Abstract

Dietary ferulic acid (FA), a significant antioxidant substance, is currently the subject of extensive research. FA in cereals exists mainly as feruloylated sugar ester. To release FA from food matrices, it is necessary to cleave ester cross-linking by feruloyl esterase (FAE) (hydroxycinnamoyl esterase; EC 3.1.1.73). In the present study, the FAE from a human typical intestinal bacterium, Lactobacillus acidophilus, was isolated, purified, and characterized for the first time. The enzyme was purified in successive steps including hydrophobic interaction chromatography and anion-exchange chromatography. The purified FAE appeared as a single band in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with an apparent molecular mass of 36 kDa. It has optimum pH and temperature characteristics (5.6 and 37°C, respectively). The metal ions Cu2+ and Fe3+ (at a concentration of 5 mmol liter−1) inhibited FAE activity by 97.25 and 94.80%, respectively. Under optimum pH and temperature with 5-O-feruloyl-l-arabinofuranose (FAA) as a substrate, the enzyme exhibited a Km of 0.0953 mmol liter−1 and a Vmax of 86.27 mmol liter−1 min−1 mg−1 of protein. Furthermore, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified FAE was found to be A R V E K P R K V I L V G D G A V G S T. The FAE released FA from O-(5-O-feruloyl-α-l-arabinofuranosyl)-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose (FAXX) and FAA obtained from refined corn bran. Moreover, it released two times more FA from FAXX in the presence of added xylanase.

Ferulic acid (FA) is a common component in plant cell walls and shows strong antioxidant potential by its radical-scavenging ability (16). In recent years, the results of many in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that FA prevents low-density lipoprotein from oxidation (2, 27, 29, 31), exhibits inhibitory effects on tumor promotion (1, 17), and protects against certain chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease and some cancers (6, 20, 21, 37).

In cereals, FA is mainly ester linked with arabinose or galactose residues (which constitute side chains of cell wall polysaccharides) (15, 18, 19, 28, 34, 38). Wende et al. showed that FA was released from 2-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(5-O-feruloyl)-l-arabinose by rat gut microorganisms quite quickly and presumed that feruloyl esterase (FAE) would be produced by microorganisms, with high-level activity which is closely related to the release (40). Subsequently, other in vitro observations confirmed the existence of FAE in animal and human intestines (3, 23). These results suggest that FAE plays an important role in releasing free FA from different feruloylated forms in foodstuff in the gut.

Although FAEs from some eukaryotic cells (4, 7, 11, 12, 14, 22, 26, 39) and from only one prokaryotic cell (13) have been purified and characterized to date, there is no information about FAE from intestinal bacteria. It is reported that FAEs from various sources show different properties with respect to such characteristics as optimal temperature and optimal pH. Therefore, it is necessary to purify the FAE from human gut bacteria to further study the mechanism of release of FA from complex food matrices in vitro. Nishizawa et al. studied the FAE activities of typical intestinal bacteria and found that among the intestinal bacteria tested, Lactobacillus acidophilus exhibited the highest level of activity with respect to feruloylated arabinose ester (30).

Some investigations indicate that the presence of xylanase enhances FAE activity. In most of these studies, however, destarched wheat bran was used as a substrate; these experiments could not supply sufficiently detailed information to explain the releasing mechanism of dietary FA and the interaction between xylanase and FAE to release FA. Therefore, an FAE from a typical intestinal bacterium (L. acidophilus) was purified to homogeneity, the enhancement of the FAE activity by the presence of a xylanase was studied with feruloylated sugar esters as substrates, and the N-terminal amino acid sequence was identified; the results are presented in this paper.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

(i) Chemicals.

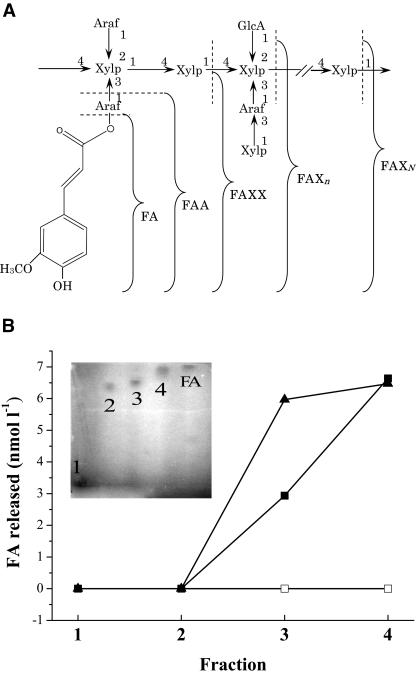

The feruloylated sugar esters FAXN (feruloyl-arabinoxylan), FAXn (feruloyl-arabinoxylan with a degree of polymerization of xylopyranose less than that of FAXN), FAXX [O-(5-O-feruloyl-α-l-arabinofuranosyl)-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose], and FAA (5-O-feruloyl-l-arabinofuranose) (see Fig. 5) were prepared from refined corn bran (RCB; Nihon Shokuhin Kako Co., Ltd.) by acid hydrolysis, gel filtration chromatography (Sephadex LH-20; Pharmacia), thin-layer chromatography, and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis as described previously (19, 31, 32). The quantification was done by the Folin-Ciocalteu method (36).

FIG. 5.

Release of FA from the feruloylated sugar esters by the purified FAE from L. acidophilus. (A) Schematic structure of the feruloylated compounds from RCB. Araf, arabinofuranose; GlcA, glucuronic acid; Xylp, xylopyranose. (B) Thin-layer chromatography of the feruloylated compounds from RCB (inset). 1, FAXN; 2, FAXn; 3, FAXX; 4, FAA. The released FA was measured using an assay mixture in which only FAE (▪), only xylanase (□), or both FAE and xylanase (▴) were used.

FA and other chemicals (analytical or high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC] grade) were from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan) unless otherwise indicated.

(ii) Organism and growth conditions.

L. acidophilus (IFO 13951), which was purchased from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (Osaka, Japan), was grown in medium containing 5 g of polypeptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 1 g of MgSO4 • 7H2O, and 0.5 g of Tween 80 in 1 liter of distilled water without aeration and agitation with 5 g of glucose and 2 g of lactose as a carbon source at 37°C for 60 h as recommended by the manufacturer.

(iii) Enzyme purification. (a) Extraction of enzyme from bacteria.

Cells were harvested from culture medium by centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. For each gram of cell pellets, 10 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) including 0.9% NaCl and 2 mM (±)-dithiothreitol (DTT) and then 0.0013 g of lysozyme (from chicken egg white) were added. After incubation with shaking in a water bath was performed at 37°C for 15 min, ultrasonification was carried out on ice for 60 s to disrupt cell walls. The cell wall debris was removed by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant obtained was used as crude extract. Ammonium sulfate was added slowly to the crude extract with stirring to give 80% saturation. After treatment overnight at 4°C, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation (7,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C).

(b) HIC.

The precipitate was dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) including 1 mmol of EDTA liter−1 and 1 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1. The solution was applied to a hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) column (TSKgel Phenyl-5PW; Tosoh) (7.5-mm inside diameter [i.d.] by 7.5-cm length) connected to an HPLC system (model L-6200; Hitachi). The column had previously been equilibrated at a flow rate of 0.8 ml min−1 with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mmol of EDTA liter−1 and 1 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1. The elution of enzyme was performed by using a linear gradient of 1 to 0 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1 in the same buffer in 60 min. Fractions of 1.6 ml each were collected and assayed for FAE activity.

The highly active fractions were pooled and concentrated by vacuum evaporation at 30°C for 150 min. As stated above, the concentrated enzymatic solution was reloaded on the HIC column (the same as described above) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0.8 to 0 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1 in the same buffer in 60 min. Fractions of 1.6 ml each were collected.

(c) IEC.

After vacuum evaporation (at 30°C for 120 min) of pooled highly active fractions from the second HIC procedure, the buffer was changed to 20 mmol of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) liter−1 containing 1 mmol of EDTA liter−1 by ultrafiltration (Centricon YM-10; Millipore) (10,000 molecular weight [MW] cutoff) at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C following the instructions of the manufacturer. The FAE was further fractionated on an anion-exchange chromatography (IEC) column (TSKgel DEAE-5PW; Tosoh) (7.5-mm i.d. by 7.5-cm length) which had been preequilibrated with 20 mmol of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) liter−1 containing 1 mmol of EDTA liter−1. The elution was achieved by using a linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 mol of NaCl liter−1 in 20 mmol of Tris-HCl buffer liter−1 containing 1 mmol of EDTA liter−1 at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1 in 60 min. Fractions (1 ml each) were collected. The fraction containing high-level FAE activity was used as the purified enzyme preparation. It was stored at −20°C.

(iv) Enzyme assay.

FAE activity to the FAA (3.4 mmol liter−1) was determined by HPLC (5). A 1-ml portion of the assay mixture consisting of 30 μl of substrate solution and 100 μl of appropriately diluted enzyme solution in 0.25 mol of morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES)-NaOH buffer (pH 5.6) liter−1 was incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by heating for 3 min in a boiling water bath. The released FA was extracted with 1 ml of ethyl acetate. The extract was then evaporated to dryness with a stream of N2 at room temperature. A total of 40 μl of 50% methanol was added to the dry residues, and the FA content was determined by HPLC (model L-7100; Hitachi) using a Nova-Pak C18 4 μM column (4.6-mm i.d. by 25-cm length; Waters). The column was preequilibrated with 50 mmol of sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) liter−1. A sample (10 μl) was injected and eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 50% acetonitrile in the same buffer for 20 min at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. The FA level was monitored with a UV detector at 320 nm, and the amount of free FA released was quantified from standard curves made in advance. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme which released 1 μmol of FA per min under the conditions described above; specific activity levels are given in units per milligram of protein.

Protein was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method with a commercial protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Bovine serum albumin was used as a standard.

(v) Electrophoresis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed using a 14% polyacrylamide gel in a Mini-Protean II electrophoresis cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the method of Laemmli (24). Protein bands were determined using Silver Stain II kit Wako. The MW values were estimated using MW marker proteins (Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd.) containing monomer (12.4 kDa), dimer (24.8 kDa), trimer (37.2 kDa), tetramer (49.6 kDa), and hexamer (74.4 kDa) of cytochrome c.

Native PAGE was performed using a 6% polyacrylamide gel according to the method of Ornstein and Davis (9, 33).

(vi) MW determination.

MW values were also determined by gel filtration chromatography (GFC) with a column (TSKgel G3000SW; Tosoh) (7.5-mm i.d. by 60-cm length) which had been preequilibrated with 50 mmol of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) liter−1 containing 0.5 mol of NaCl liter−1 and 1 mmol EDTA liter−1. The purified enzyme was eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1.

The column was calibrated before and after the enzyme was subjected to a chromatography procedure using an MW GF-200 kit (Sigma).

(vii) N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of the purified FAE.

The purified FAE was ultrafiltrated (Centricon YM-10; Millipore) (MW cutoff, 10,000) at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C into ultrapure water (Millipore) to get rid of the interference of Tris. The buffer-changed filtrate was treated for N-terminal amino acid sequencing by automated Edman degradation with a PPSQ-21 protein sequencing system (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). N-terminal sequence homology was analyzed using a BLAST database search.

(viii) The degradation of feruloylated sugar esters by the purified FAE.

The degradability of the FAE on FAXN, FAXn, FAXX, and FAA prepared from RCB hydrolysates was determined by measuring the amount of free FA released under the conditions described above. Furthermore, the influence of the presence of xylanase on FAE activity was studied by adding 50 U of xylanase from Trichoderma viride (Sigma)/ml into the assay mixture (final xylanase concentration, 2 U/ml).

(ix) Other analytical techniques.

The optimum pH of the purified enzyme was determined using FAA as a substrate at 37°C. The buffers (at a final concentration of 0.25 mol liter−1) used for the assay were as follows: sodium acetate (pH range, 4.2 to 5.6), potassium phosphate (pH range, 5.0 to 6.0), MES-NaOH (pH range, 5.5 to 7.0), and Tris-HCl (pH range, 6.5 to 8.2). The optimum temperature was determined using FAA as a substrate at pH 5.6 (MES-NaOH buffer). Enzyme thermostability was measured by preincubation of the purified FAE (30 mU) in 0.25 mol of MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.6) liter−1 at various temperatures for different periods of time. The incubation was stopped by cooling on ice, and residual activity was assayed using a standard assay as described above.

The effects of different substrate concentrations on the FAE activity were examined at 37°C in 0.25 mol of MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.6) liter−1 that included the purified enzyme and FAA at various concentrations between 0.017 mmol liter−1 and 0.17 mmol liter−1. Km and Vmax values were obtained by Lineweaver-Burk analysis (25).

The effect of various reagents on the FAE activity was tested. The cations, EDTA, and (±)-DTT were dissolved in 1 ml of 0.25 mol of MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.6) liter−1 that included 100 μl of the purified enzyme and 30 μl of the substrate to give final concentrations of 1 and 5 mmol liter−1. The purified enzyme was incubated for 5 min at 37°C with each of the reagent solutions, and then the residual activity of the enzyme was measured.

RESULTS

Enzyme purification.

The FAE from L. acidophilus was purified (using FAA as a substrate) 147-fold to homogeneity, as summarized in Table 1. For the first HIC, FAE activity was detected in fractions 13 to 16; of these, fractions 14 and 15 [0.73 to 0.67 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1] were found to exhibit the majority (90%) of the FAE activity. After both fractions were pooled and vacuum evaporated, the second HIC procedure was carried out. It was found that fractions 11 to 13 contained the FAE activity and that the majority (99%) of the activity was present in fractions 11 and 12 [0.67 to 0.61 mol of (NH4)2SO4 liter−1]. A combination of fractions 11 and 12 was ultrafiltrated for a buffer change. The FAE activity was confined to fractions 44 to 46; after IEC, the majority of the FAE activity was found in fraction 45 (0.24 mol of NaCl liter−1). Fraction 45 was used for enzyme property studies.

TABLE 1.

Summary of purification of the FAE from L. acidophilus

| Purification | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (mU) | Specific activity (mU mg−1 of protein) | Yield (%) | Purification factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 108.240 | 759.53 | 7.02 | 100 | 1 |

| 80% (NH4)2SO4 | 8.000 | 365.88 | 45.74 | 48.17 | 6.52 |

| HIC (1st) | 1.600 | 147.14 | 91.96 | 19.37 | 13.10 |

| HIC (2nd) | 0.720 | 108.07 | 150.10 | 14.23 | 21.38 |

| IEC | 0.026 | 26.84 | 1,032.31 | 3.53 | 147.05 |

Properties of the enzyme.

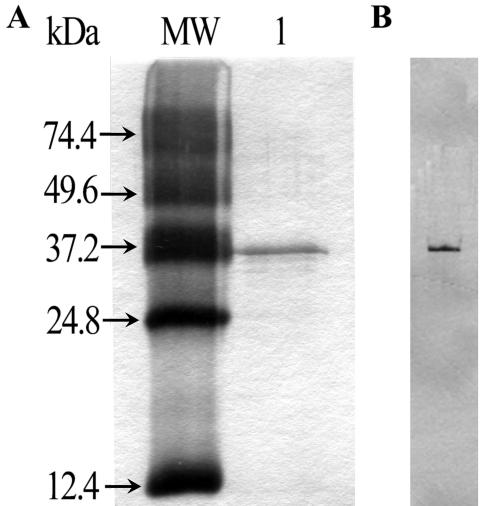

The FAE was confirmed in SDS-PAGE and native PAGE with silver staining as a single band with an estimated molecular mass of 36 kDa (Fig. 1). The molecular mass of the enzyme estimated by using GFC under nondenaturing conditions was 12.4 kDa (results not shown).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE (A) and native PAGE (B) electrophoresis of the purified FAE from L. acidophilus (lane 1). The gel was silver stained.

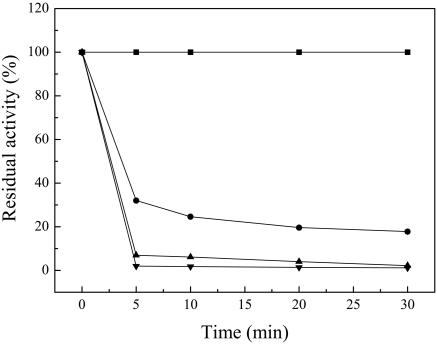

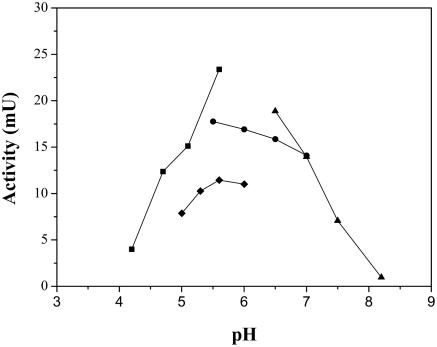

The FAE exhibited maximum activity at 37°C (data not shown). The thermal stability of the FAE was measured in the temperature range of 37 to 75°C. No detectable activity loss was observed after the purified enzyme had been incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After incubation for 5 min at 45 and 65°C, respectively, 68 and 98% of the activity were lost. No activity was detected after incubation at 75°C for 5 min (Fig. 2). FAE had optimum activity at pH 5.6 and showed most activity in the pH range of 5.3 to 6.5 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

The thermostability of the FAE from L. acidophilus for different periods of time at 37°C (▪), 45°C (•), 55°C (▴), and 65°C (▾).

FIG. 3.

Effect of pH on activity of the FAE from L. acidophilus. The enzyme assay was performed at 37°C for 5 min in sodium acetate buffer (▪), MES-NaOH buffer (•), potassium phosphate buffer (♦), and Tris-HCl buffer (▴) (all at a final concentration of 0.25 mol liter−1).

The effect of cations and organic reagents on FAE activity was tested. Among the ions used, Na+ had no effect whereas NH4+, Ca2+, and Mn2+ exhibited a little influence on the enzyme activity. However, Fe3+ and Cu2+ exerted a significantly inhibitory effect. At a concentration of 1 mmol liter−1, Fe3+ and Cu2+ reduced the activity by 93.42 and 92.39%, respectively; at 5 mmol liter−1, the residual activity of the enzyme remained only 5.20 and 2.75%. When FAE was assayed in the presence of the organic reagents, such as EDTA and (±)-DTT, which were used throughout the purification, no significant inhibition was observed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of various reagents on the FAE from L. acidophilus

| Reagents | Residual activity (%) at the indicated reagent concn (mM)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | |

| (NH4)+ | 85.46 ± 4.50 | 65.75 ± 3.85 |

| Ca2+ | 89.95 ± 2.07 | 85.11 ± 2.11 |

| Mn2+ | 83.53 ± 2.02 | 77.08 ± 1.05 |

| Fe3+ | 6.58 ± 1.05 | 5.20 ± 1.70 |

| Cu2+ | 7.61 ± 1.11 | 2.75 ± 0.98 |

| Na+ | 100 ± 1.00 | 100 ± 1.26 |

| EDTA | 75.98 ± 2.64 | 71.37 ± 4.23 |

| (±)-DTT | 72.67 ± 1.08 | 65.39 ± 1.50 |

Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified FAE.

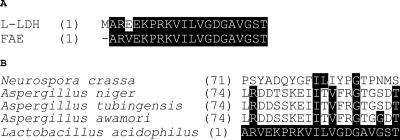

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified FAE was determined as A R V E K P R K V I L V G D G A V G S T. By comparing its N-terminal sequence with those available in the database, we found that the sequence was 95% identical to the N-terminal sequence of l-lactate dehydrogenase (l-LDH) (EC 1.1.1.27) from L. helveticus (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified FAE from L. acidophilus. (A) The search for amino acid sequences homologous to the amino acid sequence of the FAE was performed on BLAST database. The amino acid residues show a high level (95%) of similarity to l-LDH from L. helveticus. (B) Alignment of N-terminal amino acids of the FAE from L. acidophilus with those from A. niger (GenBank accession no. Y09330), A. tubingensis (Y09331), A. awamori (AB032760) and N. crassa (AJ293029) identified to date. Identical amino acid residues among all of the FAEs are shown in white letters on a black background. Numbers in parentheses represent the N-terminal starting positions of the amino acid sequences.

Effect of substrate concentration and degradability on feruloylated sugar esters.

At pH 5.6 and 37°C, the Km and Vmax values for the hydrolysis of the FAA by the FAE were determined as 0.0953 (standard deviation, ±0.0031) mmol liter−1 and 86.27 mmol/liter−1 min−1 mg−1 of protein, respectively.

The ability of the enzyme to release FA with or without the presence of a xylanase was determined using the feruloylated sugar esters as substrates. When only the purified FAE was used, free FA was detected in the medium with FAXX and FAA. However, twofold-more free FA was released from FAXX in the presence of the FAE and added xylanase (Fig. 5B).

DISCUSSION

Although several FAEs from some fungi have been purified and characterized to date, its purification from bacteria has been performed only with Streptomyces olivochromogenes (13). There is no report of a study of the FAE secreted by human intestinal bacteria. Thus, this paper describes the purification and characterization of FAE from a human typical intestinal bacterium L. acidophilus, shows the change in FAE activity induced by the presence of xylanase on the feruloylated sugar esters, and reveals the N-terminal amino acid sequence of FAE from prokaryotic cells for the first time.

The purification procedures consisted of lysozyme treatment, sonication, ammonium sulfate fractionation, and two cycles of HIC and IEC. The results of the purification (in which IEC played a markedly effective role) showed that specific activity increased from 7.02 mU of crude extract mg−1 of protein to 1,032.31 mU of the purified FAE mg−1 of protein.

SDS-PAGE and native PAGE were carried out to examine the purity of the enzyme; these procedures resulted in a single protein band. The apparent molecular mass (36 kDa) of the purified FAE, which was estimated using SDS-PAGE, resembled those of the analogous enzymes from fungus Aspergillus niger (36 kDa) (14), A. awamori (35 kDa) (22), and Clostridium stercorarium (33 kDa) (11) but was higher than that of the analogous enzyme from bacterium S. olivochromogenes (29 kDa) (13). In nondenaturing conditions, the molecular mass of the enzyme was determined by GFC to be 12.4 kDa, which is much lower than that determined by SDS-PAGE. Perhaps the enzyme elution on gel filtration is retarded by its affinity to silica gel particles in a G3000SW column. Similar phenomena have been observed for several other FAEs (11, 13, 14). The optimum temperature and pH were found to be 37°C and 5.6, respectively (precisely indicating the gastrointestinal origin); these results are different from those obtained with most other FAEs, whose optimum temperatures are around 40 to 55°C. Even the purified FAE from prokaryotic (S. olivochromogenes) cells shows a lower temperature (30°C). Moreover, FAE shows a high level of sensitivity to temperature. When the enzymes were incubated at 45°C for 5 min, as much as 68% of the activity was lost. Furthermore, no activity at all was observed after incubation at 75°C for 5 min.

FAE was inhibited markedly by the presence of Fe3+ and Cu2+, a result which was akin to those seen with FAEs from the other organisms. The presence of Ca2+ and Mn2+ suppressed the activity of the FAE from C. stercorarium and that of Ca2+ enhanced the activity of the FAE from Penicillium pinophilum; these phenomena were not observed for the FAE from L. acidophilus.

The Km value recorded for FAA was 0.0953 mmol liter−1, which indicated the high-level affinity of the FAE for the substrate of FAA.

In the present study, the degradability of FAE on the feruloylated sugar esters showed that the smaller the degree of polymerization of plant cell wall polysaccharides was, the more free FA was released by the FAE. No free FA was released by the FAE from the highly polymerized FAXn or FAXN with or without the presence of xylanase from T. viride, whereas in the presence of the xylanase, FA release was enhanced dramatically from the FAXX but not from the FAA. This result demonstrates that xylanase influences FAE activity with respect to the FAXX, probably because xylanase degrades the FAXX into smaller molecules that enable FAE to act. The phenomenon agrees well with many previous studies, in most of which, however, destarched wheat bran was used as substrate; the fragment series of feruloylated sugar esters common in food matrices was first used in the present study. These results are considered to indicate that FAE activity is influenced by both the size and the dimensional structure of sugar moieties linked to ester bonds. They also suggest that the participation of a much more complex enzymatic system is needed to release FA from complex foodstuff in vivo.

So far, there has been no report concerning the primary structure of prokaryotic FAE in spite of the publication of some studies of the gene encoding the FAE from eukaryotic cells (8, 10; GenBank accession no. AB032760). 20 N-terminal amino acids of the purified FAE from L. acidophilus were identified first. A computer search of GenBank revealed a considerable similarity (95%) between amino acid sequences of the FAE from L. acidophilus and the l-LDH from L. helveticus (Fig. 4A). When the LDH activity of the FAE solution from each step during the purification was measured, interestingly, it was found that both crude extract and the solutions from the first and second HIC separations exhibited LDH activity (especially that from the crude extract at a relatively high level). In contrast, purified FAE does not appear to exhibit LDH activity at all (as determined by the method of l-LDH measurement described by Savijoki and Palva [35]; data not shown), which indicates they are quite distinct from each other. We think further study is needed for elucidation of this interesting phenomenon. Furthermore, it was concluded from the results of alignment analysis that the amino acid sequence of the FAE showed a low level of homology with those of the known FAEs from A. niger, A. tubingensis, A. awamori, and Neurospora crassa (Fig. 4B). It was also demonstrated (Fig. 4B) that the level of similarity of amino acid sequences among Aspergillus spp. is fairly high but that the level of similarity between those of N. crassa and Aspergillus spp. is much lower, suggesting that there would be distinctions in the amino acid sequences of FAE due to the differences in microorganism strains.

The FAE from a human typical intestinal bacterium, L. acidophilus, was purified and characterized in this work, which provides an important means for studying the absorption and the metabolism of dietary FA. The enhancement of FAE activity by xylanase has been elucidated as being influenced by the structure of a substrate; this finding enables us to develop more realistic pictures of the mechanism of degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides in the human intestine. With the first report of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of bacterial FAE, we consider this study only one step in the dissection of the interesting FAE system, since it shows fascinating prospects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of The Chiba University Radioisotope Research Center for their provision of equipment and facilities. We appreciate the kind advice from Hirofumi Shinoyama of the Faculty of Horticulture, Chiba University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anasoma, M., K. Takahashi, M. Miyabe, K. Yamamoto, N. Yoshimi, H. Mori, and Y. Kawazoe. 1994. Inhibitory effect of topical application of polymerized ferulic acid, a synthetic lignin, on tumor promotion in mouse skin two-stage tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 15:2069-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen, M. F., A. K. Landlo, L. P. Christensen, A. A. Hansen, and A. S. Meyer. 2001. Antioxidant effects of phenolic rye (Secale cereale L.) extracts, monomeric hydroxycinnamates, and ferulic acid dehydrodimers on human low-density lipoproteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49:4090-4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasen, M. F., P. A. Kroon, G. Williamson, and M. T. Garcia-Conesa. 2001. Esterase activity able to hydrolyze dietary antioxidant hydroxycinnamates is distributed along the intestine of mammals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49:5679-5684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borneman, W. S., L. G. Ljungdahl, R. D. Hartley, and D. E. Akin. 1992. Purification and partial characterization of two feruloyl esterases from the anaerobic fungus Neocallimastix strain MC-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3762-3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne, L. C., and C. A. Rice-Evans. 1999. Detecting and measuring bioavailability of phenolics and flavonoids in humans: pharmacokinetics of urinary excretion of dietary ferulic acid. Methods Enzymol. 299:91-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo, L. 1998. Polyphenols: chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev. 56:317-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castanares, A., S. I. McCrae, and T. M. Wood. 1992. Purification and properties of a feruloyl/p-coumaroyl esterase from the fungus Penicillium pinophilum. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 14:875-884. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crepin, V. F., C. B. Faulds, and I. F. Connerton. 2003. A non-modular type B feruloyl esterase from Neurospora crassa exhibits concentration-dependent substrate inhibition. Biochem. J. 370:417-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, B. J. 1964. Disc electrophoresis-II: method and application to human serum proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 121:404-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVries, R. P., B. Michelsen, C. H. Poulsen, P. A. Kroon, R. H. H. van den Heuvel, C. B. Faulds, G. Williamson, J. P. T. W. van den Hombergh, and J. Visser. 1997. The faeA genes from Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus tubingensis encode ferulic acid esterases involved in degradation of complex cell wall polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4638-4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaghy, J. A., K. Bronnenmeier, P. F. Soto-Kelly, and A. M. McKay. 2000. Purification and characterization of an extracellular feruloyl esterase from the thermophilic anaerobe Clostridium stercorarium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:458-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaghy, J. A., and A. M. McKay. 1997. Purification and characterization of a feruloyl esterase from the fungus Penicillium expansum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:718-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faulds, C. B., and G. Williamson. 1991. The purification and characterization of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic (ferulic) acid esterase from Streptomyces olivochromogenes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2339-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulds, C. B., and G. Williamson. 1994. Purification and characterization of a ferulic acid esterase FAE-III from Aspergillus niger: specificity for phenolic moiety and binding to microcrystalline cellulose. Microbiology 140:779-787. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry, S. C. 1982. Phenolic components of the primary cell wall. Biochem. J. 203:493-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf, E. 1992. Antioxidant potential of ferulic acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 13:435-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, M. T., R. C. Smart, C. Q. Wong, and A. H. Conney. 1988. Inhibitory effect of curcumin, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid on tumor promotion in mouse skin by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 48:5941-5946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato, Y., J. Azuma, and T. Koshijima. 1983. A new feruloylated trisaccharide from bagasse. Chem. Lett. 12:137-140. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato, Y., and D. J. Nevins. 1986. Isolation and identification of O-(5-O-feruloyl-α-L-arabinofuranosyl)-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose as a component of Zea shoot cell walls. Carbohydr. Res. 137:139-150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawabata, K., T. Yamamoto, A. Hara, M. Shimizu, Y. Yamada, K. Matsunaga, T. Tanaka, and H. Mori. 2000. Modifying effects of ferulic acid on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in F344 rats. Cancer Lett. 157:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kikuzaki, H. M. Hisamoto, K. Hirose, K. Akiyama, and H. Taniguchi. 2002. Antioxidant properties of ferulic acid and its related compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50:2161-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koseki, T., S. Furuse, K. Iwano, and H. Matsuzawa. 1998. Purification and characterization of a feruloylesterase from Aspergillus awamori. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:2032-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroon, P. A., C. B. Faulds, P. Ryden, J. A. Robertson, and G. Williamson. 1997. Release of covalently bound ferulic acid from fiber in the human colon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45:661-667. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lineweaver, H., and D. Burk. 1934. The determination of enzyme dissociation constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 56:658-666. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCrae, S. I., K. M. Leith, A. H. Gordon, and T. M. Wood. 1994. Xylan-degrading enzyme system produced by the fungus Aspergillus awamori: isolation and characterization of a feruloyl esterase and a p-coumaroyl esterase. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 16:826-834. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer, A. S., J. L. Donovan, D. A. Pearson, A. L. Waterhouse, and E. N. Frankel. 1998. Fruit hydroxycinnamic acids inhibit human low-density lipoproteins oxidation in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46:1783-1787. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller-Harvey, I., R. D. Hartley, P. J. Harris, and E. H. Curzon. 1986. Linkage of p-coumaroyl and feruloyl groups to cell-wall polysaccharides of barley straw. Carbohydr. Res. 148:71-85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolosi, R. J., L. M. Ausman, and D. M. Hegsted. 1991. Rice bran oil lowers serum total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and apo-B levels in non-human primates. Atherosclerosis 88:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishizawa, C., T. Ohta, Y. Egashira, and H. Sanada. 1998. Ferulic acid esterase activities of typical intestinal bacteria. Food Sci. Technol. Int. (Tokyo) 4:94-97. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohta, T., N. Semboku, A. Kuchii, Y. Egashira, and H. Sanada. 1997. Antioxidant activity of corn bran cell-wall fragments in the LDL oxidation system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45:1644-1648. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohta, T., S. Yamasaki, Y. Egashira, and H. Sanada. 1994. Antioxidative activity of corn bran hemicellulose fragments. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42:653-656. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ornstein, L. 1964. Disc electrophoresis-I: background and theory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 121:321-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rombouts, F. M., and J. F. Thibault. 1986. Feruloylated pectic substances from sugar-beet pulp. Carbohydr. Res. 154:177-187. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savijoki, K., and A. Palva. 1997. Molecular genetic characterization of the l-lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhL) of Lactobacillus helveticus and biochemical characterization of the enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2850-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singleton, V. L., and J. A. Rossi. 1965. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 16:144-158. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slavin, J. L. 2000. Whole grains, refined grains and fortified refined grains: what's the difference? Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 9:s23-s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, M. M., and R. F. Hartley. 1983. Occurrence and nature of ferulic acid substitution of cell-wall polysaccharides in graminaceous plants. Carbohydr. Res. 118:65-85. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Topakas, E., H. Stamatis, P. Biely, D. Kekos, and B. J. Macris. 2003. Purification and characterization of a feruloyl esterase from Fusarium oxysporum catalyzing esterification of phenolic acids in ternary water-organic solvent mixtures. J. Biotechnol. 102:33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wende, G., C. J. Buchanan, and S. C. Fry. 1997. Hydrolysis and fermentation by rat gut microorganisms of 2-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(5-O-feruloyl)-L-arabinose derived from grass cell wall arabinoxylan. J. Sci. Food Agric. 73:296-300. [Google Scholar]