Abstract

Objectives

In Bangladesh, second-hand smoke (SHS) is recognised as a principal source of indoor air pollution and a major public health problem. However, we know little about the extent to which people are aware of the risks of second-hand smoking, or restrict smoking indoors or in the presence of children. We report findings of a community survey exploring these questions.

Design and setting

A total of 722 households were surveyed in urban and rural settings, using a multistage cluster random sampling approach and a semistructured questionnaire. In addition, we used qualitative methods to further explore the determinants of smoking-related behaviours inside homes.

Findings

55% of households in our sample had at least one regular smoker. Smoking indoors was common. In 30% of households, smoking occurred in the presence of children, exposing nearly 40% of children to SHS. Overall, we found a lack of awareness about the harms associated with second-hand smoking.

Conclusions

Our study highlights that a sizeable proportion of children and non-smokers are exposed to SHS at homes in Bangladesh, posing a significant and grave public health problem. In the absence of any impetus to legislate against smoking in private places, an educational approach is recommended to change smoking practices at home. Such a shift toward voluntary smoking restrictions at home would require behaviour change among smokers and support from non-smoking family members.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health, Qualitative Research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first community survey on children's exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS), which uses the latest age parameter of children after Bangladesh has adopted United Nations standards to redefine the age of a child by raising it from 14 to 18.

By using quantitative and qualitative methods, this study gathers more insights, perceptions and myths about SHS and its harmful effects.

The study did not attempt to establish the association of exposure to SHS with any existing health conditions among children.

Introduction

Exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke poses a serious health hazard to non-smoking adults and children.1 2 Evidence suggests that exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) increases the lifetime risk of coronary heart disease by 25–30% and the risk of lung cancer by 20–30% in non-smokers.3 Öberg et al3 estimated that more than 600 000 deaths were attributable to SHS in 2004; 28% of these deaths occurred in children aged 5 years or under. Moreover, 61% of total disability-adjusted life years lost due to SHS were in children.3

There is no evidence of a safe level of exposure to SHS; even brief exposure can be harmful.3 For children, SHS exposure has consistently been linked to adverse health outcomes, such as smoke-caused coughs and wheezing, acute lower respiratory infections, exacerbated asthma, middle ear infections, meningococcal meningitis and sudden infant death syndrome.4––6 Exposure during childhood to SHS may also be associated with asthma and cancer during adulthood. Moreover, children exposed to SHS are more likely to become smokers themselves when they grow older compared to those unexposed.3 7

Although children are exposed to SHS in other places, the primary source of SHS exposure is in their homes.8 Globally, about 40% of children younger than 14 years of age are exposed to SHS within their homes—these estimates are much higher for low-income countries in the South-East Asia, Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions.3 9 In Bangladesh, about 45% of adults10 (definition >15 years) and 42% of youths (aged 13–15) are exposed to SHS in public places, while 63% of adults and 35% of youths are exposed to SHS in the workplace.10 11 Concerns have also been raised about potentially high levels of SHS exposure among children at household level; however, data are limited.

Bangladesh is a signatory to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which calls for measures to protect people from SHS.12 In 2007, the National Tobacco Control Cell (NTCC) unveiled a National Strategic Plan of Action to reduce SHS exposure among non-smoking adults and children.13 The priority objectives include measuring the extent of children's exposure to SHS within homes, and developing evidence-based interventions to reduce such exposure. However, slow progress in implementation of the plan means there has been no noticeable impact. Moreover, to date, research on SHS exposure among children in Bangladesh has been limited, and much more needs to be carried out to highlight this inadequately investigated threat to children. To contribute toward national efforts to protect children from harmful effects of SHS, we initiated a cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) in Bangladesh to develop and evaluate a ‘smoke-free homes’ intervention to reduce children's exposure to SHS at home.

As part of this cRCT, we conducted a community survey to determine the magnitude of children's exposure to SHS at the household level, and the extent to which people are aware of the risks of second-hand smoking. We also wanted to determine whether smokers observe any smoking restrictions at home. This article presents the findings of this survey.

Methods

Concepts and definitions

Children are categorised as those aged <18 years, as in the recent National Children Policy of Bangladesh.14 In the absence of a universal age limit to categorise children, previous studies have used different age limits for them.

Home refers to rooms and all enclosed spaces within the house; all outdoor spaces including balconies, verandas and rooftops are considered to be ‘outside’ the house.

SHS is defined as a mixture of side stream smoke from the end of a burning cigarette and exhaled mainstream smoke; second-hand smoking or exposure to SHS is unintentional inhalation of cigarette, cigar or pipe smoke by non-smokers.8 15 16

Smoking was defined as consumption of at least one cigarette/bidi (locally made rolled cigarettes)/cigar per day, or usage of pipe at least once a day.

A smoker is one who smokes cigarettes/bidi, cigars or pipes irrespective of the level of tobacco consumption.

If a person smoked inside the house in the presence of children, it was considered as smoking in the presence of children for this study. We considered people smoking outside the house, when they smoked on the balcony/veranda, courtyard, rooftop and/or on the road adjacent to house. This was considered as complete restrictions of smoking at home. Those who smoked anywhere in the house were considered having no restrictions of smoking at home. Those who smoked inside the house but only in a specified room with window open, was defined as maintaining partial restrictions at home.

Setting

We carried out our survey in two areas of Dhaka Division—Mirpur and Savar. These sites were purposively selected to geographically typify urban and rural contexts, respectively: Mirpur is situated within Dhaka Metropolitan City Corporation (DMCC), whereas Savar is a rural subdistrict located approximately 40 km outside DMCC. We selected these sites in light of the study objectives and pragmatic factors such as operational constraints, willingness of administrative authorities to be involved in the survey and locations of our research partners.

Study design and sampling

A mixed method design was employed. We used a cross-sectional household survey to assess smoking-related knowledge and behaviours, and in-depth interviews and focused group discussions (FGDs) in a subsample to identify perceived barriers and drivers in implementing smoking restrictions at home.

A multistage, stratified, cluster random sampling approach was adopted. Two wards from Mirpur and one ward from Savar were randomly selected. Households were stratified into three groups according to the types of housing: pucca (brick built) houses, semipucca houses and those in slums (urban) or thatched (rural). Households were selected according to the proportionate distribution of each stratum in the Mirpur and Savar wards. Assuming a tobacco smoking prevalence of 23%,10 and a design effect of 1.2, to account for any correlation within survey clusters, the minimum sample size needed to achieve a precision of ±6% was estimated to be 227 households from each ward. We thus planned to survey a minimum sample of 454 households in Mirpur, and 227 households in Savar.

Households were included only if they had a household head or any adult family member who was a permanent resident of the household. Visitors or temporary occupants were excluded. We excluded those households in which no adult respondents were present at the time of visit. Standard multihousehold selection procedures were used at addresses with those buildings having more than one household, to give each an equal chance of selection.

Data collection

Data on all family members were collected from each sampled household. We interviewed the household head using a pretested semistructured questionnaire.

The survey variables were derived from the objectives of the survey. Questions were asked on household composition; knowledge about SHS; smoking-related behaviours at home including smoking practices in the presence of children; application of any smoking restrictions at home and the extent of children's exposure to SHS. Respondents’ demographic characteristics including age and education were defined according to the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) protocol. We also explored whether interviewees had tried to make their home smoke free and what challenges they had faced while making such attempt.

Two fully trained and experienced field researchers conducted all household visits. The survey team was trained to interview the household head present at the address, but in the absence of the household head, one adult member was randomly selected. Informed consent was taken before participation.

Field researchers’ performances were strictly monitored. They were accompanied by a project supervisor during initial household visits to ensure correct administration of survey questionnaires. Routine validation and spot checks were conducted on at least 10% of questionnaires to ensure quality.

In addition, six FGDs were conducted—four in Mirpur and two in Savar—to triangulate survey findings. A ‘snowballing’ method—starting from a local health facility—was used to identify potential FGD participants and interviewees. Each FGD included 8–10 participants, representing different establishments of the local community such as schools, media, religious institutions, health facilities, local businesses, factories and farms; members of local women's groups and housewives were also included. FGDs were conducted to assess people's knowledge on adverse effects of SHS, explore potential ways of reducing SHS exposure to children and other non-smokers and identify possible challenges in implementing smoking restrictions at home.

Further information was obtained from in-depth interviews with five schoolteachers, four community leaders, four health workers and three non-governmental organisation (NGO) representatives from each study site. An interview guide was used to conduct interviews and FGDs.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS V.14.0 and Microsoft Excel. Qualitative data were analysed using a ‘mixed’ thematic approach with the identified themes deriving from predefined and emergent issues relevant to the study objectives. Notes from field researchers were compared and analysed systematically, generating initial codes and subsequently developing more conceptual and defined themes. Comparisons were made across interviews and FGDs and within themes to ensure analytical categories and emerging concepts were fully explored, and all viewpoints of each theme were considered. Six authors were involved in the analysis, with the coding framework and themes being agreed by at least two authors. All findings have been drawn to inform this article, with key concepts illustrated using anonymised quotes.

Ethics

Ethical principles including informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained.

Findings

Data were collected between May and August 2011. A total of 747 households met the inclusion criteria and were approached for the survey. Of those, 722 households (472 households in Mirpur and 250 in Savar) participated in the survey and 25 households (12 in Mirpur and 13 in Savar) were either excluded or refused to participate. On an average, one household survey took approximately an hour.

Demographic characteristics of the survey respondents

In Mirpur, the 472 households surveyed comprised 2118 family members with average family size of 4.5 members; in Savar, the 250 households surveyed comprised 1013 household members with average family size of 4.1. Forty-eight per cent of household members were women, and over a third of the surveyed population was under the age of 18–41% in Mirpur and 33% in Savar. The percentage of the population with education higher than Secondary School Certificate level was much higher in Mirpur than Savar. The occupation of respondents differed between areas: there were no unemployed people in Savar (rural) as family members remain engaged with their family business or farms if they were not formally employed. Among the surveyed population, we found that 466 (15%) adults were smokers and no child smokers. The proportion of educated people who smoked was higher in Mirpur than in Savar. The smoking prevalence among those with no education was, however, similar in both areas. Table 1 provides further demographic information about the respondents.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the surveyed population (unweighted; n=3131)

| Characteristics | Mirpur (n=2118) |

Savar (n=1013) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers (n=320) |

Non-smokers (n=1798) |

Smokers (n=146) |

Non-smokers (n=867) |

|||||

| Frequency | Per cent | Frequency | Per cent | Frequency | Per cent | Frequency | Per cent | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 316 | 98.8 | 776 | 43.2 | 135 | 92.5 | 388 | 44.8 |

| Female | 4 | 1.2 | 1022 | 56.8 | 11 | 7.5 | 479 | 55.2 |

| Age group | ||||||||

| Up to 18 years | 0 | 0 | 704 | 39.2 | 0 | 0 | 418 | 48.2 |

| 18+ years | 320 | 100 | 1094 | 60.8 | 146 | 100 | 449 | 51.8 |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Housewife | 4 | 1.2 | 187 | 10.4 | 3 | 2.1 | 103 | 11.8 |

| Small-medium entrepreneur/farmer | 140 | 43.8 | 78 | 4.3 | 77 | 52.7 | 43 | 5.0 |

| Service holder (public and private) | 71 | 22.2 | 121 | 6.7 | 39 | 26.7 | 40 | 4.6 |

| Rickshaw puller/day labourer | 41 | 12.8 | 27 | 1.5 | 23 | 15.7 | 8 | 1.0 |

| Student | 7 | 2.2 | 77 | 4.3 | 2 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Unemployed | 21 | 6.6 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 36 | 11.2 | 1306 | 72.6 | 2 | 1.4 | 670 | 77.3 |

| Education | ||||||||

| No education | 95 | 29.7 | 427 | 23.7 | 49 | 33.6 | 263 | 30.3 |

| Primary level | 51 | 15.9 | 541 | 30.1 | 48 | 32.9 | 371 | 42.8 |

| Up to secondary (SSC) level | 83 | 25.9 | 488 | 27.1 | 39 | 26.7 | 190 | 21.9 |

| SSC+ | 91 | 28.5 | 342 | 19.0 | 10 | 6.8 | 43 | 5.0 |

SSC, Secondary School Certificate.

Smoking prevalence and smoking pattern at home

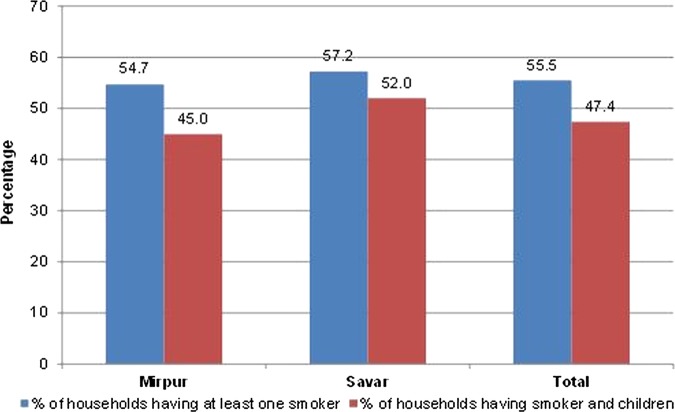

In the study areas, more than half the households (55.5%: 95% CI 50% to 61%) had at least one adult smoker. The percentage of households having one smoker was higher in Savar (57.2%: 95% CI 53% to 61%) than in Mirpur (54.7%: 95% CI 50% to 59%; table 2). The average number of cigarettes/bidi consumed per day was 11.2 (SD 2.5) in Mirpur and 14 (SD 1.5) in Savar.

Table 2.

Smoking prevalence at home

| Indicators | Mirpur (n=472) | Savar (n=250) | Total (n=722) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers (%) of households having at least one smoker | 258 (54.7) (95% CI 50% to 59%) | 143 (57.2) (95% CI 53% to 61%) | 401 (55.5) (95% CI 50% to 61%) |

| Numbers (%) of households having at least one smoker and at least one child | 212 (45.0) (95% CI 39% to 51%) | 130 (52.0) (95% CI 49% to 55%) | 342 (47.4) (95% CI 39% to 55%) |

| Numbers (%) of households where smoking occurred in the presence of children | 131 (27.8) (95% CI 24% to 32%) | 88 (35.0) (95% CI 34% to 36%) | 219 (30.3) (95% CI 24% to 36%) |

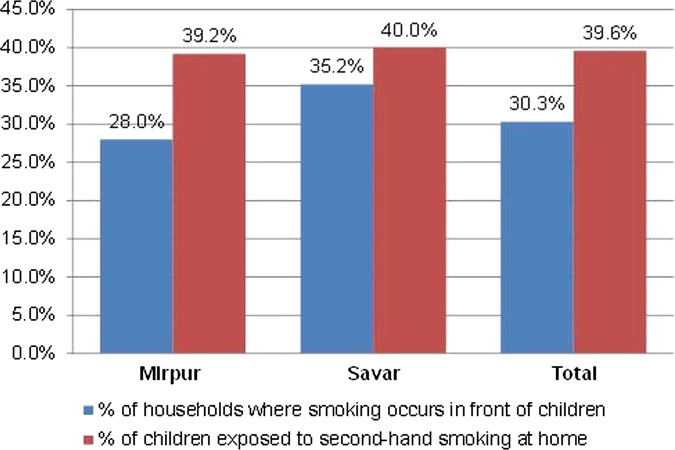

We surveyed 772 households in two areas, and found 342 houses having at least one smoker and a child (table 2 and figure 1). Among them, respondents in 219 households (30.3% of 722) said they smoked in the presence of children. A total of 443 children, who were living in these 219 households, were therefore exposed to second-hand smoking. This represents 39.6% of the children (1122) living in the surveyed households (figure 2). Both the proportion of households where individuals smoked in the presence of children and the proportion of children exposed to SHS was higher in Savar than in Mirpur.

Figure 1.

Smoking pattern at home.

Figure 2.

Children exposed to second-hand smoke (SHS).

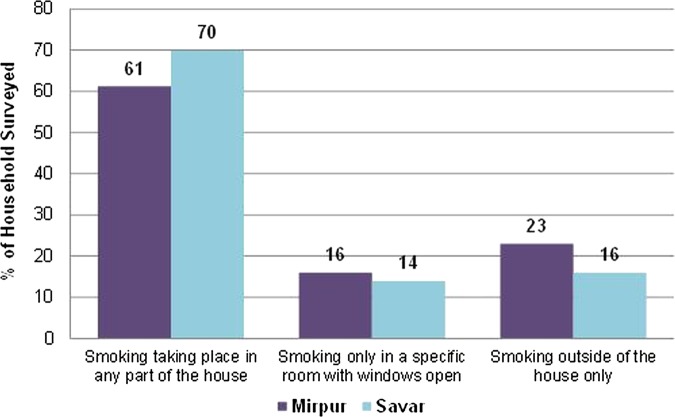

Smoking restrictions at home

We found that unrestricted smoking is a familiar feature in a majority of the households. Among those households where there was at least one smoker, 61% of households in Mirpur (158/258, 95% CI 58% to 64%) and 70% in Savar (100/143, 95% CI 69% to 71%), smokers did not maintain any smoking restrictions at home. Only 23% (60/258, 95% CI 21% to 25%) of households in Mirpur and 16% (23/143, 95% CI 14% to 18%) of households in Savar had complete restrictions on smoking inside the house (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Smoking restrictions at home in the presence of children.

Smoking habits and practices at home

Data from interviews and FGDs revealed that most smokers smoked freely inside the house, and in the presence of children. Only a few respondents smoked outside of the house, most commonly in the balcony or rooftop; but they smoked indoors while watching popular TV shows or in adverse weather conditions. A female schoolteacher stated

My father-in-law is a cricket fan. He usually goes out to the balcony during smoking but he keeps on smoking cigarettes and drinking tea when watching the live cricket game. He also invites other friends to come over to watch the game together. Some of his friends are also smokers; so the house soon becomes very smoky. My two kids love to sit on their grandfather's lap but I never thought that second-hand smoking could cause harm to them. After talking to you I am now very scared.

Some respondents added that smokers abide by smoking restrictions in their workplaces but restrictions were not practised within their own homes. They admitted that workplaces generally have stricter ‘no-smoking’ policies and staff are obliged to obey these or be penalised. However, they added that no such obligations apply at homes. Some female participants also raised the issue of cultural norms of the country: where men enjoy the ‘superior social status’ in the family, while women and children have ‘limited voices’. One respondent said

My husband works as a peon in a bank, and he cannot smoke freely during working hours because smoking is prohibited in the air-conditioned rooms. He is also afraid of punishment if he is caught. So, he smokes a lot at home as if he is compensating for his daily smoking quota. Moreover, there is no worry of losing job (or losing anything) for smoking at home.

Some non-smoking women respondents mentioned their dislike of their husbands, fathers-in-laws or brothers-in-laws smoking in the presence of children. They also mentioned that they disliked the smell of cigarettes/bidi. However, as they were not aware of the harm caused by SHS, they rarely requested smokers to smoke outside the house. One respondent said

My husband always smokes in the front room of the house with his friends in the evening. We usually close all windows in the evening so that mosquitoes cannot enter in the house or for security reasons. Maybe I am avoiding malaria or dengue at the cost of something which is even more dangerous to us [i.e. the health hazard due to SHS.

Knowledge about harmful effects of exposure to SHS on children

Knowledge of people was assessed in terms of their perception regarding health risks of smoking and SHS. During FGDs, a vast majority of respondents admitted that they were aware of the health risks of smoking, especially to children and pregnant women. On the contrary, most believed that SHS has no adverse impact at all. One respondent (male, local leader) stated

Smoking is harmful for my own health but it cannot harm my son if I smoke in front of him. This is because he is not a smoker and he may breathe very small amount of smoke. Anyway, the smoke which actually comes out of my cigarette is very light.

When asked, participants could only identify a few health problems linked to smoking. The most common risks identified were gum problems, asthma, cancer and heart diseases. Furthermore, it emerged during FGDs and in-depth interviews that people held various misconceptions regarding SHS. In response to a question about the harmful effects of SHS, some respondents stated that SHS could only cause asthma or cancer if a non-smoker (or child) stands very close to the smoker over a long time. The other misconceptions held by the respondents were that children would not be affected if they (smokers) smoked during the period when children were not at home. Some respondents also believed that the tobacco smoke vanishes within few minutes and as such could not have any impact on other non-smokers if they were not present at the time of smoking. One respondent (male, shopkeeper) stated

Smoking in front of other persons does not always do harm to them. If a person stands very close to a smoker and if this happens every day for many years, then this might cause asthma. But I know asthma is a hereditary disease and in reality, this [asthma] rarely happens from second-hand smoking. I have never heard of this

Interventions to reduce exposure to SHS and possible challenges

Respondents strongly felt that an appropriate and participatory community awareness programme could bring changes in the behaviour and practice of smokers and could make homes tobacco smoke free. Respondents suggested that leaflets and posters on SHS could be distributed and displayed in places such as health centres, schools, shopping malls, and bus and train stations. Community meetings, seminars, workshops, sports and cultural programmes could be arranged to create awareness in the community on issues related to SHS.

During the FGDs, a number of male smokers spontaneously expressed their intention to change their smoking behaviour and initiate smoking restrictions at home. One respondent (male, local leader) said

If I had known that I have been causing so much harm to my children by exposing them to second-hand smoking, I would have never smoked in front of them. I promise that as a ‘good’ father I will never smoke in front of my children. I also believe that all fathers would do the same if they were given proper knowledge and information about harmful effects of second-hand smoking

When asked about the role of the community, respondents felt that different civil society and institution members such as teachers and students, lawyers, religious leaders, journalists, doctors, health workers, along with children and youth could be engaged in influencing smoking member(s) of the family/community to refrain from smoking in the presence of any other non-smoking persons.

The interviewees and FGD participants identified several barriers in applying smoking restrictions at home. The major constraint was the knowledge gap and lack of awareness among smokers and other family members about the harmful effects of SHS. This lack of awareness was the biggest impediment in taking any initiative toward protecting children and other non-smoking adults from SHS.

One respondent (female, housewife) stated

My father-in-law generally smokes in the dining room after meals, and in most cases in front of my son aged 6 years. My son often starts coughing due to the tobacco smoke. However, due to my limited knowledge on the adverse effects of second-hand smoking, I am not sure how to tell my father-in-law to stop smoking in front of my son and how to convince him to quit smoking altogether. Moreover, he is an elderly person and we must show respect to him

A number of female respondents also argued that the major challenges in implementing smoking restrictions at home are male attitudes and behaviours. They suggested that women and children need to be empowered through training and awareness-raising activities to implement smoking restrictions at home. The wife and/or children within the family could be in a strong position to persuade their husband/father in changing their smoking practices. One schoolteacher (male) recalled that

My father used to smoke. He did not listen to my grandmother or my mother to change his smoking habits. But when my sister requested my father to reduce smoking, he was compelled to do so as he loved my sister very much.

Discussion

Smoking inside the home was found to be common practice, with more than half of households having at least one smoker. A majority of smokers did not restrict their smoking at home. Moreover, the practice of smoking in the presence of children was widespread, putting children at risk of SHS-related harm. Our findings show that almost 40% of children were exposed to SHS, the proportion of such exposure being higher in rural than in urban areas. While there was some awareness of the adverse effects of first-hand smoking, there was a considerable knowledge gap regarding the harmful effects of SHS. However, there was a strong belief that such knowledge and awareness could enable non-smoking members to initiate dialogue about smoking restrictions at the household level. It was also evident that family members were motivated to adopt smoking restrictions at home.

In developing countries, there is limited evidence available on the exposure to SHS particularly among children, except for Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data.17 18 Moreover, available data from various countries cannot be truly compared given the varying age parameters for defining a child. GYTS reported the exposure rates in Bangladesh (34.7%), China (56.1%), Indonesia (66.8%) and India (48.2%) among children aged 13–15 years,17 but the rate was much higher in Bangladesh (67%) among children younger than 13 years.14 Moreover, a survey in rural Pakistan revealed that smoking in the presence of children in households with at least one smoker was 91%.19 Öberg et al3 also estimated that 40% of children younger than 14 years of age worldwide were exposed to SHS.

We found variations in smoking practices between the two study areas. The proportion of households having at least one smoker, the average number of cigarettes/bidi consumed per day, the proportion of households where unrestricted smoking took place at home, and the proportion of children exposed to SHS were higher in Savar than in Mirpur. This can partly be explained by the lower literacy rate in Savar. Smoking prevalence in Bangladesh is higher among people with lower levels of educational achievements.10 There is also evidence to suggest that homes tend to have fewer restrictions on smoking when heads of households did not receive education beyond school.20

This study further suggests that there is a need to develop innovative approaches to change smoking habits and practices, both in terms of limiting smoking inside the house and abstaining from smoking in the presence of children. Approaches that convey simple, tailored smoke-free messages by using existing social and educational structures have been suggested.21––23 There remains ample scope to involve schools, health centres, civil society members, NGOs and government to implement such approaches, thereby reducing exposure of children to SHS.21 Evidence also suggests that non-smoking parents with higher education are more supportive of tobacco preventative initiatives than those who smoke and/or have lower educational achievements.24

Our study identified that complex family traditions and cultural norms limit the scope of applying any type of smoking restrictions at home.25 Male dominance, low-socioeconomic status of women and absence of children's participation in family affairs are pervasive in rural and urban areas. In addition, senior family members and visiting family guests generally enjoy a perceived indemnity against any unacceptable practice such as smoking inside the house.18 26

The primary limitation of the study is that the survey data were collected from an adult member present at the time of survey, which could potentially introduce informant bias in conveying an idealistic image particularly if the respondent was a smoker: during interviews and FGDs, respondents may have been inclined to say what they perceived as socially or culturally correct answers. Findings were also not validated using any cotinine measurements or environmental exposure assessment. Although we wished to determine the extent of children exposed to SHS, there was no attempt to establish the association of exposure to SHS with any existing health conditions among children. There was no intention to demonstrate that the study sample is representative of the national population; however, the geographical and demographic characteristics of the selected study areas correspond with other typical urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. It is expected that there might be some geographical variations, the true extent of which will remain unknown until a more representative survey is conducted.

Conclusion

We found that many children in Bangladesh are exposed to SHS at home, posing a serious public health concern. There is a need for evidence-based interventions to protect them from this threat. However, a number of barriers including social and family norms need to be recognised while initiating such restrictions at home. Further research is needed to look at the feasibility of interventions in changing adult smoking behaviour and restrictions at home in Bangladesh.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants. They also thank colleagues at the National Health Service (NHS), Leeds; Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, University of Leeds, UK; and Society for Empowerment, Education and Development (SEED) for their support, contributions and suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: ANZU conceived and designed the study, led the data collection and analysis, and involved in preparation of the manuscript. RH and HA participated in the data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. SN participated in data collection and analysis. SA coordinated the study implementation and data collection. IC and HT advised on the design and methodology of the study and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. JNN participated in the analysis and preparation of the manuscript. KS participated in the design of the study, advised on data collection and analysis and participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the NHS, Leeds, UK.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Leeds, UK; University of York, UK; and Bangladesh Medical and Research Council (BMRC), Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Leung CC, et al. Passive smoking and tuberculosis. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:287–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treyster Z, Gitterman B. Second hand smoke exposure in children: environmental factors, physiological effects, and interventions within pediatrics. Rev Environ Health 2011;26:187–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011;377:139–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriz P, Bobak M, Kriz B, et al. Parental smoking, socioeconomic factors, and risk of invasive meningococcal disease in children: a population based case-control study. Arch Dis Child 2000;83: 117–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofhuis W, de Jongste JC, Merkus PJ. Adverse health effects of prenatal and postnatal tobacco smoke exposure on children. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:1086–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Bank (The), Tobacco Control—at a glance, 2011

- 7.Farkas AJ, Gilpin EA, White MM, et al. Association between household and workplace smoking restrictions and adolescent smoking. JAMA 2000;284:717–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw A, Ritchie D, Semple S, et al. Reducing children's exposure to second hand smoke in the home: a literature review. A report by ASH Scotland, 2012

- 9.Öberg M, Woodward A, Jaakkola MS, et al. Global estimate of the burden of disease from second-hand smoke. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Bangladesh Report 2009.

- 11.Best CM, Sun K, de Pee S, et al. Parental tobacco use is associated with increased risk of child malnutrition in Bangladesh. Nutrition 2007;23:731–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation (WHO) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic—the MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) National strategic plan of action for tobacco control 2007–2010. Dhaka: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Bangladesh, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Women and Children Affairs (2010) Bangladesh Child Policy, 2010

- 15.Öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Prüss-Ostün A, et al. Second-hand smoke—assessing the burden of disease at national and local levels. Environmental Burden of Disease Series 18. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.ASH Research Report 2011. Secondhand Smoke, 2011. http://www.ash.org.uk

- 17.WHO World Health Organisation (WHO) Report on Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) and Global School Personnel Survey (GSPS) 2007 in Bangladesh. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, New Delhi, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdullah AS, Hitchman SC, Driezen P, et al. Socioeconomic differences in exposure to tobacco smoke pollution (TSP) in Bangladesh households with children: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Bangladesh Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:842–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqi K, Sarmad R, Usmani RA, et al. Smoke-free homes: an intervention to reduce second-hand smoke exposure in households. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010;14:1336–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alwan N, Siddiqi K, Thomson H, et al. Children's exposure to second-hand smoke in the home: a household survey in the North of England. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thu NL. Creating smoke free homes: developing effective messages and strategies for women to persuade husbands to stop smoking inside the house. Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) and Ministry of Health, Vietnam, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauld L, Brandling J, Templeton L. Facilitators and barriers to the delivery of school-based interventions to prevent the uptake of smoking among children: a systematic review of qualitative research. UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw A, Amos A, Semple S, et al. Reducing children's exposure to second hand smoke in the home—a mapping survey of smoke-free home initiatives in Scotland and England; A report by ASH Scotland, 2011

- 24.Carlsson N, Johansson NK, Hermansson G, et al. Parents’ attitudes to smoking and passive smoking and their experience of the tobacco preventive work in child health care. J Child Health Care 2011;15:272–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control 2000;9:47–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Donate AP, Hovell MF, Meltzer SB, et al. The association between residential tobacco smoking bans, smoke exposure and pulmonary function: a survey of Latino children with asthma. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol 2003;16:305–17 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.