Abstract

Current research has evaluated the intrinsic tumor-tropic properties of stem cell carriers for targeted anticancer therapy. Our laboratory has been extensively studying in the preclinical setting, the role of neural stem cells (NSCs) as delivery vehicles of CRAd-S-pk7, a gliomatropic oncolytic adenovirus (OV). However, the mediated toxicity of therapeutic payloads, such as oncolytic adenoviruses, toward cell carriers has significantly limited this targeted delivery approach. Following this rationale, in this study, we assessed the role of a novel antioxidant thiol, N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA), to prevent OV-mediated toxicity toward NSC carriers in an orthotropic glioma xenograft mouse model. Our results show that the combination of NACA and CRAd-S-pk7 not only increases the viability of these cell carriers by preventing reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced apoptosis of NSCs, but also improves the production of viral progeny in HB1.F3.CD NSCs. In an intracranial xenograft mouse model, the combination treatment of NACA and NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 showed enhanced CRAd-S-pk7 production and distribution in malignant tissues, which improves the therapeutic efficacy of NSC-based targeted antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy. These data demonstrate that the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 may be a desirable strategy to improve the therapeutic efficacy of antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy.

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary brain tumor in adults. Although several treatment options such as surgery, irradiation, and chemotherapy have been attempted, the prognosis for GBM patients is still dismal due to the lack of therapeutic effectiveness.1,2 Even with aggressive and continued treatment, median survival of patients with GBM is only 12–15 months.2,3 The reason for such a poor prognosis is related to GBM's propensity for infiltration, invasion, and integration into normal brain tissues together with its inherent resistance to multimodal treatments.4,5,6 Another important consideration for poor outcome in patients with GBM is the presence of an ultraselective blood–brain barrier, which hinders drug delivery to brain tumors. This is considered to be one of the main problems of systemic chemotherapy against GBM. Therefore, novel and feasible therapeutic strategies that are able to specifically target gliomas and overcome the above-described limitations need to be developed in order to prevent GBM recurrence and enhance the prognosis of affected patients.

Oncolytic adenoviral (OV) therapy with replication-competent viruses is an attractive tool for the treatment of malignant cancers.7 In order to reach a feasible clinical application, OVs need to be safe and nontoxic to normal cells while capable of selectively destroying cancer cells. Our laboratory has extensively studied the CRAd-S-pk7 oncolytic virus, a conditionally replicative adenovirus (CRAd) vector that employs the survivin (S) promoter and a fiber modification containing polylysine (pk7) to selectively transduce and replicate in neoplastic cells.8 We have previously shown that CRAd-S-pk7 enhances cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and oncolytic effect in glioma cells.9 We have also demonstrated that CRAd-S-pk7 oncolytic virotherapy either alone or in combination with temozolomide, a well-known chemotherapeutic agent, increases the survival of mice bearing intracranial glioma xenografts.10 Although successful preclinical results have been obtained with oncolytic adenoviruses in antiglioma therapy, this therapeutic strategy is still limited due to the rapid OV clearance by the host immune system and inefficient viral delivery to the tumor sites.

To overcome this limitation, we have used an FDA-approved immortalized neural stem cell (NSC) line for human clinical trials, HB1.F3.CD, as a delivery vehicle of OVs. This carrier is able to home to tumor areas and evade the host immune response elicited by virus infection. We have shown that CRAd-S-pk7-loaded HB1.F3.CD NSCs were able to suppress anti-adenoviral immune response and enhance antiglioma therapeutic efficacy compared with CRAd-S-pk7 alone.11 Additional in vivo studies have demonstrated that CRAd-S-pk7-loaded HB1.F3.CD cells supported virus replication and maintained their tumor tropic properties for more than a week.11,12 In order to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic vectors, various preclinical studies have investigated the use of combined anticancer drugs with OVs in glioma-bearing animal models. Recently, it was reported that the combination of oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (oHSV-1) and copper inhibitor (ATN-224) significantly decreased glioma growth and prolonged animal survival.13 An additional report has shown that oHSV combined with low-dose-Etoposide was able to increase the survival of cancer stem cell-enriched glioma-bearing mice.14 Taken together, the above results suggest that the combination of oncolytic viruses and chemotherapeutic drugs can provide a potential strategy for antiglioma therapy.

It has been previously shown that oxidative stress (OS) plays a critical role in many biological pathways such as programmed cell death, age-related diseases, tumorigenesis as well as autophagy.15,16 In response to viral infection, reactive oxygen species (ROS) induce the generation of danger signals to activate the innate immune response. Such a ROS-mediated OS can be detrimental to the survival of cell carriers as well as to their ability to carry the therapeutic cargo to distant-targeted sites. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a widely used low-molecular weight thiol antioxidant. The neutralization of the carboxylic group of NAC generated a more lipophilic and cell-permeable component, N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA).17 Recent reports demonstrated that NACA prevents renal epithelial cells from Iohexol-induced apoptosis by blocking p38/iNOS activation.18 In cancer cells, previous reports demonstrated that NAC inhibits rat C6 glioma cell proliferation by reducing intracellular ROS levels in vitro.19 Moreover, inhibition of apoptosis using NAC increases the production of viral progeny in human gastric cancer cells.20 Taken together, these results suggest that NACA is able to protect ROS-induced apoptosis of normal cells, and enhance the replication of therapeutic viruses in tumor cells. Based on these data, we set out to investigate if the antioxidative effects of NACA could prevent the apoptosis of NSCs through reduction of intracellular ROS, and improve the homing capabilities of this stem cell carrier toward the targeted tumor. Increased viability could enhance viral production in the NSC carrier and increase the amount of oncolytic viruses that are delivered to the neoplastic area, therefore, augmenting the therapeutic efficacy of this combined therapy.

Here, we have carried out experiments to determine the therapeutic effects of the combination of NACA and CRAd-S-pk7 OV-loaded NSCs on glioma progression. Our in vitro results indicate that NACA treatment combined with CRAd-S-pk7-loaded HB1.F3.CD NSCs increases the production of viral progeny and significantly enhances glioma cell oncolysis compared with CRAd-S-pk7-loaded NSCs alone. We also found that NACA decreases viral-induced levels of intracellular ROS and prevents CRAd-S-pk7-induced apoptosis of NSCs. Furthermore, we observed that the combined treatment increases virus production in the stem cell carrier and enhances apoptosis of glioma tissues, which leads to a higher animal survival. Therefore, we propose that NACA could be a potential partner for a combination with CRAd-S-pk7-loaded NSCs in antiglioma therapy. Such a combined approach could potentially augment the antiglioma therapeutic efficacy of CRAd-loaded NSCs by improving the production of viral progeny in cell carriers, increasing the amount of oncolytic viruses that is delivered to the tumor site and enhancing tumoral apoptosis.

Results

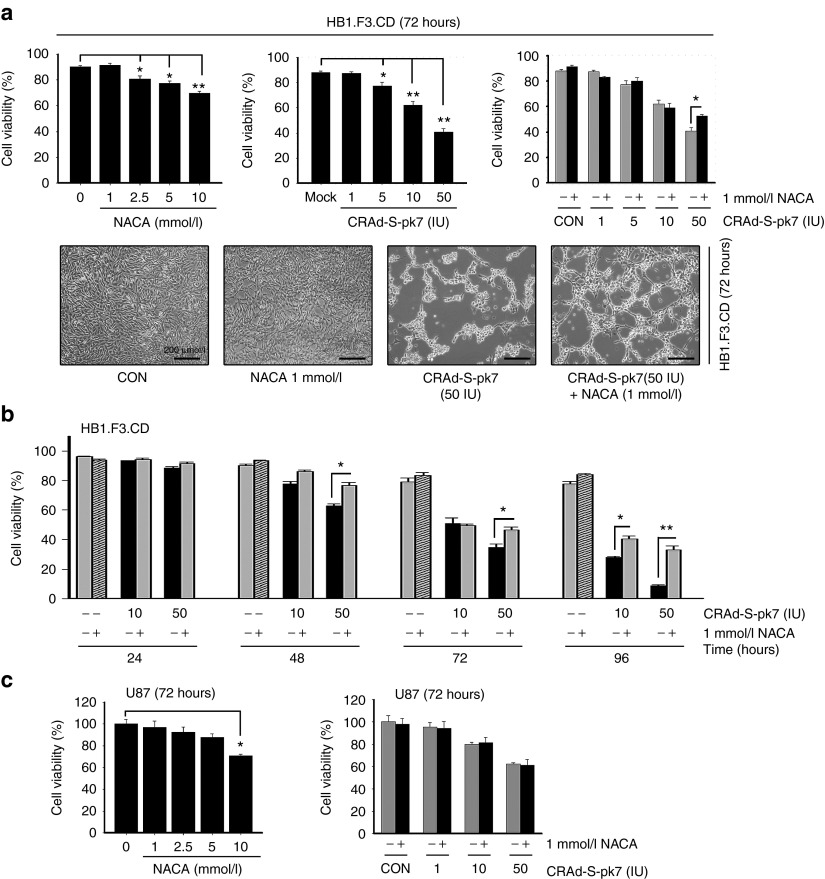

NACA improves the viability of NSC carriers loaded with CRAd-S-pk7

A previous report showed that the oncolytic virus infection followed by NAC treatment was able to increase the production of OVs in tumor cells.20 In addition, we showed that HB1.F3.CD NSC carriers are permissive for CRAd-S-pk7 infection and replication.11 Hence, we hypothesized that the antioxidant effects of NACA could inhibit cellular apoptosis and therefore increase the intracellular production of CRAd-S-pk7 loaded in HB1.F3.CD stem cell carriers. To test the antiapoptotic effects of NACA on OV-loaded NSCs, we first assessed the effect of NACA combined with CRAd-S-pk7 on the viability of both NSCs and glioma cells. To measure NACA-related cytotoxicity, we used MTT assay and trypan blue exclusion test at 72 hours after treatment. The results revealed that NACA was toxic to NSCs at concentrations over 1 mmol/l (Figure 1a), whereas toxicity was observed in U87 cells at a concentration of 10 mmol/l (Figure 1c). The 1 mmol/l concentration was optimal because it allowed us to evaluate the production of infectious adenoviral progeny without affecting the viability of NSCs. Therefore, we chose the concentration of 1 mmol/l of NACA to be used in our further in vitro experiments. CRAd-S-pk7 was toxic to HB1.F3.CD cells in a dose-dependent fashion. As shown in Figure 1a, viability of the NSCs was reduced by 13% at the dose of 5 IU/cell, 27% at 10 IU/cell and about 53% when NSCs were infected by 50 IU at 72 hours postinfection. Of note, we observed an increased viability of NSCs when 50 IU of CRAd-S-pk7 was combined with 1 mM of NACA as compared with other combinations (1, 5, and 10 IU of OV per cell). NACA combined with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU) increased the viability of NSCs 48 hours post-treatment. Moreover, treatment with 10 IU of CRAd-S-pk7 and NACA showed an enhanced viability of NSC carriers 96 hours post-treatment as compared with CRAd-S-pk7-loaded NSCs alone (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) prevents the apoptosis of NSC carriers loaded with CRAd-S-pk7. (a) HB1.F3.CD NSCs were treated with various concentrations of NACA (1, 2.5, 5, and 10 mmol/l), CRAd-S-pk7 (1, 5, 10, and 50 IU) and the combination of NACA with CRAd-S-pk7. Cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay 72 hours after treatment. Representative digital microscopic image of viable cells are seen in the bottom of Figure 1a. Scale bar, 200 μm. (b) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 at 10 and 50 IU/cell. Media was changed 1 hour after virus infection and then exposed to 1 mmol/l of NACA or were left untreated. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay at the indicated times. (c) The viability of U87 glioma cells after treatment with NACA and CRAd-S-pk7 was determined by MTT assay at 72 hours. The values shown are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control.

To further evaluate the effects of NACA combination with OVs on glioma cell viability, we infected U87 cells with various concentrations (1, 10, and 50 IU/cell) of CRAd-S-pk7 and measured the viability of cells after treatment with NACA via trypan blue exclusion. We have previously shown that several glioma cell lines were susceptible to CRAd-S-pk7 cytotoxic effects at concentrations over 10 IU/cell.11 We found that, by contrast with NSCs, the combination of NACA and OV did not show an enhanced viability of U87 cells (Figure 1c). Therefore, our data suggest that low-dose NACA, which has no cytotoxic effect in NSCs, enhances the viability of OV-loaded NSCs and does not increase the viability of U87 cells.

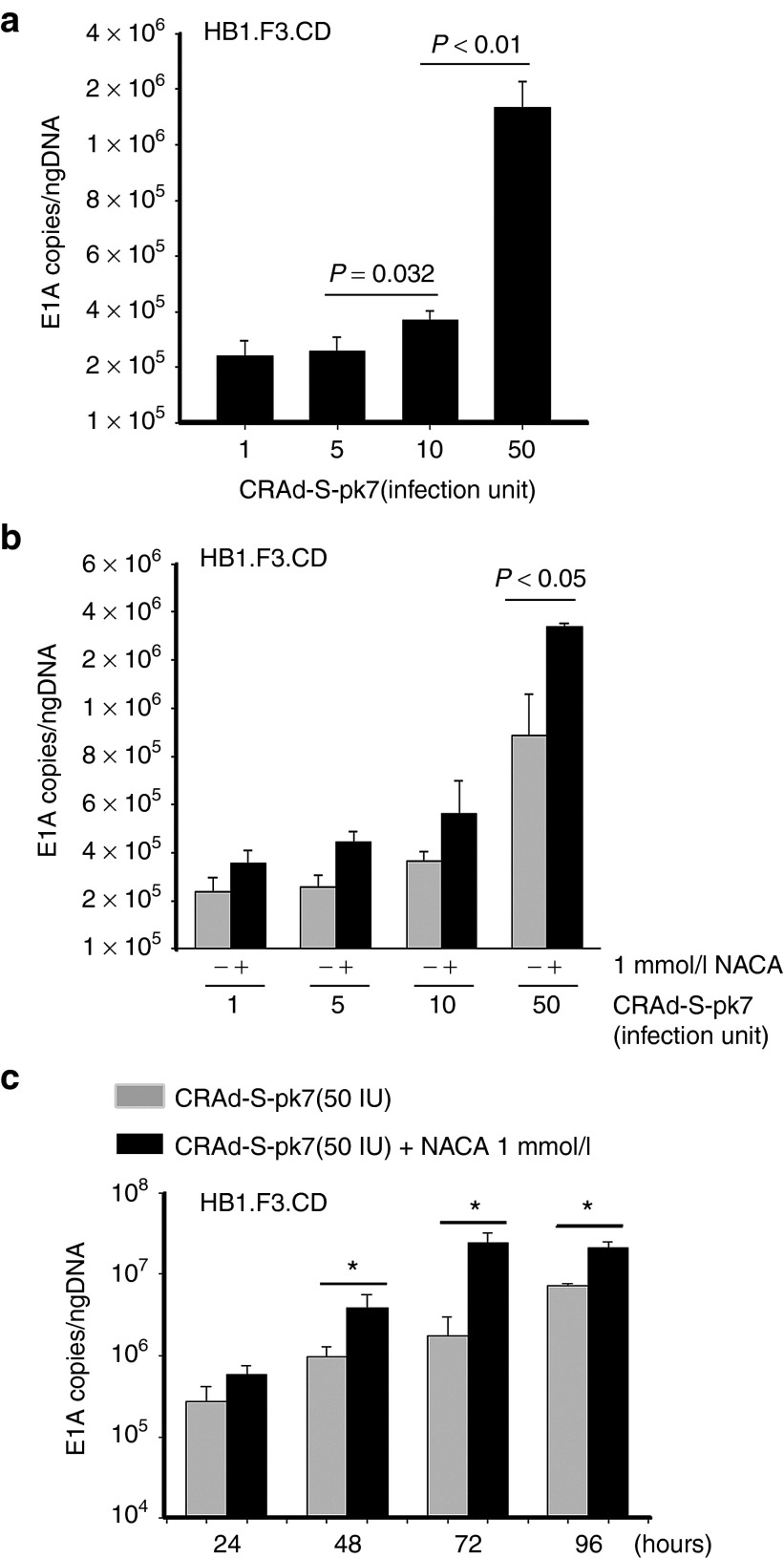

NACA treatment of CRAd-S-pk7-loaded NSCs increases viral replication and production of viral progeny

Our previous study demonstrated that DNA replication of CRAd-S-pk7 in stem cell carriers was highest at day 3 when cells were infected with 50 IU/cell of OVs. However, this same study showed that, although virus replication reached its peak, the viability of NSCs was decreased at this dose.12 Therefore, in order to determine the replication kinetics of CRAd-S-pk7 in NSCs treated with NACA, we conducted quantitative real-time PCR analysis to check the expression of the adenoviral E1A gene at 72 hours after treatment. As shown in Figure 2, when compared with the infection of OV alone, viral DNA replication was significantly increased when NSCs loaded with OV at a concentration of 50 IU/cell (1.78 × 106 E1A copies/ng DNA) were treated with NACA. Combination of 50 IU of OV loaded into NSCs treated with 1 mmol/l of NACA showed a 4.2-fold increase in viral replication compared with OV single treatment (P = 0.024) (Figure 2b). Contrarily, other combinations with various concentrations of CRAd-S-pk7 (1, 5, and 10 IU/cell) and 1 mmol/l of NACA showed little improvement of viral replication in NSCs as compared with the single treatment (P > 0.05). Time course treatment of CRAd-S-pk7 with 1 mmol/l of NACA demonstrated that virus replication had significantly increased from 48 to 96 hours after treatment as compared with OV single treatment. The highest effect (about a log) was observed at 72 hours postinitial therapy (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) treatment on CRAd-S-pk7 loaded HB1.F3.CD cells increases viral replication. HB1.F3.CD cells (5 × 104 cell/well) were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 at a concentration of 50-infection units/cell. Infected cells were then treated with/without NACA. Total DNA was isolated and the replication capacity of CRAd-S-pk7 combined with NACA was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Viral replication was determined by the number of viral E1A copies per ng of DNA from infected NSCs. All samples were analyzed in triplicates. They are presented as mean ± SEM. (a) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 in a dose-dependent manner (1, 5, 10, and 50 IU/cell) and (b) then combined with 1 mmol/l of NACA at 72 hours after treatment. (c) The replication of CRAd-S-pk7 treated with 1 mmol/l of NACA was measured by qRT-PCR in a time-dependent manner.

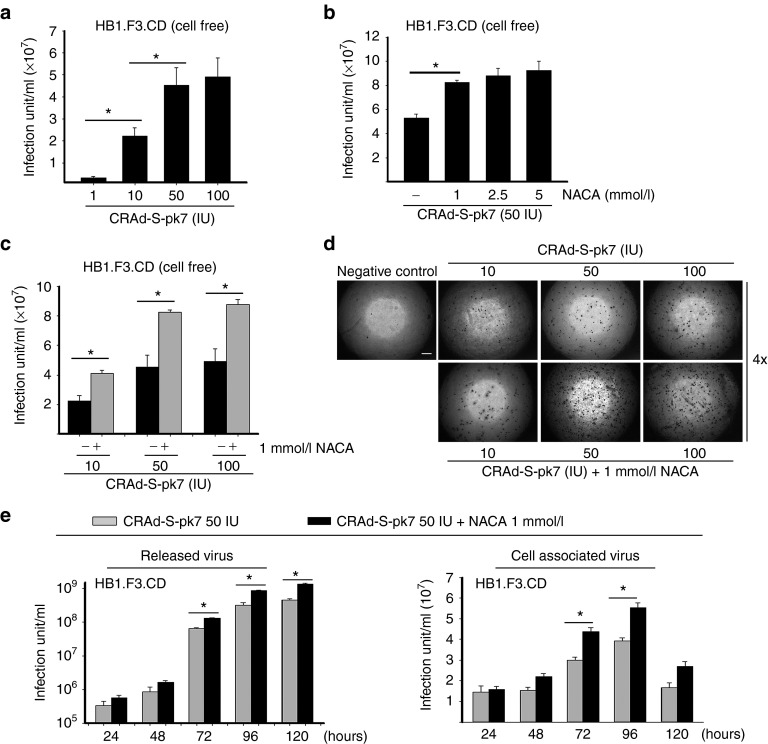

To evaluate viral production in NSC carriers treated with NACA, we performed a viral titer assay. We found that the production of CRAd-S-pk7 viral progeny in HB1.F3.CD cells increased in a dose-dependent manner. At 50 IU of CRAd-S-pk7 per cell, the viral production was about twofold higher than in the infection dose of 1 and 10 IU/cell, respectively (Figure 3a). However, we observed that CRAd-S-pk7 infection in the concentration of 100 IU/cell did not show an enhanced viral production as compared with 50 IU/cell. Then, we assessed viral release from NSCs treated with various concentrations of NACA (1, 2.5, 5 mmol/l) and a single concentration of OV (50 IU/cell). NSCs were harvested and subjected to total viral titer evaluation after 3 days of incubation. As a result, NSCs loaded with 50 IU/cell of OVs treated with 1 mmol/l of NACA presented a significant increase (61%) in OV release as compared with the untreated carriers (Figure 3b). NSCs treated with 2.5 and 5 mmol/l of NACA did not present a significant increase in viral release as compared with NSCs treated with 1 mmol/l of NACA.

Figure 3.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) enhances CRAd-S-pk7 viral production in HB1.F3.CD NSCs. (a) Media of HB1.F3.CD cells infected with various concentrations of CRAd-S-pk7 (1, 10, 50, and 100 IU/cell) were collected at 72 hours after treatment and assessed by viral titer assay. (b) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with 50 IU/cell of CRAd-S-pk7 and treated with different concentrations of NACA (1, 2.5, and 5 mmol/l). Viral titer was then evaluated. (c) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with several doses of CRAd-S-pk7 and subsequently treated with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA. Three days after treatment, supernatant was collected and viral titer assay was performed. (d) Representative microscopic pictures of viral titer assay. Scale bar, 200 μm. (e) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 at 50 IU/cell with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA. Supernatant (cell free) and the infected cells (cell associated) were separately collected at indicated time points. Viral titer was then analyzed.

Next, we assessed the release of OV progeny in NSCs treated with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA and loaded with different doses of CRAd-S-pk7 OVs (10, 50, and 100 IU/cell). The supernatant of infected cells was harvested 3 days postinfection. We observed that HB1.F3.CD cells released a significantly higher amount of viruses in each combination of OV and NACA. The observed increase in viral release was about 2–2.5-fold larger than that observed in cells infected with OV alone (Figure 3c, d). In order to determine replication and viral release in a time-dependent fashion, we infected NSCs with 50 IU/cell of CRAd-S-pk7 and harvested cells and supernatant separately at indicated times. As shown in Figure 3e, the combination of OV and NACA showed additive effects in both groups of released virus and cell associated virus as compared with OV only after 72 hours postinfection. Free viruses that were collected in the supernatant of NSCs treated with NACA maintained active replication for 5 days post-collection. In the cell associated virus group (NSCs infected with OVs that were collected apart from the supernatant), virus replication was higher at 96 hours post-treatment, and then it significantly decreased at day 5 due to cell death as a result of viral toxicity. Taken together, these data indicate that NACA significantly induces virus replication in NSCs loaded with oncolytic vectors and enhances the release of their associated viral progeny.

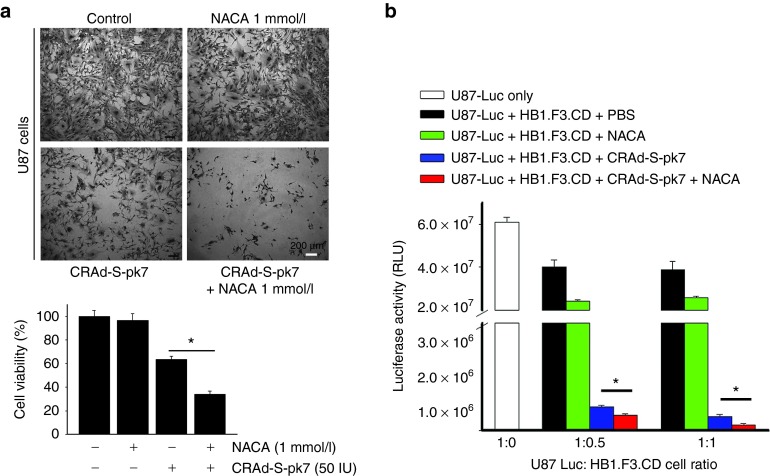

NACA treatment of NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 leads to increased production of infectious viral progeny and induction of glioma cell oncolysis

We examined the capacity of the viral progeny released from NSCs to lyse targeted tumor cells. Previously, we have shown that NSCs were permissive to CRAd-S-pk7 infection and replication.21 To assess if NACA treatment would affect the release of viral progeny from NSCs loaded with OVs and its related toxicity to glioma cells, we collected the supernatant containing the viral progeny released from infected NSCs treated or not with NACA. We then used trypan blue exclusion and crystal violet assay to measure CRAd-S-pk7-related toxicity toward U87 glioma cells 96 hours postinfection. Figure 4a shows a representative image demonstrating U87-related cytotoxicity as a result of CRAd-S-pk7 infection alone or combined with NACA treatment. Here, U87 cells treated with NACA alone and U87 mock cells were used as a control. As shown in Figure 4a, CRAd-S-pk7 viral progeny released from NSCs treated with NACA promotes a significantly higher lysis of glioma cells (73% toxicity) as compared with the treatment with CRAd-S-pk7 alone (38% toxicity). To further assess the cytotoxic effects of OV therapy combined or not with NACA on glioma cell viability, we performed a coculture experiment using U87 cells tagged with Luciferase report (U87-Luc) and HB1.F3.CD NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 OVs. First, NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell) were plated in a 96 well plate in two concentrations: 2,500 and 5,000 cells/well. Then, U87-Luc cells were plated onto the precultured wells at concentrations of 1 U87:0.5 NSCs and 1 U87:1 NSC. Cocultured cells in both conditions were incubated for 6 days, when glioma cells were collected, lysed, and luciferase activity was measured by luciferase assay (Promega). We found a decreased luciferase activity in U87-Luc cells infected with CRAd-S-pk7 treated with NACA as compared with the infected U87-Luc cells that did not receive NACA (Figure 4b). This means that U87-Luc cells infected with CRAd-S-pk7 presented a higher cytotoxicity when compared with its control without NACA. Moreover, noninfected U87 cells treated with NACA presented lower rates of cell lysis as compared with its mock control (U87 cells alone). Taken together, the above-described results demonstrate that NACA may effectively improve the therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic virotherapy and thereby enhance glioma oncolysis.

Figure 4.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) treatment of NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 leads to induction of glioma cell oncolysis. (a) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell) and then treated with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA. Supernatant was collected 4 days after initial treatment and used to infect U87 glioma cells. Cell viability was analyzed 4 days later using crystal violet staining (top). Scale bar, 200 μm. Differences in U87 cell viability between CON (control), NACA only, CRAd-S-pk7 only and OV and NACA combination groups were quantified (bottom). (b) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell) and then treated with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA. U87-Luc cells were plated in precultured wells containing NSCs loaded with OVs at the following ratio (NSCs: U87-Luc, 1:0.5 and 1:1). NSCs and U87 cells were lysed at 96 hours after coculture and Luciferase activity was measured. Bar graph shows luciferase activity (arithmetic mean ± SEM) in quadruplicates for each coculture. *P < 0.05.

NACA modulates endogenous ROS and decreases the expression of markers of cellular apoptosis in NSCs infected with CRAd-S-pk7

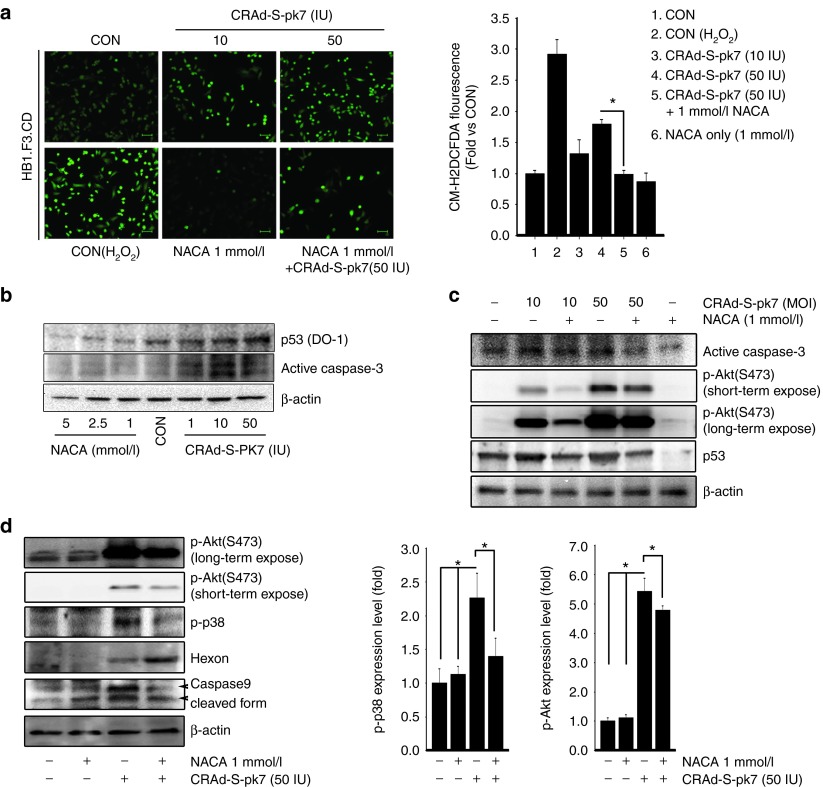

Previous studies have demonstrated that the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was closely related to the activation of proinflammatory pathways that happened as a response to viral infection.22 Other reports have also correlated the generation of ROS with the promotion of cellular transformation and tumorigenesis through DNA oxidation and subsequent gene mutation.23 Recently, a couple of additional studies have shown that cellular infection with OVs resulted in the accumulation of endogenous ROS in microglia and monocytic leukemia cells. Such an accumulation was able to induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and mitochondrial dysfunction in the host cell.24,25 Based on these findings, we set out to investigate the mechanisms underlying OV-mediated ROS accumulation in NSC carriers. To answer this question, we first checked if OV infection would be able to affect endogenous ROS levels in stem cell carriers. As shown in Figure 5a, HB1.F3.CD cells infected with CRAd-S-pk7 presented ROS accumulation in a dose-dependent manner. The combined treatment with NACA, however, effectively decreased endogenous ROS levels that were activated by cellular loading with oncolytic viruses. An interesting finding was that noninfected NSCs that were used as a control inherently expressed high levels of intracellular ROS. Such overexpression was decreased by NACA treatment.

Figure 5.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) modulates endogenous ROS and decreases the expression of markers of cellular apoptosis in NSCs infected with CRAd-S-pk7. (a) HB1.F3.CD cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 (10 and 50 IU/cell) and then treated with or without 1 mmol/l of NACA for 24 hours. Afterwards, cells were incubated with an oxidant-sensitive fluorogenic reagent, CM-H2DCFDA. Cell image was obtained using a fluorescent microscope. Scale bar, 100 μm. The mean fluorescence of four randomly selected fields was calculated. ROS values were compared with the control group and expressed as the fold of the control level. (b) HB1.F3.CD cells were treated with NACA (1, 2.5, and 5 mmol/l) and CRAd-S-pk7 (1, 10, and 50 IU/cell). After 24 hours, cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (c) HB1.F3.CD cells were treated with combination of NACA and CRAd-S-pk7 as indicated and cells were collected. Cell lysates (30 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with p-Akt, p53 and caspase-3 antibodies. (d) HB1.F3.CD cells were treated with combination of NACA (1 mmol/l) and CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell) and subjected to western blotting. Equal protein loading was verified by anti-β-actin antibody. The quantitative analysis of p-p38 and p-Akt protein levels was determined by densitometry analysis (normalized to actin), represented as a bar graph.

It has been previously shown that ROS accumulation in NSCs can lead to a number of different outcomes, such as decreased cellular proliferation and H2O2-induced apoptosis.26 Therefore, we examined by immunoblot assay NACA's antiapoptotic and proproliferative effects on NSCs loaded with OVs. We found that NSCs loaded with OVs presented an increased expression of proapoptotic genes (p53 and caspase-3) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5b). Infected NSCs treated with NACA, however, presented a significant decrease in p53 and caspase-3 expression. In connection with the signaling pathways related to proapoptotic stimuli, a recent report showed that ROS-dependent activation of Akt, Erk1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases in NSCs was associated with decreased self-renewal and proliferation.26 Based on this information, we set out to investigate if NACA treatment was able to prevent OV-induced increase in the intracellular levels of ROS through inhibition of p-Akt and p-p38 signaling pathways. We observed that NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 treated with NACA presented decreased activation of Akt and p38 pathways and reduced expression of apoptosis-related genes (p53, caspase-9 and caspase-3) (Figure 5c,d). We also found that the combination of CRAd-S-pk7 and NACA induced a higher expression of the adenovirus late protein (Hexon) as compared with OV alone. Hence, our results suggest that NACA effectively reduces the levels of apoptosis-related proteins as well as downregulates PI3K (phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase) and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling pathways in CRAd-S-pk7 loaded NSCs through modulation of intracellular ROS.

The combination therapy of NACA and CRAd-S-pk7-loaded NSCs prolongs mice survival in an orthotopic glioma model

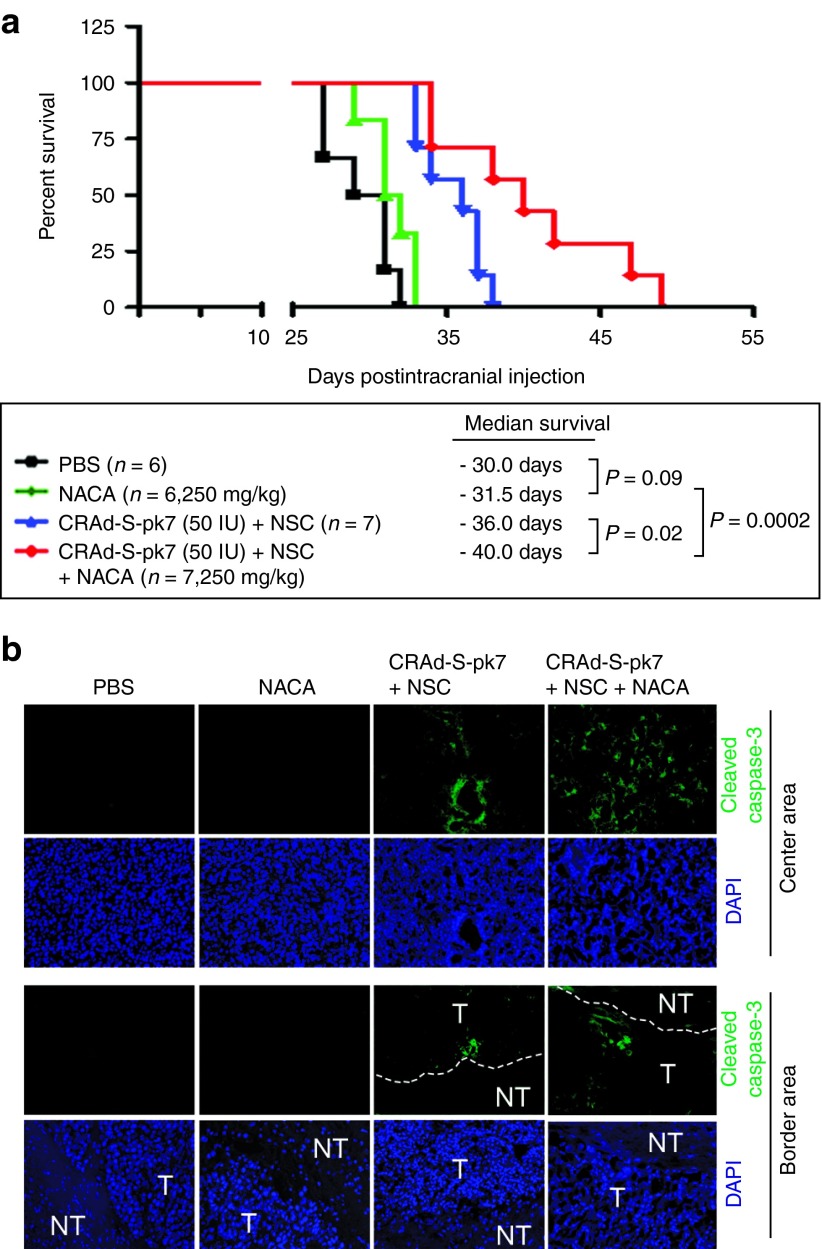

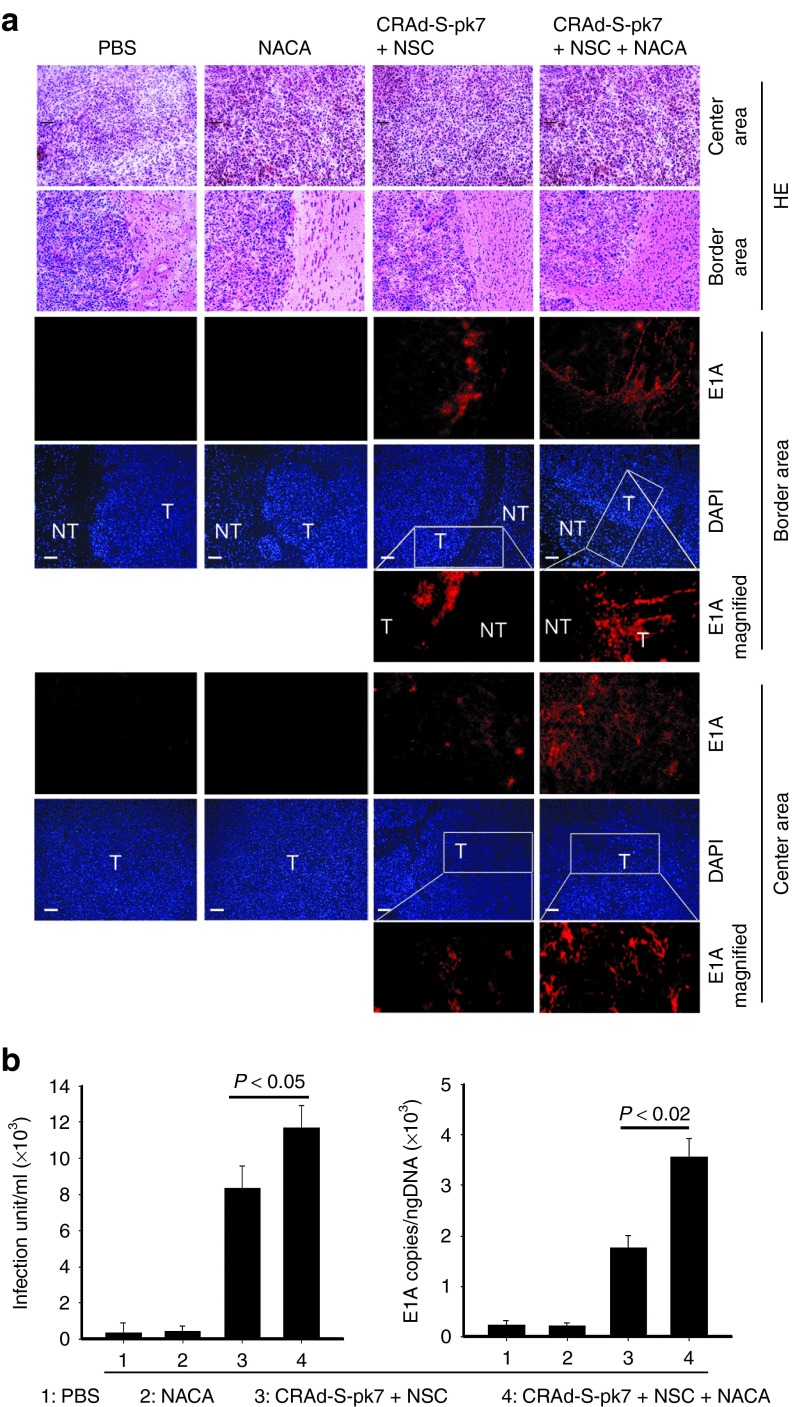

As a lipophilic drug, NACA has the striking advantage of crossing the blood–brain barrier.17 Based on this finding, the antioxidant and neuroprotective properties of NACA have been tested in many neurodegenerative diseases.27,28 Our lab has previously shown that NSCs could be used as delivery vehicles in order to enhance the antiglioma therapeutic efficacy of OVs in vivo.11,12 Therefore, we set out to evaluate if NACA treatment was able to increase the therapeutic efficacy of NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 OVs in a glioma xenograft model. U87 cells were then implanted in the brain of nude mice. Four days after tumor implantation, mice were divided into four groups: (i) control group, without treatment; (ii) NACA alone group; (iii) NSCs loaded with OV group; and (iv) NSCs loaded with OV in mice systemically treated with NACA. Groups ii and iv received NACA intraperitoneally 4 days post-tumor implantation, in the concentration of 250 mg/kg/day for 5 days. Groups iii and iv received NSCs (4 × 105 cells/animal) loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell) intratumorally also 5 days after tumor implantation. We found that mice treated with the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with OVs presented a significantly higher survival (median survival of 40 days) than mice treated with NSCs loaded with OVs alone (median survival of 36 days) (Figure 6a). NACA treatment alone, however, did not improve animal survival (median survival of 31.5 days) as compared with the PBS control group (median survival of 30 days). An important finding was that tumors treated with the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 presented an increased expression of proapoptotic markers such as caspase-3 as compared with NSCs loaded with OV alone (Figure 6b). One of the main advantages of using NSCs loaded with OVs is their ability to penetrate the tumor and reach infiltrative neoplastic areas. To evaluate if NACA treatment would affect NSC migration and intratumoral viral distribution in vivo, we examined the expression of an early-phase protein that drives viral genome replication (E1A) in tumor sections. Mice were sacrificed 21 days after tumor implantation, their brains were collected and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis using adenoviral E1A antibody. As shown in Figure 7a, tumors treated with the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 showed a significant increase in the expression of E1A viral protein as compared with the mice treated with NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 alone. We also observed that viral E1A protein was widely spread throughout the tumor in the combination group (group 4) as compared with the NSCs plus CRAd-S-pk7 group (group 3). As we repeated this same experiment twice, on the second time, we collected and dissociated mice brains. Then, we used quantitative real-time PCR analysis to assess the amount of viral DNA and viral progeny in vivo. We found a significant increase in CRAd-S-pk7 viral E1A and progeny in the NACA combination group as compared with the OV-loaded NSCs group (Figure 7b). Taken together, these data indicate that NACA enhances the therapeutic efficacy of CRAd-S-pk7 loaded NSCs by increasing intratumoral apoptosis and improving viral distribution in intracranial glioma xenografts.

Figure 6.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) combined with CRAd-S-pk7 loaded NSCs prolongs animal survival and increases intratumoral apoptosis. U87 cells (2 × 105 cells per mice) were intracranially injected into nude mice. Four days post tumor implantation animals were intraperitoneally treated with NACA, 250 mg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days. HB1.F3.CD cells incubated with CRAd-S-pk7 oncolytic virus (50 IU/cells) were resuspended in 1X PBS (4 × 105 cells in 2.5 μl/mouse) before intratumoral injection. NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 were intratumorally injected five days after U87 tumor implantations. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of mice implanted with U87 cells that were randomly divided into four groups: PBS (n = 6), NACA only (250 mg/kg, n = 6), HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell, n = 7) and combination of NACA and HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 (n = 7). Differences between survival curves were compared using a log-rank test and are shown as P values. *P < 0.05 (b) Histological sections of U87 brain tumors were stained with anticaspase-3 antibody. Dotted lines indicate the border between tumor (T) and nontumor (NT) areas.

Figure 7.

N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) treatment of CRAd-S-pk7 loaded NSCs enhances viral replication and increases viral progeny in vivo. Animals treated with the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 oncolytic viruses were sacrificed 21 days post-tumor implantation. Mice brains were collected, sliced into serial coronal sections, and the presence of CRAd-S-pk7 at both normal brain and tumor areas was analyzed by immunohistochemistry staining. (a) Immunohistochemistry staining showing E1A expression in U87 tumor sections (center and border) of mice treated with PBS, NACA only, HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with NACA and combination of NACA and HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with NACA. Scale bar, 35 μm. (b) The right brain hemisphere (the one with implanted tumor cells and intratumoral injection of NSCs) of mice from all four groups (n = 4 per group) was collected and in vivo CRAd-S-pk7 replication was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR. Viral progeny was assessed by viral titer assay.

Discussion

Despite the existence of advanced therapeutic strategies to treat GBM patients, their mean overall survival has little improved over the past decades.29 Also, the currently available treatment options that are effective for GBM patients are extremely limited. Therefore, it is undeniable that these patients are in need of novel and more effective therapeutic approaches. Oncolytic virotherapy using NSCs as carriers is one of the most promising areas of advancement.

A number of studies have shown that antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy has a prominent potential. However, the application of such strategy in clinical trials is still limited due to elevated production of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α that elicit the innate immune response against viral infection.30,31,32 During the last decade, our laboratory has been trying to develop targeted antiglioma therapies using stem cell carriers as delivery vehicles of OVs and drugs. Recently, we reported that NSCs loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 suppressed antiadenoviral immune response and enhanced antiglioma therapeutic efficacy as compared with CRAd-S-pk7 treatment alone.11,33 We have focused on two specific concerns for improving the therapeutic efficacy of OV-loaded NSCs against malignant gliomas. The first is protecting NSC carriers from oncolytic virus-mediated toxicity, and therefore improving their viability, increasing oncolytic virus replication, and enhancing their tumor homing capacity. The second one is how to increase viral replication in cell carriers without increasing toxicity. In this report, we evaluated the effectiveness of the combination of an antioxidant drug (NACA)- and OV-loaded NSCs in antiglioma therapy. Our goal was to improve the migration efficiency of NSCs and the production of viral progeny by inhibiting apoptosis of the cell carriers. Our results demonstrate that NACA inhibits ROS-mediated apoptosis of NSCs and extends median survival of mice with brain tumors by enhancing the production of viral progeny in NSC carriers. This suggests that NACA may be an effective candidate to improve the antiglioma therapeutic efficacy of NSCs loaded with OVs.

It has been previously shown that the intracellular increase of ROS levels activates MAP kinases, c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) and MAPK (p38), which promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death.34 By contrast to normal cells, high levels of ROS have been reported in most of the cancer cells. This implies an important role of ROS as a second messenger in cancer proliferation.35 NACA, a modified form of NAC, is a free radical scavenger with antiapoptotic properties and greater cell permeability.17 Most of the in vitro studies assessing the efficacy of NAC against cancer cells infected with OVs have demonstrated increased viral replication and inhibition of glioma cell proliferation.19,20 Nevertheless, because NACA is able to cross the blood–brain barrier, it has been considered a better option to target brain cancers. Recent reports have shown that OV infection enhances the accumulation of intracellular ROS in the host cell, and activates p38 and ERK1/2 MAPKs in microglia cells. When compared with other viruses, infection with adenovirus type 5 has led to a greater intracellular production of ROS.24,25 It has been suggested that NSCs may maintain low levels of ROS in order to avoid apoptosis.36 High levels of ROS in NSCs carriers generated by virus infection are detrimental to an effective stem cell migration, viral replication and payload delivery. In order to overcome this problem, we set out to evaluate the efficacy of NACA as an antioxidant in order to decrease the intracellular levels of ROS in NSCs loaded with OVs. Indeed, we found that NSCs infected with OVs not only accumulated endogenous ROS and overexpressed proapoptotic proteins such as p53 and caspase-3, but also markedly activated Akt and p38 protein levels. The treatment of NACA significantly decreased p-Akt and p-p38 proteins, reduced intracellular levels of ROS, and therefore inhibited CRAd-S-pk7-induced apoptosis of NSCs. We also observed that NACA antiapoptotic effects were able to enhance the viability of NSC carriers, increase intracellular virus replication and increase even intratumoral payload delivery. Our data indicates that NACA, as an ROS scavenger, is a promising candidate to help to augment the production of effective viral progenies by preventing ROS-induced apoptosis of NSCs loaded with OVs.

In general, systemically administered OVs are quickly eliminated by the innate immune response before they are able to reach the target tumor site.37 Previous reports demonstrated that NSCs not only have the capacity to migrate towards tumor areas, but they also possess immunosuppressive properties.38,39 Regarding the ability of NSCs to deliver OVs, we have reported that NSCs loaded with OVs were able to increase viral distribution, suppress antiviral innate immune responses, and extend animal median survival by 50% as compared with oncolytic virotherapy alone.11,21 Although only 20–30% of the NSCs contralaterally injected in the mouse brain were able to migrate to the targeted glioma area, the therapeutic effect was considered significant.11 In order to investigate if NACA treatment could increase the in vivo viability of NSC carriers, enhance viral replication and improve therapeutic efficacy, we performed an in vivo analysis of the antitumor effects of the combination of NACA plus NSCs loaded with OVs on the survival of mice bearing intracranial gliomas. We found that NACA combination therapy significantly prolonged mice overall survival and promoted even intratumoral viral distribution as compared with the NSCs loaded with OVs alone. Based on our findings, we propose that, by inhibiting the apoptosis of NSCs, NACA could enhance the production of OVs in cell carriers, and improve their payload delivery to targeted tumor sites. This would consequently improve the therapeutic efficacy of NSC-based oncolytic virotherapy against malignant gliomas in vivo.

The present study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. As nude mouse models are immune suppressed, immune response was not evaluated in this report. In addition, it has been demonstrated that NACA plays a critical role in the modulation of ROS therefore regulating cancer progression. However, the mechanisms behind this regulation remain to be determined. In conclusion, our results provide the first direct evidence that an ROS scavenger, NACA, can enhance the production of OVs in NSC carriers by avoiding cellular apoptosis, which results in extended animal survival in an orthotopic glioblastoma model. Therefore, the combination of NACA and NSCs loaded with OVs may be a novel and desirable therapeutic strategy to treat malignant gliomas.

Considering the properties of NSCs, which includes maintenance of inherent tumor tropism, permissiveness to viral infection and protection of virus from the host immune surveillance, NSC-based oncolytic virotherapy seems to be an attractive therapeutic strategy against malignant glioma. Our study enhances the practical aspect of the stem cell-based oncolytic virotherapy. Once the clinical application of NSCs loaded with OV for malignant gliomas is accepted, concomitant treatment with NACA, via parenteral or oral route, should be tried in order to maximize the NSC's role as a viral carrier.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, antibodies, and viruses. U87 (purchased from the ATCC, Manassas, VA) and U87-Luciferase-neomycin (U87-LucNeo) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawerenceville, GA) and 100 units of penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. HB1.F3.CD is a v-myc-immortalized human NSC (hNSC) line, derived from the human fetal brain that constitutively expresses cytosine deaminase (CD). HB1.F3.CD cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/l l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B. Anti-p53 (DO-1), actin and active caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti phospho-Akt, phospho-p38 and caspase-9 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-Hexon antibody was purchased from the Abcam. Human CRAd-Survivin-pk7 (CRAd-S-pk7) was propagated as described previously,8,40 and NACA was provided by Dr. Glenn Goldstein (David Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY).

Cell viability assay. HB1.F3.CD and glioma cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cells) for 1 hour followed by washing with PBS twice. Infected cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were plated onto a 96-well plate and further incubated using the complete medium with/without NACA (1 mmol/l) in a dose- and time-dependent manner. 10 µl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide was added into each well followed by incubation at 37°C for 4 hours. Finally, 100 µl of solubilization buffer was added. The plate was incubated at 37°C overnight, and light absorption was measured at a 595 nm wavelength. Cell viability was also evaluated by trypan blue exclusion method using the Bio-Rad automated cell counter (TC10). Each value from these indicated assays represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments.

Analysis of viral replication and progeny. For quantitative PCR analysis of adenoviral E1A gene expression, HB1.F3.CD cells (5 × 104 cell/well) were plated in 6-well culture dishes. On the next day, plated cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 at the indicated infection unit per cell for 1 hour and then carefully washed with PBS following the addition of fresh complete media with/without NACA. Total DNA from cultured cells (or animal brain tissue) was extracted at designated time points using DNeasy Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was quantified using NANO drop and was subsequently used for quantitative real-time PCR with iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Sequences of primers for detection of the E1A gene were the following: forward, 5′-AACCAGTTGCCGTGAGAGTTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCGTTAAGCAAGTCCTCGATACAT-3′. DNA amplification was carried out using an Opticon 2 system (Bio-rad, CA). All samples were run in triplicates and results were shown as the average number of E1A copies/ng of DNA.

To investigate the production of viral progeny in NSCs infected with CRAd-S-pk7 and then treated with or without NACA, HB1.F3.CD cells were seeded at a concentration of 50,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS. Twenty-four hours after incubation, cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 at several infection units per cell and further incubated for 1 hour. Then, virus-containing media were removed, cells were washed with 1X PBS, and fresh complete media with/without NACA was added. After incubation for an indicated time, supernatant as well as cells were collected separately. Collected cells were suspended in 200 µl of 1X PBS and were lysed by freezing and thawing three times. Lysed cells were incubated in 80% confluent HEK293 cells at a serial 10-fold dilution condition. Forty-eight hours after incubation, viral titer (infection units per milliliter) was determined by Adeno-X Rapid Titer Kit (Clontech, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis of glioma cell cytotoxicity by viral progeny released from NSCs. To evaluate the cytotoxic effect of oncolytic viruses released from NSCs toward glioma cells, HB1.F3.CD cells (5 × 104 cell/well) were plated in 6-well culture dishes. Cells were infected with CRAd-S-pk7 (50 IU/cell). One hour after incubation, cells were carefully washed with prewarmed 1X PBS twice and then fresh complete media with/without 1 mmol/l NACA was added. After 4 days, supernatant and infected U87 cells (5 × 104 cell/well in 6-well plates) were secured. The viability of glioma cells was determined by 0.25% crystal violet staining for 20 minutes at room temperature. Stained cells were visualized with an inverted microscope and counted (20X magnification).

Luciferase assay (coculture). For determination of virus-mediated cytotoxicity, HB1.F3.CD cells infected with CRAd-S-pk7 were plated in 96-well culture plates at a cell density of 2,500 (U87-Luc and HB1.F3.CD cell ratio = 1:0.5) or 5,000 (U87-Luc and HB1.F3.CD cell ratio = 1:1) cells/well and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. CRAd-S-pk7-permissive U87 cells were used as a positive control for adenoviral replication and virus induced cytopathic effect. Four hours later, U87-Luc cells (5 × 103 cells per well) were plated in HB1.F3.CD-cultured plates and further incubated for 6 days. Luciferase activity was performed using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the provided protocol. Corresponding firefly luciferase reporter activity was used for normalization.

Determination of ROS generation in NSCs. Endogenous ROS generation in NSCs was accessed by staining cells with 5-(and-6) chlolomethyl-2′,7′-dichlorfluorescein-diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, HB1.F3.CD cells were incubated in 6-well plates for 24 hours. After infecting cells with or without CRAd-S-pk7 (10 or 50 IU) for 1 hour, cells were washed with fresh 1X PBS twice followed by the addition of complete media with/without 1 mmol/l NACA. After 48 hours, cells were incubated with 10 µmol/l CM-H2DCFDA in serum-free media at 37°C for 30 minutes according to manufacturer's instruction. H2O2 treatment was used as a positive control. Cells were treated with 50 µmol/l H2O2 before staining with CM-H2DCFDA. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and images were captured with fluorescence microscope. Three fields from each of the three separate wells were measured for each group. Fluorescence was quantified from 30 random cells in each image using NIH image J software.

Western blot analysis. HB1.F3.CD cells were incubated with various concentrations of CRAd-S-pk7 and/or NACA. Cells were washed and harvested in 1X PBS and subsequently lysed with lysis buffer (M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) supplemented with 10 mmol/l Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN)) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 30 µg of each cell lysate was used for SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Immunocomplexes were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Images were collected using a Bio-Rad image analyzer.

Animal experiments. The University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal studies and all procedures. The antiglioma therapeutic efficacy of the combination of OV-loaded NSCs and NACA was determined in an in vivo intracranial animal model. Briefly, 6-week-old athymic nude mice were housed in laminar-flow cabinets under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a ketamine/xylazine mixture (115/17 mg/kg), and were held in a stereotactic frame with an ear bar. After skin incision, a burr hole was made in the skull 1 mm anterior and 2 mm lateral to the bregma to expose the dura. U87 cells (2 × 105 cells in a volume of 2.5 µl of PBS) were slowly injected 3-mm deep into the brain with a Hamilton syringe. Four days after tumor implantation, the animals were randomly divided into four groups, and were intraperitoneally treated with NACA (250 mg/kg/day) continuously for 5 days. On the next day after NACA first treatment, mice received an intracranial or intratumoral injection of 4 × 105 HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with 50 IU of CRAd-S-pk7 oncolytic viruses. The four groups were: group 1 (PBS intraperitoneal, control, n = 6), group 2 (NACA, 250 mg/kg intraperitoneal, n = 6), group 3 (HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 50 IU, n = 7) and group 4 (NACA, 250 mg/kg intraperitoneal plus HB1.F3.CD cells loaded with CRAd-S-pk7 50 IU, n = 7). Neurological signs and body weight were checked every day during the treatment. Animals losing ≥30% of their body weight or having trouble ambulating, feeding, or grooming were killed by CO2 intoxication followed by cervical dislocation and the brains were removed. Midcoronal sections of the whole tumor were used for histological and immunohistochemical analyses.

Analysis of immunohistochemistry staining. Tumors were dissected from the sacrificed mice, fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution, and frozen in OCT compound in a dry ice–methylbutane bath. Frozen tissues were cut coronally at the injection site in two pieces and sectioned into 10-μm thick slices. Immunofluorescent stains were applied using monoclonal antibodies against caspase 3 and E1A. Brain sections were dry at room temperature and fixation/permeabilization was carried with 50/50 mixture of acetone-methanol. The tissues were three times washed with cold PBS and blocked with 10% BSA for 30 minutes. Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the secondary antibody. After washing with cold PBS three times, tissues were covered with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA). Images were acquired using an inverted Zeiss microscope.

Statistical analysis. Experimental data were analyzed for statistical significance using SigmaPlot, statistical analysis software (Systat Software) and GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All experiments were performed in a blinded manner. Survival curves were generated by Kaplan–Meier method, and log-rank test was used to compare the distributions of survival times. These data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was defined as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Glenn Goldstein (David Pharmaceuticals, New York) for providing N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA). We also thank Lingjiao Zhang for her expertise in the statistical analysis, and Yu Han for helping with the animal experiments. This work was supported by the NCI (R01CA122930, R01CA138587, K99 CA160775), the NIH (R01NS077388), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01NS069997), and the American Cancer Society (RSG-07-276-01-MGO). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Kornblith PK, Welch WC, Bradley MK. The future of therapy for glioblastoma. Surg Neurol. 1993;39:538–543. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krex D, Klink B, Hartmann C, von Deimling A, Pietsch T, Simon M, et al. German Glioma Network Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130 Pt 10:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese A, Westphal M. Glioma invasion in the central nervous system. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:235–50; discussion 250. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas MK, Lukas RV, Chmura S, Yamini B, Lesniak M, Pytel P. Molecular heterogeneity in glioblastoma: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:243–253. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumma SR, Elaimy AL, Daines N, Mackay AR, Lamoreaux WT, Fairbanks RK, et al. Long-term survival after gamma knife radiosurgery in a case of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:545492. doi: 10.1155/2012/545492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghi M, Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies - the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–7816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulasov IV, Zhu ZB, Tyler MA, Han Y, Rivera AA, Khramtsov A, et al. Survivin-driven and fiber-modified oncolytic adenovirus exhibits potent antitumor activity in established intracranial glioma. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:589–602. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulasov IV, Tyler MA, Zhu ZB, Han Y, He TC, Lesniak MS. Oncolytic adenoviral vectors which employ the survivin promoter induce glioma oncolysis via a process of beclin-dependent autophagy. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:729–742. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulasov IV, Sonabend AM, Nandi S, Khramtsov A, Han Y, Lesniak MS. Combination of adenoviral virotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy eradicates malignant glioma through autophagic and apoptotic cell death in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1154–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AU, Thaci B, Alexiades NG, Han Y, Qian S, Liu F, et al. Neural stem cell-based cell carriers enhance therapeutic efficacy of an oncolytic adenovirus in an orthotopic mouse model of human glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1714–1726. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaci B, Ahmed AU, Ulasov IV, Tobias AL, Han Y, Aboody KS, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of neural stem cell-based cell carrier for oncolytic virotherapy: targeted delivery of the therapeutic payload in an orthotopic brain tumor model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19:431–442. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JY, Pradarelli J, Haseley A, Wojton J, Kaka A, Bratasz A, et al. Copper chelation enhances antitumor efficacy and systemic delivery of oncolytic HSV. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4931–4941. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema TA, Kanai R, Kim GW, Wakimoto H, Passer B, Rabkin SD, et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of low-dose Etoposide with oncolytic herpes simplex virus in human glioblastoma stem cell xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7383–7393. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongara S, Karantza V. The interplay between autophagy and ROS in tumorigenesis. Front Oncol. 2012;2:171. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offen D, Gilgun-Sherki Y, Barhum Y, Benhar M, Grinberg L, Reich R, et al. A low molecular weight copper chelator crosses the blood-brain barrier and attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1241–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Celsi G, Carlsson K, Norgren S, Chen M. N-acetylcysteine amide protects renal proximal tubular epithelial cells against iohexol-induced apoptosis by blocking p38 MAPK and iNOS signaling. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:178–188. doi: 10.1159/000268161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín V, Herrera F, García-Santos G, Antolín I, Rodriguez-Blanco J, Rodriguez C. Signaling pathways involved in antioxidant control of glioma cell proliferation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1715–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanziale SF, Petrowsky H, Adusumilli PS, Ben-Porat L, Gonen M, Fong Y. Infection with oncolytic herpes simplex virus-1 induces apoptosis in neighboring human cancer cells: a potential target to increase anticancer activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3225–3232. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AU, Tyler MA, Thaci B, Alexiades NG, Han Y, Ulasov IV, et al. A comparative study of neural and mesenchymal stem cell-based carriers for oncolytic adenovirus in a model of malignant glioma. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:1559–1572. doi: 10.1021/mp200161f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink K, Duval A, Martel A, Soucy-Faulkner A, Grandvaux N. Dual role of NOX2 in respiratory syncytial virus- and sendai virus-induced activation of NF-kappaB in airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:6911–6922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Sheng WS, Schachtele SJ, Lokensgard JR. Reactive oxygen species drive herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by murine microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:123. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire KA, Barlan AU, Griffin TM, Wiethoff CM. Adenovirus type 5 rupture of lysosomes leads to cathepsin B-dependent mitochondrial stress and production of reactive oxygen species. J Virol. 2011;85:10806–10813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00675-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wong PK. Loss of ATM impairs proliferation of neural stem cells through oxidative stress-mediated p38 MAPK signaling. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1987–1998. doi: 10.1002/stem.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg L, Fibach E, Amer J, Atlas D. N-acetylcysteine amide, a novel cell-permeating thiol, restores cellular glutathione and protects human red blood cells from oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Banerjee A, Banks WA, Ercal N. N-Acetylcysteine amide protects against methamphetamine-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in immortalized human brain endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2009;1275:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorence RM, Rood PA, Kelley KW. Newcastle disease virus as an antineoplastic agent: induction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and augmentation of its cytotoxicity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:1305–1312. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.16.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora AL, Rizvi N, Cohen GI, Meropol NJ, Sterman D, Marshall JL, et al. Phase I trial of intravenous administration of PV701, an oncolytic virus, in patients with advanced solid cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2251–2266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WQ, Lun X, Palmer CA, Wilcox ME, Muzik H, Shi ZQ, et al. Efficacy and safety evaluation of human reovirus type 3 in immunocompetent animals: racine and nonhuman primates. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8561–8576. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AU, Rolle CE, Tyler MA, Han Y, Sengupta S, Wainwright DA, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells loaded with an oncolytic adenovirus suppress the anti-adenoviral immune response in the cotton rat model. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1846–1856. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhar M, Dalyot I, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. Enhanced ROS production in oncogenically transformed cells potentiates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and sensitization to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6913–6926. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6913-6926.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz P. Reactive oxygen species in tumor progression. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1881–1896. doi: 10.2741/1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan L, Ourednik V, Ourednik J. Increased “vigilance” of antioxidant mechanisms in neural stem cells potentiates their capability to resist oxidative stress. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2110–2119. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K. Striking out at disseminated metastases: the systemic delivery of oncolytic viruses. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2006;8:301–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass R, Synowitz M, Kronenberg G, Walzlein JH, Markovic DS, Wang LP, et al. Glioblastoma-induced attraction of endogenous neural precursor cells is associated with improved survival. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2637–2646. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino S, Zanotti L, Rossi B, Brambilla E, Ottoboni L, Salani G, et al. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–271. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AU, Ulasov IV, Mercer RW, Lesniak MS. Maintaining and loading neural stem cells for delivery of oncolytic adenovirus to brain tumors. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;797:97–109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-340-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]