Abstract

Motility disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract encompass a wide range of different diseases. Esophageal achalasia and functional dyspepsia are representative disorders of impaired motility of the esophagus and stomach, respectively. In spite of their variable prevalence, what both diseases have in common is poor knowledge of their etiology and pathophysiology. There is some evidence showing that there is a genetic predisposition towards these diseases, especially for achalasia. Many authors have investigated the possible genes involved, stressing the autoimmune or the neurological hypothesis, but there is very little data available. Similarly, studies supporting a post-infective etiology, based on an altered immune response in susceptible individuals, need to be validated. Further association studies can help to explain this complex picture and find new therapeutic targets. The aim of this review is to summarize current knowledge of genetics in motility disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, addressing how genetics contributes to the development of achalasia and functional dyspepsia respectively.

Keywords: Achalasia, Functional dyspepsia, Genetic predisposition, Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, Motility disorder

Core tip: Achalasia, functional dyspepsia and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis represent the main motility disorders of upper gastrointestinal tract. All these diseases have a less known pathophysiology and a presumable genetic predisposition in common. This review outlines the current knowledge on genes involved in the onset of these pathologies in order to promote further association studies which can help to explain this complex picture and find new therapeutic targets.

INTRODUCTION

Digestive motility is a highly coordinated process which enables mixing, absorption and propulsion of the ingesta through the gastrointestinal tract up to expulsion of residues. This function depends on a finely balanced integration between smooth muscle contractility and the related pacemaker activity evoked by the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) that are finely regulated by intrinsic and extrinsic innervations [i.e., enteric nervous system (ENS) and sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, respectively][1,2]. A disturbed digestive motility can occur as a result of a variety of abnormalities affecting each of these elements (alone or in combination), with consequent altered physiology of gut peristalsis and symptom generation.

The symptom complex is site specific and depends on the gastrointestinal tract involved. Thus, patients with disturbed esophageal motility may complain of dysphagia, regurgitation or chest pain, whereas patients with gastric dysmotility may report symptoms of nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, early satiety or epigastric pain. Esophageal achalasia and functional dyspepsia are the most representative motility disorders of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with the first rare and well characterized and the latter highly prevalent and less defined.

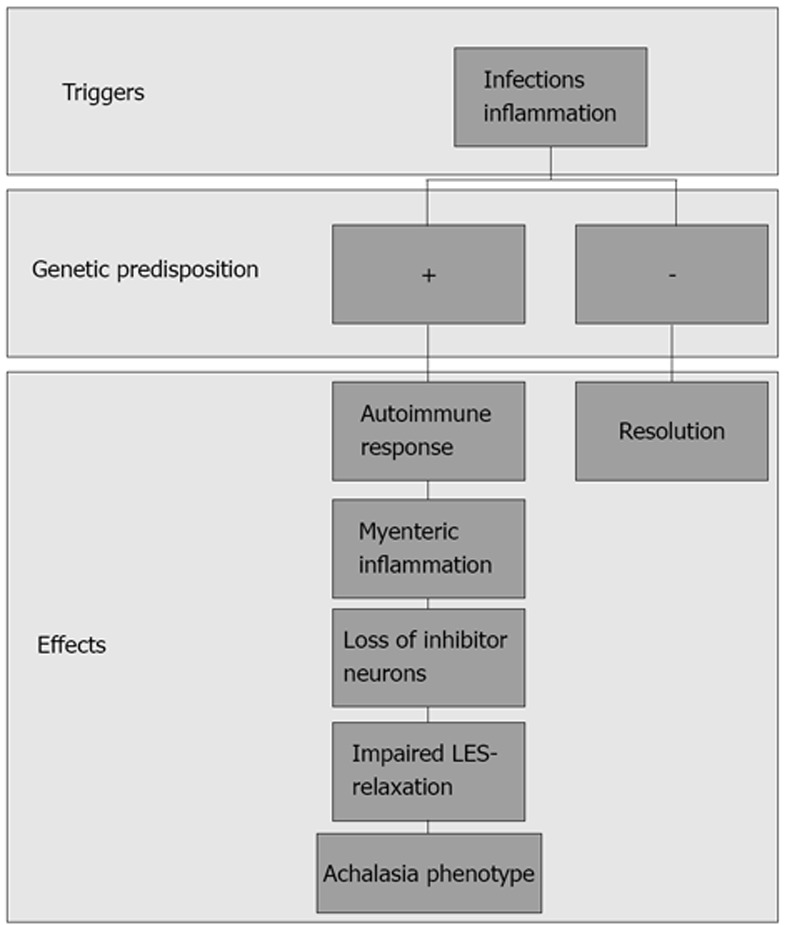

Like the majority of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), they are characterized by the persistence of symptoms in the absence of reliable biological markers. As for other complex diseases, the pathophysiology of impaired upper GI tract motility diseases is supposed to be multifactorial, with triggering external factors that are able to generate the gastrointestinal dysfunction in individuals who are more or less genetically predisposed (Figure 1). The idea that an individual genotype may contribute to the development of FGIDs is suggested by clinical observations and prospective studies indicating that there is clustering of FGIDs within families[3,4] and an increased concordance in monozygotic twins[5-7]. The most commonly used approach in functional dyspepsia (FD) to date has been to search for correlations of a candidate gene polymorphism with the symptom based phenotype. More recently, a few studies have aimed to identify correlations between gene polymorphism and biological intermediate phenotypes, such as impaired motility.

Figure 1.

Supposed pathophysiology of achalasia: triggering external factors are able to induce a loss of inhibitor neurons in individuals genetically predisposed, causing an impaired lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on the genetic contribution to upper GI motor disorders. We evaluate the most recent literature on the genetic epidemiology of representative motility disorders of the upper GI tract (UGT). We describe the putative genetic contributions that have been addressed and the potential association with single mechanisms, such as receptors, transporters and translation, or transduction mechanisms involved in the disturbed motility of the esophagus, stomach and pylorus, respectively impaired in esophageal achalasia, functional dyspepsia and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Each of the diseases can be considered paradigmatic because of the following: (1) hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is characteristic of infants and there is significant evidence about the role of genetic factors; (2) isolated idiopathic achalasia can be considered the prototype of defective esophageal motility in adults and the role of genetic factors is emerging as a major challenge to explain the disease; and (3) functional dyspepsia cannot be paradigmatically considered a primary gastric motor disorder, but is characterized by a significant association between impaired gastric motility and symptoms to which genetic factors contribute.

IMPAIRED MOTILITY OF THE ESOPHAGUS

Achalasia

Idiopathic achalasia is the best recognized primary motor disorder of the esophagus. It is characterized by incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LOS) and absence of peristalsis that causes bolus impaction and generation of symptoms like dysphagia, regurgitation and chest pain[8]. Although the pathogenesis of achalasia is still largely unknown, it is now clear that a major issue is the loss of neurons in the esophageal myenteric plexus. We know that neurons gradually disappear in the lower part of the esophagus of achalasia patients. In most cases, this process is the result of a localized infiltration of immune cells, determining an inflammatory-based neurodegeneration[9,10]. Interestingly, this process is prevalent for inhibitory neurons containing nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptides (VIP) and accounts for the loss of inhibitory inputs, with consequent abnormal esophageal function[11-13]. Notwithstanding this histological background, we do not know the precise pathogenic mechanism of achalasia; consequently, hereditary, degenerative, autoimmune and infectious factors have all been claimed to be possible causes of the disease.

A certain degree of genetic influence in achalasia is suggested by the familial occurrence and twin concordance. However, a systematic analysis of the literature revealed that twin concordance was significant but still inconclusive[6]. On the other hand, the only family study of achalasia conducted to date is biased by the small sample size and because the diagnosis of achalasia was based on a self-reported questionnaire[14]. In addition, achalasia may present as part of a genetic syndrome or in association with isolated abnormalities or diseases[15]. An achalasia phenotype is indeed present in well characterized genetic syndromes, like Down[16] and Allgrove syndromes[17], the familial visceral neuropathy[18] and the achalasia microcephaly syndrome[19]. In many of the above mentioned syndromes, achalasia does occur in the majority of the patients, but it generally presents in infancy.

Although these findings indicate that genetic factors are involved in the development of an achalasia phenotype, they do not provide insights into the pathogenesis of the sporadic form of achalasia, which affects the vast majority of patients and presents with adult-onset achalasia. As for other complex diseases, it is likely that the etiology of this form of achalasia is multifactorial, i.e., a combination of the cumulative effect of variants in various risk genes and environmental factors leads to the disorder. The idea of an infectious origin of achalasia was first suggested by the evidence of viruses or signs of viral infection in the esophageal tissues of achalasia patients[20-22], but the possibility that the presence of viruses could be sufficient per se to explain the disease was ruled out by other observations[23]. More recently, the concept that achalasia could be the result of an immune mediated inflammatory disorder induced by a virus has been strongly repurposed[24]. Facco et al[24] demonstrated that HSV-1 or HSV-like antigens were responsible for a significant activation of CD3+T cells infiltrating the LES in achalasia patients, likely resulting in an immune-mediated destruction of the myenteric neurons of the LOS. The reasons whereby this process occurs only in esophageal tissues of achalasia patients are unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that some genetic influence may affect the disease phenotype, making some individuals more susceptible to the disease. In addition and most interestingly, several evidences strongly support the idea that genes encoding for proteins involved in the immune response are likely candidates in achalasia.

A significant association between HLA DR or DQ, especially DQA1 *0103 and DQB1 *0603, and achalasia has been indeed described[25-27]. The increased risk for the development of achalasia in individuals with specific polymorphisms of genes involved in the immune response was also supported by the finding that the polymorphism C1858T of phosphatase N22 (PTPN22 gene, chromosome 1), which is a down-regulator of T-cell activation, is significantly associated with achalasia in Spanish women[28]. The same researchers have also demonstrated that the GCC haplotype of IL-10 gene promoter is a protective factor for achalasia. This specific polymorphism enhances the release of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, resulting in a downregulation of immune response[29]. In a similar manner, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the IL 23 receptor (G381A), which regulates T cell differentiation, appears to be protective against achalasia. De León et al[30] reported that the coding variant 381Gln of IL-23R was significantly more common in patients with achalasia compared with healthy controls.

This evidence sustains the role of both genetic predisposition and immune alteration in the pathogenesis of idiopathic achalasia. All data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of genetic association studies in achalasia

| Protein (gene) | Polymorphism | Finding | Ref. |

| PTPN22 | C1858T | Risk factor | [28] |

| IL-10 | GCC | Protective | [29] |

| IL-23R | G381A | Protective | [30] |

| iNOS | iNOS22*A/A | No association | [35] |

| eNOS | eNOS*4°4° | No association | [35] |

| iNOS | (CCTTT) n > 12 | Risk factor | [36] |

| cKit | Rs6554199 | Risk factor | [37] |

| VIPR type 1 | Rs437876 and rs896 | Risk factor | [38] |

iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL: Interleukin; PTPN22: Polymorphism C1858T of phosphatase N22.

Contribution of genes with a dual effect on motility and immunity

A disturbed inhibitory neurotransmission is a trademark of achalasia[11]. In keeping with this, several studies have addressed the role of NO and VIP that are involved in both defense against infections and inhibitory neurotransmission and may represent ideal candidates to explain the spread of inflammation and inhibitory nerve degeneration[12,13,19,31-33].

Nitric oxide is produced by three different forms of NO synthases: neuronal (nNOS), inducible (iNOS) and endothelial (eNOS). As NO production is genetically regulated, Mearin et al[34] firstly investigated whether SNP in the different NOS genes were respectively involved in the susceptibility to suffer from achalasia. Although a trend toward a higher prevalence of genotypes iNOS22?*A/A and eNOS*4a4a in patients than in controls was observed, the authors failed to find a significant association between NOS gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to achalasia. Although the simplest conclusion was that NO is not involved in the pathogenesis of achalasia, this study is biased by the small sample size and by the fact that the SNPs analyzed do not play a major role in gene expression. The lack of any association between the same SNP in the iNOS was also confirmed by a Spanish group in a larger population of achalasia patients, further suggesting that these specific polymorphisms play a minor role in the functional expression of the iNOS gene[35]. More recently, our group showed a significant association between the pentanucleotide (CCTTT) polymorphism in the iNOS gene promoter and achalasia. Since in vitro data showed that the iNOS promoter activity increases in parallel with the repeat number of (CCTTT)n, we concluded that individuals carrying longer forms have an increased risk of achalasia by higher nitric oxide production.

Moreover, growing evidence suggests that esophageal interstitial cells of Cajal, a group of specialized cells that constitutively expresses c-kit and contribute to nitrergic neurotransmission, may be involved in the pathogenesis of achalasia. Alahdab et al[36] have indeed shown that the rs6554199, but not rs2237025, c-kit polymorphism is significantly prevalent in achalasia patients in a Turkish population. Importantly, alterations in ICC have already been reported in other congenital diseases with abnormal peristalsis, emphasizing the key role of these cells in the regulation of GI motor function.

The implication of VIP in the pathogenesis of achalasia was also recently reported[37]. Two different SNPs, rs437876 and rs896, in the VIP-receptor type 1 gene were found to be significantly associated with the late onset achalasia. Interestingly, the authors suggest that this was probably related to a genetically based abnormal VIP-R1 signaling that may protect individuals carrying the specific genotype by delaying the immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Although these data need to be replicated, they are extremely interesting because they may suggest that early and late onset forms of idiopathic achalasia are genetically distinct disorders[38] (Table 1).

IMPAIRED MOTILITY OF THE STOMACH

FD

FD is defined by the presence of persistent symptoms in the upper part of the abdomen in the absence of organic or metabolic pathology[39]. On the basis of the Rome III criteria, patients who suffer from functional dyspepsia in the absence of any organic disease are categorized as having postprandial distress syndrome or epigastric pain syndrome[40].

In spite of this, the pathogenesis of FD is still largely unknown and, although delayed gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity have been all claimed as major underlying mechanisms, it is supposed to be a multifactorial disease[39].

The classic assumption in studies addressing the association between genetic factors and a single or a cluster of diseases postulates that a specific functional gene polymorphism that results in altered protein function may play a role in disease pathophysiology[41]. This paradigm that implies a clear correlation between impaired physiological function and symptom generation, however, cannot be applied to FD whose pathophysiology is complex and not necessarily associated with specific symptoms. Since functional dyspepsia is one of the most prevalent FGIDs, a certain genetic influence is suggested by both symptom familial clustering and twin studies reported for FD and IBS[3]. So far, most of the studies conducted were designed to search for correlations of a candidate gene polymorphism with the symptom-based phenotype of FD. The candidate genes that have been studied for possible associations with functional dyspepsia are summarized in Table 1.

In a subset of dyspepsia patients, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, even in the absence of ulceration or erosion in gastroduodenal mucosa, has been proposed to play a role in generation of symptoms. A Japanese group found an association between TLR-2 -196 to -174 allele with a lower risk for developing FD in Helicobacter pylori positive subjects. Since the same group had previously demonstrated that the TLR-2 -196 to -174 increases the severity of H. pylori-induced inflammation, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the TLR-2 genotype influences the onset of dyspeptic symptoms modulating the degree of inflammatory response[42].

Serotonin (5-HT) is a key signaling molecule affecting upper GI motor and sensory functions[43] and thus genes of the serotonergic system are critical candidates in assessing the role of genetic determinants in FD. The action of 5-HT is terminated by the 5-HT transporter (serotonin transporter, SERT) mediated uptake, thereby determining 5-HT availability at the receptor level. A single nucleotide insertion/deletion in the SERT gene, by creating a long (L) and short (S) allelic variant, results in reduced SERT expression and 5-HT uptake[44]. Although the SS genotype of the SERT promoter polymorphism has been reported to be associated with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), two different studies from the United States[45] and Europe[46] failed to find any significant association between such polymorphisms and FD. Similarly, association studies between SNPs of the 5-HT3, 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in FD patients failed to yield significant association[45,46]. Although both studies were conducted on small populations of patients, the results suggest that the serotoninergic pathway plays a minor role in the pathophysiology or, at least in part, in the generation of dyspeptic symptoms.

Another genetic association reported in functional dyspepsia is the link to GNβ3[47]. G-proteins mediate the response to the release of 5-HT and several other neurotransmitters modulating gastroduodenal sensory and motor function.

A common polymorphism of GNβ3 gene has been described and is associated with different genotypes that are predictive of an enhanced G-protein activation. A significant association between different GNβ3 polymorphisms and both uninvestigated and investigated dyspepsia has been reported in different studies from the United States[45], Europe[46,47] and Asia[48,49]. Although the sample sizes remain relatively small in all of these studies, which may account for some of the variability in the associations detected, it is of note that the different classifications of dyspepsia also contribute to the diverse distribution of polymorphisms. In fact, while homozygous GNB3 825T allele was found to influence the susceptibility to EPS-like dyspepsia in a Japanese population of dyspeptics[49], in a report from the United States, the same polymorphism was associated with postprandial dyspeptic symptoms and lower fasting gastric volumes[45]. Other studies failed to identify single genetic factors as a predominant factor in the pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia and symptom generation. As sympathetic adrenergic dysfunctions may affect both gastric sensitivity, Camilleri et al[45] analyzed the role of presynaptic inhibitory α2A and α2B adrenoceptors polymorphism, but they failed to find any significant association with dyspepsia symptoms. The same group also failed to find any significant association between the genetic variation in the endocannabinoid metabolism (i.e., a SNP in the human fatty acid amide hydrolase gene-C385A-) and both impaired fundus accommodation and delayed gastric emptying in a small subgroup of dyspepsia patients[50]. Conversely, in a recent report, the involvement of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) was investigated in a small population of Japanese dyspeptic patients. The authors found that in a population of 109 dyspeptics, individuals carrying the G315C polymorphism, known to affect the TRPV1 gene and to alter its protein level, were at lower risk for both epigastric pain and postprandial distress syndrome. In addition, the authors showed that dyspeptics with that specific polymorphism had a baseline and cold water induced symptom severity[47]. Although this finding needs to be reproduced in different ethnic populations and validated on a large sample, it is of note that TRPV1 pathways may be ideal candidates as they are involved in nociception and in acid sensitivity, with the latter being claimed to have a role in the generation of dyspepsia symptoms. On the same line, the same group have found a significant association between a polymorphism of the tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-r) sodium channel Na (V) 1.8, a channel expressed by C-fibers and involved in nociception, and functional dyspepsia. Indeed, the SCN10A 3218 CC variant, which determines a lower activity of this Na (V)-channel, was significantly associated with a decreased risk for the development of FD[52] (all data are summarized in Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of genetic association studies in functional dyspepsia

| Protein (gene) | Polymorphism | Finding | Ref. |

| TLR-2 | (192-174)del | Protective for Helicobacter pylori-infected patients | [43] |

| SERT | SS variant | No association | [45] |

| 5-HT1A | -Pro16Leu | No association | [46,47] |

| 5-HT2A | -1438 G/A | No association | [46,47] |

| HTR3A | C178T | No association | [46,47] |

| GNB3 | C825T | Risk factor | [48-50] |

| CT and TT carriers | |||

| GNB3 | C825T | Risk factor for PDS | [48-50] |

| CC and TT carriers | |||

| GNB3 | C825T | Risk factor | [48-50] |

| CC carriers | |||

| GNB3 | C825T | Risk factor for EPS | [50] |

| TT carriers | |||

| Presynaptic inhibitory α2A and α2C adrenoceptor | -1291 C>G (α2A) and -del 1322-325 (α2A) | No association | [46] |

| Fatty acid amide hydrolase | C385A | No association | [51] |

| TRPV1 | G315C | Risk factor | [52] |

| Na (V) 1.8 | SCN10A | Protective | [53] |

| 3218CC |

PDS: Post discharge surveillance; EPS: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TRPV: Transient receptor potential vanilloid.

Post-infectious dyspepsia

By summarizing what we have described above, we can say that although it is unlikely that a single genetic factor causes FD, it is more likely that a genetic factor (or factors) modulates the risk of developing the abnormalities after exposure to one or more specific environmental factors[53]. This paradigm is well supported by the hypothesis of a post-infectious origin of dyspepsia. Indeed, it is now evident that in a subgroup of patients with functional dyspepsia, acute GI infections may precipitate symptoms. Data from the literature indicate that in presumed post-infectious dyspepsia patients there is an increased prevalence of impaired gastric accommodation to the meal that is likely dependent on inflammatory-induced impaired nitrergic innervation of the gastric wall[54]. However, only one study systematically addressed the genetic contribution to post-infectious dyspepsia and the data presented are quite controversial since a significant association between macrophage migration inhibitory factor-173C and IL17F-7488T polymorphisms was only observed in the subgroup of patients with symptoms suggestive of EPS-like dyspepsia[55]. Indirect evidence for a role of inflammatory products gene in the genesis of FD is also suggested by a Japanese study in which a significant association between a COX1 polymorphism and EPS-like symptoms was observed in a subgroup of dyspeptic female patients[56]. However, a very recent study investigating the role of a polymorphism in the receptor for neuropeptide S receptor gene (NPSR1) that is involved in inflammation, anxiety and nociception failed to reveal any significant association with FD[57] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of genetic association studies in post-infectious dyspepsia

| Protein (gene) | Polymorphism | Finding | Ref. |

| MIF | -173C | Risk factor for EPS | [56] |

| IL17 | -7488T | Risk factor for EPS | [56] |

| COX-1 | T1676C | Risk factor for EPS | [57] |

| NPS-R | rs2609234, rs6972158, and rs1379928 | No association | [58] |

IL: Interleukin; COX-1: Cyclooxygenase-1; EPS: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis; MIF: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

Isolated HPS is a common condition characterized by the hypertrophy of the muscle surrounding the pylorus, with impaired sphincter relaxation and consequent gastric outlet obstruction which causes severe non-bilious vomiting. The etiology of this disease is still largely unknown; however, epidemiological studies indicate that genetic factors play an important role in the pathophysiology of this entity[58]. Krogh et al[59] have shown a 200-fold increased risk of HPS in monozygotic twins and a 20-fold increased risk among siblings of affected children. In particular, different studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of HPS in offspring of an affected mother compared with offspring of an affected father, suggesting a major role of maternal factors; however, this evidence was not confirmed in further studies[60]. In addition, HPS is associated with several well-defined genetic syndromes, sustaining the hypothesis that genetic factors are largely involved in the pathogenesis of this disease[58].

A reduced expression of NOS1 was demonstrated at the mRNA level in pyloric tissue of patients with HPS, suggesting a pathogenic role of nNOS in this disease. For this reason, several researchers have analyzed the gene of NOS1; however, only a Chinese group found a linkage between HPS and NOS1a on chromosome 12q[61], but this result was not confirmed by another study[62]. Moreover, the analysis of the complete coding region of NOS1 in patients and controls revealed no significant difference, confirming that the impaired nNOS function in the pylorus of these patients is not related to a direct mutation of the gene encoding for NOS1[63].

Several studies have demonstrated a linkage between HPS and different loci in affected patients of the same family, but larger studies on additional families were usually unsuccessful. A Chinese group described a linkage of a SNPs of chromosome 16 (16p12-p13) in 10 affected members of the same family, but this association was not observed in 10 additional families[64]. Moreover, the major candidate genes of this region encoding for MYH11 and GRIN2A, proteins involved in smooth muscle relaxation, have not shown mutations[64]. In members of the same family, Everett et al[65] found an association with SLC7A5 (16q24), a gene which influences NO activity; however, they failed to confirm these data on additional 14 families. In a genome-wide linkage study, the same group demonstrated an association between HPS and some loci on chromosome 11q14-q22 and Xq23, both encoding for protein involved in the functioning of ion channels (TRPC5 and TRPC6) in 81 families with 206 affected members[66,67]; however, a subsequent Chinese study failed to replicate the association with TRPC6[68].

Finally, a Danish group in a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) on 1001 individuals affected by HPS and 2401 healthy controls demonstrated an association between HPS and three SNPs of MBNL1 and NKX 2-5, genes involved in the splicing and transcription processes[69], but it was the first GWAS and these results could explain only a very small proportion of HPS cases (all reviewed associations are summarized in Table 4).

Table 4.

Overview of genetic association studies in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

| Protein (gene) | Chromosome | Finding | Ref. |

| NOS1 | 12q | Association | [62,63] |

| MYH11-GRIN2A | 16p12-p13 | Association | [65] |

| SLC7A5 | 16q24 | Association | [66] |

| TRPC5 and TRPC6 | 11q14-q22 and Xq23 | Association | [67-69] |

In conclusion, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a multifactorial disease and both genetic and environmental factors could contribute to the pathophysiology of this condition. Especially for the syndromic form of HPS, different mutations in different genes involved in different functions have been associated with the onset of this disease, but we are still far from a single unifying pathogenetic factor. Conversely, in the sporadic form of the disease, the contribution of the genetic background is even more scanty and complex and no clear triggering factors have been described yet, further sustaining the great heterogeneity of this disease.

CONCLUSION

Several association studies have established a genetic component in the genesis of motility disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, like esophageal achalasia, functional dyspepsia and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Although candidate gene studies have identified a few gene polymorphisms that may be correlated with these syndromes, small sample size, lack of reproducibility in large data sets, and the unreliability of the clinical phenotype represent a major limit to identify a unifying factor in the pathophysiology of these syndromes in any of the reported polymorphisms.

Whether the genetic contribution plays a crucial role in the generation of upper GI tract symptoms therefore deserves further studies. More specifically, the recruitment of large case-control samples appears to be mandatory in order to provide a powerful tool for the identification of risk genes, especially for diseases like achalasia and functional dyspepsia, in which a multifactorial inheritance is assumed. In this direction, genome-wide association studies will allow for the unbiased and systematic identification of risk genes and may represent the greatest challenge for all future studies of upper GI tract motility disorders.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Akiba Y, Lindberg G S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Goyal RK, Hirano I. The enteric nervous system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1106–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood JD. Neural and humoral regulation of gastrointestinal motility. In: Schuster MM, Crowell MD, Koch KL, editors. Gastrointestinal motility in health and disease. London: BC Decker; 2002. pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Familial association in adults with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:907–912. doi: 10.4065/75.9.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tryhus MR, Davis M, Griffith JK, Ablin DS, Gogel HK. Familial achalasia in two siblings: significance of possible hereditary role. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:292–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris-Yates A, Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Nandurkar S, Andrews G. Evidence of a genetic contribution to functional bowel disorder. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1311–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.440_j.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein DT, Knauer CM. Achalasia in monozygotic twins. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:636–640. doi: 10.1007/BF01297220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenbo T, Zaman MS, Chavez NF, Krueger R, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Concordance of IBS among monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Gastroenterol. 2001;120(suppl 1):A–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter JE. Oesophageal motility disorders. Lancet. 2001;358:823–828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Richter JE. Histopathologic features in esophagomyotomy specimens from patients with achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:648–654. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark SB, Rice TW, Tubbs RR, Richter JE, Goldblum JR. The nature of the myenteric infiltrate in achalasia: an immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1153–1158. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mearin F, Mourelle M, Guarner F, Salas A, Riveros-Moreno V, Moncada S, Malagelada JR. Patients with achalasia lack nitric oxide synthase in the gastro-oesophageal junction. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:724–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konturek JW, Thor P, Lukaszyk A, Gabryelewicz A, Konturek SJ, Domschke W. Endogenous nitric oxide in the control of esophageal motility in humans. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48:201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal RK, Rattan S, Said SI. VIP as a possible neurotransmitter of non-cholinergic non-adrenergic inhibitory neurones. Nature. 1980;288:378–380. doi: 10.1038/288378a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. A study of swallowing difficulties in first degree relatives of patients with achalasia. Thorax. 1985;40:391–393. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.5.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM. Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights? Hum Genet. 2010;128:353–364. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okawada M, Okazaki T, Yamataka A, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Down’s syndrome and esophageal achalasia: a rare but important clinical entity. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:997–1000. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allgrove J, Clayden GS, Grant DB, Macaulay JC. Familial glucocorticoid deficiency with achalasia of the cardia and deficient tear production. Lancet. 1978;1:1284–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett JL, McDonnell WM, Appelman HD, Dobbins WO. Familial visceral neuropathy with neuronal intranuclear inclusions: diagnosis by rectal biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:684–691. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90121-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalifa MM. Familial achalasia, microcephaly, and mental retardation. Case report and review of literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1988;27:509–512. doi: 10.1177/000992288802701009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Concha EG, Fernandez-Arquero M, Conejero L, Lazaro F, Mendoza JL, Sevilla MC, Diaz-Rubio M, Ruiz de Leon A. Presence of a protective allele for achalasia on the central region of the major histocompatibility complex. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:149–153. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.560206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones DB, Mayberry JF, Rhodes J, Munro J. Preliminary report of an association between measles virus and achalasia. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:655–657. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson CS, Martin BA, Atkinson M. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in the oesophageal myenteric plexus in achalasia. Gut. 1993;34:299–302. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birgisson S, Galinski MS, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Richter JE. Achalasia is not associated with measles or known herpes and human papilloma viruses. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:300–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1018805600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facco M, Brun P, Baesso I, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Berto A, Baldan N, Palù G, Semenzato G, Castagliuolo I, et al. T cells in the myenteric plexus of achalasia patients show a skewed TCR repertoire and react to HSV-1 antigens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1598–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De la Concha EG, Fernandez-Arquero M, Mendoza JL, Conejero L, Figueredo MA, Perez de la Serna J, Diaz-Rubio M, Ruiz de Leon A. Contribution of HLA class II genes to susceptibility in achalasia. Tissue Antigens. 1998;52:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verne GN, Hahn AB, Pineau BC, Hoffman BJ, Wojciechowski BW, Wu WC. Association of HLA-DR and -DQ alleles with idiopathic achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong RK, Maydonovitch CL, Metz SJ, Baker JR. Significant DQw1 association in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:349–352. doi: 10.1007/BF01536254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santiago JL, Martínez A, Benito MS, Ruiz de León A, Mendoza JL, Fernández-Arquero M, Figueredo MA, de la Concha EG, Urcelay E. Gender-specific association of the PTPN22 C1858T polymorphism with achalasia. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:867–870. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuñez C, García-González MA, Santiago JL, Benito MS, Mearín F, de la Concha EG, de la Serna JP, de León AR, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association of IL10 promoter polymorphisms with idiopathic achalasia. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:749–752. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de León AR, de la Serna JP, Santiago JL, Sevilla C, Fernández-Arquero M, de la Concha EG, Nuñez C, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association between idiopathic achalasia and IL23R gene. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:734–738, e218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tøttrup A, Svane D, Forman A. Nitric oxide mediating NANC inhibition in opossum lower esophageal sphincter. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:G385–G389. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.3.G385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croen KD. Evidence for antiviral effect of nitric oxide. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2446–2452. doi: 10.1172/JCI116479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delgado M, Pozo D, Ganea D. The significance of vasoactive intestinal peptide in immunomodulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:249–290. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mearin F, García-González MA, Strunk M, Zárate N, Malagelada JR, Lanas A. Association between achalasia and nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1979–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigo AG, Martínez A, de la Concha EG, Urcelay E, Ruiz de León A. Suggested association of NOS2A polymorphism in idiopathic achalasia: no evidence in a large case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1326–1327. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alahdab YO, Eren F, Giral A, Gunduz F, Kedrah AE, Atug O, Yilmaz Y, Kalayci O, Kalayci C. Preliminary evidence of an association between the functional c-kit rs6554199 polymorphism and achalasia in a Turkish population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paladini F, Cocco E, Cascino I, Belfiore F, Badiali D, Piretta L, Alghisi F, Anzini F, Fiorillo MT, Corazziari E, et al. Age-dependent association of idiopathic achalasia with vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 gene. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:597–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarnelli G. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on the pathogenesis of achalasia: an age-dependent paradigm? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:575–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1239–1255. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holtmann G, Liebregts T, Siffert W. Molecular basis of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tahara T, Shibata T, Wang F, Yamashita H, Hirata I, Arisawa T. Genetic Polymorphisms of Molecules Associated with Innate Immune Responses, TRL2 and MBL2 Genes in Japanese Subjects with Functional Dyspepsia. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;47:217–223. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tack J, Sarnelli G. Serotonergic modulation of visceral sensation: upper gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i77–i80. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camilleri M, Atanasova E, Carlson PJ, Ahmad U, Kim HJ, Viramontes BE, McKinzie S, Urrutia R. Serotonin-transporter polymorphism pharmacogenetics in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:425–432. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camilleri CE, Carlson PJ, Camilleri M, Castillo EJ, Locke GR, Geno DM, Stephens DA, Zinsmeister AR, Urrutia R. A study of candidate genotypes associated with dyspepsia in a U.S. community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:581–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Lelyveld N, Linde JT, Schipper M, Samsom M. Candidate genotypes associated with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holtmann G, Siffert W, Haag S, Mueller N, Langkafel M, Senf W, Zotz R, Talley NJ. G-protein beta 3 subunit 825 CC genotype is associated with unexplained (functional) dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:971–979. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, Wang F, Nakamura M, Sakata M, Hirata I, Nakano H. Homozygous 825T allele of the GNB3 protein influences the susceptibility of Japanese to dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:642–646. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshima T, Nakajima S, Yokoyama T, Toyoshima F, Sakurai J, Tanaka J, Tomita T, Kim Y, Hori K, Matsumoto T, et al. The G-protein beta3 subunit 825 TT genotype is associated with epigastric pain syndrome-like dyspepsia. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camilleri M, Carlson P, McKinzie S, Grudell A, Busciglio I, Burton D, Baxter K, Ryks M, Zinsmeister AR. Genetic variation in endocannabinoid metabolism, gastrointestinal motility, and sensation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G13–G19. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00371.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tahara T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Yamashita H, Yoshioka D, Hirata I, Arisawa T. Homozygous TRPV1 315C influences the susceptibility to functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e1–e7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b5745e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shiroeda H, Minato T, Matsue Y, Saito T, Fukuyama T, Otsuka T, Fukumura A, Nakamura M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of SCN10A are associated with functional dyspepsia in Japanese subjects. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holtmann G, Talley NJ. Hypothesis driven research and molecular mechanisms in functional dyspepsia: the beginning of a beautiful friendship in research and practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:593–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tack J, Demedts I, Dehondt G, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Zandecki M, Janssens J. Clinical and pathophysiological characteristics of acute-onset functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1738–1747. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Arima Y, Okubo M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of molecules associated with inflammation and immune response in Japanese subjects with functional dyspepsia. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Arima Y, Okubo M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) are associated with functional dyspepsia in Japanese women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1039–1043. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camilleri M, Carlson P, Zinsmeister AR, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, Burton D, Zucchelli M, D’Amato M. Neuropeptide S receptor induces neuropeptide expression and associates with intermediate phenotypes of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:98–107. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peeters B, Benninga MA, Hennekam RC. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis--genetics and syndromes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:646–660. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krogh C, Fischer TK, Skotte L, Biggar RJ, Øyen N, Skytthe A, Goertz S, Christensen K, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Familial aggregation and heritability of pyloric stenosis. JAMA. 2010;303:2393–2399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell LE, Risch N. The genetics of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. A reanalysis. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:1203–1211. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160350077012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung E, Curtis D, Chen G, Marsden PA, Twells R, Xu W, Gardiner M. Genetic evidence for the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene (NOS1) as a susceptibility locus for infantile pyloric stenosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:363–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Söderhäll C, Nordenskjöld A. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase, nNOS, is not linked to infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in three families. Clin Genet. 1998;53:421–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serra A, Schuchardt K, Genuneit J, Leriche C, Fitze G. Genomic variants in the coding region of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1903–1908. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Capon F, Reece A, Ravindrarajah R, Chung E. Linkage of monogenic infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis to chromosome 16p12-p13 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:378–382. doi: 10.1086/505952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Everett KV, Capon F, Georgoula C, Chioza BA, Reece A, Jaswon M, Pierro A, Puri P, Gardiner RM, Chung EM. Linkage of monogenic infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis to chromosome 16q24. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Everett KV, Chioza BA, Georgoula C, Reece A, Capon F, Parker KA, Cord-Udy C, McKeigue P, Mitton S, Pierro A, et al. Genome-wide high-density SNP-based linkage analysis of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis identifies loci on chromosomes 11q14-q22 and Xq23. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Everett KV, Chioza BA, Georgoula C, Reece A, Gardiner RM, Chung EM. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: evaluation of three positional candidate genes, TRPC1, TRPC5 and TRPC6, by association analysis and re-sequencing. Hum Genet. 2009;126:819–831. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0735-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ju JJ, Gao H, Li H, Lu Y, Wang LL, Yuan ZW. No association between the SNPs (rs56134796; rs3824934; rs41302375) in the TRPC6 gene promoter and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Chinese people. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1267–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2961-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feenstra B, Geller F, Krogh C, Hollegaard MV, Gørtz S, Boyd HA, Murray JC, Hougaard DM, Melbye M. Common variants near MBNL1 and NKX2-5 are associated with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:334–337. doi: 10.1038/ng.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]