Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Severe, drug-resistant gastroparesis is a debilitating condition. Several, but not all, patients can get significant relief from nausea and vomiting by gastric electrical stimulation (GES). A trial of temporary, endoscopically delivered GES may be of predictive value to select patients for laparoscopic-implantation of a permanent GES device.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We conducted a clinical audit of consecutive gastroparesis patients, who had been selected for GES, from May 2008 to January 2012. Delayed gastric emptying was diagnosed by scintigraphy of ≥50% global improvement in symptom-severity and well-being was a good response.

RESULTS:

There were 71 patients (51 women, 72%) with a median age of 42 years (range: 14-69). The aetiology of gastroparesis was idiopathic (43 patients, 61%), diabetes (15, 21%), or post-surgical (anti-reflux surgery, 6 patients; Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 3; subtotal gastrectomy, 1; cardiomyotomy, 1; other gastric surgery, 2) (18%). At presentation, oral nutrition was supplemented by naso-jejunal tube feeding in 7 patients, surgical jejunostomy in 8, or parenterally in 1 (total 16 patients; 22%). Previous intervention included endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin (botox) into the pylorus in 16 patients (22%), pyloroplasty in 2, distal gastrectomy in 1, and gastrojejunostomy in 1. It was decided to directly proceed with permanent GES in 4 patients. Of the remaining, 51 patients have currently completed a trial of temporary stimulation and 39 (77%) had a good response and were selected for permanent GES, which has been completed in 35 patients. Outcome data are currently available for 31 patients (idiopathic, 21 patients; diabetes, 3; post-surgical, 7) with a median follow-up period of 10 months (1-28); 22 patients (71%) had a good response to permanent GES, these included 14 (68%) with idiopathic, 5 (71%) with post-surgical, and remaining 3 with diabetic gastroparesis.

CONCLUSIONS:

Overall, 71% of well-selected patients with intractable gastroparesis had good response to permanent GES at follow-up of up to 2 years.

Keywords: Delay, enterra, functional dyspepsia, gastric-emptying

INTRODUCTION

Gastroparesis is chronic, delayed emptying of the stomach in the absence of any mechanical obstruction.[1] In clinically severe manifestation, gastroparesis can produce continuous nausea and frequent vomiting, resulting in malnutrition, dehydration, and increased risk of thrombosis.[2,3] Pharmacotherapy is limited to prokinetic medications such domperidone, metoclopramide, itopride, and erythromycin. Endoscopic intervention such as injection of botulinum toxin into the pylorus is of inconsistent benefit.[4,5] Near-total gastrectomy is the only surgical option that has been reported to be of some value in small case-series.[6]

High-frequency and low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) using the Enterra™ system (Medtronics, Minnesota, USA) was granted “humanitarian device exemption” status,[7] by the Food and Drug Administration, USA, in 2000, for use in patients with drug-resistant, severe gastroparesis. In the UK, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence issued Interventional Procedure Guidance for GES in 2004.[8] GES involves surgical (usually laparoscopic) implantation of two stimulating electrodes on the gastric antrum and connection of these electrodes to a subcutaneously placed pulse generator in the anterior abdominal wall. Enterra™ therapy can result in significant improvement or even total resolution of nausea and vomiting, with enormous improvement in the quality of life.[9] However, some patients have inexplicably poor response. Since GES is expensive and involves surgical intervention, pre-operative identification of patients of those that are likely to respond best to GES is an important clinical goal. Ayinala et al.,[10] first reported the use of a temporary, endoscopically placed electrode to deliver mucosal GES and selected only those patients who had clinically meaningful response (>50% symptom-improvement) for surgical implantation of permanent GES. Surprisingly, there have been few subsequent reports on this selection strategy.[11,12,13]

We started our practice of GES with a policy to routinely use temporary, endoscopic GES to select patients for laparoscopic implantation of permanent GES. We audited our practice to evaluate the outcome of short-term, symptom improvement with permanent GES.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We started the practice of GES with Enterra™ (Medtronics, USA) in our centre, a university hospital in the north of England in May 2008. The present study is a clinical audit comprising of consecutive patients and follow-up data upto January 2012. A prospective database was maintained since inception and was supplemented by retrospective review of case-notes. The service was started by one upper gastrointestinal surgeon (SD), who was joined by another (AS), anda formal gastroparesis multi-disciplinary team (MDT) has been formed and comprises of the two surgeons, a gastroenterologist, a radiologist with expertise in nuclear medicine imaging, a chronic pain physician, a clinical pharmacist, and a MDT co-ordinator. There is close liaison with the Dietetics and Nutrition Department.

With increasing awareness of gastroparesis and of our service, patients were referred by other upper gastrointestinal surgeons, gastroenterologists and physicians from our own hospital as well as from other hospitals within the county of Yorkshire and nationwide. Most patients had been investigated extensively prior to referral; reports of endoscopies and radiological investigations were obtained from the referring physicians. At a minimum, a recent endoscopy was required to exclude mechanical gastric obstruction. Delayed gastric emptying was diagnosed by a gastric emptying scintigram. In most cases, the scintigram had been performed prior to referral to our team, often at another hospital. As such, we did not have information regarding the scintigram protocols and there were variations in the duration of imaging and reporting of quantitative data in terms of half-time of emptying or percentage retention or emptying of radioactivity at different time-points during the study. Wherever possible, the scintigram data were electronically obtained from the referring centre and reviewed by our nuclear medicine radiologist. In case of doubt, the scintigram was repeated in our centre, using a standardized protocol. Due to funding limitations and practical issues, it was not possible to repeat a scintigram for all patients. However, we confirmed a definite delay in solid-emptying from the stomach in all cases.

All patients were initially seen and evaluated in the outpatient clinic by either one of two surgeons (SD or AS). The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) was used for nutritional assessment. Symptoms of gastroparesis — nausea, vomiting, bloating, abdominal pain, and fullness after meals — were evaluated in detail and severity was recorded in a semi-objective fashion. In particular, attention was paid to overall disease severity indicated by unresponsiveness to prokinetic medication, frequency of vomiting, attendance at Accident and Emergency Departments, hospitalization, need for supplementary nutrition — oral or jejunal — and difficulty to control blood glucose in case of diabetes. Patients were selected for a trial of temporary GES if gastroparesis was deemed to be clinically severe and unresponsive to standard medical therapy. Patients with abdominal pain as the predominant symptom and need for high-dose opiate analgesia were generally excluded.

Temporary GES was done by endoscopic placement of an electrode (Transvenous Cardiac Pacing Wire, product code 6416-200, Medtronics) at the junction of the gastric body and antrum. The electrode was anchored to the mucosa by endoscopic clips, as previously described by Ayinala et al. The electrode was routed transnasally, attached to the Enterra™ pulse generator (which was carried externally by the patient), and standard stimulation parameters were applied (impedance: 200-800 Ω; current: 5 mA; cycle time: 0.1 sec ON, 5 sec OFF). The electrode was generally retained for 7-14 days. Patients were provided with a standard, structured diary to record gastroparesis symptoms (Medtronics) during the period of tGES.

Patients with ≥50% global improvement in symptom-severity and well-being were selected for permanent GES. Two electrodes were laparoscopically implanted on the anterior wall of gastric antrum, 9-cm and 10-cm proximal to the pylorus, and mid-way between the lesser and greater curvatures. The position of the electrodes was confirmed to be extra-mucosal by intra-operative gastroscopy. The electrodes were connected to the Enterra™ pulse generator, which was implanted subcutaneously in the anterior abdominal wall. Enterra™ was turned ON immediately after implantation, with standard stimulation parameters.

Follow-up was conducted in the surgical outpatient clinic at intervals of 6 weeks to 3 months. Based on symptom-response, the Enterra™ program was adjusted using an energy algorithm, previously described by Abidi et al.[14] Change in symptoms in comparison to the baseline at the initial clinic visit was evaluated and ≥50% global improvement in symptom-severity and well-being was taken as a successful outcome from Enterra™ therapy.

RESULTS

A total of 71 patients (51 women: 72%; median age: 42 years; age range: 14-69) was selected for trial of temporary, endoscopic GES; 44 patients (62%) had idiopathic gastroparesis, 14 (20%) had diabetes, and 13 (18%) had post-surgical gastroparesis. Of the latter, 6 patients had anti-reflux surgery, 4 had Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity, 1 had cardiomyotomy, 1 had splenectomy, and 1 had unclear operative details (most likely, vagotomy for peptic ulcer). At the initial consultation, 7 patients (10%) were on naso-jejunal tube feeding, 8 patients (11%) had surgically placed jejunostomy-feeding tubes, and 1 patient received parenteral nutrition. Prior to consideration for GES, 16 patients (23%) had received endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin (Botox®) into the pylorus, 2 patients had pyloroplasty, 1 patient had antrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, and 1 patient had a loop gastrojejunostomy; none of the patients had any meaningful and sustained symptomatic benefit.

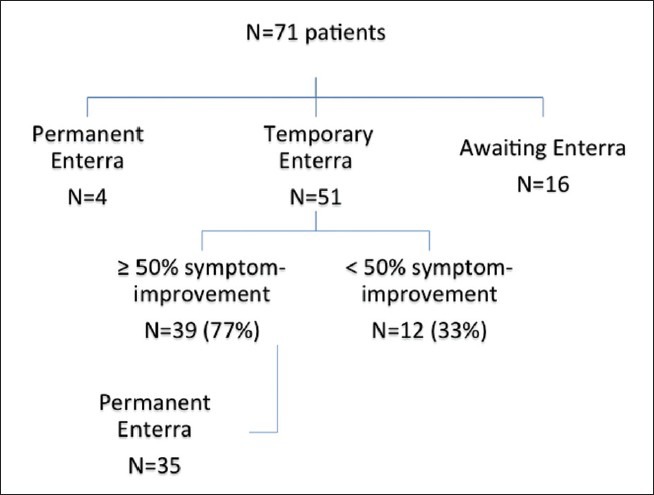

Of the 71 patients, a trial of temporary GES has been completed in 51 patients. In 4 patients, it was decided to proceed directly with permanent GES; these patients have been excluded from the present study (Figure 1). The remaining 16 patients are currently awaiting temporary GES and will be included in a future report.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of patient pathway and outcomes from temporary gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis

Of the 51 patients with temporary GES, 39 (77%) had ≥50% symptom-improvement and were selected for permanent GES, which has been completed in 35 patients. Follow-up data were available for 31 patients (idiopathic: 21; diabetic: 3; post-surgical: 7) with a median follow-up of 10 months (1–28). Twenty-two patients (71%) had ≥50% symptom-improvement. Within the individual aetiological categories, ≥50% symptom-improvement was observed in 14 patients (67%) with idiopathic gastroparesis, all 3 patients (100%) with diabetic gastroparesis, and 5 patients (71%) with post-surgical gastroparesis. For the remaining 9 patients with permanent GES and <50% benefit, we are currently persisting with program adjustment in an algorithmic fashion, with intent to achieve maximum symptom-resolution.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, permanent GES with laparoscopically implanted Enterra™ resulted in >50% symptom-improvement in 22 of 31 patients (71%) at a median follow-up of 10 months. Until date, about 7500 permanent Enterra implants have been done, worldwide (personal communication with Medtronic representative). Published data comprise two randomized clinical trials,[15,16] several case series (most with <50 patients), and two meta-analyses.[17,18] In the first randomized trial, the Worldwide Anti-Vomiting Electrical Stimulation Study, 33 patients (17: diabetic gastroparesis; 16: idiopathic gastroparesis) were randomized to an initial 2-months, double-blind phase, followed by 10-months open-label phase. At 12 months, 80% of patients reported >50% improvement in vomiting.[17] The second randomized trial was restricted to diabetic gastroparesis and comprised 55 patients, of whom 43 completed cross-over and 39 had 1 year follow-up. At 12 months, 70% of patients had >50% reduction in weekly vomiting frequency.[18] The largest series comprises of 221 patients (diabetic: 64%; idiopathic: 22%; post-surgical: 14%) with a mean follow-up of about 5 years. Fifty four percent of patients had >50% reduction in total symptom score, with the best response in diabetic group (58% of diabetics had >50% symptom reduction versus 53% of post-surgical patients versus 48% of patients in the idiopathic category).[19] None of the preceding studies used temporary, endoscopic GES as a selection criterion for surgical implantation of permanent GES.

In the present study, temporary GES resulted in ≥50% symptom-improvement in 39 of 51 patients (77%). Of those, who subsequently had permanent GES, >50% symptom-improvement was obtained in 71%. Temporary GES, using electrodes implanted onto the gastric mucosa, via endoscopy or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tracts, was initially described by Ayinala et al.,[10] As with permanent GES, a 50% symptom-improvement was used as the threshold for success. The average improvement in the total symptom score, for the entire cohort of 20 patients, was 49% with time to improvement of about 3 days, after commencing GES. For 13 patients, who had permanent GES following temporary GES, there was highly significant correlation between temporary and permanent stimulation.[10] The same group recently reported a double-blinded randomized controlled trial of temporary endoscopic mucosal GES, with an aim to demonstrate at least 50% reduction in base-line symptoms.[11] Fifty eight patients were randomized in a cross-over design to a session of temporary GES for one group, followed by the second group. The results favored stimulation, but clear differences were not demonstrated, most likely because of unexpected difficulties in the study design. A post-hoc analysis on 36 patients suggested association between response to temporary stimulation and permanent stimulation. Other authors have reported favorable response to temporary GES in 22 of 27 patients (81%).[12] Patients included in this study included those with unconventional indications for GES, such as chronic intestinal pseuodo-obstruction. Twenty of the 22 patients subsequently had permanent GES, with satisfactory symptom reduction in 90%. Thus, the present data corroborate previous reports that support the use of a trial of temporary, endoscopic GES as a tool to select patients for laparoscopic implantation of permanent GES.

There are some limitations to the present study. We did not record the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index[20] or any other objective score; we accept that objective measures are important indicators of treatment outcome, and such instruments have been included in our current, prospectively maintained database. The baseline scintigrams were not done by a common, standardized protocol, as has been recommended,[21] and an unified reporting system would have helped to better characterize our group. However, the exigencies of our healthcare system were such that repeated investigations, in the absence of an overriding clinical indication, were not permitted. We intentionally did not perform scintigrams for follow-up; previous studies have shown only weak correlation between symptom improvement and increase in gastric emptying and follow-up scintigrams do not change clinical management.[17,21] Finally, the present follow-up is short and longer-term results need to be awaited.

In conclusion, by using a strategy of temporary GES to select patients for laparoscopic implantation of a permanent Enterra™ stimulator, we obtained clinical meaningful (>50%) symptom-improvement in 71% patients with clinically severe, drug-unresponsive gastroparesis. About 3 out of 4 (77%) patients with >50% improvement by temporary GES had improvement by permanent GES: a proportion similar to that reported by others.[10,11,12] Longer-term, follow-up data are necessary and randomized trials are desirable, but have proved difficult to conduct in a condition that may occupy “orphan” disease status. A practical reality is the issue of cost. Even in a socialized healthcare system, such as the National Health Service in the UK, a detailed application for “exceptional case” funding is necessary and approval varies by case and funding authority. As such, selection tools and outcome measures gain particular relevance and case-series, such as the present one, provides helpful evidence.

Footnotes

Members of the Leeds Gastroparesis Multi-Disciplinary Team: Dr. Baranidharan, Consultant in Pain Management; Dr. Fahmid Chowdhury, Consultant Radiologist and Nuclear Medicine Physician; Dr. Mark Denyer, Consultant Gastroenterologist; Mr Simon Dexter, Consultant Surgeon; Mr. Abeezar Sarela, Consultant Surgeon; Mr. Charles Walker, Clinical Pharmacist & Ms. Helen Simpson, Gastroparesis Team Coordinator.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1592–622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkman HP, Camilleri M, Farrugia G, McCallum RW, Bharucha AE, Mayer EA, et al. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: Excerpts from the AGA/ANMS meeting. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:113–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creel WB, Abell TL, Lobrano A, Deitcher SR, Dugdale M, Smalley D, et al. To clot or not to clot: Are there predictors of clinically significant thrombus formation in patients with gastroparesis and prolonged IV access? Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1532–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, Bisschops R, Sifrim D, Verbeke K, et al. Clinical trial: A randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleski R, Anderson MA, Hasler WL. Factors associated with symptom response to pyloric injection of botulinum toxin in a large series of gastroparesis patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2634–42. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0660-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones MP, Maganti K. A systematic review of surgical therapy for gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2122–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medtronics. What is a humanitarian device? [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 2]. Avialable from: www.medtronics.com .

- 8.National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Interventional Procedure Guidance 103. 2004. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 4]. Avialable from: www.nice.org .

- 9.Abell TL. Gastric electric stimulation is a viable option in gastroparesis treatment. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:E8–13. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayinala S, Batista O, Goyal A, Al-Juburi A, Abidi N, Familoni B, et al. Temporary gastric electrical stimulation with orally or PEG-placed electrodes in patients with drug refractory gastroparesis. Gastroint Endosc. 2005;61:455–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abell TL, Johnson WD, Kedar A, Runnels JM, Thompson J, Weeks ES, et al. A double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of temporary endoscopic mucosal gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:496–503-e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson S, Ringstrom G, Elfvin A, Simren M, Lonroth H, Abrahamsson H. Temporary percutaneous gastric electrical stimulation: A novel technique tested in patients with non-established indications for gastric electrical stimulation. Digestion. 2011;83:3–12. doi: 10.1159/000291905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elfvin A, Gothberg G, Lonroth H, Saalman R, Abrahamsson H. Temporary percutaneous and permanent gastric electrical stimulation in children younger than 3 years with chronic vomiting. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abidi N, Starkebaum WL, Abell TL. An energy algorithm improves symptoms in some patients with gastroparesis and treated with gastric electrical stimulation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:334–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abell T, McCallum R, Hocking M, Koch K, Abrahamsson H, Leblanc I, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation for medically refractory gastroparesis. Gastroenterol. 2003;125:421–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00878-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCallum RW, Snape W, Brody F, Wo J, Parkman HP, Nowak T. Gastric electrical stimulation with Enterra therapy improves symptoms from diabetic gastroparesis in a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:947–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Grady G, Egbuji JU, Du P, Cheng LK, Pullan AJ, Windsor JA. High-frequency gastric electrical stimulation for the treatment of gastroparesis: A meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2009;33:1693–701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu H, Lin Z, Zhong L, McCallum RW, Hou X. Treatment of high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1017–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCallum RW, Lin Z, Forster J, Roeser K, Hou Q, Sarosiek I. Gastric electrical stimulation improves outcomes of patients with gastroparesis for up to 10 years. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, et al. Development and validation of a patient-assessed gastroparesis symptom severity measure: The Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:141–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: A joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:753–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]