlikely to occur at the very low concentrations (0.5–1.0 μm) of ionomycin used in this study. Indeed, the presence of a release component resistant to the vacuolar ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin would be indicative of the existence of a non-vesicular and Ca2+-independent release. We found that the incubation of the nerve terminals with bafilomycin (1 μm, 45 min) reduces to virtually zero the ionomycin-induced release (0.02 ± 0.03 nmol of glutamate, n = 4) compared with untreated controls (0.58 ± 0.02, n = 3; Fig. 2A). Thus, the release of glutamate induced by ionomycin exclusively originates from a vesicular pool.

FIGURE 2.

The activation of β-adrenergic receptors and the Epac protein enhances PKA-independent glutamate release. A, glutamate release was induced by the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (0.5–1 μm) in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTx; 1 μm), added 2 min prior to ionomycin. The vacuolar ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin was added at 1 μm for 45 min. The βAR agonist isoproterenol (Iso; 100 μm) and the specific Epac activator 8-pCPT (50 μm) were added 1 min prior to ionomycin. B and D, the diagrams summarize the data pertaining to glutamate release under different conditions. Control release corresponds to that induced by ionomycin alone. The cAMP analog Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μm) and the phosphodiesterase-resistant 8-pCPT analog Sp-8-pCPT were added 1 min prior to ionomycin. The βAR antagonist propanolol (100 μm), the PKA inhibitor H-89 (10 μm), the HCN channel blocker ZD7288 (60 μm), and the GDP-GTP exchange inhibitor brefeldin A (BFA; 100 μm) were added 30 min prior to ionomycin. C, changes in cAMP levels induced by forskolin and isoproterenol. Results are presented as the -fold increase compared with the basal cAMP levels in control synaptosomes (3.3 ± 0.4 pmol/mg). E and F, the addition of forskolin plus 8-pCPT or isoproterenol plus 8-pCPT resulted in a subadditive response indicating occlusion. Diagrams show release induced by forskolin (15 μm), 8-pCPT (50 μm). or isoproterenol (100 μm), alone or in combination (Fsk/8-pCPT or Iso/8-pCPT). Dashed lines, the sum of individual Fsk and 8-pCPT responses or Iso and 8-pCPT responses. Solid lines represent the response when the two activators were added in combination. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). NS, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with the control (symbols inside the diagram) or the other conditions indicated in the figure.

The Activation of β-Adrenergic Receptors and the Epac Protein Enhances PKA-independent Glutamate Release

Whereas Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase isoforms are expressed at nerve terminals, all adenylyl cyclase isoforms are stimulated by G proteins (29). Therefore, receptor coupling to Gs and to cAMP-dependent pathways would be expected at the presynaptic level. Previous studies have demonstrated that the βAR agonist isoproterenol enhances cAMP levels, evoked glutamate release (4, 32), and evoked synaptic transmission (8). We found that in the presence of tetrodotoxin, isoproterenol enhanced ionomycin-induced release (173.1 ± 3.8%, n = 23, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 2, A and B), an effect that was abolished in the presence of the βAR antagonist propanolol (106.5 ± 3.1%, n = 6, p > 0.05, ANOVA) but not by the PKA inhibitor H-89 (178.1 ± 3.3%, n = 7, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 2B). Hence, the response to isoproterenol in the presence of tetrodotoxin is fully PKA-independent. Importantly, isoproterenol qualitatively but not quantitatively mimicked the potentiating effect of forskolin on glutamate release. Thus, the maximum release induced by isoproterenol (100 μm) was equivalent to that induced by a submaximal concentration of forskolin (15 μm). Significantly greater glutamate release was obtained with maximal concentrations (100 μm) of forskolin (288.3 ± 6.3%, n = 4; data not shown), suggesting that the expression of βARs may be restricted to a subpopulation of adenylyl cyclase-containing nerve terminals. Indeed, the cAMP analog Sp-8-Br-cAMPS mimicked the potentiating effect of isoproterenol on ionomycin-induced glutamate release (175.5 ± 3.2%, n = 11, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 2B). Moreover, the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin increased cAMP levels (451.6 ± 41.7%, n = 5, p < 0.001, Student's t test; Fig. 2C), as did isoproterenol, albeit to a lesser extent (194.2 ± 24.2%, n = 6, p < 0.001; Student's t test), indicating that βARs mediate increases in cAMP levels.

By intracellularly opening HCN channels, cAMP may, in turn, increase nerve terminal depolarization and thereby enhance glutamate release. The HCN channel blocker ZD7288 (36) had no effect on isoproterenol-induced glutamate release (175.0 ± 3.8%, n = 4, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 2B), excluding a role for HCN channels in this response. Epac1 and Epac2 are cAMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factors for the small GTPases Rap1 and Rap2, and they are important mediators of the actions of cAMP (22). The specific membrane-permeant Epac activator 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (8-pCPT) enhanced ionomycin-induced glutamate release (180.1 ± 4.3%, n = 8, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 2, A and D), an effect that was resistant to PKA inhibition with H-89 (180.2 ± 9.4%, n = 3, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 2D). The effect of the Epac activator 8-pCPT was validated by the use of the phosphodiesterase-resistant 8-pCPT analog, Sp-8-pCPT, which enhanced ionomycin-induced glutamate release to a similar extent (193.4 ± 5.5%, n = 8, p < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 2D). If Epac proteins mediate forskolin-potentiated glutamate release at some point downstream of cAMP, then the response to the Epac activator 8-pCPT should be occluded by forskolin. In support of this hypothesis, there was a weaker response to the combined addition of forskolin and 8-pCPT (196.8 ± 1.9%, n = 6, p < 0.001, ANOVA) than the sum of the individual responses (8-pCPT, 180.1 ± 4.3%, n = 8; forskolin, 168.5 ± 3.0%, n = 6; Fig. 2E), suggesting that both compounds enhance glutamate release via the same signaling pathway. Similar results were obtained when the Epac activator 8-pCPT was combined with the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (Fig. 2F). The GDP-GTP exchange inhibitor brefeldin A (BFA), which inhibits Epac responses (36), reduced the responses induced by 8-pCPT (122.3 ± 5.5%, n = 6, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 2D), isoproterenol (133.2 ± 3.8%, n = 6, p < 0.05, ANOVA), and the cAMP analog Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (133.7 ± 5.5%, n = 3, p < 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 2B).

In parallel experiments in which the spontaneous release of glutamate was determined by blocking Na+ channels with tetrodotoxin, but in the absence of ionomycin, we found that the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol and the Epac activator 8-pCPT both enhanced the H-89-resistant component of spontaneous release (135.5 ± 6.3%, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA and 154.3 ± 3.1%, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA, respectively).

The Activation of β-Adrenergic Receptors and the Epac Protein Activates PLC

In non-neuronal secretory systems, Epac2 is linked to the activation of PLC-ϵ and the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) (25, 26, 28), resulting in the production of IP3 and DAG. We investigated whether pharmacological inhibition of PLC activity altered isoproterenol-induced glutamate release. Interestingly, the facilitatory action of isoproterenol was significantly reduced in the presence of the PLC inhibitor U73122 (136.4 ± 7.2%, n = 7, p < 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 3, A and B), whereas its inactive analog U73343 had no such effect (167.5 ± 5.5%, n = 7, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 3B). 8-pCPT-induced release was reduced by U73122 (126.1 ± 4.4%, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA) but not by U73343 (162.3 ± 6.2%, n = 3, p > 0.05; Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

β-Adrenergic receptors and Epac proteins activate PLC. A, glutamate release was induced by the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (0.5–1 μm) in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTx; 1 μm) added 2 min prior to ionomycin. The βAR agonist isoproterenol (Iso; 100 μm) was added 1 min prior to ionomycin. The PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 μm), the PKC inhibitor calphostin C (0.1 μm), and bisindolylmaleimide (1 μm) were added 30 min prior to the ionomycin. B and C, the diagrams summarize the data pertaining to release potentiation under different conditions. Control release corresponds to that induced by ionomycin alone. The specific Epac activator 8-pCPT (50 μm) was added 1 min prior to ionomycin. The inactive PLC inhibitor U73343 (2 μm) and the calmodulin antagonist calmidazolium (1 μm) were added 30 min prior to ionomycin. D, isoproterenol and 8-pCPT increased the accumulation of IP1. Synaptosomes were incubated for 10 min with isoproterenol (100 μm) and 8-pCPT (50 μm). The PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 μm) was added 30 min prior to isoproterenol or 8-pCPT. The results are presented as the -fold increase relative to the basal IP1 levels in control nerve terminals (4.6 ± 0.4 pmol/mg) and in U73122-treated synaptosomes (2.4 ± 0.3 pmol/mg). The data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). NS, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with the control (symbols inside the diagram) or other conditions indicated in the figure.

Based on these findings, we investigated the role of PIP2 hydrolysis and the subsequent formation of DAG and IP3 in this process. The activity of PLC-linked GPCRs can be monitored by measuring the accumulation of IP1 rather than that of IP3 following LiCl inhibition (34). Isoproterenol increased the accumulation of IP1 (143.7 ± 10.5%, n = 12, p < 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 3D), an effect that was abolished by the PLC inhibitor U73122 (99.3 ± 2.4%, n = 6, p > 0.05, ANOVA). The Epac activator 8-pCPT also increased IP1 accumulation (165.5 ± 11.5%, n = 6, p < 0.01, ANOVA) in a manner sensitive to the PLC inhibitor U73122 (100.5 ± 3.5%, n = 4, p > 0.05; Fig. 3D). These data indicate that βARs and Epac activate PLC in nerve terminals, implicating this signaling pathway in the potentiating effects of βARs on glutamate release.

Because isoproterenol and Epac proteins enhance PIP2 hydrolysis to generate IP3 and DAG, we next investigated the sensitivity of release facilitation to protein kinase C inhibitors. Bisindolylmaleimide, a specific inhibitor of protein kinase C that prevents ATP binding, had no effect on the facilitatory effects of isoproterenol (167.4 ± 3.4%, n = 8, p > 0.05) or Epac (167.4 ± 3.4%, n = 8, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 3, A–C), whereas calphostin C reduced the facilitation of glutamate release by both isoproterenol (132.9 ± 7.3%, n = 7, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 3, A and B) and 8-pCPT (135.8 ± 5.5%, n = 6, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 3C). In addition to preventing diacylglycerol binding, calphostin C inhibits non-kinase DAG-binding proteins, such as the Munc13 family (37). Munc13 proteins play a key role in the priming of synaptic vesicles for release, and they are activated by calmodulin as well as by DAG and Ca2+ (38). The facilitatory effect of isoproterenol on glutamate release was reduced by the calmodulin antagonist calmidazolium (129.1 ± 3.3, n = 7, p < 0.01, ANOVA), and it was abolished when calmidazolium was administered in combination with calphostin C (101.1 ± 3.0%, n = 7, p > 0.05; Fig. 3B). Similarly, the facilitatory effect of the Epac agonist 8-pCPT on glutamate release was reduced by the calmodulin antagonist calmidazolium (142.4 ± 2.9%, n = 6, p < 0.05, ANOVA), and it was abolished when calmidazolium was administered in combination with calphostin C (107.7 ± 4.4%, n = 7, p > 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 3C). However, it remains to be determined whether Munc13 is the only calmidazolium-sensitive component of the βAR-activated pathway.

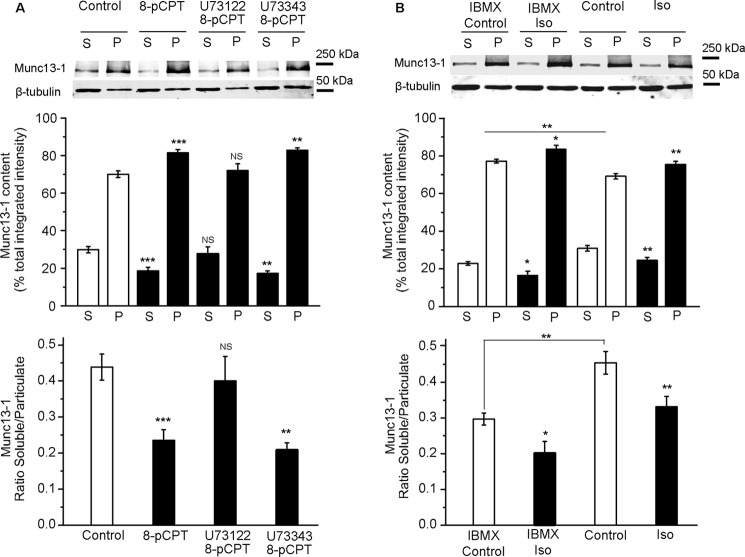

The Activation of β-Adrenergic Receptors and Epac Promotes Munc13-1 Translocation

The active zone protein Munc13-1 is a phorbol ester receptor essential for synaptic vesicle priming, and it plays an important role in the potentiation of neurotransmitter release (39–41). Munc13-1 is distributed in two biochemically distinguishable soluble and insoluble pools (39, 42, 43). Because diacylglycerol and phorbol esters increase the association of Munc13-1 to the plasma membrane (37), we investigated whether the activation of βAR or Epac altered the subcellular distribution of Munc13-1 in the soluble and particulate fractions derived from synaptosomes after hypo-osmotic shock (which are enriched in cytosolic/plasma membrane and vesicular proteins, respectively) (44). The Munc13-1 content in the soluble and particulate fractions was determined in Western blots, and the soluble/particulate Munc13-1 ratio in control nerve terminals was 0.46 ± 0.04 (n = 10). This value decreased significantly following exposure to the Epac activator 8-pCPT (0.24 ± 0.03, n = 10, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 4A), indicating translocation of the Munc13-1 protein from the soluble to the particulate fraction. This shift was prevented by the PLC inhibitor U73122 (0.40 ± 0.07, n = 5, p > 0.05, ANOVA) but not by its inactive counterpart U72343 (0.20 ± 0.03, n = 5, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 4A). Isoproterenol translocated Munc13-1 to the particulate fraction (0.33 ± 0.03, n = 13, p < 0.01, Student's t test; Fig. 4B) in the absence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. In the presence of IBMX, the subcellular distribution of Munc13 (0.30 ± 0.02, n = 6) was also shifted from soluble to particulate fractions by isoproterenol (0.20 ± 0.03, n = 6, p < 0.05, Student's t test; Fig. 4B). Phorbol dibutyrate served as a positive control and induced strong Munc13-1 translocation (soluble/particulate ratio 0.12 ± 0.02, n = 9, p < 0.01; data not shown). Overall, these data indicate that Epac protein activation promotes the translocation of Munc13-1 protein from the soluble to the particulate fraction within nerve terminals and that increases in cAMP by βAR agonist isoproterenol promoted Munc13-1 translocation.

FIGURE 4.

The activation of β-adrenergic receptors and the Epac protein promotes the translocation of the Munc13-1 protein. Shown is Munc13-1 protein content in the soluble (S) and particulate (P) fractions of control synaptosomes and those stimulated with the specific Epac activator 8-pCPT (50 μm, 10 min) (A) or isoproterenol (100 μm, 10 min) (B) in the presence or absence of active U73122 (2 μm, 30 min) or inactive U73343 (2 μm, 30min). When indicated, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX (1 mm, 30 min) was added. The top diagrams show the quantification of Munc-13-1 content in the soluble and particulate fractions of the synaptosomes. The sum of the soluble and particulate fraction values was taken as 100%. The ratio of Munc13-1 content in soluble versus particulate fractions was calculated in each experiment and is shown in the bottom panels. The data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). NS, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with either the soluble or particulate fraction or the soluble/particulate ratio in control synaptosomes.

Epac Activation Enhances the Interaction between Rab3 and RIM Proteins

In non-neuronal preparations, Epac proteins activate small G proteins like Rap1 and Rab3 (24) and then bind to the active zone protein RIM (27, 45). Small G proteins cycle between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states (46). Rab3 proteins are attached to synaptic vesicles in their GTP-bound state and serve as key modulators of neurotransmitter release. The N-terminal sequence of RIM (a Rab-interacting molecule) mediates its simultaneous binding to Munc13 and Rab3, where it acts as a priming factor and a vesicular GTP-binding protein, respectively (47). It has been suggested that this ternary Rab3/RIM/Munc13 interaction approximates synaptic vesicles to the synaptic machinery. Accordingly, we aim to test whether Epac activation enhanced the interaction between. To this end, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in soluble cerebrocortical synaptosome extracts that had been shown by Western blotting to contain both RIM1α and Rab3A (Fig. 5A, Crude). The anti-Rab3A antibody was able to immunoprecipitate a band of ∼25 kDa, which apparently corresponded to Rab3A protein, as expected. The amount of immunoprecipitated Rab3A was unaffected by the treatment of synaptosomes with either 8-pCPT or U73122 (Fig. 5A, IP: Rab3A). Interestingly, the anti-RIM1α antibody was able to immunoprecipitate from soluble cerebrocortical synaptosome extract a band corresponding to Rab3 protein (Fig. 5A, IP: Rim1α). This band did not appear when an irrelevant rabbit IgG was used for immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A, IP: IgGr), showing that the reaction was specific and that the detected band indeed corresponded to Rab3A protein. Moreover, when the synaptosomes were pretreated with 8-pCPT, an apparent increase in the amount of immunoprecipitated Rab3A was observed (Fig. 5A, IP: Rim1α). Thus, quantification of the corresponding Western blots showed a significant increment (122 ± 6%, n = 3, p < 0.05, ANOVA) of the Rab3A immunoprecipitated with anti-RIM1α antibody when the synaptosomes were incubated in the presence of the Epac cAMP receptor 8-pCPT. The PLC inhibitor U73122 did not change the Rab3 immunoprecipitated (86 ± 3%, n = 3, p > 0.05, ANOVA) but prevented the increase of immunoprecipitated Rab3 induced by 8-pCPT (99 ± 6%, n = 3, p > 0.05, ANOVA). Overall, these results suggested that the Rab3A and RIM1α protein might assemble into stable protein-protein complexes in the rat cortex that survive the solubilization and co-immunoprecipitation conditions employed. The stability of these oligomeric complexes indicates that they might be physiologically relevant in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

Epac activation enhances Rab3A-RIM1α interaction in cerebrocortical synaptosomes. A, co-immunoprecipitation of Rab3A and RIM1α. Cerebrocortical synaptosomes were incubated in the absence or the presence of 8-pCPT (50 μm) and in the absence and presence of the PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 μm), solubilized and subjected to immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-FLAG antibody (4 μg; IP: IgGm), mouse anti-Rab3A antibody (4 μg; IP: Rab3A), rabbit anti-FLAG antibody (4 μg; IP: IgGr), and rabbit anti-RIM1α antibody (4 μg; IP: Rim1α). Extracts (Crude) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed in Western blots (IB) probed with mouse anti-Rab3A antibody (1 μg/ml). Immunoreactive bands were detected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, quantification of 8-pCPT-induced Rab3A-Rim1α interaction in the absence and presence of U73122. The ratio between Rab3A immunoprecipitated with anti-Rim1α and anti-Rab3A (IP ratio) was calculated and normalized to the IP ratio found in the untreated cerebrocortical synaptosomes (Control). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate data significantly different from the control condition. NS, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.01.

The Activation of β-Adrenergic Receptors and the Epac Protein Promotes the Approximation of Synaptic Vesicles to the Active Zone

The data presented above demonstrate that βAR and Epac activation promotes the translocation of the Munc13-1 protein and enhances the interaction between Rab3 and RIM, three proteins known to form a complex essential for priming SVs to a release-competent state (47). Thus, we assessed whether βAR and Epac increased the number of SVs in the vicinity of the active zone by performing electron microscopy on synaptosomes. Exposure of synaptosomes to isoproterenol and 8-pCPT significantly increased the proportion of synaptic vesicles within 10 nm of the active zone plasma membrane (controls, 4.6 ± 0.6%, n = 76; isoproterenol-treated synaptosomes, 7.5 ± 0.8%, n = 48, p < 0.001, Student's t test; 8-pCPT-treated synaptosomes, 9.3 ± 1.4%, n = 42, p < 0.001, Student's t test; Fig. 6, A–C, E, and F) without altering the total number of SVs per active/release site (controls, 30.7 ± 2.4; isoproterenol-treated synaptosomes, 33.3 ± 3.1, p > 0.05, Student's t test; 8-pCPT-treated synaptosomes, 35.3 ± 3.5, p > 0.05, Student's t test; Fig. 6D). Furthermore, isoproterenol and 8-pCPT significantly modified cumulative probability of SV distribution within 10 nm of the active zone plasma membrane. Hence, the functional and biochemical changes induced by the βAR and Epac protein correlate with the structural changes associated with the redistribution of SVs closer to the active zone in the presynaptic membrane.

FIGURE 6.

β-Adrenergic receptor and Epac activators increase the proportion of synaptic vesicles close to the active zone. Shown are electron micrographs of cortical synaptosomes in control conditions (A) and after treatment with isoproterenol (100 μm, 10 min) (B) or 8-pCPT (50 μm, 10 min) (C). D, mean number of total SVs per active zone. Shown are quantifications of the spatial distribution of SVs per active zone in synaptosomes treated with isoproterenol (E) or 8-pCPT (F). Scale bar, 150 nm. G, cumulative probability of the isoproterenol and 8-pCPT effects on the percentage of SVs closer than 10 nm to the active zone plasma membrane. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). NS, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with the corresponding control values.

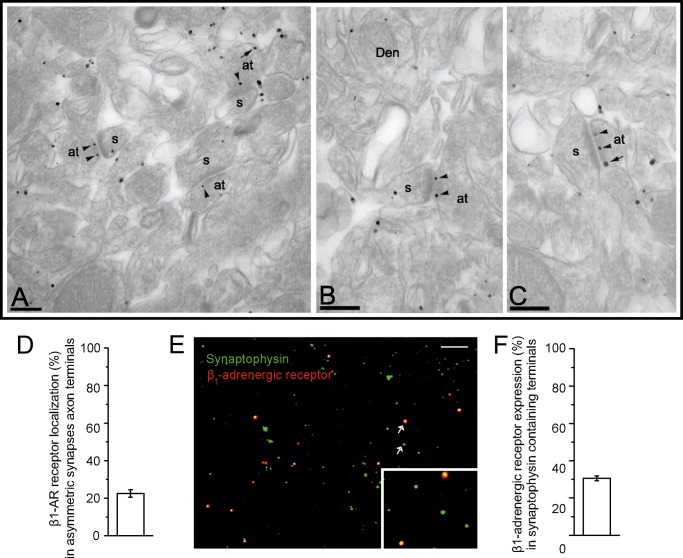

β1-Adrenergic Receptors Are Expressed Presynaptically

The βAR agonist isoproterenol mimics forskolin in potentiating glutamate release, suggesting that these receptors are expressed presynaptically at glutamatergic terminals. Moreover, βAR immunoreactivity at presynaptic specializations, as occasionally observed by electron microscopy, may be associated with catecholaminergic neurons (48). Accordingly, we analyzed the precise subcellular localization of this receptor in putative asymmetric glutamatergic synapses.

We used immunoelectron microscopy to assess the subcellular localization of β-adrenergic receptor 1 subunits in axon terminals of the neocortex. Fig. 7, A–C, shows a representative image of the β-adrenergic receptor in layers III–V of the cortex, as detected using a pre-embedding immunogold technique. The β-adrenergic receptor is expressed postsynaptically in spines and dendrites as well as presynaptically. At the presynaptic level, the β1AR was detected in around 19% of all axon terminals analyzed. In these immunopositive β1ARs, most of the labeling was found in axons establishing asymmetrical, putative glutamatergic synapses, mostly in the active zone (274 of 318 immunoparticles) and also at extrasynaptic sites (44 of 318 immunoparticles) (Fig. 7, A–C). The β1 adrenergic receptor was expressed in 22.5 ± 2.1% of asymmetrical synapse axon terminals (474 synapses from three cortices; Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

β1-Adrenergic receptor subunits are mainly localized at presynaptic sites in the cortex. A–C, representative images of the βAR in layers III–V of the cortex detected by pre-embedding immunogold staining. Immunoparticles for the β1AR were mainly detected at the active zone (arrowheads) and along the extrasynaptic membrane (arrows) of axon terminals (at), where they established excitatory synapses with dendritic spines (s) and at postsynaptic sites on both the spines and dendritic shafts (Den) of cortical pyramidal cells. Scale bars, 0.2 μm. D, quantification of the localization of β1AR subunits (percentage) to asymmetric synapses at axon terminals. E, images show synaptosomes fixed onto polylysine-coated coverslips and double-stained with antisera against the β1AR and the vesicular marker synaptophysin. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars). Scale bar, 10 μm. F, quantification of βAR expression in synaptophysin-containing nerve terminals.

We also determined the expression of the β1AR immunocytochemically by labeling synaptosomes with antisera against the vesicle marker synaptophysin and the β1AR. We found that 30.0 ± 1% of nerve terminals containing synaptophysin (2,290 synaptic boutons from 25 fields) also expressed the β1AR (Fig. 7, E and F). In synaptosomal preparations, glutamatergic nerve terminals accounted for 79.8% of the synaptophysin-positive particles (49), and we identified similar proportions of glutamatergic nerve terminals expressing β1ARs by electron microscopy and immunocytochemistry.

DISCUSSION

By blocking Na+ channels at cerebrocortical nerve terminals with tetrodotoxin, we describe here the isolation of a PKA-independent component of forskolin-potentiated glutamate release. The activation of the Epac protein with 8-pCPT mimicked this forskolin-mediated response, which involved PLC activation, translocation of the active zone Munc13-1 protein from the soluble to the particulate fraction, and the approximation of SVs to the presynaptic membrane. In addition, 8-pCPT promoted the association of Rab3A with the active zone protein RIM1α. Finally, we demonstrated the coupling of βARs to this cAMP/Epac/PLC/Munc13/Rab3/RIM-dependent pathway to enhance glutamate release.

Glutamatergic Synaptic Boutons Express β1-Adrenergic Receptors

The βAR agonist isoproterenol mimics forskolin in potentiating glutamate release, consistent with our observation of β1AR subunits at axon terminals that establish asymmetric putative glutamatergic synapses. Presynaptic labeling revealed that βARs were mainly located in the active zone, from where they modulate the release machinery. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies showed that βARs were only expressed in a fraction of cerebrocortical synaptic boutons, whereas functional data demonstrated that βAR-induced release was less than that induced by a maximal concentration of forskolin, suggesting that other receptors or presynaptic signals may also activate PKA-independent Epac-dependent pathways in our experimental conditions. There are abundant functional data supporting the existence of presynaptic βARs. For example, isoproterenol-induced increases in synaptic transmission, in several brain areas, are consistently associated with a decrease in paired pulse facilitation and/or an increase in the frequency of miniature or spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents, without significantly affecting their amplitude (20, 31). However, there is no structural evidence demonstrating the subcellular localization of βARs to support these functional findings. Although βAR labeling has been described in presynaptic membrane specializations, these receptors were expressed by catecholaminergic neurons, because they were co-labeled with antiserum against the catecholamine-synthesizing enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (48).

The finding that β1-adrenergic receptors are expressed in a subset of cerebrocortical nerve terminals is in agreement with functional experiment looking at SVs redistribution. Thus, isoproterenol redistributes SVs to closer positions to the active zone plasma membrane in around 20% of the nerve terminals (Fig. 6G), which is very close to the subset of nerve terminals found to express the receptor both in immunoelectron microscopy and immunocytochemical experiments.

β-Adrenergic Receptors Enhance Glutamate Release via a PKA-independent, Epac-dependent Mechanism

We previously reported that forskolin potentiates tetrodotoxin-sensitive Ca2+-dependent glutamate release in cerebrocortical synaptosomes (4, 6). This effect was PKA-dependent because it was blocked by the protein kinase inhibitor H-89, and it was associated with an increase in Ca2+ influx. Here, we demonstrate that forskolin also stimulates a tetrodotoxin-resistant component of release that is insensitive to the PKA inhibitor H-89. This response was mimicked by specific activation of Epac proteins with 8-pCPT. Moreover, Epac activation largely occluded both forskolin and isoproterenol-induced release, suggesting that these compounds activate the same signaling pathways. PKA is not the only target of cAMP, and Epac proteins have emerged as multipurpose cAMP receptors that may play an important role in neurotransmitter release (9), although their presynaptic targets remain largely unknown. Epac proteins are guanine nucleotide exchange factors that act as intracellular receptors of cAMP. These proteins are encoded by two genes, and the Epac1 and Epac2 proteins are widely distributed throughout the brain. Several studies have shown that cAMP enhances synaptic transmission via a PKA-independent mechanism in the calyx of Held (5, 7), whereas others have described presynaptic enhancement of synaptic transmission by Epac. Spontaneous and evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons from the hippocampus are dramatically reduced in Epac null mutants, an effect that is mediated presynaptically as the frequency but not the amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents is altered (50). Epac null mutants also exhibit short but not long term potentiation in CA1 pyramidal neurons from the hippocampus in response to tetanus stimulation (50). In the calyx of Held, the application of Epac to the presynaptic cell mimics the effect of cAMP, potentiating synaptic transmission (7). Finally, in hippocampal neural cultures, Epac activation fully accounts for the forskolin-induced increase in miniature excitatory postsynaptic current frequency (9).

β-Adrenergic Receptors Target the Release Machinery through the Activation of Epac Protein

Despite the remarkable advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for neurotransmitter release, very little is known of the mechanisms by which presynaptic receptors target release machinery components to regulate presynaptic activity. Here, we reveal an important link between βARs and the release machinery apparatus, given that βAR activation promoted the translocation of the active zone Munc13-1 protein from the soluble to particulate fractions in cerebrocortical synaptosomes. We also found that βAR and Epac activation stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis and that βAR- and Epac-mediated increases in glutamate release were partially prevented by PLC inhibitors. Hence, it would appear that the DAG generated by βARs can enhance neurotransmitter release through DAG-dependent activation of either PKC or Munc13 (51). βAR-mediated glutamate release was unaffected by the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide, but it was partially sensitive to calphostin C, which also inhibits non-kinase DAG-binding proteins, such as Munc13-1. These findings suggest that the DAG generated by βAR activation contributes to the activation/translocation of Munc13-1, which contains a C1 domain that binds DAG and phorbol esters (52, 53). Members of the Munc13 family (Munc13-1, Munc13-2, and Munc13-3) are brain-specific presynaptic proteins (42) that are essential for synaptic vesicle priming to a fusion-competent state (54, 55) and for short term potentiation of transmitter release (40, 56). Cerebrocortical nerve terminals express either Munc13-1 or Munc13-2, or a combination of both proteins (57). Although most glutamatergic hippocampal synapses express Munc13-1, a small subpopulation express Munc13-2 (56), yet phorbol ester analogs of DAG potentiate synaptic transmission at both types of synapse (56). Our finding that βAR and Epac activation enhances glutamate release is consistent with an increase in synaptic vesicle priming, activation of both promoting PIP2 hydrolysis, Munc13-1 translocation, and an increase in the number of synaptic vesicles at the plasma membrane in the vicinity of the active zone. However, whereas the PLC inhibitor U73122 abolishes the effects of βAR and Epac activation on PIP2 hydrolysis and Munc13-1 translocation, it only partially attenuated its effect on glutamate release, suggesting an additional Epac-mediated signaling module that is independent of PLC. Epac proteins have been shown to activate PLC. Indeed, βARs expressed in HEK-293 cells promote PLC activation and Ca2+ mobilization via a Rap GTPase, specifically Rap2B, which is activated by Epac (28). Epac activation also induces phospholipase C-dependent Ca2+ mobilization in non-neuronal secretory systems, such as human sperm suspensions (24), whereas Epac-induced insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells is lost in PLCϵ knock-out mice (26).

Our finding that Epac increases the association between Rab3A and RIM1α reveals another link between βARs and proteins of the release machinery. Although the enhanced interaction between Rab3A and RIM1α may be a consequence of the Epac-induced translocation of Munc13, three proteins known to form a tripartite complex essential for vesicle priming (47), Epac proteins can activate additional signaling pathways that involve small G proteins, including Rab3A. Rab3A is a small GTP-binding protein that attaches reversibly to the membrane of synaptic vesicles (58), and it cycles between a vesicle-associated GTP-bound form and a cytosolic GDP-bound form (59). GTP-bound Rab3A facilitates the docking of vesicles to the plasma membrane (60). Electrophysiological studies in the hippocampal CA1 region of mice lacking the Rab3A protein have demonstrated increased synaptic depression after short trains of repetitive stimuli (61). Rab3 also serves to redistribute crucial presynaptic active zone components that influence the efficacy of individual release sites (62). One possibility is that Epac proteins enhance the activation of Rab3A by promoting the formation of the GTP-bound active form, enhancing its interaction with other active zone proteins, including RIM1α. Such behavior would contribute to the formation of the tripartite Rab3A-RIM1α-Munc13 complex, which in turn would increase the priming of vesicles to a release-competent state. In support of this hypothesis, Epac proteins activate the small G proteins Rap1 and Rab3A to induce exocytosis in non-neuronal systems (24), whereas Epac2 interacts with RIM2 to promote insulin secretion in a cAMP-dependent, PKA-independent manner in pancreatic β cells (27, 45, 63).

Both αRIMs are Rab3 effectors, which are most abundantly expressed in mammals as RIM1α and RIM2 isoforms (12, 64, 65). The αRIMs are required for synaptic vesicle priming and short and long term synaptic plasticity (66–69). RIMs tether Ca2+ channels to the presynaptic active zone (70), and they activate vesicle priming by reversing the autoinhibitory homodimerization of Munc13 (71). Consistent with this central role, the deletion of RIM proteins ablates neurotransmitter release (70). αRIM proteins are key organizers of the active zone because they directly or indirectly interact with all other known active zone proteins, including the Rab3A and Munc13 proteins (47). Accordingly, selective disruption of the αRIM-Munc13-1 interaction decreases the size of the ready releasable vesicle pool in the calyx of Held synapse (47). The enhanced interaction of Rab3A and RIM1α described in the present study following Epac activation may reflect an increase in the formation of the tripartite Rab3A-RIM-Munc13 complex and in the priming of SVs. This proposal is consistent with our functional and structural data demonstrating that the activation of βARs and Epac enhances glutamate release, increasing the number of vesicles in the vicinity of the presynaptic plasma membrane.

In conclusion, βARs at nerve terminals increase cAMP levels and initiate a PKA- independent response that involves PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2 stimulated by Epac activation. This results in the production of DAG, which in turn activates/translocates the Munc13-1 protein to the active zone. Furthermore, the activation of βARs enhances the interaction between Rab3A and RIM1a (see scheme in Fig. 8). Thus, βARs recruit proteins that are essential to prime SVs to a release-competent state, increasing the proportion of SVs in the vicinity of the presynaptic membrane and the subsequent release of glutamate.

FIGURE 8.

β-Adrenergic receptors potentiate glutamate release at cerebrocortical nerve terminals. Shown is a scheme illustrating the putative signaling pathway activated by βARs. The βAR agonist isoproterenol stimulates the Gs protein, adenylyl cyclase thereby increasing cAMP levels. cAMP in turn activates Epac, which can promote PLC-dependent PIP2 hydrolysis to produce DAG. This DAG activates and translocates Munc13-1, an active zone protein essential for synaptic vesicle priming. Activation of the Epac protein also enhances the interaction between the GTP-binding protein Rab3A and the active zone protein Rim1α. These events promote the subsequent release of glutamate in response to Ca2+ influx. AC, adenylate cyclase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Agustín Fernández and Marisa García from the electron microscopy facility at the Universidad Complutense Madrid, and we thank María del Carmen Zamora for excellent technical assistance. We thank Dr. M. Sefton for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia Grants BFU2010-16947 (to J. S.-P.) and SAF2011-24779 and CSD2008-00005 (to F. C.) and CONSOLIDER (CSD2008-00005) (to R. L. and F. C.), Instituto de Salud Carlos III Grants RD06/0026 and RD12/0014, and Comunidad de Madrid Grant CAM-I2M2 2011-BMD-2349 (to J. S.-P. and M. T.).

- RIM

- Rab3-interacting molecule

- Epac

- exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- βAR

- β-adrenergic receptor

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- IP3

- inositol trisphosphate

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- HBM

- HEPES-buffered medium

- IP3

- inositol trisphosphate

- IP1

- inositol monophosphate

- NGS

- normal goat serum

- IBMX

- 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- SV

- synaptic vesicle

- 8-pCPT

- 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate monosodium hydrate

- 6-Bnz-cAMP

- N6-benzoyladenosine- 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- Sp-8-Br-cAMPS

- 8-bromoadenosine-3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Sp-isomer; Sp-8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate; Sp-isomer

- HCN channel

- hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel

- PB

- phosphate buffer

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chavez-Noriega L. E., Stevens C. F. (1994) Increased transmitter release at excitatory synapses produced by direct activation of adenylate cyclase in rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurosci. 14, 310–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weisskopf M. G., Castillo P. E., Zalutsky R. A., Nicoll R. A. (1994) Mediation of hippocampal mossy fiber long-term potentiation by cyclic AMP. Science 265, 1878–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Capogna M., Gähwiler B. H., Thompson S. M. (1995) Presynaptic enhancement of inhibitory synaptic transmission by protein kinases A and C in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J. Neurosci. 15, 1249–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herrero I., Sánchez-Prieto J. (1996) cAMP-dependent facilitation of glutamate release by β-adrenergic receptors in cerebrocortical nerve terminals. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30554–30560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakaba T., Neher E. (2001) Preferential potentiation of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles by cAMP at the calyx of Held. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 331–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Millán C., Torres M., Sánchez-Prieto J. (2003) Co-activation of PKA and PKC in cerebrocortical nerve terminals synergistically facilitates glutamate release. J. Neurochem. 87, 1101–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaneko M., Takahashi T. (2004) Presynaptic mechanism underlying cAMP-dependent synaptic potentiation. J. Neurosci. 24, 5202–5208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang C. C., Hsu K. S. (2006) Presynaptic mechanism underlying cAMP-induced synaptic potentiation in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 846–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gekel I., Neher E. (2008) Application of an Epac activator enhances neurotransmitter release at excitatory central synapses. J. Neurosci. 28, 7991–8002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fykse E. M., Li C., Südhof T. C. (1995) Phosphorylation of rabphilin-3A by Ca2+/calmodulin- and cAMP-dependent protein kinases in vitro. J. Neurosci. 15, 2385–2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Camilli P., Benfenati F., Valtorta F., Greengard P. (1990) The synapsins. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 6, 433–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y., Okamoto M., Schmitz F., Hofmann K., Südhof T. C. (1997) Rim is a putative Rab3 effector in regulating synaptic-vesicle fusion. Nature 388, 593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lonart G., Schoch S., Kaeser P. S., Larkin C. J., Südhof T. C., Linden D. J. (2003) Phosphorylation of RIM1alpha by PKA triggers presynaptic long-term potentiation at cerebellar parallel fiber synapses. Cell 115, 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simsek-Duran F., Linden D. J., Lonart G. (2004) Adapter protein 14-3-3 is required for a presynaptic form of LTP in the cerebellum. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1296–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chheda M. G., Ashery U., Thakur P., Rettig J., Sheng Z. H. (2001) Phosphorylation of Snapin by PKA modulates its interaction with the SNARE complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madison D. V., Nicoll R. A. (1982) Noradrenaline blocks accommodation of pyramidal cell discharge in the hippocampus. Nature 299, 636–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haas H. L., Konnerth A. (1983) Histamine and noradrenaline decrease calcium-activated potassium conductance in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature 302, 432–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy B. J., Rossie S., De Jongh K. S., Catterall W. A. (1993) Identification of the sites of selective phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the rat brain Na+ channel α subunit by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphoprotein phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 27355–27362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen T. C., Law B., Kondratyuk T., Rossie S. (1995) Identification of soluble protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate voltage-sensitive sodium channels in rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7750–7756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang C. C., Hsu K. S., Gean P. W. (1996) Isoproterenol potentiates synaptic transmission primarily by enhancing presynaptic calcium influx via P- and/or Q-type calcium channels in the rat amygdala. J. Neurosci. 16, 1026–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hell J. W., Yokoyama C. T., Breeze L. J., Chavkin C., Catterall W. A. (1995) Phosphorylation of presynaptic and postsynaptic calcium channels by cAMP-dependent protein kinase in hippocampal neurons. EMBO J. 14, 3036–3044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bos J. L. (2006) Epac proteins. Multipurpose cAMP targets. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kawasaki H., Springett G. M., Mochizuki N., Toki S., Nakaya M., Matsuda M., Housman D. E., Graybiel A. M. (1998) A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science 282, 2275–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Branham M. T., Bustos M. A., De Blas G. A., Rehmann H., Zarelli V. E., Treviño C. L., Darszon A., Mayorga L. S., Tomes C. N. (2009) Epac activates the small G proteins Rap1 and Rab3A to achieve exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24825–24839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang C. L., Katoh M., Shibasaki T., Minami K., Sunaga Y., Takahashi H., Yokoi N., Iwasaki M., Miki T., Seino S. (2009) The cAMP sensor Epac2 is a direct target of antidiabetic sulfonylurea drugs. Science 325, 607–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dzhura I., Chepurny O. G., Leech C. A., Roe M. W., Dzhura E., Xu X., Lu Y., Schwede F., Genieser H. G., Smrcka A. V., Holz G. G. (2011) Phospholipase C-ϵ links Epac2 activation to the potentiation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from mouse islets of Langerhans. Islets 3, 121–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozaki N., Shibasaki T., Kashima Y., Miki T., Takahashi K., Ueno H., Sunaga Y., Yano H., Matsuura Y., Iwanaga T., Takai Y., Seino S. (2000) cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt M., Evellin S., Weernink P. A., von Dorp F., Rehmann H., Lomasney J. W., Jakobs K. H. (2001) A new phospholipase-C-calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic AMP and a Rap GTPase. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1020–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sadana R., Dessauer C. W. (2009) Physiological roles for G protein-regulated adenylyl cyclase isoforms. Insights from knockout and overexpression studies. Neurosignals 17, 5–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ji X. H., Cao X. H., Zhang C. L., Feng Z. J., Zhang X. H., Ma L., Li B. M. (2008) Pre- and postsynaptic β-adrenergic activation enhances excitatory synaptic transmission in layer V/VI pyramidal neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex of rats. Cereb. Cortex 18, 1506–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kobayashi M., Kojima M., Koyanagi Y., Adachi K., Imamura K., Koshikawa N. (2009) Presynaptic and postsynaptic modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission by activation of α1- and β-adrenoceptors in layer V pyramidal neurons of rat cerebral cortex. Synapse 63, 269–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Millán C., Luján R., Shigemoto R., Sánchez-Prieto J. (2002) The inhibition of glutamate release by metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 affects both [Ca2+]c and cAMP. Evidence for a strong reduction of Ca2+ entry in single nerve terminals. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14092–14101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herrero I., Castro E., Miras-Portugal M. T., Sánchez-Prieto J. (1991) Glutamate exocytosis evoked by 4-aminopyridine is inhibited by free fatty acids released from rat cerebrocortical synaptosomes. Neurosci. Lett. 126, 41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trinquet E., Fink M., Bazin H., Grillet F., Maurin F., Bourrier E., Ansanay H., Leroy C., Michaud A., Durroux T., Maurel D., Malhaire F., Goudet C., Pin J. P., Naval M., Hernout O., Chrétien F., Chapleur Y., Mathis G. (2006) d-myo-inositol 1-phosphate as a surrogate of d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate to monitor G protein-coupled receptor activation. Anal. Biochem. 358, 126–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lujan R., Nusser Z., Roberts J. D., Shigemoto R., Somogyi P. (1996) Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 1488–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhong N., Zucker R. S. (2005) cAMP acts on exchange protein activated by cAMP/cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange protein to regulate transmitter release at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 25, 208–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brose N., Rosenmund C. (2002) Move over protein kinase C, you've got company. Alternative cellular effectors of diacylglycerol and phorbol esters. J. Cell Sci. 115, 4399–4411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodríguez-Castañeda F., Maestre-Martínez M., Coudevylle N., Dimova K., Junge H., Lipstein N., Lee D., Becker S., Brose N., Jahn O., Carlomagno T., Griesinger C. (2010) Modular architecture of Munc13/calmodulin complexes. Dual regulation by Ca2+ and possible function in short-term synaptic plasticity. EMBO J. 29, 680–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Betz A., Ashery U., Rickmann M., Augustin I., Neher E., Südhof T. C., Rettig J., Brose N. (1998) Munc13-1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron 21, 123–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]