Abstract

Aerodigestive cancer, like esophageal cancer or head and neck cancer, is well known to have a poor prognosis. It is often diagnosed in the late stages, with dysphagia being the major symptom. Insufficient nutrition and lack of stimulation of the intestinal mucosa may worsen immune compromise due to toxic side effects. A poor nutritional status is a significant prognostic factor for increased mortality. Therefore, it is most important to optimize enteral nutrition in patients with aerodigestive cancer before and during treatment, as well as during palliative treatment. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) may be useful for nutritional support. However, PEG tube placement is limited by digestive tract stenosis and is an invasive endoscopic procedure with a risk of complications. There are three PEG techniques. The pull/push and introducer methods have been established as standard techniques for PEG tube placement. The modified introducer method, namely the direct method, allows for direct placement of a larger button-bumper-type catheter device. PEG tube placement using the introducer method or the direct method may be a much safer alternative than the pull/push method. PEG may be recommended in patients with aerodigestive cancer because of the improved complication rate.

Keywords: Aerodigestive cancer, Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, Direct method, Introducer method, Pull/push method, Complications

Core tip: Aerodigestive cancer is well known to have a poor prognosis and is often diagnosed in the late stages with dysphagia. Insufficient nutrition and lack of stimulation of the intestinal mucosa may worsen immune compromise. Therefore, it is most important to optimize enteral nutrition before and during treatment, as well as during palliative treatment. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) may be useful for nutritional support. PEG tube placement using the introducer method or the direct method may be a much safer alternative than the pull/push method. PEG may be recommended in patients with aerodigestive cancer because of the improved complication rate.

INTRODUCTION

Tumors of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction or head and neck are some of the most malignant cancers with high mortality rates because many patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages[1]. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is one of the most distressing and debilitating symptoms. Dysphagia leads to nutritional compromise and deterioration of quality of life[2,3]. When the esophageal lumen becomes stenotic to less than 14 mm in diameter, dysphagia generally develops. It first becomes difficult to swallow solid food. Next, it becomes difficult to swallow semisolid food. Finally, fluids and even saliva are difficult to swallow[4]. Patients develop anorexia and significant weight loss secondary to the tumor effects and may present with varying degrees of malnutrition. A poor nutritional status is a significant prognostic factor for increased mortality[5].

Selection of therapy for aerodigestive cancer is dependent upon the tumor stage, location and histological type, and the physician’s experience and preference. Therapeutic options include surgical resection of the primary tumor, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Therapies are sometimes combined, such as chemotherapy plus surgery or chemotherapy and radiotherapy plus surgery. Many of these patients find that their initial dysphagia worsens during this treatment because of side effects such as esophagitis and oral mucositis. Moreover, insufficient nutrition and lack of stimulation of the intestinal mucosa may worsen immune compromise due to toxic side effects[6]. During these periods, it is most important to optimize enteral nutrition. Early enteral nutrition reduces the incidence of life-threatening surgical complications in patients who undergo esophagectomy or esophagogastrectomy for esophageal carcinoma[7-11]. Nutrition is administered through a transnasal feeding tube for short-term feeding when oral intake is not possible. When chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy are intended to be curative, they frequently compromise oral intake for a long period of time. Nasogastric tubes are easy to place but they are poorly tolerated for prolonged periods of feeding. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) may be one of the best options for nutritional support.

A majority of patients are destined to receive palliation only, which is associated with a severely impaired health-related quality of life. These patients require palliative treatment, including brachytherapy, chemotherapy and endoscopic palliation techniques, such as esophageal dilatation, intraluminal stents and laser therapy, to relieve progressive dysphagia[12,13]. The two most commonly used strategies for improving swallowing are stent insertion and radiation, including intraluminal brachytherapy. They allow for an almost normal oral intake. Unfortunately, some patients develop restenosis symptoms after palliative therapy and some develop severe treatment-related side effects such as mucositis from radiation therapy. Stent insertion is difficult in some patients with proximal esophageal cancers or head and neck cancers. For these patients, PEG or nasal tubes may be the best options for nutritional support.

PEG PROCEDURE

There are three PEG tube insertion methods. The pull/push and introducer methods have been established as standard techniques for PEG tube placement. In the pull/push method, the feeding tube is introduced through the mouth. In the introducer method, balloon-type catheter feeding tubes can be inserted directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall. The third method is the modified introducer method (i.e., direct method). The direct method allows for direct placement of a larger button-bumper-type catheter device. Use of the direct method is spreading in Japan, but it is not yet used worldwide[14]. Each method has advantages and disadvantages.

Pull/push method

The pull/push PEG technique is based on the standard Ponsky technique in which a guidewire is inserted through the abdominal wall under endoscopic guidance, grasped by a snare through a port on the endoscope, and subsequently advanced in a retrograde manner through the patient’s mouth. The remaining end exits the patient through the anterior abdominal wall. A 20-French Ross Flexiflo Inverta-PEG tube (Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH) is then secured to the transoral end of the patient’s mouth and abdominal wall by pulling the extra-abdominal end of the wire to advance the gastrostomy tube[15].

Introducer method

The introducer PEG technique is based on the Russell introducer method of PEG placement. After the endoscope is inserted and the PEG site is marked, four T-fasteners are placed before gastrostomy tube insertion to secure the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall. This prevents gastric wall displacement while inserting the gastrostomy tube. Using the Seldinger technique, a short guidewire is then passed transabdominally under endoscope visualization. Serial dilators are passed over the guidewire to create a stoma tract; the endoscope remains in place for visualization and verification of gastrostomy tube placement. An 18-French Ross Flexiflo gastrostomy tube (Abbott Laboratories) is then inserted or pushed over the guidewire, directly through the anterior abdominal wall[16].

Direct method

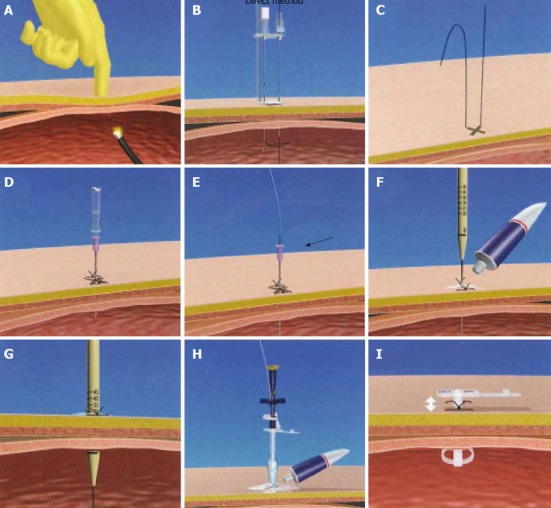

The direct method is a modified version of the introducer method (Direct Ideal PEG kit; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). After the stomach is secured to the anterior abdominal wall, the skin incision is dilated by passing a dilator percutaneously into the stomach over the guidewire as the same as introducer method. After the dilator is removed, a 24-French PEG tube is inserted using an obturator[14] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Direct method. A: The transilluminated area on the abdominal wall was pushed with a finger; B, C: The stomach was punctured using a double-lumen gastropexy device; D: A needle with an outer plastic sheath (18-French) was introduced into the stomach under endoscopic control; E: The needle was removed and the guidewire was replaced; F, G: The skin incision was dilated by passing a dilator percutaneously into the stomach over the guidewire under endoscopic visualization; H: After the dilator was removed, a 24-French percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube using an obturator was inserted over the guidewire; I: The tube was fixed to the abdominal wall.

OUTCOMES OF PEG

PEG in patients with aerodigestive cancer

PEG tube feeding is the preferred method with which to provide long-term tube feeding and its use is currently widespread. Many studies have examined the usefulness of PEG for aerodigestive cancer. A PEG tube was inserted in patients with oral intake difficulties for the purpose of nutrition support in all stages and locations, including patients who had undergone chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy with curative intent[17-22]. Chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy is frequently associated with mucositis, dysphagia, loss of taste and anorexia. Chemotherapy, chemoradiation therapy and hyperfractionated radiation therapy are usually associated with even more severe treatment-related side effects and greater impairment of swallowing function. These treatments are long-term. Therefore, during these periods, PEG tube insertion may be one of the best options for nutritional support if the complication and mortality rates of PEG are low. Nasogastric tubes are easy to place but they are poorly tolerated for prolonged periods of feeding because they are associated with frequent ulceration, esophageal reflux and general discomfort. PEG tubes are better tolerated but they must be used selectively in patients who can be predicted to have a long-term need for nutritional support[23].

There are more reports of patients with head and neck cancer than patients with esophageal cancer. One of the reasons is that in the operation planned in esophageal cancer patients, PEG may limit the reconstruction of the stomach after esophagectomy because of the adhesion of the stomach and the abdominal wall, or the possibility of the injury for the right gastroepiploic artery which is needed in the reconstruction of the stomach[17]. Another reason for this is that stent insertion and brachytherapy are the first-choice palliative treatments in patients with middle and low esophageal cancers in many institutions. In terms of nutritional support, the most important factor is maintenance of oral food intake, which should stabilize or even improve quality of life. Dysphagia improves more rapidly after stent placement[12,13] and long-term relief of dysphagia is better after brachytherapy[24,25]. Therefore, stent placement may be reserved for esophageal cancer patients with severe dysphagia in combination with a short life expectancy who need more rapid relief of dysphagia and for patients with persistent or recurrent tumor growth after brachytherapy[12,13]. When these modalities are technically not possible, nutritional support with a nasoenteric feeding tube or PEG tube should be considered to maintain adequate calorie intake. Grilo et al[22] suggest that PEG should be considered as a nutritional support method in patients with upper esophageal cancer that is unsuitable for esophageal stenting. For patients who suffer from restenosis symptoms after palliative therapy or who have proximal esophageal cancers or head and neck cancer, PEG may be one of the best options for nutritional support.

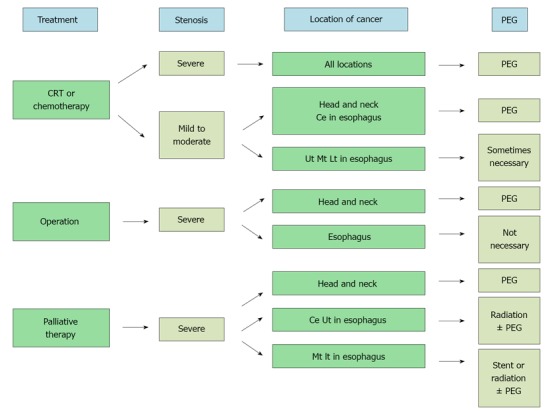

Thus, depending on the treatment, disease and the degree of stenosis, the following situations are indications for PEG. First, in aerodigestive cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy who are suffering from dysphagia, PEG is the first choice. Stenosis, even if not severe, and if lesions are located in the upper esophagus or head and neck, is an indication for PEG because difficult long-term oral intake is expected due to mucositis and esophagitis during the treatment. Next, in the operation planned for head and neck cancer patients, PEG is indicated because the stomach is not used for reconstruction. Lastly, in palliative treatment, patients with lesions of the upper esophagus or head and neck with the difficulty of a stent are indications for PEG. In addition, PEG will be indicated in patients in whom stenosis is severe even after palliative radiation therapy or a stent (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Algorithm of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy for aerodigestive cancer. CRT: Chemoradiation therapy; Ce: Cervical esophagus; Ut: Upper thoracic esophagus; Mt: Middle thoracic esophagus; Lt: Lower thoracic esophagus; PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

However, studies on this topic have weaknesses typical to retrospective studies. Nugent et al[26] and Locher et al[27] reported that there is insufficient evidence to determine the optimal method of enteral feeding for patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy and/or chemoradiotherapy. Larger studies of enteral feeding in patients with esophageal cancer are needed.

COMPLICATIONS

PEG tube placement is an invasive endoscopic procedure with a risk of complications. Minor complications resulting from PEG tube placement include cellulitis, ileus, peristomal leakage, extrusion, tube obstruction and gastric wall hematoma formation. Major complications include peritonitis, hemorrhage, airway aspiration, peristomal wound infection, buried bumper syndrome, tumor implantation and gastrocolic fistula[28,29] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of the pull, introducer and direct percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement methods

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Pull method | Bumper type device inside stomach prevents misplacement of catheter Large-bore catheters can be used immediately after placement | Catheter may be contaminated during passage through mouth/esophagus → Increased risk of wound infection and tumor implantation Endoscope must be inserted twice to confirm correct placement |

| Introducer method | Adherence to aseptic technique guarantees low risk of wound infection Endoscope must be inserted only once | Risk of bleeding and incorrect puncture with large trocar Only small-lumen catheters can be used immediately after placement Catheter size must be increased step by step High probability of catheter misplacement (if using balloon type) |

| Direct PEG Kit | Adherence to aseptic technique guarantees low risk of wound infection Endoscope must be inserted only once Small puncture needle and blunt dilator → small wound One-step insertion of bumper type device Large-bore catheters can be used immediately after placement | Risk of bleeding |

PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

The major complications of the standard pull/push method, which requires an esophageal lumen sufficient to pass a standard endoscope[30], include peristomal wound infections, presumably resulting from contamination of the gastrostomy catheter as it passes through the oral cavity[14,31], and tumor implantation at the PEG site[28,32] which are specific for pull/push method in the aerodigestive cancer patients. In the literature on patients with cancer, the overall complication and mortality rates of the pull/push method in patients with head and neck cancer are 10.9%-42.0% and 0%-5%, respectively[15,17,18,20-22,33-36].

An overall complication rate of 0%-11% and mortality rate of 0% have been reported with the introducer method[15,16,37,38] compared with the pull/push method in patients with aerodigestive cancer. In the pull/push method, one reason for the high complication rate may be that it is necessary to dilate the lumen before treatment when the stenosis caused by the tumor is severe. In many aerodigestive cancer patients, PEG tube placement by pull/push method can be limited by digestive tract stenosis. PEG tube placement using an introducer is the safest alternative in this group of patients but use of the available devices is difficult to implement.

In the past, the introducer technique was technically more demanding and associated with a lower success rate. This problem was solved by the use of T-fasteners to secure the anterior stomach to the abdominal wall[39,40]. Therefore, recent data on the introducer method using T-fasteners show low complication rates of less than 11% and no mortality[38,41-45]. However, Dyck’s study shows that severe short-term complications may occur in patients with esophageal or head and neck tumors after placement of the introducer PEG tube with T-fasteners, leading to urgent surgical intervention and even death in a substantial number of patients[20]. Why the complication and mortality rates were high in Dyck’s study is unclear. Selection bias may be one reason. Van Dyck et al[20] reported that better follow-up of PEG tube daily care might be necessary. In almost all studies, the complication and mortality rates were low. Larger studies on the introducer method in patients with esophageal cancer are needed.

One disadvantage of the introducer method is that only small diameter balloon-type catheters are available and the requirement for frequent catheter changes when long-term tube feeding is needed[42,43]. The modification of the PEG device using the introducer technique is improved in this respect. It allows for the use of a larger-caliber tube with low complication rates and no procedure-related mortality. The direct method reduces the incidence of catheter changes compared with the 20-French catheter in the standard pull/push method. It is also feasible, safe and efficient in outpatients with obstructive head and neck cancer. However, procedure-related severe bleeding associated with the direct method has been reported[46].

TIMING OF PEG TUBE PLACEMENT

Cady[47] reported that patients who require therapeutic PEG tube placement in response to significant weight loss during treatment suffer greater morbidity than patients who receive PEG tubes prophylactically. Patients who have a PEG tube at treatment initiation experience less overall weight loss and fewer hospitalizations and toxicity-related treatment interruptions. However, Locher et al[27] reported that systematic evidence assessing both the benefits and harm associated with prophylactic PEG tube placement in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer is weak and the benefits and potential for harm have not been established.

CONCLUSION

An optimal supportive treatment for aerodigestive carcinoma is not yet available. PEG has many advantages for aerodigestive cancer, although there is insufficient evidence to determine the optimal method of enteral feeding. Enteral nutrition by the introducer method or the direct method must be studied with an emphasis on the long-term effectiveness and safety of supportive therapy of the aerodigestive cancer.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Bustamante-Balen M, Levine EA, Nishida T, Shimoyama S S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:18–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<18::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javle M, Ailawadhi S, Yang GY, Nwogu CE, Schiff MD, Nava HR. Palliation of malignant dysphagia in esophageal cancer: a literature-based review. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:365–373, 379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conigliaro R, Battaglia G, Repici A, De Pretis G, Ghezzo L, Bittinger M, Messmann H, Demarquay JF, Togni M, Blanchi S, et al. Polyflex stents for malignant oesophageal and oesophagogastric stricture: a prospective, multicentric study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:195–203. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328013a418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dakkak M, Hoare RC, Maslin SC, Bennett JR. Oesophagitis is as important as oesophageal stricture diameter in determining dysphagia. Gut. 1993;34:152–155. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyata H, Yano M, Yasuda T, Hamano R, Yamasaki M, Hou E, Motoori M, Shiraishi O, Tanaka K, Mori M, et al. Randomized study of clinical effect of enteral nutrition support during neoadjuvant chemotherapy on chemotherapy-related toxicity in patients with esophageal cancer. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motoori M, Yano M, Yasuda T, Miyata H, Peng YF, Yamasaki M, Shiraishi O, Tanaka K, Ishikawa O, Shiozaki H, et al. Relationship between immunological parameters and the severity of neutropenia and effect of enteral nutrition on immune status during neoadjuvant chemotherapy on patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Oncology. 2012;83:91–100. doi: 10.1159/000339694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabor S, Renner H, Matzi V, Ratzenhofer B, Lindenmann J, Sankin O, Pinter H, Maier A, Smolle J, Smolle-Jüttner FM. Early enteral feeding compared with parenteral nutrition after oesophageal or oesophagogastric resection and reconstruction. Br J Nutr. 2005;93:509–513. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita T, Daiko H, Nishimura M. Early enteral nutrition reduces the rate of life-threatening complications after thoracic esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer. Eur Surg Res. 2012;48:79–84. doi: 10.1159/000336574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bozzetti F, Braga M, Gianotti L, Gavazzi C, Mariani L. Postoperative enteral versus parenteral nutrition in malnourished patients with gastrointestinal cancer: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu GH, Liu ZH, Wu ZH, Wu ZG. Perioperative artificial nutrition in malnourished gastrointestinal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2441–2444. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braga M, Gianotti L, Gentilini O, Parisi V, Salis C, Di Carlo V. Early postoperative enteral nutrition improves gut oxygenation and reduces costs compared with total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:242–248. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siersema PD. New developments in palliative therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:959–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homs MY, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Palliative therapy. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:246–256. doi: 10.1002/jso.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Tanaka N, Fujii H, Kajiyama M. Prospective randomized trial comparing the direct method using a 24 Fr bumper-button-type device with the pull method for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2008;40:722–726. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker AT, Gourin CG, Ghegan MD, Porubsky ES, Martindale RG, Terris DJ. ‘Push’ versus ‘pull’ percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1898–1902. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster JM, Filocamo P, Nava H, Schiff M, Hicks W, Rigual N, Smith J, Loree T, Gibbs JF. The introducer technique is the optimal method for placing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes in head and neck cancer patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:897–901. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockeld D, Fagerberg J, Granström L, Backman L. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy for nutrition in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:839–844. doi: 10.1080/11024150152717670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabie AS. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in cancer patients; technique, indications and complications. Gulf J Oncolog. 2010;(7):37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagishita A, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Takizawa K, Yamaguchi Y, Matsubayashi H, Ono H. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy using the direct method for aerodigestive cancer patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:77–81. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834dfd67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyck E, Macken EJ, Roth B, Pelckmans PA, Moreels TG. Safety of pull-type and introducer percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes in oncology patients: a retrospective analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuercher BF, Grosjean P, Monnier P. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in head and neck cancer patients: indications, techniques, complications and results. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:623–629. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1412-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grilo A, Santos CA, Fonseca J. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy for nutritional palliation of upper esophageal cancer unsuitable for esophageal stenting. Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:227–231. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032012000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corry J, Poon W, McPhee N, Milner AD, Cruickshank D, Porceddu SV, Rischin D, Peters LJ. Randomized study of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tubes for enteral feeding in head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo) radiation. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:503–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2008.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sur R, Donde B, Falkson C, Ahmed SN, Levin V, Nag S, Wong R, Jones G. Randomized prospective study comparing high-dose-rate intraluminal brachytherapy (HDRILBT) alone with HDRILBT and external beam radiotherapy in the palliation of advanced esophageal cancer. Brachytherapy. 2004;3:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homs MY, Eijkenboom WM, Coen VL, Haringsma J, van Blankenstein M, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. High dose rate brachytherapy for the palliation of malignant dysphagia. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nugent B, Lewis S, O’Sullivan JM. Enteral feeding methods for nutritional management in patients with head and neck cancers being treated with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD007904. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007904.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Locher JL, Bonner JA, Carroll WR, Caudell JJ, Keith JN, Kilgore ML, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, Tajeu GS, Allison JJ. Prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in treatment of head and neck cancer: a comprehensive review and call for evidence-based medicine. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:365–374. doi: 10.1177/0148607110377097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellrichmann M, Sergeev P, Bethge J, Arlt A, Topalidis T, Ambrosch P, Wiltfang J, Fritscher-Ravens A. Prospective evaluation of malignant cell seeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with oropharyngeal/esophageal cancers. Endoscopy. 2013;45:526–531. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin HS, Ibrahim HZ, Kheng JW, Fee WE, Terris DJ. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: strategies for prevention and management of complications. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1847–1852. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200110000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson DR, Harig JM, Kozarek RA, Kelsey PB, Picha GJ. Placement of a feeding button (“one-step button”) as the initial procedure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:501–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maetani I, Tada T, Ukita T, Inoue H, Sakai Y, Yoshikawa M. PEG with introducer or pull method: a prospective randomized comparison. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:837–841. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)70017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MC. Cancer metastasis at percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy stomata is related to the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of circulating tumor cells. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3288–3291. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baredes S, Behin D, Deitch E. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding in patients with head and neck cancer. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:417–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hujala K, Sipilä J, Pulkkinen J, Grenman R. Early percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy nutrition in head and neck cancer patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:847–850. doi: 10.1080/00016480410017440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehrsson YT, Langius-Eklöf A, Bark T, Laurell G. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) - a long-term follow-up study in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:740–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandu A, Smith AC, Douglas M. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients undergoing resection for oral tumors: a retrospective review of complications and outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saunders JR, Brown MS, Hirata RM, Jaques DA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with head and neck malignancies. Am J Surg. 1991;162:381–383. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giordano-Nappi JH, Maluf-Filho F, Ishioka S, Hondo FY, Matuguma SE, Simas de Lima M, Lera dos Santos M, Retes FA, Sakai P. A new large-caliber trocar for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy by the introducer technique in head and neck cancer patients. Endoscopy. 2011;43:752–758. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown AS, Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT. Controlled percutaneous gastrostomy: nylon T-fastener for fixation of the anterior gastric wall. Radiology. 1986;158:543–545. doi: 10.1148/radiology.158.2.2934763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson FM, Crombleholme TM, Latchaw LA, Jacir NN. Modification of the “push” technique for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in infants and children. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wejda BU, Deppe H, Huchzermeyer H, Dormann AJ. PEG placement in patients with ascites: a new approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:178–180. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dormann AJ, Glosemeyer R, Leistner U, Deppe H, Roggel R, Wigginghaus B, Huchzermeyer H. Modified percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) with gastropexy--early experience with a new introducer technique. Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:933–938. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dormann AJ, Wejda B, Kahl S, Huchzermeyer H, Ebert MP, Malfertheiner P. Long-term results with a new introducer method with gastropexy for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1229–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shastri YM, Hoepffner N, Tessmer A, Ackermann H, Schroeder O, Stein J. New introducer PEG gastropexy does not require prophylactic antibiotics: multicenter prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shigoka H, Maetani I, Tominaga K, Gon K, Saitou M, Takenaka Y. Comparison of modified introducer method with pull method for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: prospective randomized study. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:426–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koide T, Inamori M, Kusakabe A, Uchiyama T, Watanabe S, Iida H, Endo H, Hosono K, Sakamoto Y, Fujita K, et al. Early complications following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: results of use of a new direct technique. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1639–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cady J. Nutritional support during radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: the role of prophylactic feeding tube placement. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:875–880. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.875-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]