Abstract

Objective

To study the usefulness of combined risk stratification of coronary CT angiography (CTA) and myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) in patients with previous coronary-artery-bypass grafting (CABG).

Design

A retrospective, observational, single centre study.

Setting and patients

204 patients (84.3% men, mean age 68.7±7.6) undergoing CTA and MPI.

Main outcome measures

CTA defined unprotected coronary territories (UCT; 0, 1, 2 or 3) by evaluating the number of significant stenoses which were defined as the left main trunk ≥50% diameter stenosis, other native vessel stenosis ≥70% or graft stenosis ≥70%. Using a cut-off value with receiver-operating characteristics analysis, all patients were divided into four groups: group A (UCT=0, summed stress score (SSS)<4), group B (UCT≥1, SSS<4), group C (UCT=0, SSS≥4) and group D (UCT≥1, SSS≥4).

Results

Cardiac events, as a composite end point including cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularisation and heart-failure hospitalisation, were observed in 27 patients for a median follow-up of 27.5 months. The annual event rates were 1.1%, 2%, 5.7% and 12.9% of patients in groups A, B, C and D, respectively (log rank p value <0.0001). Adding UCT or SSS to a model with significant clinical factors including left ventricular ejection fraction, time since CABG and Euro SCORE II improved the prediction of events, while adding UCT and SSS to the model improved it greatly with increasing C-index, net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement.

Conclusions

The combination of anatomical and functional evaluations non-invasively enhances the predictive accuracy of cardiac events in patients with CABG.

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A limited number of patients in a single centre were enrolled and observed retrospectively.

In a large number of prospective studies, the usefulness and cost-effectiveness of combined evaluation will be studied further.

We did not perform invasive coronary angiography in all studied patients. (The diagnosis of unprotected coronary territory based on CT angiography may contain some false-positives and/or false-negatives.)

Introduction

Coronary CT angiography (CTA) is a useful tool not only for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD),1–3 but also for the risk stratification of patients with CAD.4 5 Some studies using CTA have shown good diagnostic performance for the detection of significant stenosis in grafts, with accuracy improved by the newer generation of CT scanners.6–9 Recently, Chow et al10 and Small et al11 demonstrated that CTA was of prognostic value in patients with previous coronary-artery-bypass grafting (CABG). On the other hand, CTA has some limitations in the evaluation of distal run-offs, metal clip artefacts and native coronary segments of non-grafted vessels, particularly due to the high prevalence of severe calcification in patients with previous CABG.6 8

Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) has also been useful for the risk stratification of patients with previous CABG.12–14 MPI is regarded as the gold standard for the risk stratification of such patients,15 despite some limitations. Patients after CABG have a high prevalence of perfusion defects because of the prior myocardial infarction or ischaemic areas resulting from a coronary side branch occlusion, and so there is a low positive predictive value for prognostic evaluation.

In previous studies, Schuijf et al16 showed that MPI and CTA provided different and complementary information on patients with suspected CAD. Werkhoven et al17 concluded that combined anatomical and functional assessment might allow improved risk stratification. The purpose of the present study was to assess the prognosis of patients with CABG by CTA and MPI, as well as to determine the efficacy of such combined anatomical and functional assessment.

Methods

We studied 211 patients with a history of CABG. From January 2006 to October 2011, they underwent CTA and MPI within 3 months of each other, and their clinical end points were followed. Exclusion criteria were: (1) complicating congenital heart disease; (2) after valve surgery or left ventricular aneurysm resection; (3) known allergy to iodinated contrast agents; (4) severe renal insufficiency not requiring haemodialysis (estimated glomerular filtration rate<30 mL/min/1.73 m2). To determine the preoperative risk assessment of these patients, we used a logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation risk model (EuroSCORE II).18 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the ethics committee of Fujita Health University.

Coronary CTA

In the first 27 patients, a 64-slice CT (Aquilion 64, Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) was used with a collimation of 64×0.5 mm, rotation speed of 350, 375, 400 ms and retrospective gating ECG. For the contrast-enhanced scan, a total amount of 80–90 mL of contrast medium with an injection flow rate of 4 mL/s was injected, followed by a 40 mL saline bolus chase. Volumetric data were reconstructed with segmented reconstruction.9 In the remaining 184 patients, a 320-slice CT (Aquilion One Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) was used with a collimation of 320×0.5 mm, rotation speed of 350, 375, 400 ms and prospective triggering ECG. A bolus of 1.1 mL/kg contrast medium was injected over 18 s, followed by a 20 mL saline bolus chase. Volumetric data were reconstructed with half or segmented reconstruction.19 All scans were performed during a single breath-hold. Isosorbide dinitrate spray 1.25 mg was provided immediately before CTA. The effective radiation dose was 12.7±9.1 mSv (9.8±3.7 mSv in a 320-slice CT and 32.6±10.4 mSv in a 64-slice CT). After acquisition of the reconstructed volumetric data, images were transferred to a workstation (ZIOSTATION System 1000, Amin/ZIO, Tokyo, Japan). On the CT images, coronary arteries were divided into 15 segments based on the recommendations of the American Heart Association.20 All native coronary arteries and bypass grafts were evaluated by two experienced observers (SM and HI) unaware of the clinical history and MPI findings of the patients. Atherosclerotic lesions and stenoses were classified visually as mild (<50% luminal diameter), moderate (50–69%) or severe (≥70%). Significant stenoses were defined as left main trunk (LMT) ≥50% diameter stenosis, other native vessel stenosis ≥70% or graft stenosis ≥70%. Native coronary segments (including stented segments) and grafts, which were not assessable because of severe calcification and motion artefacts, were regarded as severe stenoses. Patients were categorised according to the number (0, 1, 2 or 3) of unprotected coronary territories (UCT).10 Each patient had three coronary territories, corresponding to each major epicardial artery (left anterior descending artery, circumflex artery or artery supplying the posterior descending artery (right coronary artery or circumflex artery)) and their corresponding branches (diagonal and marginal arteries). A coronary territory was deemed unprotected if: (1) an ungrafted native coronary artery had a significant stenosis; (2) a significant stenosis in the native artery was distal to the graft insertion or (3) a native artery and its graft both had significant stenoses.

Stress-rest MPI

In all patients, stress-rest MPI using thallium (Tl)-201 was performed with adenosine stress.21 Early single photon emission tomography (SPECT) was performed 10 min after the adenosine stress test; late SPECT was performed 4 h thereafter. SPECT images were acquired using a dual-headed SPECT ɣ camera (ADAC VERTEX-plus; EPIC, USA). Tomographic reconstruction was performed using a standard filtered back-projection technique with a ramp filter to produce a transaxial tomogram. No scatter or attenuation correction was applied. From these transaxial tomograms, the long axis of the left ventricle was identified, and oblique-angled tomograms were generated (ie, vertical long-axis, short-axis and horizontal long-axis tomograms).22 The Tl-201 uptake was graded subjectively in three orthogonal planes (short axis, horizontal long axis, vertical long axis) divided into 17 segments on a five-point scale (4=absent uptake; 3=severely, 2=moderately, 1=mildly decreased uptake; 0=normal uptake, respectively) on the post-stress and delayed images displayed side by side by the consensus of two experienced observers (MS and HK) unaware of the clinical history and CTA findings of the patients.19 The segmental perfusion scores during stress and rest were added together to calculate the summed stress score (SSS), the summed rest score (SRS) and the summed difference score (SDS).

Patient follow-up

Patient follow-up data were gathered by observers blinded to the baseline CTA and MPI results using clinical visits or standardised telephone interviews. Cardiac events (cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularisation and admission to a hospital due to heart failure) were regarded as clinical end points. Deaths were considered as cardiac when the primary cause of death was related to myocardial ischaemia/infarction, heart failure or arrhythmia, and when a non-cardiac cause of death could not be identified. Non-fatal myocardial infarction was defined as myocardial ischaemia resulting in abnormal cardiac biomarkers (>99th centile of the upper normal limits). Unstable angina was defined as acute chest pain with or without the presence of ECG abnormalities and negative cardiac enzyme levels.23 24 Patients undergoing elective revascularisation within 3 months after CTA or MPI (early elective revascularisation) were excluded after enrolment.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean±SD for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The mean values for the two groups were compared with χ2 tests for categorical and Wilcoxon sum rank tests for continuous variables. All analyses were performed with JMP V.10, (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and a p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

The prognosis of patients with CABG was assessed in univariate and multivariate models based on UCT, SSS and their combination. Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was performed to determine cut-off values of UCT and SSS for cardiac events. Risk adjusted analyses were performed with Cox proportional hazard models to determine the independent prognostic value of UCT, SSS and their combination by controlling for other predictors. Cumulative event rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test.

The increased discriminative value after the addition of UCT and/or SSS to the established clinical risk factors was estimated using the C-index for ROC curve, net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). The C-index is defined as the area under an ROC curve between individual predicted probabilities and incidence of events, and is compared in a baseline model consisting of established clinical risk factors with p<0.05 by univariate Cox analysis, and in an enriched model with UCT and/or SSS.25 NRI indicates relatively how many patients show a decrease in their predicted probabilities for events, while IDI represents the average decrease in predicted probabilities for events after adding UCT and/or SSS, respectively, into the baseline model.26

Results

Clinical characteristics

In total, 204 patients (84.3% men, mean age 68.7±7.6 years) were enrolled after excluding 7 patients: 4 undergoing early elective revascularisation within 3 months after imaging examination and three lost to follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 30.3±17.6 months (median; 27.5 months). Four patients who underwent early revascularisation were excluded because we could not study their natural histories after examination. In table 1, the baseline characteristics are listed in detail. At follow-up, cardiac events were observed in 27 patients (13.2%) with an annualised event rate of 5.2% (3 patients with cardiac death, 9 patients with non-fatal infarction, 3 patients with unstable angina requiring revascularisation and 12 patients with heart failure). In the univariate Cox analysis, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) determined by cardiac ultrasound (HR 0.936; 95% CI 0.905 to 0.968; p=0.0002), time since CABG (HR 1.01; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.02; p=0.0008) and EuroSCORE II (HR 1.29; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.57; p=0.038) were significant predictors of cardiac events.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All (n=204) | Cardiac events (n=27) | No events (n=177) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.7±7.6 | 70.0±7.7 | 68.5±7.6 | 0.46 |

| Gender (male) | 172 (84.3%) | 21 (77.8%) | 151 (85.3%) | 0.527 |

| Diabetes | 106 (52.0%) | 17 (63.0%) | 89 (50.3%) | 0.234 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 116 (56.9%) | 18 (66.7%) | 98 (55.4%) | 0.214 |

| Hypertension | 172 (84.3%) | 24 (88.9%) | 148 (83.6%) | 0.673 |

| Haemodialysis | 9 (4.4%) | 2 (7.4%) | 7 (4.0%) | 0.229 |

| Current smoker | 39 (19.1%) | 5 (18.5%) | 34 (19.2%) | 0.905 |

| LVEF (%) | 52.1±9.9 | 44.9±11.5 | 53.2±9.3 | 0.0002 |

| Time since CABG (months) | 25.3±51.2 | 55.8±66.7 | 20.7±47.0 | 0.0008 |

| Prior MI | 34 (16.7%) | 8 (29.6%) | 26 (14.7%) | 0.08 |

| Post PCI | 23 (11.3%) | 5 (18.5%) | 18 (10.2%) | 0.319 |

| Prior HF | 17 (8.3%) | 3 (11.1%) | 14 (7.9%) | 0.539 |

| Using ITA | 191 (93.6%) | 23 (85.2%) | 168 (94.9%) | 0.089 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.90±1.32 | 2.43±1.69 | 1.81±1.24 | 0.038 |

CABG, coronary aorta bypass graft; HF, heart failure; ITA, internal thoracic artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction by ultrasonic cardiography; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

CTA, MPI findings and analysis with the combination of UCT and SSS

The mean UCT was 0.51±0.72, and percentages of uninterpretable segments on CTA were 0.4%, 7.37% and 3.61% in grafts, LMT and other coronary artery segments, respectively. The mean SSS, SRS and SDS were 7.03±8.65, 5.21±7.70 and 1.82±3.23, respectively. The mean percentage of fixed defects was 10.3%.

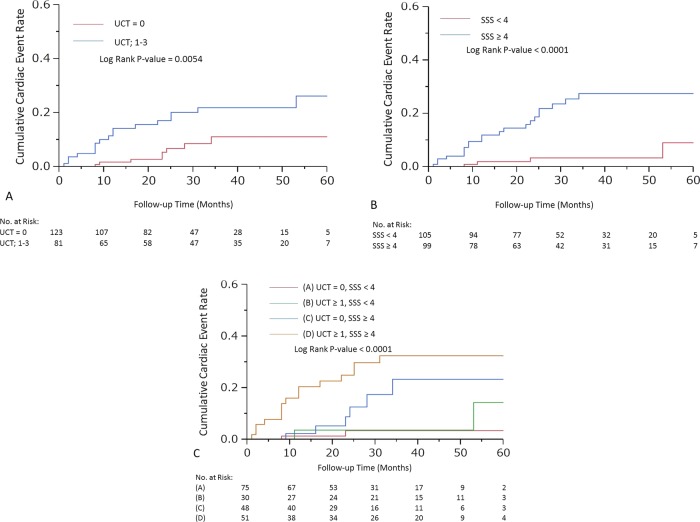

UCT and SSS were significant predictors for cardiac events (HR 2.52; 95% CI 1.59 to 3.96; p=0.0001 and HR 1.08; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.12; p<0.0001, respectively). To maximise the predictive power of UCT and SSS, cut-off levels were determined as 1 for UCT (area under curve (AUC)=0.71) and 4 for SSS (AUC=0.76), respectively. The cumulative incidence rates for cardiac events are demonstrated in figure 1A,B (log rank p value =0.0054 and <0.0001, respectively). After adjustment for LVEF, time since CABG and EuroSCORE II, patients with UCT≥1 had a 2.34-fold higher risk of cardiac events (95% CI 1.01 to 5.89, p=0.0465). Similarly, patients with SSS≥4 had a 3.36-fold higher risk of cardiac events (95% CI 1.18 to 12.12, p=0.0217; table 2).

Figure 1.

Cardiac event curves according to (A) unprotected coronary territory (UCT), (B) summed stress score (SSS), (C) each group.

Table 2.

CTA, MPI findings: univariable and multivariate analysis for cardiac events

| Cardiac events (n=27) | No events (n=177) | Annual event rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCT=0 | 8 (6.5%) | 115 (93.5%) | 2.82 | 1 | 1 | ||

| UCT≥1 | 19 (23.5%) | 62 (76.5%) | 8.27 | 3.07 (1.38 to 7.49) | 0.0054 | 2.34* (1.01 to 5.89) | 0.0465 |

| SSS<4 | 4 (3.8%) | 101 (96.2%) | 1.44 | 1 | 1 | ||

| SSS≥4 | 23 (23.2%) | 76 76.8%) | 9.67 | 6.73 (2.59 to 22.96) | <0.0001 | 3.36† (1.18 to 12.12) | 0.0217 |

*HR was adjusted for LVEF, time since CABG, EuroSCORE II and SSS.

†HR was adjusted for LVEF, time since CABG, EuroSCORE II and UCT. Eight events in patients with UCT=0 included three non-fatal MI and five HF, 19 events in UCT≥1 included three cardiac deaths, six non-fatal MIs, three late revascularisations and seven HFs. Four events in patients with SSS<4 included three non-fatal MIs and one late revascularisation, 23 events in SSS≥4 included three cardiac deaths, six non-fatal MIs, two late revascularisations and 12 HFs.

CABG, coronary-artery-bypass grafting; CTA, CT angiography; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation risk model; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; SSS, summed stress score; UCT, unprotected coronary territory.

On the basis of the CTA and MPI findings, we divided all patients into four groups: group A (UCT=0, SSS <4), group B (UCT≥1, SSS<4), group C (UCT=0, SSS≥4) and group D (UCT≥1, SSS≥4). The annual event rates of cardiac events were 1.1%, 2%, 5.7% and 12.9% of patients in groups A, B, C and D, respectively. Cardiac event curves are demonstrated in figure 1C (log rank p value <0.0001). After adjustment for LVEF, time since CABG and EuroSCORE II, patients with UCT≥1 and SSS≥4 had a 6.84-fold (95% CI 1.83 to 44.50, p=0.0026) higher risk for cardiac events compared with those with UCT=0 and SSS<4 (table 3).

Table 3.

Combination of UCT and SSS (univariable and multivariate analysis for cardiac events)

| Group | UCT | SSS | Number of patients | Number of patients with cardiac events (%) | Annual event rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | <4 | 75 | 2 (2.7) | 1.1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| B | ≥1 | <4 | 30 | 2 (6.7) | 2.0 | 1.93 (0.23 to 16.16) | 0.515 | 1.76 (0.21 to 15.11) | 0.579 |

| C | 0 | ≥4 | 48 | 6 (13.0) | 5.7 | 5.15 (1.19 to 35.17) | 0.0279 | 2.73 (0.55 to 19.93) | 0.225 |

| D | ≥1 | ≥4 | 51 | 17 (33.0) | 12.9 | 11.9 (3.40 to 75.19) | <0.0001 | 6.84 (1.83 to 44.5) | 0.0026 |

*HR was adjusted for LVEF, time since CABG and EuroSCORE II.

CABG, coronary-artery-bypass grafting; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation risk model; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SSS, summed stress score; UCT, unprotected coronary territory.

Discrimination of each predicting model for cardiac events

The addition of UCT alone, SSS alone and both UCT and SSS to a baseline model with clinical risk factors consisting of LVEF, time since CABG and EuroSCORE II significantly improved both the NRI and IDI. However, the C-index was significantly greater only in the model with both UCT and SSS compared with the baseline model (0.834 vs 0.768, p=0.045). In addition, NRI and IDI increased significantly in the model containing both UCT and SSS even if compared with the model containing UCT alone or SSS alone (table 4).

Table 4.

Discrimination of each predicting model for cardiac events

| Discrimination |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors and imaging findings | C index (95% CI) | p Value | NRI | p Value | IDI | p Value |

| Clinical risk factors† | 0.768 (0.655 to 0.880) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Clinical risk factors† plus UCT | 0.811 (0.718 to 0.905) | 0.1049 | 0.707 | 0.0003* | 0.0369 | 0.0235 |

| Clinical risk factors† plus SSS | 0.807 (0.701 to 0.912) | 0.1156 | 0.731 | 0.0002* | 0.0421 | 0.0005 |

| Clinical risk factors† plus UCT and SSS | 0.834 (0.742 to 0.927) | 0.0454* | 0.649 | 0.0008* | 0.0701 | 0.0006 |

| Clinical risk factors† plus UCT | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Clinical risk factors† plus UCT and SSS | 0.1989 | 0.707 | 0.0003* | 0.0281 | 0.039 | |

| Clinical risk factors† plus SSS | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Clinical risk factors† plus UCT and SSS | 0.1486 | 0.645 | 0.0009* | 0.0333 | 0.0009 | |

*p Value<0.05.

†Clinical risk factors comprise LVEF, time since CABG, and EuroSCORE II.

CABG, coronary-artery-bypass grafting; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation risk model; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NRI, net reclassification improvement; SSS, summed stress score; UCT, unprotected coronary territory.

Discussion

We focused on the prognosis of patients with CABG assessed by CTA and MPI, and the usefulness of this combination. The patients without unprotected territories on CTA and without perfusion defects on MPI have a good prognosis. The prognosis of patients with abnormal CTA (UCT≥1) and MPI (SSS≥4) is significantly poorer than that of patients with normal CTA and MPI. Each examination has incremental prognostic value, and the combination of anatomical and functional evaluation facilitates non-invasive assessment of the prognosis of patients with CABG. This improvement was indicated to be statistically significant by the increase in the NRI and IDI.

Several reports have shown the utility of MPI with assessment of the prognosis in patients with CABG,12–14 but there are some limitations.

First, many patients with CABG have some abnormal findings on MPI, because of a history of prior myocardial infarctions, and others have ischaemic territories with side branch occlusions even if the major coronary trees are protected. Actually, in the present study, 48.5% of the enrolled patients had an abnormal MPI finding (SSS≥4). To identify the patients with a poor prognosis strictly among those with MPI abnormalities, the evaluation of UCT on CTA was useful. The event rates were 33.3% in the abnormal patients with CTA (group D), in contrast to 12.5% in the normal patients with CTA (group C).

Importantly, MPI does not clarify the anatomy of grafts or native coronary arteries, even when high-risk patients are identified. On the other hand, CTA provides information on grafts and unprotected native coronary arteries non-invasively, and in this way contributes to devising the most appropriate therapeutic strategy.

Several studies have also demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of CTA in patients with CABG,6–9 and two recent studies reported the prognostic value of CTA in patients with CABG.10 11 They concluded that assessment with CTA is of prognostic value in patients with CABG, despite some limitations.

First, some difficulties remain regarding the diagnostic accuracy.7–9 Indeed, the diagnostic accuracy of graft segments is good, but patients with CABG have a high prevalence of severe calcifications and stented segments in the native coronary arteries, leading to some overestimation of stenosis of the distal run-off segments of the protected coronary arteries and unprotected native coronary arteries including stented segments. Actually, in our study, unassessable native coronary or graft segments were regarded as severe stenosis, quite likely resulting in some overestimation of the number of UCT. In other words, some CTA findings in group B patients (abnormal CTA and normal MPI) may be false-positives. In a prior study, Chow et al10 excluded cases with >5 unassessable segments. Actually, it is useful to add MPI in the assessment of patients with poor CTA images.

Second, patients with normal CTA may experience any kind of cardiac event. Some patients with major branches protected have an ischaemic or infarcted area due to a prior myocardial infarction or a side branch occlusion, and so the at-risk area might cause fatal arrhythmia and heart failure in them even if the risk of ungrafted coronary events or graft failure is very low. The present study demonstrates that the prognosis of patients with normal CTA and abnormal MPI (group C) is poorer (event-free rate; 87.5%) than that of those with normal CTA and MPI (group A: 97.3).

Finally, prior CTA studies lacked some necessary data.10 11 Small et al11 and Chow et al10 did not obtain data of the time since CABG or the variety of graft types.10 In prior prognostic studies of MPI or CAG, time since CABG and the variety of grafts were identified as important predictors.12–14 When the prognosis of patients with CABG is discussed, information on the time since CABG and the variety of grafts is indispensable.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, a limited number of patients in a single centre were enrolled and observed retrospectively. Additionally, a small number of hard events including cardiac death and non-fatal myocardial infarction was observed during follow-up. Second, we did not perform invasive coronary angiography in all studied patients. The diagnosis of UCT based on CTA may contain some false-positives and/or false-negatives. Last, owing to the lack of data regarding the medical therapy when cardiac events occurred, we could not discuss the appropriateness of medical therapy which may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the combination of MPI and CTA is useful for the risk stratification of patients with previous CABG. The advantages of each imaging examination complement the limitations of the other. The combination of anatomical and functional evaluations enhances the assessment of the prognosis of patients with CABG non-invasively.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HK and MS evaluated myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI). SM and HI evaluated CT imaging. KT and JI performed the MPI examination. HH and HA performed the CT examination. HT and SH gave HK some advice about statistics. YT and MA are CABG operators and attending doctors for most patients. TM and YO conducted this study.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the ethics committee of Fujita Health University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2324–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, van Velzen JE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 320-row multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography in the non-invasive evaluation of significant coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1908–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motoyama S, Anno H, Sarai M, et al. Noninvasive coronary angiography with a prototype 256-row area detector computed tomography system: comparison with conventional invasive coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:773–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulten EA, Carbonaro S, Petrillo SP, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac computed tomography angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1237–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow BJ, Wells GA, Chen L, et al. Prognostic value of 64-slice cardiac computed tomography severity of coronary artery disease, coronary atherosclerosis, and left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1017–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malagutti P, Nieman K, Meijboom WB, et al. Use of 64-slice CT in symptomatic patients after coronary bypass surgery: evaluation of grafts and coronary arteries. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1879–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Graaf FR, van Velzen JE, Witkowska AJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of 320-slice multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur Radiol 2011;21:2285–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weustink AC, Nieman K, Pugliese F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography angiography in patients after bypass grafting: comparison with invasive coronary angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:816–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tochii M, Takagi Y, Anno H, et al. Accuracy of 64-slice multidetector computed tomography for diseased coronary artery graft detection. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1906–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow BJ, Ahmed O, Small G, et al. Prognostic value of CT angiography in coronary bypass patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:496–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Small GR, Yam Y, Chen L, et al. Prognostic assessment of coronary artery bypass patients with 64-slice computed tomography angiography: anatomical information is incremental to clinical risk prediction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2389–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller TD, Christian TF, Hodge DO, et al. Prognostic value of exercise thallium-201 imaging performed within 2 years of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:848–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmas W, Bingham S, Diamond GA, et al. Incremental prognostic value of exercise thallium-201 myocardial single-photon emission computed tomography late after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:403–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauer MS, Lytle B, Pashkow F, et al. Prediction of death and myocardial infarction by screening with exercise-thallium testing after coronary-artery-bypass grafting. Lancet 1998;351:615–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klocke FJ, Baird MG, Lorell BH, et al. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging). American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Society for Nuclear Cardiology. Circulation 2003;108:1404–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuijf JD, Wijns W, Jukema JW, et al. Relationship between noninvasive coronary angiography with multi-slice computed tomography and myocardial perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:2508–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, et al. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography and gated single-photon emission computed tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:623–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:734–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagi Y, Akita K, Kondo H, et al. Non-invasive evaluation of internal thoracic artery anastomosed to the left anterior descending artery with 320-detector row computed tomography and adenosine thallium-201 myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;18:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation 1975;51:5–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura S, Mahmarian JJ, Boyce TM, et al. Quantitative thallium-201 single-photon emission computed tomography during maximal pharmacologic coronary vasodilation with adenosine for assessing coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:736–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial Segmentation and Registration for Cardiac Imaging. Circulation 2002;105:539–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapezzi C, Biagini E, Branzi A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2008;29:277–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Part 10: acute coronary syndromes: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S787–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, D'Agostino RB, Jr,et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.