ABSTRACT

Low health literacy contributes significantly to cancer health disparities disadvantaging minorities and the medically underserved. Immigrants to the United States constitute a particularly vulnerable subgroup of the medically underserved, and because many are non-native English speakers, they are pre-disposed to encounter language and literacy barriers across the cancer continuum. Healthy Eating for Life (HE4L) is an English as a second language (ESL) curriculum designed to teach English language and health literacy while promoting fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention. This article describes the rationale, design, and content of HE4L. HE4L is a content-based adult ESL curriculum grounded in the health action process approach to behavior change. The curriculum package includes a soap opera-like storyline, an interactive student workbook, a teacher's manual, and audio files. HE4L is the first teacher-administered, multimedia nutrition–education curriculum designed to reduce cancer risk among beginning-level ESL students. HE4L is unique because it combines adult ESL principles, health education content, and behavioral theory. HE4L provides a case study of how evidence-based, health promotion practices can be implemented into real-life settings and serves as a timely, useful, and accessible nutrition–education resource for health educators.

KEYWORDS: Health literacy, Immigrants, Cancer health disparities, English as a second language, Intervention

HEALTHY EATING FOR LIFE: RATIONALE AND DEVELOPMENT OF AN ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE (ESL) CURRICULUM FOR PROMOTING HEALTHY NUTRITION

Healthy Eating for Life (HE4L) is a teacher-administered, English as a second language (ESL) curriculum intervention designed to promote healthy eating for cancer prevention while improving English language skills and health literacy. HE4L is designed for beginning-level ESL classrooms that serve predominantly medically underserved, limited literacy, immigrant populations. This article presents the background and rationale behind HE4L and describes the design and content of the curriculum. Our goal is to demonstrate how evidence-based practices can be incorporated into a real-life context where they have the potential to impact a population in need of effective cancer prevention interventions.

Cancer health disparities

Cancer health disparities are “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of cancer and related adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups [1].” Lack of health care coverage and low socioeconomic status are the two primary factors that contribute to cancer health disparities in the United States [2]. Cancer health disparities may be explained further by limitations in both general literacy and health literacy among individuals from the most marginalized populations [3].

Individuals from ethnic minority and medically-underserved populations are disproportionately affected by cancer health disparities in that they have a higher risk of being diagnosed and dying from cancers that are preventable, generally curable, or both; tend not to engage in cancer screening behaviors and thus are diagnosed at later stages of the disease; receive inadequate or no treatment; and suffer from cancer without palliative care [4]. Immigrants to the US constitute one particularly vulnerable medically-underserved group. In 2010, immigrants represented 13 million (26 %) of the 49.9 million uninsured and were 2.5 times more likely to be uninsured than US citizens [5]. As many immigrants are non-native English speakers, they are particularly hard to reach for intervention purposes because they are pre-disposed to encounter language and literacy barriers.

One way to address cancer health disparities, then, is by improving health literacy (i.e., “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [6]). Low health literacy results in less disease knowledge, low use of screening and prevention behaviors, and poor health maintenance and outcomes [7–9]. Despite the strong evidence linking low health literacy to poor health outcomes, few health literacy interventions exist to address health disparities [10].

Health literacy and cancer health disparities

Low health literacy poses a significant public health challenge for some minority groups including those with a low socioeconomic status and the medically underserved. Individuals in the two lowest English literacy levels are more likely to be poor and members of a minority population (i.e., Hispanic, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaskan Native) [11]. Additionally, more than one third (36 %) of adults have only “basic” or “below basic” health literacy, and Hispanics have the lowest average health literacy of all other racial/ethnic groups [12].

Low health literacy contributes significantly to the cancer health disparities experienced by minorities and the medically underserved. In terms of cancer prevention knowledge, low health literacy is associated with poor knowledge about mammography screening among a low-income, low-literacy sample [13]. In fact, health literacy may be a better predictor of cervical cancer screening knowledge than either education or ethnicity. For example, individuals with high health literacy are twice as likely as those with low health literacy to have acceptable knowledge of facts about cervical cancer screening [14]. Further, the odds of not having had a mammogram in the past 2 years were 1.5 times greater, and the odds of not having had a Pap test were 1.7 times greater for Medicare enrollees with low health literacy compared to those with high health literacy [15]. Regarding cancer diagnosis, one study found that the odds of presenting with late stage prostate cancer were 1.6 times greater among those with low health literacy compared to those with high health literacy [16].

The intervention setting and curriculum topic

To address findings that insufficient education contributes to low health literacy [11], guidelines for integrating health literacy concepts into adult basic education (ABE) curricula have been established [17]. One ABE offering, adult ESL courses, is distinct in that it also targets vulnerable immigrant and minority populations. Thus, we selected ESL courses as an appropriate and promising venue for addressing cancer health disparities.

We conducted formative research to determine the feasibility of this approach and to identify the overarching topic for the curriculum [18]. The results of focus groups and interviews with ESL students and other key informants indicated that teaching health literacy concepts via the ESL curriculum was feasible and also that ESL classrooms were an attractive setting for such an intervention because the students were highly motivated to attend class [18]. We identified a strong body of evidence linking reduced cancer risk to healthy behaviors such as avoiding tobacco, eating a healthy diet, and engaging in physical activity [19]. We chose healthy eating as the curriculum topic over other cancer prevention behaviors based on both pilot data of students' preferences and on its potential to inspire universally appealing, interesting, and interactive curricular materials. Although numerous community-based interventions have been conducted to reduce cancer risk [20–24], such interventions typically have not been conducted in ESL classrooms, where teaching the vocabulary and other language skills related to these behaviors in itself enhances adults' ability to understand basic health information (i.e., one component of health literacy). We identified only one example in the literature where the ESL setting was used to conduct a teacher-administered nutrition intervention, in this case for cardiovascular disease prevention [25]. To our knowledge, HE4L is the first teacher-administered, multimedia nutrition–education curriculum designed specifically for beginning-level adult ESL students to reduce cancer risk.

METHOD

Curriculum design

HE4L was designed as a content-based, adult ESL curriculum with a primary focus on encouraging fruit and vegetable consumption. Content-based second language instruction is defined as the integration of language teaching goals with specific content [26]. One approach to content-based instruction is a “theme-based” teaching model which first organizes instruction around a theme or topic and then around language learning topics [26] and is the primary model applied to adults with limited second-language skills [27]. This approach teaches listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills by exposing students to the English language in an authentic and interactive environment. We chose to use the theme-based approach given our primary focus on increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. The curriculum also is grounded in national and local adult English language learning (ELL) frameworks [28] and the health action process approach (HAPA) theory of behavior change [29].

Goals and objectives

Working with two experts in adult ESL, we developed an interactive, nutrition-focused curriculum for beginning-level students (i.e., students with very limited English language skills). The curriculum goals were threefold: (a) provide adult ESL students with the opportunity to learn the language and literacy skills that will help them to maintain a healthy diet and lifestyle, (b) help students identify and develop planning skills for making healthy lifestyle choices and for managing setbacks, and (c) encourage students to identify, use, and celebrate healthy aspects of multiple cultures. We specified three curriculum objectives to operationalize these goals: (a) improve students' scores on the test that assesses adult learning and literacy, the Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment System (CASAS), (b) help students understand basic nutrition information using an interactive and engaging format, and (c) encourage the students to engage in interactive learning activities that require them to draw on their own experiences. Each unit of HE4L contained English language and health learning objectives.

Guiding theory

The behavior change component of HE4L was based on the HAPA which has been used in various studies of dietary behaviors to demonstrate that certain social–cognitive constructs (e.g., intentions, self-efficacy, risk perceptions, outcome expectancies) and intermediary behaviors (e.g., action and coping planning) can influence diet behaviors [29–34]. The HAPA posits that action and coping planning are the proximal antecedents to behavior change and that these constructs bridge the gap between intentions and behavior [29]. Together with self-efficacy and intentions, these planning behaviors change or mediate the relationship between risk perception and outcome expectancies and self-reported nutrition behavior [30–33]. Numerous activities in the curriculum are designed to focus on action and coping planning skills with regards to eating more fruits and vegetables. For example, in one lesson, students plan meals and snacks using foods from each of the food groups in the food pyramid (e.g., fruits, vegetables, whole grains; please note this curriculum was written prior to the release of the United States Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) MyPlate). After students prepare their meal plans, they discuss the plans with their classmates. The purpose of teaching students this type of action planning is to help them to be more prepared to engage in behaviors that lead to healthy eating (e.g., shopping for healthy ingredients).

Competencies and standards

The curriculum content is informed by the life skill competencies specified by CASAS as being essential for adults to be functional members of society [35]. Field-tested and regularly updated and validated at the state and national level, the CASAS competencies are used widely in adult education [36]. The competencies also address student needs as well as national- and state-level standards [36]. They are assessed through a series of listening, speaking, reading, and writing tests that Connecticut adult ESL students are required to take at the beginning of the semester and again once they have completed at least 40 h of instruction. Table 1 provides a list of the 23 CASAS competencies addressed through HE4L.

Table 1.

CASAS competencies addressed in HE4L

| Number | Description | Percent (number) of related lessons |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1.2 | Understand or use appropriate language in general social situations (e.g., to greet, introduce, thank, apologize) | 9.1 % (1/11) |

| 0.1.5 | Interact effectively in the classroom | 100 % (11/11) |

| 0.1.7 | Understand, follow, or give instructions, including commands and polite requests (e.g., Do this; Will you do this?) | 100 % (11/11) |

| 0.1.8 | Understand or use appropriate language to express emotions and states of being (e.g., happy, hungry, upset) | 81.8 % (9/11) |

| 0.2.1 | Respond appropriately to common personal information questions | 81.8 % (9/11) |

| 0.2.3 | Interpret or write a personal note, invitation, or letter | 18.2 % (2/11) |

| 0.2.4 | Converse about daily and leisure activities and personal interests | 36.4 % (4/11) |

| 1.1.1 | Interpret recipes | 45.5 % (5/11) |

| 1.3.5 | Use coupons to purchase goods and services | 27.5 % (3/11) |

| 1.6.1 | Interpret food packaging labels such as expiration dates | 18.2 % (2/11) |

| 2.1.2 | Identify emergency numbers and place emergency calls | 9.1 % (1/11) |

| 2.7.2 | Interpret information about ethnic groups, cultural groups, and language groups | 100 % (11/11) |

| 3.1.3 | Identify and use health care services and facilities, including interacting with staff | 36.4 % (4/11) |

| 3.1.6 | Interpret information about health care plans, insurance, and benefits | 18.2 % (2/11) |

| 3.2.1 | Fill out medical health history forms | 18.2 % (2/11) |

| 3.2.3 | Interpret forms associated with health insurance | 18.2 % (2/11) |

| 3.5.1 | Interpret information about nutrition, including food labels | 100 % (11/11) |

| 3.5.2 | Identify a healthy diet | 100 % (11/11) |

| 3.5.9 | Identify practices that help maintain good health such as regular checkups, exercise, and disease prevention measures | 100 % (11/11) |

| 3.6.3 | Interpret information about illnesses, diseases, and health conditions, and their symptoms | 36.4 % (4/11) |

| 3.6.4 | Communicate with a doctor or medical staff regarding condition, diagnosis, treatment, concerns, etc., including clarifying instructions | 27.5 % (3/11) |

| 6.0.1 | Identify and classify numeric symbols | 36.4 % (4/11) |

| 6.0.2 | Count and associate numbers with quantities, including recognizing correct number sequencing | 54.5 % (6/11) |

Teacher training

The curriculum includes a 1-day intensive teacher training. The purpose of the training is to ensure that the teachers are comfortable using the curriculum materials and to demonstrate that the curriculum can work with different teaching and learning styles and with students at varying levels of beginning-level English. Participants are exposed to the foundations of the curriculum such as the CASAS competencies and the theoretical background of the materials; however, the majority of the training is devoted to experiential learning. The teachers use the exercises, activities, audio files, and video to practice using the curriculum with their peers. They are also asked to provide examples of how they would use the materials in their classrooms and with students at varying levels of beginning-level instruction. Finally, they are introduced to the curriculum website which serves as a forum for teachers to discuss their curriculum implementation experiences, access additional curriculum resources, and post examples of modified activities they used successfully in their classrooms.

Material design

Our goal was to create a curriculum that was useful, timely, and accessible to teachers and students. Adult ESL classrooms are dynamic in that teachers teach to the needs of their students rather than following a set curriculum each semester. For example, if students are interested in learning English language skills for finding employment, the ESL teacher will generate lessons around this topic. As a result, we designed the curriculum so that it could be used in whole or in parts [18].

The HE4L curriculum package includes a soap opera- or telenovela-like storyline presented in DVD format, an interactive student workbook, a teacher's manual, and audio files available on CD. HE4L's multimedia components address the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) recommendations for including audio, video, and computer technology in addition to print when delivering an intervention [37]. Curriculum content addresses all aspects of literacy–reading, listening, speaking, writing, and numeracy–that the IOM has identified as essential for interventions targeting health literacy [37]. The next sections describe each component of HE4L.

Telenovela

The telenovela storyline is the thread that ties each of the components together. The materials in the workbook reflect what is happening in the story. Told in a video format, telenovelas have long been used in behavioral interventions with the Hispanic community as a means to communicate health-promotion messages through a popular culture medium [38]. Narrative approaches to health communication may be especially effective when targeting populations with strong oral history traditions, like African-Americans and Hispanics [39]. The six-episode telenovela, “Ana's Kitchen,” tells the story of an immigrant family from Costa Rica on their journey to a healthier diet. One member of the family has health problems due in part to an unhealthy lifestyle the family developed upon emigrating to the US. Doctor's orders dictate that the family must learn healthier eating and lifestyle habits. The Ana's Kitchen DVD was filmed locally, in English, using Latino actors.

Workbook

The content of the student workbook addresses a set of ELL and health literacy objectives. The workbook includes four units, each with three lessons (except for unit 4, which has two). Table 2 provides the ELL and health learning objectives for unit 1. The learning objectives for the other four units are available from the authors.

Table 2.

HE4L unit 1 objectives and health messages

| ELL objectives | Health objectives | Health messages |

|---|---|---|

| Lesson 1.1: family and food | ||

| 1. You will identify the correct form of the verb “to be.” | 1. You will recognize opportunities in your everyday life to eat healthier. | 1. Ernesto's advice: we can avoid feeling tired if we eat more healthy foods. |

| 2. You will use subject pronouns. | 2. Abuelita's advice: exercise can give you confidence and more energy. | |

| 3. You will apply correct forms of contractions with subjects and the verb “to be.” | ||

| Lesson 1.2: food where we live | ||

| 1. You will use the verb “to be” with adjectives. | 1. You will compare your eating habits from your home country to your eating habits here. | 1. David's advice: to avoid eating too much fat, bake your chicken don't fry it. |

| 2. You will apply negative statements to the verb “to be.” | 2. Pepita's advice: we can take better care of ourselves by eating more fruits and vegetables. | |

| Lesson 1.3: living healthier | ||

| 1. You will use yes/no questions with the verb “to be.” | 1. You will learn to plan to eat healthier. | 1. Abuelita's advice: we can avoid feeling tired if we eat healthier. |

| 2. Pepita's advice: we can take better care of ourselves by eating more fruits and vegetables. | ||

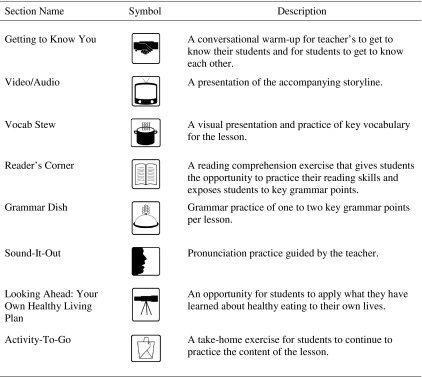

Each lesson is comprised of activities focusing on different aspects of literacy (e.g., listening, vocabulary, reading, grammar, pronunciation). Visual cues are used throughout the workbook to help students understand key concepts, vocabulary [40], and the organizational strategy of the workbook (see Table 3 for a list and description of the primary visual cues).

Table 3.

Healthy Eating for Life lesson sections and symbols

Each lesson also contains two key health messages. The messages were designed to enhance and reinforce the idea that a healthy lifestyle (e.g., eating more fruits and vegetables and exercising) promotes health in many ways. Messages were designed using a well-established message development paradigm that has been tested in previous research [41, 42]. For each message, a photograph of a character from Ana's Kitchen is accompanied by one to two sentences of “advice.” For example, Pepita's advice is: “We can take better care of ourselves by eating more fruits and vegetables.” Table 2 includes additional examples.

There are five main categories of health activities necessary for achieving health literacy [43]. These categories informed the four units in the HE4L curriculum: health promotion (enhance and maintain health), health protection (safeguard health), disease prevention (regular checkups and disease screening), health care and maintenance (seeking care and establishing relationships with providers), and systems navigation (access to services and understanding patient rights) [43]. These categories naturally overlap and provide a comprehensive spectrum of activities necessary to achieve health literacy.

Unit 1, “Your Lifestyle and Your Health,” focuses on health promotion and how students' lifestyles can affect their health. It includes lessons that discuss family and food, activities in which students compare their diet in the US to their diet in their home country, and exercises in which students generate ideas for living more healthily. For example, a reading comprehension exercise asks students to read a short paragraph entitled, “Food from Home,” wherein one of the main characters talks about all of the healthy foods in her home country. Students then circle all of the words they do not know and write down three foods they miss from their home countries.

Unit 2, “Navigating the Health System,” touches on disease prevention, health care and maintenance, and systems navigation. This unit helps students to acquire some of the knowledge and skills necessary to interact effectively with the health system. Students engage in exercises and activities related to getting to the doctor, talking to the doctor, and following through with the doctor's recommendations. For example, using newly acquired vocabulary, a student is asked to role-play a symptom that would prompt a call to the doctor or a symptom that would require a visit to the emergency room. Other students in the class shout out which symptom their fellow student is acting out and then use a complete sentence to state whether the student should go to the doctor or the emergency room.

Unit 3, “A Balanced Diet,” focuses on health protection and disease prevention and discusses how to create a balanced diet by teaching students the English language skills needed to navigate the grocery store and the kitchen, and to prepare healthy meals. For example, students are provided with pictures and a list of fruits or vegetables in a given color category (e.g., yellow: summer squash, yellow bell peppers). They are asked to list in English other yellow foods and then write a brief sentence using the imperative that explains how to use the food (e.g., pineapple: grill pineapple rings. Place on top of turkey burger for topping).

Unit 4, “Celebrations!” focuses on health promotion and celebrating good health and family. For example, students plan a dinner party with healthy dishes from their home countries. They also make plans to maintain these healthy behaviors in the future.

Teacher's manual

The teacher's manual follows the same format as the student workbook and also contains helpful hints in the form of “teacher's memos.” The teacher's memos contain suggestions for making certain activities and exercises harder or easier, instructions for conducting interactive classroom activities based on lesson content, and suggestions for additional activities to do with students.

Audio files

The audio files supplement the workbook and mirror the content of both the workbook and the telenovela. The audio files, available to teachers in CD format, provide additional listening, speaking, and pronunciation practice. The integrated skills approach stresses the importance of listening and pronunciation practice using relevant, real-world examples and scenarios [27]. Each lesson has an accompanying audio file that reviews the key health messages in the lesson, reviews the corresponding point in the plot of Ana's Kitchen, includes a verbal presentation of the reading comprehension exercise, and walks students through the pronunciation practice. The audio files range in duration from 4 to 11 min.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the article was to demonstrate how evidence-based practices can be incorporated into a real-life context where they have the potential to impact a population in need of effective cancer-prevention interventions. The HE4L curriculum was designed to teach English and health literacy to low-literate, non-native English-speaking adults who are members of a population, according to national surveys, that is at increased risk of suffering from cancer health disparities [4]. HE4L is the first teacher-administered, multimedia nutrition–education curriculum designed to reduce cancer risk among beginning-level ESL students. HE4L also is the first nutrition curriculum for ESL students to integrate and apply the HAPA model of behavior change theory into the design of its curriculum materials. The HAPA model is unique in that it goes beyond knowledge acquisition in developing students' action and coping planning skills [29]. Teaching these skills and testing for their impact constitute a novel approach to behavior change theory.

HE4L is timely in that cancer health disparities persist, and innovative approaches to prevention and control are needed. In contrast to previous intervention efforts, HE4L was designed to reach a multiethnic sample of the medically underserved as opposed to a specific racial or ethnic group. Additionally, because HE4L focuses on the broad topic of healthy eating, which plays a prominent role in chronic disease etiology, its reach may extend beyond cancer prevention to the prevention of chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. Finally, HE4L utilizes an innovative venue (the ESL classroom) and employs multiple delivery modules (workbooks, video, and audio files) in order to maximize effectiveness.

There are some limitations to HE4L that should be noted. First, HE4L was conceived as a way to reach a multiethnic sample of adult ESL students, but some elements of the curriculum may be more relevant to specific students. For example, the telenovela component of the curriculum contains universal elements such as a focus on family relationships, celebrations, cooking, and eating, but Latino actors were used and Hispanic culture is the focus. Thus, Ana's Kitchen may be most relatable for Hispanic students. Second, the purpose of HE4L was to reach medically-underserved adults who have low health-literacy levels and who are at greater risk for cancer. Adults who enroll in and attend ESL courses may not represent this population; thus, it may not reach those adults who are most in need. However, adult ESL students may play an important role in the behaviors and attitudes of this population or within their own households, or both, which may offer benefits to the larger population. Third, HE4L requires that teachers are trained in delivering and using the curriculum as it was intended to be used. Teachers are well placed to deliver the intervention given their relationships with the students and knowledge of the teaching methods unique to ESL; however, if teachers are not trained appropriately, choosing a teacher-administered format can result in variability of dosage, commitment, and accuracy in delivering the material.

HE4L has undergone pilot testing in adult ESL classrooms. The results of the tests of HE4L are presented elsewhere [44]. Key outcomes of interest include knowledge of a healthy diet, fruit and vegetable consumption, action and coping planning skills, and adult literacy scores in the form of reading and listening scores from the statewide CASAS standardized tests. Future directions for HE4L could include expanding the curriculum for use in additional adult basic education settings such as pre-GED, high school credit diploma programs, and family literacy programs. The curriculum also could be adapted to include units on other cancer prevention behaviors like regular exercise.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH EDUCATION PRACTICE

The multidisciplinary nature of the HE4L curriculum and its solid foundation in health behavior theory and adult education principles makes it a promising curriculum and nutrition–education tool for health educators and ESL teachers. The curriculum development process described in this article addresses several of the competencies for health education specialists [45]. The competencies reflect the professional responsibilities of health educators and fall under the following categories: needs and capacity assessment, program planning, implementation, evaluation and research, administration and management, and communication and advocacy. The development and piloting of HE4L encompassed several of these competency areas.

The formative phase of HE4L was designed to assess the health education needs of the students and the capacity of local organizations to implement an intervention [18]. The formative findings were used during the planning phase to narrow the curriculum topic and scope to nutrition education for cancer prevention among beginning-level ESL students. Curriculum goals and objectives were designed to address beginning-level ESL students' English language and nutrition learning needs and were guided by adult education theory and English language instruction principles. The HAPA was chosen during the planning phase as the theoretical foundation of the curriculum. Specific activities related to action and coping planning were developed to translate health behavior theory to practice. Curriculum implementation was a collaborative effort between the State Department of Education, local adult education organizations, program administrators, teachers, and researchers. Research needs were adapted to work in concert with programmatic needs to ensure the best outcomes for students and teachers. Balancing the needs of key stakeholders was an important part of the curriculum planning and implementation processes. Curriculum monitoring and evaluation included qualitative and quantitative components, and all research activities were conducted in collaboration with our community partners. Research outcomes are reported elsewhere [44], and evaluation results are forthcoming. The HE4L curriculum continues to serve as a nutrition–education resource to the ESL teachers who were involved in its implementation and evaluation. In summary, the HE4L curriculum development process is reflective of the professional competencies and responsibilities specific to health education practice. Future iterations of HE4L can successfully be adapted to suit the needs and capacity of students and organizations interested in using the curriculum, without deviating from the goal of informing and improving health education practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sigrid “Siggy” Nystrom and Erica Gordon for their creativity, enthusiasm, and commitment to the HE4L project. Further, the authors would like to thank Maureen Wagner and Ajit Gopalakrishnan of the CT State Department of Education (Division of Educational Programs and Services, Bureau of Adult Education and Nutrition) for their partnership and support and Elizabeth Demsky and other members of the Health, Emotion, and Behavior Laboratory for their collaboration and input.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 5R01-CA068427 and 5P30-CA16359 both from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Incorporating evidence-based, health-promotion strategies into adult English as a second language curriculum can be a timely, useful, and accessible mean to impact a population in need of effective cancer prevention interventions.

Policy: The information gleaned from testing the effectiveness of HE4L can be used to inform state- and national-level health education policies. Incorporating evidence-based health promotion strategies into pre-existing services, such as adult education, can ensure that important health information and behavioral skills are disseminated to at-risk populations.

Research: Testing health education interventions in the adult education setting may help researchers gain access to marginalized populations. Because adults enrolled in English as a second language classes are highly motivated to attend class (to become proficient in English), study attrition may be reduced.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Health disparities defined. http://crchd.cancer.gov/disparities/defined.html. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 2.National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Institute fact sheet: cancer health disparities questions and answers. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/cancer-health-disparities/disparities. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 3.Parker RM, Ratzan SC, Lurle N. Health literacy: a policy challenge for advancing high quality health care. Heal Aff. 2003;22:147–153. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.4.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Report of the trans-HHS cancer health disparities progress review group: making cancer health disparities history. http://www.hhs.gov/chdprg/pdf/chdprg.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2011.

- 5.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports: Consumer Income. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office; 2011. pp. 60–239. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: health literacy overview. http://nnlm.gov/outreach/consumer/hlthlit.html. Accessed May 4, 2011.

- 7.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1278–1283. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy and the risk of hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:867–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, et al. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities. J Health Commun. 2010;15:34–41. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudd RE, Colton T, Schacht R. An overview of medical and public health literature addressing literacy issues: an annotated bibliography. The National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy (NCSALL). NCSALL Reports #14. http://www.ncsall.net/fileadmin/resources/research/report14.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 12.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006–483). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis TC, Arnold C, Berkel HJ, et al. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996;78:1912–1920. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961101)78:9<1912::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindau ST, Tomori C, Lyons T, et al. The association of health literacy with cervical cancer prevention knowledge and health behaviors in a multiethnic cohort of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:938–943. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams M, et al. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3101–3104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soricone L, Rudd R, Santos M, et al. Health literacy in adult basic education: designing lessons, units, and evaluation plans for an integrated curriculum. 2007; http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy/files/healthliteracyinadulteducation.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 18.Martinez JL, Rivers SE, Latimer AE, et al. Formative research for a community based message framing intervention. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36:335–347. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.3.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Cancer Society. The importance of behavior in cancer prevention and early detection. n.d. http://www.cancer.org/Research/ResearchProgramsFunding/BehavioralResearchCenter/TheImportanceofBehaviorinCancerPreventionandEarlyDetection/index. Accessed March 15, 2011.

- 20.Havas S, Heimendinger J, Damron D, et al. 5 a day for better health – nine community research projects to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:68–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, et al. Healthy Body/Healthy Spirit: a church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:562–573. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarro AM, Rock CL, McNicholas LJ, et al. Community-based education in nutrition and cancer: the Por La Vida Cuidándome curriculum. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15:168–172. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potter JD, Graves KL, Finnegan JR, et al. The cancer and diet intervention project: a community-based intervention to reduce nutrition-related cancer risk. Health Educ Res. 1990;5:489–503. doi: 10.1093/her/5.4.489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciliska D, Miles E, O’Brien MA, et al. Effectiveness of community-based interventions to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2000;32:341–352. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(00)70594-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elder JP, Candelaria JI, Woodruff SI, et al. Results of language for health: cardiovascular disease nutrition education for Latino English-as-a-second language students. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:50–63. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinton DM, Snow MA, Wesche MB. Content-based second language instruction – Michigan classics edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oxford R. Integrated skills in the ESL classroom. ESL Mag. 2001;6:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connecticut State Department of Education. Connecticut State Department of Education English Language Learner Framework. Bureau of Health/Nutrition, Family Services and Adult Education. n.d. www.sde.ct.gov/curriculum/language_arts/framework/englishlanguagelearnerframeworks2005%20.doc - 2005-11-29. Accessed February 23, 2011.

- 29.Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 2008;57:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholz U, Nagy G, Gohner W, et al. Changes in self-regulatory cognitions as predictors of changes in smoking and nutrition behaviour. Psychol Heal. 2009;24:545–561. doi: 10.1080/08870440801902519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renner B, Kwon S, Yang BH, et al. Social-cognitive predictors of dietary behaviors in South Korean men and women. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:4–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03003068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzer R, Renner B. Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: action self-efficacy and coping self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2000;19:487–495. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarzer R, Schüz B, Ziegelmann JP, et al. Adoption and maintenance of four health behaviors: theory-guided longitudinal studies on dental flossing, seat belt use, dietary behavior, and physical activity. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:156–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02879897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarzer R, Sniehotta FF, Lippke S, et al. On the assessment and analysis of variables in the Health Action Process Approach: conducting an investigation. Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin. http://web.fu-berlin.de/gesund/hapa_web.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 35.Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment System (CASAS). CASAS competencies: essential life and work skills for youth and adults. http://www.casas.org/docs/pagecontents/casascompetenciesmay2008finalv1.pdf?Status=Master. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 36.Connecticut State Department of Education. Connecticut Competency System (CCS) assessment policies and guidelines: fiscal year 2010-2011. Bureau of Health/Nutrition, Family Services and Adult Education. http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/lib/sde/PDF/DEPS/Adult/accountability/ccspolicies.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2011.

- 37.Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alcalay R, Alvarado M, Balcazar H, et al. Salúd para su corazón: a community-based latino cardiovascular disease prevention and outreach model. J Community Health. 1999;24:359–379. doi: 10.1023/A:1018734303968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2006;34:777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canning-Wilson C. Using pictures in EFL and ESL classrooms. Paper presented at: Current Trends in English Language Testing Conference (ERIC Document Reproductive Service No. ED445526); June 1999; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

- 41.Latimer AE, Williams-Piehota P, Katulak NA, et al. Promoting fruit and vegetable intake through messages tailored to individual differences in regulatory focus. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latimer AE, Rench T, Rivers SE, et al. Promoting participation in physical activity using framed messages: an application of prospect theory. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13:659–681. doi: 10.1348/135910707X246186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudd RE, Kirsch I, Yamamoto K. Literacy and health in America: policy information report. Princeton NJ: Educational Testing Services. http://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/PICHEATH.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2011.

- 44.Duncan LR, Martinez JL, Rivers SE, et al. Healthy eating for life English as a second language curriculum: primary outcomes from a nutrition education intervention targeting cancer risk reduction. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(7):950–961. doi: 10.1177/1359105312457803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Commission for Health Education Credentialing. Areas of responsibility for health education specialists. http://www.nchec.org/_files/_items/nch-mr-tab3-110/docs/areas%20of%20responsibilities%20competencies%20and%20sub-competencies%20for%20the%20health%20education%20specialist%202010.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2012.