Abstract

A large fraction of the marine bacterioplankton community is unable to form colonies on agar surfaces, which so far no experimental evidence can explain. Here we describe a previously undescribed growth behavior of three non-colony-forming oligotrophic bacterioplankton, including a SAR11 cluster representative, the world's most abundant organism. We found that these bacteria exhibit a behavior that promotes growth and dispersal instead of colony formation. Although these bacteria do not form colonies on agar, it was possible to monitor growth on the surface of seawater agar slides containing a fluorescent stain, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Agar slides were prepared by pouring a solution containing 0.7% agar and 0.5 μg of DAPI per ml in seawater onto glass slides. Prompt dispersal of newly divided cells explained the inability to form colonies since immobilized cells (cells immersed in agar) formed microcolonies. The behavior observed suggests a life strategy intended to optimize access of individual cells to substrates. Thus, the inability to form colonies or biofilms appears to be part of a K-selected population strategy in which oligotrophic bacteria explore dissolved organic matter in seawater as single cells.

Formation of a biofilm or colony by bacteria is a behavior that allows prompt utilization of the substrate. The combined exoenzymatic action of a growing colony provides benefits to the individual cells when there is a rich food supply. Alternatively, an oligotrophic bacterioplankton growing slowly in a nutrient-poor environment may have a life strategy in which dispersal is promoted to optimize cell access to substrates. In the latter scenario the formation of colonies is probably not adaptive. These two different life strategies may explain the thousand-fold difference between the total number of bacteria and the number of CFU found in typical seawater samples. Over the years the discrepancy in these numbers has puzzled many authors (13). Clearly, dead and dying bacterial cells cannot form colonies; thus, the effects of virus infection and nutrient starvation have been inferred to be reasons for low viable counts (14, 19, 24). Furthermore, different states of bacterial cell physiology, such as dormancy and the so-called viable but not culturable state, have been suggested to be explanations for the lack of growth on solid media (20, 26). However, the behaviors of bacteria with different life strategies have not been considered in relation to the formation of colonies.

In this study we used the dilution-to-extinction technique (6) to isolate bacterial strains unable to grow and form colonies on conventional culture media. In an attempt to understand this inability to grow and form colonies, we explored the growth behavior of three marine bacterioplankton species by using a novel assay. Bacteria were grown on seawater agar slides containing a fluorescent stain, which allowed direct observation by epifluorescence microscopy of living cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Seawater was collected at a depth of 2 m in the Baltic Sea (57°27′N, 17°05′E) on 6 August 2002 and in the Skagerrak Sea (58°15′N, 11°22′E) on 25 September 2002 and 14 February 2003 by using a 10-liter Niskin bottle. The samples were stored in 5-liter polycarbonate bottles that were transported in a seawater-filled cooler box. The time from sampling to inoculation of dilution plates did not exceed 1.5 h.

Isolation of oligotrophic bacterioplankton.

The dilution-to-extinction method for culturing and isolating oligotrophic bacteria with 96-well culture plates (Falcon) was modified as described by Button et al. (6). Seawater was collected at the sampling sites and prepared for use in media on the day prior to sampling. The medium water was filtered (47-mm-diameter, 0.2-μm-pore-size Supor-200 filter; Pall Corporation) and autoclaved. The use of autoclaved seawater as a medium for growth of marine bacteria has been described previously (3, 12). The total number of bacteria was determined by microscopy. Seawater was filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size black polycarbonate filter and stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (final concentration, 4 μg/ml; Sigma), and cells were counted with an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan) (22). Seawater diluted to contain 2,048 cells (accurate within 5% depending on the uncertainty of the total count) in 200 μl of seawater medium was added to the first row of a 96-well plate. Twofold dilutions were done to the 12 successive rows of the plate. After the dilution procedure was complete, 100 μl of seawater medium was added to all of the wells except the wells in the last row. This meant that at least eight potential pure cultures originating from a single cell could occur on each plate. The culture plates were incubated for 3 weeks at 15°C with a cycle consisting of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. The screening procedure used for the dilution culture plates has been described elsewhere (7). Potential pure isolates screened by microscopy were transferred to 10 ml of seawater medium and grown for an additional 3 weeks (Fig. 1A). Pure cultures were expected only in the dilution wells with the smallest inoculum (i.e., rows 5 to 12 of the 96-well plates depending on the culturability of the inoculum). After sequencing, all mixed cultures, as detected with an electropherogram of the sequencing reaction mixture, were discarded (Table 1). This did not eliminate the possibility that a contaminant which was a minor component could have been present in a selected culture. The isolates were therefore subjected to a further dilution to extinction to ensure purity.

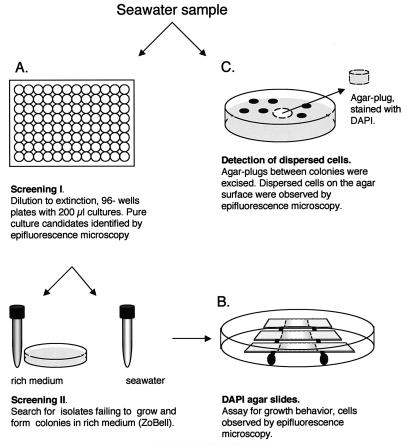

FIG. 1.

Experimental setup.

TABLE 1.

Screening for oligotrophic bacterioplankton cultures

| Sample | Total no. of wells inoculated | No. of cultures detected in screening I | Screening II

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cultures showing growth in rich medium | No. of oligotrophic bacterioplankton culture candidates | No. of mixed culturesa | No. of cultures lost during transferb | No. of cultures not identified | No. of sequenced oligotrophic cultures | |||

| Baltic Sea | 192 | 22 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 5 |

| Skagerrak Sea | 384 | 77 | 9 | 68 | 3 | 43 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 576 | 99 | 13 | 86 | 7 | 52 | 11 | 16c |

Based on mixed sequences.

Cultures did not grow after transfer, or DNA could not be extracted.

Sequenced isolates minus duplicates are shown in Table 2.

DNA extraction and sequencing.

DNA from selected isolates was extracted from 1.5 ml of a culture (in seawater medium) that was harvested by centrifugation (15 min at a relative centrifugal force of 20,800). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 175 μl of lysis buffer (400 mM NaCl, 750 mM sucrose, 20 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl; pH 9.0) and incubated with lysozyme (final concentration, 1 mg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (final concentration, 1%; Sigma) and proteinase K (final concentration, 100 μg/ml; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) were added, and the samples were incubated at 55°C overnight. Sodium acetate (0.1 volume; 3 M; pH 5.2) was added before the DNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of 99.5% ethanol. Samples were resuspended in 1× Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0). The 16S rRNA gene was PCR amplified by using primers 27F and 1492R (15) and was subsequently sequenced by using primers 27F, 518r, and 907r (10, 15). The sequences were obtained by using a DYEnamic ET terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences) and an ABI PRISM 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturers. Information concerning the phylogenetic similarity of the resulting 11 unique oligotrophic cultures was obtained from GenBank by using the BLAST tool (2; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

DAPI-stained agar slides.

Seawater-based agar (0.7%; A-9539; Sigma) containing DAPI (0.5 μg/ml) was poured on glass slides. By using a pipette the agar solution, which was kept at 42°C, was added to the limit of surface tension on the glass slide. A sterile cover glass (24 by 32 mm) was placed on the molten agar; this resulted in an agar layer thickness that reproducibly stayed within a narrow range (∼1 mm). The cover glass was removed from the solid agar, which left a flat surface. A drop of culture (10 μl; ∼1 × 105 cells/ml) was placed onto the middle of the flat surface with a pipette. Slides were incubated in petri dishes on wet paper disks. Each day slides were sacrificed, and a cover glass (24 by 32 mm) was placed on top of each agar surface for microscopic counting. When the initial drop of culture was absorbed by the agar, the cells accumulated at the edge of the drop. Microscopic counts were obtained by examining the circumference of the ring formed by the drop. In this manner the relative increase in numbers could be recorded. At least 30 microscopic fields were counted.

Microscopic observation of agar plugs.

The presence of dispersed bacteria on agar surfaces was determined by microscopy. Agar plugs from between the colonies were obtained by punching the agar with the backside of a Pasteur pipette (Fig. 1C). A 1-mm slice of each plug was placed on a glass slide and stained for 15 min with DAPI through diffusion (1 μg of DAPI per ml added in a drop next to the agar plug). The preparation was sealed with a cover glass before microscopy.

PCR amplification.

To determine the accumulation of SAR11 16S rRNA genes on agar plates, real-time quantitative PCR was used. The presence of non-colony-forming strain SAR11 on the ZoBell agar surface was determined by first removing all visible colonies with a Pasteur pipette; then the remaining cells were collected by repeated washing of the agar (two washes with 2 ml of 1× Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0). DNA was extracted by using the protocol described above. DNA was extracted from the water used as the inoculum for the plates by filtering 50 ml of seawater onto a 25-mm-diameter, 0.2-μm-pore-size Supor-200 filter (Pall Corporation) and was treated as described above. The real-time quantitative PCR assay with the SAR11-specific primer probe set was performed as described by Suzuki et al. (27) by using a sequence detection system (ABI PRISM 7700; Applied Biosystems). A linear plasmid containing genomic 16S ribosomal DNA from a member of the SAR11 cluster, clone KRB2 (closest neighbor, HTCC1062 [7]), was used as the standard. End point PCR was performed by using SAR11-specific primers Sar-f (5′-GCAATACTTAGTGGCAGACGGG) and SAR-r (5′-CGTTTACGGCATGGACTACGA), which resulted in a 690-bp fragment.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of 11 unique oligotrophic cultures have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AY317112 to AY317119 and AY317121 to AY317123.

RESULTS

To determine the growth behavior of oligotrophic bacterioplankton, bacterial isolates were collected by the dilution-to-extinction technique (6) (Fig. 1A). Six 96-well plates, two for the Baltic Sea proper and four for the Skagerrak Sea, were screened for possible pure seawater cultures by using epifluorescence microscopy. Bacteria from wells in which microscopy showed that there was uniform cell morphology were treated as potentially pure cultures. The candidates (22 Baltic Sea cultures, 77 Skagerrak Sea cultures) were each transferred to two tubes (10 ml), one with seawater medium and one with rich medium (ZoBell), and plated on ZoBell agar (29). Growth was recorded after 14 days of incubation at 15°C. Oligotrophs were selected by using the following criteria: the organisms grew in seawater, were not able to form colonies on solid media, and did not grow in rich liquid medium (ZoBell). These criteria were met by 86 of the 99 candidates (Table 1). Further screening resulted in 11 oligotrophic isolates which were sequenced (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Phylogenetic information and accession numbers for previously uncultured marine oligotrophic isolates

| Isolate | Accession no. | Nearest neighbor in GenBank database (accession no.) | Phylogenetic affiliation | % Similarity | No. of nucleotides compared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAL58 | AY317112 | Antarctic bacterium R-8890 (AJ440995) | Proteobacteria; β-proteobacteria | 95 | 1,367 |

| BAL59 | AY317114 | Clone GKS9 (AJ224990) | Proteobacteria; β-proteobacteria; environmental samples | 97 | 590 |

| BAL60 | AY317113 | Clone GCPF3 (AY129780) | Actinobacteria; Actinobacteridae; Actinomycetales; Propionibacterineae; Nocardioidaceae; Nocardioides; environmental samples | 96 | 404 |

| SKA48 | AY317115 | Clone Arctic 96A-7 (AF353226) | Proteobacteria; α-proteobacteria; environmental samples | 100 | 580 |

| SKA49 | AY317116 | Pelagibacter strain HTCC1062 (AF510191) | Proteobacteria; α-proteobacteria; Rickettsiales; SAR11 cluster; Candidatus Pelagibacter | 99 | 422 |

| SKA50 | AY317117 | Cytophaga sp. (AB015262) | Bacteroidetes; sphingobacteria; Sphingobacteriales; Flexibacteraceae; Cytophaga | 92 | 880 |

| SKA51 | AY317118 | Clone CRE-PA44 (AF141524) | Bacteroidetes; sphingobacteria; Sphingobacteriales; environmental samples | 98 | 493 |

| SKA52 | AY317119 | Clone OM55 (U70681) | Planctomycetes; Planctomycetacia; Planctomycetales; environmental samples | 100 | 520 |

| SKA54 | AY317121 | Clone OM42 (U70680) | Proteobacteria; α-proteobacteria; environmental samples | 99 | 437 |

| SKA55 | AY317122 | Clone OM65 (U70682) | Proteobacteria; α-proteobacteria; environmental samples | 99 | 430 |

| SKA56 | AY317123 | Clone OM182 (U70699) | Proteobacteria; γ-proteobacteria; environmental samples | 97 | 489 |

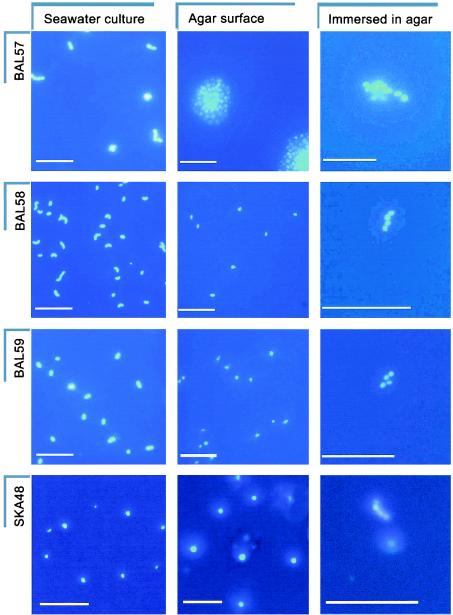

Although the oligotrophic isolates did not form visible colonies, they could have formed small aggregates (i.e., microcolonies consisting of four or more cells) that were visible only by microscopy. This growth behavior was tested by inoculating seawater agar slides containing DAPI (final concentration, 0.5 μg/ml) (Fig. 1B). In this way live bacteria could be viewed during growth on a solid surface. Observation of three oligotrophic isolates, one member of the alpha subclass of the Proteobacteria (α-proteobacteria) (SKA48) and two β-proteobacteria (BAL58 and BAL59), on DAPI-agar slides revealed that growth did occur on solid media, although the oligotrophs were unable to form colonies like those of control isolate BAL57 (Fig. 2). Instead, cells were found to be dispersed over the agar surface. The relative increases in cell numbers on the agar slides were determined by microscopic counting, and Table 3 shows the apparent growth rates on the agar surfaces compared to those in liquid media. To immobilize the growing cells, the cultures were immersed in agar. Thus, the cells could not disperse, and this resulted in small microcolonies of isolates BAL58, BAL59, and SKA48 (Fig. 2). The small number of cells in these microcolonies was expected due to the low growth rate and the deteriorating growth conditions.

FIG. 2.

Growth behavior of marine bacterioplankton. One colony-forming control isolate, BAL57 (Cytophaga sp.) and three oligotrophic bacteria, BAL58 (β-proteobacterium), BAL59 (β-proteobacterium), and the SAR11 clade member SKA48 (α-proteobacterium), were grown (i) in seawater cultures (images show cells stained with DAPI on 0.22-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters), (ii) on agar surfaces (cells were grown on DAPI-containing seawater agar slides), and (iii) immersed in agar (cells were grown in seawater agar containing DAPI). Observations were made by epifluorescence microscopy. Bars = 10 μm. Some of the images were digitally enlarged for readability; therefore, comparisons of cell size may be misleading due to the sizes of the variable halos.

TABLE 3.

Growth characteristics and phylogenetic relationships of selected marine bacterioplanktona

| Isolate | Accession no. | Nearest neighbor in GenBank database | Growth rate (day−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seawater | Rich medium | Solid surface | |||

| BAL58 | AY317112 | β-Proteobacterium A0637 (AF236004) | 0.52 | 0.27 | |

| BAL59 | AY317114 | β-Proteobacterial environmental clone GKS98 (AJ224990) | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.36 |

| SKA48 | AY317115 | Uncultured α-proteobacterial clone Arctic 96A-7 (AF353226) | 0.40 | 0.01 | |

| BAL57 | Cytophaga sp. strain SKA31 (AF261053) | 0.73 | 0.93 | ||

Three non-colony-forming isolates (BAL58, BAL59, and SKA48) and one colony-forming control isolate (BAL57, identical to SKA31) were grown in seawater medium, in rich liquid medium (ZoBell), and on ZoBell agar plates.

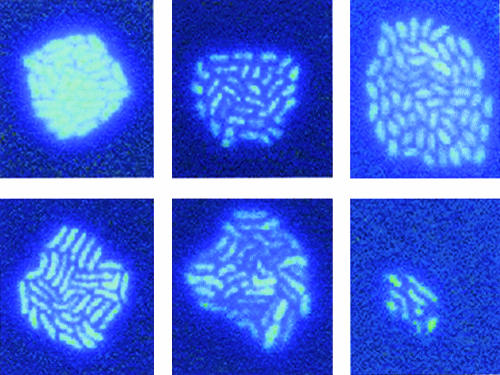

The very low growth rate of the α-proteobacterial isolate on the agar surface (Table 3) might have been an indication that the DAPI stain affected the cells, although the bacterial cells in general did not appear to be severely affected by the presence of DAPI (as judged from the regular cell shapes and no signs of lysis). When Skagerrak Sea water was inoculated onto DAPI-agar slides, several different shapes of microcolonies readily formed (Fig. 3). In the case of BAL57 (Cytophaga sp.), colonies with regular shapes formed on the agar slides (Fig. 2); however, when the organism was grown in liquid media (ZoBell) with increasing concentrations of DAPI, the growth rate was reduced when the final DAPI concentration was more than 0.5 μg/ml (data not shown). Still, this concentration of DAPI was sufficient to stain the bacteria with high contrast.

FIG. 3.

Microcolonies formed by marine bacterioplankton from a seawater sample (Skagerrak Sea) inoculum. The images represent different shapes of microcolonies grown on seawater agar slides containing DAPI (0.5 μg/ml). Magnification, ×1,250.

In a separate dilution experiment, the possible effect of DAPI on colony formation was investigated further. Skagerrak Sea water (collected on 5 May 2003) was used to inoculate a 96-well plate, which was treated and incubated as described above. Samples from all wells on this plate were transferred to ZoBell agar plates and DAPI-agar slides. In addition, DNA was extracted from each well and amplified by PCR by using 16S ribosomal DNA primers (15). The results showed that DNA could be amplified from all 54 wells in which growth was detected by microscopy. Only eight wells produced colonies on ZoBell agar, but only bacteria from these wells also formed microcolonies on agar slides. Therefore, the effect of DAPI on the formation of colonies was considered to be negligible. However, to deal with additional concerns about DAPI stain affecting growth, another set of slides was cultured without DAPI and stained after incubation. Staining was done by allowing DAPI to diffuse from the sides of the agar. Identical growth patterns were observed (data not shown), but the staining of the cells was slightly less intense when this procedure was used.

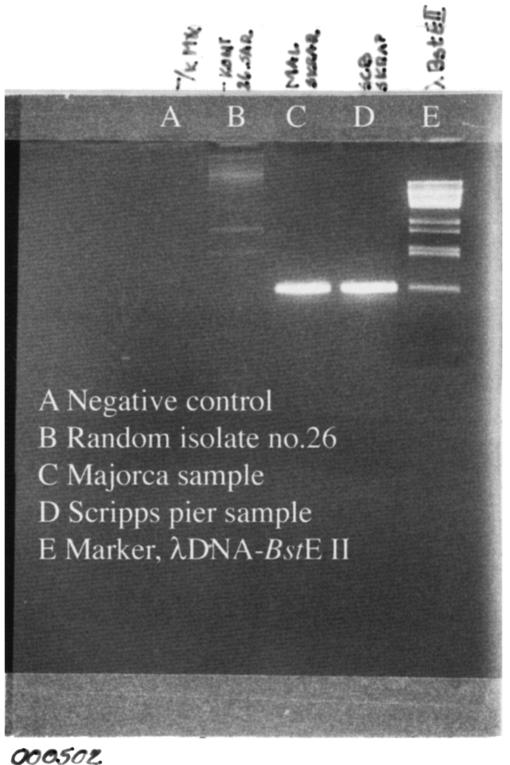

The results obtained with the agar slides suggested that growth of a natural mixture of bacteria from a seawater sample produces cells that grow as colonies and as oligotrophic individuals dispersed on the agar surface. In an attempt to test this hypothesis, we used real-time quantitative PCR with a specific primer-probe set for the oligotrophic archetype SAR11. Agar plates with water from the Skagerrak Sea (collected on 14 February 2003) were incubated for 14 days at 15°C. DNA for analysis of dispersed SAR11 cells on the agar surface was obtained by first removing agar plugs containing all visible colonies and then extracting DNA from the remaining agar surface. A significant increase in SAR11 16S rRNA genes was detected when the inoculated agar plates were compared to the plates incubated with autoclaved seawater as a negative control (mean difference in Ct values, 3.5 ± 0.5; n = 9). However, since the efficiency of extraction (including the removal of cells from the agar) was difficult to determine, it was not possible to compare the amount of SAR11 16S rRNA genes accumulated on the plates to the initial amount of community DNA. End point PCR produced visible bands from the DNA extracts of the agar surface, as well as from the seawater inoculum (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in previous experiments with water samples collected off Scripps Pier and in the western Mediterranean Sea (Fig. 4). None of the visible colonies from the agar plates tested positive for SAR11. This indicated that although the so-called unculturable strain SAR11 did not form visible colonies, it was present on the agar surface.

FIG. 4.

End point PCR amplification of DNA extracted from the entire surface growth on agar plates inoculated with seawater samples obtained off Scripps Pier, Southern California Bay, and from the Alcudia Bay, Majorca, in the Mediterranean Sea. Plates were incubated at 15°C for 2 weeks.

The presence of dispersed bacteria growing on ZoBell agar plates that were inoculated with 100 μl of Skagerrak Sea water was confirmed by microscopic counting. After 14 days of incubation at 15°C, agar plugs were obtained from between the colonies by punching the agar with the backside of a Pasteur pipette, and the plugs were stained with DAPI by diffusion (Fig. 1C). The number of dispersed bacteria on the surfaces of the three plates (three replicates from each plate) had increased from the initial number, 30 ± 11 cells mm−2 (n = 9), to 330 ± 110 cells mm−2 (n = 9). This increase corresponds to a growth rate of 0.24 day−1. Compared to the growth rate reported for the first member of the SAR11 clade isolated, strain HTCC1062, this value appears to be low. However, this rate estimate depended heavily on the culturability (that is, the percentage of viable cells added to the plates). According to Morris et al. (18), the culturable fraction of the oligotrophic bacteria may be as low as 1.5 to 15%. A control experiment was also performed with known bacterial strains representing colony-forming bacteria, including Flavobacterium sp. strain BAL4 (accession number U63936), Roseobacter sp. strain SKA44 (accession number AF261065), Agrobacterium sp. strain SKA42 (accession number AF261063), and Sphingomonas sp. strain BAL8 (accession number AF182029), and one swarming bacterium, Colwellia sp. strain KAT2 (accession number AF025315). ZoBell agar plates were inoculated with dilute liquid cultures of the different control strains. The plates were incubated until colonies formed, and plugs were excised from between the colonies as described above. Dispersed cells were not detected between the colonies for any of the strains tested (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

From the results obtained in this study it became clear that some bacteria have a behavior that can explain their inability to form colonies on agar plates. Even if slow growth in itself could prevent formation of visible colonies on agar plates, the oligotrophic isolates tested did not form microcolonies of any kind; instead, dispersal of single cells was the most evident behavior.

Laboratory bacteria usually form colonies or grow so that they produce visible turbidity in rich liquid media, and microbiologists have come to regard this as the norm for bacterial presence. The standard rule for Escherichia coli colonies is to maximize cell-to-cell contact (i.e., population density) rather than access of individual cells to the substrate (25). As a consequence, two E. coli daughter cells elongate alongside each other unless one of the sibling bacteria is attracted by a third nearby bacterium. Our observations of microcolony growth on seawater agar slides are consistent with this behavior, and it was striking that cells never adhered to the colonies with their ends but always adhered alongside each other (Fig. 3). It seems likely that colony-forming behavior provides the basis for a life strategy in which the attraction between bacteria boosts the enzymatic action of the combined cells. A second life strategy complementary to the formation of colonies is to promote rapid utilization of an entire surface through swarming. In this case the colony extends in the form of a swarm of cells that effectively invade a food resource; this occurs in the case of Proteus and Serratia (9). A third life strategy can be anticipated in the aquatic environment, where free-living bacteria have the option to explore the dissolved organic matter continuum lacking surfaces. This environment, as envisioned by Azam (5), consists of organic matter ranging from the size of monomers to strings and aggregates of biopolymers that produce a microscopic matrix in the water, which promotes single-cell dispersal instead of colony formation by bacteria.

Based on the oligotrophic isolates described in this paper, we concluded that bacterioplankton that employ the third strategy are slow growing, small, free living, and unable to form colonies. The generation time for the isolates described in this paper, as well as that reported for SAR11, was on the order of 40 h, which is fourfold less than the generation times of typical colony-forming opportunistic marine γ-proteobacteria (22). Furthermore, oligotrophic bacterioplankton appear to be small. Our isolates were in the same size category as SAR11 (length, ≤1 μm) (23). The advantage of being small could be that the cells are less susceptible to grazing (4). Interestingly, these small oligotrophic bacteria appear to have a highly efficient nutrient uptake mechanism. This was concluded by Zubkov et al. (M. V. Zubkov, I. J. Allen, and B. M. Fuchs, unpublished data), who measured the amino acid uptake in different size fractions sorted by flow cytometry. These traits allow oligotrophic bacteria to be important in the oceanic carbon cycle.

It is not known if these cells are motile. Mitchell et al. have argued that although small cells pay a high energetic price, high-speed motility is necessary in the marine environment (16, 17). During our investigation we were not able to observe rapid movement of the isolates. Instead, a wriggling motility difficult to distinguish from Brownian movement was observed. However, for a slowly growing cell, slow dispersal through Brownian movement may be enough to prevent aggregation. Thus, on the artificial substrate on an agar surface, this dispersal would result in failure to form colonies unless sensing mechanisms promote aggregation (21, 28). Gram et al. (11) described a scenario in which quorum sensing promotes aggregation on marine snow. However, cells lacking such behavior can be made to aggregate if they are prevented from dispersing. This was the case in our experiment in which the isolates were grown immersed in the agar (Fig. 2).

The taxonomic affiliation of oligotrophic bacteria also remains relatively vague. Acinas et al. (1) compared clone libraries from community DNA obtained from the free-living and attached fractions of bacterioplankton separated by filtration. In their analysis, samples of attached bacteria were characterized by low diversity and consisted mainly of well-known colony-forming γ-proteobacteria. On the other hand, the free-living community showed a predominance of mainly uncultured clones belonging to the α-proteobacteria, including a high abundance of SAR11 (18). However, among our oligotrophic isolates a wide variety of bacterial taxa, including γ-proteobacteria, were present (Table 2).

With these observations in mind it is tempting to speculate about the ecological advantage of the life strategy of slowly growing, non-colony-forming bacteria. Our isolates and the newly isolated SAR11 strain Pelagibacter ubique HTCC1062 (23) represent a group of oligotrophic bacteria that have been portrayed as the most successful organisms on Earth (18). We suggest that the inability to form colonies or biofilms is part of a K life strategy that oligotrophic bacterioplankton have adopted. During extended periods of time much of the surface ocean can be viewed as a poor source of utilizable organic matter (8). This situation is interrupted by occasional events when substrates become plentiful, such as after the collapse of algal blooms. However, in the periods when the levels of substrates are low, bacterial populations hover near the carrying capacity in a stable environment. Under these conditions it is reasonable to assume that there is a premium on the ability to successfully compete for resources with other members of the same species, and thus, colony formation should be nonadaptive.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Science Council (grant 621-2001-2814) and by the natural science faculty of Kalmar University. We are grateful for the use of laboratory and sampling facilities at Kristineberg Marine Research Station.

Ulla Li Zweifel kindly introduced us to the use of DAPI-stained seawater water agar slides. The comments of two anonymous reviewers were very helpful when the manuscript was revised.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acinas, S. G., J. Anton, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 1999. Diversity of free-living and attached bacteria in offshore western Mediterranean waters as depicted by analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:514-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammerman, J. W., J. A. Fuhrman, Å. Hagström, and F. Azam. 1984. Bacterioplankton growth in seawater. I. Growth kinetics and cellular characteristics in seawater cultures. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 18:31-39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson, A., U. Larsson, and Å. Hagström. 1986. Size-selective grazing by a microflagellate on pelagic bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 33:51-57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azam, F. 1998. Microbial control of oceanic carbon flux: the plot thickens. Science 280:694-696. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Button, D. K., F. Schut, P. Quang, R. Martin, and B. R. Robertson. 1993. Viability and isolation of marine bacteria by dilution culture: theory, procedures, and initial results. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:881-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connon, S. A., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. High-throughput methods for culturing microorganisms in very-low-nutrient media yield diverse new marine isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3878-3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducklow, H. 2000. Bacterial production and biomass in the oceans, p. 85-120. In D. E. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the oceans. Wiley-Liss, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Eberl, L., S. Molin, and M. Givskov. 1999. Surface motility of Serratina liquefaciens MG1. J. Bacteriol. 181:1703-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannoni, S. J. 1991. The polymerase chain reaction, p. 177-201. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Sequencing and hybridization techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 11.Gram, L., H.-P. Grossart, A. Schlingloff, and Kiørboe. 2002. Possible quorum sensing in marine snow bacteria: production of acetylate homoserine lactones by Roseobacter strains isolated from marine snow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4111-4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagström, Å., J. W. Ammerman, S. Henrichs, and F. Azam. 1984. Bacterioplankton growth in seawater. 2. Organic matter utilization during steady-state growth in seawater cultures. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 18:41-48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jannasch, H. W., and G. E. Jones. 1959. Bacteria populations in sea water as determined by different methods of enumeration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 4:128-139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch, A. L. 1997. Microbial physiology and ecology of slow growth. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:305-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane, D. J., B. Pace, G. J. Olsen, D. A. Stahl, M. L. Sogin, and N. R. Pace. 1985. Rapid determination of 16S rRNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 82:6955-6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell, J. G. 1991. The influence of cell size on marine bacterial motility and energetics. Microb. Ecol. 22:227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell, J. G., L. Pearson, S. Dillon, and K. Kantalis. 1995. Natural assemblages of marine bacteria exhibiting high-speed motility and large accelerations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4436-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris, R. M., M. S. Rappe, S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, W. A. Siebold, C. A. Carlson, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. SAR11 clade dominates ocean surface bacterioplankton communities. Nature 420:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyström, T. 1998. To be or not to be: the ultimate decision of the growth arrested bacterial cell. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:283-290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver, J. D. 1993. Formation of viable but nonculturable cells, p. 239-272. In S. Kjelleberg (ed.), Starvation in bacteria. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 21.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter, K. G., and Y. S. Feig. 1980. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25:943-948. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rappe, M. S., S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 418:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehnstam, A.-S., S. Bäckman, D. C. Smith, F. Azam, and Å. Hagström. 1993. Blooms of sequence-specific culturable bacteria in the sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 102:161-166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro, J. A. 1998. Thinking about bacterial populations as multicellular organisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:81-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevenson, L. H. 1978. A case for bacterial dormancy in aquatic systems. Microb. Ecol. 4:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki, M. T., C. M. Preston, F. P. Chavez, and E. F. Delong. 2001. Quantitative mapping of bacterioplankton population in seawater: field test across an upwelling plume in Monterey Bay. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 24:117-127. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winans, S. C., and B. L. Bassler. 2002. Mob psychology. J Bacteriol. 184:873-883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ZoBell, C. E. 1946. Marine microbiology: a monograph on hydrobacteriology. Cronica Botanica Co., Waltham, Mass.