Abstract

In Arabidopsis, the ethylene-receptor signal output occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum and is mediated by the Raf-like protein CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE1 (CTR1) but is prevented by overexpression of the CTR1 N terminus. A phylogenic analysis suggested that rice OsCTR2 is closely related to CTR1, and ectopic expression of CTR1p:OsCTR2 complemented Arabidopsis ctr1-1. Arabidopsis ethylene receptors ETHYLENE RESPONSE1 and ETHYLENE RESPONSE SENSOR1 physically interacted with OsCTR2 on yeast two-hybrid assay, and green fluorescence protein-tagged OsCTR2 was localized at the endoplasmic reticulum. The osctr2 loss-of-function mutation and expression of the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgene that encodes the OsCTR2 N terminus (residues 1–513) revealed several and many aspects, respectively, of ethylene-induced growth alteration in rice. Because the osctr2 allele did not produce all aspects of ethylene-induced growth alteration, the ethylene-receptor signal output might be mediated in part by OsCTR2 and by other components in rice. Yield-related agronomic traits, including flowering time and effective tiller number, were altered in osctr2 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines. Applying prolonged ethylene treatment to evaluate ethylene effects on rice without compromising rice growth is technically challenging. Our understanding of roles of ethylene in various aspects of growth and development in japonica rice varieties could be advanced with the use of the osctr2 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines.

Introduction

Ethylene, a gaseous plant hormone, regulates many aspects of plant growth and development, such as responses to stress and pathogens, fruit ripening, senescence, (Anderson et al., 2004), and cell elongation (Alonso and Granell, 1995; Hua and Meyerowitz, 1998; Alexander and Grierson, 2002). Many studies have used mainly dicotyledonous plants to investigate the effects of ethylene. In contrast, knowledge of the roles of ethylene in lower plants and monocotyledonous plants is relatively scarce.

Previous studies of the ethylene effects on rice have focused mostly on flooding responses in a few specific varieties of the inidca rice cultivar. In varieties of indica floating rice (also called deep-water rice), flooding induces a burst of ethylene biosynthesis, which promotes gibberellin biosynthesis and abscisic acid degradation (van der Knaap et al., 2000; Saika et al., 2007; Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2008a ). As a result, internodal elongation is facilitated and the rice plant is able to grow above the water and survive. Two quantitative trait loci responsible for ethylene-induced internodal elongation in the deep-water rice varieties have been identified; they are members of the ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (ERF) family, namely SNORKEL1 (SK1) and SK2. Gibberellin treatment can replace ethylene treatment to induce internodal elongation in deep-water rice varieties, so rapid rice growth with flooding can be independent of ethylene (Hattori et al., 2009).

Unlike deep-water rice, the indica variety FR13A does not produce an elongated shoot and can survive with complete submergence in water. FR13A carries the SUBMERGENCE1A (SUB1A) gene that encodes an ERF protein conferring submergence tolerance (Xu et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2010). SUB1A expression is inducible by ethylene on submergence, and the DELLA proteins SLENDER RICE1 (SLR1) and SLENDER RICE LIKE1 (SLRL1) accumulate to inhibit shoot elongation (Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2008b ). The growth inhibition reduces energy consumption to facilitate growth recovery after submergence (Fukao et al., 2006). The SUB1A locus is absent in japonica varieties and is not functional in many indica varieties that are intolerant of submergence (Xu et al., 2006). Although the roles of ethylene in flooding responses are clearly revealed in deep-water rice and submergence-tolerant indica varieties, regular rice varieties do not show the rapid shoot elongation or growth inhibition on flooding. The general roles of ethylene in many aspects of rice growth and development remain to be fully addressed.

Arabidopsis ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2 (EIN2) and EIN3 are components in the ethylene signal transduction pathway promoting ethylene responses. Transformation studies show opposite effects of rice OsEIN2 antisense expression and EIN3-LIKE1 (OsEIL1) overexpression on seedling height and primary root growth (Jun et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2006). Overexpressing the rice ethylene receptor-like gene ETHYLENE RESPONSE2 (OsETR2) moderately alleviated seedling elongation and root growth alterations induced by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) (Wuriyanghan et al., 2009). Arabidopsis REVERSION- TO-ETHYLENE SENSITIVITY1 (RTE1) is a Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein that promotes the signal output from the ETHYLENE RESPONSE1 (ETR1) ethylene receptor. Treatment with the ethylene blocker 1- methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and overexpression of rice REVERSION-TO-ETHYLENE SENSITIVITY1 HOMOLOG1 (OsRTH1) each effectively prevented many aspects of ethylene-induced alterations in growth and gene expression (Zhang et al., 2012). These studies suggest that the ethylene signalling machinery is conserved in Arabidopsis and rice.

CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE-RESPONSE1 (CTR1) is a key component in Arabidopsis mediating the ethylene-receptor signal output, and ctr1 loss-of-function mutations result in a constitutive ethylene response (Huang et al., 2003). Isolation of rice mutants exhibiting a constitutive ethylene response will advance our knowledge of the effects of ethylene on rice throughout development. Here, we showed by a cross-species complementation test, mutant phenotype analyses, and dominant-negative effects with the expression of 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 that encodes the OsCTR2 N terminus that rice OsCTR2 is closely related to CTR1 and negatively regulates ethylene signalling. The osctr2 allele did not promote all aspects of ethylene-induced growth alterations, so OsCTR2 was not the only component mediating the ethylene-receptor signal output. Ethylene effects on aspects of rice growth and development could be evaluated with the use of the osctr2 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The wild-type japonica rice cultivars used were ZH11 and Dongjing (DJ), and the osctr2 allele was in the DJ background. The osctr2 mutant was from Dr Gyheung An (Kyung Hee University, Korea) (Jeon et al., 2000; Jeong et al., 2006) and was confirmed by PCR genotyping. Conditions for rice seed germination and growth were as described previously (Zhang et al., 2012). Arabidopsis seeds were stratified for 72h before germination; seedling phenotypes were scored after 80h of germination at 22 °C in the dark or 7 d of germination with illumination (16h light/8h dark). For gas treatment, Arabidopsis or rice seedlings were grown in an air-tight container with ethylene (100 µl l–1) or 1-MCP (5 µl l–1). 1-MCP was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Rohm & Haas China, Beijing), and the concentration was determined by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (Zhang et al., 2012). Arabidopsis seedlings were treated for 80h (etiolated seedlings) or 7 d (light-grown seedlings), and etiolated rice seedlings for 7 d after germination or 4 d for light-grown seedlings (Xie et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2012). For the senescence test, rice leaf segments were treated for 4 d (Zhang and Wen, 2010). Rice plants were cultivated in an experimental station in Shanghai. Ethylene concentration was determined by gas chromatography/flame ionization as described previously (Zhang et al., 2012).

Phylogenetic analysis

Plant CTR1-related proteins were searched for using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with Arabidopsis CTR1 as the query sequence. Redundant and short sequences were excluded. The sequences were aligned using ClustalX version 2.1 (Larkin et al., 2007), and a neighbour-joining tree was generated using MEGA5.0, with a bootstrap setting of 1000 (Tamura et al., 2011).

Transgenes and clones

To clone the Arabidopsis CTR1 promoter, the primer set AtCTR1OF and AtCTR1PR was used for PCR cloning. All primer sequences used for cloning are available in Supplementary data S1 at JXB online. Rice OsCTR2 and OsCTR3 cDNA clones were from the Rice Genome Research Center, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan. The primer set OsCTR2-F and OsCTR2-R was used to generate the OsCTR2 cDNA fragment for cloning CTR1p:OsCTR2. CTR1p:OsCTR2 was transformed into Arabidopsis ctr1-1 for a cross-species complementation test. The primer set OsCTR2-N-F and OsCTR2-NR was used to PCR clone the OsCTR2 1–513 fragment, with rice genomic DNA used as a template. The ER marker ER-rk has been described previously (Nelson et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2012). 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic rice lines were obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation into rice callus (ZH11 variety), and the resulting transgenic lines were obtained from independent calli. Phenotyping for 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines was performed in T3 or higher generations.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression involved the use of a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (ABI) with a SYBR Premix Ex Taq real-time RT-PCR kit (Takara). The primer set for ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 (ERF1) expression has been described previously (Liu and Wen, 2012b ). The primer sets for qRT-PCR are available in Supplementary data S1. Expression of actin (rice) and ubiquitin (Arabidopsis) were used for internal calibration. To measure the transcript copy number for CTR1 and OsCTR2 in Arabidopsis expressing CTR1p:OsCTR2, cDNAs for CTR1 and OsCTR2 were used as templates, serially diluted, and a standard curve for the cDNA copy number was drawn (R 2 ≥ 0.99). Total RNA was reversed transcribed with the use of oligo(dT), and CTR1 and OsCTR2 copy numbers were estimated against the standard curve by qRT-PCR.

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy for subcellular localization of fluorescently labelled proteins involved use of an Olympus FluoView FV1000 and FV10-ASW1.7 Viewer for data acquisition at the Core Facility Center of the Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences. Transgenes that expressed the fusion proteins were delivered by particle bombardment to onion epidermal cells or by Agrobacterium infiltration to tobacco leaf epidermis.

Statistical analyses

For Arabidopsis seedling hypocotyl measurement, at least 30 individual seedlings were measured and the hypocotyl length was described as mean ±SD. Gene expression analysis with qRT-PCR involved three independent biological samples, with each measurement repeated three times, and data are described as means ±SEM. At least 28 rice seedlings were scored for measurement of seedling height, primary root length, number of adventitious roots, and coleoptile length, and data are described as means ±SD. Chlorophyll a content was determined from six independent measurements, with leaf segments from at least three independent rice seedlings pooled for each measurement. The sample size for agronomic traits of rice plants is shown in Fig. 6. Student’s t-test was used for comparing paired means and Scheffe’s test for multiple means (α = 0.01).

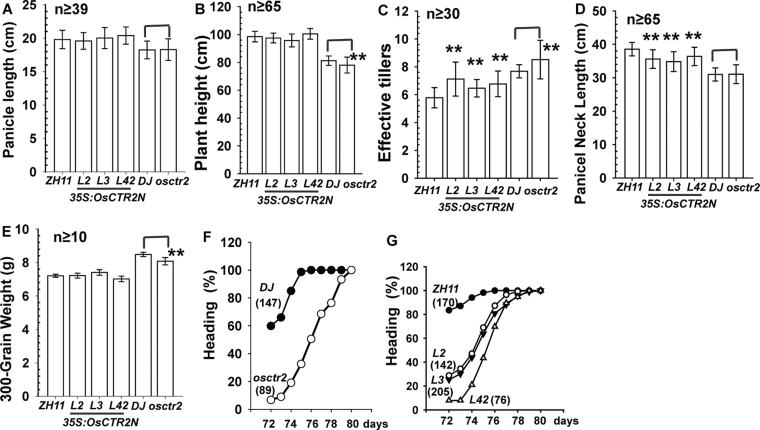

Fig. 6.

Quantification of yield-related agronomic traits. (A) Panicle length, (B) plant height, (C) effective tiller number, (D) panicle neck length, (E) 300-grain weight (gram), and (F) and (G) heading status of wild-type varieties (DJ and ZH11), osctr2, and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines. Data are means ±SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P<0.01. Sample sizes are as indicated or are shown in parentheses.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

A yeast two-hybrid assay and β-galactosidase activity measurement were performed as described previously (Clark et al., 1998; Xie et al., 2006). cDNA fragments encoding ETR1331–729 and ETHYLENE RESPONSE SENSOR1 (ERS1)130–613 were each cloned in pBTM116 and co-expressed with OsCTR21–513 (cloned in pGADT7) or CTR153–568 (in pGAD424) (Clark et al., 1998) in the yeast strain L40. β-Galactosidase activity was determined by OD578 (the OD was read every second for 600 s) from 8–10 independent yeast transformation lines, with chlorophenol red–β-d-galactopyranoside as the substrate, and the data are shown as means ±SD. For 5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) staining, yeast cells were grown on non-selective medium supplemented with X-gal (80mg l–1) for 24h at 30 °C.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of CTR1-related proteins

To identify proteins related to Arabidopsis CTR1 in rice, we performed a BLAST search and identified 64 CTR1-related proteins from 25 plant species for phylogenetic analysis.

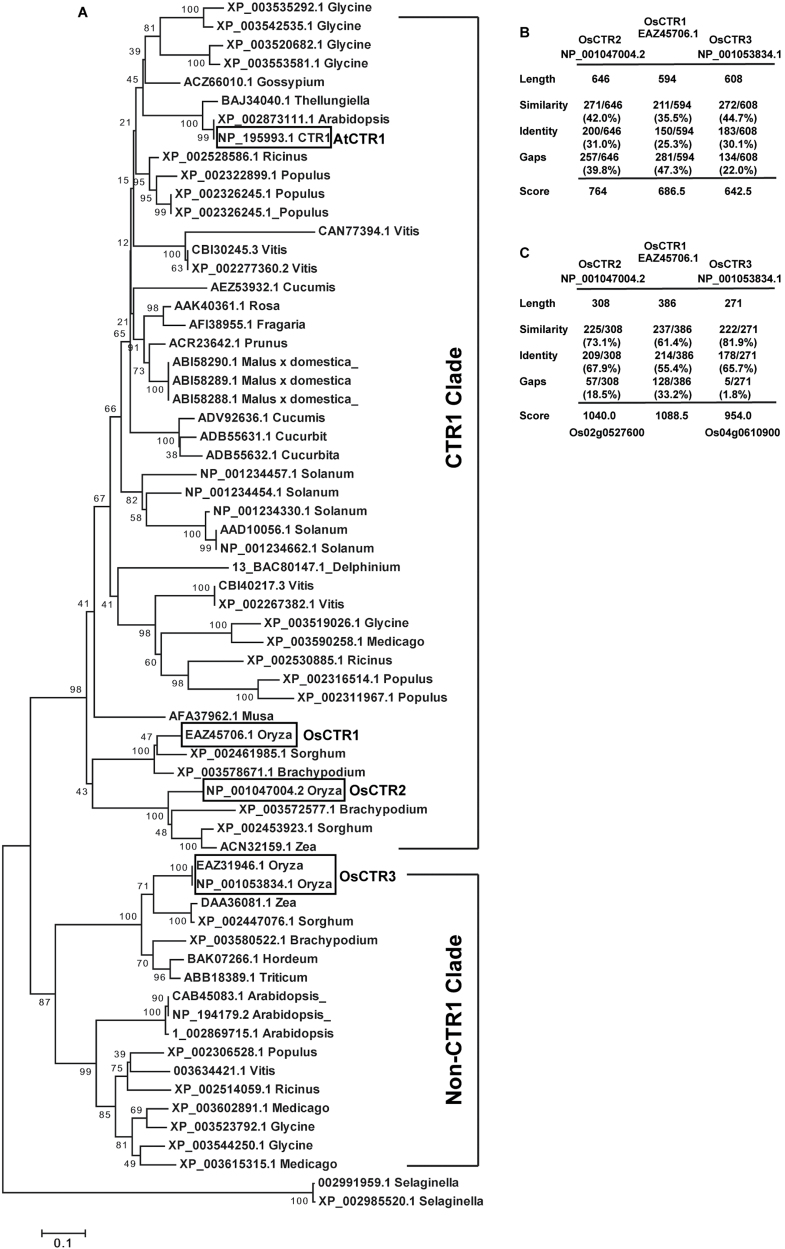

CTR1-related proteins of all plant species except Selaginella were classified into two clades (Fig. 1A). Within the CTR1 clade, Arabidopsis CTR1 and CTR1-related proteins from dicotyledonous plant species were in the same subclade, and OsCTR1/OsCTR2 and CTR1-related proteins from monocotyledonous plants were in another subclade. OsCTR3 was in the non-CTR1 clade, and, consistently, proteins from dicots and monocots were classified into two subclades. The phylogenetic analysis suggested that both OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 are more closely related to CTR1 than OsCTR3. Selaginella CTR1-related proteins appeared ancestral to CTR1-related proteins of seed plants; whether they acquired the ability to mediate ethylene-receptor signalling remains to be determined.

Fig. 1.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of CTR1-related proteins. (A) Phylogenetic tree of plant CTR1-related proteins with accession number and genus names. Arabidopsis CTR1 (AtCTR1) and rice OsCTRs (OsCTR1, OsCTR2, and OsCTR3) are boxed. (B, C) Protein sequence similarity and identity at the N terminus (B) and C terminus (C) of rice OsCTRs compared with that of Arabidopsis CTR1.

The Arabidopsis CTR1 N terminus interacts physically with the ethylene receptors ETR1 and ERS1 to mediate receptor signalling, and an excess amount of the CTR1 N terminus CTR17–560, prevents receptor signalling and results in constitutive ethylene responsiveness. The CTR1 C terminus has a Ser/Thr kinase domain, and the kinase activity is essential for CTR1 functions (Clark et al., 1998; Huang et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2012). Analysed with the EMBOSS Needle Tool (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_needle/), Arabidopsis CTR1 was found to share a higher degree of sequence similarity and identity at the N and C termini with OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 than with OsCTR3 (Fig. 1B, C).

Expression of CTR1p:OsCTR2 complements Arabidopsis ctr1-1 mutation

To evaluate whether OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 have any roles in ethylene-receptor signalling, we ectopically expressed each gene in a ctr1-1 loss-of-function mutant for complementation testing. The OsCTR1 sequence was annotated without mRNA evidence. With the annotation information, efforts to clone the OsCTR1 cDNA by RT-PCR were invalid, and the presence of the OsCTR1 locus remains to be experimentally determined.

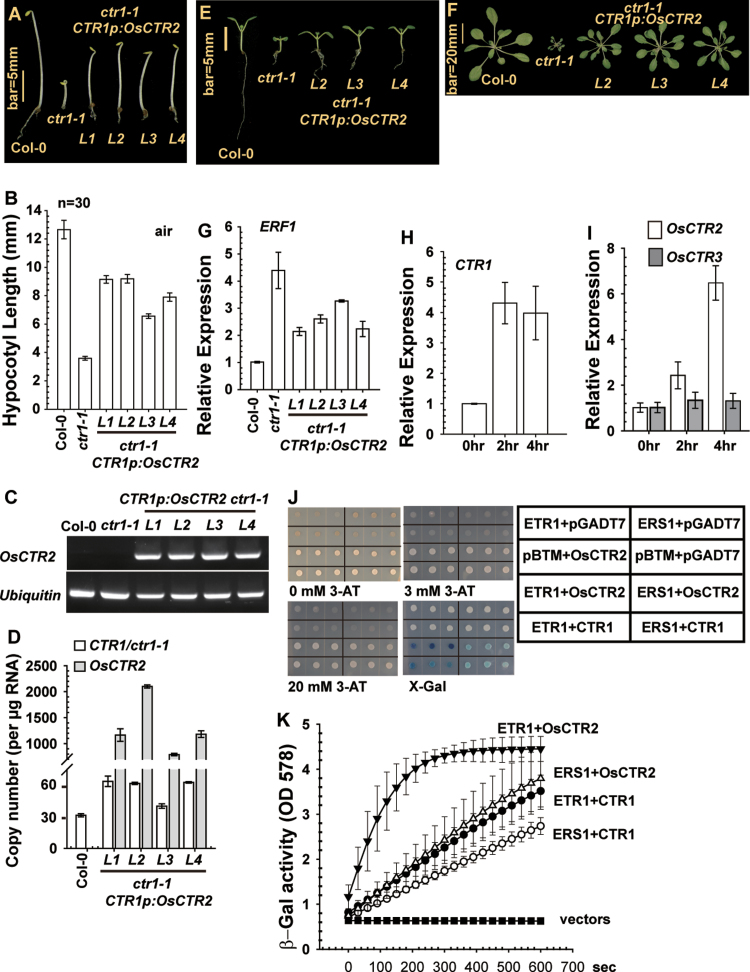

Etiolated, air-grown ctr1-1 seedlings showed a constitutive ethylene response phenotype, with a short hypocotyl and root and an exaggerated apical hook; wild-type (Col-0) seedlings produced a long hypocotyl and root without apical hook formation. Expression of CTR1p:OsCTR2 rescued the ctr1-1 seedling phenotype to a great extent, and the transgenic lines produced a long seedling hypocotyl and root without the apical hook (Fig. 2A). Measurement of seedling hypocotyls showed the same results: ctr1-1 seedling hypocotyls were much shorter than those of ctr1-1 seedlings expressing CTR1p:OsCTR2 without ethylene treatment (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Expression of CTR1p:OsCTR2 complements ctr1-1. (A, B) Phenotype (A) and hypocotyl measurements (B) of etiolated seedlings. L, transformation line. (C, D) Expression of the CTR1p:OSCTR2 transgene in ctr1-1 confirmed by RT-PCR (C) and quantified (D). (E, F) Phenotype of light-grown seedlings (E) and rosettes (F) of ctr1-1 and ctr1-1 expressing CTR1p:OsCTR2. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA level of ERF1. (H, I) Expression of CTR1 in Arabidopsis (H) and of OsCTR2 but not OsCTR3 in rice (I) is ethylene inducible. (J, K) Yeast two-hybrid assay (J) and kinetics of β-galactosidase activity (K) for the interaction between ETR1/ERS1 and the OsCTR2 N terminus. Data are means ±SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. pBTM and pGADT7 are the vectors for the yeast two-hybrid assay.

We confirmed expression of the CTR1p:OsCTR2 transgene in ctr1-1 transformation lines but not the wild type and non-transformed ctr1-1 by RT-PCR (Fig. 2C). To gain knowledge about OsCTR2 expression relative to the endogenous CTR1/ctr1-1, we estimated the copy number of ctr1-1 and OsCTR2 transcripts and found the ctr1-1 and OsCTR2 copy numbers to be higher for transgenic lines than the CTR1 copy number in the wild type (Fig. 2D). CTR1 expression is ethylene inducible, and the higher copy number could be explained by partial suppression of the constitutive ethylene response in the transgenic lines.

The expression of OsCTR2 partially rescued the ctr1-1 ethylene response phenotype. Light-grown ctr1-1 seedlings produced small, compact cotyledons and a short root; consistently, ctr1-1 transgenic lines expressing CTR1p:OsCTR2 produced larger cotyledons and a longer root than ctr1-1 seedlings (Fig. 2E). At the adult stage, expression of the CTR1p:OsCTR2 transgene largely rescued the ctr1-1 growth inhibition phenotype, and the transgenic lines produced a normal rosette, as in wild-type plants (Col-0) (Fig. 2F).

Expression of ERF1 is associated with the degree of ethylene response and can be used as a marker for the ethylene response (Solano et al., 1998; Liu and Wen, 2012a ; Qiu et al., 2012). By setting the ERF1 expression level to 1 in the wild type (Col-0), the ERF1 level in ctr1-1 plants was higher than in ctr1-1 lines expressing CTR1p:OsCTR2 and in wild-type plants (Fig. 2G). Of note, expression of CTR1 in Arabidopsis and OsCTR2 but not OsCTR3 in rice was induced by ethylene (Fig. 2H, I).

The cross-species complementation of ctr1-1 by CTR1p:OsCTR2 indicated that OsCTR2 could physically interact with Arabidopsis ethylene receptors to mediate the receptor signal output. The physical interaction of the ethylene receptors ETR1 and ERS1 with the CTR1 N terminus was shown previously by a yeast two-hybrid assay (Clark et al., 1998; Huang et al., 2003). As expected, the yeast two-hybrid assay revealed a physical interaction of ETR1 (residues 331–729) and ERS1 (residues 130–613) with the OsCTR2 N terminus (residues 1–513), even in the presence of high 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole concentrations as a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product; measurement of β-galactosidase activity to quantify the interaction was consistent with X-gal staining results (Fig. 2J, K).

Rice osctr2 mutant shows several aspects of the constitutive ethylene response phenotype

The results suggested that ectopically expressed OsCTR2 could mediate ethylene-receptor signalling in Arabidopsis. We expected that loss-of-function mutations of OsCTR2 would confer constitutive ethylene responsiveness.

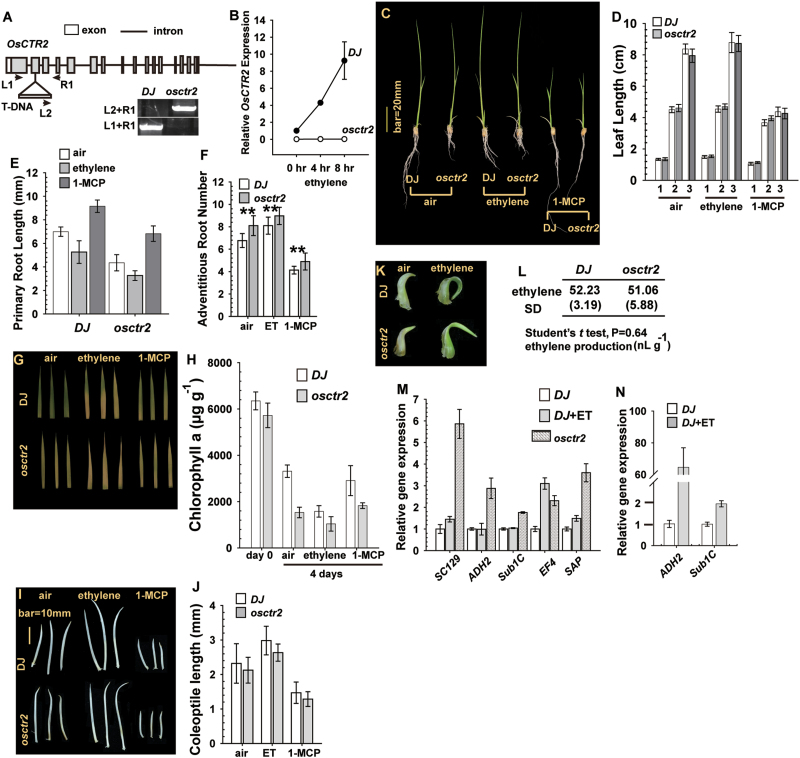

The rice osctr2 mutation with a T-DNA insertion at the second exon of OsCTR2 in the japonica variety DJ background was confirmed by PCR-based genotyping (Fig. 3A). By referencing the OsCTR2 expression in the wild type (DJ) as 1, expression of OsCTR2 in osctr2 was barely detectable and was not ethylene inducible (Fig. 3B). We evaluated whether the osctr2 allele and ethylene treatment would have the same effects on rice. Without ethylene treatment (air), the wild-type DJ and osctr2 rice seedlings were phenotypically similar in height, with a longer root for DJ than for osctr2 seedlings (Fig. 3C). With ethylene treatment for 7 d after germination, the root of both DJ and osctr2 seedlings was shortened. The ethylene blocker 1-MCP substantially inhibited shoot elongation but promoted root elongation in DJ and osctr2 seedlings.

Fig. 3.

Phenotype analysis of osctr2. (A) Diagram of the OsCTR2 gene structure; the T-DNA insertion site in osctr2 is indicated. The positions of the PCR genotyping primers (L1, L2, and R1) are indicated, and the legend shows the PCR genotyping for the wild-type (DJ) and osctr2 mutant. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of relative mRNA levels of OsCTR2 in DJ and osctr2 seedlings. (C, D) Seedling phenotype (C) and leaf length measurement (D) of the DJ and osctr2 plants. Numbers on the x-axis in (D) indicate the order of the seedling leaves (1, first; 2, second; 3, third). (E) Primary root length in DJ and osctr2 seedlings. (F) Number of adventitious roots in the DJ and osctr2 seedlings. **P<0.01 for osctr2 compared with DJ. (G, H) Leaf senescence (G) and chlorophyll a content (H) of DJ and osctr2 seedlings. (I, J) Phenotype (I) and length (J) of etiolated seedling coleoptiles of DJ and osctr2 plants. (K) Coleoptile phenotype of light-grown seedlings. (L) Ethylene evolution of DJ and osctr2 seedlings. Data in are means ±SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P<0.01. (M, N) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of genes in rice seedlings with prolonged (M; 7 d) or short (N; 4h) ethylene treatment (100 µl l–1). Data are means ±SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

We showed previously that ethylene treatment promoted elongation of the third leaf of the wild-type ZH11 variety (Zhang et al., 2012). Measurement of individual leaves of DJ and osctr2 showed that ethylene treatment had minor effects on leaf elongation, whereas 1-MCP treatment to block ethylene signalling reduced elongation of the third leaf to a great extent (Fig. 3D). Without ethylene treatment, DJ seedlings produced a much longer primary root than did osctr2 seedlings. Ethylene treatment inhibited the primary root elongation in DJ and osctr2 seedlings, with a shorter primary root in osctr2 than DJ (Fig. 3E). 1-MCP treatment promoted primary root elongation in both DJ and osctr2 seedlings, and osctr2 seedlings produced a much shorter primary root than DJ seedlings (Student’s t-test for a paired comparison between DJ and osctr2, P<0.01).

Ethylene promotes adventitious root development in the japonica ZH11 variety (Zhang et al., 2012). Consistently, with ethylene treatment, the adventitious root number was increased in DJ and osctr2 seedlings, with more adventitious roots in osctr2 than in DJ seedlings (Fig. 3F). Without ethylene, DJ seedlings produced fewer adventitious roots than osctr2 seedlings. Treatment with the ethylene blocker 1-MCP reduced the adventitious root number to a great extent, but osctr2 still produced more adventitious roots than DJ (Student’s t-test for paired comparisons between DJ and osctr2 in each treatment, P<0.01).

Other aspects of the ethylene response phenotype were scored for osctr2. Rice leaf segments undergo senescence following ethylene treatment (Kao and Yang, 1983; Zhang et al., 2012). Without ethylene treatment, osctr2 leaves showed a much stronger senescence phenotype than DJ leaves (Fig. 3G). Ethylene treatment promoted leaf senescence in both genotypes, with a stronger senescence phenotype in osctr2 than in DJ leaves. 1-MCP treatment delayed the senescence in DJ but not in osctr2 plants. The degree of leaf senescence was quantified by measuring chlorophyll a content. Both DJ and osctr2 leaves had a similar chlorophyll a content before treatment (Fig. 3H). The chlorophyll a content was much higher in DJ than osctr2 leaves 4 d after detachment in air. Consistently, ethylene treatment decreased the chlorophyll a content in DJ and osctr2 leaves, with more chlorophyll a content in DJ than in osctr2 leaves. With 1-MCP treatment, DJ showed a much higher chlorophyll a content than osctr2.

Ethylene has been shown to promote coleoptile elongation in etiolated rice seedlings (Satler and Kende, 1985; Zhang et al., 2012). The coleoptile of both DJ and osctr2 seedlings was of similar length, and ethylene promoted but 1-MCP prevented coleoptile elongation (Fig. 3I, J). Light-grown rice seedlings produce a relatively straight coleoptile, and ethylene treatment promotes coleoptile curvature and elongation (Zhang et al., 2012). Without ethylene treatment, both DJ and osctr2 seedlings produced a relatively straight coleoptile but an exaggerated coleoptile curvature on ethylene treatment (Fig. 3K). Of note, the phenotype differences between DJ and osctr2 were not due to differential ethylene production; both produced a similar amount of ethylene (Fig. 3L; Student’s t-test, P=0.64).

We evaluated the degree of the ethylene response in DJ and osctr2 by measuring the expression of ethylene-inducible genes. The expression of SUB1C, SC129, and ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE2 (ADH2) was shown previously to be induced by ethylene in the ZH11 variety (Fukao et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2012). EARLY FLOWERING4 (EF4; Os11g0621500) and SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN (SAP; Os02g0324700) were ethylene inducible as identified by an unpublished microarray analysis. qRT-PCR revealed that, with ethylene treatment, the expression of these genes was increased to various levels in DJ seedlings and air-grown osctr2 (Fig. 3M, N). Of note, levels of ADH2 and SUB1C were not altered in DJ seedlings with prolonged ethylene treatment (7 d; Fig. 3M) but were induced with short ethylene treatment (4h; Fig. 3N).

These results suggested that, without exogenous ethylene treatment, osctr2 seedlings showed several, but not all, aspects of the ethylene response phenotype and that these aspects were stronger than in DJ plants. Conceivably, a low basal level of ethylene responsiveness could be sufficient to maximize the elongation of seedling leaves and coleoptiles in the DJ variety, for minor effects of ethylene treatment on seedling leaf and coleoptile elongation. The expression of ADH2 and SUB1C could be attenuated after prolonged treatment with a high ethylene concentration (100 µl l–1).

OsCTR21–513 overexpression results in various aspects of the constitutive ethylene response phenotype

The Arabidopsis ETR1 ethylene receptor mediates the ethylene-receptor signal output to CTR1 via interaction of the CTR1 N terminus and the ETR1 HK domain (Clark et al., 1998). Excess CTR1 N terminus (residues 7–560) prevents receptor signalling, and the CTR1 7–560 overexpressor CTR1Nox produces a constitutive ethylene response phenotype (Huang et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2012). Involvement of OsCTR2 in the ethylene-receptor signalling could be evaluated by determining whether overexpression of the OsCTR2 N terminus also results in a constitutive ethylene response.

35S:OsCTR2 1–513, which encodes the OsCTR2 N terminus, was transformed into the japonica rice variety ZH11. Expression of the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgene in four representative transgenic lines was confirmed by qRT-PCR, and lines L3, L36, and L42 were selected for further study because of their differential OsCTR2 1–513 levels (Fig. 4A). The wild type (ZH11) showed a shorter seedling and longer roots than the transformation lines (Fig. 4B). Measurement of primary roots gave the same results: the primary root was longer for ZH11 than for the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines (Scheffe’s test, P<10–8). The primary root was shorter in ZH11 with than without ethylene treatment (Scheffe’s test, P=0.0141; Fig. 4C). We showed previously that ethylene treatment increases the number of adventitious roots. As expected, without ethylene treatment, ZH11 seedlings produced fewer adventitious roots than the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines and ethylene-treated ZH11 seedlings (Scheffe’s test, P<10–18). The number of adventitious roots was similar for ethylene-treated ZH11 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines (Scheffe’s test, P=0.04–0.588; Fig. 4D).

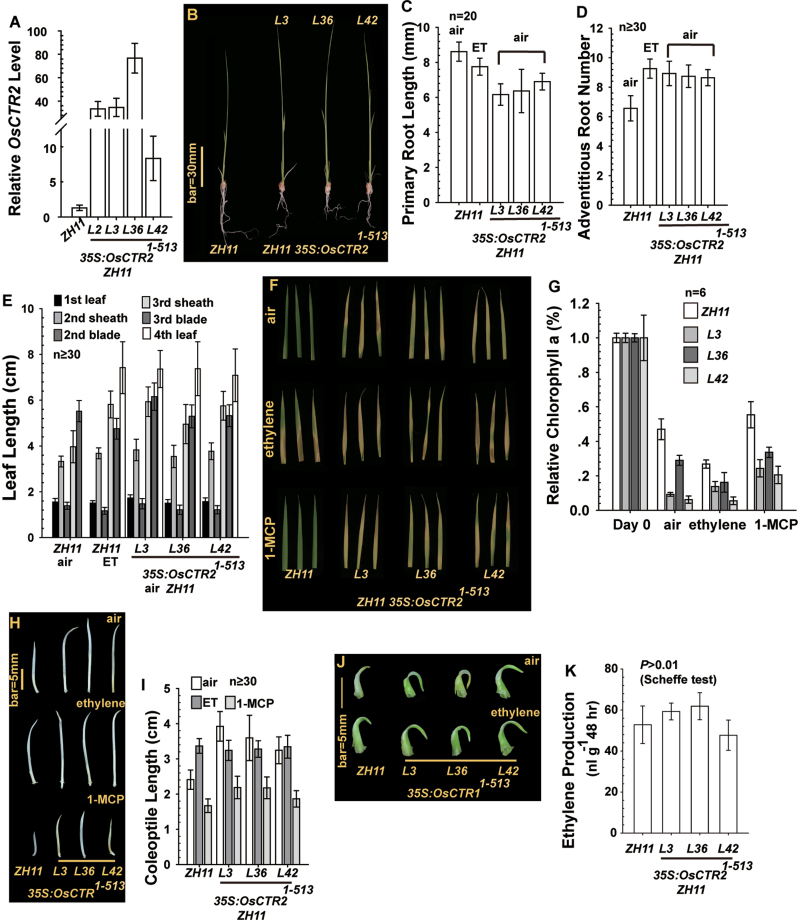

Fig. 4.

Expression of 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 confers a constitutive ethylene response in rice. (A–E) qRT-PCR analysis of OsCTR2 mRNA level (A), seedling phenotype (B), primary root length (C), adventitious root number (D), and seedling leaf length (E) of the wild type (ZH11) and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines. (F–I) Leaf senescence phenotype (F), relative chlorophyll a content (G), coleoptile phenotype (H), and coleoptile length (I) of the wild type (ZH11) and transgenic lines. (J) Coleoptile phenotype of light-grown seedlings. (K) Ethylene evolution in the wild-type (ZH11) and transgenic lines. Data are means ±SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. L, transformation line. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Ethylene treatment promoted sheath elongation of the third leaf in ZH11 seedlings (Zhang et al., 2012). As expected, third-leaf sheaths of ethylene-treated ZH11 seedlings and air-grown 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines were 1–2cm longer than those of non-treated ZH11 seedlings (Scheffe’s test, P<10–6; Fig. 4E). Consistent with our previous finding that ethylene promoted the growth of the fourth leaf (Zhang et al., 2012), ethylene-treated ZH11 and air-grown transgenic lines but not air-grown ZH11 produced four leaves (Fig. 4E).

These results suggested that overexpression of the OsCTR2 N terminus results in a constitutive ethylene response. Conceivably, leaf senescence in the transgenic lines could occur without ethylene treatment. ZH11 seedling leaf segments showed a mild senescence phenotype 4 d after detachment in air, and 1-MCP treatment prevented the senescence phenotype (Fig. 4F). Ethylene treatment for 4 d promoted the senescence progression, and ZH11 leaf segments showed a strong senescence phenotype. For the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic rice lines, the leaf segments showed a strong senescence phenotype 4 d after detachment in air, and 1-MCP did not prevent the senescence phenotype. With ethylene treatment for 4 d, the transgenic lines produced the same senescence phenotype as with no treatment (Fig. 4F). To quantify the degree of leaf senescence, we measured relative chlorophyll a content after the senescence test. By setting the chlorophyll a content to 1 in leaves before treatment, leaf segments of the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic rice lines showed much lower relative chlorophyll a content than ZH11 plants in all treatments (Fig. 4G). 1-MCP treatment attenuated the chlorophyll a reduction in ZH11 leaf segments, and the effect was minor in leaves of transgenic lines.

Ethylene promotes the coleoptile elongation of etiolated rice seedlings (Satler and Kende, 1985; Zhang et al., 2012). As expected, etiolated ZH11 seedlings produced a longer coleoptile with than without ethylene treatment, and etiolated seedlings of the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines produced a longer coleoptile than ZH11 seedlings; 1-MCP treatment reduced the coleoptile length, and ZH11 produced a much shorter coleoptile than the transgenic lines (Fig. 4H, I). Grown under light, ZH11 seedlings produced a relatively straight coleoptile compared with seedlings with ethylene treatment; consistently, 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines produced a coleoptile with curvature, regardless of ethylene treatment (Fig. 4J). ZH11 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines produced the same amount of ethylene (Scheffe’s test, P>0.01; Fig. 4K). Thus, the 35S: OsCTR2 1–513 transgene facilitated a constitutive ethylene response without increasing ethylene production.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused OsCTR2 co-localizes with the ER marker ER-rk

Previous studies of the subcellular localization of Arabidopsis CTR1 and tomato CTR1-related proteins revealed their localization at the ER (Gao et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2008). We studied the subcellular localization of OsCTR2 with GFP-fused OsCTR2.

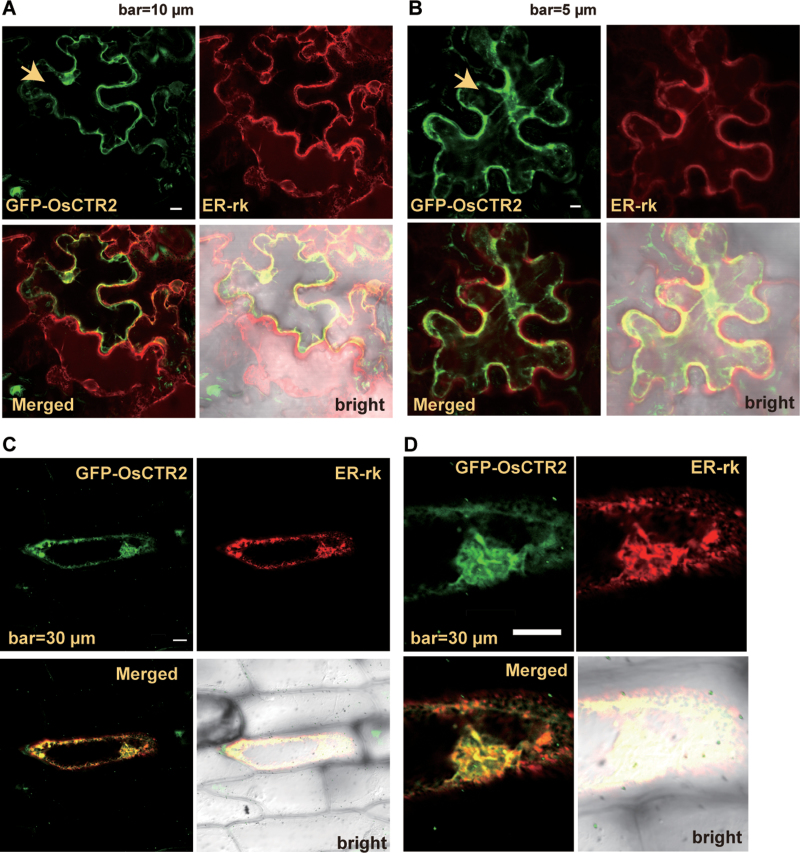

The transgene encoding the full-length GFP-fused OsCTR2 was transformed into Arabidopsis expressing the ER marker ER-rk (Nelson et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the resulting transformants did not show fluorescence by ER-rk, possibly because of co-suppression. We determined whether the two fluorescent proteins could be co-expressed in tobacco cells by infiltration with a mix of Agrobacterium containing both clones. The two proteins did not express equally, and we selected only cells expressing both proteins at a similar level. Green (GFP–OsCTR2) and red (ER-rk) fluorescence was observed mainly surrounding the nucleus, at the cell edge of tobacco cells, with an uneven, discrete pattern (Fig. 5A), and the ER network was also observed (Fig. 5B). To obtain other evidence supporting localization of OsCTR2 at the ER, GFP–OsCTR2 was transiently co-expressed with ER-rk in onion epidermal cells by particle bombardment. Consistently, the fluorescence of GFP–OsCTR2 and ER-rk co-localized (Fig. 5C). The nucleus was surrounded by GFP–OsCTR2 and ER-rk (Fig. 5D), which is consistent with the close association of the ER with the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope.

Fig. 5.

Subcellular localization of GFP–OsCTR2. Fluorescence of GFP–OsCTR2 (green) and ER-rk (red) in tobacco (A, B) and onion epidermal (C, D) cells. The cell for the co-localization study is indicated with an arrowhead in (A) and (B).

Evaluation of ethylene effects on agronomic traits involving yield

The growth conditions for rice are highly demanding, and evaluating ethylene effects on agronomic traits with prolonged ethylene treatment without compromising rice growth is technically difficult. With the higher degree of ethylene responsiveness in osctr2 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines than in the wild type, we evaluated the effects of the constitutive ethylene response, which could mimic a prolonged ethylene treatment, on yield-related agronomic traits.

Both DJ and osctr2 seedlings produced a panicle of the same length (Fig. 6A; Student’s t-test, P=0.88); consistently, ZH11 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines produced a panicle of the same length (Fig. 6A; Scheffe’s test, P>0.039). DJ plants were slightly taller than osctr2 plants (Fig. 6B; Student’s t-test, P<10–5); differences in plant height between ZH11 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines were minor, and the ZH11, L2, and L42 lines were the same height (Fig. 6B; Scheffe’s test, P>0.026). Effective tillers produce panicles, and the number of effective tillers is an important trait determining rice yield. DJ plants produced fewer effective tillers than osctr2 plants (Fig. 6C; Student’s t-test, P=0.002); consistently, ZH11 produced fewer effective tillers than the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines (Fig. 6C; Scheffe’s test, P<0.01). The constitutive ethylene response could increase the number of effective tillers. The panicle neck length (or the upper-most internode length) is an important trait determining rice plant height. The panicle neck length of DJ and osctr2 plants was identical (Fig. 6D; Student’s t-test, P=0.89), whereas that for ZH11 was 2–3.7cm longer than for the transgenic lines (Fig. 6D; Scheffe’s test, P<10–4). Grain weight is also an important trait that determines yield. We measured the weight of 300 grains; those of DJ plants had a slightly greater weight than those of osctr2 plants (Fig. 6E; Student’s t-test, P<10–4) and the 300-grain weight of ZH11 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines was identical (Fig. 6E; Scheffe’s test, P>0.04).

Overexpression of the ethylene receptor-like gene OsETR2 results in delayed flowering in ZH11 and reduced sensitivity to ethylene, and alterations in the ethylene response may result in the delayed flowering phenotype (Wuriyanghan et al., 2009). We determined whether osctr2 and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 expression affected heading time. Normally, the heading of field-grown rice plants is not synchronous; we scored the heading status within 72–80 d post-planting. At day 72, DJ plants (60%) showed early heading compared with osctr2 plants (6.7%). At day 74, heading was complete in DJ plants but not until day 80 in osctr2 plants (Fig. 6F). At day 72, ZH11 (85.5%) also showed early heading compared with the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines (7.9–28.9%). At days 75 and 76, heading was complete for ZH11 but not until day 79 for the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines (Fig. 6G).

We showed an association of an increase in effective tiller number and delayed heading with osctr2 (in DJ) and 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 expression (in ZH11). Elevation in the degree of the constitutive ethylene response may be associated with these traits.

Discussion

Arabidopsis CTR1 is a key component mediating the ethylene-receptor signal output to suppress ethylene responses (Ju et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2012). Our phylogenetic analysis suggested that rice has two CTR1-related genes: OsCTR2 and the annotated OsCTR1. Without mRNA evidence for OsCTR1, the presence of the OsCTR1 locus and the OsCTR1 protein sequence remain to be determined. Our data support the suggestion that OsCTR2 can mediate ethylene-receptor signalling in rice.

Several lines of evidence suggest that OsCTR2 is not the only component that can mediate the ethylene-receptor signal output. The mutant osctr2 showed a similar leaf growth phenotype to the wild type (DJ), with or without treatment with ethylene and its blocker 1-MCP. The ethylene-promoted coleoptile growth and curvature phenotype was also similar between DJ and osctr2 plants, and 1-MCP treatment inhibited coleoptile elongation in both genotypes. Therefore, the ethylene-induced leaf and coleoptile growth phenotype could be independent of OsCTR2. However, ethylene treatment and the osctr2 allele had the same effects on primary root growth, adventitious root development, and leaf senescence, so these ethylene-induced growth alterations involved OsCTR2. The involvement of OsCTR2 in ethylene signalling appeared to be tissue specific.

Although leaf and coleoptile growth was not affected by osctr2 at the seedling stage, 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 expression had the same effects as ethylene treatment on these phenotypes and other aspects of ethylene-induced alteration in growth. An excess amount of the CTR1 N terminus prevents ethylene-receptor signalling, and thus the ethylene response is relieved from suppression (Huang et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2012). We hypothesized that 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 expression could result in a gain of function to prevent ethylene-receptor signalling in ZH11, such that various aspects of the ethylene response phenotype were observed in 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines.

Our results suggested that OsCTR2 is not the only component that mediates the ethylene-receptor signal output in rice. The putative OsCTR1 is highly related to CTR1 and could have a role in ethylene-receptor signalling. OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 could be expressed differentially in various tissues because osctr2 showed several but not all aspects of the ethylene-induced growth alteration in a tissue-specific manner. Alternatively, OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 could be functionally divergent to suppress various aspects of the ethylene response. The latter scenario suggests the presence of distinct modules that could mediate ethylene-receptor signalling. Interestingly, the use of modules with distinct and overlapping functions in ethylene signalling has also been found in tomato. Arabidopsis RTE1 promotes the ethylene-receptor ETR1 signal output. In tomato, the ethylene response is differentially controlled by two RTE1-related proteins: GREEN-RIPE and GREEN-RIPE LIKE1 (Ma et al., 2012). Moreover, in Arabidopsis, ethylene-receptor signalling can be mediated by a pathway independent of CTR1 (Qiu et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2012). Ethylene-receptor signalling in rice could be also mediated by a pathway independent of CTR1-related proteins. The mediation of ethylene-receptor signalling by distinct modules or to alternative signalling pathways implies a multilevel regulation of ethylene signalling.

CTR1 does not have any predicted transmembrane helices and is co-fractionated with the ER membrane (Gao et al., 2003). A subcellular localization study involving yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged tomato CTR1-related proteins suggests that each N terminus (LeCTR-N) of the three tomato CTR1-related proteins LeCTR1, LeCTR3, and LeCTR4 interacts with the ethylene receptor NEVER-RIPE (NR) in onion epidermal cells. Without NR co-expression, the YFP–LeCTR-N fusions were localized to the cytoplasm and nucleus but not to the ER (Zhong et al., 2008). The subcellular localization of a fluorescent protein-tagged full-length CTR1-related protein remains to be determined. Although we were unable to directly show the subcellular localization of GFP–OsCTR2 in rice cells, we showed a co-localization of GFP–OsCTR2 in onion and tobacco cells with the ER marker ER-rk. Moreover, complementation of Arabidopsis ctr1-1 by CTR1p:OsCTR2 and the physical interaction between ETR1/ERS1 and the OsCTR2 N terminus support the suggestion that OsCTR2 is localized at the ER by associating with ethylene receptors. In contrast to the localization of YFP–LeCTR-Ns to the cytoplasm and nucleus in onion cells, GFP–OsCTR2 was not observed in the nucleus. The localization of YFP–LeCTR-Ns to the nucleus could be an artefact; alternatively, LeCTRs could shuttle between the ER and the nucleus, but the functional significance of this needs to be addressed.

A few studies of ethylene effects on growth in japonica varieties were conducted mainly with the ethylene precursor ACC and the ethylene releaser ethephon to replace ethylene treatment (Jun et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2006; Wuriyanghan et al., 2009). ACC is rapidly consumed after its application, and ethephon hydrolyses into ethylene and strong acids. Of note, ethylene production cannot be controlled experimentally with ACC and ethephon, and for ethylene effects that require a prolonged response window, ACC and ethephon are not ideal as replacements for ethylene (Lavee and Martin, 1981; Zhang and Wen, 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Silver is an effective blocker of the ethylene response, and silver treatment results in abnormal root growth in rice seedlings, with accumulation of a dark-brown unknown compound. Whether silver can be an ideal ethylene blocker without affecting normal rice growth needs to be evaluated.

Evaluating the effects of ethylene on agronomic traits of rice plants is technically difficult. With the constitutive ethylene response, the effect of prolonged ethylene treatment on agronomic traits related to yield could be evaluated by comparing phenotypic differences between the wild-type (DJ) and osctr2 plants and between ZH11 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines. We found two agronomic traits related to yield that were altered with ethylene: both osctr2 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines produced more effective tillers and showed delayed flowering compared with the wild type (DJ and ZH11). With more effective tillers, rice yield could be increased.

The effect of ethylene on rice growth and development inferred from osctr2 and the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 transgenic lines was consistent with the effect of treatment with ethylene and 1-MCP and that inferred from studies of ethylene-insensitive 35S:OsRTH1 lines (Zhang et al., 2012). The isolation of osctr2, together with the 35S:OsCTR2 1–513 lines and 35S:OsRTH1 lines that we obtained previously should facilitate future studies of the underlying mechanisms of the ethylene effect on various aspects of rice growth and development in response to external and internal cues.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online

Supplementary data S1. Primer sets for cloning and qRT-PCR.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB100700 and 2012AA10A302-2), the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31123006, 31200217, and 31070249), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-EW-J-12). The osctr2 mutant was from Dr Gyheung An (Kyung Hee University, Korea).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 1-MCP

1-methylcyclopropene

- ACC

1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

- X-gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- Alexander L, Grierson D. 2002. Ethylene biosynthesis and action in tomato: a model for climacteric fruit ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany 53, 2039–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Granell A. 1995. A putative vacuolar processing protease is regulated by ethylene and also during fruit ripening in Citrus fruit. Plant Physiology 109, 541–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JP, Badruzsaufari E, Schenk PM, Manners JM, Desmond OJ, Ehlert C, Maclean DJ, Ebert PR, Kazan K. 2004. Antagonistic interaction between abscisic acid and jasmonate-ethylene signaling pathways modulates defense gene expression and disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 3460–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KL, Larsen PB, Wang X, Chang C. 1998. Association of the Arabidopsis CTR1 Raf-like kinase with the ETR1 and ERS ethylene receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 95, 5401–5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J. 2008a. Ethylene—a key regulator of submergence responses in rice. Plant Science 175, 43–51 [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J. 2008b. Submergence tolerance conferred by Sub1A is mediated by SLR1 and SLRL1 restriction of gibberellin responses in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105, 16814–16819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Xu K, Ronald PC, Bailey-Serres J. 2006. A variable cluster of ethylene response factor-like genes regulates metabolic and developmental acclimation responses to submergence in rice. Plant Cell 18, 2021–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Chen YF, Randlett MD, Zhao XC, Findell JL, Kieber JJ, Schaller GE. 2003. Localization of the Raf-like kinase CTR1 to the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis through participation in ethylene receptor signaling complexes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, 34725–34732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Nagai K, Furukawa S, et al. 2009. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature 460, 1026–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Meyerowitz EM. 1998. Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana . Cell 94, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li H, Hutchison CE, Laskey J, Kieber JJ. 2003. Biochemical and functional analysis of CTR1, a protein kinase that negatively regulates ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis . The Plant Journal 33, 221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JS, Lee S, Jung KH, et al. 2000. T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for functional genomics in rice. The Plant Journal 22, 561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong DH, An S, Park S, et al. 2006. Generation of a flanking sequence-tag database for activation-tagging lines in japonica rice. The Plant Journal 45, 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Yoon GM, Shemansky JM, et al. 2012. CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 19486–19491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun SH, Han MJ, Lee S, Seo YS, Kim WT, An G. 2004. OsEIN2 is a positive component in ethylene signaling in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 45, 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Seo YS, Walia H, Cao P, Fukao T, Canlas PE, Amonpant F, Bailey-Serres J, Ronald PC. 2010. The submergence tolerance regulator Sub1A mediates stress-responsive expression of AP2/ERF transcription factors. Plant Physiology 152, 1674–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao CH, Yang SF. 1983. Role of ethylene in the senescence of detached rice leaves. Plant Physiology 73, 881–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavee S, Martin GC. 1981. Ethylene evolution following treatment with 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid and ethephon in an in vitro olive shoot system in relation to leaf abscission. Plant Physiology 67, 1204–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wen CK. 2012a. Arabidopsis ETR1 and ERS1 differentially repress the ethylene response in combination with other ethylene receptor genes. Plant Physiology 158, 1193–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wen CK. 2012b. Cooperative ethylene receptor signaling. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7, 1042–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Du W, Brandizzi F, Giovannoni JJ, Barry CS. 2012. Differential control of ethylene responses by GREEN-RIPE and GREEN-RIPE LIKE1 provides evidence for distinct ethylene signaling modules in tomato. Plant Physiology 160, 1968–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Wang S, Jia Q, Wu P. 2006. OsEIL1, a rice homolog of the Arabidopsis EIN3 regulates the ethylene response as a positive component. Plant Molecular Biology 61, 141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A. 2007. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. The Plant Journal 51, 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H, Shen Z, Huang SS, Schmitz RJ, Urich MA, Briggs SP, Ecker JR. 2012. Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science 338, 390–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Xie F, Yu J, Wen CK. 2012. Arabidopsis RTE1 is essential to ethylene receptor ETR1 amino-terminal signaling independent of CTR1. Plant Physiology 159, 1263–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika H, Okamoto M, Miyoshi K, et al. 2007. Ethylene promotes submergence-induced expression of OsABA8ox1, a gene that encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylase in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology 48, 287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satler SO, Kende H. 1985. Ethylene and the growth of rice seedlings. Plant Physiology 79, 194–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker J. 1998. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes & Development. 12, 3703–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28, 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Knaap E, Kim JH, Kende H. 2000. a novel gibberellin-induced gene from rice and its potential regulatory role in stem growth. Plant Physiology 122, 695–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuriyanghan H, Zhang B, Cao WH, et al. 2009. The ethylene receptor ETR2 delays floral transition and affects starch accumulation in rice. Plant Cell 21, 1473–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Liu Q, Wen CK. 2006. Receptor signal output mediated by the ETR1 N terminus is primarily Subfamily I receptor dependent. Plant Physiology 142, 492–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Qiu L, Wen CK. 2012. Possible modulation of Arabidopsis ETR1 N-terminal signaling by CTR1. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7, 1243–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Xu X, Fukao T, Canlas P, Maghirang-Rodriguez R, Heuer S, Ismail AM, Bailey-Serres J, Ronald PC, Mackill DJ. 2006. Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature 442, 705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Hu W, Wen CK. 2010. Ethylene preparation and its application to physiological experiments. Plant Signaling & Behavior 5, 453–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wen CK. 2010. Preparation of ethylene gas and comparison of ethylene responses induced by ethylene, ACC, and ethephon. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhou X, Wen CK. 2012. Modulation of ethylene responses by OsRTH1 overexpression reveals the biological significance of ethylene in rice seedling growth and development. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 4151–4164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Lin Z, Grierson D. 2008. Tomato ethylene receptor–CTR interactions: visualization of NEVER-RIPE interactions with multiple CTRs at the endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 965–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Liu Q, Xie F, Wen CK. 2007. RTE1 is a golgi-associated and ETR1-dependent negative regulator of ethylene responses. Plant Physiology 145, 75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.