Abstract

Paclitaxel (taxol) is a first-line chemotherapy-drug used to treat many types of cancers. Neuropathic pain and sensory dysfunction are the major toxicities, which are dose-limiting and significantly reduce the quality of life in patients. Two known critical spinal mechanisms underlying taxol-induced neuropathic pain are an increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and suppressed glial glutamate transporter activities. In this study, we uncovered that increased activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3β) in the spinal dorsal horn was concurrently associated with increased protein expressions of GFAP, IL-1β and a decreased protein expression of glial glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), as well as the development and maintenance of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. The enhanced GSK3β activities were supported by the concurrently decreased AKT and mTOR activities. The changes of all these biomarkers were basically prevented when animals received pre-emptive lithium (a GSK3β inhibitor) treatment, which also prevented the development of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. Further, chronic lithium treatment, which began on day 11 after the first taxol injection, reversed the existing mechanical and thermal allodynia induced by taxol. The taxol-induced increased GSK3β activities and decreased AKT and mTOR activities in the spinal dorsal horn were also reversed by lithium. Meanwhile, protein expressions of GLT-1, GFAP and IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn were improved. Hence, suppression of spinal GSK3β activities is a key mechanism used by lithium to reduce taxol-induced neuropathic pain, and targeting spinal GSK3β is an effective approach to ameliorate GLT-1 expression and suppress activation of astrocytes and IL-1β over-production in the spinal dorsal horn.

Introduction

Paclitaxel (taxol) is a first-line chemotherapy-drug used to treat many types of cancers. Neuropathic pain and sensory dysfunction are the major toxicities, that are dose-limiting and significantly reduce the quality of life in patients (Dougherty et al., 2004, Cata et al., 2006b). Accumulating evidence indicate that altered spinal glial functions in the spinal dorsal horn play a crucial role in the genesis of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. Two known critical spinal mechanisms by which dysfunctional glial cells contribute to taxol-induced neuropathic pain are an increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012) and suppressed glial glutamate transporter activities (Weng et al., 2005, Doyle et al., 2012). Activities of AMPA and NMDA receptors in spinal dorsal horn neurons, and glutamate release from presynaptic terminals are increased by IL-1β (Kawasaki et al., 2008). Impaired glutamate uptake by glial glutamate transporters causes excessive activation of AMPA and NMDA receptors in the spinal dorsal horn (Weng et al., 2006, Weng et al., 2007, Nie and Weng, 2009) because clearance of glutamate released from presynaptic terminals and maintenance of glutamate homeostasis depend on glutamate transporters (Danbolt, 2001). Currently, it remains obscure about the mechanisms regulating glial activation, over-production of proinflammatory cytokines, and down-regulation of glial glutamate transporters in the spinal dorsal horn in taxol induced neuropathic pain.

Previous studies have shown that GSK3β is critically involved in the neuroinflammation process in many neurological diseases (Beurel et al., 2010). GSK3β is a constitutive active serine/threonine protein kinase (Beurel et al., 2010). Unlike most protein kinase, GSK3β activities are regulated mostly through the phosphorylation of Serine-9, which results in inactivation of GSK3β (Woodgett, 1990, Sutherland et al., 1993). Thus, a reduced level of phosphorylated GSK3β at serine 9 (p-GSK3β) indicates an increased GSK3β activity (Woodgett, 1990, Sutherland et al., 1993). Cortical astrocytes and microglia treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have increased GSK3β activities (decreased levels of phosphorylated GSK3β) and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while suppression of GSK3β activities attenuates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and augments the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) in vitro (Green and Nolan, 2012). Increased GSK3β activities are found in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacological suppression of GSK3β activities attenuates the production of β-Amyloid (Sun et al., 2002) in Alzheimer's disease. Pretreatment with the GSK3β inhibitor suppressed microglia activation in the spinal cord and clinical symptoms of multiple sclerosis in mice (De Sarno et al., 2008). GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn are increased in rats with morphine tolerance (Parkitna et al., 2006). The second phase of formalin-nociceptive response in mice is suppressed by pre-treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor (Martins et al., 2011). Intraperitoneal injection of GSK3β inhibitors attenuates production of TNF-α and IL-1β in the spinal cord and pre-existing neuropathic pain in mice with partial sciatic nerve ligation (Mazzardo-Martins et al., 2012). It is unknown about the role of GSK3β in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain induced by taxol.

Lithium, a classic therapeutic drug used for the treatment of bipolar disorder in clinics, is a GSK3β inhibitor (Beurel et al., 2010). Lithium has been reported to be an effective remedy for neuropathic pain. For example, thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation or chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve were attenuated by systemic administration of lithium (Banafshe et al., 2012) or intrathecal administration of lithium (Shimizu et al., 2000). Pre-emptive systemic treatment of lithium attenuates thermal hypoalgesia and axonal demyelination in peripheral nerve induced by a high dose of taxol (Pourmohammadi et al., 2012) and mice (Mo et al., 2012). The effects of lithium on mechanical and thermal allodynia induced by taxol and spinal mechanisms used by lithium remain unknown.

In this study, we found that lithium prevents and attenuates allodynia induced by taxol at least in part through regulating GSK3β signaling, suppression of glial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines, and improved protein expression of glial glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) in the spinal dorsal horn.

Methods and materials

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (body weight: 140-160 g) were used. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Georgia and were fully compliant with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals.

Drug treatment

Depending on groups, rats were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) on four alternate days (days 1, 3, 5, and 7) with either vehicle or paclitaxel (2.0 mg/kg) in an injection volume of 1 ml. Paclitaxel (Taxol, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 6 mg/ml in Cremophor EL and dehydrated ethanol) was diluted with saline to make up a volume of 1 ml. Vehicle was composed of the same amounts of Cremophor EL and dehydrated ethanol (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) diluted with saline to a volume of 1 ml. Lithium chloride (LiCl, Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in saline. Depending on groups, LiCl at a dosage of 2 mM/kg in a volume of 1 ml or saline (1 ml) was subcutaneously administered daily from day 1 to day 10 for the prevention study, or from day 11 to day 18 for the therapeutic study. The dose of LiCl (2 mM/kg/day, or 84.78 mg/kg/day) was chosen according to previous studies showing that LiCl at a dose between 1 to 3 mM/kg/day applied subcutaneously can effectively inhibit GSK3β activities in the brain and spinal cord (Dill et al., 2008, King et al., 2013). When drug administration was to be given on the same day as behavioral testing, all rats were injected after the behavioral measurements were taken. The experimenter was blind to the type of drugs injected to the animal.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests were conducted in a quiet room with room temperature at 22 °C (Weng et al., 2003, Weng et al., 2006). To test mechanical sensitivity, rats were placed on a wire mesh, loosely restrained under a plexiglass cage (12 × 20 × 15 cm3) and allowed to accommodate for at least 30 min. A series of von Frey monofilaments (bending force from 0.58 to 14.68 g) were tested in ascending order to generate response-frequency functions for each animal. Each von Frey filament was applied 5 times to the mid-plantar area of each hind paw from beneath for about 1 s. The response-frequency [(number of withdrawal responses of both hind paws/10) × 100%] for each von Frey filament was determined. Withdrawal response mechanical threshold was defined as the lowest force filament that evoked a 50% or greater response-frequency. This value was later averaged across all animals in each group to yield the group response threshold. To determine changes of thermal sensitivity in the animals, rats were placed on a smooth glass plate pre-set at a temperature of 30 °C, loosely constrained below a cage as described above, and allowed to accommodate for 30 min. A radiant heat beam (diameter 5 mm2) was directed onto the mid-plantar surface of the hind paw from beneath (Hargreaves et al., 1988). Once the paw was withdrawn, the heat beam was turned off automatically by a photocell feedback sensor and the time between the onset and offset of radiant beam was recorded. Three measurements on each hind paw were collected with at least 3 min interval between stimuli and mean withdrawal latency of each rat was determined.

Western blotting

Animals were deeply anesthetized with urethane (1.3–1.5g/kg, i.p.). The L4–L5 spinal segment was exposed by surgery and removed from the rats. The dorsal half of the spinal segment was isolated and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for later use. Frozen tissues were homogenized with a hand-held pellet in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% deoxycholic acid, 2 mM orthovanadate, 100 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μM leupeptin, 100 IU ml−1 aprotinin) for 0.5 hr at 37°C. The samples were then centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 g at 4 °C and the supernatants containing proteins were collected. The quantification of protein contents was made by the BCA method. Protein samples (40 μg) were electrophoresed in 10 % SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk or 5% BSA, then incubated respectively overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal guinea pig anti-GLT-1 (1:1000, EMD Millipore Corporation, MA, USA), monoclonal rabbit anti-IL-1β (1:500, EMD Millipore Corporation, MA, US), monoclonal rabbit anti-phospho or total AKT (1:500), anti-phospho or total mTOR (1:1000), anti-phospho or total GSK3β (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) primary antibodies, or a monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) primary antibody as a loading control. Then the blots were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), visualized in ECL solution (Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) for 1 min, and exposed onto FluorChem HD2 System. The intensity of immunoreactive bands was quantified using ImageJ 1.46 software (NIH). Levels of each biomarker were expressed as the ratio to the loading control protein (β-actin).

Data analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.E. Student's t-test was used to determine the statistical differences between data obtained within the same group (paired t-test) or between groups (non-paired t-test). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

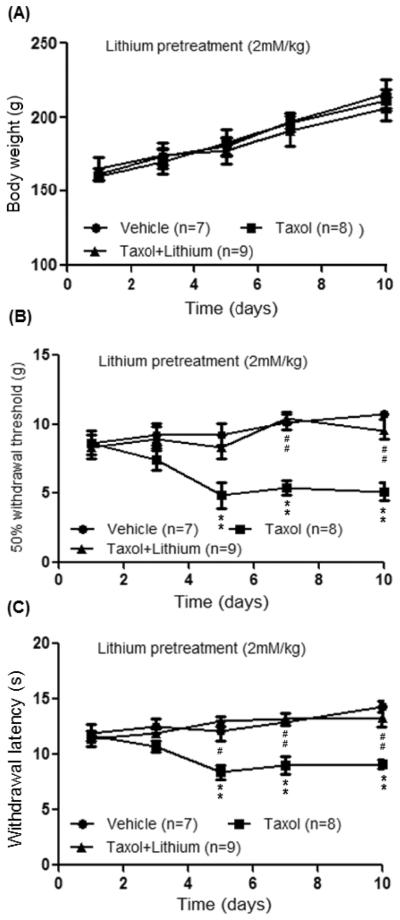

Lithium pre-emptive treatment prevents neuropathic pain induced by taxol

To determine whether lithium can prevent the taxol induced neuropathic pain, rats were randomly assigned into 3 groups: taxol plus lithium group, taxol group, and vehicle group. The taxol plus lithium group received taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) on 4 alternative days plus lithium treatment. Lithium chloride (LiCl, 2 mM/kg, in a volume of 1 ml saline) was subcutaneously injected into the back of the rat immediately before the first i.p. injection of taxol and then daily up to day 10 after the first taxol injection. The taxol group received taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) on 4 alternative days. The vehicle group received vehicle i.p. injection on 4 alternative days. Both the taxol and vehicle groups also received subcutaneous saline (1 ml) injection into the back in the same fashion as that for LiCl. Rats treated with paclitaxel alone or paclitaxel plus lithium showed a gain of body weight similar to that in the vehicle group over the observatory period (Fig. 1), suggesting that neither paclitaxel nor lithium at the current doses significantly alters the general conditions in the animals. Hind paw withdrawal responses to mechanical (von Frey monofilaments) and thermal stimuli (radiant heat) were determined at baseline (day 1) and on days 3, 5, 7, and 10 after the first taxol injection. As shown in Fig. 1, baseline withdrawal response mechanical thresholds and latencies to radiant heat across the three groups were similar. Withdrawal response mechanical thresholds and latencies to radiant heat stimuli in the vehicle group remained constant during the 10 day observatory period. In contrast, 5 days after the first taxol injection, mechanical thresholds of withdrawal responses in the taxol group were significantly reduced (n=8, p<0.01) from 8.66 ± 0.71 g at baseline to 4.86 ± 0.75 g, which were also significantly different from the vehicle group (n=7, p<0.01). Similarly, latencies of withdrawal responses to radiant heat in the taxol group were significantly reduced (n=8, p<0.01) from 11.69 ± 0.47 s at baseline to 8.38 ± 0.62 s on day 5 after the first taxol injection, which were also significantly different from the vehicle group (n=7, p<0.01). These significant differences lasted up to day 10 after the first taxol injection. These data indicate that rats treated with taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) on 4 alternative days develop long lasting mechanical and thermal allodynia, which is consistent with previous results reported by us (Weng et al., 2005) and others (Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012). As seen in Fig. 1, pre-treatment of lithium in taxol treated rats essentially prevented the development of mechanical allodynia and thermal allodynia induced by taxol treatment.

Figure 1.

Lithium pre-emptive treatment prevents neuropathic pain induced by taxol. (A) shows measurements of body weights in all the three groups of rats during the observatory period. Day 1 indicates the baseline measurement before animals received any treatments. (B) and (C) show summaries of the data from the behavioral studies during the observatory period. The taxol plus lithium group received taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) on 4 alternative days plus lithium treatment. Lithium chloride (LiCl, 2 mM/kg, in a volume of 1 ml saline) was subcutaneously injected into the back of the rat immediately before the first i.p. injection of taxol and then daily up to day 10 after the first taxol injection. The taxol group received taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) on 4 alternative days. The vehicle group received vehicle i.p. injection on 4 alternative days. Both the taxol and vehicle groups also received subcutaneous saline (1 ml) injection into the back in the same fashion as that for LiCl. The upper graph shows the mean mechanical thresholds of 50% withdrawal responses in the vehicle group, taxol-group and taxol plus lithium group. The lower graph shows the mean latencies of withdrawal responses to radiant heat stimuli in the same three groups. * comparison between the taxol group and vehicle group; # comparison between the taxol group and taxol plus lithium group. Two symbols: p<0.01.

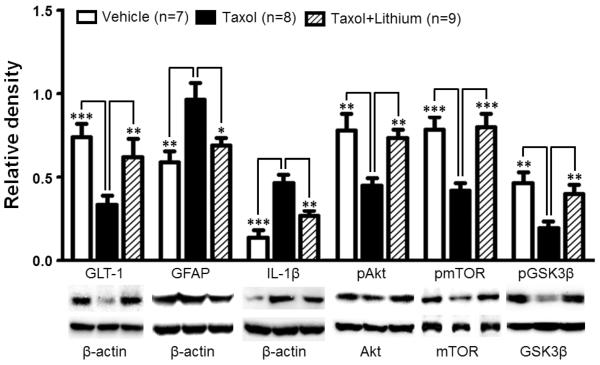

Lithium prevents the taxol induced neuropathic pain through preserving GLT-1 function, suppressing astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn

To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which lithium prevents the development of mechanical and thermal allodynia, biomarkers in the spinal dorsal horns of rats following the completion of the behavioral tests on day 10 were further analyzed using Western blots. Elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012) and deficiency of glial glutamate transporters in the spinal dorsal horn are crucial mechanisms leading to neuropathic pain induced by nerve injury (Sung et al., 2003, Nie and Weng, 2010, Nie et al., 2010) and taxol treatment (Weng et al., 2005, Doyle et al., 2012). We next analyzed protein expression of IL-1β and GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn. We found that in comparison with the vehicle treated group protein expression of IL-1β was significantly increased by 220.17 ± 24.06% (n=8, p<0.001) 10 days after the first taxol injection while protein expression of GLT-1 was significantly reduced by 54.80 ± 7.31% (n=8, p<0.001) (Fig. 2). At the same time, expression of the astrocyte marker GFAP was also significantly increased by 63.45 ± 16.82% (n=8, p<0.01), indicating activation of astrocytes in the spinal dorsal horn. These data confirm the notion made by us and others that reduction of GLT-1 expression (Weng et al., 2005, Doyle et al., 2012), activation of astrocytes, and increased production of IL-1β (Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012) in the spinal dorsal horn contribute to the genesis of neuropathic pain induced by taxol. Pre-emptive treatment of lithium for 10 days prevented the increased production of IL-1β and expression of GFAP, and the decreased GLT-1 expression in the spinal dorsal horn in taxol treated rats (Fig. 2). These data indicate that suppression of astrocytic activation and overproduction of IL-1β, as well as preservation of GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn contribute to molecular mechanisms by which lithium prevents the genesis of the taxol induced neuropathic pain.

Figure 2.

Taxol treatment increases protein expressions of GFAP, IL-1b, and decreases protein expression of GLT-1, ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, p-AKT/t-AKT, and p-mTOR/t-mTOR in the spinal dorsal horn. These changes are prevented by 10 day pre-emptive lithium treatment. Samples of each molecule expression in the spinal dorsal horn obtained on day 10 in the taxol group, taxol plus lithium group and vehicle group are shown. Bar graphs show the mean (+SE) relative density of GFAP, IL-1β and GLT-1 to β-actin, as well as ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, p-AKT/t-AKT, and p-mTOR/t-mTOR in each group. ** p< 0.01; *** p< 0.001.

Lithium prevents the increased GSK3β activities induced by taxol in the spinal dorsal horn

To determine whether GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn mediates the effects induced by lithium treatment, we analyzed protein expressions of GSK3β phosphorylated at the serine 9 residue (p-GSK3β, the inactive form of GSK3β) and total GSK3β (t-GSK3β) in the spinal dorsal horn of rats following the completion of behavioral tests. We found that while protein levels of t-GSK3β (1.71± 0.06, n=8) in the taxol group were similar to those in the vehicle group (1.64 ± 0.12, n=7), ratios of p-GSK3β protein expression over t-GSK3β protein expression in rats receiving taxol (0.19 ± 0.04, n=8) on 10 days after the first injection of taxol were significantly (p<0.01) lower than that in the vehicle group (0.47 ± 0.06, n=7). The reduced expression of p-GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn of the taxol group was prevented by the pre-emptive treatment of lithium (a GSK3β inhibitor) (Beurel et al., 2010) (Fig. 2), while expression of the t-GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn of the taxol group was not significantly altered (n=8, data not shown). These data indicate that increased GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn contribute to the development of taxol-induced behavioral hypersensitivity, and lithium prevents the development of taxol-induced neuropathic pain by suppressing GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn.

Lithium prevents the taxol induced reduction of AKT and mTOR activities

It has been widely recognized that a major upstream signaling molecule regulating GSK3β activities is AKT (also called protein kinase B) (Beurel et al., 2010). Increased phosphorylation of AKT (increased AKT activities) causes phosphorylation of GSK3β (suppression of GSK3β activities) at the serine 9 residue while reduced phosphorylation of AKT (reduced AKT activities) decreases levels of phosphorylation of GSK3β (increased GSK3β activities) (Beurel et al., 2010). Another important substrate of AKT is mTOR. Decreased phosphorylation of AKT reduces phosphorylation of mTOR (decreased mTOR activities) (Vadlakonda et al., 2013). Since p-GSK3β was reduced in taxol-induced neuropathic rats, we conjectured that phosphorylation levels of AKT and mTOR should be reduced at the same time points. Hence, we next analyzed activities of AKT and mTOR in taxol treated rats and their responses to lithium treatment 10 days after the first injection of taxol. We found that ratios of phosphorylated AKT protein (p-AKT) expression over total AKT protein (t-AKT) expression in the spinal dorsal horn were significantly reduced in the taxol group (n=8, p<0.01) (Fig. 2) compared to the vehicle group (n=7). t-AKT protein expression in the taxol group (0.96 ± 0.08, n=8) was similar to that in the vehicle group (0.86 ± 0.04, n=7). The reduced levels of p-AKT (i.e., reduced AKT activities) are consistent with and support our aforementioned findings that GSK3β activities are increased in taxol treated rats. The suppressed AKT activities in the taxol treated rats are further substantiated by the fact that ratios of phosphorylated mTOR protein (p-mTOR) expression over total mTOR protein (t-mTOR) expression measured 10 days after taxol injection were significantly reduced (n=8, p<0.001) (Fig. 2) without changes in t-mTOR (taxol group: 0.78 ± 0.03, n=8; vehicle group: 0.80 ± 0.06, n=7). The changes of ratios of p-AKT/t-AKT and p-mTOR/t-mTOR induced by taxol were normalized by lithium as shown in Figure 2 where p-AKT/t-AKT and p-mTOR/t-mTOR in the taxol plus lithium group were similar to their counterparts in the vehicle group. Lithium treatment did not significantly alter total protein expressions of AKT and mTOR (n=8, data not shown). Together, these data indicate that suppression of the AKT signaling pathway contributes the development of taxol induced neuropathic pain, and these changes are prevented by lithium treatment.

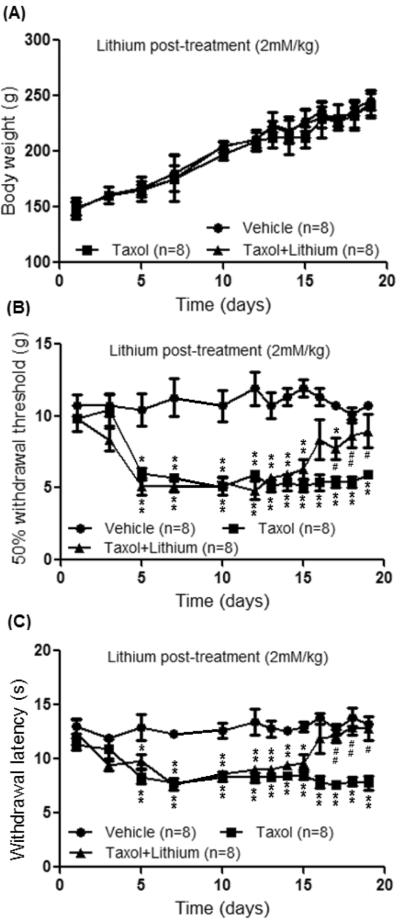

Lithium treatment ameliorates neuropathic pain induced by taxol

To determine whether lithium can attenuate pre-existing neuropathic pain induced by taxol, three groups of rats were used: taxol plus lithium group, taxol group, and vehicle group. Taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) was given to the taxol plus lithium group and the taxol group on 4 alternative days. The vehicle group received vehicle treatment on the same time schedule. On day 11 after the first taxol injection in the taxol plus lithium group, lithium chloride (LiCl, 2 mM/kg, in a volume of 1 ml saline) was subcutaneously injected into the back of the rat and then daily for 8 days. Daily subcutaneous saline injection (1 ml) was given to the taxol group and the vehicle group for 8 days starting from day 11. Body weight gains in all the three groups during the observatory period were similar (Fig. 3). Behavior tests were performed daily 24 hrs after the last subcutaneous injection of lithium or saline. As shown in Fig. 3, prior to lithium or saline treatment (day 10 after the first taxol injection), withdrawal response mechanical thresholds and latencies to radiant heat stimuli in both the taxol plus lithium group (n=8 rats) and taxol group (n=8 rats) were significantly (p<0.01) less than their counterparts at baseline in the same groups or the vehicle group, indicating clear signs of mechanical and thermal allodynia. Rats of the taxol group treated with subcutaneous injection of saline continued to exhibit mechanical and thermal allodynia throughout the remaining observatory period (day 19 after the first taxol injection) (Fig. 3). During the same period, mechanical thresholds and latencies of withdrawal responses obtained from the vehicle group remained stable (Fig. 3). In the taxol plus lithium group, after receiving 6 days of lithium treatment, mechanical thresholds (n=8, p<0.05) and latencies of withdrawal response to radiant heat stimuli were significantly (n=8, p<0.01) increased in comparison with those from the taxol group (n=8) at the same time point (day 17 after the first taxol injection) (Fig. 3). These effects lasted throughout the remaining observatory period (day 19 after the first taxol injection) (Fig. 3). These data indicate that lithium treatment effectively attenuates the pre-existing neuropathic pain induced by taxol.

Figure 3.

Lithium treatment ameliorates neuropathic pain induced by taxol. (A) shows measurements of body weights in all the three groups of rats during the observatory period. (B) and (C) show summaries of the data from the behavioral studies during the observatory period. Taxol (2mg/kg, i.p.) was given to the taxol plus lithium group and the taxol group on 4 alternative days. The vehicle group received vehicle treatment on the same time schedule. On day 11 after the first taxol injection in the taxol plus lithium group, lithium chloride (LiCl, 2 mM/kg, in a volume of 1 ml saline) was subcutaneously injected into the back of the rat and then daily for 8 days. Daily subcutaneous saline injection (1 ml) was given to the taxol group and the vehicle group for 8 days starting from day 11. The upper graph shows the mean mechanical thresholds of 50% withdrawal responses in the vehicle group, taxol-group and taxol plus lithium group. The lower graph shows the mean latencies of withdrawal responses to radiant heat stimuli in the same three groups. * comparison between the taxol group and vehicle group; + comparison between the taxol group plus lithium group and vehicle group; # comparison between the taxol group and taxol plus lithium group. One symbols: p<0.05; Two symbols: p<0.01.

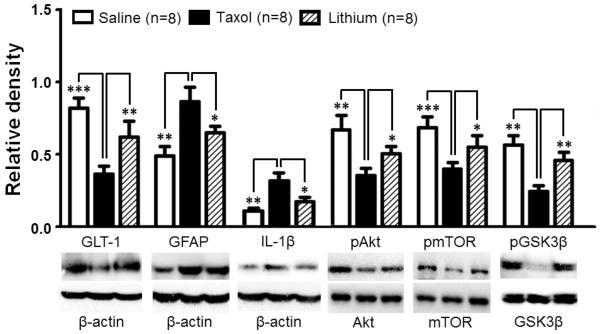

Lithium treatment inhibits astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β, and ameliorates the reduced protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn induced by taxol treatment

After completed behavior tests on day 19, all the three groups of rats were used for Western blot experiments. We found that in comparison with the vehicle group (n=8), the spinal dorsal horn of the taxol treated group (n=8) exhibited a significant (p<0.01) increased protein expression of IL-1β by 189.85 ± 47.50% and a significant reduction of protein expression of GLT-1 by 63.63 ± 5.81% on day 19 after the first taxol injection (Fig. 4). Concurrently, protein expression of the astrocyte marker GFAP in the spinal dorsal horn of the taxol treated group was also significantly increased in the taxol treated group (Fig. 4), indicating activation of astrocytes. These changes were similar to those found on day 10 after the first taxol injection (Fig. 2). These data suggest that astrocytic activation, over-production of IL-1β, and suppressed protein expression of GLT-1 also contribute to the mechanical and thermal allodynia induced by taxol treatment in the later stage. In the taxol plus lithium group, 8 day treatment of lithium (starting on day 11) reversed the changes in expressions of GFAP, IL-1β, and GLT-1 induced by taxol (Fig. 4). These data indicate that suppression of activation of astrocytes and over-production of IL-1β, as well as increase of GLT-1 protein expression contribute to the attenuation of taxol-induced neuropathic pain induced by lithium.

Figure 4.

Lithium treatment inhibits astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β, and ameliorates the reduction induced by taxol treatment in GLT-1 protein expression, ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, p-AKT/t-AKT, and p-mTOR/t-mTOR of in the spinal dorsal horn. Lithium (2 mM/kg/day) was subcutaneously administered on days 11 to 18 in the taxol plus lithium group. Samples of each molecule expression in the spinal dorsal horn obtained on day 19 in the taxol group, taxol plus lithium group and vehicle group are shown. Bar graphs show the mean (+SE) relative density of GFAP, IL-1β and GLT-1 to β-actin, as well as ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, p-AKT/t-AKT, and p-mTOR/t-mTOR in each group. * p< 0.05; ** p< 0.01; *** p< 0.001.

Lithium treatment suppresses the increased GSK3β activities induced by taxol in the spinal dorsal horn

On day 19 after the first taxol injection, protein levels of t-GSK3β (1.18 ± 0.07), t-AKT (0.72 ± 0.03), and t-mTOR (0.62 ± 0.04) in the spinal dorsal horn of the taxol (n=8) group were not significantly different from protein expressions of t-GSK3β (1.27 ± 0.08), t-AKT (0.79 ± 0.05), and t-mTOR (0.68 ± 0.03) of the vehicle group (n=8). At the same time, ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, p-AKT/t-AKT, and p-mTOR/t-mTOR in the taxol group were significantly lower than their counterparts in the vehicle group (Fig. 4). The low levels of phosphorylated GSK3β, AKT and mTOR were significantly improved by 8 day treatment of lithium shown in the taxol plus lithium group (Fig. 4). Lithium treatment did not significantly alter total protein expressions of GSK3β, AKT, and mTOR (n=8, data not shown). These data indicate that suppressed AKT signaling and increased GSK3β activities contribute to the maintenance of taxol-induced allodynia at the later stage, and lithium attenuates taxol-induced neuropathic pain by suppressing GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn.

Discussion

In this study, a central mechanism by which lithium prevents and attenuates the taxol-induced neuropathic pain was revealed for the first time. Specifically, we uncovered that an increased activation of GSK3β (reduced phosphorylation of GSK3β) in the spinal dorsal horn was associated with the development and maintenance of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. These changes of GSK3β activities were supported by the concurrently decreased AKT and mTOR activities. At the same time, protein levels of GFAP and IL-1β were increased while GLT-1 protein expression was reduced. We found that the changes of all these biomarkers were basically prevented when animals received pre-emptive lithium treatment, which also prevented the development of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. Further, chronic lithium treatment, which began on day 11 after the first taxol injection, reversed the pre-existing allodynia induced by taxol. The taxol-induced increased GSK3β activities and decreased AKT and mTOR activities in the spinal dorsal horn were also reversed by lithium treatment. Meanwhile, expressions of GFAP, IL-1β and GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn were improved. Our study is the first to demonstrate that suppression of spinal GSK3β activities is a key mechanism used by lithium to reduce taxol-induced neuropathic pain, and suppression of spinal GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn in taxol treated rats is an effective approach to ameliorate GLT-1 protein expression and suppress activation of astrocytes and IL-1β over-production in the spinal dorsal horn.

Regulation of glial activation and production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn by GSK3β in rats with taxol induced neuropathic pain

Accumulating studies demonstrate that both peripheral and spinal mechanisms play important roles in the genesis of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. For example, treatment of taxol induces a loss of intraepidermal nerve fiber (Boyette-Davis et al., 2011), dysfunctional mitochondria in peripheral nerve axons (Flatters and Bennett, 2006, Jin et al., 2008), and increased expression of TRPV1 in dorsal root ganglion neurons (Hara et al., 2013). In the spinal dorsal horn of rats with taxol-induced neuropathic pain, we found that there are increased spontaneous activities and prolonged afferent evoked after-discharges in the dorsal horn wide dynamic range neurons (Cata et al., 2006a). Activation of microglia (Bianco et al., 2012, Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012, Pevida et al., 2013, Ruiz-Medina et al., 2013) and astrocytes (Bianco et al., 2012, Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012, Pevida et al., 2013, Ruiz-Medina et al., 2013) in the spinal dorsal horn have been shown in rodents receiving repeated taxol treatment by many studies except for one study (Zheng et al., 2011). Over-production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn was observed on days 4 (Burgos et al., 2012) and 15 (Doyle et al., 2012) but not on day 29 (Burgos et al., 2012) after the first taxol injection. Our study confirms and extends these findings by demonstrating increased protein expressions of GFAP (activation of astrocytes) and IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn on days 10 and 20 after first taxol injection. IL-1β is a prototypical pro-inflammatory cytokine known to be critically implicated in the genesis of pathological pain. For example, treatment with antagonists of IL-1β (Sommer et al., 1999, Milligan and Watkins, 2009) or knocking out IL-1β receptors (Wolf et al., 2006, Kleibeuker et al., 2008) in rodents reduces behavioral hypersensitivity induced by nerve injury. We recently demonstrated that endogenous IL-1β in neuropathic rats enhances non-NMDA glutamate receptor activities in postsynaptic neurons, and glutamate release from the primary afferents through coupling with presynaptic NMDA receptors in the spinal dorsal horn (Yan, 2012). Suppression of glial activation with minocycline (Cata et al., 2008) or ibudilast (Ledeboer et al., 2006), or suppression of peroxynitrite (Doyle et al., 2012) attenuates neuropathic pain induced by taxol. In line with these findings, our present study shows that the prevention and amelioration by lithium of taxol-induced mechanical and thermal allodynia are associated with suppression of astrocytic activation and IL-1β production. All these data indicate that glial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines play a critical role in the genesis of taxol-induced neuropathic pain. However, endogenous molecules regulating glial activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines remain unclear. Identifying such molecules would provide strategies for the development of novel analgesics for the treatment of taxol-induced neuropathic pain.

GSK3β is one of molecules recognized in recent years that regulates glial activation and neuroinflammation in the CNS (Beurel and Jope, 2009, Green and Nolan, 2012) and plays a key role in neuroinflammatory processes in many neurological diseases. GSK3β activities in astrocytes and microglia promote the production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα) (Yuskaitis and Jope, 2009, Green and Nolan, 2012) and nitric oxide (Huang et al., 2009, Yuskaitis and Jope, 2009), as well as suppress production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Huang et al., 2009). Inhibition of GSK3β with lithium suppresses demyelination, microglia activation, and leukocyte infiltration in the spinal cord in a mice model of multiple sclerosis (De Sarno et al., 2008). GSK3β is hyperactive in an Alzheimer’s disease mice model (Avrahami et al., 2013). Inhibition of GSK3β activities reduces β-amyloid deposits and ameliorates cognitive deficits, which are associated with the restoration of mTOR activities (Avrahami et al., 2013). Activities of GSK3β are also involved in spinal nociceptive sensory processing. Intraperitoneal injection of GSK3β inhibitors attenuates spinal IL-1β production and allodynia in mice with partial sciatic nerve ligation (Mazzardo-Martins et al., 2012). Second phase formalin nociceptive responses in mice is suppressed by inhibiting GSK3β activities (Martins et al., 2011). Activation of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn is ascribed to regulating NMDA receptor subunits (NR1 and NR2B) trafficking in the spinal cord in an animal model of post-operative hyperalgesia induced by remifentanil (Yuan et al., 2013). Acute i.t. injection of the GSK3β inhibitor restores the analgesic effect of morphine in morphine-tolerant rats (Parkitna et al., 2006). Currently, the role of GSK3β in glial activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn induced by taxol treatment is unknown. In the present study, we found that activities of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn were increased on days 10 and 20 after the first taxol injection in rats with mechanical and thermal allodynia. The increase of GSK3β activities was supported by the fact that AKT and mTOR activities in the same region and time point were reduced. We further demonstrate that suppression of GSK3β activities with lithium prevents and reverses both mechanical and thermal allodynia induced by taxol treatment. These were accompanied with suppression of astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β. Based on these findings, we conclude that GSK3β is a key molecule regulating astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn, as well as the development and maintenance of mechanical and thermal allodynia induced by taxol treatment. In addition to IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6 levels in the spinal dorsal horn are also increased in rats treated with taxol (Burgos et al., 2012, Doyle et al., 2012), further studies are warranted to examine the regulation of these pro-inflammatory cytokines by GSK3β.

Role of GLT-1 in spinal nociceptive sensory processing and its regulation by GSK3β in taxol induced neuropathic pain

It was reported by us and others that dysfunctional glial glutamate transporters in the spinal dorsal horn contribute importantly to behavioral hypersensitivity in rats with pathological pain. Excessive activation of glutamate receptors in spinal dorsal horn neurons is a hallmark mechanism of pathological pain (Ren and Dubner, 2008, Milligan and Watkins, 2009). Since glutamate is not metabolized extracellularly, the clearance of glutamate released from presynaptic terminals and maintenance of glutamate homeostasis depend on glutamate transporters that up-take glutamate into the cell (Danbolt, 2001). Glial glutamate transporters account for over 90% of all CNS synaptic glutamate uptake (Tanaka et al., 1997). It is believed that GLT-1 is a major glial glutamate transporter in the CNS (Tanaka et al., 1997, Danbolt, 2001). We and others have demonstrated that downregulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn is associated with neuropathic pain induced by repeated treatments of taxol (Weng et al., 2005, Doyle et al., 2012) or nerve injury (Sung et al., 2003, Nie and Weng, 2010, Nie et al., 2010). Pharmacological inhibition of spinal glial glutamate transporters induces mechanical and thermal allodynia (Liaw et al., 2005, Weng et al., 2006). At the synaptic level, we demonstrate that deficient glial glutamate uptake enhances activation of AMPA and NMDA receptors, and causes glutamate to spill to extrasynaptic space and activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in spinal sensory neurons (Weng et al., 2007, Nie and Weng, 2009, 2010). Furthermore, we also show that deficiency of glial glutamate uptake in the spinal dorsal horn results in a decrease in GABAergic synaptic activities due to impairment in GABA synthesis through the glutamate-glutamine cycle (Jiang et al., 2012). Only a handful of studies have investigated mechanisms leading to dysfunction of spinal glial glutamate transporter function in the spinal dorsal horn. Glutamate transporter activities are decreased by increased arachidonic acid in nerve-injury induced neuropathic rats (Sung et al., 2007). Studies in cell cultures (Susarla and Robinson, 2008, Garcia-Tardon et al., 2012) and morphine tolerance animals (Tai et al., 2007) indicate that trafficking of glial glutamate transporters between the cell surface and cytosol is a key post-translational mechanism regulating glial glutamate transporter function. In taxol-induced neuropathic rats, nitration of glial glutamate transporters by peroxynitrite reduces glial glutamate transporter function (Doyle et al., 2012). Our study advances this research area by revealing that GSK3β is a key molecule regulating protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn in taxol-induced neuropathic pain. This is in agreement with a previous study in astrocyte cultures showing that increased activities of AKT (an upstream molecule to GSK3β) enhances protein expression of GLT-1 through transcriptional regulation (Li et al., 2006).

Mechanisms by which lithium exerts its analgesic effects

In addition to its well-known mood stabilizing effect (Freland and Beaulieu, 2012, Chiu et al., 2013), lithium has been shown to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain in several animal studies. Systemic administration (intraperitoneal injection) or spinal topical application (intrathecal injection) of lithium effectively reduces thermal and mechanical allodynia induced by chronic constrictive injury (Shimizu et al., 2000) or partial ligation of the sciatic nerve (Banafshe et al., 2012). Hypoalgesia and axonal demyelination in the peripheral nerve induced by a high dose of taxol [accumulated dose: 32 mg/kg in rats (Pourmohammadi et al., 2012) and 18 mg/kg in mice (Mo et al., 2012)] are partially prevented when systemic administration of lithium is pre-emptively administered to the rodents. It was suggested that lithium attenuates neuropathic pain in chronic constrictive injury rats through suppressing the spinal intracellular phosphatidylinositol second messenger system (Shimizu et al., 2000). In taxol-induced neuropathic mice, lithium prevents peripheral neuropathy by preserving the intracellular calcium signaling in the peripheral nerve, a mechanism not related to the alteration of GSK3β activities in the dorsal root ganglion (Mo et al., 2012). It remains unclear whether lithium has analgesic effects on taxol-induced allodynia and its underlying mechanisms. Our study is the first to demonstrate that systemic lithium administration prevents and attenuates taxol induced mechanical and thermal allodynia. These effects are at least in part mediated by increased AKT activities and decreased GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn. These notions are in line with the well-known facts that lithium enhances AKT activities (Chalecka-Franaszek and Chuang, 1999) but reduces GSK3β activities (Beurel et al., 2010, Freland and Beaulieu, 2012), and lithium is effective in the CNS after peripheral administration (Morrison et al., 1971, Ghoshdastidar et al., 1989).

In conclusion, the present study for the first time demonstrates that increased GSK3β activities are involved in activation of astrocytes, over-production of IL-1β, and down-regulation of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn and allodynia in rats treated with taxol. Suppression of GSK3β with lithium is an effective approach to prevent and attenuate taxol-induced neuropathic pain.

Highlights

Increased activation of spinal GSK3β is associated with the genesis of taxol-induced pain.

This is accompanied by increased GFAP, IL-1β expression and a decreased expression of GLT-1.

Lithium (a GSK3β inhibitor) treatment prevents and attenuates taxol-induced neuropathic pain.

Lithium attenuates GSK3β activities, GFAP, IL-1β expression and improves expression of GLT-1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Avrahami L, Farfara D, Shaham-Kol M, Vassar R, Frenkel D, Eldar-Finkelman H. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 ameliorates beta-amyloid pathology and restores lysosomal acidification and mammalian target of rapamycin activity in the Alzheimer disease mouse model: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1295–1306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banafshe HR, Mesdaghinia A, Arani MN, Ramezani MH, Heydari A, Hamidi GA. Lithium attenuates pain-related behavior in a rat model of neuropathic pain: possible involvement of opioid system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Jope RS. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 production is controlled by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and STAT3 in the brain. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) Trends Immunol. 2010;31:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco MR, Cirillo G, Petrosino V, Marcello L, Soleti A, Merizzi G, Cavaliere C, Papa M. Neuropathic pain and reactive gliosis are reversed by dialdehydic compound in neuropathic pain rat models. Neuroscience letters. 2012;530:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyette-Davis J, Xin W, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain. 2011;152:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos E, Gomez-Nicola D, Pascual D, Martin MI, Nieto-Sampedro M, Goicoechea C. Cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 prevents the development of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in rats. Possible involvement of spinal glial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;682:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Chen JH, Dougherty PM. Altered discharges of spinal wide dynamic range neurons and down-regulation of glutamate transporter expression in rats with paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2006a;138:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. Clinical and experimental findings in humans and animals with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Minerva Anes. 2006b;72:151–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. The effects of thalidomide and minocycline on taxol-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Brain research. 2008;1229:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalecka-Franaszek E, Chuang DM. Lithium activates the serine/threonine kinase Akt-1 and suppresses glutamate-induced inhibition of Akt-1 activity in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8745–8750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CT, Wang Z, Hunsberger JG, Chuang DM. Therapeutic potential of mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid: beyond bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:105–142. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P, Axtell RC, Raman C, Roth KA, Alessi DR, Jope RS. Lithium prevents and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J, Wang H, Zhou F, Li S. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 promotes axonal growth and recovery in the CNS. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:8914–8928. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1178-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Cordella JV, Burton A, Weng HR. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain. 2004;109:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Dagostino C, Ryerse J, Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Neumann WL, Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:6149–6160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Pain. 2006;122:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freland L, Beaulieu JM. Inhibition of GSK3 by lithium, from single molecules to signaling networks. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:14. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Tardon N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez IM, Martinez-Villarreal J, Fernandez-Sanchez E, Gimenez C, Zafra F. Protein kinase C (PKC)-promoted endocytosis of glutamate transporter GLT-1 requires ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2-dependent ubiquitination but not phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19177–19187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshdastidar D, Dutta RN, Poddar MK. In vivo distribution of lithium in plasma and brain. Indian J Exp Biol. 1989;27:950–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HF, Nolan YM. GSK-3 mediates the release of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-10 from cortical glia. Neurochemistry International. 2012;61:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Chiba T, Abe K, Makabe A, Ikeno S, Kawakami K, Utsunomiya I, Hama T, Taguchi K. Effect of paclitaxel on transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in rat dorsal root ganglion. Pain. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Lin YS, Wang CY, Tsai CC, Tseng HC, Chen CL, Lu PJ, Chen PS, Qian L, Hong JS, Lin CF. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 negatively regulates anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 for lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS/NO biosynthesis and RANTES production in microglial cells. Immunology. 2009;128:e275–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang E, Yan X, Weng HR. Glial glutamate transporter and glutamine synthetase regulate GABAergic synaptic strength in the spinal dorsal horn. J Neurochem. 2012;121:526–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin HW, Flatters SJ, Xiao WH, Mulhern HL, Bennett GJ. Prevention of paclitaxel-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy by acetyl-L-carnitine: effects on axonal mitochondria, sensory nerve fiber terminal arbors, and cutaneous Langerhans cells. Experimental Neurology. 2008;210:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MK, Pardo M, Cheng Y, Downey K, Jope RS, Beurel E. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors: Rescuers of cognitive impairments. Pharmacol Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleibeuker W, Gabay E, Kavelaars A, Zijlstra J, Wolf G, Ziv N, Yirmiya R, Shavit Y, Tal M, Heijnen CJ. IL-1 beta signaling is required for mechanical allodynia induced by nerve injury and for the ensuing reduction in spinal cord neuronal GRK2. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A, Liu T, Shumilla JA, Mahoney JH, Vijay S, Gross MI, Vargas JA, Sultzbaugh L, Claypool MD, Sanftner LM, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. The glial modulatory drug AV411 attenuates mechanical allodynia in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:279–291. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0700035X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Toan SV, Zelenaia O, Watson DJ, Wolfe JH, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Regulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter expression by Akt: evidence for a selective transcriptional effect on the GLT-1/EAAT2 subtype. J Neurochem. 2006;97:759–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw WJ, Stephens RL, Jr., Binns BC, Chu Y, Sepkuty JP, Johns RA, Rothstein JD, Tao YX. Spinal glutamate uptake is critical for maintaining normal sensory transmission in rat spinal cord. Pain. 2005;115:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins DF, Rosa AO, Gadotti VM, Mazzardo-Martins L, Nascimento FP, Egea J, Lopez MG, Santos AR. The antinociceptive effects of AR-A014418, a selective inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta, in mice. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzardo-Martins L, Martins DF, Stramosk J, Cidral-Filho FJ, Santos AR. Glycogen synthase kinase 3-specific inhibitor AR-A014418 decreases neuropathic pain in mice: evidence for the mechanisms of action. Neuroscience. 2012;226:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan ED, Watkins LR. Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. NatRevNeurosci. 2009;10:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrn2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo M, Erdelyi I, Szigeti-Buck K, Benbow JH, Ehrlich BE. Prevention of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy by lithium pretreatment. Faseb J. 2012;26:4696–4709. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-214643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JM, Jr., Pritchard HD, Braude MC, D'Aguanno W. Plasma and brain lithium levels after lithium carbonate and lithium chloride administration by different routes in rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971;137:889–892. doi: 10.3181/00379727-137-35687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Weng HR. Glutamate transporters prevent excessive activation of NMDA receptors and extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the spinal dorsal horn. Journal of neurophysiology. 2009;101:2041–2051. doi: 10.1152/jn.91138.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Weng HR. Impaired glial glutamate uptake induces extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the spinal sensory synapses of neuropathic rats. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:2570–2580. doi: 10.1152/jn.00013.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Zhang H, Weng HR. Minocycline prevents impaired glial glutamate uptake in the spinal sensory synapses of neuropathic rats. Neuroscience. 2010;170:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkitna JR, Obara I, Wawrzczak-Bargiela A, Makuch W, Przewlocka B, Przewlocki R. Effects of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 inhibitors on morphine-induced analgesia and tolerance in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:832–839. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevida M, Lastra A, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A, Menendez L. Spinal CCL2 and microglial activation are involved in paclitaxel-evoked cold hyperalgesia. Brain Res Bull. 2013;95C:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmohammadi N, Alimoradi H, Mehr SE, Hassanzadeh G, Hadian MR, Sharifzadeh M, Bakhtiarian A, Dehpour AR. Lithium attenuates peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;110:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren K, Dubner R. Neuron-glia crosstalk gets serious: role in pain hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21:570–579. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830edbdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Medina J, Baulies A, Bura SA, Valverde O. Paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain is age dependent and devolves on glial response. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:75–85. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Shibata M, Wakisaka S, Inoue T, Mashimo T, Yoshiya I. Intrathecal lithium reduces neuropathic pain responses in a rat model of peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2000;85:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Petrausch S, Lindenlaub T, Toyka KV. Neutralizing antibodies to interleukin 1-receptor reduce pain associated behavior in mice with experimental neuropathy. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;270:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Sato S, Murayama O, Murayama M, Park JM, Yamaguchi H, Takashima A. Lithium inhibits amyloid secretion in COS7 cells transfected with amyloid precursor protein C100. Neuroscience letters. 2002;321:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B, Lim G, Mao J. Altered expression and uptake activity of spinal glutamate transporters after nerve injury contribute to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2899–2910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02899.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B, Wang S, Zhou B, Lim G, Yang L, Zeng Q, Lim JA, Wang JD, Kang JX, Mao J. Altered spinal arachidonic acid turnover after peripheral nerve injury regulates regional glutamate concentration and neuropathic pain behaviors in rats. Pain. 2007;131:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susarla BT, Robinson MB. Internalization and degradation of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 in response to phorbol ester. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:709–722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C, Leighton IA, Cohen P. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. The Biochemical Journal. 1993;296(Pt 1):15–19. doi: 10.1042/bj2960015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YH, Wang YH, Tsai RY, Wang JJ, Tao PL, Liu TM, Wang YC, Wong CS. Amitriptyline preserves morphine's antinociceptive effect by regulating the glutamate transporter GLAST and GLT-1 trafficking and excitatory amino acids concentration in morphine-tolerant rats. Pain. 2007;129:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Takahashi K, Iwama H, Nishikawa T, Ichihara N, Kikuchi T, Okuyama S, Kawashima N, Hori S, Takimoto M, Wada K. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlakonda L, Dash A, Pasupuleti M, Anil Kumar K, Reddanna P. The Paradox of Akt-mTOR Interactions. Front Oncol. 2013;3:165. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Aravindan N, Cata JP, Chen JH, Shaw AD, Dougherty PM. Spinal glial glutamate transporters downregulate in rats with taxol-induced hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Chen JH, Cata JP. Inhibition of glutamate uptake in the spinal cord induces hyperalgesia and increased responses of spinal dorsal horn neurons to peripheral afferent stimulation. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1351–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Chen JH, Pan ZZ, Nie H. Glial glutamate transporter 1 regulates the spatial and temporal coding of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in spinal lamina II neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;149:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Cordella JV, Dougherty PM. Changes in sensory processing in the spinal dorsal horn accompany vincristine-induced hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain. 2003;103:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G, Gabay E, Tal M, Yirmiya R, Shavit Y. Genetic impairment of interleukin-1 signaling attenuates neuropathic pain, autotomy, and spontaneous ectopic neuronal activity, following nerve injury in mice. Pain. 2006;120:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/Factor A. EMBO Journal. 1990;9:2431–2438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Weng HR. Presynaptic NMDA receptors are used by interleukin-1β to enhance glutamate release from primary afferent terminals in the spinal dorsal horn. 2012 Neuroscience Meeting Planner (Online); New Orleans, LA: Society for Neuroscience; 2012. 2012 Program No. 180.10/II8. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Wang JY, Yuan F, Xie KL, Yu YH, Wang GL. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta contributes to remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia via regulating N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor trafficking. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:473–481. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318274e3f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuskaitis CJ, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates microglial migration, inflammation, and inflammation-induced neurotoxicity. Cell Signal. 2009;21:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng FY, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. The response of spinal microglia to chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies is distinct from that evoked by traumatic nerve injuries. Neuroscience. 2011;176:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]