Abstract

Background

In 2005, maximum safe surgical resection, followed by radiotherapy with concomitant temozolomide (TMZ), followed by adjuvant TMZ became the standard of care for glioblastoma (GBM). Furthermore, a modest, but meaningful, population-based survival improvement for GBM patients occurred in the US between 1999 (when TMZ was first introduced) and 2008. We hypothesized that TMZ usage explained this GBM survival improvement.

Methods

We used national Veterans Health Adminis-tration (VHA) databases to construct a cohort of GBM patients, with detailed treatment information, diagnosed 1997–2008 (n = 1645). We compared survival across 3 periods of diagnosis (1997–2000, 2001–2004, and 2005–2008) using Kaplan–Meier curves. We used proportional hazards models to calculate period hazard rate ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for demographic, clinical, and treatment covariates.

Results

Survival increased over calendar time (stratified log-rank P < .0001). After adjusting for age and Charlson comorbidity score, for cases diagnosed in 2005–2008 versus 1997–2000, the HR was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.64–0.82; p-trend < .0001). Sequentially adding non-TMZ treatment variables (ie, surgery, radiotherapy, non-TMZ chemotherapy) to the model did not change this result. However, adding TMZ to the model containing age, Charlson comorbidity score, and all non-TMZ treatments eliminated the period effect entirely (HR = 1.01; 95% CI, 0.86–1.19; p-trend = 0.84).

Conclusions

The observed survival improvement among GBM patients diagnosed in the VHA system between 1997 and 2008 was completely explained by TMZ. Similar studies in other populations are warranted to test the generalizability of our finding to other patient cohorts and health care settings.

Keywords: brain neoplasms, glioblastoma, survival, temozolomide, time trends

In 1999, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the alkylating agent temozolomide (TMZ) for the treatment of recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma.1 Between 1999 and 2005, off-label use of TMZ for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) became increasingly widespread,2–6 culminating in the adoption in 2005 of maximum safe surgical resection, followed by radiotherapy with concomitant TMZ, followed by adjuvant TMZ as the new standard of care.7 This treatment advance was based on a landmark phase III trial in which patients with newly diagnosed, microscopically confirmed GBM were randomized to receive radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant TMZ.8 Median survival was 12.1 months in the group that received radiotherapy alone compared with 14.6 months in the group that received radiotherapy plus TMZ.

However, efficacy in a clinical trial does not guarantee effectiveness in the general population. Using GBM cases diagnosed between 1993 and 2007 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program database, we previously demonstrated a modest, but meaningful, population-based survival improvement for GBM patients in the US that began in 1999–2001 and continued through 2005–2007.9 Others have also utilized SEER to demonstrate this survival improvement.10–12

Although we showed a close ecologic association between increasing TMZ usage and improved survival,9 we were unable to directly test the hypothesis that TMZ usage explained the improved survival because SEER does not include information on chemotherapy treatment. We proposed that the rising TMZ usage in 1999–2007 was the most likely explanation for the survival improvement, but we could not rule out the possibility that other treatment advances, such as greater extent of surgical resection13–17 or more aggressive treatment of recurrent disease,18,19 also contributed.

In the current study, we constructed a cohort of patients diagnosed with GBM between 1997 and 2008, including detailed treatment and follow-up information, based on national Veterans Health Administration (VHA) databases. We utilized this cohort to directly test the hypothesis that TMZ usage explained the GBM survival improvement observed during this period.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

All cancer cases diagnosed or treated at VHA medical centers are reported to the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry (VACCR). We obtained the VACCR records for all glioma cases (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition [ICD-O-3]20 morphology codes between 9380 and 9460, with behavior code 3 [malignant]) diagnosed between 1997 and 2007 and for most cases diagnosed in 2008.

We used each VHA patient's unique identifier to link our VACCR glioma cohort with data from other VHA national databases, including pharmacy, inpatient and outpatient encounters (at VHA facilities and at non-VHA facilities when paid for by the VHA), and the diagnosis and procedure codes associated with the encounters.

The current study included microscopically confirmed GBM cases diagnosed between 1997 and 2008. We defined GBM as ICD-O-3 morphology codes 9440–9442 in combination with ICD-O-3 topography code C71 (brain). We excluded 11 cases diagnosed by autopsy only and 17 cases with insufficient treatment information. In addition to its standard coded variables, the VACCR database includes text fields describing pathology, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and diagnostic procedures. We required that cases be coded as microscopically confirmed in the VACCR diagnostic confirmation field or that microscopic confirmation be clearly indicated in the pathology text field. We also required that the VACCR surgical diagnostic procedure field, VACCR surgical treatment field, VACCR surgery text field, or procedure codes associated with inpatient or outpatient encounters indicate that a biopsy was performed.

We assumed the VACCR morphology field was correct unless review of the pathology text field indicated otherwise. Through this review, we determined 14 cases to have been miscoded as GBM. The pathology text field for these cases indicated “anaplastic astrocytoma,” “low-grade glioma,” “glioblastoma grade II,” “astrocytic neoplasm with no necrosis seen,” or “WHO grade III.” Furthermore, we reclassified 65 cases coded in the registry as non-GBM gliomas to be GBM. Most of the pathology text fields for these cases indicated “glioblastoma” or “astrocytoma, grade IV.” Some text fields indicated high-grade or malignant glioma or astrocytoma with necrosis and/or endothelial/vascular proliferation, which are pathognomonic for GBM.21 Our final GBM cohort included 1645 cases. This study was approved by institutional review boards at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and Yale School of Medicine. The study was granted a waiver of informed consent.

Variables

For all variables, coders were blind to the outcome (survival). For each subject, we compared information on sex, date of birth, race/ethnicity, and marital status from the VACCR, inpatient encounter, and outpatient encounter records. The few discrepancies among data sources were resolved using the best available evidence. For example, if sex was coded as male in the VACCR record but as female in most or all inpatient and outpatient encounter records, we considered the sex to be female; if Hispanic ethnicity was coded as unknown in the VACCR record but as Hispanic in inpatient or outpatient encounter records, we considered the ethnicity to be Hispanic.

We obtained the following sociodemographic variables from the VACCR: Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) of the reporting VHA medical center (the VHA is organized into 21 geographically based VISNs); primary payer at diagnosis; and diagnosis/treatment facility, which indicates whether diagnosis and/or first course of treatment took place at the reporting VHA medical center or elsewhere. We obtained data on individual annual income from the inpatient encounter closest within 1 year of the GBM date of diagnosis. Income was converted to 2008 dollars using Consumer Price Index conversion factors.22

We used two measures of comorbidity. We obtained “service-connected disability” (determined to help establish eligibility for VHA benefits and measured as a percentage in 10% increments) from inpatient and outpatient encounter records, selecting the value recorded closest in time to the date of GBM diagnosis, but restricted to the year prior to diagnosis. If no such value was recorded, we allowed a value within 30 days after the date of diagnosis. We calculated a Charlson comorbidity score23,24 from International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision25 (ICD-9) diagnosis codes recorded in inpatient and outpatient encounter records ranging from 2 years before to 30 days after the GBM date of diagnosis. The following diagnoses (as determined by ICD-9 codes) are included in the score: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease, and diabetes (1 point each); diabetes with chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, and any malignancy (2 points each); moderate or severe liver disease (3 points); and metastatic solid tumors and AIDS (6 points each). We required that a comorbid condition be recorded in 1 inpatient encounter or in at least 2 outpatient encounters on 2 different days. We completely excluded from the index calculation ICD-9 code 191 (malignant neoplasm of brain), as well as comorbid conditions recorded during the period 90 days before to 30 days after the GBM date of diagnosis that might have been caused by or confused with GBM (ie, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, hemiplegia or paraplegia, and secondary malignant neoplasms of brain and spinal cord).

We obtained data on treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) from a variety of data sources. We obtained type and date of surgery, radiotherapy (yes/no), and radiotherapy dates from the VACCR (both coded variables and text fields) and from ICD-9 procedure codes and Current Procedural Terminology26 codes recorded in inpatient and outpatient encounter records. We determined extent of resection from VACCR codes and the VACCR surgery text field. This variable was primarily based on the surgeon's impression as determined from the operative report, but in some instances was based on the postoperative MRI report. We obtained type and dates of chemotherapy mainly from the pharmacy database but also utilized VACCR coded variables and text fields.

To reconcile differences among the various data sources, we utilized the best available evidence based on decision rules for each treatment variable. For example, if the VACCR code indicated no resection, but procedure codes indicated a resection, we coded the subject as having had a resection. This could occur if the reporting facility was not the treatment facility. Similarly, if the VACCR code indicated radiotherapy but there were no radiotherapy procedure codes, we coded the subject as having received radiotherapy. This could occur if radiotherapy was performed by an outside facility and was not paid for by the VHA, but by Medicare, for example.

We defined date of GBM diagnosis as the earliest surgery date at which a microscopic diagnosis was made. We calculated age at diagnosis from the date of birth and date of diagnosis. The VACCR includes data on vital status and date of death or last contact. We updated these dates through September 2011 by linkage with the national VHA vital status database.

Available records did not allow us to determine the date of GBM recurrence, so we were unable to directly distinguish between first course chemotherapy and chemotherapy administered for recurrent disease. Instead, we defined chemotherapy as first course if it was the initial course administered and was started <6 months after diagnosis or <4 months after the end date of radiotherapy. All other chemotherapy was defined as later course. In distinguishing between first and later course, we took into consideration typical patterns of care. For example, within the first course time window, adjuvant TMZ administered following concomitant TMZ and radiotherapy was considered to be first course, but bevacizumab (now standard therapy for recurrence27) administered after termination of TMZ, or TMZ administered after termination of carmustine (which occurred before TMZ became first course standard of care), was considered to be later course.

Statistical Analyses

The study endpoint was overall survival. We measured survival time as the time from the date of GBM diagnosis to the date of death or date of last contact. We categorized our primary predictor variable, calendar year of diagnosis, into 3 four-year periods: 1997–2000, 2001–2004, and 2005–2008.

We used SAS v9.2 for analyses. All statistical tests were 2-sided with α = 0.05. We used PROC PHREG to estimate hazard rate ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for death from Cox proportional hazards regression models. Multivariate Cox models included period of diagnosis (our primary predictor variable), age at diagnosis (≤39 y, 40–44, 45–49, … 80–84, 85+) and baseline Charlson comorbidity score (0, ≥1, unknown). We found no meaningful alteration in the period of diagnosis HRs adjusted for age and Charlson comorbidity score by further adjusting for sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic White, Black, other/unknown), marital status (married, single, divorced/separated, widowed, unknown), VISN of reporting facility, income ($0, quartiles of income >$0, unknown), primary payer (VA, other), diagnosis/treatment facility (4 categories: diagnosis and first course of treatment took place at the reporting VHA medical center [reporting/reporting], diagnosis took place at the reporting center/first course of treatment took place elsewhere [reporting/elsewhere], elsewhere/reporting, and elsewhere/elsewhere), and service-connected disability (percent, unknown), so these covariates were not included in the final multivariate models. We calculated a P-value for period of diagnosis trend (p-trend) by including period of diagnosis in the model as a single ordinal variable.

Treatment covariates in the multivariate models included surgery (biopsy only, partial resection, gross total resection, resection not otherwise specified), radiotherapy (yes, no, unknown), first course non-TMZ chemotherapy (yes, no, unknown), later course non-TMZ chemotherapy (yes, no, unknown), first course TMZ chemotherapy (yes, no, unknown), and later course TMZ chemotherapy (yes, no, unknown). In these analyses, we did not distinguish between concomitant and adjuvant first course TMZ. We modeled each treatment as a time-updated covariate, such that it held the value of 0 before the treatment start date, and the value of 1 on and after the start date. This allowed treatment effects (especially chemotherapy) not to be influenced by cases that did not receive treatments because patients did not live long enough.

We used PROC LIFETEST to generate Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to period of diagnosis and to calculate the percent of subjects alive at 1 year and 2 years (and 95% CIs), median survival (and interquartile range), and a log-rank test and stratified log-rank test (by age and baseline Charlson comorbidity score) of homogeneity across periods of diagnosis.

We performed Kaplan–Meier survival and Cox proportional hazards analyses both for the full cohort of 1645 cases and for a restricted cohort of 932 cases treated with resection and radiotherapy. Because patients in the restricted cohort were deemed eligible for these treatments by their physicians and were willing to undergo these treatments, they may be more homogeneous with respect to eligibility for and willingness to undergo TMZ chemotherapy, possibly lowering the potential impact of confounding by indication (ie, patients with a better prognosis were more likely to be treated with TMZ).28

Results

Of the 1645 cases in the cohort, 1618 (98.4%) died during the observation period. Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of cases. Ninety-seven percent of cases were male. The majority of cases were between ages 55 and 74 years at diagnosis; age at diagnosis increased over calendar time due to the aging of the VHA population. More than four-fifths of cases were non-Hispanic White. Overall, more than a quarter of cases had service-connected disability and about half had a Charlson comorbidity score ≥1 (indicating at least one major comorbidity); these proportions increased over calendar time.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of cases by period of diagnosis

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Years | Period of Diagnosis |

||||

| (1997–2008) | 1997–2000 | 2001–2004 | 2005–2008 | Pa | |

| Deaths/Cases | 1618/1645 | 516/518 | 582/586 | 520/541 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1598 (97) | 500 (97) | 568 (97) | 530 (98) | .34 |

| Female | 47 (3) | 18 (3) | 18 (3) | 11 (2) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||||

| 25–54 | 323 (20) | 133 (26) | 122 (21) | 68 (13) | <.0001 |

| 55–64 | 548 (33) | 133 (26) | 198 (34) | 217 (40) | |

| 65–74 | 441 (27) | 155 (30) | 135 (23) | 151 (28) | |

| 75+ | 333 (20) | 97 (19) | 131 (22) | 105 (19) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1368 (83) | 437 (84) | 477 (81) | 454 (84) | .29 |

| Hispanic White | 73 (4) | 25 (5) | 20 (3) | 28 (5) | |

| Black | 165 (10) | 50 (10) | 68 (12) | 47 (9) | |

| Other/unknown | 39 (2) | 6 (1) | 21 (4) | 12 (2) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 900 (55) | 280 (54) | 311 (53) | 309 (57) | .71 |

| Single | 175 (11) | 61 (12) | 59 (10) | 55 (10) | |

| Divorced/separated | 452 (27) | 143 (28) | 171 (29) | 138 (26) | |

| Widowed | 112 (7) | 32 (6) | 43 (7) | 37 (7) | |

| Unknown | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Geographic regionb | |||||

| Northeast | 185 (11) | 53 (10) | 68 (12) | 64 (12) | .18 |

| Midwest | 349 (21) | 110 (21) | 139 (24) | 100 (18) | |

| South | 706 (43) | 217 (42) | 255 (44) | 234 (43) | |

| West | 405 (25) | 138 (27) | 124 (21) | 143 (26) | |

| Income | |||||

| $0 | 195 (12) | 68 (13) | 71 (12) | 56 (10) | .24 |

| Q1 (median $6288) | 332 (20) | 117 (23) | 122 (21) | 93 (17) | |

| Q2 (median $14 595) | 331 (20) | 106 (20) | 124 (21) | 101 (19) | |

| Q3 (median $27 245) | 332 (20) | 107 (21) | 116 (20) | 109 (20) | |

| Q4 (median $47 472) | 332 (20) | 90 (17) | 117 (20) | 125 (23) | |

| Unknown | 123 (7) | 30 (6) | 36 (6) | 57 (11) | |

| Primary payer | |||||

| VA | 1351 (82) | 455 (88) | 476 (81) | 420 (78) | <.0001 |

| Other | 294 (18) | 63 (12) | 110 (19) | 121 (22) | |

| Diagnosis/treatment facilityc | |||||

| Reporting/reporting | 1070 (65) | 345 (67) | 391 (67) | 334 (62) | <.0001 |

| Reporting/elsewhere | 93 (6) | 20 (4) | 29 (5) | 44 (8) | |

| Elsewhere/reporting | 413 (25) | 103 (20) | 147 (25) | 163 (30) | |

| Elsewhere/elsewhere | 69 (4) | 50 (10) | 19 (3) | 0 | |

| Service-connected disability | |||||

| 0% | 1108 (67) | 346 (67) | 404 (69) | 358 (66) | .013 |

| 10%–40% | 224 (14) | 65 (13) | 82 (14) | 77 (14) | |

| 50%–100% | 206 (13) | 45 (9) | 70 (12) | 91 (17) | |

| Unknown | 107 (7) | 62 (12) | 30 (5) | 15 (3) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||||

| 0 | 735 (45) | 261 (50) | 251 (43) | 223 (41) | .0006 |

| ≥1 | 832 (51) | 223 (43) | 305 (52) | 304 (56) | |

| Unknown | 78 (5) | 34 (7) | 30 (5) | 14 (3) | |

aChi-square test (with unknowns excluded) comparing the proportions of demographic and clinical characteristics across the 3 periods of diagnosis.

bBased on geographic location of the VISN of the reporting VHA medical center.

cIndicates whether diagnosis and first course of treatment occurred at the reporting VHA medical center (reporting) vs another facility (elsewhere).

Table 2 shows the treatment received by cases. One-quarter of cases had a biopsy, but no resection; this proportion increased over calendar time. About three-quarters of cases received radiotherapy during the first course of treatment. Only 9% of cases received first course non-TMZ chemotherapy; this proportion decreased over calendar time, corresponding with the increased use of first course TMZ. About one-third of cases received first course TMZ; as expected, the proportion receiving first course TMZ increased over calendar time, from only 3% in 1997–2000 to more than two-thirds in 2005–2008. In the restricted cohort of 932 cases treated with resection and radiotherapy, 46% received first course TMZ, with the proportion increasing from 5% in 1997–2000 to 92% in 2005–2008 (not shown in table).

Table 2.

Treatment received by cases by period of diagnosis

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Years | Period of Diagnosis |

||||

| (1997–2008) | 1997–2000 | 2001–2004 | 2005–2008 | Pa | |

| Deaths/Cases | 1618/1645 | 516/518 | 582/586 | 520/541 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Biopsy only | 426 (26) | 118 (23) | 149 (25) | 159 (29) | <.0001 |

| Partial resection | 654 (40) | 201 (39) | 246 (42) | 207 (38) | |

| Gross total resection | 271 (16) | 66 (13) | 101 (17) | 104 (19) | |

| Resection NOS | 294 (18) | 133 (26) | 90 (15) | 71 (13) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||||

| No | 404 (25) | 123 (24) | 163 (28) | 118 (22) | .054 |

| Yes | 1203 (73) | 380 (74) | 410 (70) | 413 (76) | |

| Unknown | 38 (2) | 15 (3) | 13 (2) | 10 (2) | |

| Median months to radiotherapy | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| Non-TMZ chemotherapyb | |||||

| First course | |||||

| No | 1476 (90) | 434 (84) | 526 (90) | 516 (95) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 145 (9) | 73 (14) | 51 (9) | 21 (4) | |

| Unknown | 24 (1) | 11 (2) | 9 (2) | 4 (1) | |

| Median months to treatment | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | |

| Later course | |||||

| No | 1534 (93) | 494 (95) | 554 (95) | 486 (90) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 87 (5) | 13 (3) | 23 (4) | 51 (9) | |

| Unknown | 24 (1) | 11 (2) | 9 (2) | 4 (1) | |

| Median months to treatment | 11.5 | 11.5 | 9.7 | 12.2 | |

| TMZ chemotherapy | |||||

| First course | |||||

| No | 1063 (65) | 497 (96) | 414 (71) | 152 (28) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 562 (34) | 17 (3) | 162 (28) | 383 (71) | |

| Unknown | 20 (1) | 4 (1) | 10 (2) | 6 (1) | |

| Median months to treatment | 1.2 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| Later course | |||||

| No | 1521 (92) | 490 (95) | 529 (90) | 502 (93) | .16 |

| Yes | 82 (5) | 23 (4) | 37 (6) | 22 (4) | |

| Unknown | 42 (3) | 5 (1) | 20 (3) | 17 (3) | |

| Median months to treatment | 11.2 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 13.7 | |

Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified.

aChi-square test (with unknowns excluded) comparing the proportions of treatment modalities across the 3 periods of diagnosis.

bIncludes carmustine (BCNU), lomustine (CCNU), procarbazine, vincristine, carboplatin, cisplatin, hydroxyurea, irinotecan, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, topotecan, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, tirapazamine, capecitabine, crisnatol mesylate, motexafin gadolinium, talampanel, bevacizumab, erlotinib, Gliadel wafer, tamoxifen, isotretinoin, tretinoin, thalidomide, O6-benzylguanine, methotrexate.

Median time from diagnosis date to initiation of chemotherapy was 1.3 months for first course non-TMZ chemotherapy, 1.2 months for first course TMZ chemotherapy, 11.5 months for later course non-TMZ chemotherapy, and 11.2 months for later course TMZ chemotherapy (Table 2). Eighty-three percent of the subjects receiving first course TMZ chemotherapy initiated chemotherapy concomitant with first course radiotherapy (not shown in table). More than 90% of the subjects receiving first course TMZ chemotherapy initiated chemotherapy within 16 weeks of diagnosis, as did 84% of subjects receiving first course non-TMZ chemotherapy (not shown in table).

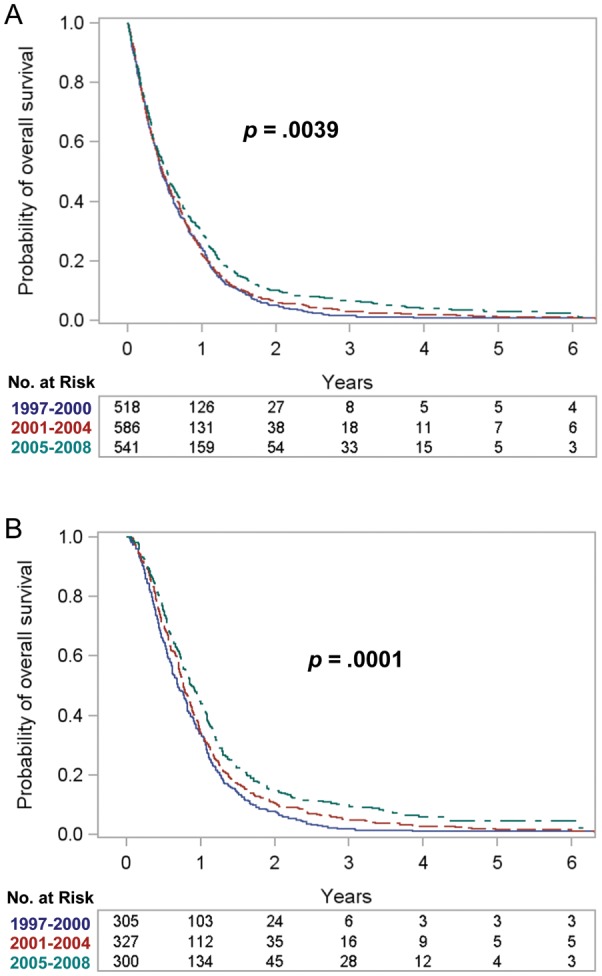

Figure 1 shows Kaplan–Meier survival plots according to period of diagnosis; associated survival statistics are shown in Table 3. We observed survival to be superior among cases diagnosed in 2005–2008 (eg, 2-year survival doubled from 5.2% in 1997–2000 to 10.2% in 2005–2008 in the full cohort and from 7.9% to 15.3% in cases treated with resection and radiotherapy).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival plots according to period of diagnosis. (A) Full cohort (n = 1645). (B) Restricted cohort (treated with resection and radiotherapy) (n = 932).

Table 3.

Survival statistics by period of diagnosis

| Kaplan–Meier Survival Statistics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths/Cases | 1-y, % (95% CI) | 2-y, % (95% CI) | Median, mo (interquartile range) | |

| Full cohort | ||||

| All years (1997–2008) | 1618/1645 | 25.3 (23.2–27.4) | 7.3 (6.1–8.6) | 5.8 (2.6–12.1) |

| Period of diagnosis | ||||

| 1997–2000 | 516/518 | 24.3 (20.7–28.1) | 5.2 (3.5–7.4) | 5.5 (2.6–11.8) |

| 2001–2004 | 582/586 | 22.4 (19.1–25.8) | 6.5 (4.7–8.7) | 5.7 (2.5–11.7) |

| 2005–2008 | 520/541 | 29.4 (25.6–33.3) | 10.2 (7.8–13.0) | 6.4 (2.8–13.2) |

| Log-rank test Pa | .0039 | |||

| Stratified log-rank test Pb | <.0001 | |||

| Restricted cohort (treated with resection and radiotherapy) | ||||

| All years (1997–2008) | 910/932 | 37.5 (34.3–40.5) | 11.2 (9.3–13.4) | 9.4 (5.3–14.9) |

| Period of diagnosis | ||||

| 1997–2000 | 303/305 | 33.8 (28.5–39.1) | 7.9 (5.2–11.2) | 8.3 (4.7–13.6) |

| 2001–2004 | 324/327 | 34.3 (29.2–39.4) | 10.7 (7.6–14.3) | 9.2 (5.3–14.6) |

| 2005–2008 | 283/300 | 44.7 (39.0–50.2) | 15.3 (11.4–19.6) | 10.6 (6.1–16.9) |

| Log-rank test Pa | .0001 | |||

| Stratified log-rank test Pb | <.0001 | |||

aCompares the Kaplan–Meier survival proportions across the 3 periods of diagnosis.

bCompares the Kaplan–Meier survival proportions across the 3 periods of diagnosis, controlling for age at diagnosis (≤39 y, 40–44, 45–49, … 80–84, 85+) and baseline Charlson comorbidity score (0, ≥1, unknown).

Table 4 shows treatment effects on survival by treatment modality: surgery, radiotherapy, first course non-TMZ chemotherapy, and first course TMZ chemotherapy. HRs were generated from separate multivariate Cox models for each treatment modality, adjusting for period of diagnosis, age, and Charlson comorbidity score (but not for other treatment modalities). In the full cohort, the HRs for treatment with resection (compared with biopsy only), radiotherapy, and first course TMZ chemotherapy were each about 0.5 or less and highly statistically significant (each P < .0001). The HR for first course non-TMZ chemotherapy was 0.83 (P = .036). For the restricted cohort of cases treated with resection and radiotherapy, the HR was 0.60 (P < .0001) for first course TMZ chemotherapy and 0.87 (P = .17) for first course non-TMZ chemotherapy. Because treatment modalities were not modeled simultaneously in the same Cox model, the HRs did not take into account correlation among treatment modalities.

Table 4.

Treatment HRs and 95% CIs for death

| HR (95% CI) (each column represents a separate multivariate Cox modela) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Surgeryb | Model 2: Radiotherapyc | Model 3: First Course Non-TMZ Chemotherapyd | Model 4: First Course TMZ Chemotherapye | ||||

| Full cohort: 1618 deaths/1645 cases | |||||||

| Biopsy only (424/426)f | 1.00 (reference) | No (402/404) | 1.00 (reference) | No (1451/1476) | 1.00 (reference) | No (1058/1063) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Partial resection (641/654) | 0.53 (0.46–0.60) | Yes (1179/1203) | 0.51 (0.45–0.59) | Yes (143/145) | 0.83 (0.69–0.99) | Yes (540/562) | 0.52 (0.45–0.60) |

| Gross total resection (263/271) | 0.41 (0.35–0.48) | P | <.0001 | P | .036 | P | <.0001 |

| Resection NOS (290/294) | 0.45 (0.39–0.53) | ||||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||

| Restricted cohort (treated with resection and radiotherapy): 910 deaths/932 cases | |||||||

| No (778/798) | 1.00 (reference) | No (489/491) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Yes (116/118) | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | Yes (406/426) | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) | ||||

| P | .17 | P | <.0001 | ||||

Abbreviation: NOS, not otherwise specified.

aAdjusted for period of diagnosis (1997–2000, 2001–2004, 2005–2008), age at diagnosis (≤39 y, 40–44, 45–49, … 80–84, 85+), and baseline Charlson comorbidity score (0, ≥1, unknown), with no adjustment for other treatments.

bSurgery (biopsy only, partial resection, gross total resection, resection NOS), modeled as a time-updated variable.

cRadiotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated variable.

dFirst course non-TMZ chemotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated variable.

eFirst course TMZ chemotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated variable.

fDeaths/cases; in each model, numbers in categories may not add to the total number in the cohort because results for the unknown category are not shown.

Table 5 shows period of diagnosis HRs, with 1997–2000 serving as the reference period. For the full cohort, in the univariate model, we observed a significantly decreased HR for cases diagnosed in 2005–2008, consistent with the Kaplan–Meier results. When we added age and Charlson comorbidity score to the model, this period effect was accentuated, with an HR of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.64–0.82) for cases diagnosed in 2005–2008, a period effect P < .0001, and a p-trend <.0001.

Table 5.

Period of diagnosis HRs and 95% CIs for death

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariate HR (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths/Cases | Basea | Base + Surgeryb | Base + Surgery + Radiotherapyc | Base + Surgery + Radiotherapy + First Course Non-TMZ Chemod | Base + Surgery + Radiotherapy + First Course Non-TMZ Chemo + First Course TMZ Chemoe | ||

| Full cohort: 1618 deaths/1645 cases | |||||||

| Period of diagnosis | |||||||

| 1997–2000 | 516/518 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 2001–2004 | 582/586 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.91 (0.80–1.02) | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) |

| 2005–2008 | 520/541 | 0.82 (0.73–0.93) | 0.72 (0.64–0.82) | 0.70 (0.62–0.80) | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) |

| Period effect P | .0040 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .60 | |

| Trend P | .0015 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .84 | |

| Restricted cohort (treated with resection and radiotherapy): 910 deaths/932 cases | |||||||

| Period of diagnosis | |||||||

| 1997–2000 | 303/305 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 2001–2004 | 324/327 | 0.87 (0.75–1.02) | 0.81 (0.69–0.95) | 0.81 (0.69–0.95) | 0.81 (0.69–0.96) | 0.80 (0.68–0.94) | 1.05 (0.87–1.25) |

| 2005–2008 | 283/300 | 0.71 (0.60–0.83) | 0.60 (0.51–0.71) | 0.61 (0.52–0.73) | 0.62 (0.52–0.73) | 0.60 (0.51–0.72) | 1.02 (0.79–1.31) |

| Period effect P | .0002 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .86 | |

| Trend P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .86 | |

Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard rate ratio; TMZ, temozolomide.

aAdjusted for age at diagnosis (≤39 y, 40–44, 45–49, … 80–84, 85+) and baseline Charlson comorbidity score (0, ≥1, unknown).

bAdditionally adjusted for surgery (biopsy only, partial resection, gross total resection, resection not otherwise specified), modeled as a time-updated covariate.

cAdditionally adjusted for radiotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated covariate.

dAdditionally adjusted for first course non-TMZ chemotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated covariate.

eAdditionally adjusted for first course TMZ chemotherapy (no, yes, unknown), modeled as a time-updated covariate.

The period effect (significantly improved survival over calendar time) did not meaningfully change when we sequentially added the non-TMZ treatment variables (surgery, radiotherapy, first course non-TMZ chemotherapy) to the model (Table 5). However, adding first course TMZ chemotherapy to the model containing the baseline covariates and all non-TMZ treatments eliminated the period effect entirely, with an HR for cases diagnosed in 2005–2008 of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.86–1.19), a period effect P-value of .60 and a p-trend of .84. Thus, first course TMZ chemotherapy completely accounted for the improved survival observed over calendar time.

For the restricted cohort of cases treated with resection and radiotherapy, the period effect when first course TMZ chemotherapy was not included in the model was more pronounced than for the full cohort. When we added first course TMZ chemotherapy to the model, the period effect was again entirely abolished (Table 5).

Results of alternative analyses (data not shown) were similar to the analyses presented in Table 5. These analyses included omitting first course non-TMZ chemotherapy from the final model in Table 5, including second course TMZ chemotherapy in the final model and second course non-TMZ chemotherapy in the final 2 models. Furthermore, in the full cohort, adding radiotherapy alone to the base model, without the surgery covariate, did not meaningfully alter the period effect, but when first course TMZ chemotherapy was then added to the model with radiotherapy, the period effect was abolished.

Discussion

In this national VHA population of GBM patients, we observed a statistically significant improvement in survival among cases diagnosed in 2005–2008 compared with cases diagnosed in 1997–2000, along with a significant trend of increasing survival over calendar time. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found this survival improvement to be completely explained by TMZ chemotherapy. Others have observed better survival among non–clinical trial29 or population-based30 patients treated after surgery with radiotherapy and TMZ compared with radiotherapy alone. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to show that TMZ totally explained the improved survival that has occurred on a population level since the turn of the century. Although it is possible that a factor tightly correlated with TMZ use, and not TMZ itself, was responsible for the increased survival, it is not at all apparent what such a factor would be.

In relative terms, the survival improvement among VHA GBM cases diagnosed in 2005–2008 compared with 1997–2000 was similar to the survival improvement observed in the US general population of GBM cases.9–12 However, as we found, and as already reported by others,31 the absolute survival among VHA cases was substantially worse, with a median survival of 6.4 months among VHA cases versus 9.7 months in the general GBM population (SEER) among cases diagnosed in 2005–2008.10 This survival difference is unlikely to be due to VHA cases receiving inferior medical care, given that for other types of cancer, most studies have found quality of care32,33 and/or survival32,34,35 to be the same as or superior in the VHA versus other facilities. Furthermore, the proportions of VHA cases receiving resection,9 radiotherapy,9 and TMZ chemotherapy28 were comparable to the proportions receiving these treatments in the general population of GBM patients.

The disparity in GBM survival between VHA and general population patients was not the focus of the current study, but clearly warrants further research. Possible explanations include greater comorbidity and/or lower performance status among VHA cases. The percent of GBM cases with a Charlson comorbidity score ≥1 was 51% in the current VHA cohort compared with 30% in a sample of GBM cases from SEER.28 Unfortunately, we did not have information on performance status, a known important prognostic factor for GBM.29,36,37 Most cases in our cohort did not receive later course chemotherapy (Table 2). This may have contributed to the survival disparity or may have been a result of later course chemotherapy not being clinically indicated due to high comorbidity and/or low performance status.

We observed confounding toward the null of the period effect by age and Charlson comorbidity score. Thus, in the univariate analysis, the point estimate for the HR for 2005–2008 compared with 1997–2000 was 0.82 (Table 5). However, after adjusting for age and Charlson comorbidity score, the point estimate fell to 0.72 (Table 5), reflecting both the decreasing proportion of younger patients (who are known to have better survival9–12) and the increasing proportion of patients with comorbidity over calendar time (Table 1). Similarly, the Kaplan–Meier survival plots (Fig. 1) reflected a univariate examination of survival that did not take age or comorbidity into account. Thus, in the full cohort, the log-rank P-value was .0039, whereas the log-rank P-value stratified for age and Charlson comorbidity score was <.0001 (Table 3).

Our study had the strength of utilizing several sources of information from national VHA databases. First, the VACCR pathology text field allowed us to perform quality control on the ICD-O-3 morphology codes and thus refine the classification of cases as GBM. Second, using the national vital status database, we updated follow-up through September 2011. Third, linking the VACCR with other national VHA databases enabled us to include covariates not collected by VACCR (eg, service-connected disability, Charlson comorbidity score) and to construct a treatment history for each case that was substantially more complete than that contained in the VACCR database alone. Importantly, construction of the non-TMZ and TMZ chemotherapy treatment histories would not have been possible without the pharmacy database, which was the primary data source for these variables. Nevertheless, although we captured treatments received at non-VHA facilities paid for by the VHA, we most likely missed some treatment that took place in non-VHA facilities not paid for by the VHA.

We were unable to directly distinguish between first course chemotherapy and later course chemotherapy administered for recurrent disease because we were unable to determine date of recurrence. However, it is not likely that there was substantial misclassification of first course versus later course chemotherapy. For 83% of the subjects we classified as having received first course TMZ chemotherapy, the chemotherapy was initiated concomitant with first course radiotherapy, indicating that the TMZ was, indeed, first course. Furthermore, more than 90% of the subjects we classified as having received first course TMZ chemotherapy initiated chemotherapy within 16 weeks of diagnosis, as did 84% of subjects we classified as having received first course non-TMZ chemotherapy.

Our cohort was predominantly non-Hispanic White male, reflecting the preponderance of males in the overall VHA population and the higher GBM incidence rate in non-Hispanic Whites compared with non-Whites.38 Veterans served by VHA tend to have substantial comorbidity, service-connected disabilities, and limited economic resources.39,40 Thus, GBM patients in the VHA may not be representative of GBM patients from the general US population.

In summary, we observed a survival improvement among GBM patients diagnosed in the national VHA system between 1997 and 2008 that was completely explained by TMZ chemotherapy. Similar studies in other populations are warranted to test the generalizability of our finding to other patient cohorts and health care settings.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1 R03 CA150048). L.S.P. was supported by training grant 5 T32 MH020031 (J. Ickovics, PI) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry (VACCR) for providing us with a dataset of glioma cases. This study would not have been possible without the VACCR's generous assistance. We are also grateful for the support and resources provided by the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

References

- 1.Clinical Trials and Noteworthy Treatments for Brain Tumors Web site, August 1999. Schering-Plough announces FDA approval of TEMODAR(TM) (temozolomide) capsules for patients with refractory anaplastic astrocytoma: first new chemotherapy agent for brain tumors in 20 years. http://www.virtualtrials.com/temodar%5Cpress.cfm . Accessed 3 January 2013.

- 2.Danson SJ, Middleton MR. Temozolomide: a novel oral alkylating agent. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1:13–19. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mason WP, Cairncross JG. Drug insight: temozolomide as a treatment for malignant glioma—impact of a recent trial. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:88–95. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher DJ, Henson JW, Avutu B, et al. The added value of concurrently administered temozolomide versus adjuvant temozolomide alone in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2008;88:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9530-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinjamuri M, Adumala RR, Altaha R, Hobbs GR, Crowell EB., Jr. Comparative analysis of temozolomide (TMZ) versus 1,3-bis (2-chloroethyl)-1 nitrosourea (BCNU) in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) patients. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:221–225. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiemels JL, Wilson D, Patil C, et al. IgE, allergy, and risk of glioma: update from the San Francisco Bay Area Adult Glioma Study in the temozolomide era. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:680–687. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MH, Johnson JR, Pazdur R. Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary: temozolomide plus radiation therapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6767–6771. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darefsky AS, King JT, Jr., Dubrow R. Adult glioblastoma multiforme survival in the temozolomide era: a population-based analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries. Cancer. 2012;118:2163–2172. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DR, O'Neill BP. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J Neurooncol. 2012;107:359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koshy M, Villano JL, Dolecek TA, et al. Improved survival time trends for glioblastoma using the SEER 17 population-based registries. J Neurooncol. 2012;107:207–212. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence YR, Mishra MV, Werner-Wasik M, et al. Improving prognosis of glioblastoma in the 21st century: who has benefited most? Cancer. 2012;118:4228–4234. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asthagiri AR, Pouratian N, Sherman J, Ahmed G, Shaffrey ME. Advances in brain tumor surgery. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:975–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piepmeier JM. The future of neuro-oncology. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;51:1343–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanai N, Berger MS. Operative techniques for gliomas and the value of extent of resection. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen HJ for the ALA-Glioma Study Group. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stummer W, van den Bent MJ, Westphal M. Cytoreductive surgery of glioblastoma as the key to successful adjuvant therapies: new arguments in an old discussion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:1211–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain MC. What role should cilengitide have in the treatment of glioblastoma? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman SA, Ye X, Piantadosi S, et al. Survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with radiation and temozolomide in research studies in the United States. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2443–2449. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI inflation calculator. 2012. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl . Accessed 6 November 2012.

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site, 1998. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9.htm . Accessed 4 October 2012.

- 26.Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton JA, et al. Current Procedural Terminology, CPT 2010. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beal K, Abrey LE, Gutin PH. Antiangiogenic agents in the treatment of recurrent or newly diagnosed glioblastoma: analysis of single-agent and combined modality approaches. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabroff KR, Harlan L, Zeruto C, Abrams J, Mann B. Patterns of care and survival for patients with glioblastoma multiforme diagnosed during 2006. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:351–359. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rock K, McArdle O, Forde P, et al. A clinical review of treatment outcomes in glioblastoma multiforme—the validation in a non-trial population of the results of a randomised phase III clinical trial: has a more radical approach improved survival? Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e729–e733. doi: 10.1259/bjr/83796755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronning PA, Helseth E, Meling TR, Johannesen TB. A population-based study on the effect of temozolomide in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:1178–1184. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arrigo RT, Boakye M, Skirboll SL. Patterns of care and survival for glioblastoma patients in the Veterans population. J Neurooncol. 2012;106:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Tomlinson JS, et al. Quality of pancreatic cancer care at Veterans Administration compared with non–Veterans Administration hospitals. Am J Surg. 2007;194:588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:727–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komrokji RS, Matacia-Murphy GM, Al Ali NH, et al. Outcome of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes in the Veterans Administration population. Leuk Res. 2010;34:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, et al. Survival of older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus fee-for-service Medicare. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1072–1079. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaichana K, Parker S, Olivi A, Quinones-Hinojosa A. A proposed classification system that projects outcomes based on preoperative variables for adult patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:997–1004. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.JNS09805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorlia T, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, et al. Nomograms for predicting survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: prognostic factor analysis of EORTC and NCIC trial 26981–22981/CE.3. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubrow R, Darefsky AS. Demographic variation in incidence of adult glioma by subtype, United States, 1992–2007. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Gaziano JM, Horner RD, Feussner JR. US Department of Veterans Affairs medical care system as a resource to epidemiologists. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:307–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Justice AC, Erdos J, Brandt C, Conigliaro J, Tierney W, Bryant K. The Veterans Affairs healthcare system: a unique laboratory for observational and interventional research. Med Care. 2006;44:S7–S12. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228027.80012.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]