Abstract

Although several studies have investigated the association of miRNAs with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the data published so far are not concordant. A reason for these discrepancies may be the fact that most studies used as a control the non-tumorous tissue surrounding the HCC lesion, which is almost invariably affected by cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis, as well as other pathological conditions such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Moreover, HCC is often analyzed as a single group regardless of the different viral etiologies. In this study, we investigated miRNAs differentially expressed in HCV-related HCC by comparing the tumorous tissues to a wide range of liver specimens, including healthy livers obtained from liver donors and patients who underwent liver resection for angioma, in addition to tissues from various acute and chronic liver diseases, including HCV-related cirrhosis not associated with HCC, HCV-related cirrhosis associated with HCC, and HBV-associated acute liver failure (ALF). Our study examined the whole set of 2,226 human miRNAs, including 1,121 pre miRNAs and 1,105 mature miRNAs, available in a microarray platform.Stringent statistical methods were applied to reduce the risk of false discoveries to less than 1%. Our data identified 18 miRNAs exclusively expressed in HCV-associated HCC, characterized by high specificity and selectivity versus all other liver diseases and healthy conditions, and connected into a regulatory network pivoting on p53, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and all-trans retinoic acid signaling.

Keywords: Liver, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis C virus, microRNA, pathogenesis

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, about 22 nucleotide long non-coding RNA molecules that bind to 6–7-nucleotide complementary sequences of mRNAs, usually resulting in post-transcriptional down-regulation of gene expression. First discovered in C. elegans in 1993,1 miRNAs were recognized as an essential, evolutionarily conserved class of genetic regulators only in 2003.2 A single miRNA can target hundreds of mRNAs but at the same time a single mRNA can be targeted by several miRNAs, thus forming a complex regulatory network that modulates basic functions such as cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis. Specific miRNA perturbations have been correlated with various diseases and in particular with the development of tumors. Over the last decade, the number of studies of miRNA in cancer has increased about 10 times every two years.3

In 2006, Murakami et al.were the first to identify a set of miRNAs differentially expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).4 Subsequently, a large number of studies have been performed to define the specific miRNA profile of HCC.3,5-8 However, no definite consensus has emerged on the miRNAs that are specifically associated with HCC. This may be in part attributed to the presence of different miRNA-related subclasses of HCC 9 but mainly to the fact that only few studies have compared HCC with bona fide normal liver tissue,10-13 while the great majority evaluated the differential expression of miRNA in HCC versus the surrounding nontumor tissue used as control. However, tumor-adjacent tissues are typically affected by chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis of viral or non-viral etiology, including alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). In addition,a limitation of the current studies is that HCC cases are often analyzed as a single group regardless of the hepatitis virus involved. In fact, there is limited information on miRNAs specifically expressed in distinct groups of HCV- or HBV-related HCC.11 All these facts may have considerably reduced the specificity and sensitivity for the identification of miRNA associated with HCC, thus limiting their usefulness as reliable biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets in HCC.

The recent detection of miRNAs in serum 14 has opened new perspectives for the development of non-invasive tests that circumvent the difficulty in obtaining tissue samples from patients with severe/acute liver diseases. It has been shown that certain serum miRNAs are significantly associated with HCC, chronic hepatitis and other liver diseases, including drug-induced hepatic injuries.15-17 However, serum miRNA does not seem to be correlated with the miRNA found in liver tissue. For example, miR-122, a liver-specific miRNA that is invariably decreased in all liver diseases investigated to date (NASH, NAFLD, HCC, liver fibrosis, hepatitis B and drug-induced liver injury),8,18 exhibits increased levels in the serum of HCC and chronic hepatitis patients.17 Thus, while serum miRNAs may represent a valuable alternative to tissue miRNAs for the identification of disease biomarkers, they are unlikely to provide mechanistic insights into the development and progression of HCC.

To obtain a reliable profile of miRNAs specifically associated with HCC, we investigated the miRNAs expressed in six types of liver tissues: HCV-associated HCC (HCC), HCC-associated non-tumorous cirrhosis (HCC-CIR), HCV- associated cirrhosis without HCC (CIR), HBV-associated acute liver failure (ALF), normal liver tissue surrounding angioma (NL) and normal liver from liver donors (LD). Characteristic features of our study were: (a) the wide range of healthy and diseased liver tissues examined for which a histological diagnosis was available; (b) the number of miRNAs investigated (1,105 pre-miRNAs and 1,105 mature miRNA); (c) the stringent statistical methods employed to reduce the risk of false discoveries to less than 1%; and (d) the homogeneous methods of tissue sampling (surgical liver specimens), RNA extraction, amplification and detection.

Of the 2,226 miRNA investigated, we identified only 18 miRNA specifically associated with HCC compared to the other five groups of liver tissues. These miRNAs are connected in a molecular network that includes p53, PTEN and all-trans retinoic acid, suggesting a direct involvement of these cell-growth regulators in the pathogenesis of HCC.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Liver specimens were obtained from 34 patients at the time of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), from two patients undergoing liver resection for HCV-associated HCC, and from 7 patients undergoing liver resection for liver angioma. The demographic features of the patients are shown in Table 1. We studied 26 liver specimens obtained from 10 patients with HCV-associated HCC, including 9 specimens from the tumor area (HCC) and 17 specimens from the surrounding non-tumorous tissue affected by cirrhosis (HCC-CIR) because in one of the 10 patients, miRNA expression profiling was performed only in the periphery but not in the tumor; 18 specimens from 10 patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis without HCC (CIR); and 13 specimens from 4 patients with HBV-associated acute liver failure (ALF).Among the patients with HCV-associated HCC, according to Edmondson and Steiner grading,19 5 patients had G2 and 5 had G3. As a control group, we studied individual liver specimens from 12 liver donors (LD) and from 7 subjects who underwent hepatic resection for liver angioma (NL). Within the control group, none of the subjects had evidence of active infection with hepatitis viruses, as previously reported.20 The results of liver enzymes were normal in all but one liver donor who showed very slightly elevated ALT (49 U/L, normal value <42 U/L).The liver histology was available at the time of this study in all patients.The majority (11/17, 65%) had completely normal liver histology, whereas the remaining 6 had minimal alterations, including mild steatosis in 5 (29%) and mild portal inflammation in one (6%). Up to 5 liver specimens were obtained for each patient. Each liver specimen was divided in two pieces: one was snap frozen and the other was fixed in formalin. Snap-frozen samples were stored at −80 °C and were used for miRNA expression profiling by microarray; fixed liver tissues were used for liver histology. All liver specimens were analyzed histologically. Liver and serum specimens and clinical data were received under code to protect the identity of the study subjects.Written informed consent was obtained from each patient or from the next of kin. The study was approved by the Review Board of the Hospital Brotzu, Cagliari, Italy, and by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research, granted on the condition that all samples be made anonymous.

Table 1.

Demographic features of the different groups of subjects studied.

| HCV-associated HCC (HCC)* | HCC-associated cirrhosis (HCC-CIR) | HCV- associated cirrhosis (CIR) | HBV-associated acute liver failure (ALF) | Normal liver (NL)** | Liver donors (LD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 9 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 12 |

| No. of liver specimens analyzed | 9 | 17 | 18 | 13 | 7 | 12 |

| Male gender (%) | 89 | 90 | 100 | 50 | 14 | 58 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 55 ± 10 | 55 ± 10 | 48 ± 7 | 42 ± 7 | 46 ± 13 | 36 ± 21 |

HCC denotes hepatocellular carcinoma.

Obtained during liver resection for angioma.

miRNA analysis and nomenclature

We performed microRNA expression profiling of all liver specimens using Affymetrix GeneChip miRNA2.0 arrays, which contain 1,121 pre-miRNA (mir-), and 1,105 mature miRNA (miR-) probe sets.Total RNA, including microRNA, was extracted from frozen liver specimens using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality and integrity was assessed with the RNA 6000 Nano Assay on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. 500ng of total RNA, including microRNA, was poly(A) tailed and then directly ligated to a fluorescent dendrimer (a branched single and double stranded DNA molecule conjugated to biotin) using the FlashTag Biotin HSR RNA Labeling Kit (Affymetrix).An ELOSA was performed prior to hybridization and analysis of the arrays in order to verify that all miRNAs were correctly labeled with the biotin molecule at the 3′ end.Standard Affymetrix protocols were used for hybridization, staining, washing, and scanning of the arrays (available at www.affymetrix.com). All samples passed the quality control (QC) assessment performed with the miRNA QCTool available through Affymetrix, using chip-specific quality control probes. According to the changes incorporated in the miRBase 17 (miRBase.org), the “*” symbol (or the equivalent “-star” suffix of Affymetrix IDs) is replaced by the “−3p” nomenclature. In addition, the “−5p” nomenclature is considered equivalent to the short miRNA name (i.e., miR-199a-5p and miR-199a).

Statistical analysis

Raw microarray data (cel files) were imported into BRB-ArrayTools v 4.2.1 (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-Array-Tools.html).21 Probe set summaries were computed using RMA (Robust Multi-Array) algorithm. To adjust for differences in labeling intensities and hybridization, a global normalization was made by aligning signal intensities of data arrays across the medians. Data obtained from multiple specimens of the same patient were averaged; in HCC patients, tumor and non-tumor specimens were maintained as distinct groups. A multivariate permutation F-test 22 with a maximum proportion of false discovery of 1% with 80% confidence level was used to identify miRNA with different concentration levels among the six types of liver tissues examined. Pair-wise t-test comparisons were then performed using this subset of miRNAs in order to identify the miRNAs that differed consistently (that is, having the same direction of change, in all pairwise comparisons) and significantly (p <= 0.01, in all pairwise comparisons) in a specific group of livers compared to the other five groups. Hereafter, these miRNAs will be conventionally referred to as ‘exclusive’ miRNAs. For each exclusive miRNA, we also calculated (a) the fold change (FC), (b) the AUC (area under the Receiver Operator Characteristic curve), (c) the sensitivity and (d) specificity based on the best cutoff value identified by the ROC curve. All these parameters were evaluated comparing the reference group expressing the exclusive miRNA to the other five groups pooled together. The relationship between the exclusive miRNAs and liver diseases were also visualized by the heat-map and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Data processing was performed using Statistica (StatSoft Inc., www.statsoft.com), Multibase (v. 2012, Numerical Dynamics.com) and IPA (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, release June 2012). MicroRNA microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession number GSE 40744).

Results

A total of 182 miRNAs (8% of the whole set of 2,226 human miRNA probe sets present in the microarray chip) were found to be differentially expressed among the six types of liver tissues examined (i.e., HCC, HCC-CIR, CIR, ALF, NL and LD) using a multivariate permutation F-test with a false discovery rate <= 1% (Supplementary Table 1). Thus, only 2 of the 182 miRNAs would be expected to be false positives. Pairwise t-test comparisons between single groups of livers were then performed on the 182 differentially expressed miRNAs using a significance threshold of p=0.01. A subset of 55 exclusive miRNAs was identified, which were significantly and consistently expressed in the same direction of change in only a single group compared to all the other groups. Among these 55 unique miRNAs, 18 miRNA were exclusively expressed in HCC, 30 in ALF, 4 in LD, 2 in NL and 1 in CIR.

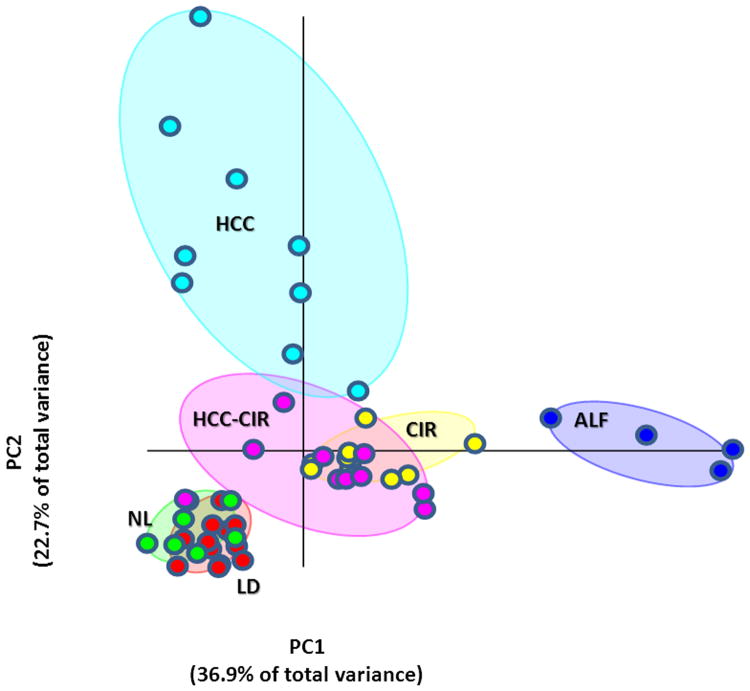

Using these exclusive miRNA, we investigated the relations among the six groups of liver specimens by PCA (Figure 1). Strikingly, this analysis showed HCC and ALF orthogonally aligned at the ends of the PCA axes, a pattern indicative of strongly different and unrelated expression profiles. In addition, the relatively larger nearest-neighbor distance within HCC and ALF PCA clusters denoted a higher heterogeneity of miRNA expression within these groups than within the other groups. HCC was also well separated from HCC-CIR and CIR. By contrast, CIR and HCC-CIR clustered together, suggesting that these two cirrhotic tissues share a common miRNA profile. Consistent with the healthy condition of both LD and normal liver from patients who underwent partial hepatic resection for angioma (NL), the PCA showed a close association between these two groups.

Figure 1.

Principal Component Analysis showing the relations among the six liver disease conditions resulting from 55 differentially expressed miRNAs. The map shows complete separation of HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and HBV-associated acute liver failure (ALF). A partial overlapping was seen between HCV-associated cirrhosis surrounding HCC (HCC-CIR) and HCV-associated cirrhosis without HCC (CIR), as well as between normal livers obtained from patients who underwent liver resection for angioma (NL) and liver donors (LD). The two principal components account for nearly 60% of the total variance expressed by the 55 miRNAs.

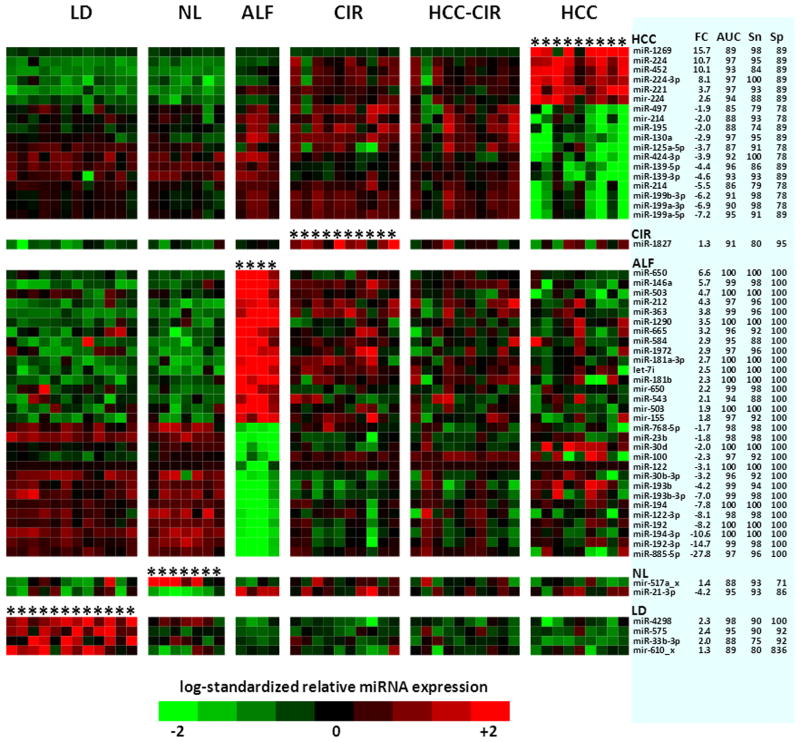

The heat-map (Figure 2) confirmed that the predominant deviations occurred in miRNAs exclusive for HCC (right most panel) and ALF (3rd panel). Healthy livers (LD and NL) showed a miRNA expression pattern opposite to that of HCC and ALF: exclusive miRNAs that were up-regulated in HCC or ALF were down-regulated in healthy livers and vice versa. The same relationship did not apply to cirrhotic livers (CIR and HCC-CIR), which exhibited a random color mosaic, irrespective of the up- or down-regulation of HCC- and ALF-exclusive miRNAs. Figure 2 also shows the fold change (FC), the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity of the 55 exclusive miRNAs. In particular, HCC- and ALF-exclusive miRNAs reached high levels of sensitivity (91 ± 8 and 97 ± 4, respectively, mean ± standard deviation) and specificity (85 ± 6 and 100 ± 0, respectively), which are comparable to those of biomarkers of diagnostic grade. A plot of fold changes of the 55 exclusive miRNAs is also shown in the Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Heat-map of the 55 miRNAs (rows) differentially expressed in the six groups of livers analyzed. Each column represents a single patient (up to 5 liver specimens for each patient), and each row a single miRNA. miRNAs that are up-regulated are shown in shades of red; those down-regulated are in shades of green. The intensity of the color in each cell reflects the level of the corresponding miRNA in the corresponding patient expressed as normalized log2 ratios. Within each group, miRNAs are ordered according to decreasing fold changes (FC). The columns on the right show the FC, area under the ROC curve (AUC), sensitivity (Sn) and specificity (Sp) of each miRNA, relative to the contrast between the group where it was differentially expressed and the remaining five groups. ROC curves of HCC miRNAs are also plotted in Figure 3. HCC, HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma; HCC-CIR, HCV-associated cirrhosis surrounding HCC; CIR, HCV-associated cirrhosis without HCC; ALF, HBV-associated acute liver failure; NL, normal liver from liver resection for angioma; LD, normal livers from liver donors. No data are shown for HCC-CIR since no differentially expressed miRNAs were found in this group of livers.

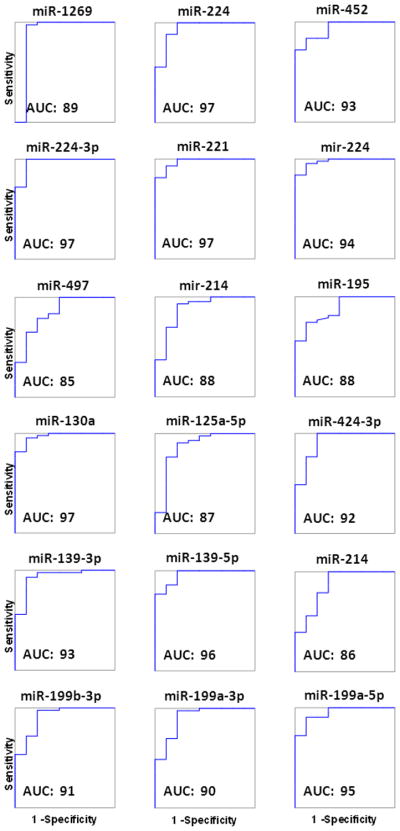

The ROC curves of the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs are plotted in Figure 3. Four of these miRNAs(miR-224, miR-224-3p, miR-221 and miR-130a) showed AUC values of 97. Interestingly, among the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs there were three pairs of mature miRNAs: miR-224 and miR-224-3p (both up-regulated); miR-139-5p and miR-139-3p (down-regulated); and miR-199a-5 and miR-199a-3p, (down-regulated). The detection of the miRNA-224 pair is supported by the presence of the precursor (mir-224) among the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs.

Figure 3.

ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve analysis of the 18 miRNA differentially expressed in HCC. The average AUC (area under the curve) of all 18 miRNAs is 91.9 ± 4.1 (mean ± SD). Sensitivity and specificity values are shown in Figure 2.

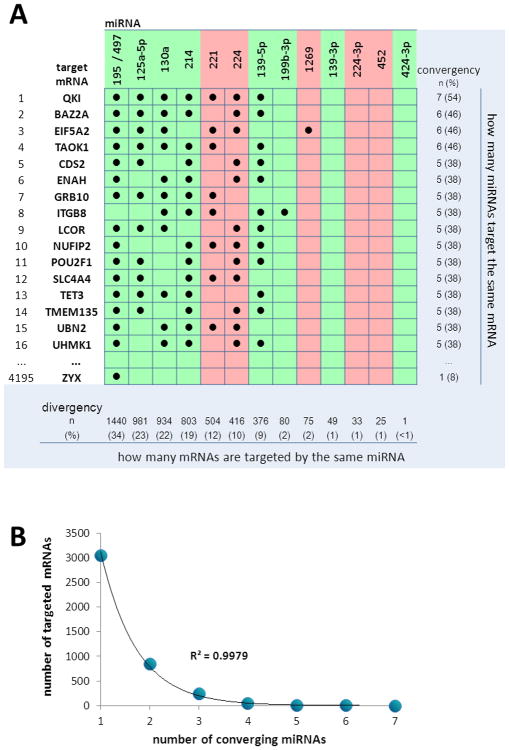

A set of 4195 mRNAs potentially targeted by the HCC-exclusive mature miRNAs was obtained from TarBase, TargetScan, miRecords and Ingenuity Expert/Assistant Findings databases, using data validated by experimental observations or high confidence predictions. The screening was done for 14 of the 16 mature miRNAs, as data of miR-199a-3p and miR-199a-5p were not available. The analysis made it possible to identify the different miRNAs targeting the same mRNA (miRNA convergency) as well as the different mRNAs targeted by the same miRNA (miRNA divergency) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Relationship between 14 HCC-exclusive mature miRNAs and their putative target mRNAs obtained from TarBase, TargetScan, miRecords and Ingenuity Expert/Assistant Findings, using data validated by experimental observations or high confidence predictions. A. Two-way table showing miRNAs which share the same target mRNA (miRNA convergency)in the rows, and mRNAs targeted by the same miRNA (miRNA divergency) in the columns. The table shows only the first 16 mRNAs with the highest miRNA convergency. Mir-195 and miR-497 are in the same column as they have the same seed sequence. The maximum convergency is shown by 7 miRNAs (54%) which target QKI. The maximum divergency is shown by miR-195/miR-497, which target 1440 mRNAs (34% of the 4195mRNAs identified). Data of miR-199a-3p and miR-199a-5p were not available. The red color indicates miRNAs that are up-regulated in HCC; green indicates miRNAs down-regulated. B. Relation between the number of targeting miRNAs and the number of targeted mRNAs. Most of mRNAs are targeted by one or two miRNAs. The line shows the exponential fitting.

The highest convergency is shown by eight miRNAs (miR-195, miR-497, miR-214, miR-224, miR-139-5p, miR-125a-5p, miR-130a and miR-221), all potentially able to bind to QKI (quaking homolog) mRNA. QKI is a member of the signal transduction and activation of RNA (STAR) family of RNA-binding proteins, which has recently been identified as a tumor suppressor in various cancers (glioblastoma multiforme, gastric and colon cancer), 23-25 but its role in HCC remains to be established.

The highest divergency is shown by miR-195 and miR-497, two miRNAs with the same seed sequence, potentially able to bind to 1440 mRNAs, equivalent to 34% of all mRNAs targeted by the set of HCC-exclusive miRNAs. Figure 4A also shows that the clusters of miRNAs targeting the same mRNA include both down-regulated and up-regulated miRNAs, a fact which denotes the extreme complexity of the post-transcriptional regulation played by miRNAs. However, the correlation between the number of converging miRNAs and the number of targeted mRNAs shows that most of mRNAs are targeted by a single miRNA (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the data fit perfectly to an exponential function, suggesting that the relationship between targeting miRNA and targeted mRNA follows a precise, although not yet parametrically defined, statistical distribution.

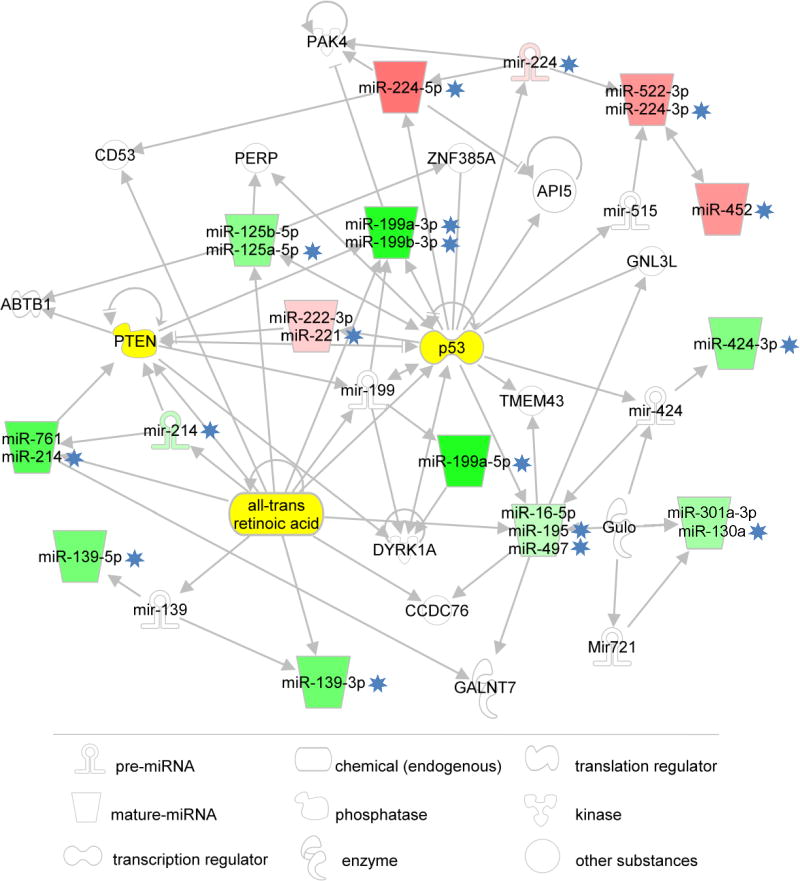

IPA core analysis attributed the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs to the HCC category (p = 5.42×10−11) yielding a single network that included 16 of the 18 miRNAs, with the only exclusion of miR-452 and miR-1269. However, miRNA-452 was added manually to the network as this miRNA was recently shown to be coordinately regulated with its neighboring miRNA-224 in HCC through epigenetic mechanisms. 26 The IPA network with this update is shown in Figure 5. Interestingly, the network pivots on p53, PTEN and RA (all-trans retinoic acid), three important modulators of cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis and cell cycle, which also play an important role in the development of HCC.27-28 Our data depict ALF as an extreme condition, totally different from all the other liver conditions investigated. All 30 ALF-exclusive miRNAS showed very high sensitivity and specificity values. The role of these miRNAs in ALF is currently being investigated in a separate study.According to the definition of exclusive miRNAs used in this study, the presence of groups with similar characteristics would reduce the probability of detecting exclusive miRNAs in these groups. This may explain why only a single exclusive miRNA was detected in CIR and none in HCC-CIR livers. However, four (miR-4298, miR-575, miR-33b-3p and mir-610_x) and two (mir-517a_x, miR-21-3p) miRNAs were found to be exclusively expressed by liver donors and normal livers, respectively.

Figure 5.

Network showing the relationship among 17 HCC-exclusive miRNAs detected in this study (asterisks), obtained using IPA. Sixteen miRNAs were automatically mapped by IPA. MiR-452 was added manually on the basis of data found in the literature. Only miRNA-1269, so far reported only in a case of breast tumor, is not represented in the network. When more than one miRNAs are associated with the same icon, the first one is that nominally shown in the pathway; the others (with the exception of miR-452) are indicated by IPA as synonyms. Mature miRNAs are represented by trapezoids. Pre-miRNAs are Ω-shaped (hairpin-like). The green and red colors represent negative and positive fold changes, respectively. The intensity of the color is indicative of the magnitude of the FC. Note that miRNAs with asterisks associated with the same icon have approximately the same FC, as shown in Figure 2. Most of the miRNAs pivot on p53, PTEN and all-trans retinoic acid (visualized in yellow).

Discussion

The expression of miRNAs associated with HCC was first investigated in 2006 by Murakami and colleagues who identified 8 miRNAs differentially expressed in HCC by comparing samples of HCC with paired samples of adjacent non-tumorous tissue.4 Some of these miRNAs were confirmed in subsequent studies.11-13,29-30 However, in recent years, the number of miRNAs associated with HCC has exponentially grown, and a recent review produced a list of 112 miRNAs associated to HCC identified in 17 studies.5 The most consistently detected was miR-199a, reported by 7 out of 17 studies. On the other hand, a total of 74 miRNAs (66% of the entire set) were reported only in individual studies, demonstrating a substantial lack of consensus among the different reports. These discrepancies have been attributed to differences among miRNA probes, staging and grade of malignancy of the tumor, and etiological factors. The latter in particular are difficult to control due the coexistence of infections by hepatitis viruses, metabolic disorders, and liver fibrosis underlying HCC. The robustness of the association with HCC, irrespective of the etiologic factors, is evident in the case of miRNA 199a/b-3p, the third most highly expressed miRNA in the liver,11 which was found to be consistently decreased in HCC in patients with HBV infection,11 HCV infection (data from the present study) and alcohol consumption.29 The demonstration of a causative relationship between miR-199a/b-3p and HCC was further confirmed by the correlation of this miRNA with poor survival, shorter time to tumor recurrence and inhibition of HCC growth both in vivo and in vitro after miRNA 199a/b-3p administration, along with down-regulation of growth- and tumor-promoting pathways (mTOR, c-MET, PAK4/Raf/MERK/ERK).10-11,31 However, it is possible that certain miRNAs are selectively expressed according to the different HCC etiology. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found only a small fraction (20%) of miRNAs in common between HCV-related HCC and virus-negative, alcohol-related HCC (data of the present study and ref. 29, respectively), suggesting that alcohol-related and HCV-related HCCs are regulated, at least in part, by different miRNA profiles. These observations underscore the need for an accurate etiological diagnosis to link differential miRNA expression to specific liver conditions.

The identification of HCC-exclusive miRNAs is important in the perspective of identifying new diagnostic tools and potential therapeutic targets with high sensitivity (low false-negative error) and specificity (low false-positive error) for this highly lethal form of human cancer. In this respect, our study was aimed at extending the comparison of miRNA expression in HCV-related HCC to a wider range of liver diseases and healthy conditions, not included in earlier studies, in order to provide more reliable sensitivity and specificity data. Among the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs identified in this study, several were already reported in previous studies, including miR-221 and miR-224 (found in 52% of the previous reports), miR-199a-5p, miR-195, miR-214, miR-199a-3p, miR-125a-5p, miR-139-5p, miR-130a, miR-199b-3p, miR-139-3p, miR-224-3p and miR-452. The exceptions are represented by 3 of the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs (miR-497, miRNA-1269 and miR-424-3p), which were not previously reported in HCC studies. They include miR-497, which has been found in various tumors but not in HCC,32-34 miRNA-1269, which has been found only in a case of breast tumor,35 and miR-424-3p, which has never been associated with cancer. Conversely, several miRNAs indicated in previous studies as differentially expressed in HCC were not found to be exclusive for HCV-related HCC in our study. For instance, we found that let-7a and miR-200b, two miRNAs often reported as down-regulated in HCC,36-39 are down-regulated in HCC compared to other diseases (CIR, HCC-CIR and ALF), but not compared to healthy livers (NL and LD), which were not commonly used for comparison in previous studies. Also, miR-21, usually indicated as up-regulated in HCC,36,40-42was even more expressed in ALF.

The presence of all but one of the 18 HCC-exclusive miRNAs in a network that includes p53, PTEN and RA43-44 is consistent with the fact that these growth modulators are directly involved in the pathogenesis of HCC.27-28 p53, PTEN and RA are prominent tumor suppressors whose inactivation has been found to be responsible for the development of the majority of human cancers. This suggests that their molecular pathways play an essential, although not specific, role in the development of HCV-related HCC. These considerations corroborate the importance of identifying HCC-exclusive miRNAs for the development of new diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies for HCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Cancer Institute.Giacomo Diaz was the recipient of a grant from Fondazione Banco di Sardegna (739/2011.1045), Sassari, Italy.

Footnotes

Brief description of the study: HCC miRNAs have been previously investigated using as control the surrounding non-tumorous tissue, which is typically affected by cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis, and often associated with HBV or HCV infection. Access to a unique series of specimens, including normal livers, permitted to identify18 miRNAs exclusively associated with HCV-related HCC that are characterized by high specificity and selectivity versus all other liver diseases and healthy conditions, and intimately connected into a regulatory network.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XW, Heegaard NH, Orum H. MicroRNAs in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1431–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murakami Y, Yasuda T, Saigo K, Urashima T, Toyoda H, Okanoue T, Shimotohno K. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma and non-tumorous tissues. Oncogene. 2006;25:2537–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borel F, Konstantinova P, Jansen PL. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of miRNA signatures in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1371–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haybaeck J, Zeller N, Heikenwalder M. The parallel universe: microRNAs and their role in chronic hepatitis, liver tissue damage and hepatocarcinogenesis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13287. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang S, He X. The role of microRNAs in liver cancer progression. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:235–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr TA, Korenblat KM, Davidson NO. MicroRNAs and liver disease. Transl Res. 2011;157:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toffanin S, Hoshida Y, Lachenmayer A, Villanueva A, Cabellos L, Minguez B, Savic R, Ward SC, Thung S, Chiang DY, Alsinet C, Tovar V, et al. MicroRNA-based classification of hepatocellular carcinoma and oncogenic role of miR-517a. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1618–28 e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fornari F, Milazzo M, Chieco P, Negrini M, Calin GA, Grazi GL, Pollutri D, Croce CM, Bolondi L, Gramantieri L. MiR-199a-3p regulates mTOR and c-Met to influence the doxorubicin sensitivity of human hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5184–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou J, Lin L, Zhou W, Wang Z, Ding G, Dong Q, Qin L, Wu X, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Tian W, Zhang Q, et al. Identification of miRNomes in human liver and hepatocellular carcinoma reveals miR-199a/b-3p as therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:232–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Xie L, He X, Li J, Tu K, Wei L, Wu J, Guo Y, Ma X, Zhang P, Pan Z, Hu X, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of microRNAs in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1616–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su H, Yang JR, Xu T, Huang J, Xu L, Yuan Y, Zhuang SM. MicroRNA-101, down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1135–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrie CH, Gal S, Dunlop HM, Pushkaran B, Liggins AP, Pulford K, Banham AH, Pezzella F, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, Hatton CS, Harris AL. Detection of elevated levels of tumour-associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:672–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomimaru Y, Eguchi H, Nagano H, Wada H, Kobayashi S, Marubashi S, Tanemura M, Tomokuni A, Takemasa I, Umeshita K, Kanto T, Doki Y, et al. Circulating microRNA-21 as a novel biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Zhang S, Marzolf B, Troisch P, Brightman A, Hu Z, Hood LE, Galas DJ. Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813371106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, Wu C, Che X, Wang L, Yu D, Zhang T, Huang L, Li H, Tan W, Wang C, Lin D. Circulating microRNAs, miR-21, miR-122, and miR-223, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or chronic hepatitis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:136–42. doi: 10.1002/mc.20712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szabo G, Sarnow P, Bala S. MicroRNA silencing and the development of novel therapies for liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:462–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edmondson HA, Steiner PE. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7:462–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195405)7:3<462::aid-cncr2820070308>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farci P, Diaz G, Chen Z, Govindarajan S, Tice A, Agulto L, Pittaluga S, Boon D, Yu C, Engle RE, Haas M, Simon R, et al. B cell gene signature with massive intrahepatic production of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in hepatitis B virus-associated acute liver failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8766–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003854107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon R, Lam A, Li MC, Ngan M, Menenzes S, Zhao Y. Analysis of gene expression data using BRB-ArrayTools. Cancer Inform. 2007;3:11–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korn EL, Li MC, McShane LM, Simon R. An investigation of two multivariate permutation methods for controlling the false discovery proportion. Stat Med. 2007;26:4428–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichimura K, Mungall AJ, Fiegler H, Pearson DM, Dunham I, Carter NP, Collins VP. Small regions of overlapping deletions on 6q26 in human astrocytic tumours identified using chromosome 6 tile path array-CGH. Oncogene. 2006;25:1261–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang G, Fu H, Zhang J, Lu X, Yu F, Jin L, Bai L, Huang B, Shen L, Feng Y, Yao L, Lu Z. RNA-binding protein quaking, a critical regulator of colon epithelial differentiation and a suppressor of colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;13:231–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bian Y, Wang L, Lu H, Yang G, Zhang Z, Fu H, Lu X, Wei M, Sun J, Zhao Q, Dong G, Lu Z. Downregulation of tumor suppressor QKI in gastric cancer and its implication in cancer prognosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012(422):187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Toh HC, Chow P, Chung AY, Meyers DJ, Cole PA, Ooi LL, Lee CG. MicroRNA-224 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma through epigenetic mechanisms. FASEB J. 2012;26:3032–41. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen JS, Wang Q, Fu XH, Huang XH, Chen XL, Cao LQ, Chen LZ, Tan HX, Li W, Bi J, Zhang LJ. Involvement of PI3K/PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway in invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Association with MMP-9. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:177–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu HC, Tseng HJ, Lai PL, Lee PH, Peng SY. Expression of p53 gene in 184 unifocal hepatocellular carcinomas: association with tumor growth and invasiveness. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4691–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borel F, Han R, Visser A, Petry H, van Deventer SJ, Jansen PL, Konstantinova P. Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter genes up-regulation in untreated hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by cellular microRNAs. Hepatology. 2012;55:821–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.24682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong QW, Ching AK, Chan AW, Choy KW, To KF, Lai PB, Wong N. MiR-222 overexpression confers cell migratory advantages in hepatocellular carcinoma through enhancing AKT signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:867–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Lee UJ, Kim MN, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Lee MY, Choung S, Kim YJ, Choi YC. MicroRNA miR-199a* regulates the MET proto-oncogene and the downstream extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18158–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo ST, Jiang CC, Wang GP, Li YP, Wang CY, Guo XY, Yang RH, Feng Y, Wang FH, Tseng HY, Thorne RF, Jin L, et al. MicroRNA-497 targets insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor and has a tumour suppressive role in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan LX, Huang XF, Shao Q, Huang MY, Deng L, Wu QL, Zeng YX, Shao JY. MicroRNA miR-21 overexpression in human breast cancer is associated with advanced clinical stage, lymph node metastasis and patient poor prognosis. RNA. 2008;14:2348–60. doi: 10.1261/rna.1034808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D, Zhao Y, Liu C, Chen X, Qi Y, Jiang Y, Zou C, Zhang X, Liu S, Wang X, Zhao D, Sun Q, et al. Analysis of MiR-195 and MiR-497 expression, regulation and role in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1722–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persson H, Kvist A, Rego N, Staaf J, Vallon-Christersson J, Luts L, Loman N, Jonsson G, Naya H, Hoglund M, Borg A, Rovira C. Identification of new microRNAs in paired normal and tumor breast tissue suggests a dual role for the ERBB2/Her2 gene. Cancer Res. 2011;71:78–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connolly E, Melegari M, Landgraf P, Tchaikovskaya T, Tennant BC, Slagle BL, Rogler LE, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, Rogler CE. Elevated expression of the miR-17-92 polycistron and miR-21 in hepadnavirus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the malignant phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:856–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gramantieri L, Ferracin M, Fornari F, Veronese A, Sabbioni S, Liu CG, Calin GA, Giovannini C, Ferrazzi E, Grazi GL, Croce CM, Bolondi L, et al. Cyclin G1 is a target of miR-122a, a microRNA frequently down-regulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6092–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang XH, Wang Q, Chen JS, Fu XH, Chen XL, Chen LZ, Li W, Bi J, Zhang LJ, Fu Q, Zeng WT, Cao LQ, et al. Bead-based microarray analysis of microRNA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: miR-338 is downregulated. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:786–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang J, Gusev Y, Aderca I, Mettler TA, Nagorney DM, Brackett DJ, Roberts LR, Schmittgen TD. Association of MicroRNA expression in hepatocellular carcinomas with hepatitis infection, cirrhosis, and patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:419–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:647–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pineau P, Volinia S, McJunkin K, Marchio A, Battiston C, Terris B, Mazzaferro V, Lowe SW, Croce CM, Dejean A. miR-221 overexpression contributes to liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:264–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907904107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ladeiro Y, Couchy G, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P, Pelletier L, Rebouissou S, Zucman-Rossi J. MicroRNA profiling in hepatocellular tumors is associated with clinical features and oncogene/tumor suppressor gene mutations. Hepatology. 2008;47:1955–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.22256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daikoku T, Hirota Y, Tranguch S, Joshi AR, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Ellenson LH, Dey SK. Conditional loss of uterine Pten unfailingly and rapidly induces endometrial cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5619–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le MT, Xie H, Zhou B, Chia PH, Rizk P, Um M, Udolph G, Yang H, Lim B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA-125b promotes neuronal differentiation in human cells by repressing multiple targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5290–305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01694-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.