Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma multiforme with an oligodendroglial component (GBMO) has been recognized in the World Health Organization classification—however, the diagnostic criteria, molecular biology, and clinical outcome of primary GBMO remain unclear. Our aim was to investigate whether primary GBMO is a distinct clinicopathological subgroup of GBM and to determine the relative frequency of prognostic markers such as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on 1p and/or 19q, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation, and isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutation.

Methods

We examined 288 cases of primary GBM and assessed the molecular markers in 57 GBMO and 50 cases of other primary GBM, correlating the data with clinical parameters and outcome.

Results

GBMO comprised 21.5% of our GBM specimens and showed significantly longer survival compared with our other GBM (12 mo vs 5.8 mo, P = .006); there was also a strong correlation with younger age at diagnosis (56.4 y vs 60.6 y, P = .005). Singular LOH of 19q (P = .04) conferred a 1.9-fold increased hazard of shorter survival. There was no difference in the frequencies of 1p or 19q deletion, MGMT promoter methylation, or IDH1 mutation (P = .8, P = 1.0, P = 1.0, respectively).

Conclusions

Primary GBMO is a subgroup of GBM associated with longer survival and a younger age group but shows no difference in the frequency of LOH of 1p/19q, MGMT, and IDH1 mutation compared with other primary GBM.

Keywords: glioblastoma with an oligodendroglial component, histopathology, 1p/19q, IDH1, MGMT

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and malignant primary brain tumor. The majority arise de novo (primary GBM), but a small proportion progress from low-grade glioma (secondary GBM). The survival rate of GBM remains low compared with other high-grade human malignancies despite the most recent advances in treatment of combined surgical resection with radiotherapy and temozolomide, with only a small proportion of patients surviving more than 36 months.1,2

Histologically, GBM is characterized by high cellularity, high mitotic activity, necrosis, and microvascular proliferation. The neoplastic cells are highly heterogeneous. Although the majority of GBM tumors have astrocytic differentiation, other morphologies (such as small cell, multinucleated giant cell, sarcomatous, gemistocytic, and oligodendroglial-like cells) may also be present in varying proportions.1

In the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system (2007), it was recognized that occasional GBM contains foci that resemble oligodendroglioma and it was advised that such tumors be classified as glioblastoma with an oligodendroglial component (GBMO).1 This addition is based mainly on previous studies in which GBMO tumors were found to be ∼5%–20% of GBM and show an improved survival rate compared with other types of GBM.3–6 GBMO is reported to have genetic alterations similar to other GBM but to differ in harboring a higher rate of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at 1p or 19q and less frequent loss of 10q, PTEN mutation, and CDKN2A deletion.3–6 LOH of 1p/19q has been reported in a high proportion of tumors with oligodendroglial differentiation and is associated with good prognosis.7–9 Salavati et al.10 observed an improved prognosis for GBM with oligodendroglial differentiation and associated 1p/19q deletions.

Despite this, GBMO terminology, diagnostic criteria, and outcome remain uncertain. It is not clear whether GBMO is a distinct subgroup of GBM with focal oligodendroglial differentiation or rather represents a collection of mixed oligoastrocytomas (MOAs) with necrosis. To this end, Miller et al.11 found that a series of MOAs with necrosis had a worse prognosis than histologically similar tumors without necrosis and therefore suggested labeling them MOA grade IV; however, this group of tumors still harbored a better overall survival than conventional GBM.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether GBMO represented a distinct subgroup of primary GBM based upon its clinicopathological characteristics and a series of routinely used predictive molecular markers, specifically LOH of 1p/19q, promoter methylation status of O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) and mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 gene (IDH1). Focusing on these 3 commonly and clinically used molecular markers would shed light on the nature of the oligodendroglial morphology observed in GBMO and help to differentiate it from other GBM in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

This study was performed with approval from the local research ethics committee.

Case Selection

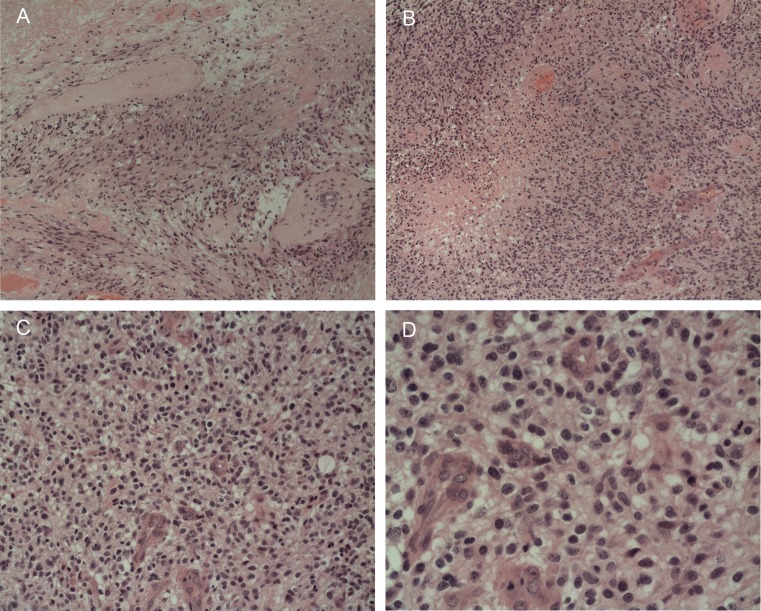

We selected 288 consecutive GBM tumors from the past 4 years from the archives of King's College Hospital, London, for which sufficient surgically resected (not biopsied) formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material and clinical data were available. The cases were reviewed by 2 pathologists (S.P., S.A-S.) and classified according to the most frequent cellular morphology. Tumors that were classified as glioblastoma with focal oligodendroglial differentiation included areas of ∼10%–30% of tumor cells exhibiting monotonous appearances of rounded nuclei, perinuclear halo, compactness of cells, and branching blood vessels (Fig. 1). They show other areas typical of GBM with predominantly astrocytic differentiation, pseudopalisading necrosis, and prominent vascular hyperplasia, including glomeruloid structures.1 The latter 3 histological features were used to exclude cases of anaplastic oligodendroglioma or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma based on the current (2007) WHO classification.

Fig. 1.

A case of GBMO (ID 44) with 19q loss. There is (A) cellular and anaplastic predominant astrocytic differentiation with (B) prominent vascular hyperplasia and pseudopalisading necrosis. (C and D) A focal area of oligodendroglial differentiation with rounded anaplastic nuclei and perinuclear halo separated by hyperplastic blood vessels.

Molecular Studies

Molecular analysis was carried out on a subset of 107 cases of the total 288 cases of glioblastoma. This subset included 57 GBMO and 50 non-GBMO.

Genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue using the WaxFree DNA kit (TrimGen). Bisulfite conversion was performed using an EpiTect kit (Qiagen), and MGMT promoter methylation status was analyzed using methylation-specific PCR.12 IDH1 R132H mutation immunohistochemistry analysis was carried out in the manner set out by Capper and colleagues.13,14 Sequencing detection of the IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in GBMO tumors was done as reported previously.15 LOH of 1p/19q was determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization with 1p36/1q25 or 19q/19p locus-specific identifier DNA dual color probes (Vysis, Abbott Diagnostics) as reported elsewhere.16 At least 100 nonoverlapping nuclei were counted (200 for marginal cases); deletions of 1p or 19q were called if the percentage of nuclei with a deletion was ≥25%, and the ratio of signals was ≤0.75. The Mann–Whitney U-test17 was taken into account for borderline results.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software. Fisher's exact test was used for contingency tables; reported P values were 2-tailed, P < .05 being considered significant. Student’s t test was used for comparisons of mean age. Overall survival was studied by the Kaplan–Meier method (Mantel–Cox) with Cox regression for multivariate analysis.

Results

All GBM

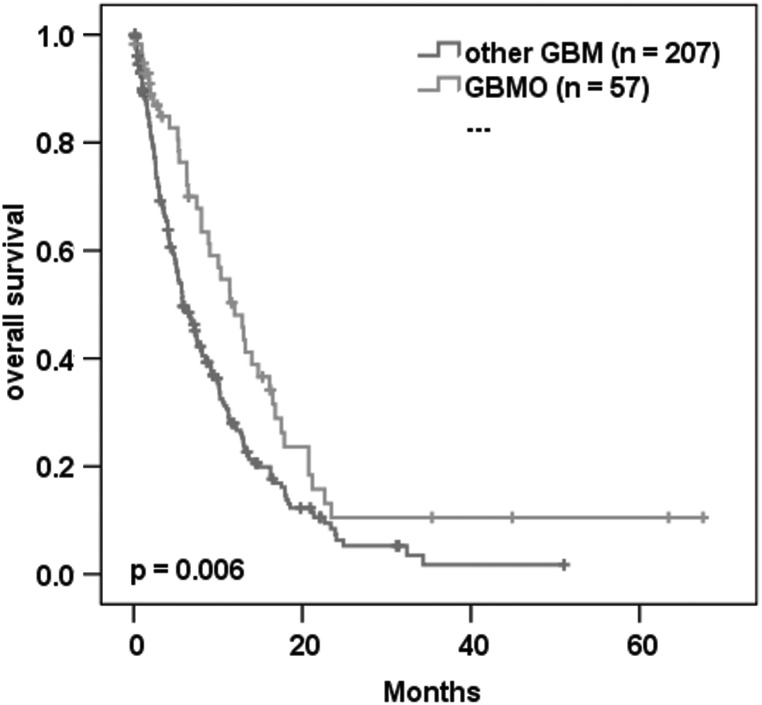

Histological review of 288 consecutive glioblastoma cases receiving either subtotal or total resection revealed 62 (21.5%) to be GBMO. The GBMO group showed significantly longer median survival compared with the other glioblastoma samples (12 mo vs 5.8 mo, P = .006; Fig. 2); there was also a strong correlation with younger age (56.4 y vs 60.6 y, P = .005). When excluding patients receiving no adjuvant treatment, the median survival difference between GBMO and other types of GBM was less pronounced but still significant (n = 171; 14 mo vs 10 mo, P < .05).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of 264 GBM showing the association with overall survival of GBMO compared with other-GBM.

Molecular Comparison Subset

The molecular analysis subset (n = 107) was composed of the following histological types: 57 (53.3%) oligodendroglial, 36 (33.6%) fibrillary, 6 (5.6%) gemistocytic, 4 (3.7%) small cell, 2 (1.9%) giant cell, and 2 (1.9%) sarcomatous. The 50 non-GBMO tumors are hereafter referred to as other-GBM.

The clinical and molecular details of the molecular comparison subset are shown in Table 1. The relative distributions of molecular markers and clinical parameters between the GBMO group and the other-GBM group are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical and molecular data of the molecular comparison subset

| ID | GBMO/ Other-GBM | Age/ Gender | Surgery (resection) | Treatment | 1p/19q LOH | MGMT Promoter Methylation | IDH1 | Survival (mo) | Censor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GBMO | 60.2/M | Subtotal | Nil | NA | Unmethylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 2 | GBMO | 51.4/F | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 2 | Censored |

| 3 | GBMO | 68.8/F | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 35 | Censored |

| 4 | GBMO | 68.6/F | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 3 | Censored |

| 5 | GBMO | 51.4/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 0 | Event |

| 6 | GBMO | 75.5/M | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 19q | Unmethylated | wt | 12 | Event |

| 7 | GBMO | 66.6/F | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | mut | 5 | Event |

| 8 | GBMO | 73.7/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 1 | Event |

| 9 | GBMO | 44.0/M | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 19q | Methylated | mut | 1 | Event |

| 10 | GBMO | 32.7/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 11 | GBMO | 65.2/M | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 1p | Unmethylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 12 | GBMO | 77.8/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 7 | Censored |

| 13 | GBMO | 65.7/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | NA | Unmethylated | NA | 63 | Censored |

| 14 | GBMO | 48.2/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 68 | Censored |

| 15 | GBMO | 49.5/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 1 | Censored |

| 16 | GBMO | 41.7/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | NA | wt | 2 | Censored |

| 17 | GBMO | 67.7/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 10 | Event |

| 18 | GBMO | 71.3/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 19 | GBMO | 42.2/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 9 | Event |

| 20 | GBMO | 58.3/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | methylated | wt | 11 | Event |

| 21 | GBMO | 51.9/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 23 | Event |

| 22 | GBMO | 70.8/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 3 | Event |

| 23 | GBMO | 55.5/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 8 | Event |

| 24 | GBMO | 66.0/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 1p | Unmethylated | wt | 10 | Event |

| 25 | GBMO | 67.2/F | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 1 | Censored |

| 26 | GBMO | 69.3/F | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 2 | Censored |

| 27 | GBMO | 54.9/F | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 1 | Censored |

| 28 | GBMO | 65.7/M | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 7 | Event |

| 29 | GBMO | 62.8/F | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 5 | Event |

| 30 | GBMO | 45.4/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 31 | GBMO | 40.4/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 11 | Event |

| 32 | GBMO | 40.7/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 21 | Event |

| 33 | GBMO | 44.5/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 6 | Event |

| 34 | GBMO | 54.9/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 23 | Event |

| 35 | GBMO | 44.1/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 21 | Event |

| 36 | GBMO | 38.2/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 37 | GBMO | 60.1/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 18 | Event |

| 38 | GBMO | 49.9/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 13 | Event |

| 39 | GBMO | 51.2/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 13 | Event |

| 40 | GBMO | 58.4/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 15 | Event |

| 41 | GBMO | 51.2/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 16 | Event |

| 42 | GBMO | 52.0/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 9 | Event |

| 43 | GBMO | 44.6/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | mut | 21 | Event |

| 44 | GBMO | 51.8/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 16 | Event |

| 45 | GBMO | 34.9/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | NA | wt | 5 | Event |

| 46 | GBMO | 46.6/M | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 16 | Censored |

| 47 | GBMO | 41.8/M | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 45 | Censored |

| 48 | GBMO | 49.4/M | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | NA | wt | 15 | Censored |

| 49 | GBMO | 60.1/F | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 14 | Event |

| 50 | GBMO | 42.9/M | NA | NA | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 51 | GBMO | 69.2/M | NA | NA | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 0 | Censored |

| 52 | GBMO | 52.9/F | Subtotal | NA | No LOH | Methylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 53 | GBMO | 65.5/F | Subtotal | NA | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 3 | Censored |

| 54 | GBMO | 63.2/F | Subtotal | NA | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 17 | Event |

| 55 | GBMO | 66.6/F | Subtotal | NA | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 13 | Event |

| 56 | GBMO | 64.5/M | Subtotal | NA | NA | Methylated | wt | 6 | Event |

| 57 | GBMO | 72.8/M | Subtotal | NA | LOH 19q | Unmethylated | wt | 8 | Event |

| 58 | Other-GBM | 76.0/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 1 | Event |

| 59 | Other-GBM | 80.0/F | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 60 | Other-GBM | 63.9/F | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 1p | Unmethylated | wt | 1 | Event |

| 61 | Other-GBM | 65.0/M | Subtotal | Nil | LOH 19q | Unmethylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 62 | Other-GBM | 46.8/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 0 | Event |

| 63 | Other-GBM | 78.1/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 64 | Other-GBM | 72.5/M | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 0 | Event |

| 65 | Other-GBM | 72.9/F | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 66 | Other-GBM | 66.0/F | Subtotal | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 2 | Event |

| 67 | Other-GBM | 79.1/F | Total | Nil | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 0 | Censored |

| 68 | Other-GBM | 53.3/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 1p | Unmethylated | wt | 12 | Event |

| 69 | Other-GBM | 73.7/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 5 | Event |

| 70 | Other-GBM | 72.7/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 71 | Other-GBM | 69.2/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 7 | Event |

| 72 | Other-GBM | 65.6/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | NA | Unmethylated | wt | 7 | Event |

| 73 | Other-GBM | 71.1/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 74 | Other-GBM | 65.2/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 5 | Event |

| 75 | Other-GBM | 79.1/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 3 | Event |

| 76 | Other-GBM | 52.2/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 18 | Event |

| 77 | Other-GBM | 50.3/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 13 | Event |

| 78 | Other-GBM | 53.0/F | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 1p | Unmethylated | wt | 5 | Event |

| 79 | Other-GBM | 67.5/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 9 | Event |

| 80 | Other-GBM | 69.0/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 5 | Event |

| 81 | Other-GBM | 44.8/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 10 | Event |

| 82 | Other-GBM | 51.9/M | Subtotal | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 6 | Event |

| 83 | Other-GBM | 59.0/M | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 3 | Censored |

| 84 | Other-GBM | 70.5/M | Total | Radiotherapy | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 10 | Event |

| 85 | Other-GBM | 80.8/M | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 7 | Event |

| 86 | Other-GBM | 48.9/M | Total | Radiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 87 | Other-GBM | 45.8/F | Total | Radiotherapy | LOH 19q | Methylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 88 | Other-GBM | 47.3/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 89 | Other-GBM | 55.9/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 22 | Censored |

| 90 | Other-GBM | 48.4/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 51 | Censored |

| 91 | Other-GBM | 47.1/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | mut | 20 | Censored |

| 92 | Other-GBM | 31.4/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 21 | Censored |

| 93 | Other-GBM | 60.3/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 13 | Event |

| 94 | Other-GBM | 58.8/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 25 | Event |

| 95 | Other-GBM | 33.7/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | mut | 16 | Event |

| 96 | Other-GBM | 67.6/F | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 32 | Event |

| 97 | Other-GBM | 47.3/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 18 | Event |

| 98 | Other-GBM | 58.3/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | LOH 1p | Methylated | wt | 21 | Event |

| 99 | Other-GBM | 57.0/M | Subtotal | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 24 | Event |

| 100 | Other-GBM | 55.2/F | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Methylated | wt | 22 | Censored |

| 101 | Other-GBM | 62.1/F | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 31 | Censored |

| 102 | Other-GBM | 61.3/F | Total | Chemoradiotherapy | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 7 | Event |

| 103 | Other-GBM | 46.4/M | NA | NA | LOH 19q | Unmethylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 104 | Other-GBM | 56.0/F | NA | NA | No LOH | Methylated | wt | NA | NA |

| 105 | Other-GBM | 68.2/M | Subtotal | NA | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | 4 | Event |

| 106 | Other-GBM | 38.8/M | Subtotal | NA | NA | Unmethylated | NA | 5 | Event |

| 107 | Other-GBM | 57.0/M | Total | NA | No LOH | Unmethylated | wt | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; mut, mutation; wt, wild type.

Table 2.

Distribution of clinical parameters and molecular markers between GBMO and other-GBM

| Parameter | All GBM | GBMO | Other-GBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 107 | n = 57 | n = 50 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 58.0 | 56.2 | 60.0 | P = .1 |

| Median | 58.3 | 54.9 | 59.6 | |

| Range | 31–81 | 33–78 | 31–81 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 58 | 30 | 28 | P = .8 |

| Female | 49 | 27 | 22 | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Subtotal | 84 | 46 | 38 | P = .6 |

| Total | 19 | 9 | 10 | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Nil | 21 | 11 | 10 | P = .7 |

| Radiotherapy | 38 | 18 | 20 | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 35 | 20 | 15 | |

| LOH 1p/19q | ||||

| No deletion | 75 | 41 | 34 | P = .8 |

| 1p deletion | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| 19q deletion | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Codeletion | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MGMT | ||||

| Methylated | 57 | 30 | 27 | P = 1 |

| Unmethylated | 47 | 24 | 23 | |

| IDH1 | ||||

| Wild type | 100 | 53 | 47 | P = 1 |

| Mutation | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

A trend for younger mean age in the GBMO group compared with the other-GBM group was seen, but it was not significant (56.2 y vs 60 y, P = .1; Table 2). There were no significant differences for gender, extent of surgery, or treatment (P = .8, P = .6, P = .7, respectively; Table 2). No 1p/19q codeletions were detected in GBMO or in other-GBM. There was little or no difference in the frequencies of singular 1p or 19q deletion, MGMT promoter methylation, or IDH1 mutation (P = .8, P = 1.0, P = 1.0, respectively; Table 2). IDH1 mutation was correlated with younger age in the whole molecular comparison subset (47.2 y vs 58.6 y, P = .04). The majority of GBMO tumors were additionally tested by sequence analysis. There were no rare mutations of IDH1 detected or any IDH2 mutations. R132H mutations were in agreement with the immunohistochemistry (data not shown).

Univariate Survival Analysis

Univariate analyses found only 3 parameters that showed significant prognostic effect: patient age, treatment, and solitary 19q deletion. Kaplan–Meier analysis for the molecular comparison subset showed only a trend for extended overall survival in GBMO versus other-GBM (12 mo vs 6.7 mo, P = .36). Older age (Cox proportional hazard) was correlated with poorer prognosis (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.01–1.06; P = .005). Postoperative therapy—comprising no therapy, radiotherapy, and chemoradiotherapy—was the most prognostic factor (median overall survival 1.9 mo, 7.3 mo, and 20.8 mo, respectively; P = 1.5E-8). Also of interest was the highly significant association of 19q deletion having a poorer prognosis than no deletion (P = .004; Fig. 3A). This association was not significant in GBMO only cases, but remained significant for the other-GBM group (P = .1 and P = .01, respectively; Fig. 3B and C). There was a small increase in overall survival for MGMT methylation, but it was not significant (10.1 mo vs 8 mo, P = .6). IDH1 mutation was not seen to be prognostic either (P = .7).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier plots of the association of the LOH status of 1p/19q with overall survival in (A) the molecular comparison subset, (B) the GBMO group only, (C) the other-GBM group only.

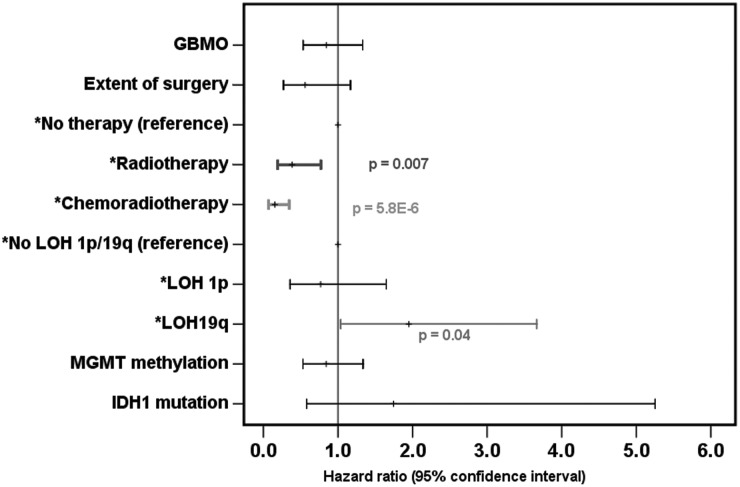

Multivariate Survival Analyses

All multivariate analyses were adjusted for age and gender. The GBMO group showed a reduced hazard (HR = 0.84) but it is not significant (P = .46). Radiotherapy, with reference to no therapy, had a significantly reduced hazard (HR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.19–0.77, P = .007, Fig. 4A). Chemoradiotherapy, again with reference to no therapy, showed the largest reduction in hazard (HR = 0.15, 95% CI = 0.07–0.35, P = 5.8E-6; Fig. 4). Singular deletion of 19q remained associated with worse prognosis compared with no deletion (HR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.04–3.66, P = .04; Fig. 4). Age remains prognostic in all the analyses except when adjusted for treatment; no other parameters were significantly prognostic.

Fig. 4.

A forest plot representing Cox proportional multivariate analyses of overall survival, adjusted for age and gender.

Discussion

We selected our cases based on the latest (2007) WHO classification for brain tumors, all with clear and nondisputed diagnosis of GBM but with a small proportion of oligodendroglial morphology ranging from 10% to ∼30% of the tumor samples. In our 57 cases of GBMO, we excluded the tumors that were diagnosed as oligodendrogliomas or oligoastrocytomas. According to the available clinical information, we believe that all of our selected cases were considered primary GBM, with none having any clinical or radiological evidence of progression from a low-grade glioma.

We found GBMO to be present in about 21.5% of our GBM series, which is consistent with other studies reporting 17%4 and 20%.6 One study, however, showed a lower (5%) frequency of GBMO.5 We found the average survival rate in our group of GBMO to be significantly longer (P = .006) at 12 months compared with 5.8 months for other-GBM. When excluding patients receiving no adjuvant treatment, the median survival difference between GBMO and other-GBM was less pronounced but still significant (n = 171; 14 mo vs 10 mo, P < .05). These figures are consistent with the findings of other investigators.3,18,19 In agreement with other studies, we also found that the age at diagnosis in this group of patients was younger than for other-GBM. The mean age at diagnosis of GBMO was 56.4 years compared with 60.6 years for GBM (P = .005); the younger age group of GBMO may have contributed to the better survival rate. Therefore, based on morphological appearances, longer survival rate, and younger age at diagnosis, it appears that GBMO represents a subset of primary glioblastomas. However, when we studied the commonly and routinely used predictive molecular markers, the distinction of this group became less obvious.

We chose to investigate the 1p/19q status because of its known importance and link to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of oligodendroglial tumors. In all the studied cases, we found a total of 11.8% with 1p deletion, 14.7% with 19q deletion, and none with codeletion. In GBMO, 11.1% had 1p deletion compared with 12.5% in other-GBM, while 19q deletion was present in 13% in GBMO compared with 16.7% in other-GBM. Therefore, it seems that the frequency of 1p and 19q deletions are comparable or slightly lower compared with other studies, in which the frequency is reported to be 10%–25%.

We used fluorescence in situ hybridization for 1p/19q deletion, which is widely used in clinical practice. Other studies, which used a different methodology (like comparative genomic hybridization or PCR microsatellite LOH) to detect the deletion, found a larger proportion of partial deletion of 1p, but the 1p large deletion was similar to those seen typically in oligodendrogliomas and was observed in only a few cases. However, from clinical and treatment points of view, the large deletion rather than the small focal deletion in 1p and 19q is related to improved prognosis and response to therapy.20 Therefore, we think that the large or significant deletion of 1p and 19q (similar to those seen in oligodendrogliomas) is rare in glioblastomas.

Interestingly, in our study, the frequency of 1p or 19q loss was similar in both GBMO and other-GBM. Morphological appearances were unaffected by loss on 1p or 19q for these 2 sets of tumors. If we consider that the combined 1p/19q deletion or singular 1p loss is one of the diagnostic features of oligodendroglioma, our results with no combined deletion and equal proportion of 1p deletion only in the 2 sets of GBM indicate that the oligodendroglial differentiation may not be genuine and that these areas may have only morphological similarities to oligodendroglioma (oligodendroglial-like areas) rather than true oligodendroglial differentiation.

Another important implication of 1p/19q status is its prognostic and predictive value due to the clinical importance of detecting 1p and/or 19q loss in oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas. However, the impact of loss of 1p or 19q in GBM is not consistent in the published literature. Some reported better survival with codeletion.6,21 However, others, like Houillier et al.22 and Shih et al.,23 reported no improved survival with the deletion. In our study, we did not have a case of codeletion of 1p/19q, but in our series, cases with singular 1p and singular 19q deletion did not have improved survival. On the contrary, we found that loss of 19q in univariate and multivariate analyses was associated with poor prognosis. This is consistent with other published literature24,25; we also had similar observations in our own series of lower-grade (II) diffuse gliomas (data not published).

MGMT promoter methylation is predictive for chemotherapy response and longer survival in GBM.26,27 We did not find a prognostic association for MGMT; however, our results did show that methylated and unmethylated MGMT were of similar proportions in GBMO (55.6% and 44.4%, respectively) and other-GBM (54% and 46%) and indicate that this epigenetic marker has no correlation with the morphological appearances of GBM.

IDH1 mutation has not previously been reported in the context of GBMO.3–6,10,11 The overall proportion of GBM with IDH1 mutation (4.8%) was consistent with other published frequencies of IDH1 mutation in primary GBM as a whole,13,28 and the proportion of IDH1 mutation in GBMO at 5.4% supports the notion that our cases were truly primary GBM and not anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (AOA) or anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO) with necrosis. Similarly, they are unlikely to have progressed from a lower-grade oligodendroglial tumor, otherwise IDH1 would have been observed in a significantly higher proportion of cases. The IDH1 mutation is a reliable marker that allows separation of primary GBM from other, secondary GBM and anaplastic gliomas. However, it still remains unclear whether a clinically well-defined primary GBM with IDH1 mutation represents a secondary GBM that has progressed rapidly from a clinically silent low-grade glioma. The few glioblastoma cases with IDH1 mutation (total 5/105) appear to have no better survival or distinguishing morphological features than their wild-type counterparts, though the small numbers preclude a rigorous conclusion. It appears, however, that the impact of IDH1 status on prognosis and survival of primary GBM is not as informative as its status with anaplastic gliomas (AOA, AO, and anaplastic astrocytoma).

It seems likely that we need to consider oligodendroglial-like areas in otherwise typical GBM as a focal morphological differentiation or metaplastic change occurring in a genetically highly volatile primary glial brain tumor. It is well known that primary GBM may show additional morphological features, such as focal ependymal differentiation with vascular pseudorosettes or even mesenchymal (gliosarcoma) and epithelial differentiation. Such focal aberrant differentiation would not change the diagnosis, management, or treatment of the GBM. Depending on the IDH1 and 1p/19q results, it appears that primary GBMO is probably a different tumor from and should not be confused with oligoastrocytoma with necrosis, although the latter may be assigned to WHO grade IV.24,25

In conclusion, our results suggest that GBMO is a subgroup of GBM associated with better survival, most likely due to the involvement of a younger age group. The association of singular 19q deletion with a worse prognosis has not been previously reported in GBM and warrants further investigation. The GBMO in this series was differentiated from anaplastic gliomas by virtue of predominantly astrocytic differentiation, pseudopalisading necrosis, and prominent vascular hyperplasia, including glomeruloid structures. Under these criteria, GBMO showed no difference in frequency of 1p, 19q, methylated MGMT, or IDH1 mutation compared with other GBM. We believe that GBMO should be considered as biologically distinct from AO and AOA with necrosis, by virtue of their IDH1 and 1p/19q status.

Funding

This work was supported by King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, which funded R&D grants 2010/11. S. P., A. J., and C. J. acknowledge NHS funding to the Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ray Chaudhuri, Majid Kazmi, and Claire Troakes for their kind support.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krex D, Klink B, Hartmann C, et al. Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraus JA, Lamszus K, Glesmann N, et al. Molecular genetic alterations in glioblastomas with oligodendroglial component. Acta Neuropathologica. 2001;101(4):311–320. doi: 10.1007/s004010000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He J, Mokhtari K, Sanson M, et al. Glioblastomas with an oligodendroglial component: a pathological and molecular study. J Neuropathol Exper Neurol. 2001;60(9):863–871. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.9.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilton DA, Penney M, Pobereskin L, Sanders H, Love S. Histological indicators of prognosis in glioblastomas: retinoblastoma protein expression and oligodendroglial differentiation indicate improved survival. Histopathology. 2004;44(6):555–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homma T, Fukushima T, Vaccarella S, et al. Correlation among pathology, genotype, and patient outcomes in glioblastoma. J Neuropathol Exper Neurol. 2006;65(9):846–854. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000235118.75182.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauman GS, Ino Y, Ueki K, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 1p and radiotherapy plus chemotherapy in patients with oligodendrogliomas. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(3):825–830. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00703-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairncross JG, Macdonald DR. Successful chemotherapy for recurrent malignant oligodendroglioma. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(4):360–364. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macdonald DR, Gaspar LE, Cairncross JG. Successful chemotherapy for newly diagnosed aggressive oligodendroglioma. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(5):573–574. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvati M, Formichella AI, D'Elia A, et al. Cerebral glioblastoma with oligodendrogliomal component: analysis of 36 cases. J Neuro-Oncol. 2009;94(1):129–134. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller CR, Dunham CP, Scheithauer BW, Perry A. Significance of necrosis in grading of oligodendroglial neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(34):5419–5426. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteller M, Hamilton SR, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Inactivation of the DNA repair gene O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation is a common event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capper D, Weissert S, Balss J, et al. Characterization of R132H mutation-specific IDH1 antibody binding in brain tumors. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(1):245–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capper D, Zentgraf H, Balss J, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Monoclonal antibody specific for IDH1 R132H mutation. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009;118(5):599–601. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, et al. Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009;118(4):469–474. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Tatagiba M, et al. Molecular markers in low-grade gliomas: predictive or prognostic? Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(13):4588–4599. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of 2 random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann Math Stat. 1947;18(1):50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donahue B, Scott CB, Nelson JS, et al. Influence of an oligodendroglial component on the survival of patients with anaplastic astrocytomas: a report of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 83–02. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38(5):911–914. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green RE, Krause J, Ptak SE, et al. Analysis of one million base pairs of neanderthal DNA. Nature. 2006;444(7117):330–336. doi: 10.1038/nature05336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichimura K, Vogazianou AP, Liu L, et al. 1p36 is a preferential target of chromosome 1 deletions in astrocytic tumours and homozygously deleted in a subset of glioblastomas. Oncogene. 2008;27(14):2097–2108. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt MC, Antweiler S, Urban N, et al. Impact of genotype and morphology on the prognosis of glioblastoma. J Neuropathol Exper Neurol. 2002;61(4):321–328. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houillier C, Lejeune J, Benouaich-Amiel A, et al. Prognostic impact of molecular markers in a series of 220 primary glioblastomas. Cancer. 2006;106(10):2218–2223. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shih HA, Betensky RA, Dorfman MV, Louis DN, Loeffler JS, Batchelor TT. Genetic analyses for predictors of radiation response in glioblastoma. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(3):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadji M, Fortin D, Tsanaclis AM, Drouin R. Is the 1p/19q deletion a diagnostic marker of oligodendrogliomas? Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;194(1):12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheie D, Meling TR, Cvancarova M, et al. Prognostic variables in oligodendroglial tumors: a single-institution study of 95 cases. Neuro-Oncology. 2011;13(11):1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Deimling A, Korshunov A, Hartmann C. The next generation of glioma biomarkers: MGMT methylation, BRAF fusions and IDH1 mutations. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(1):74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegi ME, Diserens A, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. New Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang XS, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]