Abstract

We present the case of a 57-year-old male patient diagnosed with chronic lymphoid leukaemia (CLL) B-cell type along with moderate anaemia. On follow-up investigations the aetiology of anaemia turned out to be pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) on trephine bone biopsy with an elevated serum erythropoietin level. The patient received blood transfusion support. He showed remarkable improvement on oral corticosteroids (prednisolone 60 mg/daily dose) with no further requirement of blood transfusion over next 3 months. However, when the dose of steroid was tapered down to 10 mg/day, the anaemia reappeared. An increase in the dose of steroid brought the haemoglobin level back to normal. Anaemia in CLL can be due to many reasons, of which PRCA is an uncommon association occurring in only around 1% of patients with CLL and usually refractory to the conventional treatment with steroids. This PRCA secondary to CLL is considered to be immune in origin and a response to combination of immunosuppressive therapy such as steroids, cyclosporine, rituximab is anticipated. Our case responded completely to oral steroids alone.

Background

Pure red cell aplasia in (PRCA) adults is a rare cause of anaemia1 and described only about a century ago. It may be associated with thymoma and/or other immunological disorders.2 Anaemia in CLL can be due to many reasons. In advanced and end stage CLL it is due to replacement of normal marrow by the leukaemic cells and marrow failure.3 Other important cause for anaemia in CLL is autoimmune haemolysis. PRCA in CLL is rare, occurring in around 1% patients with CLL. Chikkappa et al4 estimated the prevalence at 6%, but it was later found to be an exaggeration and reported to be only 1%. PRCA in CLL is immunologically mediated through a complex cellular and humoral immune response on erythroid progenitor cells.5 PRCA is usually treated with immunosuppressants and biological agents like rituximab. However, acquired PRCA in CLL is usually refractory to conventional measures and has a tendency to relapse during the course of treatment requiring transfusion support. We report a case of CLL with PRCA which responded to oral corticosteroid alone with complete hematological recovery.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with exertional breathlessness, excessive fatigue and weight loss. Clinical examination revealed pallor without any organomegaly or lymphadenopathy. A clinical diagnosis of CLL with severe anaemia was made for which has to be evaluated.

Investigations

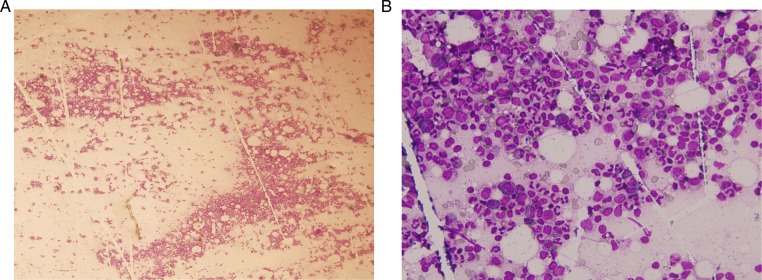

Complete blood counts were Hb 7.0 g%, total leucocyte count 25 100 cells/mm3, differential count polymorphs 5% lymphocytes 91% eosinophils 3 and ESR 92 mm in first hour. Peripheral blood smears revealed occasional smudge cells. Serology against HIV I and II, HBV surface antigen and hepatitis C virus were negative. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy showed hypercellular marrow with leucemic infiltration and supported the diagnosis of B-cell CLL (figure 1A). The patient was initially supported with blood transfusions. He was rehospitalised 6 months later with Hb 3.5 g%, total leukocyte count (TLC) 18 000 cells/mm3, platelet count 1.67 lakh/mm3, ESR 97 mm in first hour. Patient received four units of packed red blood cell. Further laboratory investigations revealed marked reticulocytopenia with a retic count of 0.29%. Direct and indirect Coomb's tests were negative on two occasions. Serum B12 levels were 868.1 pg/mL and ferritin levels were 92.7 ng/mL. Repeat bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed marked erythroid hypoplasia suggestive of PRCA (figure 1B). Serum erythropoietin levels were extremely high at 2000 mIU/mL. Serology for Parvo virus B19 tested negative. Possibility of thymoma was not corroborated with the radiological imaging studies. A diagnosis of acquired PRCA secondary to CLL was made.

Figure 1.

(A) Photomicrograph of bone marrow aspiration showing leukaemic infiltration of bone marrow suggestive of chronic lymphoid leukaemia. (B) Photomicrograph of repeat bone marrow aspiration showing marked paucity of erythroid precursors suggestive of red cell hypoplasia.

Differential diagnosis

CLL with severe anaemia attributed to severe haemolysis.

CLL with severe anaemia due to bone marrow failure secondary to tumour infiltration itself.

CLL with Pure red cell aplasia.

Treatment

A diagnosis of acquired-PRCA secondary to CLL was made and patient. He has already received cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy for CLL but his Hb level did no improve and he required a blood transfusion. He was then started on oral prednisolone at a daily dose of 60 mg (1 mg/kg body weight.) with other haematinics. Blood counts were repeated.

Outcome and follow-up

After 2 weeks his Hb count improved significantly to 10.0 g% and he was discharged on the blood count of Hb 10.9 g%. However, when the dose of steroid was tapered down to 10 mg/day, the anaemia reappeared. An increase in the dose of steroid to 60 mg daily brought the Hb level back to normal. The patient improved symptomatically and was discharged on above treatment with an advice to follow-up in outpatient department (OPD). The patient was in our regular follow-up. He maintained a normal Hb count during his OPD follow-up till 2 years when the complete blood count revealed Hb 11.5 g%, TLC 10 700 cells/mm3, platelet counts 3.4 lakh/mm3 after 1 year of discharge. His last Hb level which was performed 5 months back is 11 g% without any need for blood transfusion. A decision regarding adding immunosupressants was made initially but since the patient responded very well to oral steroids, he was not started on that therapy.

Discussion

PRCA was first recognised in 1922 and was described as a condition in which bone marrow erythroid precursors are nearly absent with normal megakaryocytes and white cell precursors.1 Chronic PRCA can be constitutional or congenital (which is Diamond-Blackfan syndrome in children or acquired PRCA in adults) and is known to be associated with other disorders such as thymoma, haematological malignancies, immunocompromised state as HIV infection.6 7 An acute form of PRCA is known to occur following viral infections especially the Parvo virus B19 infection. A chronic form of PRCA is also reported to be associated with persistent Parvo virus B19 infection especially in the elderly with immunocompromised state.8 The PRCA can also be induced by certain chemotherapeutic drugs and most of these cases recover rapidly when the affected drug is withdrawn.9 10 The present case belonged to the acquired chronic PRCA developing in a patient with CLL.

The anaemia in CLL can be attributed to many factors notably a conditioned folate deficiency, autoimmune haemolysis, hypersplenism and also the overcrowding of marrow with replacement of normal marrow by leukaemia cells leading to marrow failure. Rarely it is attributed to PRCA, the pathogenesis of which is not well understood. T-lymphocyte dysfunction inhibiting the growth of erythroid progenitor burst-forming and colony-forming units is postulated as a mechanism.11 The number of those T cells is reported to decrease markedly with effective therapy for PRCA.5 11 In India also PRCA in CLL is found to be attributable to autoimmune haemolysis mainly and malignant cell infiltration of the bone marrow.

Whereas acute PRCA is usually self-limiting and steroid responsive, the acquired PRCA is said to be refractory to conventional therapy with steroids and has also relapsed after treatment.12 This is more true of PRCA occurring in CLL. Our case responded well to oral corticosteroid alone.

Other immunosuppressive drugs like 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine and cyclosporine have all been used in cases refractory to steroids. Biological agents such as rituximab, alemtuzumab and anti-thymocyte globulin have been used for refractory cases.13–15 Autologous and non-myeloablative allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplantation and plasmapheresis have also been tried successfully in patients who are refractory to other therapy.15

Learning points.

Pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) secondary to CLL is a rare entity.

Secondary acquired-PRCA rarely responds to oral corticosteroid.

Patients with PRCA secondary to CLL should be given a trial of oral corticosteroids.

Footnotes

Contributors: PD was involved in writing the case summary and was the resident physician who treated the patient. NG was involved in managing the patient and drafting the case report. DD was involved in the management of the patient.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fisch P, Handgreitinger R, Schaefer H. Pure red cell aplasia. Br J Haematol 2000;2013:1010–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammus SS, Yunis AA. Acquired pure red cell aplasia. Am J Hematol 1987;2013:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zent CS, Neil E. Autoimmune complications in chronic lymphoid leukemia(CLL). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2010;2013:47–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chikkappa G, Zarrabi MH. Pure red-cell aplasia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1986;2013:339–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagasawa T, Abe T. Pure red cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia associated with T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1981;2013:1025–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willig T-N, Gazda H, Sieff CA. Diamond–Blackfan anemia. Curr Opin Hematol 2000;2013:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masaoka A, Hashimoto T, Shibata K, et al. Thymomas associated with pure red cell aplasia. Histologic and follow-up studies. Cancer 1989;2013:1872–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrzljak A, Kardum-Skelin I, Cvrlje VC, et al. Parvovirus B 19 (PVB19) induced pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) in immunocompromised patient after liver transplantation. Coll Anthropol 2010;2013:271–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson D-F, Gales M-A. Drug induced pure red cell aplasia. Pharmacotherapy 1996;2013:1002–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krantz SB. Diagnosis and treatment of pure red cell aplasia. Med Clin North Am 1976;2013:945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenzato G, Pezzutto L, Alberti OM, et al. T lymphocyte subpopulations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a quantitative and functional study. Cancer 1981;2013:2192–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghazal H. Successful treatment of pure red cell aplasia with rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2002;2013:1092–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiuqing RU, Howard AL. Successful treatment of refractory pure red cell aplasia associated with lymphoproliferative disorders with the anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab. Br J of Haematol 2003;2013:278–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robak T. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of autoimmune cytopenias. Eur J Haematol 2004;2013:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mouthon L, Guillevin L, Tellier Z. Intravenous immunoglobulins in autoimmune- or Parvovirus -B19 mediated pure red-cell aplasia. Autoimmun Rev 2005;2013:264–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]