Abstract

Context

Fever is an important sign of inflammation recognized by health care practitioners and family caregivers. However, few empirical data obtained directly from patients exist to support many of the long-standing assumptions about the symptoms of fever. Many of the literature-cited symptoms, including chills, diaphoresis, and malaise, have limited scientific bases, yet they often represent a major justification for antipyretic administration.

Objectives

To describe the patient experience of fever symptoms for the preliminary development of a fever assessment questionnaire.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with 28 inpatients, the majority (86%) with cancer diagnoses, who had a recorded temperature of ≥38°C within approximately 12 hours before the interview. A semi-structured interview guide was used to elicit patient fever experiences. Thematic analyses were conducted by three independent research team members, and the data were verified through two rounds of consensus building.

Results

Eleven themes emerged. The participants reported experiences of feeling cold, weakness, warmth, sweating, nonspecific bodily sensations, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, emotional changes, achiness, respiratory symptoms, and vivid dreams/hallucinations.

Conclusion

Our data not only confirm long-standing symptoms of fever but also suggest new symptoms and a level of variability and complexity not captured by the existing fever literature. Greater knowledge of patients’ fever experiences will guide more accurate assessment of symptoms associated with fever and the impact of antipyretic treatments on patient symptoms in this common condition. Results from this study are contributing to the content validity of a future instrument that will evaluate patient outcomes related to fever interventions.

Keywords: Fever, symptoms, qualitative research, content validity

Introduction

Fever is a universally recognized sign of inflammation, yet the patient-reported symptoms of fever vary across patients, disease types, and disease trajectories. Although the condition has been investigated medically since antiquity,1 today there remains uncertainty associated with fever. This uncertainty stems from the fact that fever is a complex physiological response of which temperature elevation is merely one component.2 One aspect absent from the literature that attempts to elucidate this multifaceted condition is empirical data that link specific patient-reported symptoms to the febrile response.

Most of the in-depth scientific evaluations of fever address the phenomenon only from the perspective of a researcher or clinician. In these studies and medical textbooks, much of what is designated as the symptoms of fever is based on long-standing assumptions about its clinical presentation discussed as a means to explicate the prevailing pathophysiological knowledge of the condition. For instance, chills or rigors are introduced as a manifestation of the process by which the body increases its temperature to the new set point dictated by the production of pyrogenic cytokines.2–4 This discourse serves to associate a widely accepted manifestation of fever, the chills, with the proposed physiology of the condition, the elevation of body temperature by endogenous pyrogens through the stimulation of cytokine release.5 The pathophysiological discussion is grounded by what is considered a ubiquitous symptom. Whether such manifestations are the only or the most bothersome symptoms associated with elevated body temperature has not been validated by nor questioned within the literature.

Because fever is an important sign of inflammation, it is necessary to understand its symptoms and explore the extent to which there are additional factors associated with these symptoms. Some clinicians state that patients “always” have symptoms with elevated body temperature, but neither the type nor frequency of the manifestations has been evaluated. A symptom-focused inquiry is relevant now that evidence suggests physicians are considering the adaptive value of fever and are moving away from reflexive prescriptions of antipyretics.6,7

Antipyretics are pharmaceuticals that reduce the body temperature of febrile individuals without affecting normal or artificially raised body temperatures.8 The administration of antipyretics to children is a common practice supported by most clinicians.7,9 However, some physicians and researchers argue that fever is a benign condition that can serve a protective function and that it should not be justification for the routine administration of antipyretics.1,10,11 Mackowiak argues that no experimental evidence exists to support the most basic justifications of antipyretic administration, specifically that reducing fever via antipyretics eliminates the harmful effects of fever or even that harmful effects necessarily accompany fever.12 Kluger et al.13,14 surmise that fever plays a role in enhancing human specific and nonspecific immunity. Furthermore, Lee et al.15 propose that antipyretic treatments given to suppress the febrile response to infection may worsen patient outcomes. Because antipyretic administration is often justified by a desire to diminish the uncomfortable symptoms of fever,9,12 it is essential that clinicians substantiate the symptoms patients experience during fevers. As Styrt and Sugarman8 explain: “It is frequently acknowledged that a common reason for antipyretic therapy is ‘symptomatic treatment’ of fever. It is less clear exactly what symptoms are being treated and to what extent anti-pyresis actually makes the patient feel better”.(p. 1592)

Currently, there are no valid patient-reported outcome measures to describe the symptoms of fever. Clinical trials of antipyretics often focus on numerical measurements of body temperature only.16 When symptoms have been measured, this has not been comprehensive nor have content-valid standardized measurements been used. This calls into question the validity of these measures. The purpose of this study was to identify and characterize the symptoms of fever to provide content validity for the future development of a quantitative measure.

Methods

Sample

Adult and pediatric medical-surgical patients hospitalized at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center and admitted to the Oncology/Transplant, Surgical Oncology or Pediatrics inpatient units were recruited for this study. This convenience sample included patients at least eight years old who experienced a treated or untreated fever within approximately 12 hours before the interview. For the purposes of this study, fever was defined as a body temperature ≥38°C.

Recruitment Procedures

The clinical nurse specialists and unit charge nurses notified the study team of candidates who fit the eligibility criteria. A member of the research team approached potential participants to provide an overview of the project and obtain informed consent.

Data Collection Procedures

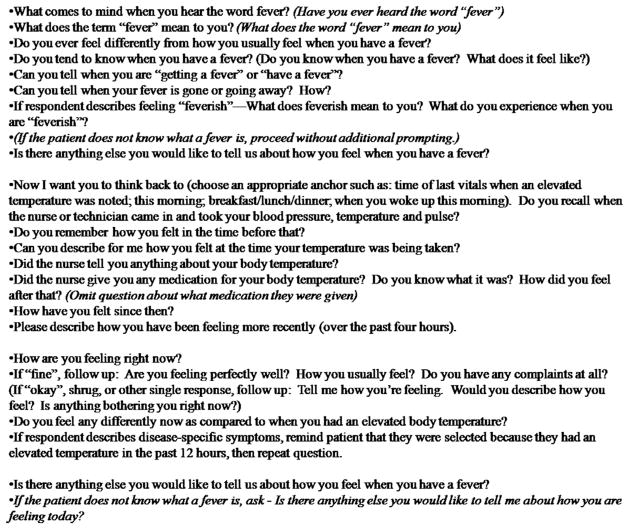

Qualitative, semi-structured, face-to-face elicitation interviews (n = 28) were conducted from February through May 2011 to identify and characterize fever symptoms. A series of open-ended questions were developed to elicit descriptions of the participants’ associations with and conceptualizations of febrile episodes.17 These questions (Fig. 1) queried both the patient’s most recent febrile episode and their past febrile episodes. Questions regarding the patients’ overall perceptions of fever initiated the interview to ensure the data were centered by the notion of fever. Spontaneous and prepared verbal probes were used to explore the bases for responses. The final sample size was determined by reaching data saturation, the advent of four consecutive interviews during which no new symptoms were identified.

Fig. 1.

Elicitation interview guide.

All interviews were conducted in the patients’ hospital rooms to ensure confidentiality. At least two research team members were present at each session. One researcher would lead the interview and the second would take notes to assure no verbal or nonverbal cues from the patient were missed. All sessions were audiotaped. The audiotaped files were then transcribed verbatim. Field notes from both researchers were prepared as written briefs to capture the details of each interview experience.

The research team comprised two clinical nurses (N. J. A., A. R.), one expert in mixed-methods research (G. R. W.), one expert in patient-reported outcomes research (N. K. L.), two statisticians (C. M. -D., M. V.), one infectious disease specialist (J. H. P.), and one research assistant (C. P.).

Data Analysis

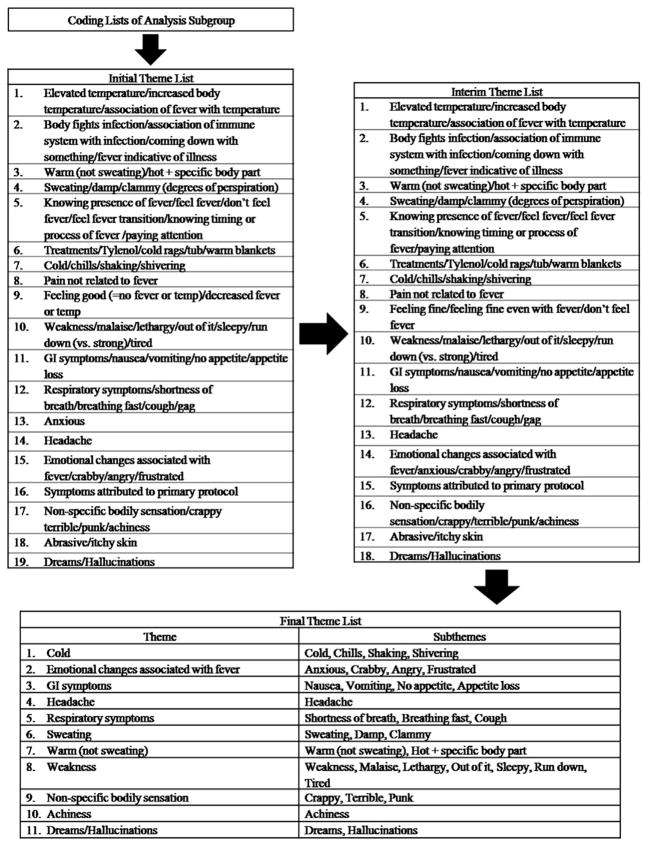

The themes were developed through an iterative process of consensus building among the analysis subgroup (G. R. W., C. M. -D., C. P.), followed by validation among the entire research team. Fig. 2 shows the process through which themes were developed. First, the analysis subgroup conducted independent thematic analyses of all 28 transcribed interviews by categorizing the patient responses based on their content and perceived importance. One of the three members independently constructed an electronic database of the verbatim transcripts and used NVivo (version 7.0, 2006; QSR International Pty., Burlington, MA) to assemble themes and subthemes. Second, one theme list was created by merging the three independent coding lists and by amalgamating overlapping or redundant codes. Similar codes were combined into 19 themes, all of which represented a complete collection of the codes identified by the analysis subgroup; no codes were eliminated to ensure that all data were included in the next stages of analysis. Of the 19 original themes, 18 remained. Third, the entire research team met and assessed a revised patient quotation table generated from the first round of consensus building and further eliminated extraneous themes. This round of consensus building included the input and perceptions of the analysis subgroup and the principal investigator (N. J. A.). During this stage, themes that were determined to lack significance or to be insufficiently related to the phenomenon of fever were eliminated.

Fig. 2.

Process of theme development.

Finally, the analysis subgroup reviewed the NVivo7 database together, generated a table of categorized patient quotations, and refined the initial theme list based on the strength of the themes and the cohesiveness of the sub-themes. Inclusive, descriptive labels for the 11 remaining themes also were assigned at this time. The final 11 themes and subthemes are listed in Fig. 2.

Methodological Rigor

Throughout the qualitative data collection and analysis process, we worked to achieve the four criteria that comprise the standards of rigor for qualitative research: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability.18 Credibility was maintained by the three independent analyses of our transcribed interview data, which ensured that our theme categories covered all relevant data, and the three rounds of consensus building, which ensured that similarities within and differences between our theme categories were evaluated thoroughly. Dependability was established through data collection by maintaining interviewer consistency across all interviews and through data analysis by our recurrent team reviews of the study data. Confirmability was supported by developing an electronic, thematic database and through the preservation of interviewer perceptions via interview field notes. Transferability was made possible through our diverse study team comprising individuals with various clinical and research-related expertise. Transferability is also demonstrated through our presentation of illustrative patient quotations that represent our final theme categories.

Protection of Human Subjects

The National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants provided informed consent for a 15–20 minute interview. In the case of a research participant younger than 18 years, assent was obtained from the child and consent was obtained from their parent or legal guardian. No compensation was offered to the study participants.

Results

Participant Demographics

Of the 45 individuals approached for consent, 28 agreed to participate and were consented. A common reason given for those who did not participate was discomfort and/or the severity of their disease symptoms at the time of the interview. Participant ages ranged from 15 to 69 years (mean = 47; SD = 15). Ten participants (36%) were female; four (14%) were non-Hispanic black/African American and the remaining 24 (86%) were non-Hispanic white. The majority (86%) had cancer diagnoses. All participants experienced a body temperature ≥38°C within approximately 12 hours before the interview, ranging from 38.0°C to 40.6°C. The interviews ranged in length from three minutes and 15 seconds to 17 minutes and 54 seconds. Table 1 presents the participant demographics. The diversity of the sample, including a range of ages and a variety of diagnoses, assured that the signs and symptoms elicited would be representational as our purpose was to develop an assessment tool that would be valid in many clinical settings.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (64) |

| Female | 10 (36) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Metastatic melanoma | 8 (29) |

| Renal carcinoma | 2 (7) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 (7) |

| Adrenal cell carcinoma | 1 (3.5) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (3.5) |

| Synovial sarcoma | 1 (3.5) |

| Carcinoid syndrome | 1 (3.5) |

| Thyroid cancer | 1 (3.5) |

| Leukemia | 1 (3.5) |

| Secondary myelofibrosis | 1 (3.5) |

| Adult T-cell lymphoma and leukemia | 1 (3.5) |

| Marginal zone lymphoma | 1 (3.5) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 1 (3.5) |

| Refractory follicular lymphoma | 1 (3.5) |

| Cervical cancer | 1 (3.5) |

| Von-Hippel Lindau disease | 1 (3.5) |

| X-linked combined severe immunodeficiency | 1 (3.5) |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 (3.5) |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | 1 (3.5) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47 (15) |

| Reference episode temperature,a mean (SD) | 38.5 (0.7) |

| Highest temperature, mean (SD) | 38.6 (0.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 28 (100) |

| Race | |

| White | 24 (86) |

| Black/African American | 4 (14) |

The reference episode temperature is the temperature, necessarily ≥38 C, that qualified patients for the study. The highest temperature is the reference episode temperature or any temperature 12 hours prior that was higher.

Interview Themes

Eleven themes emerged from the interviews. These themes, the symptoms they include, and illustrative patient quotations are displayed in Table 2. The frequency of each theme throughout the 28 interviews is represented in the rightmost column of Table 3.

Table 2.

Qualitative Themes and Illustrative Patient Quotations

| Themea | Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Cold (cold, chills, shivering, shaking) | “Felt cold and shivery.” “I will have really bad chills and I’ll be shivering—I can’t stop shivering.” |

| Weakness (weakness, malaise, lethargy, out of it, sleepy, tired, run-down) | “Elevated body temperature and usually some general weakness.” “Don’t know why—I just felt tired.” |

| Warm (not sweating) (warm, hot body part) | “I was feeling feverish. My head and my ears were hot. I was feeling warmer.” “Yes, I really feel warm. I take my temperature and it’s up.” |

| Sweating (sweating, damp, clammy, degrees of perspiration) | “Most recently, I got chills horribly. The time before that, I just got really warm and clammy.” “My body just feels cold and I sweat quite a bit.” |

| Nonspecific bodily sensation (crabby, terrible, punk) | “Yes, like something, like a little bit like right before your temperature goes up, you feel crappy, you get like a weird feeling.” “I felt terrible.” |

| GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, appetite loss) | “She asked me how I was feeling, I think. And I was feeling a little bit nauseous.” “With the fever, I don’t feel like eating.” |

| Headache | “And sometimes, like, for example, right now, I would get headaches with my fevers.” “You get a splitting headache.” |

| Emotional changes associated with fever (anxious, crabby, angry, frustrated) | “Like I said, I think fever is really tied in to how you feel emotionally. Because I know every time I have a fever, I just get snotty, for lack of a better term, because I’m just really agitated.” “I feel tired. I feel irritable.” |

| Achiness | “My body starts aching. My whole body starts aching at my joints. It doesn’t really happen that often, but when it does I can more or less tell when I am coming down with something.” “You have achiness, pains, nausea.” |

| Respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, breathing fast, cough) | “And I had some breath problems. I felt that I don’t breathe normal.” “Trouble breathing.” |

| Dreams/hallucinations (dreams, hallucinations) | “And like I said, I sleep fitfully and I keep having these dreams, which were strange, which I kind of thought maybe was caused by the drugs taken for the pain, but I haven’t taken that many.” “Yes. I had that dream, like I said, as a kid, probably until the time I was 16 or 17 years old. I still remember. And only when I had a fever.” |

GI = gastrointestinal.

The descriptive label for each theme is listed in the “Theme” column as the word or phrase outside of the parentheses. The symptoms included within each label are listed within the parentheses.

Table 3.

Data Saturation Matrixa

| Fever Symptoms | Participants

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | n | |

| Cold | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 22 | ||||||

| Weakness | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 22 | ||||||

| Warm | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 21 | |||||||

| Sweating | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 18 | ||||||||||

| Nonspecific bodily sensation | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GI symptoms | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Headache | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emotional changes associated with fever | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achiness | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory symptoms | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dreams | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

GI = gastrointestinal.

The letter “x” is used within the grid to denote that the corresponding patient expressed the corresponding theme during the interview. Saturation, the advent of four interviews during which no new themes are expressed, occurred after the interview of Patient 20. The remaining eight interviews were conducted to validate saturation and to ensure credibility.

Cold

Twenty-two of the 28 interviewees (79%) expressed that they felt cold, had the chills, shivered, or shook while experiencing a fever. Some study participants related feeling cold to a specific stage of the febrile process. “I think just before you get the fever you can tell. You get the chills, everything feels colder than it should, so you know something is changing with your body temperature,” one participant remarked. A few participants associated the sensation with a particular febrile magnitude: “Yes, I didn’t feel like I was having chills. Once you get to a certain point maybe that’s when the chills start kicking in.”

Weakness

Notwithstanding cold, weakness was the most frequently expressed theme (n = 22; 79%). For one participant, weakness was the only symptom he experienced during his most recent febrile episode. “Yes [I felt] very sleepy. I didn’t know there was a problem. She just said you have a high temperature or a temperature, I would have gone, oh, there is something wrong with me. I didn’t know that.”

Warm (Not Sweating)

Twenty-one participants (75%) associated fevers with feeling warm. As with feeling cold, some participants were able to note at which points during a febrile episode they felt warm. “I have been having like these weird like fevers lately where I will get really hot and then a couple hours goes by and I’ll just break out in a hard sweat.” As exemplified by this participant’s response, warmness sometimes was related to sweating.

Sweating

Study participants (n = 18; 64%) used various terms such as “clammy” and “damp” to convey that they experience some degree of perspiration during fevers. Some participants related sweating to the final stages of a fever, when a fever “breaks.” “Yes, you can tell when a fever breaks,” one patient said, “I tend to sweat a lot.”

Nonspecific Bodily Sensation

More than one-third of the patients (n = 11; 39%) reported experiencing a general bodily sensation that was a noticeable deviation from the norm. This notion differed from achiness and was expressed using words such as “crappy,” “terrible,” and even “punk.” One participant explained: “I feel off-kilter. I just do not feel perfect.”

Gastrointestinal (GI) Symptoms

Nine participants (32%) linked fevers with GI symptoms, the most common of which was nausea. When asked how he usually feels during a fever, one participant responded: “Generally lethargic and, depending on how many degrees above normal, sometimes physically nauseated and a headache.”

Headache

The theme headache was captured both within the participants’ general associations with fever, “You get a headache, I usually have a headache,” and within the participants’ evaluations of their current conditions, “But I know right now, I just have a headache and I’m tired.” Nine interviews (32%) contained such expressions.

Emotional Changes Associated With Fever

The emotional changes that five participants (18%) associated with febrile episodes included “anxious,” “crabby,” “frustrated,” as well as a general feeling of heightened emotions. One participant stated that a “kind of agitated” feeling accompanied his febrile weakness.

Achiness

Three participants (11%) experienced body aches during fevers. All three associated the symptom generally with fevers but two also put forward that achiness is one symptom that can alert them to their elevated body temperatures.

Respiratory Symptoms

Three participants (11%) mentioned that respiratory symptoms accompany their fevers. These symptoms included shortness of breath, trouble breathing, and coughing.

Dreams/Hallucinations

In total, three participants (11%) expressed that they experience dreams or hallucinations during fevers. The two participants who noted experiencing odd dreams during fevers described these dreams in a detailed manner. One stated that his “fever dream” involved a series of instances that would move “back and forth between a very difficult circumstance and a very comfortable circumstance.” The other explained that he dubbed his dreams “a New York state of mind” because: “I’m just talking to people whose faces I see in the crowd, and they say something and I say something, and it’s usually smart alecky and it’s kind of like that. But at the time that you’re doing it, it seems like it’s really deep, but I couldn’t tell you what those things were that were said afterwards, if I had to.”

We examined the three least commonly expressed symptoms (dreams, respiratory symptoms, and achiness) to determine if these symptoms were recalled by a particular patient subgroup such as patients of a particular diagnosis or patients who received interleukin 2 (IL-2) as a component of their clinical care (IL-2 is a treatment known to induce flu-like symptoms). Clearly, a limitation of this sort of analysis is the small sample size. However, the three least commonly expressed symptoms had no visible correlation with any specific diagnosis or with the administration of IL-2. As further analysis, we divided the sample into surgical and medical patients to determine if differences exist in their fever symptomatology. We examined all 11 symptoms for a discernible pattern that discriminated the two subgroups. Again, there was no discernible difference between those patients who had surgery during their admission and those who did not.

Discussion

Our study participants articulated that during fevers they experience some of the commonly cited symptoms including cold, warmness, sweating, and weakness. However, their febrile experiences were not limited to these symptoms; they also report less frequently addressed manifestations including nonspecific bodily sensations, GI symptoms, headaches, emotional changes associated with fever, achiness, respiratory symptoms, and dreams/hallucinations. These early findings suggest that fever produces a unique and distinct constellation of symptom experiences for patients. This fact has not been documented nor studied previously.

That “cold” was one of the two most frequently expressed fever symptoms corresponds to the literature regarding the pathophysiology of elevated body temperature. This sensation may be indicative of a cytokine induced “resetting of the hypothalamic set point” and a corresponding elevation in body temperature until this new set point is reached.3 The inception of temperature elevation manifests in the febrile individual as “symptoms such as chilliness and sometimes frank shaking chills” because chills are a mechanism of bodily heat production.3 According to one text, “Clinicians have observed patients with febrile illness who complain of cold before the onset of fever”3.(p. 437) Our qualitative results support this claim, as some of the 22 participants who reported feeling cold during fevers related the sensation to the beginning of the febrile process.

Knochel et al. also state that warmness and then sweating follow the cold feeling that begins the fever process.3 The greater proportion of our study participants experienced these respective symptoms, and some participants who experienced sweating did indeed associate the symptom with the final stages of the fever. However, our results diverge from the extrapolation that “the triad of cool sensation followed by warmth and then sweating is almost always present in true fever (i.e., elevations in body temperature mediated by endogenous pyrogen)”3 (p. 437). Although a majority of our participants reported experiencing these three symptoms, this statement implies that the 36% of participants (n = 10) who did not report experiencing perspiration, for example, likely did not experience a “true” fever. Our results instead reveal a range of symptoms that vary among patients, suggesting that the symptoms of fever cannot be reduced so easily.

In addition to “cold,” “warm,” and “sweating,” we found “weakness” to be a commonly expressed fever symptom. This result is consistent with the association of fever with malaise.4,19 This result also is consistent with the finding that weakness is a common “accompanying trouble” of febrile episodes.20 In the Oborilová et al.20 study, “total unwell and weakness” was the second most frequently chosen “accompanying trouble,” differing from the most frequently chosen symptom by 2%. Their double-barreled response option, however, obscured which respondents experienced just “weakness” or both “weakness” and “total unwell.” Therefore, it is possible that the inclusion of “total unwell” in the question affected the response rate of participants who experienced “weakness” during fevers.

The remaining seven fever symptoms were communicated less consistently by our study sample, yet they still represent meaningful manifestations of the febrile process (Table 3). All were expressed clearly and with a substantial degree of confidence, verbal qualities that give un-quantifiable thematic strength. More data on the prevalence of these symptoms within a wider distribution of recently febrile individuals are necessary to evaluate further their significance.

The 11 themes found in this study will provide content for the future development of a quantitative patient-reported outcome measure that will further explicate the epidemiology of the fever symptoms and the impact of interventions on outcomes.

Limitations

Our sample included predominately individuals with cancer diagnoses but cancer diagnosis was not an inclusion criterion for our study as we are attempting to develop a tool that could be used in adult medical-surgical patients to assess fever symptoms. As a component of their clinical care, some participants received biotherapy treatments including high-dose intravenous IL-2, a treatment known to induce flu-like symptoms. The acute conditions of some participants, in addition to their potentially fever-generating treatments, represent a limitation of this study. It is possible that their underlying condition and treatment brought about symptoms that differ from the most common manifestations of fever.

Another limitation of this study is that some of the participants were given antipyretics or other medications during their most recent fever. This may have affected the way they experienced that particular fever episode. However, participants also were asked to evaluate their experiences with fever in general in an attempt to offset such variability. Other limitations are attention and recall, that perhaps our study participants did not relate less readily apparent or memorable symptoms. There is no way to predict, and therefore offset, this limitation within our sample; however, interviewing patients approximately 12 hours after a fever limits this bias.

Conclusions

Fever is an important sign of infection. In some clinical presentations of fever, for example, the neutropenic patient, fever is the only sign of infection. Clinicians would benefit from a valid and reliable fever assessment instrument. This work serves as a foundation for the development of a patient-reported outcome instrument that will evaluate fever symptoms. Our study was performed in patients predominately with cancer diagnoses and will need further evaluation in a general medical-surgical population. The next step is to develop preliminary items for cognitive interview testing, which will assess the completeness and understandability of the themes identified in this formative phase. The instrument developed will evaluate the epidemiology of fever symptoms and will examine the frequency and duration of these symptoms. The tool will be tested in a larger sample to validate the signs and symptoms reported here. The site of this next phase will be the NIH Clinical Center. In addition, we would encourage testing this tool across other hospitals that have more representative medical-surgical patient populations. This research supports some of the long-standing assumptions regarding the clinical presentation of fevers, suggests a more complex and variable perspective of the condition, and provides a foundation for further investigation into fever symptoms. It is surprising that despite the pervasiveness of the condition, its extensive use as an outcome in clinical investigations, and its own status as an important sign of inflammation, there has been so little research concerning the relationship between elevated temperatures and patient-reported symptoms. Greater knowledge of fevers will guide more accurate assessments of the epidemiology of fever symptoms. This research also may inform future clinical trials regarding the impact of antipyretic therapies on patient symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. This research also was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SAIC funding statements: This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH, under Contract No. HHSN2612008 00001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Blumenthal I. Fever—concepts old and new. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:391–394. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackowiak PA. Fever. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious disease. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 703–718. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knochel JP, Goodman EL. Heat stroke and other forms of hyperthermia: elevations in body temperature not mediated by endogenous pyrogens. In: Mackowiak PA, editor. Fever: basic mechanisms and management. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 437–457. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogoina D. Fever, fever patterns and diseases called ‘fever’—a review. J Infect Public Health. 2011;4:108–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nogare ARD, Sharma S. Exogenous pyrogens. In: Mackowaik PA, editor. Fever: basic mechanisms and management. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travers B. Fever. In: Blanchfield DS, Long JL, editors. The Gale encyclopedia of medicine. 2. Detroit, MI: Gale; 2002. pp. 1313–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan JE, Farrar HC. Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:580–587. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Styrt B, Sugarman B. Antipyresis and fever. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1589–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker J, Wu S. Fever—an update. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100:281–290. doi: 10.7547/1000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eyers S, Weatherall M, Shirtcliffe P, Perrin K, Beasley R. The effect on mortality of antipyretics in the treatment of influenza infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:403–411. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.090441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandts CH, Ndjav M, Graninger W, Kremsner PG. Effect of paracetamol on parasite clearance time in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1997;350:704–709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackowiak PA. The febrile patient: diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic considerations. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2297–2301. doi: 10.2741/1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kluger MJ, Kozak W, Conn C, Leon L, Soszynski D. The adaptive value of fever. In: Mackowaik PA, editor. Fever: basic mechanisms and management. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluger MJ. Fever. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee BH, Inui D, Suh GY, et al. Association of body temperature and antipyretic treatments with mortality of critically ill patients with and without sepsis: multi-centered prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R33. doi: 10.1186/cc11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A. Paracetamol for treating fever in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD003676. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starks H, Trinidad S. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodward TE. The fever pattern as a diagnostic aid. In: Mackowiak PA, editor. Fever: basic mechanisms and management. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oborilová A, Mayer J, Pospísil Z, Korístek Z. Symptomatic intravenous antipyretic therapy: efficacy of metamizol, diclofenac, and propacetamol. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]