Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a common pathogen isolated from patients with nosocomial infections. Due to its intrinsic and acquired antimicrobial resistance, limited classes of antibiotics can be used for the treatment of infection with P. aeruginosa. Of these, the carbapenems are very important; however, the occurrence of carbapenem-resistant strains is gradually increasing over time. Deficiency of the outer membrane protein OprD confers P. aeruginosa a basal level of resistance to carbapenems, especially to imipenem. Functional studies have revealed that loops 2 and 3 in the OprD protein contain the entrance and/or binding sites for imipenem. Therefore, any mutation in loop 2 and/or loop 3 that causes conformational changes could result in carbapenem resistance. OprD is also a common channel for some amino acids and peptides, and competition with carbapenems through the channel may also occur. Furthermore, OprD is a highly regulated protein at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels by some metals, small bioactive molecules, amino acids, and efflux pump regulators. Because of its hypermutability and highly regulated properties, OprD is thought to be the most prevalent mechanism for carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa. Developing new strategies to combat infection with carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa lacking OprD is an ongoing challenge.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, OprD, Carbapenem

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a significant cause of nosocomial pneumonia in North America being isolated from about 20% of cases (Hoban et al., 2003). Furthermore, P. aeruginosa is the most prevalent pathogen isolated from patients with secondary infection following severe injury or burns (Keen et al., 2010; Song et al., 2001). The mortality of blood stream infections due to P. aeruginosa reaches as high as 50% (Lautenbach et al., 2010). Intrinsic and acquired resistance to antimicrobial agents is partly to blame for the high mortality rate in patients infected with P. aeruginosa. Among available antibiotics, carbapenems (e.g. imipenem and meropenem) are frequently used for treatment of P. aeruginosa infections (Lautenbach et al., 2010). Unfortunately, their use has resulted in increasing resistance with rates as high as 21.1% (NNIS, 2004).

To date, 3 carbapenem resistance mechanisms have been identified including reduced carbapenem influx due to changes in the expression of outer membrane porins (OprD) (Yoneyama and Nakae, 1993), carbapenemases released from the pathogen (Borgianni et al., 2011; Hocquet et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2010), and efflux pump overexpression (Quale et al., 2006). Each resistance mechanism results in a different resistance pattern. P. aeruginosa with reduced OprD protein expression exhibit moderate resistance to imipenem, whereas efflux pump overexpression combined with loss of OprD renders P. aeruginosa highly resistant to not only imipenem, but also to meropenem and doripenem (Quale et al., 2006; Hammami et al., 2009). Deficient OprD expression usually results in a basal level of antibiotic resistance in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Most carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains are defective in expression of OprD (Naenna et al., 2010). A recent systematic review evaluated randomized, controlled trials of P. aeruginosa pneumonia treated with imipenem or comparators and found that clinical success and microbiologic eradication rates for combating P. aeruginosa were lower in imipenem-treated patients than in comparators (Zilberberg et al., 2010). In addition, initial and treatment-emergent resistance was more likely with imipenem than with comparator regimens.

The history of OprD identification and its function

Imipenem has been approved for clinical use since 1987 in the USA (Zhanel et al., 2007). Due to its intrinsic resistance to nearly all β-lactamases, it is used as the last line of defense in antibiotic therapy for infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa. However, the discovery of resistance to imipenem was concurrent with or even earlier than its approval (Quinn et al., 1986; Lynch et al., 1987; Büscher et al., 1987). The characteristic of imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa was identified as lack of a 45–~49 kilodalton (kDa) outer membrane protein, OprD. The oprD-coding gene was mapped between 71 and 75 min on the P. aeruginosa PAO1 chromosome, and the OprD protein was shown to be coded by 1332-bp nucleotides (Quinn et al., 1991; Yoneyama et al., 1992). Its shared similarity to members of the porin family ranges from 41% to 58%, and it was proposed that OprD would thus have the general topology of other porin proteins. Typical porin proteins contain a 16-strand transmembrane β-barrel structure comprised of 7 short-turn sequences on the periplasmic side which act as hinges to connect 8 loop structures on the external surface (Ochs et al., 2000; Huang et al., 1995).

Unlike the porin protein OmpF in Escherichia coli, the channel formed by OprD is narrower, which causes a lower outer membrane permeability in P. aeruginosa than in E. coli (Ochs et al., 1999b). In addition to carbapenems, OprD acts as a specific channel for basic amino acids and some small peptides (Trias and Nikaido, 1990a, b). In the deduced topology of the OprD protein, external loops 2 and 3 were determined as entrances for basic amino acids and binding sites for imipenem. Furthermore, any substitution or deletion within loop 2 and loop 3 that results in changes in conformation can cause imipenem resistance (Ochs et al., 2000; Huang et al., 1995; Huang and Hancock, 1996; Pirnay et al., 2002; Chevalier et al., 2007). Functional deletion of loop 2 at H729 (Huang and Hancock, 1996) induced partial resistance to imipenem and meropenem compared to the parental strain, indicating that uptake of these antibiotics was affected by this deletion. In large bilayer membranes with purified OprD, KCl conductance was blocked by imipenem. In contrast, there was no decrease in conductance with imipenem-treated OprD lacking loop 2, suggesting that imipenam binds to sites in loop 2 to block channel function.

When one of the carbapenems, imipenem, meropenem, or ER-35786 (a parenteral 1-beta-methyl carbapenem which has potent antipseudomonal activity) were added to wild-type PAO1 at a dose of 2- to 8-fold of MIC, all colonies displayed resistance to the 3 carbapenems and exhibited oprD gene mutation and OprD protein loss to some degree. When the OprD-deficient strain PASE1 was subjected to the same procedure, interesting differences were found. There was no colony growth on nutrient agar containing 48 μg/ml imipenem, while resistant colonies were selected on agar containing 16 μg/ml meropenem or 8 μg/ml ER-35786. The resistant phenotype for the selected mutant strain showed a slightly increased MIC of meropenem and ER-35786, whereas the MIC of imipenem was unchanged. The resistance mechanisms included nalB-type mutants, overexpression of MexAB-OprM, and decreased expression of a suspected novel porin protein (Köhler et al., 1999a). Taken together, these results suggest that loss of OprD might be the first antibiotic resistance mechanism induced by selective pressure of carbapenem, while multiple additional resistance mechanisms could appear when an OprD-deficient P. aeruginosa is faced with the further pressure of carbapenem. Moreover, other resistance mechanisms, such as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), may be concurrent with the OprD mutations and account for additional carbapenem resistance. As shown by Farra et al. (2008), PBPs play a role in carbapenem resistance either through binding to antimicrobial agents or through downregulation of oprD gene expression in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa.

Deletion of loops 3 and 4 in OprD results in failed expression in either E. coli or P. aeruginosa (Huang et al., 1995). After adjustment in a topological model, the sites for functional loop-3 deletion were corrected from the position of 156G to 163P and the expression of this variant failed to reconstitute imipenem susceptibility. However, loop 3 does not appear to be a direct binding site for imipenem since deletion of loop 3 does not alter the inhibition of KCl conductance by imipenem (Ochs et al., 2000). Therefore, loop 3 is more likely to serve as a passage channel within OprD for imipenem, but not a direct binding site. The mechanism by which imipenem binds to loop 2 and then passes through loop 3 within OprD is still undetermined.

Besides loop 2 and loop 3, other domains in OprD have been intensively studied (Huang et al., 1995; Huang and Hancock, 1996). P. aeruginosa with OprD proteins containing deletions of loops L1, L5, L6, L7, and L8 showed similar imipenem susceptibility compared to P. aeruginosa H729 overexpressing wild-type OprD (pXH2), suggesting that loop 1, loop 5, loop 6, loop 7, and loop 8 are not involved in the passage of imipenem. Furthermore, the deletion of loop 5, loop 7, and loop 8 resulted in increased susceptibility to β-lactams, quinolones, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline, indicating that these 3 loops likely reduce intracellular accumulation of some antibiotics (Pirnay et al., 2002). Amino acid substitutions within loop 7 result in increased meropenem susceptibility with a 4-fold decrease in MIC (Epp et al., 2001).

Interestingly, OprD works not only as channel for some amino acids and peptides, but also as a protease. It was confirmed that purified protein OprD hydrolyzed several synthetic peptides in a manner consistent with Michaelis–Menten Kinetics, and activity of this protease can be inhibited by a specific serine protease inhibitor (Yoshihara et al., 1996). This activity was then identified to be associated with residues of His156, Asp208, and Ser296, which are similar to the catalytic triad of residues in trypsin and chymotrypsin (Yoshihara et al., 1998). However, the X-ray crystal structure of the OprD protein reported by Biswas et al. (2007) refuted this finding since the proposed catalytic triad is too far apart and located on the wrong positions to be part of a catalytic triad. According to the X-ray crystal structure, OprD protein is a monomeric 18-stranded β-barrel that forms 9 loops. A very narrow pore constriction with a positively charged basic ladder on one side and an electronegative pocket on the other side was described in the crystal structure. As shown in the crystal structure of this protein, the short length of strand 5 and strand 6 and the absolutely conserved amino acids (Gly116 and Gly139) result in the inward shape of loop 3. This structure leads to the functional importance in loop 3. According to the crystal structure of OprD, some proposed sites in functional studies of specific loops were incorrectly deduced in the previously published literatures (as shown in the Table 1). To date, there are no functional studies based on the crystal structure. This corrected structure of OprD not only provides a way to study substrate selectivity and specificity, but also gives a chance to explore new drugs against P. aeruginosa.

Table 1.

Putative sites in OprD that affect antibiotic sensitivity.

| Loops | Sites in the crystal structures for loops |

Sites for deletion experiments |

Susceptible changes for carbapenems and β-lactams (compared to PAO1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop 1 | 32G-39R | 26Y-33K | No effect |

| Loop 2 | 75G-98S | 73L-80T | Increase of imipenem MIC |

| 79K-86P | Increase of imipenem MIC | ||

| 83G-90D | Increase of imipenem MIC | ||

| 84N-91Q | Increase of carbapenems MIC | ||

| 93P-100A | Increase of imipenem MIC | ||

| Loop 3 | 119Q-137A | 146E-153E | Diminished but observable OprD expression |

| 156H-163P | Increase of imipenem MIC | ||

| Loop 4 | 158T-183S | 196N-199A | No stable OprD expression |

| Loop 5 | 207E-209I | 240D-247G | Susceptibility to β-lactam including carbapenems |

| Loop 6 | 240D-249I | 288N-291G | No effect |

| Loop 7 | 274V-314K | 349M-356Y | Susceptibility to β-lactam including carbapenems |

| Loop 8 | 345D-364D | 398N-405D | Susceptibility to β-lactam including carbapenems |

| Loop 9 | 398N-406Q | – | – |

Competition between imipenem and amino acids passing through OprD

Since OprD is a common channel for the intake of basic amino acids, peptides, and carbapenems, it is reasonable that a competitive phenomenon may appear among these substances when they pass through the channel simultaneously. In the presence of several basic amino acids including histidine, arginine, and lysine and its analogs, the inhibition rate for imipenem penetration increased from 48% to 80%. Peptides containing lysine also inhibited the penetration of imipenem (Trias and Nikaido, 1990b). This suggests bacterial nutrient sources that contain different concentrations of amino acids, such as serum and culture medium, will affect the susceptibility of carbapenems. This was confirmed in studies of the efficacy of carbapenems against P. aeruginosa in different culture media. Culture medium containing basic amino acids significantly increased the MIC of carbapenems against clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, while the MIC of ceftazidime and aztreonam was not affected by adding basic amino acids (Muramatsu et al., 2003). In MMA (minimal medium agar) with lysine, an OprD-containing strain of PAO1 had increased MIC’s to carbapenems by 8–16-fold. However, an OprD-deficient strain only increased MIC of imipenem and meropenem by 2-fold in the same medium. Furthermore, PAO1 and its OprD-deficient mutants cultured in MMA medium were more susceptible to carbapenems compared to the same strain cultured in Mueller–Hinton II agar (MHA) and other mediums. The MIC of non-carbapenem antibiotics was not affected by changing the gradient of the medium (Fukuoka et al., 1991). In addition, an ex vivo model confirmed that penipenem and imipenem had lower activity against PAO1 in human serum supplemented with l-lysine compared to human serum without l-lysine. However, both antibiotics showed higher activity against P. aeruginosa in human serum than in Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) media. Despite significant changes in the activity of carbapenems against PAO1 in different biological fluids and mediums, OprD-deficient PAO1 exhibited similar susceptibility of carbapenems in different culture backgrounds, consistent with the idea that competition occurs between carbapenems and some amino acids when they pass through OprD (Fukuoka et al., 1993). These results suggest that the in vitro MIC determined in different culture conditions may not reflect the in vivo “true MIC” of carbapenems during human infections. Clinicians should take caution that the true breakpoint for MICs determined in the clinical laboratory may be erroneous when tested in certain basic amino acid-enriched culture mediums.

Although there are no reports of carbapenem resistance due to metabolic disorders or differences in available amino acids, different bacterial growth conditions and environments may affect the efficacy of carbapenems. For example, compared to non-cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, lungs of CF patients were shown to be colonized with a high percentage of hyper-mutable P. aeruginosa that are moderately resistant to carbapenems (Oliver et al., 2000). In CF patients, P. aeruginosa develop stepwise mutations in OprD even in the absence of carbapenems (Ballestero et al., 1996; Wolter et al., 2008). Although frequent exposure to antibiotics may explain some hypermutation, the altered bronchial environment in CF could lead to selective pressures to change OprD expression (Barth and Pitt, 1996; Thomas et al., 2000).

The regulations of OprD expression

Upregulation of OprD expression

In theory, exploring how to up-regulate OprD expression might be therapeutically useful for carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. Basic amino acids not only competitively pass through the OprD channel with carbapenems, but also induce OprD protein expression. When arginine, histidine, glutamate, or alanine are used as the sole source of carbon or nitrogen, the transcription level of OprD is increased by 3.5- to 5.6-fold compared to the minimal medium supplemented with succinate. Arginine-responsive regulator (ArgR) can bind to the operator region of oprD and regulate OprD expression in a dose-dependent manner. Besides arginine, OprD expression is also regulated by other amino acids, including glutamate, histidine, and alanine through an unknown, non-ArgR-dependent pathway (Ochs et al., 1999a).

Downregulation of OprD

Trace metals play an important down-regulatory role in OprD expression (Perron et al., 2004; Caille et al., 2007; Conejo et al., 2003). Imipenem has an increased MIC for P. aeruginosa in the presence of sublethal concentrations of zinc. In zinc-treated bacteria, a V194L substitution was observed in the sensor protein CzcS, which increased expression of the heavy metal efflux pump (CzcCBA) and reduced expression of OprD protein. Another CzcCBA-regulated gene, CzcR, does not cause upregulation of CzcCBA; however, its overexpression suppresses the expression of OprD (Conejo et al., 2003; Perron et al., 2004). Hence, zinc increases the expression of efflux pump CzcCBA and decreases the expression of OprD through the two-component regulator CzcS–CzcR in P. aeruginosa. Copper can affect carbapenem resistance; however, the mechanism for copper-induced carbapenem resistance is not the same as with zinc. Besides the CzcR–CzcS regulatory system, another two-component regulator copR–copS is involved in Cu tolerance of P. aeruginosa and is responsible for decreased OprD expression (Caille et al., 2007).

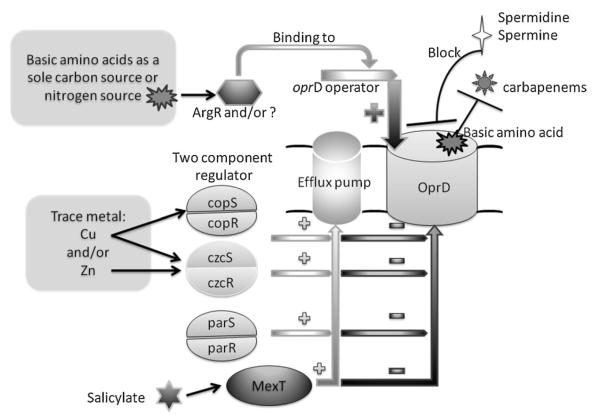

In addition to heavy metals, P. aeruginosa also actively pumps antimicrobial compounds through a series of efflux pumps. In some circumstances, P. aeruginosa can selectively extrude antibiotics by opening these efflux pumps. This is contrary to the mechanism of OprD-mediated resistance. In the clinical setting, overexpression of efflux pumps and defects in OprD function synergistically increase the MIC of carbapenems compared to either mechanism alone. The well-known multidrug efflux system MexEF-OprN and its regulator MexT can also be involved in negatively regulating OprD expression (Köhler et al., 1997, 1999b; Ochs et al., 1999b). A MexEF-OprN overexpressing strain exhibited a reduction in OprD expression, but not an increased MIC of imipenem. Interestingly, when the MexEF-OprN regulatory region MexT was cloned into MexE mutant of PAO1, imipenem resistance appeared to be due to the reduction of OprD expression (Köhler et al., 1997). Like the metal-responsive two-component regulator, MexT positively regulates the expression of MexEF-OprN and negatively regulates oprD expression at both the post-transcriptional and the transcriptional level (Köhler et al., 1999b). However, it is not known whether MexT directly regulates oprD as a binding site in the oprD promoter has not been determined. Therefore, it is possible that MexT regulates oprD by an indirect mechanism. Recently, another two-component regulatory system named ParR-ParS was described that induces P. aeruginosa resistance to 5 classes of antibiotics including imipenem, cefepime, colistin, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones. This regulatory system seems to work through increased MexXY expression, repressed oprD expression, and LPS modification (Muller et al., 2011). Salicylate, a plant-derived compound known as a membrane-permeative weak acid, can suppress the synthesis of certain outer membrane proteins in a number of Gram-negative bacteria. It can induce a 16-fold increased MIC of imipenem and decrease oprD expression at the transcriptional level by 3.3-fold, which is very similar to the effects seen in a mexT overexpressing strain, suggesting salicylate suppresses oprD transcription partly through mexT (Ochs et al., 1999b). Unlike salicylate, the polycationic compounds spermidine and spermine directly block the OprD channel, elevating the MIC for imipenem (Kwon and Lu, 2007). We summarize the known mechanisms underlying the regulation of OprD expression in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Regulators of expression of OprD and factors affecting the bacterial penetration of carbapenems. Basic amino acids acting as sole carbon and/or nitrogen source drive ArgR or other regulators that bind to the oprD gene operator and increase the expression of OprD. OprD expression is suppressed by two-component regulators, including copSR, czcSR, parSR, and efflux pump regulator MexT. These regulators also increase the expression of specific efflux pumps (as shown in the figure, “+” means increase, “−” means decrease). Basic amino acids can directly compete with carbapenem for penetration through the OprD channel. Some molecules, such as spermidine and spermine, can block the OprD channel and affect entry of carbapenems. Salicylate decreases the expression of OprD through regulating the expression of MexT.

Potential therapy for OprD-defective P. aeruginosa strains

Due to high bactericidal activity, carbapenems can contribute to clinical success against P. aeruginosa. Unfortunately, the emergence of OprD-defective strains reduces efficacy of these antibiotics. Fortunately, there are some strategies that can be used to overcome resistance to conventional carbapenems.

Doripenem

Doripenem is a new parental carbapenem approved by the FDA for its clinical use in complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated urinary tract infections (Lascols et al., 2010). Doripenem, similar to meropenem, is stable from the hydrolysis of human renal dehydropeptidase I (Mushtaq et al., 2004). Although it is superior to imipenem in pharmacokinetics, doripenem has efficacy in only 18.2% of imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (Lascols et al., 2010). However, doripenem induces susceptible P. aeruginosa to generate adaptive changes and loss of OprD at a lower frequency compared to other carbapenems (Mushtaq et al., 2004; Sakyo et al., 2006). In combination with sub-inhibitory doses of fluoroquinolone, doripenem inhibits the bacterial growth while meropenem selects for higher rates of drug-resistant mutations (Tanimoto et al., 2008). Louie et al. (2010) recently evaluated methods of administering carbapenems to wild-type and resistant P. aeruginosa. This group used an in vitro hollow fiber-infected model to determine bacterial killing and resistance. In general, doripenem was more potent than imipenem in wild-type isolates and had lower MIC (8-fold) against oprD-mutated strains. A regimen of prolonged (4 h), high-dose (1 g) doripenem infusion for every 8 h was most potent for bacterial killing and the suppression of bacterial resistance (Louie et al., 2010).

Combination of fluoroquinolone with carbapenems

Although a sub-inhibitory concentration of fluoroquinolone increases the frequency of carbapenem-selected mutants (Tanimoto et al., 2008), the combination of high-dose fluoroquinolone with carbapenems works well in the treatment of both wild-type P. aeruginosa and mutant P. aeruginosa. A high dose (1 g) of imipenem can be administered every 12 h and combined with 750 mg levofloxacin once a day to combat the emergence of a double mutant strain lacking OprD and overexpressing MexXY (Lister and Wolter, 2005; Lister et al., 2006).

CXA-101

CXA-101, formerly named FR264205, is a novel parenteral 3′-aminopyrazolium cephalosporin. It exhibits higher efficacy against P. aeruginosa and 8–~16 folds lower MIC than those of ceftazidime, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin both in vitro and in vivo (Takeda et al., 2007). For CF patients infected with multiresistant P. aeruginoas, the MIC of CXA-101 was 2–16-fold below those of ceftazidime. Hence, CXA-101 has full activity against OprD-defective strains (Livermore et al., 2009). Furthermore, for the double mutant strain of OprDAmpD and OprD-PBP4, CXA-101 remained at full efficacy at the MIC of 0.5 μg/ml (Moya et al., 2010). Therefore, CXA-101 is a promising and powerful antibiotic for antipseudomonal activity, especially against resistant P. aeruginosa. Additional studies are needed to evaluate its safety in clinical trials.

Bio-peptide used synergistically with antibiotics

The small lactoferricin-derived peptides P2-15 and P2-27 have synergistic antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa in vitro and/or in vivo. Importantly, the combination of P2-15 or P2-27 with antibiotics can reverse the resistance of P. aeruginosa to susceptible strains and counteract several mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, including loss of OprD (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2011). At present, it is uncertain whether peptides that enhance the permeability of P. aeruginosa are safe enough for human cells and tissue. Thus, a number of steps are still required for determining the usefulness of this approach in humans.

Conclusion

OprD is a well-characterized channel for imipenem influx. Defective OprD confers P. aeruginosa a basal level of resistance to carbapenems and thus causes difficulty in clinical practice. Therefore, continued research needs to be done regarding OprD’s function and regulation. In general, sites in loop 2 and loop 3 within OprD are responsible for binding and passage of carbapenems as well as some basic amino acids, such as histidine, lysine, and arginine. Several defined pathways are involved in the regulation of OprD expression, including two-component regulatory elements and basic amino acids. Studies involving OprD regulatory mechanisms and the recently characterized crystal structure are useful for exploring the new therapeutic targets. Despite the difficulty in treating P. aeruginosa lacking OprD, possibilities exist to combat resistance by introducing new antibiotics, combination therapies, and novel approaches.

References

- Ballestero S, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Villaverde R, Escobar H, Pérez-Díaz JC, Baquero F. Carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1996;38:39–45. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AL, Pitt TL. The high amino-acid content of sputum from cystic fibrosis patients promotes growth of auxotrophic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Med. Microbiol. 1996;45:110–119. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-2-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Mohammad MM, Patel DR, Movileanu L, van den Berg B. Structural insight into OprD substrate specificity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:1108–1109. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgianni L, Prandi S, Salden L, Santella G, Hanson ND, Rossolini GM, Docquier JD. Genetic context and biochemical characterization of IMP-18 metallo-beta lactamase identified in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:140–145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00858-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher KH, Cullmann W, Dick W, Opferkuch W. Imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa resulting from diminished expression of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987;31:703–708. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille O, Rossier C, Perron K. A copper-activated two-component system interacts with zinc and imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:4561–4568. doi: 10.1128/JB.00095-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier S, Bodilis J, Jaouen T, Barray S, Feuilloley MGJ, Orange N. Sequence diversity of the OprD protein of environmental Pseudomonas strains. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:824–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conejo MC, García I, Martínez-Martínez L, Picabea L, Pascual Á. Zinc eluted from siliconized latex urinary catheters decreases OprD expression, causing carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2313–2315. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2313-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp SF, Köhler T, Plésiat P, Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Frey J, Pechère JC. C-terminal region of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane porin OprD modulates susceptibility to meropenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1780–1787. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1780-1787.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farra A, Islam S, Strålfors A, Sörberg M, Wretlind B. Role of outer membrane protein OprD and penicillin-binding proteins in resistance of Pseudomona aeruginosa to imipenem and meropenem. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2008;31:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka T, Masuda N, Takenouchi T, Sekine N, Iijima M, Ohya S. Increase in susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to carbapenem antibiotics in low-amino acid media. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:529–532. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka T, Ohya S, Narita T, Katsuta M, Iijima M, Masuda N, Yasuda H, Trias J, Nikaido H. Activity of the carbapenem panipenem and role of the OprD (D2) protein in its diffusion through the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:322–327. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammami S, Ghozzi R, Burghoffer B, Arlet G, Redjeb S. Mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in non-metallo-beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a Tunisian hospital. Pathol. Biol. 2009;57:530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoban DJ, Biedenbach DJ, Mutnick AH, Jones RN. Pathogen of occurrence and susceptibility patterns associated with pneumonia in hospitalized patients in North America: results of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance study (2000) Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003;45:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocquet D, Plésiat P, Dehecq B, Mariotte P, Talon D, Bertrand X. Nationwide investigation of extended spectrum beta lactamase, metallo-beta-lactamases, and extended spectrum oxacillinases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeurginosa strains in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3513–3515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01646-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Jeanteur D, Pattus F, Hancock REW. Membrane topology and site specific mutagenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa porin OprD. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Hancock RW. The role of specific surface loop regions in determining the function of the imipenem-specific pore protein OprD of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3085–3090. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3085-3090.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen EF, III, Robinson BJ, Hospenthal DR, Aldous WK, Wolf SE, Chung KK, Murray CK. Incidence and bacteriology of burn infections at a military burn center. Burns. 2010;36:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TH, Khoo CT, Tan TT, Arshad MA, Ang LP, Lau LJ, Hsu LY, Ooi EE. Multilocus sequence types of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Singapore carrying metallo-beta-lactamase genes, including the novel bla(IMP-26) gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2563–2564. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01905-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T, Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Henze U, Gotoh N, Curty LK, Pechère JC. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T, Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Epp SF, Pechère JC. Carbapenem activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: respective contributions of OprD and efflux systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999a;43:424–427. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T, Epp SF, Curty LK, Pechère JC. Characterization of MexT, the regulator of the MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1999b;181:6300–6305. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6300-6305.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon DH, Lu CD. Polyamine effects on antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2070–2077. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01472-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascols C, Legrand P, Mérens A, Leclercq R, Armand-Lefevre L, Drugeon HB, Kitzis MD, Muller-Serieys C, Reverdy ME, Roussel-Delvannez M, Moubareck C, Lemire A, Miara A, Gjoklaj M, Soussy CJ. In vitro antibacterial activity of doripenem against clinical isolates from French teaching hospitals: proposition of zone diameter breakpoints. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010;30:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbach E, Synnestvedt M, Weiner MG, Bilker WB, Vo L, Schein J, Kim M. Imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: emergence, epidemiology, and impact on clinical and economic outcomes. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:47–53. doi: 10.1086/649021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister PD, Wolter DJ. Levofloxacin–imipenem combination prevents the emergence of resistance among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:S105–S114. doi: 10.1086/426190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Wickman PA, Reisbig MD. Levofloxacin/imipenem prevents the emergences of high-level resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains already lacking susceptibility to one or both drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:999–1003. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore DM, Mushtaq S, Ge Y, Warner M. Activity of cephalosporin CXA-101 (FR264205) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia group strains and isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009;34:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie A, Bied A, Fregeau C, van Scoy B, Brown D, Liu W, Bush K, Queenan AM, Morrow B, Khashab M, Kahn JB, Nicholson S, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. Impact of different carbapenems and regimens of administration on resistance emergence for three isogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with differing mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2638–2645. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01721-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MJ, Drusano GL, Mobley HLT. Emergence of resistance to imipenem in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1892–1896. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya B, Zamorano L, Juan C, Pérez JL, Ge Y, Oliver A. Activity of a new cephalosporin, CXA-101 (FR264205), against β-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants selected in vitro and after antipseudomonal treatment of intensive care unit patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1213–1217. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01104-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C, Plésiat P, Jeannot K. A two-component regulatory system interconnects resistance to polymyxins, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and beta-lactams in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1211–1221. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01252-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Horii T, Morita M, Hashimoto H, Kanno T, Maekawa M. Effect of basic amino acids on susceptibility to carbapenems in clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;293:191–197. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq S, Ge Y, Livermore DM. Doripenem versus Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro: activity against characterized isolates, mutants, and transconjugants and resistance selection potential. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3086–3092. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3086-3092.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naenna P, Noisumdaeng P, Pongpech P, Tribuddharat C. Detection of outer membrane porin protein, an imipenem influx channel, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2010;41:614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System National nosocomial infections surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2004;32:470–485. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs MM, Lu CD, Hancock REW, Abdelal AT. Amino acid-mediated induction of the basic amino acid-specific outer membrane porin OprD from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1999a;181:5426–5432. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5426-5432.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs MM, McCusker MP, Bains M, Hancock REW. Negative regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane porin OprD selective for imipenem and basic amino acids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999b;43:1085–1090. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs MM, Bains M, Hancock REW. Role of putative loops 2 and 3 in imipenem passage through the specific porin OprD of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1983–1985. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1983-1985.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A, Canton R, Campo P, Baquero F, Blazquez J. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science. 2000;288:1251–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron K, Caille O, Rossier C, van Delden C, Dumas JL, Köhler T. CzcR–CzsS, a two-component system involved in heavy metal and carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8761–8768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirnay JP, De Vos D, Mossialos D, Vanderkelen A, Cornelis P, Zizi M. Analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oprD gene from clinical and environmental isolates. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4:872–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quale J, Bratu S, Gupta J, Landman D. Interplay of efflux system, ampC and oprD expression in carbapenem resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1633–1641. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1633-1641.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JP, Dudek EJ, DiVincenzo CA, Lucks DA, Lerner SA. Emergence of resistance to imipenem during therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J. Infect. Dis. 1986;154:289–294. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JP, Darzins A, Miyashiro D, Ripp S, Miller RV. Imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO: mapping of the OprD2 gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:753–755. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.4.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakyo S, Tomita H, Tanimoto K, Fujimoto S, Ike Y. Potency of carbapenems for the prevention of carbapenem resistant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antibiot. 2006;59:220–228. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez S, Japelj B, Jerala R, Moriyón I, Fernández Alonso MF, Leiva J, Blondelle SE, Andrä J, Brandenburg K, Lohner K, Martínez de Tejada GM. Structural features governing the activity of lactoferricin-derived peptides that act in synergy with antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:218–228. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00904-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Lee KM, Kang HJ, Shin DH, Kim DK. Microbiologic aspects of predominant bacteria isolated from the burn patients in Korea. Burns. 2001;27:136–139. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Nakai T, Wakai Y, Ikeda F, Hatano K. In vitro and in vivo activities of a new cephalosporin, FR264205, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:826–830. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00860-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto K, Tomita H, Fujimoto S, Okuzumi K, Ike Y. Fluoroquinolone enhances the mutation frequency for meropenem-selected carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but use of the high-potency drug doripenem inhibits mutant formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3795–3800. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00464-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SR, Ray A, Hodson ME, Pitt TL. Increased sputum amino acid concentration and auxotrophy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Thorax. 2000;55:795–797. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.9.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias J, Nikaido H. Outer membrane protein D2 catalyzes facilitated diffusion of carbapenems and penems through the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990a;34:52–57. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias J, Nikaido H. Protein D2 channel of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane has a binding site for basic amino acids and peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1990b;265:15680–15684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter DJ, Acquazzino D, Goering RV, Sammut P, Khalaf N, Hanson ND. Emergence of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patient with cystic fibrosis in the absence of carbapenem therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:137–141. doi: 10.1086/588484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama H, Nakae T. Mechanism of efficient elimination of protein D2 in outer membrane of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2385–2390. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama H, Yoshihara E, Nakae T. Nucleotide sequence of the protein D2 gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1791–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara E, Gotoh N, Nishino T, Nakae T. Protein D2 porin of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane bears the protease activity. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara E, Yoneyama H, Ono T, Nakae T. Identification of the catalytic triad of the protein D2 portease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;247:142–145. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhanel GG, Wiebe R, Dilay L, Thomson K, Rubinstein E, Hoban DJ, Noreddin AM, Karlowsky JA. Comparative review of the carbapenems. Drugs. 2007;67:1027–1052. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberberg MD, Chen J, Mody SH, Ramsey AM, Shorr AF. Imipenem resistance of Pseudomonas in pneumonia: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2010;10:45–55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]