Abstract

Mounting pre-clinical evidence in rodents and non-human primates has demonstrated that prolonged exposure of developing animals to general anesthetics can induce widespread neuronal cell death followed by long-term memory and learning disabilities. In vitro experimental evidence from cultured neonatal animal neurons confirmed the in vivo findings. However, there is no direct clinical evidence of the detrimental effects of anesthetics in human fetuses, infants, or children. Development of an in vitro neurogenesis system using human stem cells has opened up avenues of research for advancing our understanding of human brain development and the issues relevant to anesthetic-induced developmental toxicity in human neuronal lineages. Recent studies from our group, as well as other groups, showed that isoflurane influences human neural stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis, while ketamine induces neuroapoptosis. Application of this high throughput in vitro stem cell neurogenesis approach is a major stride toward assuring the safety of anesthetic agents in young children. This in vitro human model allows us to (1) screen the toxic effects of various anesthetics under controlled conditions during intense neuronal growth, (2) find the trigger for the anesthetic-induced catastrophic chain of toxic events, and (3) develop prevention strategies to avoid this toxic effect. In this paper, we reviewed the current findings in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity studies, specifically focusing on the in vitro human stem cell model.

INTRODUCTION

A large body of experimental work has demonstrated that exposure of developing animals to most general anesthetics used clinically today, either volatile or intravenous, can induce widespread neuronal cell death followed by long-term memory and learning abnormalities.1–9 Anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity may depend on the following variables: (1) anesthetic dose, exposure duration, and number of exposures,10,11 (2) the receptor type being activated or inactivated,1,12 (3) single anesthetic or combination of different anesthetic agents,1 and (4) the stage of brain development.12–14 The window of the greatest vulnerability of the developing brain to anesthetics is restricted to the period of rapid synaptogenesis or the so-called brain growth spurt. This vulnerable period for anesthesia-induced neuroapoptosis appears to be very brief in animals occurring in rodents primarily during the first two weeks after birth. For rhesus monkeys this period ranges from approximately 115-day gestation up to postnatal day 60. In humans it starts from the third trimester of pregnancy and continues two to three years following birth.12,15–17 The underlying mechanisms of increased neurotoxicity following anesthetic exposure are not well understood. In addition, it is entirely unclear if anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment occurs in humans. Recent studies from our group and others showed that an in vitro human stem cell model can be used to study the effects of anesthetic agents on developing human neurons to determine whether or not anesthetic agents can induce toxicity in humans. In this paper, we reviewed the current findings obtained from intact animal and in vitro primary neuron culture models and the underlying mechanisms. We specially focused on the discussion of studies utilizing the human stem cell model.

IN VIVO ANIMAL MODEL

Anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity appears to only affect young animals. For example, isoflurane-induced neurodegeneration was only observed in young rats, but not in adult rats.13,14 Similar observations were also reported in mice and monkeys. Ketamine administered subcutaneously to 7-day-old mice for 5 h resulted in a significant increase in neuronal cell death.18 Intravenous administration of ketamine for 24 h caused an increase of cell death in the cortex of rhesus monkeys at 122 days of gestation and postnatal day 5.19 In a recent study, both fetal and neonatal monkeys were exposed to ketamine for 5 h. Ketamine caused a less widespread pattern and less dense concentration of neuroapoptosis in neonatal brains than in fetal brains.12 Additionally, sevoflurane anesthesia in pregnant mice (gestational day 14) also induced neurotoxicity in fetal and neonatal mice.4 Table 1 is a summary of some of the key animal studies to date examining anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.

Table 1.

Representative in vivo animal studies regarding the effect of general anesthetic-induced developmental neurotoxicity

| Anesthetics | Receptors | Dose | Duration | Animal model | Age | Apoptosis assay | Cognitive function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | GABAAR | 1 MAC | 4 hours | Rats | PD7 and PD 60 | FluoroJade Stain | Impaired spatial memory and hippocampal deficits | Stratmann et al. [14] |

|

| ||||||||

| Sevoflurane | GABAAR | 2.50% | 2 hours | 14 day gestation, pregnant mice | Fetal and P31 offspring | Caspase 3 | Impaired learning and memory | Zheng et al. [4] |

|

| ||||||||

| Ketamine | NMDAR | 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg/dose | Every 90 minutes for 6 hours | Rat | 7 days old | Caspase 3 | N/A | Soriano et al. [2] |

|

| ||||||||

| Ketamine | NMDAR | Neonates: 20–50 mg/kg/h Pregnant females: 10–85 mg/kg/h | 5 hours | Rhesus Macaques | PD 6 neonates and 120 day gestation fetuses | Caspase 3 | N/A | Brambrink et al. [12] |

|

| ||||||||

| Propofol | NMDAR and GABAAR | 50, 100 and 150 mg/kg | Every 90 minutes (4 times) | Mice | 5–7 days old | Caspase-3 | N/A | Cui et al. [11] |

|

| ||||||||

| Midazolam, nitrous oxide, and isoflurane | NMDAR and GABAAR | N2O: 50, 75, or 150 vol% Midazolam: 3, 6, or 9 mg/kg lso: 0.75, 1.0, or 1.5 vol% | 6 hours | Sprague Dawley Rats | 7 days old | Caspase-3 | Persistent memory and learning impairments | Jevtovic-Todorovic et al. [1] |

NMDAR: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor: GABAAR: gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor; MAC: minimum alveolar concentration; and PD: postnatal day.

IN VITRO PRIMARY NEURON CULTURE MODEL

In vitro experimental evidence from cultured neonatal animal neurons confirmed the in vivo findings.20–22 Vutskits et al. showed that 1 h exposure to ketamine at a concentration of 40 μM or greater induced toxicity in a primary culture of GABAergic neurons from postnatal day 0 rats.20 Treatment of neurons derived from fetal rats (gestational days 18–19) with 100 μM of ketamine for 48 h resulted in the loss of 45% of neurons by apoptosis.21 Similar toxic effects were also found in postnatal day 3 rhesus monkeys after 24 h of 10 μM ketamine exposure.22 The frontal cortex was the brain region that was found to be the most vulnerable to ketamine-induced neurotoxicity during development.36 The in vitro findings have been summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Representative in vitro studies regarding the effect of general anesthetic-induced developmental neurotoxicity

| Anesthetics | Dose | Duration | Cell sources | Apoptosis assay | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 MAC | 6 hours | Rat Hippocampal neurons | Caspase 3 | Zhao et al. [30] |

|

| |||||

| Isoflurane | 2% | 6 hours | H4 human neuroglioma cells and fetal mouse neurons | TUNEL | Zhang et al. [26] |

|

| |||||

| Ketamine | 100 μM | 24 hours | Human neurons derived from stem cells | TUNEL and Caspase 3 | Bai et al. [52] |

|

| |||||

| Ketamine | 0.01–40 μg/ml | 1–96 hours | PD 0 Sprague-Dawley rats-GABAergic interneurons | TUNEL | Vutskits et al. [20] |

|

| |||||

| Ketamine | 100 μM | 48 hours | Fetal Wistar rat cortical neurons | Caspase 3 | Takadera et al. [21] |

|

| |||||

| Ketamine | 1, 10 and 20 μM | 24 hours | PD3 rhesus monkey frontal cortical cultures | TUNEL | Wang et al. [22] |

| Propofol | 3 μM | 6 hours | Mouse cultured neurons | Caspase 3 | Pearn [39] |

MAC: minimum alveolar concentration; PD: postnatal day; and TUNEL: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling.

MECHANISMS OF ANESTHETIC-INDUCED NEUROTOXICITY

The underlying mechanisms of increased neurotoxicity following anesthetic exposure are complex and are not well understood. Although many different mechanisms and pathways have been implicated to play a role in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity, the mitochondria appear to play key roles in this process through their crucial involvement in cellular processes and apoptosis.23 However, many additional mechanisms have been proposed.

Trigger of Neurotoxicity

Apoptosis was shown to be involved in anesthetic-induced neuronal cell death.24–26 The mechanistic details by which anesthetics induce neurotoxicity have yet to be established. The vast majority of general anesthetics are N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonists and/or gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR) agonists. The NMDAR is involved in a variety of physiological processes, including memory, learning, and neuronal development. In the immature brain, GABA is the first neurotransmitter to become functional in developing networks and does not function as an inhibitory neurotransmitter as in the adult.27–29 GABAAR activation results in chloride efflux, depolarization of neurons, and induces a cytosolic calcium increase.30 Upregulation of NMDAR and/or overactivation of GABAAR may lead to excessive calcium entry, exceeding the buffering capacity of mitochondria. This can lead to a cascade of events including membrane potential depolarization, reactive oxygen species production, cytochrome c release into the cytosol, and caspase activation, ultimately resulting in neuroapoptosis.14,18,31,32 Ketamine is a non-competitive NMDAR antagonist. Withdrawal of ketamine induces compensatory upregulation of NMDAR expression followed by a toxic influx of calcium into neurons, leading to the elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and neuronal cell death. Administration of the antisense of NR1 can attenuate the ketamine-induced neuronal death.19,22,33–36 Isoflurane, a GABAAR agonist, was found to induce neurotoxicity in hippocampal neurons in culture via a GABAAR-mediated increase in intracellular calcium concentration.30,37 Some anesthetics might be less toxic, such as dexmedetomidine, because they do not affect the cellular receptors that are most commonly influenced by the majority of general anesthetics.38

Neuroinflammation

In addition to a direct influence on NMDAR and GABAAR, it was reported that anesthetic-induced neuroinflammation also plays an important role in the developing mouse brain and cognitive impairment. Anesthesia with 3% sevoflurane 2 h daily for 3 days induced cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation (e.g., increased interleukin-6 levels) in the developing mouse brain but not in adult mice. Anti-inflammatory treatment (ketorolac) attenuated the sevoflurane-induced cognitive impairment implicating neuroinflammation as a key mediator of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.11

Neurotrophins

Alterations in the levels of a variety of neurotrophins have been implicated to play a role in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity in the developing rodent brain. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is important to prosurvival signaling pathways. BDNF is stored as proneurotrophin (proBDNF) within synaptic vesicles and is proteolytically cleaved to mature BDNF (mBDNF) in the synaptic cleft by plasmin, a protease activated by tissue plasminogen activator. mBDNF triggers prosurvival signaling while proBDNF binds to the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) and activates RhoA that regulates actin cytoskeleton polymerization resulting in apoptosis. It has been shown that exposure of immature mouse neurons to propofol can induce neuroapoptosis through a proBDNF/p75NTR pathway. Knockout of p75NTR or administration of TAT-Pep5 (A specific p75NTR inhibitor) attenuated propofol-induced neuroapoptosis.39 Additionally, it was observed that exposure of rat pups to propofol induced a significant decrease in the thalamus in the level of nerve growth factor, a protein that is critical in the survival and growth of neurons. Propofol exposure was also shown to alter the expression levels of a variety of key neurotrophic factor receptors and downstream targets such as AKT and Erk.40 Taken together, these data suggest that altered neurotrophic factor expression following anesthetic exposure may also play a role in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.

Calcium Signaling

Intracellular calcium levels are tightly regulated under normal conditions due to key roles that calcium balance plays in various physiologic processes. Persistent increases in intracellular calcium, beyond normal levels, can induce apoptosis.41 It has recently been shown that intracellular calcium balance is disrupted in neurons following anesthetic exposure, implicating an important role for calcium disruption in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.32 Ketamine has been shown to suppress intracellular calcium oscillations and decrease the levels of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, a key protein in calcium regulation in a hippocampal cell culture model.42 It is well established that NMDA receptors play important roles in the regulation of intracellular calcium levels. Therefore, blockade of these receptors by anesthetics such as ketamine can lead to disrupted calcium levels indicating that calcium dysregulation may be a probable mechanism of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.

Mitochondrial Pathway

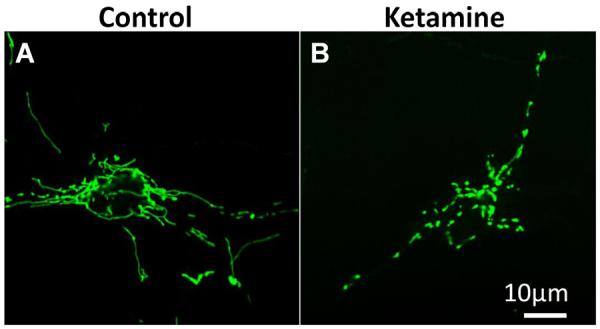

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that undergo continuous cycles of fusion and fission in order to maintain cellular homeostasis. Dynamics of mitochondrial fusion and fission result in the change of mitochondrial shape: either elongated, tubular, interconnected mitochondrial networks or fragmented and discontinuous mitochondria. Unbalanced fission-fusion can affect a variety of biological processes such as apoptosis and mitosis,43 leading to various pathological processes including neurodegenerative disease.44–47 Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) is a key regulator of mitochondrial fission. Drp1 is primarily distributed in the cytoplasm of a healthy cell, but shuttles between the cytoplasm and the mitochondrial surface. Phosphorylation of Drp1 at Serine 616 stimulates mitochondrial fission while phosphorylation at Serine 637 inhibits mitochondrial fission. Drp1 activates, translocates, and oligomerizes from the cytoplasm to the mitochondrial surface at fission sites to induce mitochondrial fission.48 Previous studies have shown that exposure of neonatal rat pups to general anesthetics induces significant increases in mitochondrial fission and leads to decreases in the level of Drp1 in the cytosol while increasing mitochondrial Drp1 levels.49 Inhibition of mitochondrial fission was shown to prevent mitochondrial cytochrome c release and apoptotic cell death.50 Loss of ΔΨm and release of cytochrome c from mitochondria are key events in initiating mitochondria-related apoptosis.51 Ketamine-induced apoptosis in stem cell-derived human neurons was accompanied by the significant decrease in ΔΨm and an increase in cytochrome c release from mitochondria into the cytosol. In addition, most control neurons showed elongated and inter-connected tubular mitochondria while much shorter and smaller mitochondria were prevalent in the ketamine-treated culture (Figures 1A and B),52 indicating the increased mitochondrial fission as possibly playing an important role in the toxic effects.

Fig 1. Ketamine increases mitochondrial fission.

Mitochondrial shape in the cells treated with or without 100 μM ketamine for 24 h. Differentiated neurons were labeled with CellLight™ mitochondria-GFP reagent and expressed GFP in the mitochondria. Mitochondria were elongated and interconnected in the control cells (A) while mitochondria were short and disconnected in the ketamine-treated culture (B).52

ROS Production

In response to ketamine, there was a significant increase in ROS production in the cytosol and superoxide generation within mitochondria in the ketamine-treated hESC-derived neurons, indicating a mitochondrial origin of ROS. Trolox, a ROS scavenger, prevented ketamine-induced ROS production and apoptosis in the differentiated human neurons.52 ROS are involved in the regulation of many physiological processes. However, overproduction of ROS under various cellular stresses can cause cell death. Mitochondria are a main source of ROS and the primary ROS is superoxide, which is converted to H2O2 either by spontaneous dismutation or by the enzyme superoxide dismutase. H2O2 can be further transformed to OH˙.53 In agreement with our data, several recent animal studies from other groups suggested that accumulation of ROS was associated with anesthetic-induced mitochondrial damage.26,31 Application of the antioxidant 7-nitroindazole (nitric oxide synthase inhibitor) provided protection against ketamine-induced neuronal cell death.54 These data suggest that the toxic effect can be prevented.

CONTROVERSY AS TO THE APPLICABILITY OF ANIMAL DATA TO CLINICAL ANESTHESIA PRACTICE

Although anesthesia neurotoxicity has been reported in several animal models,36,55–58 considerable controversy remains as to whether these findings are relevant to humans due to the following issues. First, the experimental conditions under which the data are collected from animals are different from those experienced by human neonates undergoing surgery and general anesthesia. It is clearly very hard to separate the effects of anesthetics alone from other quite relevant variables, including the impact of surgery and other factors related to acute/chronic diseases.5,59–61 Second, there may be interspecies differences in development and brain plasticity across mammalian species that allow humans to accommodate injury without clinically significant effects on neurodevelopment. For instance, the central components involved in apoptosis are a group of proteolytic enzymes called caspases which can be activated by various types of stimulation.62 There are species-specific (human vs. mouse) differences in the way caspases process their targets.63 Third, the neurodevelopmental impairments observed in animals, such as disruption of spontaneous behavior and poor performance in the Morris water maze, are of uncertain relevance to humans.13,58 Finally, experimental evidence provided thus far from in vitro cell culture and in vivo animal studies demonstrate that very high doses and prolonged exposure times are required to produce neurotoxic effects.22,30,35 A study from Wang's group demonstrated that six injections of 20 mg/kg ketamine produced the most severe neuronal damage in neocortical areas, especially in layers II and III of the frontal cortex. However, no significant effects were observed in the animals injected either one or three times with 20 mg/kg ketamine.22

LIMITATIONS OF CLINICAL EVIDENCE

It is well-documented that exposure to general anesthetics during very active brain growth and formation of synapses in animals results in considerable death of brain neurons and subsequent learning disabilities.1,64 So far, there is no direct clinical evidence showing any such effect in fetuses, infants, or children at any dose. If and how general anesthetics induce human neural cell toxicity is unknown. Similar studies in humans are not feasible. There are many obvious reason why studying the neurotoxic effects of various anesthetic agents in pediatric patients is not possible. It is impossible to thoroughly investigate the neurotoxic effects of anesthetics in fetuses, infants, and children. In addition, it is clearly very hard to separate the effects of anesthetics alone from other quite relevant variables including the impact of surgery and the factors associated with diseases.5 Moreover, it is not practical to either delay surgery in sick children or expose healthy children to anesthetic drugs in order to study these effects. It is also impossible to determine anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity using primary cultures of neonatal human neurons due to the limited access to human tissue.

Several epidemiological studies in humans have implicated that children exposed to anesthesia in early life have a higher incidence of learning disabilities later in life.59,60,65,66 These and subsequent studies evaluating multiple anesthetic exposures (e.g., three times) have shown detrimental effects on cognitive development in children (e.g., before age 4), and significant delays in measured intelligence, adaptive functioning, and academic performance.61,67–69 However, others found no significant differences. For instance, monozygotic twins discordant for having received anesthesia showed no significant difference in learning outcomes.70 There were no differences in educational outcomes at 15 to 16 years of age between 2,500 children with or without inguinal hernia repair.71 The discrepancy in the results of the epidemiological studies highlights the need for a better model by which to study this phenomenon. There is considerable ongoing effort to more fully understand the clinical significance anesthetic neurotoxicity. For instance, the US Food and Drug Administration and the International Anesthesia Research Society have formed a unique public-private partnership called SmartTots (smarttots.org) and several retrospective human studies are underway.

Each year, up to 2% of pregnant women in North America undergo anesthesia during their pregnancy for surgery unrelated to delivery of the fetus. In addition, millions of human fetuses, infants, and children are exposed to anesthetic drugs every year the United States and throughout the world. Thus, it is imperative to find a reliable mechanistic model to study whether or not clinically relevant doses of anesthetics induce developmental toxicity in human neurons. With the development of an in vitro neurogenesis system using human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and neural stem cells (NSCs), investigators can (1) study mechanisms of brain development, (2) screen the toxic effects of various anesthetics under controlled conditions (dose, number of exposures, or developmental stage) on human neuronal lineages such as NSCs and neurons, (3) dissect the underlying molecular mechanisms of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity, and (4) develop potential strategies for avoiding the toxic effect of anesthetics.

PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS

Pluripotent Capacity

hESCs are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of human blastocysts. These cells are able to replicate indefinitely in an undifferentiated state and differentiate into virtually every cell type found in the adult body.72 The differentiation ability of hESCs into committed stem cells or specific lineages is potentially valuable for: (1) tissue regeneration, (2) studying cellular and molecular events involved in early human development, (3) disease modeling, and (4) drug development and toxicity screening.33,73–76

iPSCs are reprogrammed from somatic cells such as skin fibroblasts and blood cells by transferring pluripotency factors (e.g., Oct-4, Klf4, Sox2, and cMyc). iPSCs are similar to hESCs in cell morphology, pluripotent marker expression (e.g., Oct-4 and SSEA4), proliferation, and differentiation potential. Despite the significant advances in hESC biology, issues such as ethical controversies and rejection with hESCs limit their utility. Development of iPSC technology provides an alternative pluripotent cell source. Specifically, iPSCs can be generated from any patient including those with heritable diseases and, therefore, carry the genotype of the patient they were derived from. Thus, development of iPSC technology offers the unique possibility of investigating the cellular consequences influenced by genetic vs. environmental factors in a human model and the underlying mechanisms. For instance, iPSCs obtained from patients with long QT syndrome recapitulate the long action potential phenotype features of inherited arrhythmias in the context of the patient's genetic background in cellular culture.77,78

Neuronal Lineage Differentiation

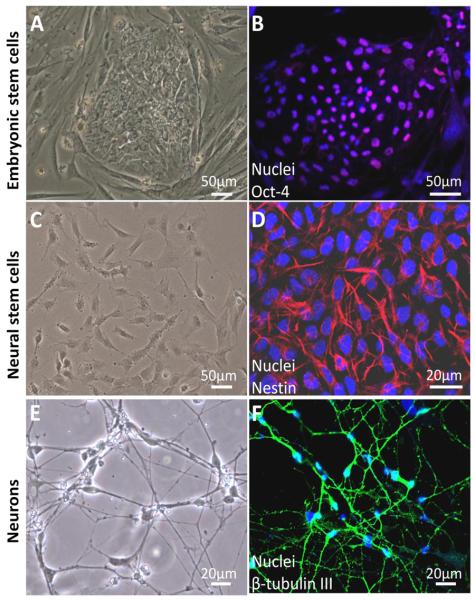

Both hESCs and iPSCs could differentiate into any type of human cells including NSCs by culturing them in chemically defined medium. During the differentiation process in our laboratory, hESCs were induced into NSCs and neurons following embryonic neuronal developmental principles.52,79,80 hESCs, NSCs, and neurons were characterized by cell morphology and cell-specific marker expression as follows. hESCs were grown as uniform flat colonies on mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells (Figure 2A). hESCs expressed pluripotent stem cell markers Oct-4 (Figure 2B) and SSEA-4. NSCs showed triangle-like morphology (Figure 2C) and expressed the NSC marker nestin (Figure 2D). They had strong proliferation potential and were passaged every 5–6 days.52 In addition, they were able to differentiate into neuronal lineages: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. NSCs can also be directly isolated from fetal or adult nervous tissue.81

Fig 2. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into neural stem cells (NSCs) and neurons.

hESCs grew as uniform flat colonies on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (A). hESCs expressed pluripotent stem cell markers Oct-4 (b, pink). Blue are cell nuclei (B). NSCs grew as a monolayer in the dish coated with Matrigel (C). NSCs were positive for the NSC-specific marker, nestin (g, red) (D). Two weeks after culturing NSCs in neuronal differentiation medium, cells demonstrated neuron-like morphology with small round cell bodies and extending long projections (E). Differentiated cells were positive for the neuron-specific marker, β-tubulin III (b, green) (F).52

Neuronal differentiation was observed by morphological assessment in the culture after six days of culturing the NSCs in neuronal differentiation medium. Differentiated neurons exhibited round cell shape with small projections. Cell projections extended and the extensive neuron networks were further formed in the culture over time (Figure 2E). Two-week-old neurons expressed neuron-specific markers β-tubulin III (Figure 2F) and microtubule-associated protein 2. In addition, these differentiated neurons expressed the synaptic marker synapsin-1 which is exclusively localized in the regions occupied by synaptic vesicles. They also expressed postsynaptic protein Homer 1, a family of postsynaptic scaffolding proteins.52,82,83 In addition, differentiated neurons exhibited functional synapse.84 The differentiation efficiency of NSCs into neurons was over 90%.52 Recapitulation of neurogenesis from hESCs in vitro provide a valuable and promising tool for the investigation of varying drug-induced developmental neurotoxicity which is difficult to study in human patients.

ADVANTAGES OF IN VITRO STEM CELL NEUROGENESIS MODEL

The greatest vulnerability of the developing brain to anesthetics occurs at the time of the brain growth spurt period. Many developmental events, including proliferation, migration, differentiation, formation of axons and dendrites, and synaptogenesis occur within this period. Thus, neuronal cell death may not be the only consequence of general anesthetics. Anesthetics may perturb neural development by influencing NSC proliferation, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neuronal survival.85,86 Thus, our in vitro human stem cell model is promising for high throughput examination of anesthetic-induced developmental neurotoxicity.

There are five main advantages of this experimental model in addressing the critical issues relevant to the anesthetic neurotoxicity: (1) providing unlimited human NSCs and neurons for neurotoxicity study, (2) screening the neurotoxic effect of various anesthetics under controlled conditions (e.g., dose, duration and frequency of drug exposure), (3) allowing the dissection of the toxic effects of varying anesthetics on various stages of neuronal cell development, the individual neurodevelopment process, and the underlying molecular mechanisms, (4) investigating the potential preventive strategies to avoid this toxic effect, and (5) eliminating the need for a large number of animals. This approach was recently also used to examine the effects of alcohol on human NSCs, showing a dramatic phenotype of proliferation in response to ethanol.87

CURRENT FINDINGS FROM STEM CELL NEUROGENESIS MODEL

Using this in vitro human stem cell neurogenesis approach we have examined for the first time the effect of anesthetics on hESC-derived NSCs and neurons.52,79 We used the intravenous anesthetic agent ketamine which is widely used in pediatric anesthesia to provide sedation/analgesia to children during surgery or imaging. Ketamine and isoflurane are two of the most widely studied anesthetics for addressing neurotoxicity issues in rodent and primate models and cell culture model.5–9,18–22,88 Using this in vitro stem cell neurogenesis model our and other's most recent studies showed that these two drugs could influence neuronal developmental progress including NSC proliferation, neurogenesis, and neuronal viability as detailed below.52,89

Neural Stem Cell Proliferation

In our study, NSCs were treated with 100 μM ketamine for 6 h. Ki67 immunofluorescence staining and bromodeoxyurindine (BrdU) assay were performed for evaluation of cell proliferation. Ki67 is a nuclear, non-histone protein and is preferentially expressed during late G1, S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle; while resting, non-cycling cells (G0 phase) lack Ki67 expression. There were more Ki67-positive cells in the 6 h ketamine-treated culture compared with the control group. BrdU is a thymidine analog and can be incorporated into newly synthesized DNA strands of actively proliferating cells. The extent of BrdU incorporation allows for the assessment of cell proliferation rate. Consistent with the Ki67 staining, ketamine significantly increased BrdU incorporation after 6 h of exposure.52 The ketamine-induced increase in NSC proliferation was also observed in rats.90 However a recent in vitro study showed that ketamine decreased rat cortical NSC proliferation.91 The observed differences in the ketamine on NSC proliferation may be due to the use of different models. A recent study also found the enhanced proliferation in human neural progenitor cell line, ReNcell CX (immortalized by retroviral transduction with the c-myc oncogene).89 These cells were derived from the cortical region of human fetal brain. Increased proliferation of these neural progenitor cells were shown at a low concentration (0.6%) of isoflurane while no effect was seen using a clinically relevant concentration (1.2%). Decreased proliferation was observed at a high concentration of isoflurane (2.4%).89 Abnormal proliferation of NSCs could influence neurodevelopment. Ethanol, an NMDA antagonist, has long been recognized to be neurotoxic to the developing brain. Exposure to ethanol during brain development might promote neurodevelopmental defects.92,93 In one recent study, Nash et al. used the similar in vitro hESC-based neurogenesis system to study ethanol-induced early developmental toxicity.87 They found that ethanol induced a complex mix of phenotypic changes, including an inappropriate increase in stem cell proliferation and loss of trophic astrocytes. Thus, ketamine-induced alterations in NSC proliferation might also contribute to abnormal brain development.

Neurogenesis

Shorter exposure (1 h) to a high dose of isoflurane (2.4%) had no effect on the differentiation of neural progenitor cell line (ReNcell CX) into neurons and astrocytes.89 However, prolonged exposure (24 h) to the same concentration of isoflurane significantly suppressed neuronal differentiation and promoted glial differentiaiton. This toxic effect may be attributed to differential regulation of calcium release through activation of endoplasmic reticulum localized inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and/or ryanodine receptors. Pretreatment of ReNcell cultures with inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate or ryanodine receptor antagonists (xestospongin C and dantrolene, respectively) mostly prevented isoflurane-mediated effects on the neuronal differentiation.89

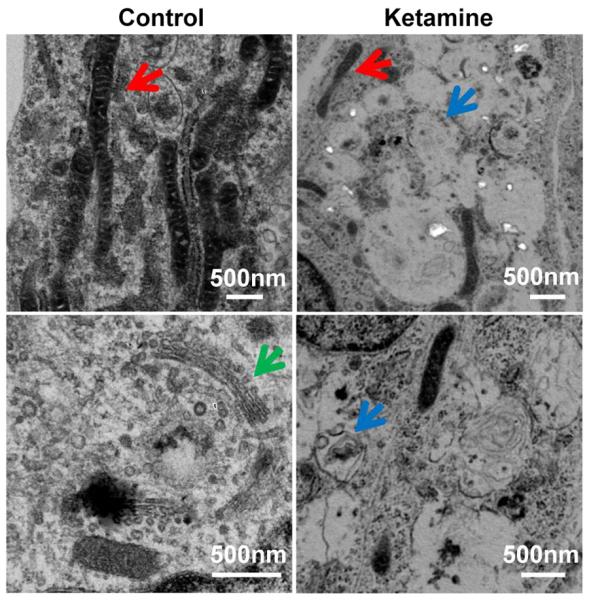

Ultrastructure in Neurons

Our electron microscopic images demonstrate the toxic effects on the cellular ultrastructure in ketamine-treated human neurons derived from hESCs. The neurons without ketamine treatment had very elongated mitochondria, while the ketamine-treated neurons displayed fragmented mitochondria. In addition, in the 24 h of 100 μM ketamine-treated culture, large oval-shaped autophagosomes having some membrane-like material within them were found in almost every cell occupying the majority of the cytosol volume. Another observation was the disappearance of Golgi structures in the ketamine-treated neurons (Figure 3).52

Fig 3. Ketamine causes abnormal cellular changes in ultrastructure.

Representative electron microscope images of differentiated neurons treated with the indicated concentrations of ketamine for 24 h. Ketamine-treated neurons showed clear signs of the toxicity on the cellular ultrastructure. Abnormal ultrastructure of neurons included mitochondrial fragmentation and many autophagosomes with or without being packed with dense amorphous material. In addition, Golgi structures in the 100 μM ketamine-treated cells were not observed. Red, blue, and green arrows indicate mitochondria, autophagosome, and Golgi, respectively.52

Neuroapoptosis

Neuronal apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is commonly recognized as one of the detrimental effects of anesthetics.2,21,94 However, how anesthetics induce neuronal apoptosis is not well understood. The central components of the programmed cell death are a group of proteolytic enzymes called caspases which can be activated by various types of stimulation. The released cytochrome c activates caspase 9, which consequently induces caspase 3 activation, resulting in the cleavage of several cellular proteins, and finally, leading to the typical alterations related to cell apoptosis such as DNA fragmentation in cell nuclei.26,94 DNA fragmentation can be used to detect apoptotic cells by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. When compared with no-treatment, prolonged exposure (24 h) of 100 μM ketamine significantly increased caspase 3 activity. Consistent with caspase 3 activation, more TUNEL-positive cells with condensed and fragmented nuclei were observed in ketamine-treated cultures.52

These findings from human stem cell-derived neurons were largely in line with several previous studies showing that only prolonged exposure and/or high doses of anesthetics could induce neuronal death.57 For instance, 24 h of 10 μM ketamine exposure induced a significant loss of postnatal day 3 monkey frontal cortical neurons in culture.22 In another study, treatment with 100 μM of ketamine for 48 h resulted in the loss of 45% of neurons from fetal rats at 18–19 days gestation.21 Several recent reports showed that only superclinical concentration of anesthetics could induce neurotoxicity. Mak et al demonstrated that administration of 4000 μM ketamine for 48 h caused significant death of both primary human neurons and differentiated neurons from human neuroblastoma SH-SYY5 cell line.95 This finding was supported by Braun et al. who showed the significant increase in the number of apoptotic neurons differentiated from human neuroblastoma SHEP cell line after 24 h of 2000 μM ketamine treatment.94 The similar finding was also reported in primary cortical neurons from postnatal day 2–8 in mice.96

The observed toxic threshold of ketamine varies in different studies because: (1) the vulnerability of neurons from different species to ketamine may differ, and/or (2) the neurons used in different studies might be at different developmental stages or contain different percentages of neurons, influencing the vulnerability to ketamine. It is commonly considered that developing mammals are at greatest apoptotic risk during the most rapid period of growth of their central nervous system. Many developmental events, including neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neuron structure remodeling, occur within this period. Thus, neurons at different stages of brain growth burst might also exhibit different sensitivity to ketamine. It is also possible for ketamine at low concentrations to be able to alter other cell physiological activities, including neuronal receptor expression, the structure and branching of neurons' dendrites, and synaptogenesis, eventually resulting in impaired neuronal function. Additionally, in vitro neuron culture system excludes the influence of other environmental factors (such as astrocytes and growth factors) in vivo that may increase toxic threshold of ketamine. Short term and low-dose anesthetics might be a safer strategy for a brief procedure or other sedation in children.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVE

A large body of recent work suggests that neuroapoptosis is a major mechanism responsible for the progression of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity. However, as we showed earlier, developing mammals are at greatest apoptotic risk during the most rapid period of brain growth. Many developmental events (e.g., neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neuron structure remodeling) occur within this period. Thus, we have considered that neuronal cell death may not be the only consequence caused by general anesthetics. The in vitro hESC-related neurogenesis model can mimic the in vivo neuronal development process, providing a simple and promising in vitro human model and unlimited cell source for addressing such important anesthesia-related issues. Importantly, this approach has a potential translational application because identification of the cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways that underlie anesthesia neurotoxicity will allow targeting of the molecules that can prevent this toxic effect. In addition, this established in vitro experimental model will provide numerous possibilities for future studies as one could use this high throughput approach to test the effects of various conditions and anesthetics (e.g., isoflurane and midazolam) on developing human neurons, which will lead to major advances toward assuring the safety of anesthesia for fetuses and infants.

As to the clinical practice, clearly more evidence is needed to guide clinical decision-making on the safety of anesthesia during pregnancy as well as pediatric anesthesia. The National Center for Toxicological Research, an internationally recognized research center at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and several universities are conducting research regarding the effects of anesthetics on the nervous systems of animals during developmental periods of rapid brain growth (smarttots.org). Currently, there is not sufficient evidence to determine whether these findings are translatable to the millions of young children who receive anesthesia each year. Despite the unequivocal neurotoxic effect of anesthetics in animal models, there is no direct clinical evidence showing any such effect in fetuses, infants, or children at any dose. The development of the research in the area of stem cell biology and neuroscience will advance our understanding of anesthetic neurotoxicity. The ultimate goal would be not only to find the trigger for this catastrophic chain of events, but also to prevent neuronal cell death itself.

One of the major caveats with this in vitro stem cell study lies in the relevance of the in vitro model to a true in vivo system. Specifically, there are many cell types present in the human brain including neurons and glial cells, all of which interact extensively. Utilizing cultures of pure neurons may not allow for the accurate assessment of the effects of anesthetics on intact brains. Thus, it will be necessary to confirm the in vitro findings in animal models including non-human primates. A second limitation of this model is the use of neurons derived from human stem cells. The ideal model for these types of studies would be neurons that have been harvested from a developing human brain. However, such a model is currently not feasible and would likely not yield enough cells for the studies. While neurons derived from stem cells may not exactly mimic human brain environment, they express several important neuronal markers and functional synapse, representing an acceptable and promising model.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by P01GM066730, R01HL034708 from the NIH, Bethesda, MD, and by FP00003109 from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Research and Education Initiative Fund (to Dr. Bosnjak).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soriano SG, Liu Q, Li J, et al. Ketamine activates cell cycle signaling and apoptosis in the neonatal rat brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1155–1163. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d3e0c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma D, Williamson P, Januszewski A, et al. Xenon mitigates isoflurane-induced neuronal apoptosis in the developing rodent brain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:746–753. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264762.48920.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng H, Dong Y, Xu Z, et al. Sevoflurane Anesthesia in Pregnant Mice Induces Neurotoxicity in Fetal and Offspring Mice. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:516–526. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182834d5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loepke AW, Soriano SG. An assessment of the effects of general anesthetics on developing brain structure and neurocognitive function. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1681–1707. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318167ad77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Pediatric anesthesia neurotoxicity: an overview of the 2011 SmartTots panel. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:965–968. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182326622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boscolo A, Starr JA, Sanchez V, et al. The abolishment of anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment by timely protection of mitochondria in the developing rat brain: the importance of free oxygen radicals and mitochondrial integrity. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu F, Paule MG, Ali S, Wang C. Ketamine-induced neurotoxicity and changes in gene expression in the developing rat brain. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:256–261. doi: 10.2174/157015911795017155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mellon RD, Simone AF, Rappaport BA. Use of anesthetic agents in neonates and young children. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:509–520. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255729.96438.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scallet AC, Schmued LC, Slikker W, Jr., et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of ketamine: morphometric confirmation, exposure parameters, and multiple fluorescent labeling of apoptotic neurons. Toxicol Sci. 2004;81:364–370. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui Y, Ling-Shan G, Yi L, et al. Repeated administration of propofol upregulated the expression of c-Fos and cleaved-caspase-3 proteins in the developing mouse brain. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:648–651. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.89819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Ketamine-induced neuroapoptosis in the fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:372–384. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242b2cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredriksson A, Ponten E, Gordh T, Eriksson P. Neonatal exposure to a combination of N-methyl-D-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor anesthetic agents potentiates apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent behavioral deficits. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:427–436. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278892.62305.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratmann G, Sall JW, May LD, et al. Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:834–848. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrow BA, Roth RH, Redmond DE, Jr., Sladek JR, Jr., Elsworth JD. Apoptotic natural cell death in developing primate dopamine midbrain neurons occurs during a restricted period in the second trimester of gestation. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dekaban AS. Changes in brain weights during the span of human life: relation of brain weights to body heights and body weights. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:345–356. doi: 10.1002/ana.410040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young C, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Qin YQ, et al. Potential of ketamine and midazolam, individually or in combination, to induce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the infant mouse brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:189–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slikker W, Jr., Zou X, Hotchkiss CE, et al. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:145–158. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vutskits L, Gascon E, Tassonyi E, Kiss JZ. Effect of ketamine on dendritic arbor development and survival of immature GABAergic neurons in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:540–549. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takadera T, Ishida A, Ohyashiki T. Ketamine-induced apoptosis in cultured rat cortical neurons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;210:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Sadovova N, Hotchkiss C, et al. Blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by ketamine produces loss of postnatal day 3 monkey frontal cortical neurons in culture. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:192–201. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei X, Guo Q, Zhang J. Mechanistic insights into neurotoxicity induced by anesthetics in the developing brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:6772–6799. doi: 10.3390/ijms13066772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Sadovova N, Fu X, et al. The role of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in ketamine-induced apoptosis in rat forebrain culture. Neuroscience. 2005;132:967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Istaphanous GK, Howard J, Nan X, et al. Comparison of the neuroapoptotic properties of equipotent anesthetic concentrations of desflurane, isoflurane, or sevoflurane in neonatal mice. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:578–587. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182084a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Dong Y, Wu X, et al. The mitochondrial pathway of anesthetic isoflurane-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4025–4037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:728–739. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:703–708. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c42a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei H, Xie Z. Anesthesia, calcium homeostasis and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:30–35. doi: 10.2174/156720509787313934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao YL, Xiang Q, Shi QY, et al. GABAergic excitotoxicity injury of the immature hippocampal pyramidal neurons' exposure to isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1152–1160. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318230b3fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C, Zhang X, Liu F, Paule MG, Slikker W., Jr. Anesthetic-induced oxidative stress and potential protection. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1473–1482. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei H. The role of calcium dysregulation in anesthetic-mediated neurotoxicity. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:972–974. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182323261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredriksson A, Archer T, Alm H, Gordh T, Eriksson P. Neurofunctional deficits and potentiated apoptosis by neonatal NMDA antagonist administration. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F, Patterson TA, Sadovova N, et al. Ketamine-induced neuronal damage and altered N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor function in rat primary forebrain culture. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:548–557. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Q, Guo L, Patterson TA, et al. Gene expression profiling in the developing rat brain exposed to ketamine. Neuroscience. 2010;166:852–863. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou X, Patterson TA, Sadovova N, et al. Potential neurotoxicity of ketamine in the developing rat brain. Toxicol Sci. 2009;108:149–158. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei H, Kang B, Wei W, et al. Isoflurane and sevoflurane affect cell survival and BCL-2/BAX ratio differently. Brain Res. 2005;1037:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, et al. Dexmedetomidine attenuates isoflurane-induced neurocognitive impairment in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1077–1085. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819daedd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearn ML, Hu Y, Niesman IR, et al. Propofol neurotoxicity is mediated by p75 neurotrophin receptor activation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:352–361. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242a48c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popic J, Pesic V, Milanovic D, et al. Propofol-induced changes in neurotrophic signaling in the developing nervous system in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: The calcium-apoptosis link. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinner B, Friedrich O, Zink W, Zausig Y, Graf BM. The toxic effects of s(+)-ketamine on differentiating neurons in vitro as a consequence of suppressed neuronal Ca2+ oscillations. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1161–1169. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31822747df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, et al. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2010;121:2012–2022. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in the control of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Youle RJ, Karbowski M. Mitochondrial fission in apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:657–663. doi: 10.1038/nrm1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batlevi Y, La Spada AR. Mitochondrial autophagy in neural function, neurodegenerative disease, neuron cell death, and aging. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rambold AS, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Mechanisms of mitochondria and autophagy crosstalk. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4032–4038. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao J, Liu T, Jin S, et al. Human MIEF1 recruits Drp1 to mitochondrial outer membranes and promotes mitochondrial fusion rather than fission. EMBO J. 2011;30:2762–2778. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boscolo A, Milanovic D, Starr JA, et al. Early Exposure to General Anesthesia Disturbs Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion in the Developing Rat Brain. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1086–1097. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318289bc9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, et al. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:515–525. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budd SL, Tenneti L, Lishnak T, Lipton SA. Mitochondrial and extramitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathways in cerebrocortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6161–6166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100121097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai X, Yan Y, Canfield S, et al. Ketamine enhances human neural stem cell proliferation and induces neuronal apoptosis via reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2013;116:869–880. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182860fc9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang C, Sadovova N, Patterson TA, et al. Protective effects of 7-nitroindazole on ketamine-induced neurotoxicity in rat forebrain culture. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGowan FX, Jr., Davis PJ. Anesthetic-related neurotoxicity in the developing infant: of mice, rats, monkeys and, possibly, humans. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1599–1602. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817330cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rizzi S, Carter LB, Ori C, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Clinical anesthesia causes permanent damage to the fetal guinea pig brain. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zou X, Patterson TA, Divine RL, et al. Prolonged exposure to ketamine increases neurodegeneration in the developing monkey brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2009;27:727–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCann ME, Bellinger DC, Davidson AJ, Soriano SG. Clinical research approaches to studying pediatric anesthetic neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:766–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davidson AJ, McCann ME, Morton NS, Myles PS. Anesthesia and outcome after neonatal surgery: the role for randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:941–944. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818e3f79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hansen TG, Flick R. Anesthetic effects on the developing brain: insights from epidemiology. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1–3. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181915926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Kakavouli A, Byrne MW, Li G. A retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young children. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;21:286–291. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a71f11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ussat S, Werner U, Adam-Klages S. Species-specific differences in the usage of several caspase substrates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1186–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chalon J, Tang CK, Ramanathan S, et al. Exposure to halothane and enflurane affects learning function of murine progeny. Anesth Analg. 1981;60:794–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun LS, Li G, Dimaggio C, et al. Anesthesia and neurodevelopment in children: time for an answer? Anesthesiology. 2008;109:757–761. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818a37fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sprung J, Flick RP, Katusic SK, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder after early exposure to procedures requiring general anesthesia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1053–1061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalkman CJ, Peelen L, Moons KG, et al. Behavior and development in children and age at the time of first anesthetic exposure. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:805–812. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, et al. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartels M, Althoff RR, Boomsma DI. Anesthesia and cognitive performance in children: no evidence for a causal relationship. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:246–253. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hansen TG, Pedersen JK, Henneberg SW, et al. Academic Performance in Adolescence after Inguinal Hernia Repair in Infancy: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Anesthesiology. 2011 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820e77a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shin S, Dalton S, Stice SL. Human motor neuron differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:266–269. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vidarsson H, Hyllner J, Sartipy P. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes for in vitro and in vivo applications. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;6:108–120. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bissonnette CJ, Lyass L, Bhattacharyya BJ, et al. The controlled generation of functional Basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:802–811. doi: 10.1002/stem.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mandenius CF, Andersson TB, Alves PM, et al. Toward preclinical predictive drug testing for metabolism and hepatotoxicity by using in vitro models derived from human embryonic stem cells and human cell lines - a report on the Vitrocellomics EU-project. Altern Lab Anim. 2011;39:147–171. doi: 10.1177/026119291103900210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Di Pasquale E, Condorelli G. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in studies of inherited arrhythmias. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:84–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI62838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bosnjak ZJ, Yan Y, Canfield S, et al. Ketamine induces toxicity in human neurons differentiated from embryonic stem cells via mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Curr Drug Saf. 2012;7:106–119. doi: 10.2174/157488612802715663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu BY, Weick JP, Yu J, et al. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cattano D, Young C, Straiko MM, Olney JW. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1712–1714. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172ba0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirokawa N, Sobue K, Kanda K, Harada A, Yorifuji H. The cytoskeletal architecture of the presynaptic terminal and molecular structure of synapsin 1. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:111–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kammermeier PJ. Endogenous homer proteins regulate metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling in neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8560–8567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1830-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson MA, Weick JP, Pearce RA, Zhang SC. Functional neural development from human embryonic stem cells: accelerated synaptic activity via astrocyte coculture. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3069–3077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4562-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De Roo M, Klauser P, Briner A, et al. Anesthetics rapidly promote synaptogenesis during a critical period of brain development. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Culley DJ, Boyd JD, Palanisamy A, et al. Isoflurane decreases self-renewal capacity of rat cultured neural stem cells. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:754–763. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318223b78b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nash R, Krishnamoorthy M, Jenkins A, Csete M. Human embryonic stem cell model of ethanol-mediated early developmental toxicity. Exp Neurol. 2011;234:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haley-Andrews S. Ketamine: the sedative of choice in a busy pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:186–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao X, Yang Z, Liang G, et al. Dual Effects of Isoflurane on Proliferation, Differentiation, and Survival in Human Neuroprogenitor Cells. Anesthesiology. 2013 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182833fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keilhoff G, Bernstein HG, Becker A, Grecksch G, Wolf G. Increased neurogenesis in a rat ketamine model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dong C, Rovnaghi CR, Anand KJ. Ketamine alters the neurogenesis of rat cortical neural stem progenitor cells. Crit Care Med. 2012 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318253563c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miller MW. Effects of alcohol on the generation and migration of cerebral cortical neurons. Science. 1986;233:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.3749878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller MW. Mechanisms of ethanol induced neuronal death during development: from the molecule to behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:128A–132A. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Braun S, Gaza N, Werdehausen R, et al. Ketamine induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway in human lymphocytes and neuronal cells. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:347–354. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mak YT, Lam WP, Lu L, Wong YW, Yew DT. The toxic effect of ketamine on SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line and human neuron. Microsc Res Tech. 2010;73:195–201. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Campbell LL, Tyson JA, Stackpole EE, et al. Assessment of general anaesthetic cytotoxicity in murine cortical neurones in dissociated culture. Toxicology. 2011;283:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]