Abstract

Aim and Objective:

The objective is to assess the prevalence of caries in children with perinatal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Materials and Methods:

Oral examination was performed on children aged 2-12 years with perinatal HIV infection who stayed at ‘Calvary Chapel home of hope for special children’ to assess decayed, missing, or filled primary teeth/decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (dmft/DMFT).

Results:

Prevalence of tooth decay in primary teeth (dmft) for the age group 2-6 years was 57.15% and 7-12 years was 20.0%. Prevalence of tooth decay in permanent teeth (DMFT), for the age group 7-8 years was 16.60% and 10-12 years was 21.42%. Of the 27 children examined, 59.25% were caries free, in which 40.0% were male children and 70.58% were female children.

Conclusion:

Based on these results we can conclude that oral hygiene can be maintained with a favorable dental behavior.

Keywords: Prevalence, perinatal HIV, pediatric

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated worldwide that there are 2.3 million human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive children from 0 to 14 years infected by mothers.[1] In children, the quality of life related to health should be considered differently from adults.[2] The high prevalence of HIV infection reinforces the need for dentists and their staff to update the prevention and treatment of diseases and the promotion and maintenance of oral health of individuals with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).[2]

Prior to 1992, information about dental caries in HIV-infected children was very limited.[3] Of the published articles on the oral manifestations of AIDS, virtually all addressed this issue only in an adult population. In one of these studies, HIV infected adults had a lower prevalence of dental caries when compared to a group of healthy adults from the same region of Zaire.[4] Another adult study found that there was an association between dental caries and Capnocytophaga keratitis.[5] A Russian study found a high incidence of dental caries in symptom free HIV-infected adults.[6] It was not until the late 1980s that investigators started to turn attention to the oral manifestations of HIV-infected children, but none of those earlier writings reported on the disease of dental caries.[7,8,9] Between 1992 and 1996 there were three published cross-sectional studies of dental caries in the primary teeth of HIV-infected children.[10,11,12] These studies showed that there was a higher prevalence of dental caries (including early childhood caries (ECC)) in the primary dentition of HIV-infected children as compared to healthy children. However, in a 1996 case-control study of caries prevalence in a group of children aged 1.5-12 years, Teles et al., reported a lower decayed, missing, or filled primary teeth (dmft) for HIV-infected children as compared to healthy children, as well as a higher decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (DMFT).[13] Vieira et al., reported that HIV-infected children (aged 2-12 years), who were less immunologically competent (CD4:CD8 <0.5 ratio) showed a greater DMFT/dmf index than HIV-infected children who were immunocompetent.[14]

Standard antibody testing is now available to determine a person's HIV status at an early age. However, because of the expense of the complex technology, health workers in developing countries–where 95% of the world's pediatric AIDS cases are found–must rely on early clinical manifestations of HIV infection.[9] Moreover, the use of disease markers prevalent in adult HIV infection is not necessarily effective in the pediatric AIDS population. CD4 lymphocytes, for example, where HIV primarily resides and multiplies, decline with the progression of HIV disease in infected adults; in children, however, a CD4 count alone is not a reliable marker of progressive disease because they tend to have higher and less consistent CD4 levels than adults.[10,15]

In the light of the above factors, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of dental caries in children with perinatal HIV infection.

HYPOTHESIS

Null hypothesis (H0)

The prevalence of dental caries in children with perinatal HIV infection is not different from that of normal children residing in the same region.

Alternative hypothesis (H1)

The prevalence of dental caries in children with perinatal HIV infection is higher than that of normal children residing in the same region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of data

Children aged 2-12 years staying at Calvary Chapel Home of Hope for Special Children, with perinatal HIV infection were chosen as subjects.

Method of collection of data

Twenty-seven subjects with perinatal HIV infection fulfilled the criteria and were included in the study. The participation of the subjects in the study was voluntary and a written informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the study.

Inclusion criteria

Children with perinatal HIV infection

Children stayed at Calvary Chapel Home of Hope for Special Children

Age group: 2-12 years

Exclusion criteria

Children with any oral lesions

Children on medications other than antiviral therapy

Chronic inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis which require medication.

Training and calibration

The investigator was trained in the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Government Dental College and Research Institute, Bangalore on 10 subjects. Calibration was done on 10 subjects who were examined twice using diagnostic criteria on the same day with a time interval of 1 hr between the two examinations, and then the results were compared to diagnostic variability. Agreement for assessment was 90%.

Examination

The examination procedure was carried out at the Calvary Chapel Home of Hope for Special Children under natural light by single investigator. The children were made to sit on a cement bench. The oral examination was performed according to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for oral health surveys. The diagnosis of developmental enamel defects was done according to the modified developmental defects of enamel index.

Examination was carried out using 27 mouth mirrors and 27 periodontal probes. Examination of children was undertaken to determine caries prevalence using dmft/DMFT, and developmental enamel defects. The examiner started with the upper left central incisor and continued distally through the second molar in the same quadrant. The same sequence was followed for the upper right, lower left, and lower right quadrants. Tooth surfaces were examined in the following order: Lingual, labial, mesial, and distal for anterior teeth and occlusal, lingual, buccal, mesial, and distal for posterior teeth [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Examination of child in the day light

Guardians were interviewed to obtain information on their children's dental health behaviors such as toothbrushing, diet, and fluoride; oral medication; and dental attendance were explored.

Data collected was used to estimate the mean number of teeth, the number of teeth with carious lesions, number of missing/extracted teeth, and number of teeth with restorations. Caries was defined by presence of decayed or filled teeth and was categorized as present or absent.

As the subjects stayed in the special home for children with HIV infection, a suitable control group was not found. Hence, the prevalence of dental caries (dmft and DMFT) in children with perinatal HIV infection was compared with the prevalence of dental caries in normal children residing in the same city, which was found in a large study conducted in Bangalore city.[16]

RESULTS

The study population was composed of 27 children, there were 62% (n = 17) female children and 38% (n = 10) male children. Twenty-seven children ranged in age from 2 to 12 years, with a mean age of 8.407 years. Neither developmental enamel defects nor the discrepancies in the average number of teeth for their age were found. All the 27 children brushed their teeth twice daily with a toothbrush and toothpaste to clean their teeth.

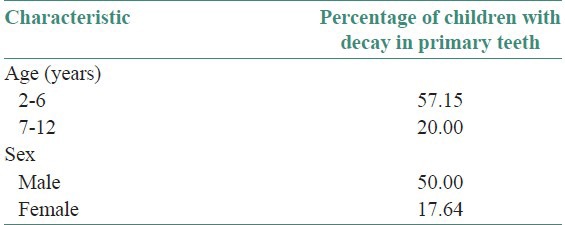

Prevalence of tooth decay in primary teeth (dmft) for the age group 2-6 years was 57.15%, for age group 7-12 years was 20.0%; 50.0% of male children were free of decay in the primary teeth, however 17.64% of female children were free of decay in the primary teeth [Table 1].

Table 1.

Percent of children with decay in primary teeth

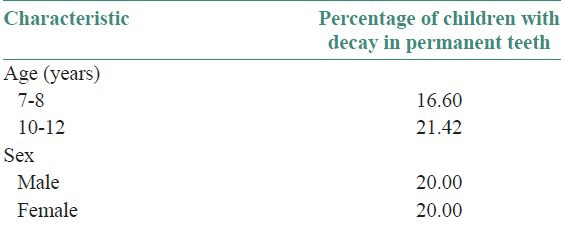

Prevalence of tooth decay in permanent teeth (DMFT) for the age group 7-8 years was 16.60% and 10-12 years was 21.42%. Twenty percent of male children had caries in their permanent teeth and 20.0% of female children had caries in their permanent teeth [Table 2].

Table 2.

Percent of children with decay in permanent teeth

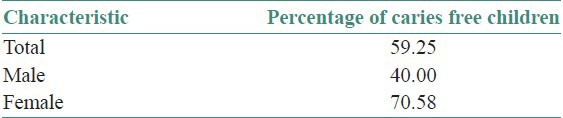

Of the 27 children examined; 59.25% were caries free, in which 40.0% were male children and 70.58% were female children [Table 3].

Table 3.

Percent of children free of caries

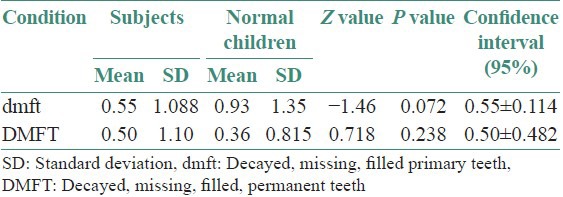

The dmft found in these children was 0.55 with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.088 and the DMFT was 0.50 with a SD of 1.10. The dmft found in children with perinatal HIV infection was low and was marginally significant (P = 0.072, i.e., P > 0.05; however P < 0.10) compared with that of normal children. However, no significant differences were found in DMFT of these children when compared with that of normal children (P = 0.238) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Caries prevalence among subjects and normal children

DISCUSSION

Oral health care is an important component of all round care for people with HIV infection.[17] The lack of healthy, functioning dentition can adversely affect the quality of life, complicate the management of medical conditions, and create or exacerbate nutritional and psychosocial problems.[18] Some antiretroviral drugs are sucrose-based in the form of a syrup or suspension such as Zidovudine and others may lead to decreased salivation, which makes them potentially cariogenic.[19]

In South Africa an oral examination was performed on 87 HIV positive children ranged between 3.2 and 7 years, who were not receiving antiretroviral treatment. Rampant caries early in childhood was found in 19 (21.8%) children, with five children suffering severe pain from multiple carious teeth.[20] The study in Romanian population consisted of 173 children in an age range of 6-12 years and noted severe dental caries in the majority of children (dmf surface index (dmfs)/dmft 16.9/3.7 and DMF surface index (DMFS)/DMFT 8.1/3.1).[21]

According to Howell, et al.,[10] the prevalence of caries in HIV children was very high, especially with deciduous dentition. Tofsky, et al.,[22] found that the mean cumulative dmfs score for HIV-infected cases was higher than for the control subjects for both the 2-5 year olds and the 6-11 year olds, (11.0 vs. 7.0) and (10.0 vs. 4.0, P=.02), respectively. A comparative study of the prevalence of caries, by Souza, et al.,[23] in HIV infected children and children without evidence of immunosuppression, showed statistically significant difference between the average mean dmft (5.29; 2.59) and DMFT (2.36; 0.74) of the two groups, respectively. Other recent studies showed that the high prevalence of caries in infected children seems to be greater in those that are in advanced stage of disease and with more severe degree of immunosuppression.[24]

Poorandokht, et al., found that 54 children of the 100 children examined had rampant caries and rampant caries was the most common oral manifestations of AIDS in those children (54%) followed by periodontal disease (44%), further authors suggested that rampant caries and severe periodontal diseases (mean CD4 count, 523 ± 297) might have caused tooth loss and denture use in some patients with severe immunosuppression, resulting in not being categorized as rampant caries.[25]

Beena, et al., found that the primary dentition group had a mean decayed, extracted, or filled teeth (deft) of 5.07 ± 5.29 and a caries prevalence of 58.62%; in the mixed dentition group the mean deft was 3.81 ± 3.41 and the mean DMFT was 1.40 ± 2.03 with caries prevalence of 86.20%. In the permanent dentition group the mean DMFT was 3.00 ± 2.37 with a caries prevalence of 76.47%.[26]

It was however observed that the prevalence of dental caries recorded in the present study was lower than those previously reported. Dental caries prevalence in these HIV positive children although lower than that seen in other studies, however did not differ significantly when compared to reports of healthy children residing in the same city.

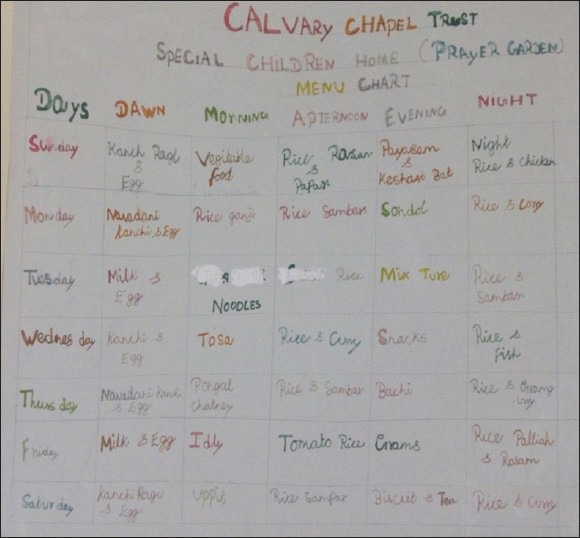

Although the exact reason for the low levels of dental caries prevalence recorded in this study was not apparent, it may be attributable to the general high level of oral health awareness and the diet they consumed which completely eliminated the added sugars, which leads to good oral health and restorative care [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Children diet chart

CONCLUSIONS

Children with perinatal HIV infection who stayed at Calvary Chapel Home of Hope had a favorable dental behavior and the caries experience was low.

Importance of this paper

Survival rates for children born with HIV who receive antiretroviral therapy are more than double those for children who do not. However, some antiretroviral drugs are sucrose based in the form of a syrup or suspension, such as Zidovudine, and others may lead to decreased salivation, which makes them potentially cariogenic.

Many recent studies have demonstrated high caries prevalence rates in these children, however in the present study we found a group of children taking ART with low prevalence of caries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Health Organization (WHO); 2006. [Last cited on 2009 Aug 31]. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). AIDS epidemic update. Special report on HIV/AIDS. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/EpiReport/2006/2006_EpiUpdate_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sílvia Helena de Carvalho Sales-Peres, Marta Artemisa Abel Mapengo, Patrícia Garcia de Moura-Grec, Juliane Avansine Marsicano, André de Carvalho Sales-Peres, Arsenio Sales- Peres. Oral manifestations in HIV+children in Mozambique. Ciência and Saúde Coletiva. 2012;17:55–60. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232012000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer I, Kobayashi R, Cannon M, Simon J, Cooley R, Rich K. Dental treatment of children with severe combined immunodeficiency. Pediatr Dent. 1983;5:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray P, Grassi M, Winkler J. The microbiology of HIV associated periodontal lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;16:636–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ticho B, Urban R, Safran M, Saggau D. Capnocytophaga keratitis associated with poor dentition and human immunodificiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalm. 1990;109:352–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kharchenko OI, Pokrovskii VV. The state of the oral cavity in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Stomatologiia (Mosk) 1989;68:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leggott P, Robertson P, Greenspan D, Wara D, Greenspan J. Oral manifestations of primary and acquired immunodeficiency disease in children. Pediatr Dent. 1987;9:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker B, Schaeffer D, Berson R. A combination of HIV antibody and HIV viral findings in blood and saliva of HIV antibody-positive juvenile hemophiliacs. Pediatr Dent. 1988;10:283–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falloon J, Eddy J, Wiener L, Pizzo Human immunodeficiency virus infection in children. J Pediatr. 1989;114:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell R, Jandinski J, Palumbo P, Shey Z, Houpt M. Dental caries in HIV-infected children. Pediatr Dent. 1992;14:370–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valdez I, Pizzo P, Atkinson J. Oral health of pediatric AIDS patients: A hospital-based study. ASDC J Dent Child. 1994;61:114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madigan A, Murray P, Houpt M, Catalanotto F, Feuerman M. Caries experience and cariogenic markers in HIV-positive children and their siblings. Pediatr Dent. 1996;18:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teles G, Perez M, Souza I, Vianna R. Clinical aspects of human immunodeficiency virus HIV) infected children. J Dent Res. 1996;75:316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viera AR, Ribeiro IP, Modesto A, Castro GF, Vianna R. Gingival status of HIV+children and the correlation with caries incidence and immunologic profile. Pediatr Dent. 1998;20:3169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdez I, Pizzo P, Atkinson J. Oral health of pediatric AIDS patients: A hospital-based study. ASDC J Dent Child. 1994;61:114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pramila M, Hiremath SS. Oral health status of handicapped children attending special schools in Bangalore city.Int. Journal of Contemporary Dentistry. 2011;2:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damle SG, Jetpurwala AK, Saini S, Gupta P. Evaluation of oral health status as an indicator of disease progression in HIV positive children. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr, João Pessoa. 2010;10:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baccaglini L, Atkinson JC, Patton LL, Glick M, Ficarra G, Peterson DE. Management of Oral lesions in HIV-positive pati ents. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:S50,e1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rwenyonyi CM, Kutesa A, Muwazi L, Okullo I, Kasangaki A, Kekitinwa A. Oral Manifestations in HIV/AIDS Infected Children. Eur J Dent. 2011;5:291–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blignaut E. Oral health needs of HIV/AIDS orphans in Gauteng, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19:532–8. doi: 10.1080/09540120701235636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaitz C, Wullbrandt B, Sexton J, Bourdon T, Hicks J. Prevalence of orodental findings in HIV infected Romanian children. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tofsky N, Nelson EM, Lopez RN, Catalanotto FA, Fine DH, Katz RV. Dental caries in HIV-infected children versus household peers: two-year findings. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souza IP, Teles GS, Castro GF, Guimarães L, Viana RB, Peres M. Prevalence of dental caries in HIV-infected children. Rev Bras Odontol. 1996;53:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro GF, Souza IP, Chianca TK, Hugo R. Evaluation of caries prevention program in HIV+children. Braz Oral Res. 1997;15:91–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davoodi P, Hamian M, Nourbaksh R, Ahmadi Motamayel F. Oral manifestations related to CD4 lymphocyte count in HIV-positive patients. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2010;4:115–9. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beena JP. Prevalence of dental caries and its correlation with the immunologic profile in HIV-Infected children on antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]