Abstract

Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by branchial arch anomalies, hearing loss and renal dysmorphology. Although haploinsufficiency of EYA1 and SIX1 are known to cause BOR, copy number variation analysis has only been performed on a limited number of BOR patients. In this study, we used high-resolution array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) on 32 BOR probands negative for coding-sequence and splice-site mutations in known BOR-causing genes to identify potential disease-causing genomic rearrangements. Of the >1,000 rare and novel copy number variants (CNVs) we identified, four were heterozygous deletions of EYA1 and several downstream genes that had nearly identical breakpoints associated with retroviral sequence blocks, suggesting that non-allelic homologous recombination seeded by this recombination hotspot is important in the pathogenesis of BOR. A different heterozygous deletion removing the last exon of EYA1 was identified in an additional proband. Thus in total 5 probands (14%) had deletions of all or part of EYA1. Using a novel disease-gene prioritization strategy that includes network analysis of genes associated with other deletions suggests that SHARPIN (Sipl1), FGF3 and the HOXA gene cluster may contribute to the pathogenesis of BOR.

Keywords: array CGH, EYA1, birth defects, Branchio-oto-renal syndrome, copy number variation

INTRODUCTION

Branchio-otic (BO) syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by branchial cleft cysts, auricular or external auditory canal abnormalities, preauricular pits and hearing loss. Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome is diagnosed when BO is accompanied by malformations of the kidney or urinary tract, which range from mild hypoplasia to complete absence of one or both kidneys (Fraser et al. 1978; Matsunaga et al. 2007; Ruf et al. 2004). Multiple studies have shown that BOR is incompletely penetrant with variable expressivity, consistent with wide phenotypic variability between and within families. The most common manifestation is hearing loss, which can be conductive, sensorineural, or mixed (Hone and Smith 2001). Some studies estimate that BO/BOR has a prevalence of 2% amongst profoundly deaf children (Fraser et al. 1980).

BOR is genetically heterogeneous, although mutations in EYA1 are most commonly identified and segregate with the BOR phenotype in about 40% of families (Abdelhak et al. 1997a; Abdelhak et al. 1997b; Chang et al. 2004; Krug et al. 2011; Matsunaga et al. 2007; Orten et al. 2008). Causative variants include point mutations as well as large and small deletions (Abdelhak et al. 1997b; Ni et al. 1994; Vincent et al. 1997). EYA1 encodes a transcriptional regulator (Abdelhak et al. 1997b) and mice heterozygous for the targeted deletion of this gene have renal abnormalities and a conductive hearing loss similar to the human phenotype. Eya1 homozygous null mice lack ears and kidneys (Xu et al. 1999b).

Mutations in both SIX1 and SIX5 are also associated with BOR syndrome. SIX1, the human homolog of Drosophila sine oculis gene, encodes a DNA binding protein that associates with EYA1 (Ruf et al. 2004). Most mutations identified in SIX1 are missense mutations but small deletions have also been reported in patients with BOR syndrome (Kochhar et al. 2008; Ruf et al. 2003; Ruf et al. 2004; Sanggaard et al. 2007). The role of SIX5 in BOR is less clear. Although a few missense mutations in SIX5 have been reported in patients with BOR syndrome (Hoskins et al. 2007; Krug et al. 2011; Ruf et al. 2004), the role of SIX5 variants in the pathophysiology of BOR has been questioned (Krug et al. 2011).

The purpose of this study was to assess the role of copy number variation in the BOR phenotype by performing high-resolution array-based Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) on a cohort of 32 BOR probands negative for coding-sequence and splice-site mutations in the known BOR-causing genes. We identified a recombination hotspot that is responsible for deletion of the EYA1 locus (in addition to several other genes) in four unrelated probands, as well as a second deletion that removes a portion of EYA1 in a fifth proband, further substantiating involvement of this locus in BOR. Additionally, using a novel disease-gene prioritization strategy that includes pathway analysis of genes deleted in the remaining probands, we implicate SHARPIN (Sipl1), FGF3, and the HOXA gene cluster as candidate genes that may contribute to the BOR syndrome phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples selection for array-based CGH

Patients were diagnosed with BOR syndrome based on their clinical phenotype (Chang et al. 2004; Chen et al. 1995). Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood in patients providing informed consent. The isolated genomic DNA was quantified and assessed for quality using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific; Wilmington, DE) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The coding regions and splice sites in EYA1, SIX1 and SIX5 were analyzed by Sanger sequencing. Patients negative for this mutation analysis were eligible for this study. All procedures were approved by the University of Iowa human research internal review board (IRB).

Array-based CGH and CNV detection and Interpretation

Thirty-five patients were included in this aCGH study but only 32 passed all quality control parameters (see Supplementary Material). Labeling of the patient samples and a normal male reference was performed using Cy3- and Cy5-labeled random nonamers (TriLink Biotechnologies; San Diego, CA), respectively. The labeled DNAs were hybridized to a NimbleGen human CGH 2.1 million feature whole-genome tiled microarray (v2.0D), and the arrays were processed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Microarrays underwent stripping and reuse as described previously (Bassuk et al. 2013) and the reuse strategy was further validated (Supplementary Material – Array Reuse Protocol and Noninferiority Testing and Figure S1). The DEVA software tool (version 1.0; Roche NimbleGen) was used for feature extraction, calculation of log2 ratio values, and segmentation using the segMNT algorithm. Additional CNV calling algorithms and data interpretation were performed using the Nexus Copy Number Discovery Edition software tool (version 5.1, BioDiscovery; El Segundo, CA) and the FASST2 and RANK algorithms supplied with the Nexus software suite. All array data were quality controlled using the experimental metrics calculated by DEVA and Nexus Copy Number (Supplementary Material – Quality Control Analysis of Microarray Data). Array data not meeting quality control thresholds were excluded from further analysis.

CNV pathogenicity determination

CNVs were called with three algorithms (SegMNT, FASST2 and RANK) using permissive settings (Supplementary Material – Copy Number Variation Calling Algorithms and Software) and those regions that exhibited consistent copy number variation across all three algorithms comprised our final CNVR set. This call set met previously determined biologic criteria that included the appropriate ratio of deleted vs. duplicated sequence content, exon/intron/intergenic content, and novel vs. polymorphic regions (Supplementary Material – Biological Assessment of Different Calling Algorithms). All CNVRs were compared against clinically relevant databases and published CNV datasets to determine likely pathogenicity. Data sources included the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV; http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/), the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute’s DECIPHER database (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/), the database curated by the International Standards for Cytogenetic Arrays (ISCA) consortium (https://www.iscaconsortium.org/), our internal clinical array CGH database, and the CNV datasets published by Conrad and Cooper and colleagues ((Conrad et al. 2010; Cooper et al. 2011); Supplementary Material – Interpretation of CNVRs for Potential Pathogenicity). CNVRs that were not classified as benign and contained at least one reviewed or validated RefSeq gene were classified as either “Abnormal” or “Variants of Uncertain Significance” (VUS). “Abnormal” CNVRs included known pathogenic lesions (such as 17q12 or 22q11.2 deletion) and novel variants of >1Mb in size. VUS were non-benign CNVRs that did not meet criteria for “Abnormal”. CNVRs were considered “Diagnostic” if they were either “Abnormal” or VUSs >100Kb in size.

Gene prioritization with novel CNVRs in the BOR cohort

Three methods were used to prioritize potential BOR-associated genes in large (>1Mb), novel CNVRs. The first method, “overlap” analysis, consisted of querying clinical databases of CNVs (DECIPHER, ISCA, our own clinical database a recent publication on CNVs and developmental delay (Cooper et al. 2011)), for CNVs that overlapped the novel deletion interval. Potential overlapping CNVs were excluded if they were known copy number polymorphisms. The region of “moderate overlap” was chosen by selecting the interval that contained not only the most overlapping segments of CNVs but an extended region that included the next most overlapping segments on either side (see Supplementary Material – Gene Prioritization within Novel CNVRs and Figure S5 for example). Genes present in the region of moderate overlap were ranked based on the relative overlap of other clinically relevant CNVs. The second method of prioritization was predicted haploinsufficiency. Genes within novel deletion intervals were ranked according to their haploinsufficiency score (Huang et al. 2010). The third method involved creating and examining protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. To guide this analysis, we used the published C. elegans interactome (Li et al. 2004) in relation to the orthologous human genes to create a hypothetical human EYA1 interactome. Three tiers of potential human EYA1 interacting partners were created (Table S7; “good candidates”=yellow, “possible candidates”=orange, and “poor candidates”=red) by determining whether human, mouse, or Xenopus orthologs existed. Peptide BLAST scores were catalogued for each organism, with proteins classified as “good” candidates if they had blast hits/known orthologs in all three vertebrate model organisms. Exceptions were made if orthologs were not present in all three model organisms, but expression data placed the partners together. “Possible” candidates had known orthologs in either 1 of 3 or 2 of 3 of the model organisms. Occasionally, all three model organisms had orthologs but the protein was unlikely to be involved because of its function (for example afd-1, which has been associated with a different disease process unlikely to be related to BOR). In these cases, BLAST scores were included for future potential testing. “Poor” candidates had no known ortholog in the three model organisms, and were given the lowest priority.

After prioritization, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was used to create PPI networks by interfacing genes from the C. elegans-guided human EYA1 interactome with genes present within the novel deletion intervals (Supplementary Material – Gene Prioritization within Novel CNVRs for example and IPA settings). Genes (or connecting genes) present in both lists were used to condense the interconnected PPI networks into a succinct system of relationships that involved known human BOR-causing genes, human orthologous genes from the C. elegans-guided human EYA1 interactome, and genes from the novel deletion interval (Figures 2, S6, and S7). The result was a concise PPI network for each novel deletion interval that elucidated the most likely BOR-causing genes based on known protein-protein relationships that involve EYA1 or likely interaction partners.

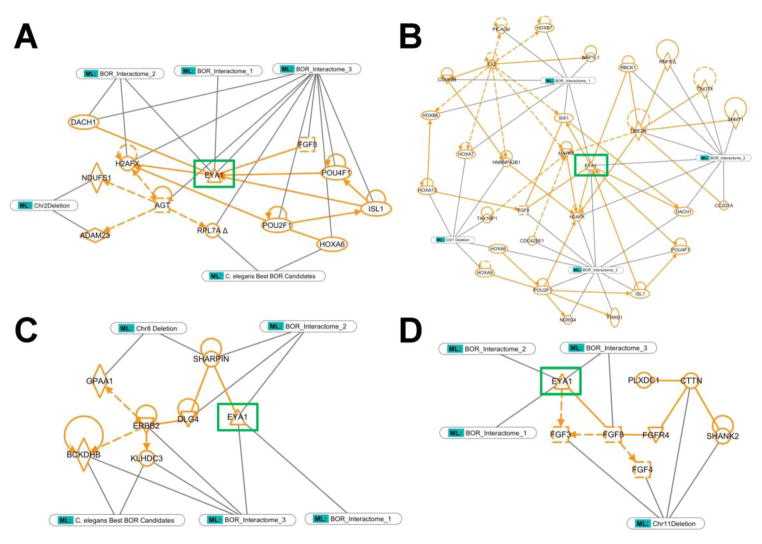

Figure 2. Individual concise protein-protein interaction networks generated for each large, novel deletion found in the BOR cohort using a C. elegens EYA1 interactome informed IPA analysis.

IPA core analysis of the human orthologs of the good C. elegans EYA1 interacting candidates produced three dominant PPI networks (BOR Interactomes 1, 2, and 3). IPA core analysis of the genes contained within the large, novel deletions often produced just one dominant network. Molecules present in both sets of PPI networks were identified and used to intersect and condense the separate PPI networks into a succinct system of relationships that involved known BOR-causing genes (EYA1, SIX1), genes from the C. elegans-guided human EYA1 interactome (BOR Interactomes), and genes from the novel deletion intervals. Genes present in the BOR-related deletion (A: Chr2 deletion, B: Chr7 deletion, C: Chr8 deletion, D: Chr11 deletion) are indicated. All network connections and molecules are labeled in orange and all identification tags and lines are in grey/green. The “C. elegans Best BOR Candidates” tag refers to those molecules that were explicitly contained in the good C. elegans EYA1 interacting candidate list and not only a product of IPA network generation. EYA1 is highlighted with a green box across all pathways for orientation. Dotted lines reflect indirect relationships and solid lines indicate direct relationships.

The results of these three methods were integrated to create a refined list of candidate disease genes for BOR that are present within these large, novel deletions (Table S9). All gene enrichment calculations were performed using IPA and were subjected to a Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction.

Long-range PCR and break point characterization

Breakpoint characterization of EYA1-including CNVs was completed by LR–PCR using the TAKARA PCR System kit (TaKaRa LA Taq, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Primer pairs covering putative break points for each deletion were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). PCR products were resolved on a 1.0% agarose gel, visualized by ethidium bromide staining, and purified using a PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified PCR products were bidirectionally Sanger sequenced according to standard protocols. Approximate genomic sequence coordinates for each deletion breakpoint were estimated based on breakpoint assessments of segMNT plots generated by Roche NimbleScan CGH software. Analysis of the sequencing results was performed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI). Breakpoint regions were analyzed by RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org) for interspersed repeat and low complexity DNA sequences, and the LALIGN tool of the Swiss EMBnet (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGN_form.html) to compare interspersed repeat sequences.

RESULTS

aCGH analysis of BOR probands

Thirty-two of 35 BOR proband samples passed quality control requirements and were placed in the analysis pipeline using an array reuse strategy (see Methods and Figure S1). We identified approximately 5,000 high quality CNVRs (a minimum of three probes was required to call a CNV using any of the aforementioned algorithms); however, we only considered for further analysis those regions called variable by three different algorithms (see Methods). In total, we identified more deleted than amplified genomic content, but nonetheless identified a high number of small (<10kb) amplifications (Figure S2 and Table S1). Approximately 75% of CNVRs had complete overlap with published copy number polymorphic loci in HapMap populations (Conrad et al. 2010) (Figure S3 and Table S2) with ~53% involving at least one exon of one reviewed, provisional or hypothetical RefSeq protein-coding gene (Figure S4). In total, we identified 17 diagnostic lesions, including 5 in the region including EYA1 gene and 12 in non-EYA1 associated regions. Table 1 summarizes these diagnostic CNVRs.

Table 1.

Diagnostic CNVRs identified in the BOR cohort.

| Case Number | Diagnostic Lesion |

|---|---|

| 2310 | chr16:29,643,062-30,109,349 Deletion (Autism susceptibility locus 16p11.2 – Well Known Lesion) |

| 2330 | chr22:17,403,706-19,790,657 Deletion (22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome – DiGeorge, VCFS, Shprintzen, and conotruncal anamaly face syndrome) |

| 2740 | chr7:22,954,310-34,757,630 Deletion (7p15.1p14.3 – NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving over 150 genes) |

| 20120 | chr16:29,558,172-30,109,349 Duplication (Autism susceptibility locus 16p11.2 – Well Known Lesion) |

| 20470 | chr7:2,928,572-3,283,586 Duplication (7p22.2 NOVEL VUCS CNV involving CARD11 gene) |

| 20610 | chr8:72,268,914-72,273,977 Deletion (8q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving the 5′ end of the EYA1 gene) |

| 20660 | chr7:145,980,898-146,599,435 Deletion (7q35 NOVEL VUCS CNV involving exons 2–8 of the CNTNAP2 gene) |

| 20960 | chr8:70,053,668-72,748,108 Deletion (8q13.3q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving EYA1 gene amongst many others) |

| 21230 | chr8:70,499,065-72,747,518 Deletion (8q13.3q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving EYA1 gene amongst many others) |

| 21460 | chr2:204,689,752-211,551,656 Deletion (2q33.3q34 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving over 50 genes |

| 21490 | chr16:29,559,931-30,120,701 Duplication (Autism susceptibility locus 16p11.2 - Well Known Lesion) |

| 21790 | chr22:17,402,877-19,789,499 Duplication (22q11.2 Duplication Syndrome – Well Known Duplication) AND chr11:69,294,008-70,326,320 Deletion (11q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving over 10 genes) |

| 22040 | chrX:22,104,624-22,467,300 Duplication (Xp22.11 NOVEL VUCS CNV involving two genes PHEX and ZNF645) |

| 22050 | chr17:26,126,973-26,358,711 Duplication (17q11.2 NOVEL VUCS CNV involving 5 genes including RNF135) |

| 516570 | chr8:142,429,070-145,504,109 Deletion (8q24.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving over 80 genes) |

| 518240 | chr8:70,053,668-72,748,108 Deletion (8q13.3q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving EYA1 gene amongst many others) |

| CDS-2893 | chr8:70,053,668-72,748,108 Deletion (8q13.3q13.3 NOVEL ABNORMAL CNV involving EYA1 gene amongst many others) |

Breakpoint Characterization in EYA1-Associated CNVs

Amongst the list of CNVs we identified, we found heterozygous deletions in five probands that removed all or part of EYA1.

Deletion type 1 - microdeletion of the 3′ end of EYA1

A microdeletion towards the 3′ end of EYA1 was identified in patient 20610. aCGH mapped the distal breakpoint between 72,111,364 and 72,113,545 bp and the proximal breakpoint between 72,105,711 and 72,106,360 bp. Long-Range PCR (LR-PCR) and Sanger sequencing defined the deleted bases as hg19: 72,106,185-72,111,858 bp, making the deletion precisely 5,673 bp. The deletion includes part of intron 17 of EYA1, exon 18 and the entire 3′ UTR.

Deletion type 2 - large contiguous gene deletion including EYA1

Four patients had a nearly identical large genomic deletion that includes EYA1 and 9 neighboring genes (shown in Figure 1; these include SULF1, SLCO5A1, PRDM14, NCOA2, TRAM1, LACTB2, XKR9, and two non-coding RNAs). Analysis of the aCGH data revealed that the distal breakpoint likely maps within a few kb of chr8:72,587,445, hg19, whereas the proximal breakpoint likely maps within a few kb of chr8:69,899,445, hg19, predicting a ~2.7 Mb deletion. We included three of the four DNA samples in serial LR-PCR and narrowed the junction fragment to an amplicon of 2.9 kb (Tables S3). Analysis of the break point intervals using repeatmasker showed that the distal break point contains 87% masked bases while the proximal break point has 99.5% masked bases. LALIGN analysis showed that these two Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs) have >80% sequence identity. Both the distal and proximal deletion breakpoints are flanked by the LTR-ERV_class I elements, with 89% homology and situated in the same orientation (Table 2). We used the significance testing for aberrant copy number (STAC) algorithm to show that this region was concordantly aberrant across BOR probands more than would be expected by chance (p = 0.009). Thus, four of 32 patients contained a common genomic rearrangement likely mediated by non-allelic homologous recombination.

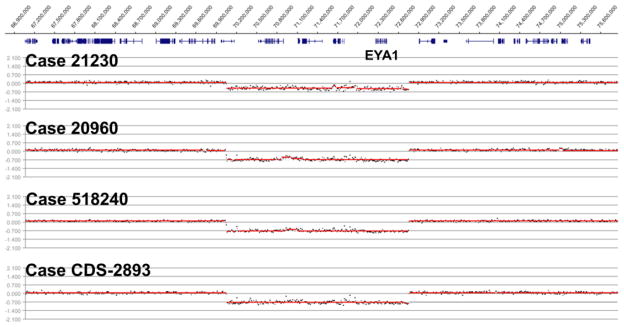

Figure 1. Identification of a recurrent EYA1 deletion.

Array-based CGH results visualized in the Roche NimbleGen SignalMap genome browser generated with default segMNT algorithm settings (12,000 bp averaging). Probands (cases) are indicated above each segmentation profile. Genes (collapsed) are indicated above segmentation data; EYA1 is labeled. Genomic locations are indicated at the top of the figure (hg18 genome build).

Table 2.

Interspersed elements found in both proximal and distal breakpoints by analysis of 4 kb surrounding each breakpoint.

| Deletion type | Type of element | # of elements | Length occupied (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Large contiguous gene deletion containing EYA1 | Proximal IEs | LTR-ERV_class I | 2 | 3986 |

|

| ||||

| Distal IEs | LTR-ERV_class I | 1 | 2893 | |

| LINE1 | 3 | 1079 | ||

|

| ||||

| Microdeletion at 3′ end of EYA1 | Proximal IEs | MIRs | 2 | 192 |

| LINE2 | 2 | 591 | ||

| LTR-ERV_class I | 1 | 119 | ||

| DNA elements | 2 | 521 | ||

|

| ||||

| Distal IEs | MIRs | 1 | 105 | |

| LINE1 | 1 | 38 | ||

IEs: Interspersed Elements

Non-EYA1 Deletions and Duplications

In addition to the multiple EYA1 deletions, we identified several novel microdeletions and amplifications in probands who did not have an EYA1 lesion. In total, 12 other BOR probands had a “diagnostic” lesion by aCGH (see Methods and Table 1). In four of these probands, the novel deletions were >1Mb and involved chromosomes 2q33.3q34 (6.9Mb), 7p15.1p14.3 (11.8Mb), 8q24.3 (3.1Mb), and 11q13.3 (1.0Mb). Other significant lesions involved the well-known autism susceptibility locus on 16p11.2 (two duplications and one deletion in three separate individuals), and the DiGeorge/Velocardiofacial Syndrome locus on 22q11.2 (one deletion in one patient and one duplication found in the same patient as the 11q13.3 deletion). The four remaining diagnostic lesions included a 630Kb deletion of 7q35 involving exons 2–8 of the CNTNAP2 gene (located in the known deafness locus DFNB13, with no gene identification yet). These non-EYA1 diagnostic lesions have been summarized in Table S4. In addition to these diagnostic lesions we found 52 rare and novel CNVRs that were of interest but <100Kb in size (Table S4). Available clinical data on all patients with likely pathogenic CNVs (either EYA1- or non EYA1-associated) are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relevant clinical data of the 17 cases with likely pathological CNVs.

| Patient ID | Major BOR Criteria x ≥ 2 | Minor BOR Criteria | Other clinical abnormalities related to the affected organs in BOR syndrome | Additional abnormalities (non-relevant to BOR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ear | Face/Mouth | Branchial | |||||

| 1 | 21230 | Preauricular pits, hydronephrosis, branchial fistulae | Pinnae deformity (cup ear) | Microtia, middle ear anomaly (absent right external auditory canal) | Small mouth | Branchial Tag | |

| 2 | 20960-1 | Hearing loss, hypoplasia, branchial fistulae | Pinnae deformity (cup ear) | Abnormal clavicles | |||

| 3 | 518240 | Hearing loss, preauricular pits, branchial fistulae, reflux, hydronephrosis | Preauricular tags | Middle ear anomalies (external auditory stenosis) | |||

| 4 | CDS-2893 | Unavailable clinical data | Unavailable clinical data | Unavailable clinical data | Unavailable clinical data | Unavailable clinical data | Unavailable clinical data |

| 5 | 20610 | Preauricular tags and pits, bil. branchial cyst, right kidney agenesis | Pinnea deformity (ear cup) | Lacrimal duct stenosis, hair patch on neck | |||

| 6 | 2310 | Hearing loss, hydronephrosis, kidney reflux | Microtia, external auditory stenosis | ||||

| 7 | 20120 | Preauricular pits, renal pelviectasis | Branchial Tags | ||||

| 8 | 21490 | Hearing loss, hydronephrosis | Preauricular tags | Microtia, middle ear abnormalities (atresia of left external auditory canal) | |||

| 9 | 2740 | Hearing loss, branchial fistulae, hypoplasia, small kidneys | Branchial cleft cyst | Cardiac defects, Brachydactyly, Hydrometrocolpos | |||

| 10 | 516570 | Preauricular pits, assymetry of kidneys | Pinnae deformity (cup ear) | Branchial Tag | Cardiac defect (TOF) | ||

| 11 | 21790 | tragus abnormalities, hypoplastic ear | |||||

| 12 | 2330 | Hearing loss, Kidney agenesis | Facial assymetry | Inner ear abnormalities (bilateral Mondini Defect, and enlarged vestibular aqueduct) | |||

| 13 | 20470 | Hearing loss, preauricular pits, duplex collecting system | Pinnae deformity (cup ear) | Short 5th finger on right hand, mild clinodactyly of 5th digit bilaterally | |||

| 14 | 20660 | Hearing loss, multicystic kidneys, ureteral malformation | |||||

| 15 | 21460 | branchial fistula, hypoplasia | Pre-uvular groove | 5th finger and toe hypoplasia, devel. delay, learning difficulties | |||

| 16 | 22040 | Hearing loss, preauricular pits, horseshoe kidney | Preauricular tags, retrognathia | ||||

| 17 | 22050 | hearing loss, right renal malrotation, left hydronephrosis | Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) | ||||

Gene Prioritization in Novel CNVs

To determine which genes within the larger (>1Mb) novel deletions are likely contributors to the BOR phenotype, we completed three separate yet complementary prioritization analyses of the genes within these intervals. The first analysis, termed “overlap” analysis (see Methods), was selected because phenotypic data are often lacking for many of the CNVs reported within clinical databases. Thus it is possible that these CNVs may cause a phenotype similar to BOR or may involve one of the primary organ systems affected in BOR. From this analysis we identified genes that were present in a region of ‘moderate overlap’ across multiple clinically relevant CNVs (see Methods and Figure S5), hypothesizing that genes within this region are more likely to cause a human disease phenotype (Table S5). Our second analysis ranked genes within deletions according to the likelihood of haploinsufficiency (Huang et al. 2010) (Table S6). The third analysis created and examined protein-protein interaction networks. To guide this analysis, we utilized the C. elegans interactome and orthologous human genes to create a hypothetical EYA1 interactome (Table S7). We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to create two sets of PPI networks using: 1) genes from both the C. elegans-guided human EYA1 interactome (Figure S6), and, 2) those genes within the novel deletion intervals. Genes present in both sets of PPI networks were identified and used to intersect and condense the separate PPI networks into a succinct system of relationships that involved known BOR-causing genes, genes from the C. elegans-guided human EYA1 interactome, and genes from the novel deletion intervals (see Methods; Figure S7). The result was a concise PPI network for each novel deletion interval (Figure 2 and Table S8). These separate networks were then combined into one large network (see Methods and Figure 3). Notably, this network is significantly enriched for genes involved in both morphogenesis of the metanephric bud (p = 0.001) and development of the inner ear (p = 0.001; see Methods). The results of these analyses also yielded a set of high quality candidate disease genes for BOR (Table 4; see Table S9 for a more expanded view of potential candidates).

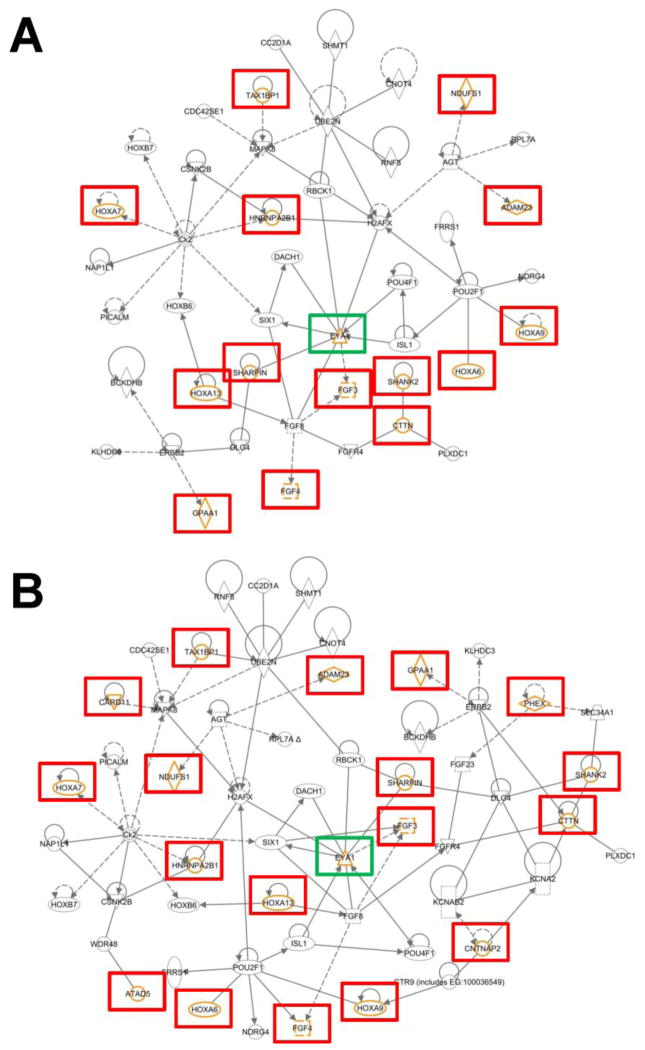

Figure 3. C. elegans and CNV-aided human EYA1 interactome.

The smaller network shown in A is composed of molecules that are known BOR pathogenic genes, candidate BOR genes from the C. elegans EYA1 interactome, and genes (highlighted with orange symbols and red boxes) present in the four large, novel deletions found within the BOR cohort examined in this study. The larger network shown in B is a more comprehensive network that also includes genes found within other diagnostic CNVRs and variants of unknown significance (also highlighted with orange symbols and red or green boxes). EYA1 is highlighted with a green box for orientation. Dotted lines reflect indirect relationships and solid lines indicate direct relationships.

Table 4.

Candidate BOR Genes Ascertained from Multiple Analyses of Novel Diagnostic CNVRs.

| Deletion | Gene Symbol | Haplo- insufficiency Score | Overlap Score | Pathway Score | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr 2 | KLF7 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| ADAM23 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | |

| IDH1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | |

| NDUFS1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| PARD3B | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| Chr 7 | HNRNPA2B1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 12 |

| HOXA13 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 | |

| HOXA7 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 | |

| HOXA9 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 11 | |

|

| |||||

| Chr 8 | EEF1D | 5 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| SHARPIN | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | |

| BOP1 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| EXOSC4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| SCRIB | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

|

| |||||

| Chr 11 | FGF3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| FGF4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 13 | |

| CTTN | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |

| SHANK2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | |

DISCUSSION

Here we use copy number variation analysis on a cohort of BOR cases to identify five probands (out of a total of 32) with a complete or partial EYA1 deletion, further demonstrating that EYA1 is a key player in this disorder. To identify other potential candidates, we used interactome data to perform network analysis of CNV-associated genes in order to identify pathways enriched in our gene dataset. Notably, we identified two classes of significantly enriched genes which are involved in development of the organ systems directly affected by BOR (morphogenesis of the metanephric bud and development of the inner ear) and identified SHARPIN, FGF3 and the HOXA gene cluster as potential BOR candidate genes.

EYA1-associated deletions are a frequent cause of BOR

Four of the 32 unrelated BOR cases contained a common ~2.7 Mbp deletion involving EYA1, with the breakpoints residing in LTR elements of the ERV1 retrovirus family. Given the frequency of this deletion (12.5% of the total number of cases), it is likely that this rearrangement is a relatively common event leading to BOR in patients negative for EYA1 coding region and splice-site mutations by Sanger sequencing. Along these lines, Sanchez-Valle and colleagues (Sanchez-Valle et al. 2010) identified the same deletion in one of three DNA samples from cases where high resolution CGH was performed, providing additional evidence that this rearrangement is an important cause of BOR. Both retroviral elements associated with the rearrangement breakpoints are greater than 3 kb in length and the element nearest to EYA1 is in close proximity (less than 5 Kb) to a second ERV1 family LTR element.

In addition to the 4 large EYA1-associated deletions, we identified a smaller deletion that removed the last exon of EYA1, and the 3′ UTR and polyadenylation signal. Thus, the resulting message is likely destabilized and quickly degraded. In total, 5 of 32 probands (14%) had EYA1-associated deletions. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that additional probands might harbor regulatory mutations in the EYA1 locus, it is likely that other genes contribute to the BOR phenotype (see below). In addition, we note that we failed to identify deletions of either of the other 2 known BOR-causing genes, SIX1 or SIX5, in any of our probands.

SHARPIN, FGF3 and the HOXA gene cluster are novel BOR candidate genes

The genes we identified as possible candidates for causing and/or influencing the BOR phenotype are high probability candidates because they rose to the top of the three-tiered prioritization analysis and also have independent lines of evidence to support a possible role in a BOR phenotype. SHARPIN, present in the novel deletion on chromosome 8, has been shown to be a novel Eya1 binding partner in mice and plays a critical role in craniofacial development (Landgraf et al. 2010). Specifically, morpholino-mediated knockdown of the zebrafish ortholog of SHARPIN produces a BOR syndrome-like phenotype and shows that Sipl1 directs the development of several organs including the ears and branchial arches. Sipl1 is co-expressed with Eya1 in several organs during murine and zebrafish embryogenesis and at the molecular level, acts as cofactor for the Eya-Six complex. The phenotype in the patient 516570 carrying this large chromosome 8q24.3 deletion included cardiac defects (TOF) in addition to hearing loss, pinnae deformity (cup ear), preauricular pits and asymmetric kidneys.

The 11.8 Mbp large deletion of 7p15.1-14.3 found in the patient 2740 removes the genes of the HOXA gene cluster, which themselves are good BOR candidates since they are known to be involved in craniofacial development (VieilleGrosjean et al. 1997). Whereas HOXA2 did not score very high compared to other members of the HOXA cluster in our prioritization analysis, it plays a critical role in development of the middle and external ear (Alasti et al. 2008; O’Gorman 2005; Tischfield et al. 2005; VieilleGrosjean et al. 1997) and mutation of its highly conserved homeodomain has been causally implicated in autosomal recessive bilateral microtia, mixed symmetrical severe-to-profound hearing impairment and cleft palate (Alasti et al. 2008). Of the other HOXA family members, a homozygous mutation of HOXA1 has been reported to disrupt the inner and outer ear and cause facial, brainstem and cardiac abnormalities (Tischfield et al. 2005). HOXA13, which ranked high in our analysis, has been implicated in dominantly inherited hand-foot-genital syndrome (Goodman et al. 2000). The phenotype of patient 2740 carrying the deletion of 7p15.1-14.3 included cardiac defects, brachydactyly and hydrometrocolpos in addition to hearing loss, branchial fistulae, branchial cyst and small hypoplastic kidneys. We believe this patient likely represents a distinctive novel contiguous gene deletion syndrome.

Within the chromosome 11 deletion, FGF3 is a strong BOR-causing and/or modifying gene candidate because its murine ortholog has been shown to be required for inner ear patterning (Gregory-Evans et al. 2007; Leger and Brand 2002; Wright and Mansour 2003; Xu et al. 1999a), and mice harboring Fgf-3 mutations have inner ear defects (Mansour et al. 1993). In humans, microdeletions involving this locus are associated with oto-dental syndrome, a rare but severe autosomal dominant craniofacial abnormality that includes sensorineural hearing loss (Gregory-Evans et al. 2007).

Lastly, the chromosome 2 deletion provides for a few potential candidates, although these candidates are not as strong as those found in the other large, novel deletions.

Known susceptibility loci likely play a role in BOR

Unexpectedly, given our relatively small sample size, we observed a high incidence of variants involving known susceptibility loci, such as the autism susceptibility locus on 16p11.2 (two duplications, one deletion) and the DiGeorge/velo-cardiofacial syndrome locus on 22q11.2 (one duplication). Deletions and duplications of 16p11.2 have been associated with numerous phenotypes, including autism, schizophrenia, seizures, developmental delay, and obesity. Amongst neuropsychiatric disorders, deletions may be more commonly associated with autism and duplications with schizophrenia (McCarthy et al. 2009), though these relationships are not exclusive. The copy number variation at this locus could be either inherited or de novo, and the phenotype can vary across family members to the extent that not all individuals with the deletion or duplication have an identifiable phenotype. Several additional phenotypes have been associated with copy number variation at 16p11.2 including ones that involve the genitourinary organ system including Mullerian aplasia (Nik-Zainal et al. 2011), hypospadias (Tannour-Louet et al. 2010), and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) (Sampson et al. 2010). How or whether these variations influence the BOR phenotype is unclear, yet our results add further support to the heterogeneity in phenotype related to deletions/duplications at 16p11.2. Duplications of 22q11.2 represent the predicted reciprocal rearrangements to 22q11.2 deletions, and contain ~50 verified genes, including TBX1. They are most often inherited from an apparently unaffected parent, and the associated phenotype is variable, ranging from multiple defects to mild learning difficulties. Duplications of this locus share features with the more common deletion and include genitourinary abnormalities (Portnoi 2009). The incidence of urogenital abnormalities in the classic 22q deletion syndrome is well documented and can include renal agenesis, hydronephrosis, multicystic/dysplastic kidneys, duplicated kidney, horseshoe kidney, absent uterus, hypospadias, inguinal hernia, and cryptorchidism (McDonald-McGinn et al. 2005). We observed one 22q deletion (in patient 2330) and one 22q duplication (in patient 21790). The first patient’s phenotype also included Mondini dysplasia, making ATP6V1E1, SLC25A1 and SLC25A18 interesting candidates, and the patient with the 22q duplication also carried the chromosome 11 deletion (including FGF3), raising the possibility of a novel CNV-CNV interaction.

Summary

BOR syndrome is a very common form of syndromic hearing loss that additionally includes branchial arch and renal abnormalities. The majority of cases are caused by mutations in EYA1 (~40% of BOR cases: 80% point mutations and small indels, 20% large deletions) although SIX1 and SIX5 also make small contributions to the BOR phenotype. In this study, we identified 17 diagnostic CNV lesions in 32 BOR probands, including 5 in the region containing EYA1 and 12 in non-EYA1 associated regions. Deletion of all or part of EYA1 in 14% of our patients further supports the strong association of EYA1 with BOR.

Using a novel disease-gene prioritization strategy (integration of 3 methods) that includes pathway analysis of genes in the deleted interval regions relative to the 12 non-EYA1 diagnostic lesions, we have identified a set of strong candidate genes associated with the pathogenesis of BOR syndrome including SHARPIN (Sipl1), FGF3 and the HOXA cluster. Consistent with this hypothesis, in each case, mutation or knockdown of each of these genes has been shown to cause phenotypes similar to BOR in either humans or other model organisms (see above).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Hakeman and Jason Dierdorff for expert technical assistance. We also thank Rachel Brouillette for assistance in making figures. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01DE021071-01 to JRM) and start-up funds (to JRM).

Footnotes

ETHICAL STANDARDS

All experiments comply with current laws of the United States of America.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have conflicts of interest related to this work.

The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first three authors should be regarded as joint First Authors.

REFERENCE LIST

- Abdelhak S, Kalatzis V, Heilig R, Compain S, Samson D, Vincent C, Levi-Acobas F, Cruaud C, Le Merrer M, Mathieu M, Konig R, Vigneron J, Weissenbach J, Petit C, Weil D. Clustering of mutations responsible for branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome in the eyes absent homologous region (eyaHR) of EYA1. Human molecular genetics. 1997a;6:2247–55. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhak S, Kalatzis V, Heilig R, Compain S, Samson D, Vincent C, Weil D, Cruaud C, Sahly I, Leibovici M, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Francis M, Lacombe D, Vigneron J, Charachon R, Boven K, Bedbeder P, Van Regemorter N, Weissenbach J, Petit C. A human homologue of the Drosophila eyes absent gene underlies branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome and identifies a novel gene family. Nature genetics. 1997b;15:157–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasti F, Sadeghi A, Sanati MH, Farhadi M, Stollar E, Somers T, Van Camp G. A mutation in HOXA2 is responsible for autosomal-recessive microtia in an Iranian family. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;82:982–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk AG, Muthuswamy LB, Boland R, Smith TL, Hulstrand AM, Northrup H, Hakeman M, Dierdorff JM, Yung CK, Long A, Brouillette RB, Au KS, Gurnett C, Houston DW, Cornell RA, Manak JR. Copy number variation analysis implicates the cell polarity gene glypican 5 as a human spina bifida candidate gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1097–111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EH, Menezes M, Meyer NC, Cucci RA, Vervoort VS, Schwartz CE, Smith RJ. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: the mutation spectrum in EYA1 and its phenotypic consequences. Human mutation. 2004;23:582–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Francis M, Ni L, Cremers CWRJ, Kimberling WJ, Sato Y, Phelps PD, Bellman SC, Wagner MJ, Pembrey M, Smith RJH. Phenotypic Manifestations of Branchiootorenal Syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1995;58:365–370. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320580413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF, Pinto D, Redon R, Feuk L, Gokcumen O, Zhang Y, Aerts J, Andrews TD, Barnes C, Campbell P, Fitzgerald T, Hu M, Ihm CH, Kristiansson K, Macarthur DG, Macdonald JR, Onyiah I, Pang AW, Robson S, Stirrups K, Valsesia A, Walter K, Wei J, Tyler-Smith C, Carter NP, Lee C, Scherer SW, Hurles ME Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature. 2010;464:704–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM, Coe BP, Girirajan S, Rosenfeld JA, Vu TH, Baker C, Williams C, Stalker H, Hamid R, Hannig V, Abdel-Hamid H, Bader P, McCracken E, Niyazov D, Leppig K, Thiese H, Hummel M, Alexander N, Gorski J, Kussmann J, Shashi V, Johnson K, Rehder C, Ballif BC, Shaffer LG, Eichler EE. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2011;43:838–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser FC, Ling D, Clogg D, Nogrady B. Genetic aspects of the BOR syndrome--branchial fistulas, ear pits, hearing loss, and renal anomalies. American journal of medical genetics. 1978;2:241–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser FC, Sproule JR, Halal F. Frequency of the branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome in children with profound hearing loss. Am J Med Genet. 1980;7:341–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320070316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman FR, Bacchelli C, Brady AF, Brueton LA, Fryns JP, Mortlock DP, Innis JW, Holmes LB, Donnenfeld AE, Feingold M, Beemer FA, Hennekam RC, Scambler PJ. Novel HOXA13 mutations and the phenotypic spectrum of hand-foot-genital syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2000;67:197–202. doi: 10.1086/302961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Evans CY, Moosajee M, Hodges MD, Mackay DS, Game L, Vargesson N, Bloch-Zupan A, Ruschendorf F, Santos-Pinto L, Wackens G, Gregory-Evans K. SNP genome scanning localizes oto-dental syndrome to chromosome 11q13 and microdeletions at this locus implicate FGF3 in dental and inner-ear disease and FADD in ocular coloboma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16:2482–2493. doi: 10.1093/Hmg/Ddm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hone SW, Smith RJ. Genetics of hearing impairment. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:531–41. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins BE, Cramer CH, Silvius D, Zou D, Raymond RM, Orten DJ, Kimberling WJ, Smith RJ, Weil D, Petit C, Otto EA, Xu PX, Hildebrandt F. Transcription factor SIX5 is mutated in patients with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:800–4. doi: 10.1086/513322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N, Lee I, Marcotte EM, Hurles ME. Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar A, Orten DJ, Sorensen JL, Fischer SM, Cremers CW, Kimberling WJ, Smith RJ. SIX1 mutation screening in 247 branchio-oto-renal syndrome families: a recurrent missense mutation associated with BOR. Human mutation. 2008;29:565. doi: 10.1002/humu.20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug P, Moriniere V, Marlin S, Koubi V, Gabriel HD, Colin E, Bonneau D, Salomon R, Antignac C, Heidet L. Mutation screening of the EYA1, SIX1, and SIX5 genes in a large cohort of patients harboring branchio-oto-renal syndrome calls into question the pathogenic role of SIX5 mutations. Human mutation. 2011;32:183–90. doi: 10.1002/humu.21402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf K, Bollig F, Trowe MO, Besenbeck B, Ebert C, Kruspe D, Kispert A, Hanel F, Englert C. Sipl1 and Rbck1 are novel Eya1-binding proteins with a role in craniofacial development. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5764–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01645-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger S, Brand M. Fgf8 and Fgf3 are required for zebrafish ear placode induction, maintenance and inner ear patterning. Mechanisms of development. 2002;119:91–108. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Armstrong CM, Bertin N, Ge H, Milstein S, Boxem M, Vidalain PO, Han JD, Chesneau A, Hao T, Goldberg DS, Li N, Martinez M, Rual JF, Lamesch P, Xu L, Tewari M, Wong SL, Zhang LV, Berriz GF, Jacotot L, Vaglio P, Reboul J, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Li Q, Gabel HW, Elewa A, Baumgartner B, Rose DJ, Yu H, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Fraser A, Mango SE, Saxton WM, Strome S, Van Den Heuvel S, Piano F, Vandenhaute J, Sardet C, Gerstein M, Doucette-Stamm L, Gunsalus KC, Harper JW, Cusick ME, Roth FP, Hill DE, Vidal M. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science. 2004;303:540–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SL, Goddard JM, Capecchi MR. Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 have developmental defects in the tail and inner ear. Development. 1993;117:13–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T, Okada M, Usami S, Okuyama T. Phenotypic consequences in a Japanese family having branchio-oto-renal syndrome with a novel frameshift mutation in the gene EYA1. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:98–104. doi: 10.1080/00016480500527185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy A, Lord CJ, Savage K, Grigoriadis A, Smith DP, Weigelt B, Reis-Filho JS, Ashworth A. Conditional deletion of the Lkb1 gene in the mouse mammary gland induces tumour formation. The Journal of pathology. 2009;219:306–16. doi: 10.1002/path.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Gripp KW, Kirschner RE, Maisenbacher MK, Hustead V, Schauer GM, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Ciprero KL, Pasquariello P, Jr, LaRossa D, Bartlett SP, Whitaker LA, Zackai EH. Craniosynostosis: another feature of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;136A:358–62. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni L, Wagner MJ, Kimberling WJ, Pembrey ME, Grundfast KM, Kumar S, Daiger SP, Wells DE, Johnson K, Smith RJ. Refined localization of the branchiootorenal syndrome gene by linkage and haplotype analysis. American journal of medical genetics. 1994;51:176–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S, Strick R, Storer M, Huang N, Rad R, Willatt L, Fitzgerald T, Martin V, Sandford R, Carter NP, Janecke AR, Renner SP, Oppelt PG, Oppelt P, Schulze C, Brucker S, Hurles M, Beckmann MW, Strissel PL, Shaw-Smith C. High incidence of recurrent copy number variants in patients with isolated and syndromic Mullerian aplasia. J Med Genet. 2011;48:197–204. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.082412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gorman S. Second branchial arch lineages of the middle ear of wild-type and Hoxa2 mutant mice. Developmental Dynamics. 2005;234:124–131. doi: 10.1002/Dvdy.20402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orten DJ, Fischer SM, Sorensen JL, Radhakrishna U, Cremers CW, Marres HA, Van Camp G, Welch KO, Smith RJ, Kimberling WJ. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome (BOR): novel mutations in the EYA1 gene, and a review of the mutational genetics of BOR. Human mutation. 2008;29:537–44. doi: 10.1002/humu.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoi MF. Microduplication 22q11.2: a new chromosomal syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf RG, Berkman J, Wolf MT, Nurnberg P, Gattas M, Ruf EM, Hyland V, Kromberg J, Glass I, Macmillan J, Otto E, Nurnberg G, Lucke B, Hennies HC, Hildebrandt F. A gene locus for branchio-otic syndrome maps to chromosome 14q21.3-q24.3. Journal of medical genetics. 2003;40:515–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.7.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf RG, Xu PX, Silvius D, Otto EA, Beekmann F, Muerb UT, Kumar S, Neuhaus TJ, Kemper MJ, Raymond RM, Jr, Brophy PD, Berkman J, Gattas M, Hyland V, Ruf EM, Schwartz C, Chang EH, Smith RJ, Stratakis CA, Weil D, Petit C, Hildebrandt F. SIX1 mutations cause branchio-oto-renal syndrome by disruption of EYA1-SIX1-DNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308475101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson MG, Coughlin CR, 2nd, Kaplan P, Conlin LK, Meyers KE, Zackai EH, Spinner NB, Copelovitch L. Evidence for a recurrent microdeletion at chromosome 16p11.2 associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) and Hirschsprung disease. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2618–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Valle A, Wang X, Potocki L, Xia Z, Kang SH, Carlin ME, Michel D, Williams P, Cabrera-Meza G, Brundage EK, Eifert AL, Stankiewicz P, Cheung SW, Lalani SR. HERV-mediated genomic rearrangement of EYA1 in an individual with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2854–60. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanggaard KM, Rendtorff ND, Kjaer KW, Eiberg H, Johnsen T, Gimsing S, Dyrmose J, Nielsen KO, Lage K, Tranebjaerg L. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: detection of EYA1 and SIX1 mutations in five out of six Danish families by combining linkage, MLPA and sequencing analyses. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2007;15:1121–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannour-Louet M, Han S, Corbett ST, Louet JF, Yatsenko S, Meyers L, Shaw CA, Kang SH, Cheung SW, Lamb DJ. Identification of de novo copy number variants associated with human disorders of sexual development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischfield MA, Bosley TM, Salih MAM, Alorainy IA, Sener EC, Nester MJ, Oystreck DT, Chan WM, Andrews C, Erickson RP, Engle EC. Homozygous HOXA1 mutations disrupt human brainstem, inner ear, cardiovascular and cognitive development. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:1035–1037. doi: 10.1038/Ng1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VieilleGrosjean I, Hunt P, Gulisano M, Boncinelli E, Thorogood P. Branchial HOX gene expression and human craniofacial development. Developmental Biology. 1997;183:49–60. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent C, Kalatzis V, Abdelhak S, Chaib H, Compain S, Helias J, Vaneecloo FM, Petit C. BOR and BO syndromes are allelic defects of EYA1. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 1997;5:242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright TJ, Mansour SL. Fgf3 and Fgf10 are required for mouse otic placode induction. Development. 2003;130:3379–90. doi: 10.1242/dev.00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu PX, Adams J, Peters H, Brown MC, Heaney S, Maas R. Eya1-deficient mice lack ears and kidneys and show abnormal apoptosis of organ primordia. Nature genetics. 1999a;23:113–7. doi: 10.1038/12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu PX, Adams J, Peters H, Brown MC, Heaney S, Maas R. Eya1-deficient mice lack ears and kidneys and show abnormal apoptosis of organ primordia. Nat Genet. 1999b;23:113–7. doi: 10.1038/12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.