Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder prevalence in primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric complaints has been measured in several studies but has not been systematically reviewed.

Objective

To systematically review studies measuring bipolar disorder prevalence in primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric complaints.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using the PRISMA method in January 2013. We searched seven databases using a comprehensive list of search terms. Included articles had a sample size of 200 patients or more and assessed bipolar disorder using a structured clinical interview or bipolar screening questionnaire in adult primary care patients with a prior diagnosis of depression or had an alternate psychiatric complaint.

Results

Our search yielded 5595 unique records. Seven cross-sectional studies met our inclusion criteria. The percentage of primary care patients with bipolar disorder was measured in four studies of patients with depression, one study of patients with trauma exposure, one study of patients with any psychiatric complaint and one study of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. The percentage of patients with bipolar disorder ranged from 3.4% to 9% in studies using structured clinical interviews and from 20.9% to 30.8% in studies using screening measures.

Conclusions

Bipolar disorder likely occurs in 3 – 9% of primary care patients with depression, trauma exposure, medically unexplained symptoms or a psychiatric complaint. Screening measures used for bipolar disorder detection overestimate the occurrence of bipolar disorder in primary care due to false positives.

Background

Depressive and anxiety disorders commonly occur in primary care patients1. Major depression occurs in approximately 5-10% of the general primary care population2, up to 20% of primary care patients with coronary heart disease or diabetes3, and 20% of primary care patients from lower socioeconomic stratas4. One or more anxiety disorders were found in almost 20% of primary care patients in one study5. Because these disorders commonly occur in primary care, and are associated with significant functional impairment6, screening measures have been developed to identify patients likely to have a depressive or anxiety disorder.

The Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9)7 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)5 have been widely used in primary care to improve the recognition and treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. However not everyone who screens positive on a screening measure has depression or anxiety8. Some patients with false positive screens may have bipolar disorder, a mood disorder characterized by recurrent depressive episodes and at least one manic episode (for bipolar I disorder) or hypomanic episode (for bipolar II disorder)9.

Patients with bipolar disorder experience major depression or depressive symptoms more often than manic symptoms10,11. Additionally, anxiety disorders co-occur in almost three-quarters of patients with bipolar disorder12. Therefore, many patients with bipolar disorder will initially present to primary care with depressive or anxiety symptoms.

Previous investigators have sought to determine the prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression. In an early small study, Manning, et al.13 conducted structured clinical interviews in 108 consecutive primary care patients with depression or anxiety. Approximately one quarter of the patients were found to have a history consistent with bipolar disorder, with bipolar II disorder occurring in 20 patients and bipolar I disorder occurring in 3 patients. Subsequent studies have sought to measure the prevalence of bipolar disorder in larger samples of primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric disorders using various methods to diagnose bipolar disorder.

To our knowledge no systematic review has synthesized the results from these studies. We sought to systematically review the literature on the prevalence of bipolar disorder among primary care patients already diagnosed with depression or presenting to primary care with other psychiatric complaints. Understanding the prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric complaints could lead to improved recognition and treatment of bipolar disorder in primary care. Lack of recognition of bipolar disorder in a patient presenting with depression could result in treatment of bipolar depression with an antidepressant medication. Although some evidence suggests that antidepressant monotherapy may be beneficial in the maintenance treatment of bipolar II disorder14, a meta-analysis has shown that antidepressant monotherapy lacks efficacy in the acute treatment of bipolar depression15 and could worsen the clinical course of acute bipolar depression16. Understanding the previous studies’ methodologic strengths and limitations could inform the design of a study to accurately measure the prevalence of bipolar disorder among primary care patients with depression.

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method to conduct and report this review17. The PRISMA method suggests measuring the risk of bias of individual intervention studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool18. Our objective was to review only cross-sectional studies, not intervention studies, so risk of bias was not measured. This review was not registered in a systematic review registry.

Search technique

We searched PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsychInfo and 3 sections of the Cochrane Library, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. All databases were searched from their inception to January 15, 2013 and the total number of citations retrieved was 6,149. Endnote software was employed to remove 555 duplicate citations and the final number of citations screened was 5,594 with one additional citation identified after the search was completed.

The PubMed database was searched with a combination of MeSH headings and words occurring in the title or abstracts of PubMed records. Editorials, letters and comments were excluded and citations were limited to English language. To capture the citations relating to primary care these terms were combined with an “OR.” (“Primary Health Care”[Mesh] OR “Physicians, Primary Care”[Mesh] OR “Primary Care Nursing”[Mesh] OR “Nurse Practitioners”[Mesh] OR “Internal Medicine”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Adolescent Medicine”[Mesh] OR “General Practice”[Mesh] OR “Military Medicine”[Mesh] OR “Community Medicine”[Mesh] OR “Family Physicians”[Mesh] OR “primary care[tiab] OR “general practice”[tiab] OR “general practitioner”[tiab] OR “general practitioners”[tiab] OR “nurse practitioner”[tiab] OR “nurse practitioners”[tiab] or “family medicine”[tiab] OR “family practice”[tiab] OR “family physician”[tiab] OR “family physicians”[tiab]). These primary care concepts were then combined with the following terms: (“Affective Disorders, Psychotic”[Mesh] OR “Mental Disorders”[Mesh:noexp] OR bipolar[tiab] OR mania[tiab] OR manic[tiab] OR “manic depression”[tiab] OR “manic depressive”[tiab]). The PubMed strategy was then reproduced in each of the other databases.

Eligibility

Article titles and selected abstracts returned from the search were screened for topic relevance. Selected full text articles were assessed for eligibility. Eligible articles included studies in English that evaluated the presence of bipolar disorder using either a structured interview, clinical examination, or screening measure in samples of 200 or more primary care patients 18 years and older with depression or a psychiatric complaint. Reference lists of the selected studies were also scanned to identify additional articles.

Exclusion

Studies were excluded if they focused on populations outside of primary care, or did not evaluate patients for the presence of bipolar disorder. Studies examining bipolar disorder prevalence in a sample of random primary care patients, in samples with fewer than 200 patients, or in children or adolescents were also excluded.

Data abstraction

One author (J.M.C) abstracted information about each included study onto a data collection tool. Abstracted information included the details of population studied (e.g. random or convenience sample), sample size, method of diagnosing bipolar disorder, prevalence measurement, standard comparison and associated operating characteristics (if included).

Results

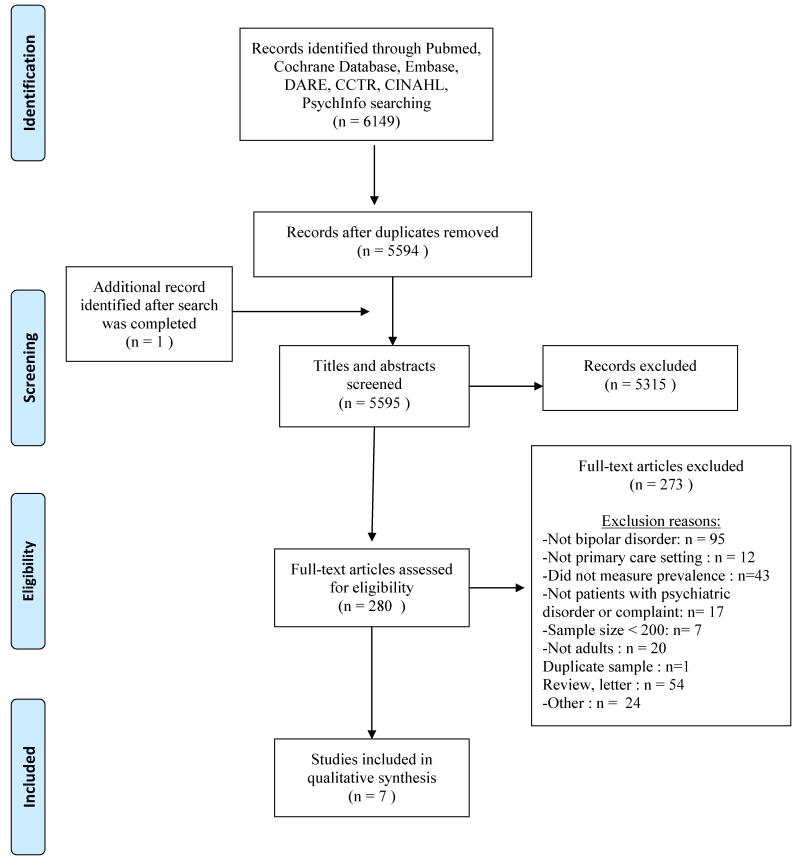

The results of our search are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). We obtained 6147 results, and screened 5595 unique records. The full text of 280 studies was assessed for eligibility. We found seven studies19-25 meeting our inclusion criteria. Bipolar disorder prevalence was measured in primary care patients with depression20-22,24 (n=4 studies), any psychiatric complaint23 (n=1 study), trauma exposure25 (n=1 study), and medically unexplained symptoms19 (n=1study).

Figure 1.

Study identification method: Bipolar disorder prevalence in primary care patients with psychiatric disorder or complaint

The studies in Table 1 are grouped according to whether a screening measure for bipolar disorder was used, or whether bipolar disorder was diagnosed with a structured interview. Two studies19,20 used structured interviews to diagnose bipolar disorder, three studies used screening measures21-23, and two studies24,25 used both a structured interview and a screening measure. Five studies21-25 used the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ)26 screening measure and one study used Hypomania Checklist-32 (HCL-32)27 and the MDQ. The MDQ assesses whether any of 13 symptoms of mania ever occurred concurrently in a patient’s life, if the symptoms were associated with impairment, whether a relative has bipolar disorder, and whether a clinician has ever diagnosed bipolar disorder in the patient. The HCL-3227 assesses whether any of 32 symptoms or behaviors ever occurred concurrently in a patient’s life and whether those symptoms interfered with the patient’s functioning. The investigators22 using the HCL-32 considered a positive screen for bipolar disorder as a score of 14 or more. A prior study has shown that in primary care patients, a score of 18 or more on the HCL-32 has the optimal sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder28. A score of 14 or more likely yielded a higher than usual number of false positive screens. Therefore, the HCL-32 findings from that study22 were not included in our results. Studies using a structured interview and a screening measure permitted the calculation of operating characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value) for the screening measure used compared to the gold standard structured clinical interview, as shown in Table 1. All studies except one22 considered a positive result on the MDQ screen as a score of ≥7 with 2 or more concurrent symptoms resulting in moderate or severe impairment. One study22 defined a positive result as a score of ≥7 only.

Table 1.

Results of screening measures or diagnostic interviews for bipolar disorder in primary care patients with recognized psychiatric disorder or complaint.

| Study | Screening or Diagnostic Measure |

Population and sampling method |

Age and Sex of Study Population |

Psychiatric disorder or problem, and recognition method |

Sample size | Percentage with bipolar disorder on structured interview or a positive bipolar disorder screen |

Standard comparison and operating characteristics |

Misc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Studies

using structured interview (N=2) | ||||||||

| Smith, et al19. 2005. |

CIDI Structured interview |

Patients with medically unexplained symptoms identified through HMO-wide chart review of patients attending 8 or more clinic appointments for 2 consecutive years |

Mean age 47.7 with SD 8.9 years 79.1% Female |

Medically unexplained symptoms Chart review |

N=206 | 3.4% | None | HMO |

| Poutanen O, et al20. 2008 |

CIDI questions and follow-up telephone interview |

Consecutive primary care patients in community health centers |

Mean age 52.2 with SD 11.6 years 49.8% Female |

Depression Diagnosed with Present State Examination |

N = 319 |

4.8% | None | Finland |

|

Studies

using screene r (N=3) | ||||||||

| Smith, et al19. 2005. |

CIDI Structured interview |

Patients with medically unexplained symptoms identified through HMO-wide chart review of patients attending 8 or more clinic appointments for 2 consecutive years |

Mean age 47.7 with SD 8.9 years 79.1% Female |

Medically unexplained symptoms Chart review |

N=206 | 3.4% | None | HMO |

| Poutanen O, et al20. 2008 |

CIDI questions and follow-up telephone interview |

Consecutive primary care patients in community health centers |

Mean age 52.2 with SD 11.6 years 49.8% Female |

Depression Diagnosed with Present State Examination |

N = 319 |

4.8% | None | Finland |

|

Studies

using screene r (N=3) | ||||||||

| Olfson, et al21. 2005 |

MDQ | Random waiting room patients found to have diagnosed major depression, one urban, academic clinic |

75% of sample was over age 45 81.4% Female |

Depression Primary care physician diagnosis |

N=226 |

23.5% (MDQ≥7 with 2 or more concurrent symptoms resulting in moderate or severe impairment) |

None | |

| Kwong MBL, et al22. 2009 |

MDQ | Consecutive patients with past or current diagnosis of depression |

Age Range – 20-65 years old. No mean reported . 1:2 Male to Female ratio |

Depression primary care physician diagnosis |

N=215 |

20.9% (MDQ≥7) |

Hong Kong |

|

| Chiu, et al23. 2011 |

MDQ | Consecutive patients of 54 primary care physicians complaining of current or previous psychiatric symptoms |

Mean age 42.5 with SD 12/2 years 59% Female |

Psychiatric complaint. Prior or current complaint of depression , anxiety, substance use or ADHD |

N=1304 |

MDQ - 27.9% (MDQ≥7 with 2 or more concurrent symptoms resulting in moderate or severe impairment) |

None | Canada |

|

Studies

using structured interview AND screening measure (N=2) | ||||||||

| Hirschfeld, et al24. 2005 |

MDQ SCID |

Consecutive patients receiving antidepressants, one urban, academic clinic |

Mean age 50 (no SD reported ) 81.7% Female |

Depression. Patients receiving antidepressant medication for treatment of depression |

N=649 (649 received MDQ ; 180 received SCID ) |

MDQ - 21.3% (MDQ≥7 with 2 or more concurrent symptoms resulting in moderate or severe impairment ) SCID - 32.8% (Note - Not administered randomly. Given to MDQ + (n=86) and MDQ − (n=94) on almost 1:1 basis ) |

MDQ compared to SCID standard : Sensitivity 58.6% Specificity 86.2% PPV 52.3% NPV 85.1% |

SCID did not measure prevalence in this sample because the SCID sample was weighted towards a sample with almost half MDQ positive patients . |

| Graves, et al25. 2007 |

MDQ (trauma exposure and non-exposure groups) SCID (subsample of trauma exposure group) |

Random waiting room patients found to have either have a history of trauma exposure (n=355) or not have a history of trauma exposure (n=223) from 3 primary care clinics who were enrolled in larger trauma study |

Mean age range from 35- 42.8 years in different diagnostic groups. 66.7% Female |

Trauma exposure. Trauma questionnaire |

N = 578 (578 received MDQ ; 228 received SCID ) |

MDQ(MD Q≥7 with 2 or more concurrent symptoms resulting in moderate or severe impairment ) - Trauma exposure group (n=355) - 30.7% No trauma exposure group (n=223) - 8.5% SCID (given only to subjects with trauma exposure) −9% |

MDQ compared to SCID standard for trauma exposure group : Sensitivity 61.9% Specificity 69.1% PPV 16.8% NPV 94.7% |

|

A. Lifetime prevalence

SCID - Structured Clinical Interview based on DSM IV ; CIDI – Composite International Diagnostic Interview ; MDQ – Mood Disorder Questionnaire ; MINI – Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SD – Standard Deviation

Six studies19-21,23-25 reported the study population’s age with a mean or distribution, and one22 study reported only the age range. Sex was also reported in all studies. This information is presented in Table 1.

Patients with depression

Hirschfeld, et al.24 administered the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ)26 to 649 primary care patients from academic primary care practices receiving antidepressant medications to treat depression. The MDQ was positive in 21.3% of patients. The investigators then administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV)29 to a subsample of patients. The subsample was not randomly selected; rather, 86 patients with a positive MDQ and 94 patients with a negative MDQ received the SCID-IV. They found that 32.8% of the patients who were receiving antidepressants and received the SCID-IV were found to have a structured clinical interview consistent with bipolar disorder.

Poutanen, et al.20 measured the prevalence of bipolar disorder in a sample of 319 primary care patients with depression in community health centers in Finland. This group used two standardized questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)30 structured interview and a follow-up phone interview in those with positive responses to one of the CIDI questions in order to diagnose bipolar disorder, and found that 4.8% of the sample met criteria for bipolar disorder.

As part of a secondary analysis from a large study which screened a random sample of primary care patients in an urban clinic for bipolar disroder31, Olfson, et al.21 examined a subsample (n=226) of patients with depression previously diagnosed by the primary care physician. Almost a quarter (23.5%) of these primarily female, low-income, Hispanic patients in an urban primary care practice, had a positive screen on the MDQ.

In Hong Kong, Kwong, et al.22 found that 20.9% of 218 consecutive primary care patients with depression had a score of 7 or more on the MDQ.

Patients with any psychiatric complaint

Chiu and Chokka23 screened 1304 patients from 54 Canadian primary care practices who presented for any reason to primary care but in the course of the visit reported a current psychiatric complaint or prior psychiatric symptom. They found that 27.9% of patients had a positive screen on the MDQ.

Patients with prior trauma exposure

Graves, et al.25 administered the MDQ to 355 patients with a lifetime exposure to at least one significant trauma and 223 patients without trauma history. A subsample of the 228 patients from the trauma exposure group received the SCID-IV structured interview. The MDQ was positive in 30.4% of the trauma exposure group and 8.5% of the trauma negative group. The SCID-IV structured interview showed that 9% of the subsample of trauma patients had a SCID-IV consistent with bipolar disorder (about one-third of the estimate based on the MDQ).

Patients with medically unexplained symptoms

Smith, et al.19 identified a group of 206 HMO patients with medically unexplained symptoms who had attended 8 or more primary care clinic appointments for 2 consecutive years. The authors conducted a CIDI structured interview on all patients and found that 3.4% of the patients had a CIDI interview consistent with bipolar disorder.

Discussion

In this review of the literature, we found that bipolar disorder was diagnosed in primary care patients with a structured clinical interview in 3.4% of patients with medically unexplained symptoms, 4.8% of patients with depression, and 9% of patients with prior trauma exposure. Positive results on the MDQ screening measure for bipolar disorder were found in 20.9%-23.5% of primary care patients with depression, 27.9% of patients with any psychiatric complaint, and 30.8% of patients with prior trauma exposure.

A lower percentage of patients had bipolar disorder diagnosed on structured clinical interview compared to the percentage of patients with positive results on screening measures. Screening measures for bipolar disorder have been shown to have high false-positive rates31-33. For example, the MDQ has been found to lead to false positive bipolar diagnoses in patients who have post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, impulse control disorders or borderline personality disorder33,34, which likely explains why the study in trauma-exposed primary care patients had the highest percentage of patients with a positive MDQ.

Several of the studies used a two-step case-identification process. Poutanen, et al.20 used two standardized questions from the CIDI and then performed a full structured interview on patients with a positive response to at least one of the two questions. Accurate use of the CIDI involves administering the entire CIDI to patients with a positive response from one of the two screening questions. For bipolar disorder, the CIDI has been shown to have a kappa of 0.94 compared to the SCID-IV, and a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 99.5%, and a positive predictive value of 88.4% in the general population35; and a sensitivity of 74.0-94.8%, a specificity of 97.0-98.8%, and a positive predictive value of 59.1-73.7% in the primary care clinical population36. Therefore the bipolar disorder prevalence of 4.8% from this sample of primary care patients with depression is likely close to the prevalence of bipolar disorder that would have been obtained using the SCID-IV.

The operating characteristics from two studies comparing the MDQ to a structured clinical interview should be interpreted with caution. Hirschfeld, et al.24 administered the MDQ to a random sample of primary care patients with depression, but did not administer the SCID-IV to a random sample of patients with depression. Therefore the operating characteristics of the MDQ from this study (which are higher compared to other studies that have shown lower sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values for the MDQ34,37) likely do not reflect the operating characteristics of the MDQ when used in a random sample of primary care patients with depression. Graves, et al.25 compared the MDQ to the SCID in patients who had trauma exposure only limiting the generalizability of the operating characteristics of the MDQ obtained in that study.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is possible that some studies assessing the prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric complaints were not found in our search. Second, only four studies used structured clinical interviews to diagnose bipolar disorder. Third, studies did not differentiate between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Lack of differentiation between bipolar I and II disorder could lead to delivery of less effective treatment. Fourth, there was substantial heterogeneity across these seven studies, both with respect to study population (i.e. patient characteristics such as sex and age) and setting (i.e., different countries, safety net and academic clinics). Among the studies using patients with depression three different definitions of depression existed, and the non-depression group studies (trauma exposure, medically unexplained symptoms, and any psychiatric complaint) had only one study in each group. Additionally, no study commented on whether the investigators completing the structured interviews or screening measures were blinded to the purposes of the study. Investigators who were un-blinded to the study’s purpose may introduce bias into the assessment of bipolar disorder. Finally, at least one study used different cut-offs for the bipolar screening instrument, making comparison across studies difficult. In the study by Kwong, et al22. the definitions of a positive screens differed from other studies’21-25 definitions likely resulting in a higher percentage of positive screens on the MDQ.

Conclusions and Future Directions

An estimated 3.4 – 9% of primary care patients presenting with depression, trauma exposure, medically unexplained symptoms or other psychiatric complaint have bipolar disorder based on the results of a structured clinical interview. Three to four times as many patients have a positive result on a bipolar disorder screening questionnaire compared to a structured psychiatric interview suggesting that many of these patients have a false positive screen. These findings suggest a limited role for the use of currently available screening measures for bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression or another psychiatric complaint. Future studies should address ways to accurately diagnose bipolar disorder and differentiate between bipolar I and II disorders in primary care patients presenting with depression or anxiety, as these symptoms commonly occur in bipolar disorder and are common complaints in primary care settings. The role of clinician-administered structured interviews such as the CIDI30,35 in accurately diagnosing bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression or anxiety could be examined in future studies. Alternatively, developing a novel screening measure for bipolar disorder intended for use in primary care (based on the characteristics of other well-studied screening measures) settings may be an important next step. Recognizing bipolar disorder in patients presenting with depression or anxiety is important because the course of bipolar disorder and its treatment differs from the course and treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. Antidepressant monotherapy in bipolar disorder may be ineffective and can be associated with increased symptoms of anxiety or bipolar disorder symptoms such as racing thoughts or irritability15,16. Accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder in primary care patients could lead to either primary care based treatment of bipolar disorder or referral to specialty mental health care. Team approaches involving integrated psychiatric and primary care may improve the management of complex primary care patients such as patients with bipolar disorder. Future research could address the optimal treatment for primary care patients with bipolar disorder, and address which patients can be effectively treated in primary care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dimitry S. Davydow MD MPH for his recommendations on search terms and strategies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

Joseph M. Cerimele MD – This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health: 5-T32MH020021-15

Lydia A. Chwastiak MD MPH - None

Sherry Dodson MLS - None

Wayne J. Katon MD – This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health: 5-T32MH020021-15

References

- 1.Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, Fuentes M, Nomura Y, Gameroff M, Weissman MM. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and substance use disorders in an urban general medical practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:876–883. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katon W. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauksch LB, Katon WJ, Russo J, Tucker SM, Walker E, Cameron J. The content of a low-income, uninsured primary care population: including the patient agenda. J Am Board Fam Med. 2003;16:278–289. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.4.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, et al. Validation of the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348–353. doi: 10.1370/afm.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belmaker RH. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:476–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schletter PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schletter PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser J, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning JS, Haykal RF, Connor PD, Akiskal HS. On the nature of depressive and anxious states in a family practice setting: the high prevalence of bipolar II and related disorders in a cohort followed longitudinally. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1997;38:102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Efficacy and safety of long-term fluoxetine versus lithium monotherapy of bipolar II disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-substitution study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:792–800. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidor MM, MacQueen GM. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:156–167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05385gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Ghaemi SH, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Wisniewski S, et al. Adjunctive antidepressant use and symptomatic recovery among bipolar depressed patients with concomitant manic symptoms: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1348–1355. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05122032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. Doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith RC, Gardiner JC, Lyles JS, Sirbu C, Dwamena FC, Hodges A, et al. Exploration of DSM-IV criteria in primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149279.10978.3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poutanen O, Koivisto AM, Matilla A, Joukamaa M, Salokangas RKR. Predicting lifetime mood elevation in primary care patients and psychiatric patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:263–271. doi: 10.1080/08039480801963051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olfson M, Das AK, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky D, Feder A, Gross R, et al. Bipolar depression in a low-income primary care clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2146–2151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong MBL, Mak KY, Law BSO, Sham SK. Preliminary report of a study on the prevalence of bipolar disorders among Chinese adult patietns seen in Hong Kong’s primary care clinics suffering from depressive illness. Hong Kong Practitioner. 2009;31:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu JF, Chokka PR. Prevalence of bipolar disorder symptoms in primary care (ProBiD-PC): a Canadian study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e58–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirschfeld RMA, Cass AR, Holt DCL, Carlson CA. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233–239. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graves RE, Alim TN, Aigbogun N, Chrishon K, Mellman TA, Charney DS, et al. Diagnosing bipolar disorder in trauma exposed primary care patients. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschfeld RMA, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the mood disorder questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873–1875. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angst J, Adolfsson R, Bennazzi F, Gamma A, Hantouche E, Meyer TD, et al. The HCL-32: towards a self-assessment tool for hypomanic symptoms in outpatients. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:217–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Hood K, Craddock N, Simpson SA. Unrecognised bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:49–56. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) NY Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. Doi:10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MH, Pilowsky DJ, Blanco C, Feder A, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2011;185:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder and finding borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1212–1217. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05161yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmerman M. Misuse of the mood disorder questionnaire as a case-finding measure and a critique of the concept of using a screening scale for bipolar disorder in psychiatric practice. Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14:127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Guyer M, Hirschfeld RM, Merikangas KR, et al. Validity of the assessment of bipolar spectrum diosrders in the WHO CIDI 3.0. J Affect Disord. 2006;96:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Calabrese JR, Farley PA, Gruber MJ, Jewell MA, Katon W, et al. Composite International Diagnostic Interview screening scales for DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders. Psychol Med. 2012 doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002334. doi:10.1017/S0033291712002334 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, McGlinchey JB, Dalrymple K, et al. Performance of the mood disorders questionnaire in a psychiatric outpatient setting. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:759–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]