Abstract

Nα-terminal acetylation of peptides plays an important biological role but is rarely observed in prokaryotes. Nα-terminal acetylated thymosin α1 (Tα1), a 28-amino-acid peptide, is an immune modifier that has been used in the clinic to treat hepatitis B and C virus (HBV/HCV) infections. We previously documented Nα-terminal acetylation of recombinant prothymosin α (ProTα) in E. coli. Here we present a method for production of Nα-acetylated Tα1 from recombinant ProTα. The recombinant ProTα was cleaved by human legumain expressed in Pichia pastoris to release Tα1 in vitro. The Nα-acetylated Tα1 peptide was subsequently purified by reverse phase and cation exchange chromatography. Mass spectrometry indicated that the molecular mass of recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was 3108.79 in, which is identical to the mass of Nα-acetylated Tα1 produced by total chemical synthesis. This mass corresponded to the nonacetylated Tα1 mass with a 42 Da increment. The retention time of recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 and chemosynthetic Nα-acetylated Tα1 were both 15.4 min in RP-high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). These data support the use of an E. coli expression system for the production of recombinant human Nα-acetylated Tα1 and also will provide the basis for the preparation of recombinant acetylated peptides in E. coli.

1. Introduction

Protein acetylation is a common posttranslational modification in eukaryotes but is rarely found in prokaryotes [1–4]. Acetylation has been suggested to play an important biological role in modulating enzymatic activity, protein stability, DNA binding, and peptide-receptor recognition [1]. Charbaut proposed that neutralization of the amino-terminal (N-terminal) positive charge by Nα-acetylation may influence specific interactions with protein partners [3]. For example, nonacetylated rat glycine M-methyltransferase does not exhibit the cooperative behavior of its native counterpart [5]. Acetylation can also affect protein stability. The half-life of nonacetylated-MSH (α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone) in rabbit plasma appears to be one-third of that of the acetylated form [6].

Although acetylation is not as common in prokaryotes as in eukaryotes, researchers have identified acetylated forms of recombinant peptides and proteins to be expressed in E. coli, examples include interferon α and γ [7, 8], somatotropin [9], interleukin-10 [10], and chemokine RANTES S24F [11]. However, some of these proteins or peptides, such as interferon α and γ, are not known to be acetylated in their native forms. Thus, the acetylated forms of these proteins are of little clinical utility.

Thymosin α1 (Tα1) is an immune modifier that has been shown to trigger maturational events in lymphocytes; affect immunoregulatory T-cell function; promote IFN-α, IL-2, and IL-3 production by normal human lymphocytes; and increase lymphocyte IL-2 receptor expression [12]. Tα1 is a 28-amino-acid polypeptide that was originally isolated from thymosin fraction 5. The active peptide, which contains an Nα-terminal acetylated serine residue, is cleaved from prothymosin α (ProTα) by legumain, a lysosomal asparagine endopeptidase (AEP) in mammals [13]. Given the immunomodulatory properties of Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1, it is currently being developed for treating several diseases, including hepatitis B and C virus (HBV/HCV) infections, nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), hepatocellular carcinoma, AIDS, and malignant melanoma [14–18].

To date, Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 has been produced by total chemical synthesis for clinical use. However, with 28 residues, it is expensive to produce the peptide by chemical synthesis. As an alternative to synthesis, prokaryotic expression systems are widely used for producing large quantities of recombinant proteins or peptides. When prothymosin α (ProTα) and its Nα-terminal peptide, Tα1, were identified 20 years ago, no acetylation was found when they were expressed in E. coli [19, 20]. Other groups have expressed recombinant Tα1 as a fusion protein or in concatemer form in E. coli [21–24].

We have previously reported that a fraction of recombinant human ProTα is Nα-terminal acetylated when expressed in E. coli [4]. In this study, we expand on this observation and describe a new method for production and purification of Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 from E. coli. This method may provide a useful alternative to chemical synthesis for producing acetylated peptides for clinical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmids and Strains

The human ProTα expression plasmid pBV220-proTα was constructed previously [4]. The yeast Pichia pastoris expression plasmid pPIC9, which contains the promoter of the methanol-inducible P. pastoris alcohol oxidase 1 (AOX1) gene, the α-mating factor prepro secretion signal from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the HIS4 auxotrophic selection marker, was purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA, USA). The P. pastoris GS115 (his4) host strain was from Invitrogen. HepG2 liver carcinoma cell line was purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell biology (Shanghai, CAS, China).

2.2. Production and Purification of Recombinant Human Prothymosin α in E. coli

Recombinant human Nα-acetylated ProTα was produced as described previously [4] with some modification. The ProTα gene was cloned in plasmid pBV220, with expression under control of the PLPR promoter. Expression of ProTα was induced by increasing the culture temperature from 30°C to 42°C for 6 h. After induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation.

The cells were suspended in buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) and incubated at 85°C for 15 min. Acetic acid was added to adjust the pH to 4.0 and to precipitate E. coli proteins. Precipitated proteins were spun down, and the supernatant containing ProTα was applied on a DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column (Ø1.6 × 20 cm, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with buffer A. After washing, the bound protein was eluted with a gradient from 0 to 0.4 M NaCl. Since ProTα does not contain any aromatic residues, elution of ProTα was monitored by UV absorption at 214 nm. The level of protein and nucleic acid contamination was estimated by UV absorption at 280 nm [25]. The purity of the ProTα in eluate fractions was analyzed by 18% SDS-PAGE.

2.3. Cloning, Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human Prolegumain in Pichia pastoris

Total mRNA was isolated from HepG2 cell line and converted to single-stranded cDNA using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase as described by the manufacturer (TIANGEN BIOTECH Co., Beijing, China). The human legumain gene without signal peptide was amplified by PCR using forward primer legu4 (5′-AGACTCGAGAAAAGAGTTCCTATAGATGATCCTGAAG-3′) and reverse primer legu5 (5′-TATGCGGCCGCTTAGTAGTGACCAAGGCACACGTG-3′); primers were designed based on the ORF of legumain reported previously [26]. Amplification reactions were performed with Pyrobest polymerase (TaKaRa BIOTECH Co., Dalian, China) at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were cloned into the XhoI and NotI sites (both underlined in primers) of Pichia pastoris expression vector pPIC9 to generate the legumain expression vector pPIC9-legumain. The sequence of legumain was verified by sequencing.

Recombinant prolegumain was expressed in P. pastoris following the protocol for scale-up expression in shaker flasks as described in the P. pastoris expression manual (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The pPIC9-legumain expression vector (10 μg) was digested with SalI. P. pastoris GS115 host strain was transfected with the linearized vector by electroporation at 1.5 kV, 129 Ω, and 25 μF in electroporation cuvettes (2 mm gap; BTX). P. pastoris colonies growing on MD plates (1.4% yeast nitrogen base, 2% dextrose, 4 × 10−5% biotin, and 1.5% agar) were picked for expansion in 50 mL of yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium (YPD) consisting of 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose. Expression of the recombinant legumain was induced by culturing P. pastoris in methanol-complex medium containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, 1.34% yeast nitrogen base, 4 × 10−5% biotin, and 0.5% methanol. Cultures were grown for 72 h, and 0.5% methanol was added every 12 h.

Culture supernatant containing prolegumain was diluted with 5 volumes of buffer C (20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5) and applied to SP Fast flow column (Ø1.0 × 16 mm, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After washing with buffer C, bound protein was eluted with a step gradient of 25%, 45%, and 100% buffer D (20 mM sodium acetate, 1 M NaCl, and pH 5.5). Eluate fractions were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing recombinant prolegumain were dispensed into aliquots and stored at −70°C until use.

2.4. Autoactivation of Recombinant Human Legumain

To determine the optimum time for autocatalytic activation, 500 μL aliquots of the recombinant prolegumain (0.2 mg/mL) were incubated in 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 4.0. Samples were incubated for 0 h, 0.25 h, 1 h, and 4 h at 37°C. Digest products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) and stained with Coomassie Blue.

2.5. Cleavage of ProTα by Recombinant Human Legumain In Vitro

To optimize digestion of ProTα by recombinant autoactivated legumain, 250 μL aliquots of recombinant ProTα (2 mg/mL) were mixed with 50 μL of legumain in buffer containing 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 4.0). Samples were incubated for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 16 h at 37°C. Digest products were assayed by SDS-PAGE (18%) and stained with Coomassie Blue.

2.6. Purification of Nα-Terminal Acetylated Tα1

Purified ProTα (100 mg) was cleaved by autoactivated legumain (1 mg) for 8 h at 37°C. The pH was adjusted to 3.0 by addition of acetic acid. The sample was applied to a PoRos R50 column (Ø1.6 × 20 mm, ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) equilibrated with buffer E (1 M NaCl, 0.1% HCl), and washed with two bed volumes of buffer F (1% ethanol, 0.1% HCl). Protein was eluted with a step gradient of 10%, 20%, and 30% ethanol. Eluate fractions were assayed by RP-HPLC.

Tα1-containing fractions were loaded onto an SP High performance column (Ø1.6 × 20 mm, ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) and washed with equilibration buffer M (10 mM NaCl). Bound protein was eluted with 0.2 M NaCl, 0.3 M NaCl, and 0.5 M NaCl. Eluate fractions were assayed by reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.7. RP-HPLC Analysis of Nα-Terminal Acetylated Tα1

RP-HPLC was performed using the HP HPLC 1090 system. A C18 column (5 μm, Ø4.6 × 250 mm, Johnson Technologies Co. Dalian, China) was equilibrated at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min in solvent A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water). Solvent B was 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile. Samples (25 μL) were injected on the column, and peptides were eluted with a linear solvent gradient (100% A : 0% B to 85% A : 15% B for 5 min; 85% A : 15% B to 75% A : 25% B for 15 min; 75% A : 25% B to 0% A : 100% B for 5 min). Peptide elution was detected by UV-absorption at 214 nm. The column was reequilibrated with solvent A for 20 min between runs.

2.8. Mass Spectrometry Characterization and Sequencing of Nα-Terminal Acetylated Tα1

Purified Tα1 samples were desalted on a C18 Zip-Tip column (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and eluted in methanol, water, and acetic acid (50 : 50 : 0.5). The molecular mass of Nα-acetylated Tα1 was determined by nanoelectrospray ionization (nanoESI) quadrupole time-of-fight (Q-TOF MS) using a Q-TOF2 mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK). The peptide sequence was determined by tandem mass spectrometry.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Purification of Recombinant Prothymosin α Expressed in E. coli

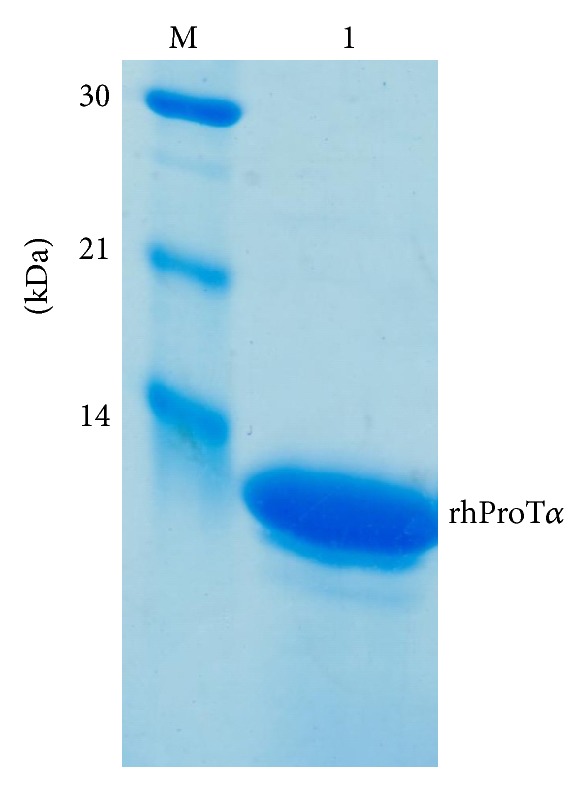

Recombinant human prothymosin α was overexpressed in E. coli [4] and purified by thermal denaturation and anion exchange chromatography. Purified protein appeared as a single homogeneous band with a molecular mass of 12 kDa in 18% SDS-PAGE (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE of recombinant human prothymosin α produced by E. coli. The purified recombinant human prothymosin α was separated with 18% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue G-250. Molecular weight markers were loaded in the same gel (lane M).

3.2. Preparation of Recombinant Legumain in Pichia pastoris and Autoactivation

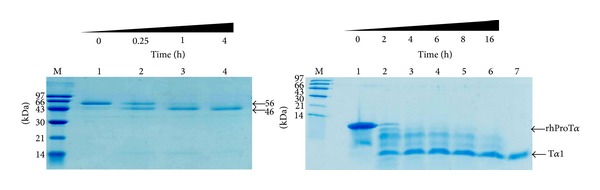

We overexpressed human legumain proenzyme, which is reported to cleave ProTα at asparaginyl-glycine sites and release peptide products Tα1 and Tα11, in Pichia pastoris, and purified it by cation exchange chromatography. The molecular mass of recombinant prolegumain was 56 kDa. When incubated at an acidic pH, the recombinant proenzyme was autocleavaged to a 46 kDa form in a time dependent manner (Figure 2(a), lane 2–4).

Figure 2.

(a) Expression and purification of legumain in P. pastoris and its autoactivation. SDS-PAGE of autocatalytic legumain after the prolegumain was incubated in buffer as a function of time (0–4 h) at 37°C. Aliquots of each reaction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) and stained with Coomassie blue. Each time point is marked on the bottom of its corresponding lane. (b) SDS-PAGE analysis of Prothymosin α proteolysis by recombinant legumain in vitro. Aliquots of ProTα were incubated with recombinant legumain at 37°C in buffer containing 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 4.0). Each reaction mixture was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under the conditions indicated under “Experimental Section.” Each time point is marked on the bottom of its corresponding lane 1–6. Lane 7 is the chemically synthesized Nα-acetylated Tα1.

3.3. Prothymosin α is Processed to Thymosin α1 by Recombinant Legumain In Vitro

To process ProTα by recombinant legumain in vitro, we systematically studied the proteolysis of ProTα as a function of pH, temperature, time, and amount of legumain. After incubation with the autoactivated legumain, the band corresponding to ProTα decreased in intensity and a band with similar molecular mass of Tα1 increased in intensity in a time-dependent manner. When 500 μg ProTα was incubated with 10 μg legumain, the majority of ProTα was cleaved in 2 h, and the cleavage was complete in 6–8 h (Figure 2(b), lane 4-5). Decreasing the amount of legumain also resulted in complete cleavage but required longer incubation times (data not shown).

Legumains have previously been extracted from mammalian and plant cells and tissues [13, 27, 28]. However, these preparations typically have low concentrations and are easily contaminated by other enzymes. This study established a method with which to overexpress the recombinant enzyme in yeast and confirmed its activity in the enzymatic processing of ProTα. The yeast expression system is easy and economical to grow on a large scale, and it has been used as an efficient system for production of heterologous proteins [29, 30]. The recombinant prolegumain (56 kDa) incubated at an acidic pH was autocleavaged to a 46 kDa form. This result is consistent with reports that the 56 kDa proenzyme cleaves off the C-terminal 110 residues to form the 46 kDa active enzyme [13].

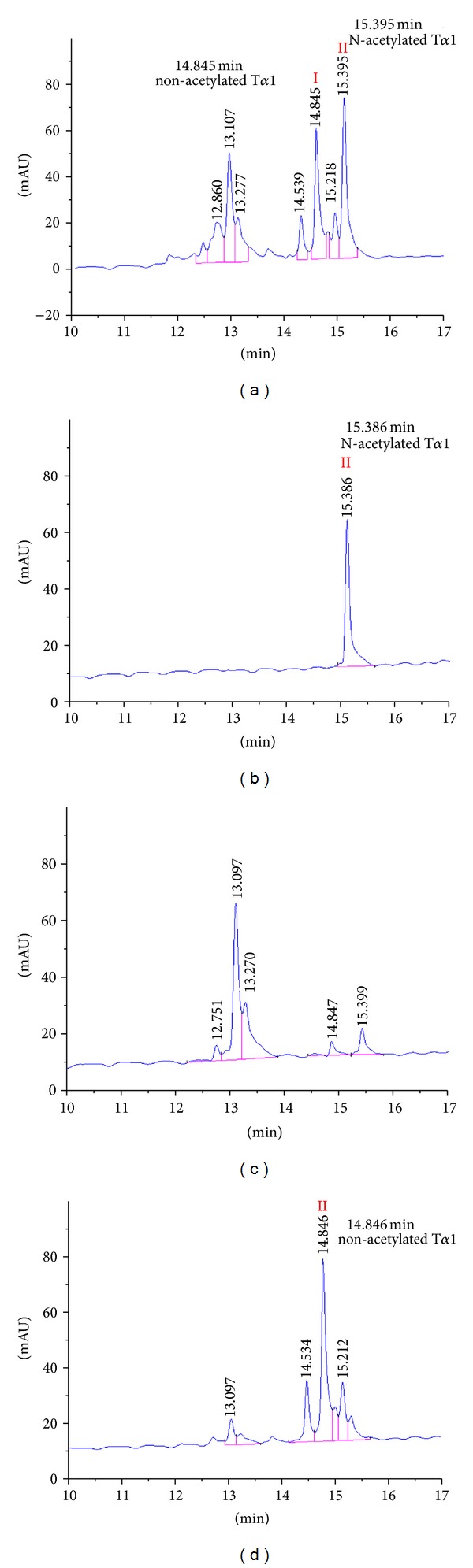

3.4. Purification of the Nα-Terminal Acetylated Thymosin α1

To purify the Nα-acetylated Tα1 from the ProTα cleavage products, the proteolytic products were separated by RP chromatography in PoRos R50 media. Peptide fractions eluted with 10%, 20%, and 30% ethanol were assayed by RP-HPLC, and Nα-acetylated Tα1 (Figure 3(a), peak II) and nonacetylated Tα1 (Figure 3(a), peak I) were both identified in 20% ethanol fractions. The acetylated and nonacetylated forms were further separated by cation exchange chromatography. The Nα-acetylated Tα1 eluted as a single peak (as monitored by UV absorption at 214 nm) in the 0.2 M NaCl elution fraction (Figure 3(b), peak II). Other peptides were found in 0.3 M NaCl and 0.5 M NaCl eluted fractions, including the nonacetylated Tα1 that eluted with 0.5 M NaCl (Figure 3(d), peak I). Thus, the Nα-acetylated and nonacetylated forms of Tα1 were completely separated by cation exchange chromatography.

Figure 3.

RP-HPLC analysis of Nα-acetylated Tα1. (a) Sample purified by PoRos R50 column was analyzed by RP-HPLC and eluted as two peaks, I and II corresponding to nonacetylated Tα1 (14.846 min) and Nα-acetylated Tα1 (15.396 min). (b–d) RP-HPLC analysis of samples eluted from SP column with (b) 0.2 M NaCl, (c) 0.3 M NaCl, and (d) 0.5 M NaCl. Nα-acetylated Tα1 was washed out in 0.2 M NaCl fraction (2, peak II), while nonacetylated Tα1 was washed out in 0.5 M NaCl fraction (4, peak I).

Although ProTα and Tα1 have been overexpressed in E. coli previously [19, 22], it was often not determined if the Nα-termianl residue was acetylated. In some cases, this may be due to the difficulty associated with separating Nα-acetylated forms from nonacetylated forms. In this study, we were able to completely separate Nα-acetylated Tα1 and nonacetylated Tα1 by HPLC (Figures 3 and 4). The Nα-acetylated Tα1 was confirmed by MS and MS/MS sequencing.

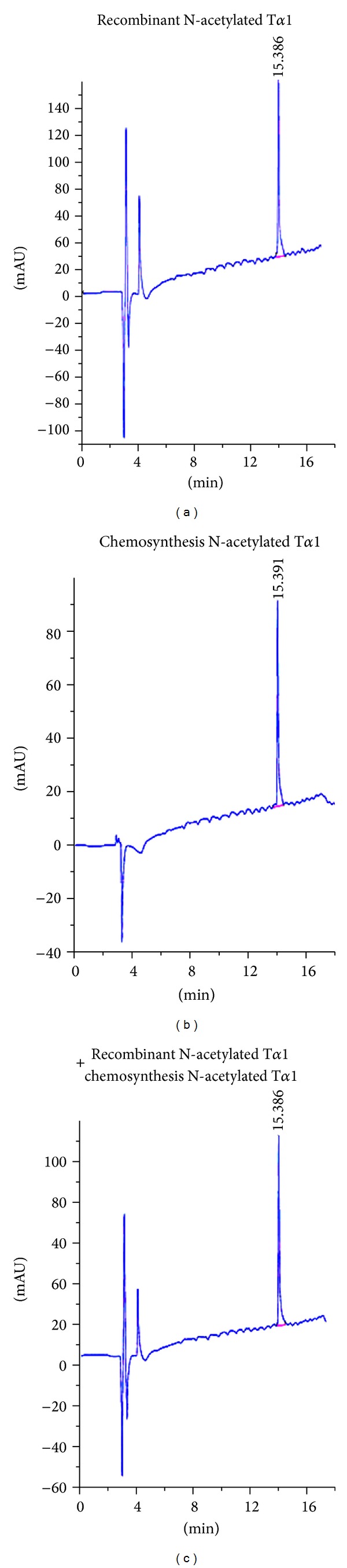

Figure 4.

Identification of recombinant Nα-terminal acetylated Thymosin α1 by RP-HPLC. Recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was analyzed by RP-HPLC on a C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with a programmed acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% TFA, as detailed under “Materials and Methods.” Chromatograms are shown for (a) recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 (15.386 min), (b) chemically synthesized Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 (ZADAXIN, 15.392 min), and (c) mixture of the recombinant Tα1 and chemically synthesized Tα1 (15.392 min).

3.5. Identification of the Nα-Terminal Acetylated Thymosin α1

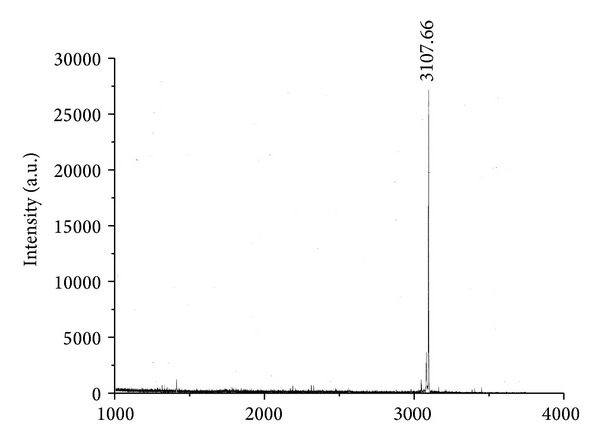

Purified, recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1, and chemically synthesized Nα-acetylated Tα1 were analyzed by RP-HPLC. The elution time of recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was 15.386 min (Figure 4(a)), which was the same as the Nα-acetylated Tα1 produced by chemical synthesis (15.392 min, Figure 4(b)). When the recombinant and chemosynthetic forms of Nα-acetylated Tα1 were mixed and subjected to RP-HPLC, a single peak eluted with a retention time of 15.386 min (Figure 4(c)). The molecular mass of the recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 as determined by Q-TOF mass spectrometry was 3108.79 Da (Figure 5); a mass which is the same as the chemosynthetic peptide and corresponds to the theoretical molecular mass of nonacetylated Tα1 (3065 Da) plus an additional 42 Da increment for the acetyl group.

Figure 5.

The Q-TOF profile of the recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1.

The sequence of the recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was determined by tandem MS. It was found to be “Ac-SDAAVDTSSEITTKDLKEKKEVVEEAEN” (Figure S1a), which is the same as the native and chemosynthetic Nα-acetylated Tα1. Nα-terminal acetylation was confirmed by a m/z of 130.05 for the Nα-terminal amino acid residue (Figure S1b), which corresponds to an acetylated serine residue.

Tα1 had been expressed as a fusion protein or in a concatemer form [22, 31, 32]. Zhou et al. reported that 6 × Tα1 concatemer was successfully expressed in E. coli and cleaved by hydroxylamine to release the Tα1 monomer. However, this version of Tα1 was not acetylated on the Nα-terminal serine residue [22]. In contrast, this study established an efficient method for preparation of the Nα-acetylated Tα1 following expression of ProTα in E. coli. A number of factors make this method easy to scale up for commercial production. Firstly, E. coli can be grown to high-density and is capable of producing large quantities of heterologous protein. ZADAXIN, Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 produced by total chemical synthesis energizes the immune response, helping patients to battle invasive cancers and secondary infections. It has been tested and proven safe, effective, and easy to tolerate in numerous patient populations, including the elderly, previous treatment failures, and patients with depressed immune systems. In this study, we provide an alternative way to produce Nα-terminal acetylated thymosin α1 by cleaving the recombinant protein with legumain, which should be cheaper for large-scale production; as E. coli is the most efficient and economic host for recombinant polypeptide production.

In addition, recombinant human legumain is easily expressed as the proenzyme in yeast P. pastoris after which it can be autocleaved to yield the active enzyme. Only 2 μg of recombinant legumain is needed to process 400 μg of ProTα (data not shown). Finally, the extraction and purification of ProTα were based on thermal denaturation [19] and the use of chromatographic media that are chemically stable (can be regenerated repeatedly), commercially available, and relatively inexpensive.

The isolation of Nα-acetylated Tα1 from recombinant ProTα also confirmed our previous findings that ProTα is Nα-terminally acetylated in E. coli [4]. Acetylation is a common modification in eukaryotic cells, and it plays an important role in protein function and stability. Acetylation, like phosphorylation, can regulate essential cellular processes, such as transcription, nuclear import, microtubule function, and hormonal response [33]. Before this report, a few reports have demonstrated acetylation of proteins expressed in E. coli. However, with the exception of Nα-acetylated Tα1 described here, many of these acetylated proteins are of little clinical utility. Nα-acetylation of proteins is catalyzed by Nα-acetyltransferases (NATs). Three E. coli NATs, namely, RimL, RimJ, and RimI, have already been identified through mutant analysis and are responsible for the acetylation of ribosomal proteins L12, S5, and S18, respectively [34, 35]. Fang et al. recently revealed that Nα-acetylation of recombinant fusion proteins of Tα1 and the ribosomal protein L12 is catalyzed by RimJ in E. coli [31]. Johnson et al. reported a applicable method for the expression and purification of functional N-terminally acetylated eukaryotic proteins by coexpressing the fission yeast NatB complex with the target protein in E. coli [36]. These results can help reveal the function of acetylation in prokaryotes and find additional mechanisms for producing acetylated proteins in E. coli.

4. Conclusion

This study established a method for production of recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 in E. coli, which is a clinical useful peptide, and was produced by chemosynthesis previously. The product consistent with the chemosynthesis of Nα-acetylated Tα1, which was confirmed as Nα-acetylated Tα1 by the elution time in HPLC assay (Figure 3(b)), molecular mass in MS assay (Figure 3(c)), and in MS/MS sequencing (Figure 4). The RP-HPLC showed a single peak in 15.4 min also demonstrated the produced recombinant Tα1 was a uniform component, with nonacetylated Tα1 free.

Supplementary Material

The sequence of recombinant Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 was measured by tandem MS. The sequence of the recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was “Ac-SDAAVDTSSEITTKDLKEKKEVVEEAEN”(a), measured by tandem MS of Q-TOF2, which is same as the native and chemosynthesis Nα-acetylated Tα1. Nα-terminal acetylation was confirmed by m/z of 130.05 for the Nα-terminal amino acid residue, which corresponds to an acetylated serine residue (b).

Authors' Contribution

Bo Liu and Xin Gong contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31200082) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (no. 5102037).

Abbreviation

- ProTα:

Prothymosin α

- Thymosinα1:

Tα1

- HBV/HBC:

hepatitis B and C virus

- NSCLC:

nonsmall cell lung cancer

- Da:

Dalton

- HPLC:

High-performance liquid chromatography

- RP:

Reverse phase

- MS:

Mass spectrometry

- Q-TOF MS:

Quadrupole time-of-fight Mass spectrometry

- AEP:

Lysosomal asparaginyl endopeptidase

- AOX1:

Alcohol oxidase 1

- NATs:

Nα-acetyltransferases

- TFA:

Trifluoroacetic acid.

References

- 1.Polevoda B, Sherman F. The diversity of acetylated proteins. Genome Biology. 2002;3(5, article 6) doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polevoda B, Sherman F. N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;325(4):595–622. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charbaut E, Redeker V, Rossier J, Sobel A. N-terminal acetylation of ectopic recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli . FEBS Letters. 2002;529(2-3):341–345. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J, Chang S, Gong X, Liu D, Ma Q. Identification of N-terminal acetylation of recombinant human prothymosin α in Escherichia coli . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1760(8):1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urbancikova M, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Requirement of amino-terminal modification for striated muscle α-tropomyosin function. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(39):24310–24315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudman D, Hollins BM, Kutner MH, Moffitt SD, Lynn MJ. Three types of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone: bioactivities and half-lives. The American Journal of Physiology. 1983;245(1):E47–E54. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.245.1.E47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takao T, Kobayashi M, Nishimura O, Shimonishi Y. Chemical characterization of recombinant human leukocyte interferon A using fast atom borbardement mass spectrometry. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(8):3541–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honda S, Asano T, Kajio T, Nishimura O. Escherichia coli-derived human interferon-γ with cys-tyr-cys at the N-terminus is partially N α-acylated. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1989;269(2):612–622. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Violand BN, Schlittler MR, Lawson CQ, et al. Isolation of Escherichia coli synthesized recombinant eukaryotic proteins that contain ε-N-acetyllysine. Protein Science. 1994;3(7):1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pflumm MN, Gruber SC, Tsarbopoulos A, et al. Isolation and characterization of an acetylated impurity in Escherichia coli-derived recombinant human interleukin-10 (IL-10) drug substance. Pharmaceutical Research. 1997;14(6):833–836. doi: 10.1023/a:1012127228239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.d’Alayer J, Expert-Bezançon N, Béguin P. Time- and temperature-dependent acetylation of the chemokine RANTES produced in recombinant Escherichia coli . Protein Expression and Purification. 2007;55(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low TL, Goldstein AL. Thymosins: structure, function and therapeutic applications. Thymus. 1984;6(1-2):27–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarandeses CS, Covelo G, Díaz-Jullien C, Freire M. Prothymosin α is processed to thymosin α1 and thymosin α11 by a lysosomal asparaginyl endopeptidase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(15):13286–13293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YF, Zhao W, Zhong YD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of thymosin α-1 and interferon α in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Antiviral Research. 2008;77(2):136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Contreras F, Nevárez-Sida A, Constantino-Casas P, Abud-Bastida F, Garduño-Espinosa J. Cost-effectiveness of chronic hepatitis C treatment with thymosin α-1. Archives of Medical Research. 2006;37(5):663–673. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iino S, Toyota J, Kumada H, et al. The efficacy and safety of thymosin α-1 in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B; results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2005;12(3):300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liaw YF. Thymalfasin (thymosin-α 1) therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;19(supplement 6):S73–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naruse H, Hashimoto T, Yamakawa Y, Iizuka M, Yamada T, Masaoka A. Immunoreactive thymosin α1 in human thymus and thymoma. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1993;106(6):1065–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evstafieva AG, Chichkova NV, Makarova TN, et al. Overproduction in Escherichia coli, purification and properties of human prothymosin α . European Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;231(3):639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wetzel R, Heyneker HL, Goeddel DV, et al. Production of biologically active Nα-desacetylthymosin α1 in Escherichia coli through expression of a chemically synthesized gene. Biochemistry. 1980;19(26):6096–6104. doi: 10.1021/bi00567a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang YF, Yuan HY, Liu NS, et al. Construction, expression and characterization of human interferon α2b-(G4s)n-thymosin α1 fusion proteins in Pichia pastoris . World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11(17):2597–2602. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i17.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L, Lai ZT, Lu MK, Gong XG, Xie Y. Expression and hydroxylamine cleavage of thymosin α 1 concatemer. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2008;2008:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2008/736060.736060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren Y, Yao X, Dai H, et al. Production of Nα-acetylated thymosin α1 in Escherichia coli . Microbial Cell Factories. 2011;10(1, article 26) doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esipov RS, Stepanenko VN, Beyrakhova KA, Muravjeva TI, Miroshnikov AI. Production of thymosin α 1 via non-enzymatic acetylation of the recombinant precursor. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 2010;56(1):17–25. doi: 10.1042/BA20100027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi S, Brickenden A, Choy WY. A new protocol for high-yield purification of recombinant human prothymosin α expressed in Escherichia coli for NMR studies. Protein Expression and Purification. 2008;57(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li DN, Matthews SP, Antoniou AN, Mazzeo D, Watts C. Multistep autoactivation of asparaginyl endopeptidase in vitro and in vivo . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(40):38980–38990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen JM, Dando PM, Rawlings ND, et al. Cloning, isolation, and characterization of mammalian legumain, an asparaginyl endopeptidase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(12):8090–8098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz G, Brandenburg J, Reich M, Burster T, Driessen C, Kalbacher H. Characterization of legumain. Biological Chemistry. 2002;383(11):1813–1816. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macauley-Patrick S, Fazenda ML, McNeil B, Harvey LM. Heterologous protein production using the Pichia pastoris expression system. Yeast. 2005;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1002/yea.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cereghino JL, Cregg JM. Heterologous protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris . FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2000;24(1):45–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang H, Zhang X, Shen L, et al. RimJ is responsible for Nα-acetylation of thymosin α1 in Escherichia coli . Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2009;84(1):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1994-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen PF, Zhang HY, Fu GF, Xu GX, Hou YY. Overexpression of soluble human thymosin α 1 in Escherichia coli . Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2005;37(2):147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kouzarides T. Acetylation: a regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? The EMBO Journal. 2000;19(6):1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa A, Isono S, Sheback A, Isono K. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the genes rimI and rimJ which encode enzymes acetylating ribosomal proteins S18 and S5 of Escherichia coli K12. Molecular & General Genetics. 1987;209(3):481–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00331153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka S, Matsushita Y, Yoshikawa A, Isono K. Cloning and molecular characterization of the gene rimL which encodes an enzyme acetylating ribosomal protein L12 of Escherichia coli K12. Molecular and General Genetics. 1989;217(2-3):289–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02464895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson M, Coulton AT, Geeves MA, Mulvihill DP. Targeted amino-terminal acetylation of recombinant proteins in E. coli . PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015801.e15801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The sequence of recombinant Nα-terminal acetylated Tα1 was measured by tandem MS. The sequence of the recombinant Nα-acetylated Tα1 was “Ac-SDAAVDTSSEITTKDLKEKKEVVEEAEN”(a), measured by tandem MS of Q-TOF2, which is same as the native and chemosynthesis Nα-acetylated Tα1. Nα-terminal acetylation was confirmed by m/z of 130.05 for the Nα-terminal amino acid residue, which corresponds to an acetylated serine residue (b).