Abstract

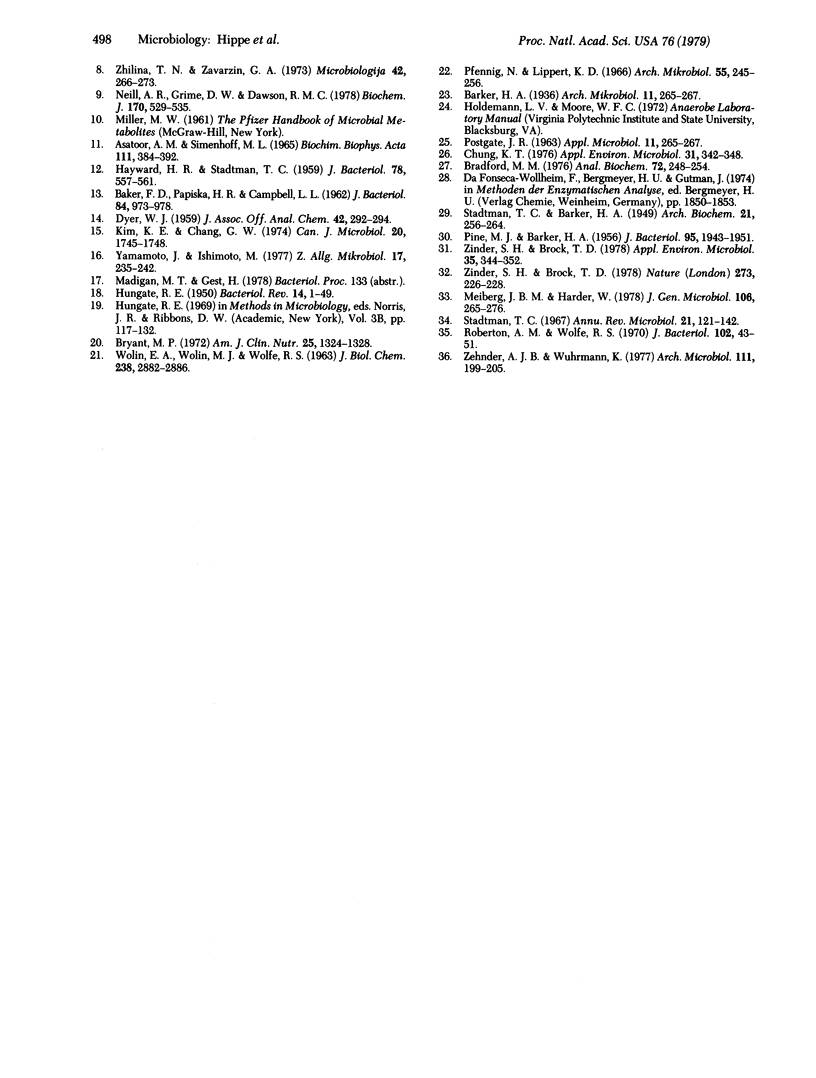

A number of N-methyl compounds, including several methylamines, creatine, sarcosine, choline, and betaine, were readily fermented by enrichment cultures yielding methane as a major product. Methylamine, dimethylamine, trimethylamine, and ethyldimethylamine were fermented by pure cultures of Methanosarcina barkeri; except for ethyldimethylamine, these amines are considered important substrates of this methanogenic microorganism. Creatine, sarcosine, choline, and betaine were fermented to methane only by mixed cultures. During growth of M. barkeri on methyl-, dimethyl-, or trimethylamine, methanol was not excreted into the medium. The fermentation of trimethylamine gave rise to an intermediary accumulation of methyl- and dimethylamine in the medium. An accumulation of methylamine during the fermentation of dimethylamine was not observed. Methane and ammonia were produced from the three methylamines by M. barkeri in amounts expected on the basis of the appropriate fermentation equations. The growth yield was 5.8 mg of cells (dry weight) per mmol of methane and was not dependent on the kind of methyl compound used as substrate.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Asatoor A. M., Simenhoff M. L. The origin of urinary dimethylamine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965 Dec 16;111(2):384–392. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(65)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKER F. D., PAPISKA H. R., CAMPBELL L. L. Choline fermentation by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. J Bacteriol. 1962 Nov;84:973–978. doi: 10.1128/jb.84.5.973-978.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M. P. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972 Dec;25(12):1324–1328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. T. Inhibitory effects of H2 on growth of Clostridium cellobioparum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976 Mar;31(3):342–348. doi: 10.1128/aem.31.3.342-348.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYWARD H. R., STADTMAN T. C. Anaerobic degradation of choline. I. Fermentation of choline by an anaerobic, cytochrome-producing bacterium, Vibrio cholinicus n. sp. J Bacteriol. 1959 Oct;78:557–561. doi: 10.1128/jb.78.4.557-561.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNGATE R. E. The anaerobic mesophilic cellulolytic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1950 Mar;14(1):1–49. doi: 10.1128/br.14.1.1-49.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. E., Chang G. W. Trimethylamine oxide reduction by Salmonella. Can J Microbiol. 1974 Dec;20(12):1745–1748. doi: 10.1139/m74-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah R. A., Ward D. M., Baresi L., Glass T. L. Biogenesis of methane. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:309–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill A. R., Grime D. W., Dawson R. M. Conversion of choline methyl groups through trimethylamine into methane in the rumen. Biochem J. 1978 Mar 15;170(3):529–535. doi: 10.1042/bj1700529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POSTGATE J. R. Versatile medium for the enumeration of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1963 May;11:265–267. doi: 10.1128/am.11.3.265-267.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberton A. M., Wolfe R. S. Adenosine triphosphate pools in Methanobacterium. J Bacteriol. 1970 Apr;102(1):43–51. doi: 10.1128/jb.102.1.43-51.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STADTMAN T. C., BARKER H. A. Studies on the methane fermentation. IX. The origin of methane in the acetate and methanol fermentations by methanosarcina. J Bacteriol. 1951 Jan;61(1):81–86. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.1.81-86.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman T. C. Methane fermentation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1967;21:121–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.21.100167.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLIN E. A., WOLIN M. J., WOLFE R. S. FORMATION OF METHANE BY BACTERIAL EXTRACTS. J Biol Chem. 1963 Aug;238:2882–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto I., Ishimoto M. Anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli on formate by reduction of nitrate, fumarate, and trimethylamine N-oxide. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1977;17(3):235–242. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3630170309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeikus J. G. The biology of methanogenic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977 Jun;41(2):514–541. doi: 10.1128/br.41.2.514-541.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhilina T. N., Zavarzin G. A. Troficheskie sviazi metanosartsinoi i ee sputnikami. Mikrobiologiia. 1973 Mar-Apr;42(2):266–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinder S. H., Brock T. D. Methane, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide production from the terminal methiol group of methionine by anaerobic lake sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Feb;35(2):344–352. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.344-352.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]