1. Introduction

One of the major structural differences that provides a taxonomic distinction between eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms is that prokaryotes lack the nuclear envelope, with exceptions such as planctomycetes 1, and genomic organization mechanisms found in eukaryotes. Instead, the prokaryotic genome is partitioned into a somewhat amorphous region of the cell known as the nucleoid 2–4. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the genome must be compacted to fit into its allotted space while maintaining a level of organization that allows efficient functionality. In eukaryotes, this is accomplished by well-defined histone proteins that form nucleosomal and chromatin structures and yet can be remodeled to allow for the decondensation critical for gene expression 5–9. Although the bacterial genome must also be densely compacted, more than one-thousand-fold, and also organized for optimum functionality (chromosome replication/segregation, recombination and transcription) 10–14, the mechanisms by which this is accomplished remain unclear. The lack of “beads-on-a-string” morphology indicates different and/or multiple roles for nucleoid-associated proteins. Since transcription is a major cellular function and involves protein-DNA interaction and DNA topological domain structures, the transcription machinery themselves may play a role in nucleoid organization. Conversely, the nucleoid structure and organization may influence gene expression in a manner analogous to chromatin decondensation in eukaryotes. The interactions involved in nucleoid structure and gene expression continue to be challenging issues in the post-genomic era.

Escherichia coli is a preferred model system for prokaryotic research due to the extensive studies into its genetic, physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology mechanisms 15. The study of nucleoid organization is intrinsically difficult mainly due to the small size of bacteria in comparison to the limits of optical resolution of conventional instrumentation. Until very recently, images of the nucleoid have not changed much over the last four decades and reveal no structural details 16–18. Consequently, most of the earlier studies were focused on the biochemical properties and morphologies of isolated nucleoids and electron microscopic images after fixation 3–4,19–24. However, any preparation or fixation procedure will potentially introduce different organizations of the nucleoids or even artifacts. For example, different fixation procedures produced different nucleoid shapes of electron microscopic images 3. Additionally, growing evidence indicates that the organization of the nucleoid in the cell is plastic and sensitive to changes in growth and stress. The challenge of the research is to capture the “true” organization of the nucleoid reflecting the dynamic states of the nucleoid in living cells.

Extensive studies have primarily emphasized the “histone-like” proteins including FIS, HU, H-NS, and IHF for their architectural roles in bending, looping, bridging and compacting DNA 25–36. The first three and RNA polymerase (RNAP) are the major nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) isolated from exponentially growing cells. Compared to the “histone-like” proteins, the binding of RNAP to DNA is much stronger. A prevailing view is that bacterial “histone-like proteins” are primarily responsible for the nucleoid organization and compaction in growing cells.

Recent advances in the cell biology of E. coli RNAP and the nucleoid have shown that the distribution of RNAP, which is coupled to cell growth, plays an important role in the nucleoid dynamic structure. Emerging evidence indicates that formation of the transcription foci centered at the putative nucleolus structure is critical in nucleoid remodeling and influencing global gene expression. As other recent comprehensive reviews have dealt with the roles of other factors in bacterial nucleoid organization 37–43, this review provides an alternative and/or complementary perspective to the traditional views on bacterial nucleoid compaction and expansion.

2. The Nucleoid

The bacterial nucleoid differs from the eukaryotic nucleus in two important ways. The foremost is that the nucleoid lacks a membrane envelope, thus, it interfaces with the cytoplasm intimately. Another is that the mass ratio of protein to DNA of the nucleoid in growing cells appears to be lower than the value of 1:1 for the eukaryotic counterpart 20,44–45. Such low protein density is also revealed by a general smooth appearance of the nucleoid from chromatin spread images 46–47 in contrast to the eukaryotic nucleosomal “beads-on-a-string” morphology 48–50. The reason(s) for the apparent low protein to DNA ratio could be attributed to a low content of proteins in the nucleoid and/or, more likely, to an overall low binding affinity of most of nucleoid-associated proteins compared to histones. These features are critical for bacterial nucleoid structure in the cell.

2.1. Environment

E. coli is a gram negative, rod shaped bacterium which changes size depending on growth conditions. A rigid cell wall maintains osmotic pressure inside the cell and is sandwiched by outer and inner (cytoplasmic) membranes; between the cell wall and the cytoplasmic membrane is the periplasmic space 51. The nucleoid is usually located near the center of the cytoplasm along the long axis of the cell 52 and occupies less than ¼ of the intracellular volume 53. Thus, the interaction between the nucleoid and cytoplasm is extensive at the interface. One example of this interaction is the coupling of transcription and translation 46,54. A special process of such coupling, known as transertion, involves an additional translocation of transmembrane proteins55–58. Although most of the ribosomes are located in areas outside of the nucleoid, recent superresolution imaging reveals that some ribosomes and RNAP are associated with the nucleoid periphery and cell membrane 3,59.

The cytoplasm is filled with proteins, RNAs and ribosomes 60 (Figure 1). Unlike typical biochemical reactions in vitro, which are usually performed at diluted concentrations, the concentration of the macromolecules in the cell is estimated to be 0.3 to 0.5 g/ml 61. This macromolecular crowding is proposed to condense the bacterial nucleoid and influence the interactions between the nucleoid and cytoplasm 62–65. Modeling biological interactions in macromolecular crowding environments have provided many new insights into the forces operating in the cell 66–71. One hypothesis is that genome organization is entropy-driven by depletion attraction 72–73 The E. coli chromosome is also suggested to be a polymer with large-scale coiled organization 74.

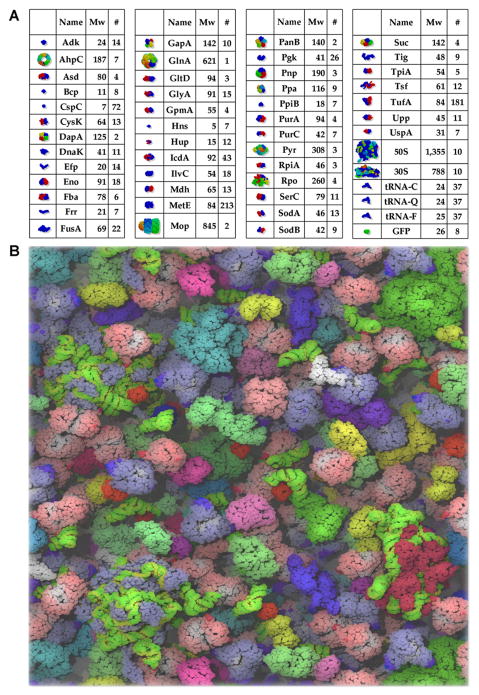

Figure 1.

Macromolecular crowding in E. coli cytoplasm. (A) List of the 50 major proteins found in E. coli cytoplasm (~85% in mass of the total cytoplasm). (B) Modeling of E. coli cytoplasm using the content in (A). Reproduction from McGuffee & Elcock 60.

Recent experiments using a microfluidic device, which allows manipulation and visualization of expansion and condensation of released nucleoids from lysed cells, indicate that the nucleoid behaves as a cross-linked polymer and entropic force (depletion) influences the nucleoid dynamic structure and segregation in the crowded intracellular environment 75.

2.2. Composition

Compact nucleoids isolated from E. coli lysates comprise a folded DNA-RNA-protein complex 20. The complex is approximately 80% DNA by weight; less than 10% is protein and the remaining is RNA and lipids 76–77.

2.2.1. Nucleic Acid

2.2.1.1. Genomic DNA

The E. coli K12 genome is a circular molecule containing ~4.6 million base pairs (bp) 78 and, weighs ~3GDa. When fully extended, it has a contour length of ~1600 μm. The E. coli genome has a single origin (oriC) from which DNA replication 79 proceeds bidirectionally through somewhat stationary “replication factories” 80–83 stopping at the terminus (ter), followed by segregation. The newly synthesized DNA strand is unmethylated and the resulting hemimethylated DNA at each replication fork is bound by SeqA protein 84–85. Sister chromatids are held together (cohesion) for some time during the replication and segregate into two halves of the cells 86–92. The replication-segregation time is ~60 to 90 min in E. coli. Thus there is only one nucleoid in very slow growing cells which have a doubling time > 100 min 93–94.

However, E. coli is capable of very rapid growth, and under optimal growth conditions the doubling time is only ~20 min. When the cell’s doubling time is shorter than the replication-segregation time, there are additional initiation(s) from the oriC before the previous round is completed ensuring that each of the two newly divided daughter cells has at least one completed chromosome 95. Thus, the total DNA content, the number of oriCs connecting sister chromatids and the oriC organization are growth-rate dependent 84,96–97. Multiple oriCs in fast growing cells may be either co-localized 98 or segregated 91,99–100.

2.2.1.2. Nascent RNA

RNA is associated with intact isolated nucleoids and is ~10% by weight. These are nascent RNA molecules attached to elongating RNAP that can “run off” and terminate when NTPs are supplemented 101. About half of the nascent RNAs are rRNA molecules, elongating at the rrn operons in nucleoids isolated from late log phase cells grown in minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% of casamino acids 102. A similar value was obtained from total RNA molecules synthesized in cells under the same growth conditions, demonstrating that the distribution of RNAP in isolated nucleoids is similar to that in living cells.

2.2.2. Nucleoid-Associated Proteins (NAPs)

Primarily four NAPs are identified from nucleoids isolated from lysates of growing cells 20,103. RNAP (core) is the predominant protein, accounting for 50% or more by weight, and the remaining are three small (9 to 16 kDa) positively charged “histone-like” proteins 104–105, including FIS, H-NS and HU. In early log phase cells, FIS, H-NS and HU are the major small NAPs 35,106. However, there are nine other small growth-phase dependent NAPs 33,107 and two unknown proteins 108. Additionally, there are 100–150 transcription factors 109, most of which also bind to DNA influencing transcription by RNAP. Together, these observations suggest that RNAP and transcription play an important role in nucleoid organization.

2.2.2.1. The “Histone-Like” Proteins

FIS (factor for inversion stimulation) 110, H-NS (histone-like nucleoid structuring protein) 111, HU (heat-stable nucleoid protein) 112 and IHF (integration host factor) 113 have been extensively studied biochemically and structurally in vitro primarily owing to their potential “histone-like” functions in nucleoid compaction and they have been studied genetically because they are also transcription factors 114–116 and are involved in recombination 110,117–121. Collectively, they have an architectural role by bending, bridging or wrapping DNA. These properties are important in DNA looping and/or stabilization of supercoiled loops. They also provide mechanisms for regulation of gene expression and recombination by modulating local DNA configurations. As there are several recent reviews on these small NAPs 27,32,34,39,114,122–124, this review highlights other aspects of the “histone-like” proteins relevant to their role in nucleoid organization.

The affinities of the “histone-like” proteins to DNA are significantly weak compared with that of RNAP 28 and histones. Among them, HU has the lowest affinity to DNA while the DNA affinities of FIS, H-NS and IHF are comparable 125. Their relatively weak affinities to DNA, coupled with low coverage of DNA 44, are inconsistent with the notion that the “histone-like” proteins play a major and similar role as histone proteins in eukaryotes 126. This feature instead suggests that the “histone-like” proteins are “on” and “off” the nucleoid dynamically. FIS binding is influenced by DNA breathing dynamics (i.e. local transient DNA “melting” of DNA duplex) 127 based on simulations 128 and by the purine 2-amino group of DNA minor groove 129. In principle, binding of other NAPs could also be regulated by thermal fluctuation of “opening and re-closing” of DNA duplex.

The DNA binding sites for the “histone-like” proteins across the genome have been analyzed by Chip-chip and Chip-seq techniques. These techniques require crosslinking by formaldehyde which only crosslinks stably-bound proteins to DNA 130. Unlike RNAP which is totally crosslinked, ~30 to 50% of H-NS and IHF are not crosslinked to the nucleoids in the cell 131, reflecting their relatively weak affinities to DNA. These properties should be taken into consideration when performing analyses of the genome-wide binding sites for the “histone-like” proteins. For example, these results could explain why HU binding sites are mainly non-specific across the genome 132 as HU has the weakest affinity to DNA among these small NAPs. From these analyses, two features are noticeable. First, H-NS binds to significantly longer tracks of DNA than FIS, suggesting linear H-NS spread along DNA 133. This is consistent with H-NS being a global silencer 116. In addition, H-NS is the only “histone-like” protein that forms “clusters” visualized by superresolution imaging 134. Second, many regions associated with FIS and H-NS are also associated with RNA polymerase 31. The overlapping binding sites for FIS and H-NS are consistent with the reports that these two proteins have antagonizing functions at certain promoters 135–138. The apparent strong association of the binding sites for FIS, H-NS and RNAP in the genome is significant as it indicates that the “histone-like” proteins behave like other transcription factors modulating RNAP binding and/or activity 126,139–140, either positively or negatively.

2.2.2.2. RNA Polymerase (RNAP)

Eukaryotes have three RNA polymerase species in their nucleus, each of which is dedicated to the synthesis of specialized RNA species 141. For example, Pol I is responsible for the synthesis of rRNA at the nucleolus while Pol II performs mRNA synthesis in other parts of the chromosome. Pol III makes small RNAs including tRNAs. In contrast, prokaryotes have only one RNAP responsible for transcription of all RNA species 142–144. E. coli RNAP consists of two forms: core (α2ββ′ ω, ~400KDa) and holoenzyme (α2ββ′ ωσ, ~450KDa) 145. It is a large molecule with dimensions of 17 × 13.5 × 13.5 nm for the holoenzyme 144,146–147 and 8.5 × 10.5 × 14 nm for core RNAP 148. Only the holoenzyme recognizes a promoter and initiates transcription. In general, σ is released shortly after initiation and elongating RNAP (core) stops at the terminators. Transcription factors including NAPs regulate RNAP activities mainly at initiation, but some influence elongation, termination and RNAP recycling 109,149.

Unlike HU, HN-S and IHF, RNAP binds to DNA strongly. The RNAP binding site detected by DNA footprinting varies, ranging from 62–81bp for the initiation complexes 150 to ~23 bp for the elongation complex 151. Most RNAP molecules are likely engaged in synthesizing nascent RNAs in fast growing cells. Single molecule analyses reveal that RNAP is a powerful molecular motor during transcription 152–154. Remarkable transcription processivity is reflected by the fact that elongating RNAP remains tightly associated with the isolated nucleoid even in the presence of 1.0 M NaCl 101.

In addition, both holoenzyme and core RNAP bind to DNA non-specifically with high affinity 155. The fact that the genome contains a vast excess of non-specific DNA suggests that there is minimum unbound RNAP in the cell. Indeed, all RNAP molecules appear to be crosslinked to DNA in the cell in contrast to H-NS and IHF 131. Single molecule analyses show that bound RNAP is able to rapidly slide along DNA for a long distance 156–157 or hop around three-dimensionally 158. Together, such remarkable thermodynamic movements of bound but transcriptionally disengaged RNAP are likely important for searching for promoters and/or maintaining dynamic organizations of transcription machinery.

2.3. Organization

For more than four decades, E. coli nucleoids have been characterized in detail at several levels from isolated nucleoids in vitro to topological domains and other structures in vivo. The vast amount of information accumulated has provided a solid foundation toward understanding the “whole” picture of the nucleoid in living cells. A review of the extensive literature points to the importance of growth conditions, RNAP and transcription, particularly rRNA synthesis in the organization of the nucleoid in the cell.

2.3.1. Isolated Nucleoids

2.3.1.1. Membrane Association

Many methods have been developed to isolate intact nucleoids that maintain their “native” folded compact state 102. A “high-salt” lysis protocol, incorporating 1.0 M NaCl, lysozyme (4 mg/ml) and detergent, is particularly useful for preparation of highly-folded (condensed) nucleoids 20. Both membrane-associated and membrane-free nucleoids have been isolated depending on the temperatures used during lysis 77 and the two forms of the isolated nucleoids confirmed by electron microscopy 159–161. With a “low-salt-spermidine” lysis protocol 103, which contains lysozyme (0.4 or 4 mg/ml), 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM spermidine, only membrane-associated nucleoids are recovered. Several inner membrane proteins of unknown nature are crosslinked to 5-bromodeoxyyuridnine -substituted DNA 162.

However, no specific DNA sequences responsible for the membrane association have been identified 163. The nature of the membrane-DNA interaction is unclear although both replication initiation and chromosome segregation have been suggested to be associated with the membrane 22,164–167. One candidate for membrane-associated proteins is FtsK (~147 kDa), an integral membrane protein and a potent RecA-like dsDNA translocase 168. FtsK is essential for the last steps of chromosome segregation at the dif site of the ter region of chromosome 90,169. Additionally, the transertion process may also contribute to membrane association 170.

2.3.1.2. Effects of Growth Media and Antibiotics

Isolated nucleoids are characterized using sucrose gradients. The nucleoids isolated from nutrient-rich medium have a sedimentation coefficient of 3200 S 20, whereas those isolated from minimal medium have an estimated value of 1700 S 21. In addition, the nucleoids isolated from lysates of amino-acid starved cells have a further reduced sedimentation coefficient of 1300 S compared with those from the unstarved cells (1700 S). Although the reduced S value could be due to a reduced DNA content, it is also possible that the nucleoids in cells grown in minimal medium and in amino-acid starved cells are decondensed.

Nucleoids isolated from cells treated with different antibiotics also exhibit different relative sedimentation velocities compared to those of untreated cells 76. For example, inhibition of transcription by rifampicin reduces the relative sedimentation coefficient more than 10-fold. Addition of rifampicin to the condensed nucleoids in vitro causes no such change, indicating that inhibition of transcription in vivo is critical for reduction of sedimentation 77. In contrast, inhibition of translation by chloramphenicol increases the relative sedimentation coefficient two-fold, suggesting condensation of the nucleoids. Inhibition of supercoiling by the gyrase inhibitor nalidixic acid has no effect on the relative sedimentation velocities 76.

2.3.1.3. Supercoiled loops

The condensed nucleoids are negatively supercoiled and the number of the supercoiled loops varies dependent on the method used. An estimate of 12 to 80 loops is suggested by changes in the relative sedimentation coefficient after ethidium bromide intercalation and DNA single-strand nicking with DNase 21. Each supercoiled loop is an independent domain; eliminating one loop has no effect on the others. However, extensive nicking results in an unfolded nucleoid without supercoiled loops. Electron microscopy measurements of membrane-free nucleoids indicate 98 to 194 supercoiled loops of variable sizes in a rosettes-like morphology for every chromosome 160. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that supercoiling compacts the nucleoid. More recent studies indicate that there are about 500 supercoiled loops in growing cells 171–172 (see below).

2.3.1.4. RNA Core

RNase treatment converts a condensed nucleoid into a decondensed structure 77, and it was proposed that RNA binds to DNA and defines the barriers separating the supercoiled loops. Electron microscopy of membrane-free folded nucleoids shows that they seem to have a central core consisting mostly RNA surrounded by ordered DNA fibers and supercoiled loops 160. RNase treatment of the nucleoid also appears to alter the nucleoid structure by atomic force microscopy analysis 173. However, the RNA molecules responsible for the nucleoid compaction have not been identified. Additional in vivo experiments have as yet found no role of nascent RNA in stabilization of supercoiled domains 174. Thus, the implied role of RNA in nucleoid compaction is likely an artifact introduced during the procedures for nucleoid isolation (see below).

2.3.1.5. Lysozyme effect

Nucleoids released from E. coli spheroplasts after low osmolarity shock in the presence of very low concentration of lysozyme (3μg/ml) appear as cloud-like structures; however, a relatively high concentration of lysozyme (30 μg/ml) condenses the nucleoid significantly, reducing the volume by 3-fold 175. Lysozyme is a strongly positive charged molecule with an isoelectric point (pI) of 11.16 176. Thus, lysozyme could compact the nucleoids by interactions with DNA loops and/or nascent RNA. Note that all the protocols mentioned above use high levels of lysozyme and, indeed, the isolated nucleoids from those protocols contain significant amounts of lysozyme 125. However, RNase treatments have no effect on the structure of the nucleoids isolated in the presence of a very low level of lysozyme. Apparently, organization of isolated nucleoids is influenced greatly by the conditions used during preparation.

2.3.2. Topological Domain Structures in vivo

2.3.2.1. Supercoiled domains

The negative supercoiling of the E. coli chromosome is maintained by topoisomerases 177–179 and other factors 180. DNA gyrase is a critical factor because it introduces negative supercoiling 181. RNAP is also important because transcription and supercoiling are coupled 182. Particularly, elongating RNAP generates positive supercoils ahead and negative supercoils behind 183. The twin domain introduced by RNAP suggests that DNA topoisomerases are actively involved in the elongation step of transcription 184. Gyrase appears to be co-localized with highly expressed genes 185, reflecting the need for gyrase action ahead of the active elongating RNAP at those genes.

The state of supercoiling of the E. coli chromosome is thus likely to be strongly influenced by transcription locally and globally. The extremely high expression of ribosomal RNA operons (rrn) in fast growing cells is proposed to generate extraordinary high density of negative supercoiling near those regions 186. It is also suggested that supercoil densities in fast growing cells are higher than those in slow growing cells 187. Changes in supercoiling are associated with transitions in growth phases and the antibiotic rifampicin, which inhibits transcription initiation, causes DNA relaxation 188. Small NAPs could modulate supercoiling by either affecting the expression of gyrase and topoisomerase I 173 or regulation of global transcription 189–192.

The diffusion of supercoiling generated from distant transcription can be followed by monitoring the expression of supercoiling-sensitive promoters. The leu-500 promoter is activated by negative supercoiling 193 and without nearby transcription activity is not functional 194; however, it can be activated if there is remote transcription spreading negative supercoiling 195. Thus, supercoiling diffusion has the potential to modulate the expression of other genes within a supercoiled domain.

Transcription-induced supercoiling barriers are demonstrated by inhibiting recombination in vivo 196–197. Moreover, higher transcription activities introduce stronger barriers 198 and R-loops 199. Results obtained by probing the spread of relaxation from double strand DNA breaks near supercoiling sensitive genes in vivo have let to the suggestion that the supercoiled domains are flexible both in size and position in the chromosome, and that there are about 500 supercoiled loops having an average size of ~10 kb 171. A similar predominantly stochastic supercoiled domain structure has also been reported in Salmonella 172. Supercoils can be stabilized by coupled transcription and translation 200. In addition, DNA binding proteins can confine DNA supercoils to localized regions 201. It seems likely that other NAPs and transcription factors could act as barriers or insulators of supercoiled domains 202.

2.3.2.2. Macrodomains

Using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique with probes covering different regions of the E. coli chromosome, two major domains have been identified 203. One is the Ori domain which encompasses a large region of the genome including oriC, and the other is the Ter domain which includes a large segment of the genome around the dif of the terminus region. These two domains tend to be positioned at different locations in the cell during the cell cycle. Subsequently, using the lambda att sites-mediated recombination system 204, long-range DNA interactions of the att sites located at different positions of the chromosome have been determined; based on the frequencies of the recombination events, the macrodomain organization of the E. coli chromosome was proposed 205. In this model, the nucleoid is organized into four major domains, including the Ori, Ter, Right and Left and two other minor less-structured regions.

Many processes and factors, such as replication and transcription machineries, influence the formation of macrodomains. One of these factors, MukB (~170 kDa), is implicated in the macrodomain organization because the Ori and Ter domains are abnormally positioned in a mukB mutant 206. MukB is a member of the SMC (structural maintenance of chromosome) protein family 207. MukB consists of an N-terminal ATP/GTP binding domain, two long segments of coiled-coil separated by a hinge and a C-terminal DNA binding 208. The structure of MukB shows two thin rods with globular heads at the ends with a flexible center hinge in an “open” or “closed” configuration 209.

The mukB mutation results in accumulation of anucleated cells and cells with expanded nucleoids 203,210. Mutations in the topoisomerase I encoding gene, topA, suppress the segregation defect of the mukB mutant, indicating that suppression is due to an increase of negative supercoiling 211. The mukB chromosome exhibits reduced negative supercoiling compared to wild type, whereas, another cell cycle mutation, seqA, has increased supercoiling 212. In contrast to MukB, SeqA appears to decrease the supercoiling in the cell 213. How MukB and SeqA modulate supercoiling and affect DNA condensation during the cell cycles at different growth conditions remains to be determined. Other macrodomain associated proteins, such as SlmA and MatP, have been described 214.

2.3.3. Hyper-condensed Structures during Extreme Physiology

2.3.3.1. In Late-Stationary-Phase Starved Cells

Global expression pattern changes accompany growth transitions 215. In particular, Dps (19 kDa), a DNA-binding protein that protects DNA against multiple stresses during the stationary phase 216–217, accumulates rapidly during the stationary phase and is one of the few proteins still being expressed in late stationary phase when cells are starved 218. Intriguingly, DNA-Dps complexes are extremely stable in vitro and have similar crystalline structures both in vitro and in 2-day cultured cells in which Dps is overproduced 219. Formation of DNA-Dps crystalline structures may have evolved to isolate damaging agents from the genome. Similarly, RecA-DNA coaggregates reveal lateral assembly morphology in SOS-induced cells 220. The link between stress and highly ordered nucleoid structures has been discussed elsewhere 221.

2.3.3.2. High Salt Shock during Initial Osmotic Stress Response

Osmotic response is essential for cell survival in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes 222. It induces sequential changes in physiology and gene expression in E. coli 223–226. The effects of high salt shock on the nucleoid structure and RNAP distribution in vivo are visualized in time-course experiments 131. Shortly (< 20 min) after the hyper-osmotic stress response was induced by the addition of 0.5 M NaCl into fast growing cells (LB, 37°C), the nucleoid became hyper-condensed when cytoplasmic K+ accumulated transiently (Figure 2). During a subsequent osmoadaptation phase when K+ levels decreased accompanying accumulations of organic osmoprotectants, the nucleoid gradually de-condensed approaching the pre-stress state. In parallel, RNAP dissociated from the nucleoid during the initial high shock followed by re-association during the adaptation, demonstrating that the interaction between RNAP and DNA is governed by the same thermodynamic principle in vivo as it is in vitro155,227–228. It is speculated that shortly after salt shock the transient dissociation of RNAP from the genome with concurrent nucleoid condensation could be an effective way to silence genome-wide gene expression. During the early adaptation phase, active expression of osmotic stress response genes presumably occurs at the surface of the hyper-condense nucleoid 131.

Figure 2.

The nucleoid is hyper-condensed shortly after high salt shock. Nucleoid and nucleoid/cell overlay of E. coli cells before (LB), 20 min and 45 min after induction of an osmotic shock by 0.5M NaCl. The nucleoid initially becomes hyper-condensed and then gradually re-expanded to a pre-stress state. The nucleoid is stained with Hoescht 33342. The scale bar represents 2 μm. Adapted from Cagliero & Jin 131.

3. Dynamic Nucleoid Organization by RNAP

Many processes and/or factors influence dynamic nucleoid organization. The contribution of chromosome replication and segregation to nucleoid organization during a single cell cycle in very slow growing cells is well recognized 12–13,88–89,229–231. In rapidly growing cells, the replication also play a critical role in nucleoid organization through SeqA-mediated interactions and such interactions could promote cohesion of the newly synthesized chromatin 232. Topological domain structures are important for DNA condensation and the formation of macrodomains. The architectural roles of “histone-like” NAPs have been extensively studied; their implications in nucleoid compaction are almost exclusively extrapolated from in vitro analyses. Growing evidence indicates that their primary function in vivo is transcription regulation 126,139–140,233.

The intertwined relationship between transcription and supercoiling suggests a critical role for RNAP in modulating the dynamic nucleoid structure in response to changes in nutrient status and growth conditions. Co-imaging of RNAP and the nucleoid provides new insights on the role of RNAP in the organization of the E. coli nucleoid as the quality of images improves. By studying the distribution of RNAP under different growth conditions, evidence has emerged that the dynamic genome-wide distribution of RNAP, which is predominantly determined by the status of rRNA synthesis, influences the nucleoid compaction/expansion in the cell 14,234–235.

3.1. Imaging RNAP Distribution in the Cell using RNAP-Fluorophore Fusion

E. coli strains containing derivatives of rpoC-gfp fusion in its normal location in the chromosome of the prototype K-12 strain MG1655 have been constructed to study the cell biology of RNAP by fluorescence microscopy 234–237. The distribution of RNAP is dynamic and sensitive to environmental cues 234. The strains containing the rpoC-gfp fusion are temperature sensitive for growth at > 30°C likely owing to the GFP protein folding problem. Unlike with most of GFP-fusion proteins, the true states of RNAP and the nucleoid are affected due to perturbations in growth and physiology, when cells are sampled from a rapidly shaking flask and agarose embedded on coverslips. To overcome the complications owing to rapid bacterial adaptation, a procedure was developed in which cells are rapidly fixed with formaldehyde to “freeze” RNAP and subcellular structures before imaging, yielding reproducible results that are consistent with the genetics and physiology of E. coli cells. Microfluidic technology will be useful for live-cell imaging of RNAP and nucleoid to examine whether results from fixed-cells represent the distribution of RNAP and structure of nucleoid found in living cells.

With a new generation of fluorescent protein Venus 238, E. coli strains with the rpoC-venus fusion exhibits wild type growth phenotype and growth rate at different temperatures and media 131; thus, experiments can be performed at optimal conditions at 37°C in LB. Compared to the RNAP-GFP protein, the RNAP-Venus protein is brighter, thus significantly enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio. Coupled with a more sensitive imaging system, new detailed structure and texture information for both RNAP and the genomic DNA are revealed (in sharp contrast, previous studies with the rpoC-gfp fusion showed that the nucleoid has blob morphology with no structural and textural details). As described below with the new images of the strains containing the rpoC-gfp fusion, these improvements have significantly advanced our study allowing some detailed analysis of the intensities of RNAP and the DNA in images for further understanding the role of RNAP in the organization of the nucleoid during growth and stress.

Recently, superresolution imaging of RNAP using β′-yGFP 59 and photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) imaging of RNAP are reported 239. These new superresolution techniques provide new details on the distribution of RNAP in the cell.

3.2. Nucleoid Structures and Growth Conditions

As shown in figure 3, the sizes of E. coli cells vary significantly under different growth media. Fast growing cells in optimal growth conditions (LB 37°C, doubling time (DT) 20 min) are the largest with dimensions of 0.7–1.7 μm (short axis) × 3.5–10.7 μm (long axis), while slow growing cells (minimal MOPS with poor carbon source glycerol) are the smallest (among growing cells) with dimensions of 0.5–1.2 μm (short axis) x 2.0–3.3 μm (long axis). Temperature also affects the growth rates and, in the same medium, cells grow slower at 30°C than at 37°C. However, stationary phase cells from LB overnight cultures are much smaller (0.7–1.1 × 1.0–2.1μm) than those of mid-log cultures. Regulation of cell size in response to fatty acid availability has been reported 240. Note that the growth rate of E. coli in the intestine of mice can reach the same fast growth rate during optimal laboratory growth condition with LB and vary with similar ranges in animals as in the test tubes 241. Thus the growth rate regulation by nutrient status likely reflects E. coli physiology in the hosts.

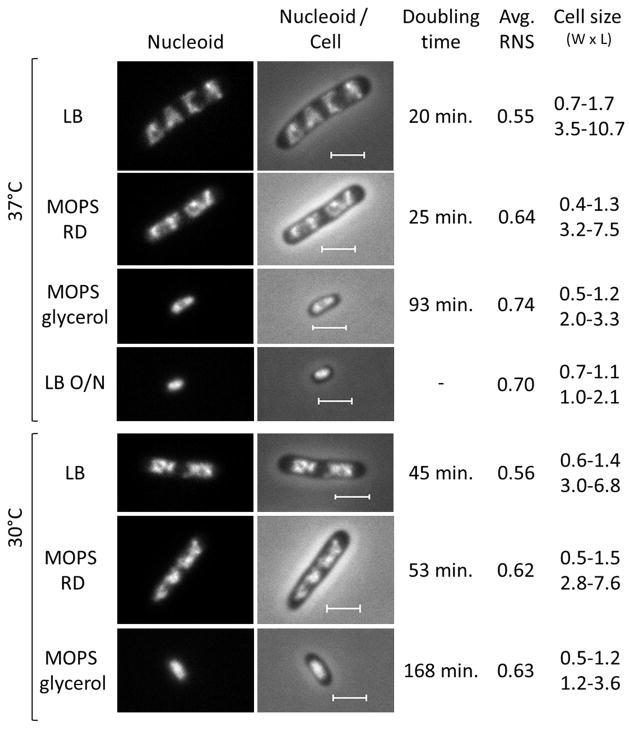

Figure 3.

Cell size and nucleoid structure are sensitive to growth rate and media. Nucleoid and nucleoid/cell overlay of exponential phase cells (rpoC-venus) growing in different media (LB, MOPS rich defined (RD), MOPS glycerol) at different temperatures (37°C or 30°C) or in stationary phase cells growing in LB at 37°C overnight (LB, O/N). The nucleoid is stained with Hoescht 33342. Cell size represents the range of cell width (W) and cell length (L) in a population of unsynchronized cells. The scale bar represents 2μm.

The relative nucleoid compaction in the cell can be measured empirically as the relative nucleoid size (RNS), which is the ratio of the nucleoid(s) length to that of the cell 235,242. In fast growing cells (LB, 37°C) the four apparent nascent nucleoids are relatively compact as indicated by the ample cytoplasmic space and a smaller relative nucleoid size (RNS) value (0.55). Additionally, the nucleoids reveal structural details with textural variations and apparent voids. In rich defined-minimal medium (MOPS+RD), there are only two well separated nascent nucleoids, each of which has two undefined nascent nucleoids; the RNS value (0.64) is significantly higher than that of LB cells. The single nucleoid in the slowest growing cells is expanded with a RNS value (0.74) and there is little texture variation in the nucleoid. In the stationary phase cells which are the smallest, the smooth nucleoid has an average RNS value of 0.7 within a cell not much bigger than the nucleoid.

Media apparently have far more influence on nucleoid compaction than growth rate per se. For example, nucleoids are significantly more compact (RNS = 0.56) in cells grown in LB at 30°C with a doubling time of 45 min compared with those (RNS = 0.64) in cells grown in MOPS-RD at 37°C with a doubling time of 25 min. It is probable that there are some undefined nutrients in LB which are missing in the rich defined (RD) MOPS medium.

3.3. Dominant Transcription Foci for Active rRNA Synthesis

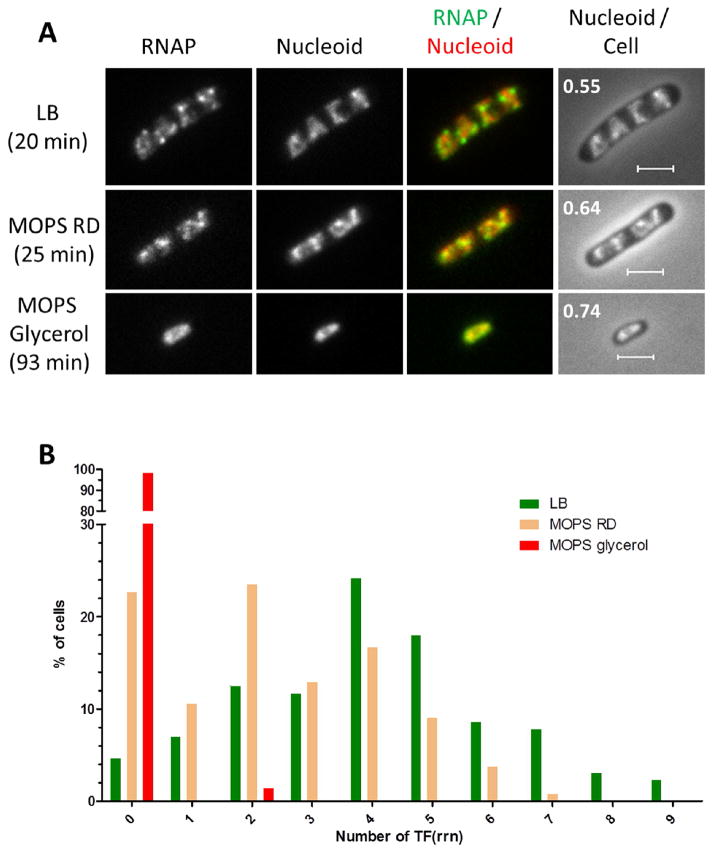

During rapid growth in LB, the majority of RNAP molecules is concentrated at transcription foci 131,234 (Figure 4). These dominant foci presumably locate at the putative nucleolus structure for active rRNA synthesis; thus they are named TF(rrn). Recent PALM imaging of RNAP in rapidly growing cells shows large clusters of >500 RNAP that are likely engaging in rRNA synthesis from multiple rrn operons 239. In addition small clusters of 70 RNAP that are attributed to the transcription of a single rrn operon are also revealed. Formation of transcription foci is sensitive to growth media as the transcription foci diminish in rich defined-minimal medium (MOPS + RD, DT 25 min) and there are no apparent foci in very slow growing cells in minimal medium with poor carbon source (MOPS + glycerol, DT 93 min). The lack of transcription foci is consistent with the low transcription of rrn from cells grown in nutrient-poor media 243.

Figure 4.

Growth-rate dependence of transcription foci in the rpoC-venus cells grown at 37°C. (A) RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP/nucleoid overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay (RNS value is indicated) of cells grown in different media (LB, MOPS rich defined (RD) and MOPS glycerol; the growth rates are indicated). In the RNAP/nucleoid overlay, the RNAP is false colored in green and the nucleoid is false colored in red. The scale bar represents 2 μm. (B) The number of transcription foci per cell in a population (about 100 cells) of asynchronous cells grown in different media. The number of transcription foci decreases as the nucleoid expands and the available nutrients in the media decrease leading to reduced growth rates.

Evidently, both the nucleoid structure and the formation of transcription foci are sensitive to growth media; further, the RNS value, which is an index for nucleoid compaction/expansion, is inversely correlated to the richness of the growth media. To recognize the role of RNAP in the organization of nucleoid it is essential to understand growth rate regulation including the stringent response and its effect on the distribution of RNAP in the cell.

3.4. Growth Rate Regulation and rRNA Synthesis

A landmark in bacterial physiology is the finding more than 50 years ago that bacterial growth rate as measured by cell mass and RNA level is regulated in response to growth media 244–245. Subsequently, it was determined that growth rate is a function of the rate of rRNA synthesis (including tRNA), from which ribosomes are assembled to meet the demand for protein synthesis 243,246–248. Since then, regulation of rRNA synthesis has been extensively studied 249–251. The effect of the differential distribution of RNAP between rRNA and mRNA genes on growth rate regulation has been reviewed elsewhere 186.

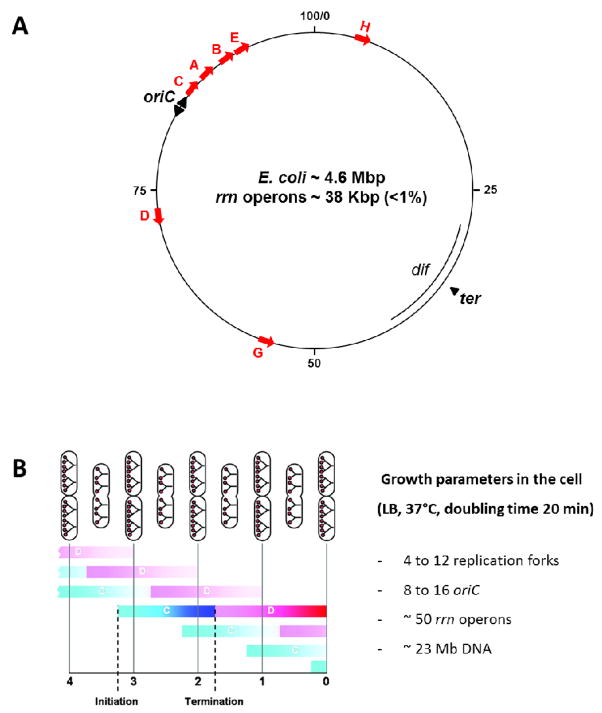

There are seven rrn operons in E. coli and their positions in the E. coli map are shown in figure 5A. The direction of transcription of the seven rrn operons is the same as that of replication. This co-directionality likely evolved to avoid replication–transcription conflicts in bacteria 252, as transcription of rrn is extremely active in fast growing cells. In addition, 93% of ribosomal protein genes and about 66% of the essential genes are transcribed in the same direction as that for rrn 253–255. Having multiple rrn operons is likely advantageous for the cells to rapidly respond to changing environmental conditions 256–257.

Figure 5.

(A) Position of the rrn operons, oriC and ter regions in the E. coli chromosome map. The red arrows represent each of the seven rrn operons, all of which are localized in the oriC proximal half of the chromosome and four of them are near the oriC. Transcription of rrn occurs in the same direction as replication. Adapted with modification from Jin et al.186. (B) Typical cell cycle of E. coli growing in rich media (LB). The red dots represent the multiple copies of oriC in the cell. The C period (period of replication) or the D period (termination and post replication period) is also represented. Multiple rounds of replication initiation increase the gene dosage of oriC (8 to 16 ori) and the number of nascent nucleoids (4 nucleoids). Adapted from Nielsen et al. 100. The calculated numbers of replication forks, oriC and rrn as well as the DNA content of the genomes in a fast growing cell with a doubling time of 20 min are listed.

The seven rrn operons encompass less than 1% of the genome; however, the status of rRNA synthesis in response to changes in growth conditions has the most profound effect on the distribution of RNAP in the nucleoid. Three features of rrn contribute to the unique role of rRNA synthesis in driving the distribution of RNAP. First, all seven rrn operons are located in the origin half of the chromosome and, particularly, four of them are clustered near oriC. Their proximity to oriC makes the copy number (or gene dosage) of rrn especially sensitive to growth rate regulation.

The copy numbers of rrn genes and genome equivalents can be calculated on average per cell based on the growth rate of the cell 243,258. In fast growing cells during optimal growth conditions (LB, 37°C, doubling time 20 min), it is calculated that there are ~50 copies of rrn, of which ~33 copies of rrn are located near the multiple oriC loci (8–16 copies), and five genome-equivalents (23Mb) per cell. Before cell division, each cell has four nascent nucleoids; each nucleoid could have up to four copies of oriC (Figure 5B). Thus, mature cells have up to 16 copies of oriC, whereas newly divided daughter cells have up to eight copies of oriC 100.

Two additional features are related to the length of the rrn transcripts and their regulation. The seven rrn operons have essentially the same organization and regulation 259. The coding sequence for the rrn operons is long; the ~5.5 kb rrn transcript is processed to mature rRNA including 16S, 23S and 5S and tRNAs 260. Regulation of rRNA synthesis is mainly at the initiation 250,261, although it is also regulated to a lesser extent by elongation and the antitermination system 262–264. There are two very strong promoters for each rrn 265, of which P1 is the major promoter responsible for growth rate regulation 266. The P1 promoter has extensive regulatory elements including a G/C rich “discriminator sequence” 267 and binding sites for small NAPs including Fis, H-NS and Lrp (leucine-responsive protein) 268–270. In nutrient-rich media, P1 is the strongest promoter in the cell approaching one initiation per second 271 and rRNA synthesis comprises the most active transcription activity in the cell 243. Multiple factors contribute to the superior strength of the P1 promoter including the “UP” element 264,272 and multiple Fis binding sites that recruit and stabilize the initiation complex 268,273. However, in nutrient-poor media the P1 promoter activity decreases significantly 264,274–275, and during nutrient starvation the P1 activity is minimal 276.

3.5. Stringent Response vs. Growth Rate Regulation

When cells are starved for amino acids, rRNA synthesis ceases almost immediately, accompanied by a rapid accumulation of the alarmones, pppGpp and ppGpp, collectively called (p)ppGpp 277. This starvation-induced response is named the stringent response 278. (p)ppGpp is synthesized by both RelA and SpoT 279; however, RelA is mainly responsible for its production during amino acid starvation. Thus, in contrast to wild type having a “stringent” phenotype, the relA mutant cells exhibit a “relaxed” phenotype as rRNA synthesis remains active during the amino acid starvation 280–281.

The alarmone (p)ppGpp binds to RNAP 282–284 and inhibits initiation from the P1 promoter by destabilization of the initiation complex 285. The DksA protein potentiates the regulation of P1 by (p)ppGpp 286. In addition, (p)ppGpp could affect rRNA synthesis by enhancing the pausing of elongating RNAP on rrn 287. Thus, rRNA synthesis is negatively controlled by (p)ppGpp and P1 is a stringent promoter.

In addition to rrn, there are a few other genes with promoters that are regulated similarly to rrn P1 both in vivo and in vitro; thus they are classified as genes that are regulated by stringent promoters 288. Significantly, these promoters are extremely sensitive to negative supercoiling; the initiation complexes are stabilized by supercoiled DNA but RNAP dissociates rapidly from relaxed DNA 288. Active transcription from these strong promoters will likely generate “waves” of negative supercoiling behind towards the promoters in fast growing cells, whilst inhibition of transcription will abolish supercoiling during starvation, constituting a supercoiling feedback regulation 186. This class of genes includes those involved in the translational machinery (tRNA and tRNA processing enzymes) 289–293, synthesis of nucleotides 294, cell motility machinery 276,295, and replication and transcription machinery 296. The rrn operons and these “rrn-like” genes are regulated similarly (for simplicity hereafter they are represented by rrn) which are distinguished from the vast majority of the “non-rrn” genes in the genome.

Because both bacterial growth rate and rRNA synthesis are inversely correlated to the concentration of (p)ppGpp, ranging over 100-fold from basal level to maximum level during the stringent response 297–299, growth rate regulation and the stringent response are clearly interrelated. At one end of the spectrum during optimal growth in nutrient-rich media, P1 has maximum strength, while at the other end of spectrum during nutrient starvation the promoter has minimum strength owing to the intrinsic instability of the initiation complexes 261. The growth rate regulation of rrn is thus likely a continuum depending on nutrient availability in the media.

Studies of a special class of RifR RNAP mutants have suggested that the dual aspects of the stringent response are mechanistically related. These RNAP mutants are named “stringent” mutants because they exhibit constitutive stringent phenotypes affecting the dual aspects, i.e. decreasing rRNA synthesis even in nutrient-rich LB and activation of amino acid biosynthetic operons in the absence of (p)ppGpp 300. Biochemical characterizations of these “stringent” mutant RNAPs have shown that the initiation complexes of rrn P1 and several other stringent promoters with these mutant RNAPs are extremely unstable and prone to dissociation compared to wild type RNAP 288, thus providing an apparent link between dissociation of RNAP from rrn P1 and more available RNAP for transcription of other non-rrn genes in the genome.

Based on the characterizations of these stringent RNAP mutants both in vivo and in vitro, it is hypothesized that the redistribution of RNAP between rrn and “non-rrn” genes is a key mechanism for the stringent response in the cell. Specifically, during rapid growth, most RNAP molecules are used up by active rRNA synthesis (and other stringent genes), thus RNAP is limiting for transcription of other “non-rrn” genes such as amino acids biosynthetic operons. In contrast, during a starvation stress that induces the stringent response, RNAP molecules released from the rRNA synthesis become available and can be directed by transcription factors for transcription of non-rrn genes, such as amino acids biosynthetic operons. Between the two ends of the spectrum is the continuum of growth rate regulation. This model predicts that the distribution of RNAP is skewed (or biased) to rRNA synthesis on 1% of the genome at the expense of global genome-wide transcription in fast growing cells; conversely, RNAP redistribution enables “balanced” transcription across the genome in nutrient-poor and starved cells.

Transcription profiling from wild type and the “relaxed” relA mutant cells before and after amino acid starvation has been analyzed 276,301–302. An important finding from these studies is that, compared to non-starved cells, the number of genes with increased expression (or activation) is about 3-fold higher than that of genes with reduced expression during starvation in wild type cells. Similarly, an apparent inverse correlation between the number of genes which are activated and rRNA synthesis is also observed during carbon sources starvation 303. Amino acids biosynthetic operons are typical examples of the genes which are positively controlled (or activated) by (p)ppGpp during the stringent response, as (p)ppGpp-less double relA spoT null mutant cells are defective in growth on minimal media without supplementation of amino acids 279. Promoters for amino acid biosynthetic operons are stimulated by (p)ppGpp 304 and further potentiated by DksA 305. Thus, decreasing rRNA synthesis is linked to activating genome-wide transcription, consistent with the RNAP redistribution model during the stringent response. The principle is likely to be true in cells with other stresses.

3.6. RNAP Distribution dictated by rRNA Synthesis

3.6.1. Imaging RNAP Distribution by Chromatin Spreading

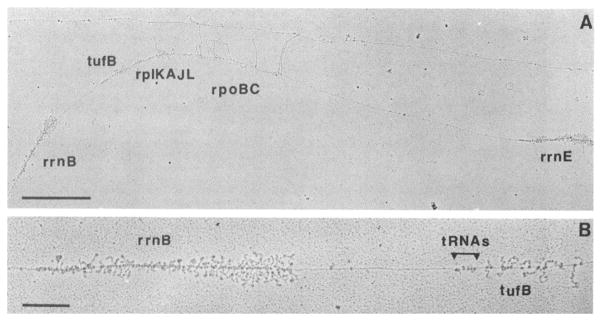

The distribution of RNAP in the nucleoids has been examined by chromatin spreading from E. coli cells grown in different media. The distinctive double Christmas tree morphology is the signature of active rRNA synthesis on rrn and is easily identified on an electron micrograph from fast growing cells 46. This unique morphology is the consequence of nascent pre-rRNA cleavage by RNase III resulting in two gradients of increasing length of 16S and 23S rRNA transcripts 306–307. As expected, the double Christmas tree morphology is absent in the chromatin spread from slow growing cells 308–309 because rRNA synthesis is minimal in nutrient-poor media. This is also consistent with the lack of transcription foci in slow growing cells with the MOPS+glycerol medium mentioned above.

Figure 6 illustrates a skewed genome-wide distribution of RNAP in fast growing cells with LB 47. The high density of nascent rRNA transcripts makes the two rrn operons (rrnB and rrnE), which are separated ~ 40kb, the most easily identified in the electron micrographs. Each of the rrn operons has almost the same densities of rrn transcripts; RNAP is densely packed having one RNAP every 85 bp with little space between them. Thus, there are 65 RNAP per rrn operon on average. A higher number of ~ 70 RNAP per rrn operon (or one RNAP per 79 bp) has also been reported 258,271. In contrast, RNAP densities transcribing other genes are significantly reduced, ranging from one RNAP per1 kb in the rpoBC genes to unidentified lone transcripts with one RNAP separated by 10 to 20 kb.

Figure 6.

Chromatin spread of rrnB-rrnE region from cells grown in LB. (A) Large view of the rrnB-rrnE region. The rrnB and rrnE operons are easily distinguished due to their heavy transcription. The other highly transcribed genes (tufB, rplKAJL, rpoBC) contain on average only 1 RNAP per Kb. The effect of the transcription attenuator between the rplKAJL operon and rpoBC operon is visible by a drop in the number of RNAP. The rest of the DNA (between rpoBC and rrnE) contains much less RNAP with only one per 10 to 20 Kb. (B) Higher magnification of the rrnB operon and tufB gene. The double Christmas tree is visible. There is on average one RNAP per 70 bp in each rrn operon. Reproduction with permission from French & Miller 47.

Significantly, the chromosome is mostly transcriptionally inactive and there are regions as long as 30 to 40 kb totally devoid of transcript and RNAP in the chromatin spread images from cells grown in nutrient-rich LB. Larger regions of nucleoid thus appear to be “naked” with a smooth appearance morphology and no other bound NAPs are apparent. These data support the results that (i) E. coli nucleoid has a low mass ratio of tightly-bound protein and DNA and (ii) RNAP is the predominant and stably-bound NAP in contrast to the “histone-like” proteins and other NAPs.

The chromatin spread images are also consistent with the results that nascent rRNA molecules are the predominant RNA species in the isolated nucleoids from cells grown in a nutrient-rich medium 101–102. However, these analyses have provided no information on whether RNAP engaging in active rRNA synthesis is concentrated together with multiple rrn operons or separated with each individual rrn operon in the nucleoids of rapidly growing cells. Nor do they suggest any role of RNAP associated with rRNA synthesis in the organization of the nucleoid in the cell. However, as described below, microscopy images with RNAP-Fluorophore Fusion and with nucleoid (DNA) from co-imaging suggest that rRNA synthesis is concentrated in the transcription foci consisting of multiple rrn operons and that the transcription foci are critical for the nucleoid compaction in rapidly growing cells.

3.6.2. Active rrn Transcription Is the Driving Force for RNAP Distribution in the Cell

The bias of RNAP distribution toward the rrn operons in fast growing cells has also been observed in vivo 237. Normally, RNAP is located in the nucleoid and its surroundings in the cell 234. However, in the cell that harbors a plasmid containing an entire rrn operon, the RNAP is found largely in the cytoplasmic space suggesting that the transcription of rRNA is critical in governing the distribution/localization of the RNAP in the cell. Both the extremely strong rrn promoters and the length of the rrn operon in the plasmids are essential in driving RNAP from the nucleoid into the cytoplasm, as either the replacement of the rrn promoters with a strong ptac promoter or the shortening of the rrn operon abolishes the cytoplasmic re-localization of RNAP (Table 1). These results indicate that the two features of the rrn operons (promoter strength and transcript length) are critical in governing the distribution of RNAP in living cells.

Table 1.

RNAP distribution in cells harboring plasmid-borne derivatives of rrn Adapted from Cabrera & Jin 237

| Plasmida | rrnB (transcript length [kb]) | RNAP distribution11 |

|---|---|---|

| pBR322 | None |

|

| pNO1301 | rrnB P1-P2-16S-tRNAs-23S-5S (5.4) |

|

| pNO1302 | rrnB P1-P2-16SΔ-Δ23S-5S (2.7) |

|

| pDJ2791A | rrnB P1-P2-16S (1.8) |

|

| pDJ2791B | rrnB P1-P2-16SΔ (1.0) |

|

| pDJ2754-11 | rrnB P1-P2Δ-16S-tRNAs-23S-5S (0) |

|

| pDJ2754-17 | rrnB P1-16S-tRNAs-23S-5S (5.4) |

|

| pDJ2754-15 | rrnB P2-16S-tRNAs-23S-5S (5.4) |

|

| pDJ2845 | Ptac-16S (1.8) |

|

All plasmids are pBR322 derivatives.

The cell is reprsented by a rounded rectangle, the nucleoid by an oval. The green represents the RNAP distribution.

3.6.3. The Majority of RNAP Is Concentrated in the Transcription Foci at the Nucleolus-like Structure in Fast Growing Cells

The numbers of RNAP in E. coli cells with different growth media are estimated by different methods to range from 2000 to 5000 59,109,239,310–311. Assuming 5000 RNAP molecules/cell and ~80 bp of DNA bound by RNAP, RNAP occupies 4×105 bp or 8.7% of the E. coli genome. In rapidly-growing cells with five genome equivalents, the total coverage is reduced to 1.7%. These estimates highlight the fact that at a given time only a small fraction of the nucleoids is occupied by RNAP in fast growing cells.

The combined effects of gene dosage, long rrn transcripts and growth regulation drive RNAP allocation in the genome. In the fast growing cells (LB 37°C, DT 20 min) where rRNA is most active, assuming there are 70 RNAP per rrn, it is estimated that there are 3500 RNAP molecules transcribing a total of 50 copies of rrn (Figure 5B). Thus, about 70% of RNAP molecules are highly concentrated in the transcription foci for rrn at the putative nucleolus structure using a high estimate number of RNAP. Obviously, there are not many RNAP molecules left for the transcription of non-rrn genes in the remaining vast regions of the nucleoid during optimal growth.

The number of transcription foci on average appears to be approximating the number of nascent nucleoids in the cell (Figure 4). For example, during optimal growth (LB 37°C, DT 20 min) there are 4–5 transcription foci (Figure 4B) which correspond to 5 nucleoid equivalents per cell (Figure 5B). Imaging reveals four distinctive nascent nucleoids in the cell (Figure 4A). With a total number of 50 rrn operons in the cell, it is calculated that there are more than 12 rrn operons in each of the foci in each nascent nucleoid. Presumably, each of these dominant transcription foci is a hub of transcription activity encompassing as yet undefined transcription factories 312–313, each of which is likely actively transcribing one or more rrn operons and possibly with other highly transcribed non-rrn genes. At present, it is not clear whether non-rrn genes are also transcribed in factories. The concept of transcription hub is based on recent observations from Genome-wide Chromosome Conformation Capture analysis that in fast growing cells, highly transcribed genes are clustered and in a highly interactive environment 232. Whether all 7 rrn operons are clustered in the transcription foci is unknown. A recent study of the distribution of RNAP in superresolution suggests the presence of loner rrn that are not associated with the large clusters of RNAP 239.

3.7. Nucleoid Compaction Modulated by Transcription Foci

Several experiments described below have further demonstrated a clear correlation between the formation of transcription foci and nucleoid compaction. Together, they strongly suggest that transcription foci modulate nucleoid organization in the cell.

3.7.1. Transcription Foci Disappearance Accompanies Nucleoid Expansion during Amino-Acid-Starvation Induced Stringent Response in Wild Type Cells

The addition of serine hydroxamate (SHX) into a rapidly growing LB culture, causes starvation for serine 314 (and eventually inhibition of protein synthesis), thus inducing the stringent response 278. As expected, transcription foci disperse during the stringent response accompanied by nucleoid expansion (Figure 7). This process is reversible as transcription foci reappeared and the nucleoids were re-compacted when the culture was supplemented with the starved amino acid 234.

Figure 7.

The transcription foci disperse accompanied by nucleoid expansion during the amino-acid-starvation induced stringent response in wild type (rpoC-venus). RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP/nucleoid overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of cells growing in LB or in LB + serine hydroxamate (SHX, 30 min and 120 min) at 37°C after the induction of the stringent response. In the RNAP/nucleoid overlay, the RNAP is false colored in green and the nucleoid is false colored in red. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

3.7.2. Absence of Transcription Foci and Nucleoid Expansion in RNAP Mutants Defective in rRNA Synthesis in Nutrient-rich LB

The stringent RNAP mutants are defective in rRNA synthesis even in nutrient-rich media as described above. As expected, transcription foci are not apparent and RNAP distributes evenly across the expanded nucleoid in one of the mutant cells grown in LB (Figure 8). Consequently, the rpoB3443 (β L533P) mutant cells grow slower with a doubling time of ~40 min (LB, 37°C) which is only one half of the growth rate of wild type cells and are smaller in size compared to wild type (Figure 3).

Figure 8.

The stringent RNAP mutant cells grown in LB behave like wild type during the amino-acid-starvation induced stringent response. RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP (green)/nucleoid (red) overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of the rpoB3443 (β L533P) mutant cell containing rpoC-venus grown in LB at 37°C. The cell has no visible transcription foci and an expanded nucleoid. Cell size represents the range of cell width (W) and cell length (L) in a population (about 100 cells) of unsynchronized cells. The doubling time of this mutant strain is 40 min. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

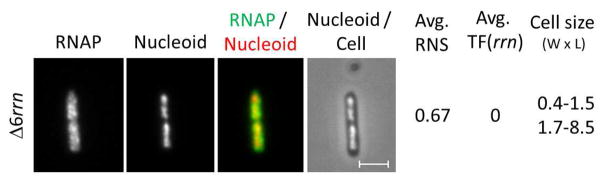

3.7.3. Lacking Transcription Foci and Expanded Nucleoid in Δ ΔΔ6rrn Mutant Cells

When six of the seven rrn operons in the chromosome are deleted, the resulting Δ6rrn mutant has a slow growth rate with a doubling of ~34 min in LB at 37°C. There are no apparent transcription foci and the nucleoid is expanded with an RNS value of 0.67 (Figure 9). Based on the growth rate, it is calculated that there are four rrn on average per cell. These results suggest that formation of transcription foci with multiple rrn is required for nucleoid compaction 235.

Figure 9.

The presence of multiple rrn operons is critical for the formation of transcription foci and nucleoid compaction. RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP (green)/nucleoid (red) overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of the Δ6rrn mutant cell containing rpoC-venus that has only one rrn operon (rrnC) remaining on the chromosome grown in LB at 37°C. There are no apparent transcription foci and the nucleoids are expanded in the mutant cells. Cell size represents the range of cell width (W) and cell length (L) in a population (about 100 cells) of unsynchronized cells. The doubling time of this mutant strain is 34 min. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

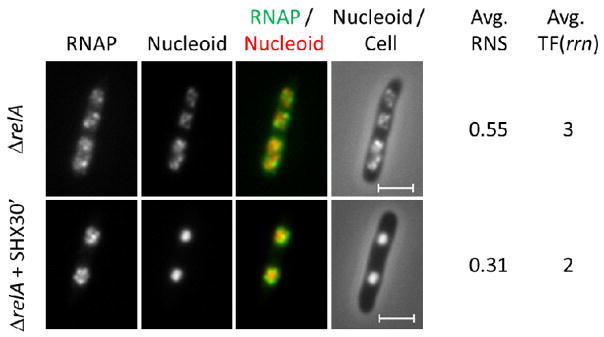

3.7.4. Apparent Transcription Foci and Nucleoid Compaction in the “Relaxed” relA Mutant Cells during Amino-Acid Starvation

Unlike wild type, the relA mutant is defective in the production of (p)ppGpp during amino acid starvation 280,315; thus it is proficient in rRNA synthesis with the addition of SHX in LB culture. Transcription foci are apparent during amino acid starvation and the nucleoids are further compacted (Figure 10). Apparently the two nascent nucleoids in each half of the cell are fused together and DNA appears to be highly condensed with an average RNA value of 0.31, a phenotype that resembles that of the nucleoids in cells treated with the protein inhibitor chloramphenicol (see below). Note that the cells cease to grow after the addition of SHX owing to inhibition of protein synthesis. Inhibition of translation could reduce the coupling of transcription-translation and transertion, which in turn could cause nascent nucleoid fusion and further condensation compared to untreated cells. Under this condition active rRNA synthesis decoupled from cell growth still has an impact on the nucleoid.

Figure 10.

The transcription foci are apparent and the nucleoids are hyper-condensed in the “relaxed” ΔrelA mutant cells during amino acid starvation induced by SHX. RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP/nucleoid overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of the mutant cells containing rpoC-venus grown in LB or in LB + SHX for 30 min at 37°C. In the RNAP/nucleoid overlay, the RNAP is false colored in green and the nucleoid is false colored in red. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

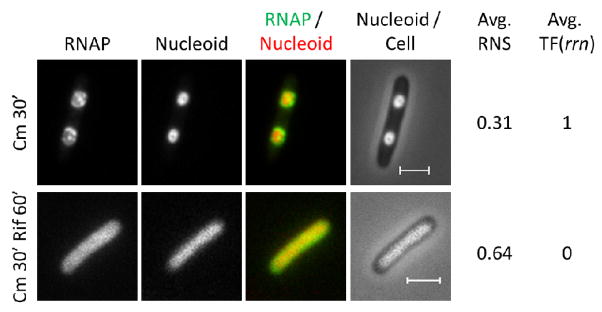

3.7.5. Evident Transcription Foci and Nucleoid Compaction in Cells Treated with Protein Synthesis Inhibitors

When rapidly growing cells in LB are treated with chloramphenicol or spectinomycin, cell growth stops immediately. Both antibiotics have the same effect on transcription foci and nucleoid compaction. As shown in figure 11, the transcription foci remain evident and nucleoids become further compacted. Similar to the morphology of the nucleoids in the relA mutant cells treated with SHX (Figure 10), the fused nascent nucleoid in each half of the cell is highly condensed with the same average value of RNS (0.31) in chloramphenicol-treated cells.

Figure 11.

The hyper-condensed nucleoids in chloramphenicol-treated cells depend on active transcription. RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP/nucleoid overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of wild type cells containing rpoC-venus after chloramphenicol treatment for 30 min or sequential treatment of chloramphenicol for 30min followed by an additional rifampicin treatment for 60 min. The hyper-condensed nucleoids and the transcription foci are apparent in chloramphenicol-treated cells. With the additional rifampicin treatment, however, the foci disappear and the nucleoids expand. In the RNAP/nucleoid overlay, the RNAP is false colored in green and the nucleoid is false colored in red. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

Chloramphenicol treatment enhances nucleoid compaction as indicated by increased sedimentation of the isolated nucleoid 76. Nucleoid compaction in chloramphenicol-treated cells has been used as evidence for the hypothesis that transertion is an expansion force for the nucleoid, thus inhibition of protein synthesis leading to the inhibition of transertion results in nucleoid compaction 55. In wild type cells treated with SHX, protein synthesis and transertion are inhibited; however, the nucleoids are fully expanded (Figure 7). These results are not consistent with the hypothesis that transertion is a nucleoid expansion force. Furthermore, with the additional treatment of rifampicin that inhibits transcription, the nucleoids compacted by chloramphenicol convert to expanded ones accompanied with the disappearance of transcription foci 235 (Figure 11). Together, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that transcription foci modulate nucleoid compaction.

3.8. Transcribing RNAP Locates at the Surface of the Nucleoid

As described below, co-imaging RNAP and the nucleoid in cells containing rpoC-venus under different growth conditions reveals new features and details. Analysis of the overlays (RNAP/Nucleoid) has provided new insights on how RNAP remodels nucleoid organization.

3.8.1. Transcription Foci Appear to Position at the Voids of the Nucleoid

Overlay of the images of RNAP and the nucleoid from cells during optimal growth shows that transcription foci tend to locate at the apparent voids of the nucleoid where DNA densities are low (Figures 4 &7). This feature suggests that highly active transcription foci for rrn and possibly other genes are in a distinct compartment separated from the main body of the nucleoid. As most of the RNAP molecules are concentrated in the transcription foci, larger areas of the nucleoid are devoid of RNAP as indicated by red color in the overlay of the two images, consistent with the hypothesis that RNAP is limited and mainly engaged in rRNA synthesis during fast growth.

3.8.2. DNA Loops Enriched with RNAP locate at the Periphery of the Nucleoid

One common theme from the overlays of the RNAP and DNA images is that the area covered by RNAP signal is usually larger than that of the nucleoid signal. This is particularly evident for the nucleoids without transcription foci such as Δ6rrn (Figure 9) and wild type cells treated with SHX for 30 min (Figure 7). Because RNAP is a strong DNA binding protein and is always associated with DNA in the cell 131, we speculate that the enlarged RNAP areas suggest the presence of DNA loops at the periphery of the observed nucleoid. It seems very likely that DNA loops are the main locations for transcription in the nucleoid. The DNA densities of the loops are likely too low to be detected by conventional fluorescence microscopy. Super-resolution imaging is necessary to reveal more details on these features.

The inverse relationship between RNAP and nucleoid can be better observed when the nucleoids isolated from the lysed cells are analyzed (Figure 12). In the isolated nucleoids from fast growing cells (LB), the transcription foci are at the periphery of the nucleoid where DNA density is low. The overlay image shows a distinct pattern of green (RNAP) or red (DNA) but not much of orange that would be indicative of co-localization (RNAP/DNA). As described in the previous section (2.3.3.2), there are temporal changes in nucleoid structure in cells during a hyper-osmotic stress response. The nucleoids become hyper-condensed shortly (10 to 20 min) after initial high salt shock followed by gradually remodeling and returning to the pre-stress state during the later adaptation stage. Accompanying the changes of the nucleoid structure, RNAP initially dissociates from the nucleoid releasing into the cytoplasmic space followed by re-associates with the nucleoid 131. The nucleoids isolated from the cells 20 min after the salt shock is hyper-condensed (NaCl 20 min) similarly to that in the intact cells (Figure 2). At this time, RNAP associates (being crosslinked) with the unseen DNA loops and forms a distinct ring at the periphery of the isolated nucleoid. As this is a 2-D image, it indicates a sphere of RNAP associated with DNA loops surrounding the nucleoid. These observations are consistent with the preferential binding of RNAP to DNA loops at the periphery of the nucleoid.

Figure 12.

The nucleoids released from lysed cells highlight the presence of RNAP on the peripheral DNA loops. The nucleoids of exponential phase cells grown in LB or after an osmotic stress (0.5M NaCl) for 20 min and 60 min are isolated and imaged. RNAP, nucleoid and overlay of RNAP (green) and nucleoid (red) are shown. In LB, the transcription foci appear to be located in the voids or low density regions of the compact nucleoids. After induction of the osmotic response, the initially released RNAP re-associates to DNA loops at the periphery of the hyper-condensed nucleoid, forming a sphere of RNAP surrounding the nucleoid. After 60 min, the nucleoids approximate the pre-stress sate and RNAP is enriched at the periphery of the nucleoids. The scale bar represents 2 mm. Reproduced from Cagliero & Jin 131.

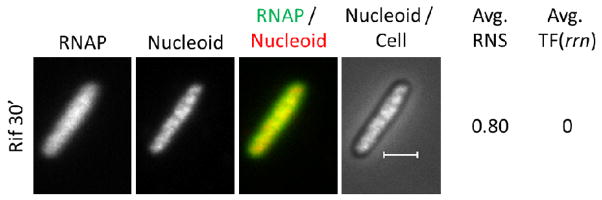

3.8.3. Non-Transcribing RNAP Scatters across the Nucleoid

In the presence of rifampicin, which inhibits transcription initiation 316 but not DNA binding 317, the nucleoid expands fully and RNAP redistributes relatively homogeneously across the nucleoid to promoters and non-specific sites 318–319, as indicated by minimum texture variation of the RNAP image (Fig. 13). The number of sites occupied increases more than 5-fold compared to untreated cells 320; similar morphology is observed in cells treated with SHX for 2 hrs (Figure 7). These results are in agreement with the early observations that isolated nucleoids from cells treated with rifampicin or amino acid starvation exhibit reduced sedimentation compared to untreated cells 21,76 as mentioned in the last section (2.3.1.2).

Figure 13.

Inhibition of transcription by rifampicin causes RNAP to evenly scatter across the nucleoid and the nucleoid to fully expand. RNAP, nucleoid, RNAP/nucleoid overlay and nucleoid/cell overlay of wild type cells after rifampicin treatment for 30 min. In the RNAP/nucleoid overlay, the RNAP is false colored in green and the nucleoid is false colored in red. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

4. Model: Transcription Foci Condense the Nucleoid

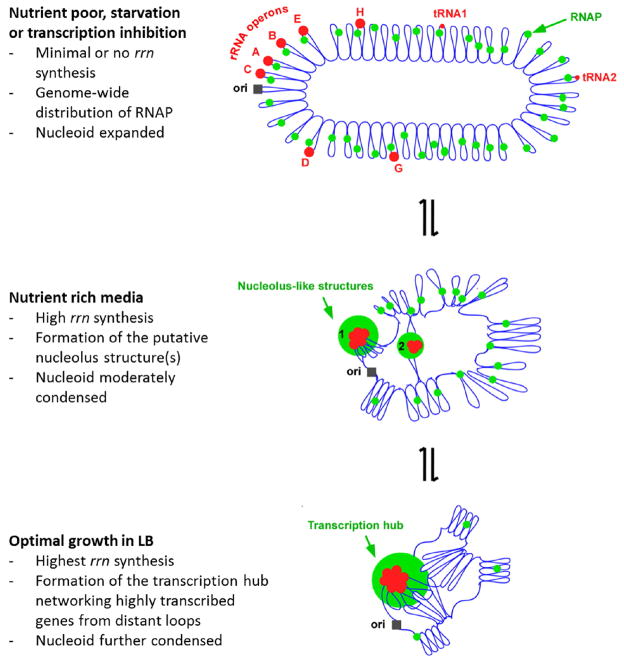

How do RNAP and transcription influence nucleoid organization? A model is proposed to explain how transcription and particularly transcription foci are intimately linked to the structure of the nucleoid (Figure 14). The presence of transcription foci and the structure of the nucleoid are both highly dynamic and are largely affected by growth conditions and stress. This model is based on the premise that RNAP is limited and cannot sustain both active rrn synthesis and genome-wide transcription at the same time 288 and modified from the ones described previously 14,186,234.

Figure 14.

A model illustrating how transcription foci compact the nucleoid in fast growing cells in LB. The nucleoid organization is dynamic and sensitive to the pattern of RNAP distribution which responds to changes in growing environments. The E. coli chromosome is represented as blue lines folded in loops, the ori of replication as a black square, the seven rRNA operons as large red circles with letters, and two representative tRNA operons as small red circles. The RNAP molecules are represented as small green circles. In very slow growing or nutrient starved cells (top), RNAP distributes relatively evenly across the nucleoid for broad global gene expression leading to the full “open” state of the nucleoid or nucleoid expansion. Inhibition of transcription by rifampicin has a similar effect on the nucleoid because RNAP scatters across the nucleoid homogenously. During rapid growth (middle), RNAP is concentrated at the putative nucleolus structures (~1% of the genomic DNA) and biased for rRNA synthesis, leaving only a small fraction of RNAP in the vast remaining regions of the nucleoid, leading to nucleoid compaction. For simplicity, only two nucleolus-like structures which make the nucleoid more compact by pulling different rrn operons (red cluster) into proximity in a nascent nucleoid are shown. During optimal growth (bottom), the transcription foci represent transcription hubs networking with the transcription of other genes located in distant loops, further condensing the nucleoid. The transcription hub is indicated. See text for details.

In fast growing cells, the nucleoid compaction is mediated by the formation of the transcription foci. The extremely active rrn transcription acts as a driving force for RNAP distribution in the cell 237, thus, titrating RNAP away from transcription of the majority non-rrn genes in the genome. Extremely high expression of rrn is also likely to impose the supercoiled domains in the region. Formation of transcription foci with multiple highly transcribing rrn operons could be facilitated by depletion-attraction 73 or other unknown mechanisms. TF(rrn) are centered at nucleolus-like organization and located at the periphery of the nucleoid in low density DNA regions, supporting the idea of a subcellular compartmentalization. Like other hyperstructures 321, subcellular compartmentalization of the foci would have logistic advantages, including maximizing efficiency of transcription, coupling rRNA synthesis with processing and ribosome assembly and reducing traffic jams. Also importantly, the “imprinted” transcription foci at each of the nascent nucleoids would retain active rRNA synthesis apparatuses upon cell division to sustain fast growth.

Additionally, as suggested by the recent E. coli Genome-wide Chromosome Conformation Capture analysis 232, the transcription foci could represent a hub of transcription factories encompassing multiple rrn and non-rrn genes, including essential and growth-related genes located in distant DNA loops of the nucleoid. An average size of DNA loops being 10 kb 171 could easily reach a few μm distances for networking with the transcription hub. Bridging of intra- and/or inter-loops by small NAPs and transcription factors 26,322 could enhance the networking. The hub and networking could maximize the use of the limited RNAP by sharing as a pool, as RNAP released from “run off” in the hub could hop around three-dimensionally in search of promoters 158. The transcription foci networking of distant DNA loops could further create tension promoting a higher order of the nucleoid compaction and organization.

Finally, the basic nucleoid organization is in a dynamic equilibrium between the “closed” and “open” states. Transcription activities promote the “open” state generating supercoiling loops at the surface of the nucleoid, resembling eukaryotic re-modeled nucleosomes active for transcription. RNAP dissociation or minimal transcription favors the “closed” state with a high density of DNA in the core interior of the nucleoid, analogous to the un-remodeled nucleosomes. In fast growing cells, only a relatively small fraction of the genome is highly transcribed, the vast majority of regions of the nucleoid are devoid of transcription and RNAP, leading to global nucleoid compaction. During nutrient limitation or stress, the transcription from the rrn operons is reduced to a minimum, thus destabilizing the transcription foci and reducing the supercoiling in the region. The loops that were associated with the hubs will disperse and the tension is lost, leading to nucleoid relaxation or expansion. In addition the re-distribution of RNAP enables transcription of larger fractions of the genome, thus encompassing more of the “open” state. Inhibition of transcription by rifampicin causes the nucleoid to fully expand maximizing the “open” state because the “run off” RNAP scatters across the nucleoid homogenously.

This model could explain the effects of growth conditions and antibiotics treatments on nucleoid structure reported in the literature. It also provides the framework for further studies on the mechanism whereby RNAP and transcription remodels the nucleoid.

5. Conclusion and Perspectives

In the nucleoid, which appears to be largely devoid of tightly-bound proteins, RNAP is the predominant protein and binds to DNA most strongly among all NAPs. Formation of transcription foci accompanies nucleoid compaction, which is the central feature of the nucleoid structure in fast growing cells. It is postulated that the transcription foci acts as hubs for networking gene expression in distant loops, which in turn generates tension for a higher order of nucleoid compaction. Transcription and networking are likely influenced by small NAPs and transcription factors. Thus, the presence or absence of transcription foci will influence the organization of the nucleoid, including compaction and expansion in response to changes in growth and cell cycle. Furthermore, the compartmentation and “imprint” of transcription foci in the nucleoid have important implications for growth regulation, cell cycles and other chromosome functions in E. coli.