Abstract

Background:

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disclosure offers important benefits to people living with HIV/AIDS. However, fear of discrimination, blame, and disruption of family relationships can make disclosure a difficult decision. Barriers to HIV disclosure are influenced by the particular culture within which the individuals live. Although many studies have assessed such barriers in the U.S., very few studies have explored the factors that facilitate or prevent HIV disclosure in India. Understanding these factors is critical to the refinement, development, and implementation of a counseling intervention to facilitate disclosure.

Materials and Methods:

To explore these factors, we conducted 30 in-depth interviews in the local language with HIV- positive individuals from the Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre in Gujarat, India, assessing the experiences, perceived barriers, and facilitators to disclosure. To triangulate the findings, we conducted two focus group discussions with HIV medical and non-medical service providers, respectively.

Results:

Perceived HIV-associated stigma, fear of discrimination, and fear of family breakdown acted as barriers to HIV disclosure. Most people living with HIV/AIDS came to know of their HIV status due to poor physical health, spousal HIV-positive status, or a positive HIV test during pregnancy. Some wives only learned of their husbands’ HIV positive status after their husbands died. The focus group participants confirmed similar findings. Disclosure had serious implications for individuals living with HIV, such as divorce, maltreatment, ostracism, and decisions regarding child bearing.

Interpretation and Conclusion:

The identified barriers and facilitators in the present study can be used to augment training of HIV service providers working in voluntary counseling and testing centers in India.

Keywords: Disclosure, fear, human immunodeficiency virus, people living with HIV/AIDS, social stigma

There are an estimated 2.31 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in India. The vast majority of HIV cases in India are attributed to unprotected sex.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued guidelines for secondary HIV prevention which include the promotion of correct and consistent condom use, as well as disclosure to sexual partners.[2,3] HIV disclosure is a critical component of HIV prevention, as partners are more likely to practice safer sex when they know their partner is HIV-positive.[4] Disclosure of HIV to sexual partners can lead to counseling, testing and treatment, and enables the partners to make informed reproductive health decisions.[5,6,7]

Although HIV disclosure offers certain benefits, especially for partners, there are several barriers for the HIV-positive individuals to disclosing, including being blamed for having HIV, fear of stigma and discrimination, as well as potential disruption of relationships.[2,8,9]

Some studies on disclosure have been conducted in South India, but no published study to date has focused on the experiences and beliefs of PLWHA and HIV service providers related to HIV disclosure in the western state of Gujarat.[8]

In the Indian culture, group membership, particularly family membership, often plays a large role in how individuals view themselves. Therefore, HIV disclosure may pose greater risks than it does in those cultures where families do not play a pivotal role, making non-disclosure seem more desirable than disclosure.[8,10] Moreover, in India, where norms may limit women's social freedoms, HIV-infected men can withhold disclosure from their female partners without fear of repercussions.[11] In addition, in such a cultural context, it may be challenging for HIV-infected women to voluntarily disclose their HIV status to their male partners and joint families in which they often live.

In this study, we sought to understand the disclosure experiences of PLWHA in Gujarat India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participant selection and recruitment

In-depth interviews with PLWHA

A sample of 30 HIV-infected individuals from a Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre (ICTC) in Vadodara, Gujarat, India were selected to participate in individual face-to-face in-depth interviews after pilot testing. Researchers continued recruitment until saturation of themes was achieved.

HIV-infected patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were: (1) English-or Gujarati-speaking; (2) 18 years or older; and (3) diagnosed with HIV for at least 3 months. All interviews were conducted in a private area by trained, bilingual staff after taking written informed consent. Each in-depth interview lasted approximately 2 h and followed a culturally sensitive semi-structured interview guide. Two note-takers were present at each interview to document the dialogue verbatim and take notes, including non-verbal communication. Participants received a reimbursement of 500 rupees for participation.

Focus groups with HIV service providers

Fifteen HIV service providers were recruited to participate in focus group discussions. Two focus groups were convened, one with seven medical doctors and the other with eight non-medical providers. HIV service providers were eligible to participate if they were: (1) Gujarati-speaking; (2) 18 years or over; and (3) had worked with HIV-positive patients for more than 1 year as either a medical doctor, a non-governmental organization staff member, integrated counselling and testing counselor, or peer educator for HIV-positive persons. A written informed consent was obtained. Each of the focus groups lasted about 2 hours and was audio-recorded with prior permission of the participants. The medical doctors were given 2500 rupees and non-medical providers were given 1500 rupees for their participation.

The entire research protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of both the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA and the Medical College, Baroda, India. The study was conducted during January 2009-March 2010.

Study tools and training

The in-depth interviews and focus group guides were developed by research teams in India and the U.S. In addition, a Community Advisory Board (CAB), comprising experts from the field of social work, medical providers, and HIV consultants was convened to discuss and refine the content of the qualitative instruments. The in-depth interview guide was designed to assess topics pertaining to HIV disclosure processes, perceived barriers and facilitators to disclosure, and HIV-associated stigma and discrimination related to disclosure among HIV-positive individuals.

The following topics were explored with the HIV service providers: (1) Secondary prevention services provided to PLWHA; (2) the advice they gave to PLWHA regarding whom to disclose to and why; and (3) the consequences that they perceived their clients faced after disclosure.

Data analysis

Extensive notes of in-depth interviews were recorded in Gujarati, and translated into English. The focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim in Gujarati from the audio-recordings and then the transcripts were translated into English.

In the early phase of coding, we based initial themes on topics covered in the interview/focus group discussion (FGD) guides. In the later phases, in-depth interview and FGD transcripts were read several times and content analyzed, respectively using the technique of open coding to discover conceptual patterns, or themes, in the text. Research staff in India and U.S. coded the 8 of the 30 interview transcripts independently and then met to discuss the codes and both the FGDs, and refined the code definitions. Once all of the interviews were coded, a reliability exercise was conducted for the in-depth interviews. Two independent researchers randomly selected and coded five transcripts. Based on the reliability exercise, over 90% of the codes matched with the codebook developed by the study staff. In all, two codebooks were generated for the interview and FGDs respectively. All interviews and FGDs were coded using MAXQDA software, 2007 (Berlin, Germany).

Once the interview and FGD codebooks were generated, a triangulation technique was used to analyze which themes from the HIV-positive individuals and from HIV service providers’ respective perspectives supported as well as which contradicted one another.

RESULTS

Demographic profile of HIV-infected patients

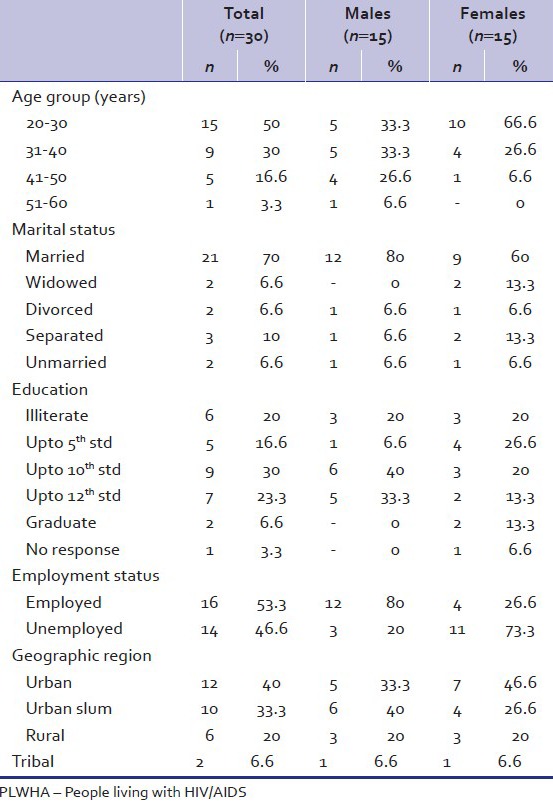

There were 30 HIV-infected patients, equal number of men and women, who participated in the study. Their demographic details have been represented in Table 1. Among the total patients, majority (both men and women) were from the younger age groups of 20-30 years and 31-40 years as compared to the older age groups of 41-50 years and 51-60 years. About three-fourth of the patients were married, a couple of female patients were widowed, a couple of patients (equal number of men and women) were divorced, few patients (more women than men) were separated from their spouse and a couple of patients (equal number of men and women) were unmarried at the time of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic details of PLWHA attending SSG hospital, Vadodara

The highest level of education among the patients was up to graduation which was found among a couple of female patients. In case of the male patients, less than half of them were educated up to 10th standard and about one-third were educated up to 12th standard. There were equal number of men and women among one-fifth of the patients who were illiterate. As regards employment, more than half of the patients (more men than women) were employed at the time of the study. Among the patients selected for the study from Vadodara district, less than half were from urban areas, one-third were from urban slums one-fifth were from rural areas and a couple of patients were from tribal areas.

Five broad categories related to disclosure emerged from the textual data.

Fear of stigmatization

Stigma associated with HIV was described as a barrier to disclosure because participants perceived HIV-positive status to have a negative impact on PLWHA and their children. The potential for HIV stigma to limit children's marriage prospects was particularly worrisome and cited as a reason not to disclose one's serostatus to people other than a spouse. A widowed female participant aged 30 years said, “It would have adverse effects on my son; the school might create problems for him. People may break relations and behave badly with me and my family as they consider HIV as a bad disease.” In addition, a 33-year-old widow and a mother of three children, anxious about their future said, “I fear that if I disclose my HIV positive status to everyone, it might affect my daughters’ marriage prospects.”

Participants perceived that many of their friends and family held misconceptions about HIV which would lead to increased stigma and mistreatment after disclosure. A married female aged 28 years said, “It would create a lot of problems for us, even if there is a slight indication in the society. We would not even be able to go out. People believe that one is infected by HIV only because of illicit relations.”

A separated female participant aged 42 years narrated, “I had not disclosed my positive status to relatives and neighbors, but my husband revealed my positive status in his family and neighborhood. Now, all my in-laws have cut off their relations with me and my son and neighbors discriminate against us. So finally we had to move out of that place. A person's life is ruined once he is infected with HIV.”

Findings from focus groups corroborated these data. A female medical service provider stated “PLWHA should not disclose their HIV status to the community due to HIV-related discrimination.”

Reasons for nondisclosure

The desire to protect others from the pain of knowing about their illness motivated some participants not to disclose. This concern seemed particularly salient in decisions about disclosing to parents, particularly if the parents were old or in poor health, or because they feared that the reality would be too painful and agonizing for their parents. A married male participant aged 32 years, explained, “I have not revealed my HIV positive status to my mother as I know that she would not be able to bear the reality.”

HIV service providers pointed out that in some cases, HIV-positive male participants withheld disclosure to their prospective spouse for fear of rejection, in turn passing infection on to her after marriage. A remarried male participant, aged 44 years, who had not disclosed his serostatus to his wife, discussed his dilemma saying, “I have never practiced sex without using condoms saying I don’t want children. But my wife (who is unaware of my serostatus) fights a lot with me as she wants children. I sometimes have to beat her.”

Involuntary vs. voluntary disclosure

There were instances where family members disclosed participants’ HIV-positive status to others without their consent or will or in an “involuntary” manner. A divorced male participant aged 35 years, upset and disappointed by his ex-wife's disclosure of his HIV status said, “She told her brother, who in turn told her parents and then my father came to know.”

In half of the participants, physical incapacity and health problems were cited as reasons why their HIV-positive status was disclosed involuntarily to family members. A married male participant aged 44 years who disclosed his HIV-positive status due to his ill health, stated “I have not told anyone. I have only told my mother as I was feeling weak and I could not even walk. So I had to tell my mother.”

Medical providers stated that it was important for HIV-positive patients to disclose to their families, to protect caregivers from the potential risk of HIV infection.

A married HIV-infected female participant aged 32 years, described how her and her husband's positive HIV status was disclosed involuntarily, “My husband's condition did not improve at all, so the doctor asked to get the HIV test done. His report came positive, but he kept it a secret for 15 days. The doctor then asked me to get my HIV test done. My report also came positive.”

While involuntary disclosure was a common thread among the participants, some discussed experiences of voluntary disclosure. Voluntary disclosure occurred when participants felt morally obligated to divulge their serostatus to a spouse so s/he could get tested for HIV. A divorced male participant aged 30 years, who voluntarily disclosed his HIV-positive status to his wife stated, “After reading the report, I thought this should not be kept a secret. So I told everything to my parents and wife. The next day I took my wife and 11-year-old daughter for the test. My wife was diagnosed positive and my daughter, negative. My wife and I are divorced for 1-1/2 years now.” Another reason participants gave for voluntarily disclosing their HIV-positive status was to obtain emotional and physical support from family. An example is this explanation from a married female participant aged 26 years, who gave her reason for the decision to disclose her and her husband's HIV-positive status to their parents, “We told this to our parents only as they care for us.”

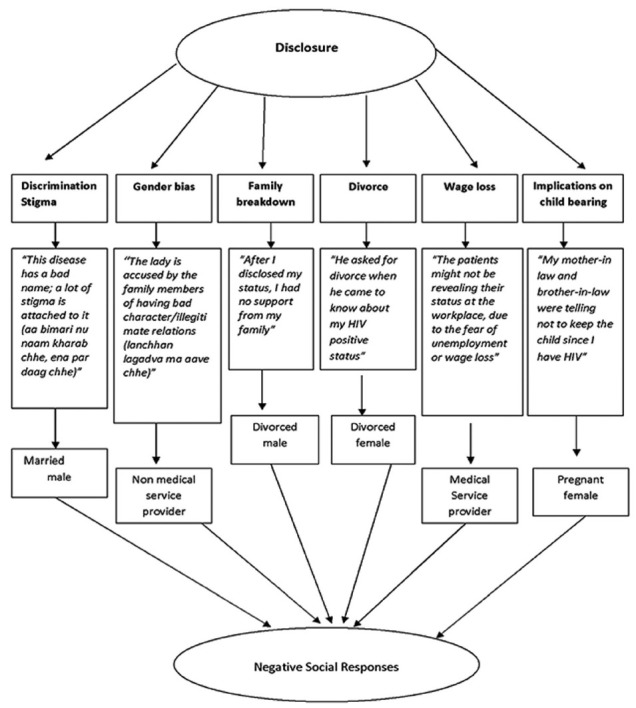

Consequences of disclosure

There are many consequences of disclosure [Figure 1], but a couple of salient themes are presented below. A severe consequence of disclosure was family disruption leading to separation and divorce. A female participant aged 28 years, said “My (second) husband was told everything about HIV. But he still did not accept it and harassed me. Then he asked for a divorce, which I did give to him.” Disclosure also impacted reproductive decision-making. A 21-year-old pregnant female participant, talked about her dilemma, “My mother-in law told me not to keep the child because I had HIV, the child could get it from me. So we went for abortion. But the doctors told us to take medicines and assured us with a 99% guarantee that the child would be HIV-negative and asked us to decide whether we want to keep the child or not. So we decided to start medicines and keep the child.” A divorced female participant aged 28 years expressed her grief, “The doctor told me to get my CD4 count tested. My CD4 count then was 79. So the doctor told me to abort the child as my CD4 count was low. So we aborted the child.”

Figure 1.

Consequences of disclosure

Some married female participants living in joint families, talked about being blamed by their mothers-in-law for either placing their son at risk for HIV or for being the source of their son's HIV infection. A married female participant, aged 35 years, said, “My mother-in-law held me responsible for her son's HIV infection. She doubted my chastity. For every bad thing the daughter-in-law is always blamed.” Other women became aware of their serostatus only after being remarried and getting tested for HIV when they became pregnant. A divorced female participant aged 28 years, said with a lot of emotion, “ My first husband died due to HIV. My in-laws never told me about his HIV positive status even after his death. During my second marriage, I came to know about my being HIV positive when I was pregnant again.” A counselor described this incident, “ I had this case of an unmarried HIV-positive male. I advised him that whenever you get married, you either marry a positive person like yourself or inform the person about your positive status beforehand. After a few months, that same person came for getting his wife's HIV test done. His wife was found positive; he had not informed his wife about his HIV-positive status before marriage.”

Benefits of disclosure

Although majority of patients described the barriers of disclosure, some HIV service providers and patients described the benefits. A female non-medical service provider explained, “We try to explain to the patients that if they disclose their status to their families, they would take better care of them. If you tell any member of your family, who is close to you, then it would be better for you.” Medical service providers believed that HIV-positive patients would benefit from treatment by telling their providers about their seropositive status when going for any kind of treatment. This would also allow doctors to screen for tuberculosis, one of the most common opportunistic infections among PLWHA in India.

Positive behavior from friends and neighbors after revelation of participants’ serostatus encouraged disclosure. A married female participant said, “ Those persons in the neighborhood to whom I have disclosed my status, are good. They say that this disease does not spread by talking to an infected person or touching, so there is no harm in even eating food prepared by me.”

DISCUSSION

HIV infection has often been associated with negative public reactions. Negative reactions influence the behavior of PLWHA and can undermine HIV disclosure. In India, HIV is perceived by some to be associated with an immoral lifestyle, which may contribute to HIV-related discrimination and stigmatization.[12] Such perceptions can negatively affect families, communities, workplaces, schools, and health-care settings.

Findings from this study revealed several factors which influenced the decision to disclose one's positive HIV status, including perceived HIV-associated stigma, fear of discrimination, and family breakdown. Fear of social stigma prevented HIV-positive participants from disclosing their status immediately to their partners and families which contributed to social isolation.

This study also revealed that most of the HIV-positive wives disclosed their status to their husbands, whereas only a few of the HIV-positive husbands revealed their status to their wives. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Kolkata, all of the female patients (100%) had disclosed their serostatus to their sexual partners, as compared to 65% of male patients.[7] Lack of disclosure and resulting secrecy on the husband's part contributed to conflict in the relationship. In one case, the husband insisted on condom use to protect his wife, but his wife resisted condom use because of her desire for children, which resulted in intimate partner violence (IPV). The wife's decision to have children may have been different had she known about her husband's HIV status, which may have prevented IPV altogether.

HIV service providers have an important role, as they may help foster HIV disclosure. In this study, many non-medical service providers explained the benefits of disclosure to their clients including spousal and family support. However, some findings of the present study also suggest discriminatory practices by HIV service providers which undermine the delivery of HIV prevention services including facilitating disclosure. In one qualitative study conducted in Southern India, HIV-positive women felt discriminated against by their own health-care providers.[13] One study reported that negative attitudes and discriminatory behaviors by providers towards PLWHA[14] indicated a need for ethics training. Additional and ongoing training in these areas are critical in creating environments supportive of HIV disclosure.

Our findings also showed that involuntary disclosure was more common than voluntary disclosure among HIV-infected participants. Voluntary disclosure occurred when participants felt morally obliged to divulge their serostatus to their spouse or due to obtain emotional support from their family. A similar pattern regarding disclosure emerged from discussions with health service providers except that they felt that patients also disclosed their HIV-positive status to close friends. In western countries, disclosure to friends is more common as they may be more supportive than family members.[15] However, in the present study, fear of discrimination by friends, peers, and colleagues at their workplace led to non-disclosure of HIV-positive status by participants.

This study indicated some benefits of disclosure to family including: Spousal support, care from other family members, protecting the seronegative spouse from HIV, and avoiding unintended pregnancy. However, although there are several benefits to disclosure, including the prompt HIV testing of sexual partners, it may not be enough given that HIV-related stigma can prevent HIV testing and treatment, which reinforces the notion that that the person who has the illness can be identified as the “marked other” via testing. Addressing HIV-related stigma as a way to increase HIV disclosure remains a critical area for intervention.

Given the cultural context in India, gender-specific approaches to enhance HIV disclosure need to be considered. There has been a suggestion in previous studies about individualized approaches to post-test counseling, including enhanced support services for HIV-positive women and public education to de-stigmatize HIV-disease, particularly because HIV-positive women are more often at the receiving end of discrimination and HIV-associated stigma when compared to men. In addition, HIV-positive women are looked upon with suspicion and their moral character is questioned, especially when they are tested earlier than their spouse.[16] Our study showed similar findings with respect to HIV-positive test results having a disproportionate negative impact on women. Couples-based counseling models which focus on both the seropositive and seronegative partner may also be critical in preventing HIV transmission.[17]

CONCLUSIONS

HIV prevention counseling in integrated counselling and treatment centre must address issues of fear of disclosure, potential negative consequences of disclosure, including stigma and discrimination when disclosing HIV-positive serostatus. Training local counselors and other HIV service providers in the identified barriers and facilitators of serostatus disclosure is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) and the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine at the Medical College Baroda. We would also like to thank Ross Oglesbee for her administrative assistance and support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: National Institute of Health (NIH) and Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for funding. NIH 2007 Parent grant no. 1 RO1 MH069989, Supplement NOT-AI-07-022 ICMR HIV/INDOUS/29/2007-ECD-II

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2007. National Institute of Health and Family Welfare. Report on annual HIV sentinel surveillance 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: Implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS/WHO; 2000. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Health Organization (WHO). Opening up the HIV/AIDS epidemic: Guidance on encouraging beneficial disclosure, ethical partner counseling, and appropriate use of HIV case reporting. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sri Krishnan AK, Hendriksen E, Vallabhaneni S, Johnson SL, Raminani S, Kumarasamy N, et al. Sexual behaviors of individuals with HIV living in South India: A qualitative study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19:334–45. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armistead L, Morse E, Forehand R, Morse P, Clark L. African-American women and self-disclosure of HIV infection: Rates, predictors, and relationship to depressive symptomatology. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalichman SC, DiMarco M, Austin J, Luke W, DiFonzo K. Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2003;26:315–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1024252926930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taraphdar P, Dasgupta A, Saha B. Disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:280–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra PS, Deepthivarma S, Manjula V. Disclosure of HIV infection in south India: Patterns, reasons and reactions. AIDS Care. 2003;15:207–15. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel K, Lekas HM, Schrimshaw EW. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners by HIV-infected women before and after the advent of HAART. Women Health. 2005;41:63–85. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna VA, Bhatti RS, Chandra PS, Juvva S. Unheard voices: Experiences of families living with HIV/AIDS in India. Contemp Fam Ther. 2005;27:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore EP. Women, Family, and Child Care In India: A World in Transition. American Ethnologist. 1999;26:1021–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharat S, Aggleton P, Tyrer P. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2001. India: HIV and AIDS-related discrimination, stigmatization and denial. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas B, Nyamathi A, Swaminathan S. Impact of HIV/AIDS on mothers in southern India: A qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:989–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahendra VS, Gilborn L, Bharat S, Mudoi R, Gupta I, George B, et al. Understanding and measuring AIDS-related stigma in health care settings: A developing country perspective. SAHARA J. 2007;4:616–25. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohanan P, Kamath A. Family support for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006046.pub2. CD006046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mawar N, Sahay S, Pandit A, Mahajan U. The third phase of HIV pandemic: Social consequences of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination and future needs. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:471–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumarasamy N, Safren SA, Raminani SR, Pickard R, James R, Krishnan AK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to antiretroviral medication adherence among patients with HIV in Chennai, India: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:526–37. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]