Abstract

Esophageal tuberculosis is rare, constituting about 0.3% of gastrointestinal tuberculosis. It presents commonly with dysphagia, cough, chest pain in addition to fever and weight loss. Complications may include hemorrhage from the lesion, development of arterioesophageal fistula, esophagocutaneous fistula or tracheoesophageal fistula. There are very few reports of esophageal tuberculosis presenting with hematemesis due to ulceration. We report a patient with hematemesis that was due to the erosion of tuberculous subcarinal lymph nodes into the esophagus. A 15-year-old boy presented with hemetemesis as his only complaint. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed an eccentric ulcerative lesion involving 50% of circumference of the esophagus. Biopsy showed caseating epitheloid granulomas with lymphocytic infiltrates suggestive of tuberculosis. Computerised tomography of the thorax revealed thickening of the mid-esophagus with enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in the subcarinal region compressing the esophagus along with moderate right sided pleural effusion. Patient was treated with anti-tuberculosis therapy (Rifampicin, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol) for 6 mo. Repeat EGD showed scarring and mucosal tags with complete resolution of the esophageal ulcer.

Keywords: Esophageal tuberculosis, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, Hematemesis

Core tip: Esophageal tuberculosis is very rare, constituting about 0.3% of gastrointestinal tuberculosis cases. Esophageal tuberculosis presents commonly with dysphagia, cough, chest pain in addition to fever and weight loss. Complications may include hemorrhage from the lesion, development of arterioesophageal fistula, esophagocutaneous fistula or tracheoesophageal fistula. There are very few case reports of esophageal tuberculosis presenting with hematemesis due to esophageal ulceration. We report a patient with hematemesis that was later attributed to the erosion of tuberculous subcarinal lymph nodes into the esophagus.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal tuberculosis is rare, constituting about 0.3% of gastrointestinal tuberculosis cases[1]. Usual presentation is due to dysphagia, retrosternal pain, fever, cough and weight loss. Complications may include hemorrhage from the lesion, development of arterioesophageal fistula, esophagocutaneous fistula or tracheoesophageal fistula[2] and intramural pseudo-diverticulum[3]. There are very few case reports of esophageal tuberculosis presenting with hematemesis due to esophageal ulceration[2,4,5]. We report a patient with hematemesis that was due to the erosion of tuberculous subcarinal lymph nodes into the esophagus.

CASE REPORT

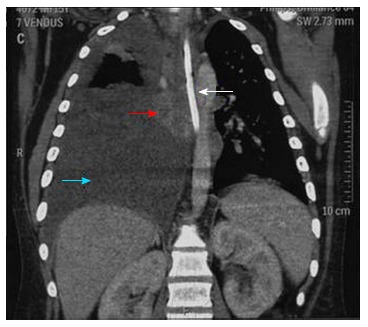

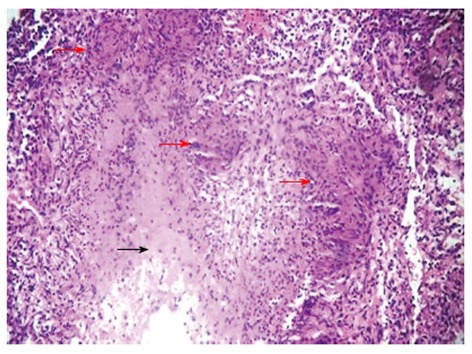

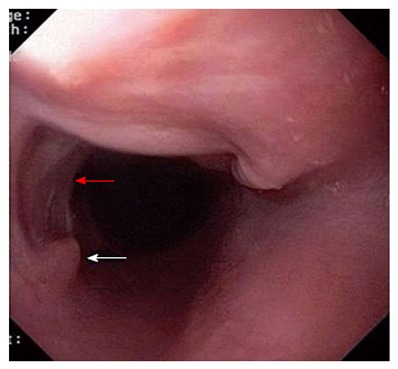

A 15-year-old male presented to the emergency room with five bouts of hematemesis and melena since past 2 d. There was no history of dysphagia, dyspnea, cough, abdominal pain or syncope. On examination his pulse was 110 beats per minute and blood pressure 90/60 mmHg. He appeared pale. Rest of the examination was unremarkable. Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL with normal blood chemistry. Human immunodeficiency virus screening antibody was negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 72 mm in the first hour. Patient was resuscitated and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed which revealed an eccentric ulcerative lesion involving 50% of circumference of the esophagus at 26 cm from the incisors (Figure 1). Biopsy of the ulcer margin was sent for histopathological examination. It revealed caseating epitheloid granulomas with lymphocytic infiltrate suggestive of tuberculosis (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax showed thickening of the mid-esophagus with enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in the subcarinal region compressing the esophagus along with moderate right sided pleural effusion (Figure 3). Polymerase chain reaction of the tissue was highly specific for mycobacterium tuberculosis. Diagnostic thoracocentesis revealed a turbid pleural exudates with pH = 7.38, glucose = 72 mg/dL, total protein = 4.3 mg/dL, total cells = 2200/mm3, consisting of 80% lymphocytes and 20% polymorphonuclear cells and lactate dehydrogenase = 724 U/L. Pleural fluid adenosine deaminase was 69 U/L, while smears, cultures and cytology, were negative. Patient was initiated on a four-drug antitubercular therapy (Rifampicin, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol) with marked improvement in his symptoms. Repeat EGD after 6 mo showed only scarring and mucosal tags with complete resolution of the ulcer (Figure 4) and chest X-ray showed complete resolution of pleural effusion.

Figure 1.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showing eccentric ulcerative lesion involving 50% of circumference of the esophagus (white arrow).

Figure 2.

Computerised tomography of the thorax showing thickening of the mid-esophagus (red arrow) along with Ryle’s tube in situ (white arrow). Right sided pleural effusion seen (blue arrow).

Figure 3.

Histopathological examination of esophageal ulcer biopsy showing epitheloid cell granulomas (red arrows) with caseation (black arrow) in the exudate suggestive of esophageal tuberculosis (HE stain x 10).

Figure 4.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy after 6 mo of anti-tuberculosis therapy showing resolution of esophageal ulcer along with scarring (red arrow) and mucosal tags (white arrow).

DISCUSSION

Esophageal tuberculosis is very rare and primary esophageal tuberculosis is seemingly even more exceptional. Esophageal tuberculosis is considered primary when there is no other detectable tubercular site and secondary when the esophagus is involved by spread from adjacent structures. Primary tuberculosis of the esophagus is extremely rare, perhaps owing to intrinsic protective mechanisms, such as stratified epithelial lining, presence of saliva. Besides, mucous coated tubular structure, peristalsis discourages stasis and mucosal invasion by organisms, which needs a physiologically stable environment. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the spread of infection to the esophagus, resulting in secondary esophageal tuberculosis: (1) infection of the esophageal mucosa from swallowed tuberculous sputum; (2) contiguous extension from laryngeal and pharyngeal lesions; (3) contiguous extension from other adjacent infected structures, such as the mediastinum, hilar lymph nodes or vertebrae; (4) retrograde lymphatic spread; and (5) hematogenous infection in the course of generalized disseminated miliary tuberculosis[2].

Common site of tubercular involvement is mid- esophagus, near carina due to proximity to mediastinal lymph nodes[6]. Damtew et al[7] in an analysis of 19 cases of esophageal tuberculosis, found that the majority of patients had direct extension from an adjacent caseous mediastinal or hilar lymph node. Most of these cases were diagnosed late and showed predominant involvement of the upper or middle third of the esophagus.

Three histomorphologically distinct types exist: (1) Ulcerous type (most common): mycobacteria initially involve submucosa of esophagus followed by formation of tubercle. As the disease progresses, caseous necrosis occurs within the nodule, followed by ulceration. Usually it is a superficial ulcer with pale grey purulent base, rough, irregular edge, only involving the mucosa and submucosa. The more serious ulcers occur rarely, often can penetrate the muscle layer, break through the esophageal adventitia resulting in esophageal perforation, esophagomediastinal fistula or esophagopleural fistula. Invasion of the trachea results in tracheoesophageal fistula. Death due to massive hemorrhage can occur due to aortoesophageal fistula. Esophageal tuberculous ulcer often has a self-healing tendency due to proliferation of fibrous tissue and scar formation, leading to local esophageal stenosis; (2) Hyperplastic type: is due to excessive amount of tuberculous granulation tissue and fibrous tissue hyperplasia. Sometimes due to massive hyperplasia, there can be false tumor-like mass (pseudotumor) formation into the esophageal lumen, resulting in luminal narrowing; and (3) Granular esophageal tuberculosis (least common): occurs in the severe systemic disease where the mucosa and submucosa show many gray-white nodules[8].

Esophageal tuberculosis presents commonly with dysphagia, cough, chest pain in addition to fever and weight loss, which might simulate esophageal malignancy. Presentation with complications is rare[2]. Hematemesis most often is due to arterioesophageal fistula with grave prognosis. In this patient upper gastrointestinal bleeding was due to ulceration in the mid-esophagus due to erosion of tuberculous subcarinal lymph nodes.

Diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis is difficult and a high index of suspicion is required. Plain radiography of the chest and CT scan could reveal pulmonary or mediastinal lymph node involvement. CT scan may also reveal thickening of the mid-esophagus as in our case. Endoscopy is valuable to diagnose the lesion and for achieving biopsy for histopathology and isolating the organism[6]. Histology shows epithelioid granuloma with Langhans cells and central caseous necrosis. Classical granulomas are seen only in 50% of cases, whereas acid fast bacilli are demonstrated in less than 25%[9]. Endoscopic mucosal biopsy has sensitivity of 22% as reported by Mokoena et al[2]. Recently, cytology and polymerase chain reaction have also proven useful in cases where the initial biopsies showed non-specific changes[10].

Anti-tubercular chemotherapy (Rifampicin, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol) for 6 to 9 mo is the main stay in the treatment. Surgical intervention is warranted if bleeding persists or gets complicated with perforation or fistula formation occur.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Samarasam I, Teramoto-Matsubara OT S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Marshall JB. Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:989–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokoena T, Shama DM, Ngakane H, Bryer JV. Oesophageal tuberculosis: a review of eleven cases. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:110–115. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.796.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upadhyay AP, Bhatia RS, Anbarasu A, Sawant P, Rathi P, Nanivadekar SA. Esophageal tuberculosis with intramural pseudodiverticulosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:38–40. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman RM, Fleshner PR, Lajam FE, Kim U. Esophageal tuberculosis: a rare presentation with hematemesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang HY, Lin TS, Cheng CY, Talbot AR. Esophageal tuberculosis: a rare presentation with massive hematemesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2344–2346. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon AH, Marshall JB. Esophageal tuberculosis: definitive diagnosis by endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:174–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damtew B, Frengley D, Wolinsky E, Spagnuolo PJ. Esophageal tuberculosis: mimicry of gastrointestinal malignancy. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:140–146. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosario MT, Raso CL, Comer GM. Esophageal tuberculosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1281–1284. doi: 10.1007/BF01537279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seivewright N, Feehally J, Wicks AC. Primary tuberculosis of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:842–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara T, Yoshida Y, Yamada S, Kawamata H, Fujimori T, Imawari M. A case of primary esophageal tuberculosis diagnosed by identification of Mycobacteria in paraffin-embedded esophageal biopsy specimens by polymerase chain reaction. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:74–78. doi: 10.1007/s005350300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]