Abstract

Metalated nitriles are nucleophilic chameleons whose precise identity is determined by the nature of the metal, the solvent, the temperature, and the structure of the nitrile. The review surveys the different structural types and their cyclization trajectories to show how to selectively tune the metalated nitrile geometry for stereoselective cyclizations to a variety of cis or trans hydrindanes, decalins, and bicyclo[4.3.0]undecanes.

Keywords: Nitriles, Cyclizations, Stereoselectivity, Hydrindane, Decalin

1. Introduction

Cyclic metalated nitriles are powerful nucleophiles.[1] Key to the exceptional nucleophilicity is the extremely small steric demand of the CN unit. Compared with carbonyl groups, the compact, cylindrical nature of the C≡N unit (3.6 Å cylindrical diameter of the π-system)[2] results in one of the smallest electron-withdrawing groups. A steric comparison is provided from the respective A-values of carbonyl groups that are typically in excess of 1.0 kcal mol−1 whereas a nitrile group is a mere 0.2 kcal mol−1![3]

The nitrile's minimal steric demand is ideal for alkylations in sterically demanding environments. In fact, alkylations of cyclic metalated nitriles necessarily install a quaternary center, a synthetic feature that has been critical in several natural product syntheses.[4] Typically cyclic metalated nitriles participate in alkylations by positioning the small nitrile in the more sterically congested environment which allows for a more favourable electrophilic trajectory.

Deprotonating cyclic nitriles create powerful nucleophiles.[5] Compared with other electron withdrawing groups, metalated nitriles are up to 100 times more reactive[6] which on occasion allows carbon-carbon bond formations that cannot be achieved with carbonyl analogs.[7] In addition to the small size of the CN unit, the unusual inductive stabilization[8] localizes significant charge density on carbon to create a small, electron rich nucleophile. Synthetically these features relay into a high propensity for C-alkylation of cyclic metalated nitriles. Reactive silyl[9] and acyl[10] chlorides are among the few electrophiles with a propensity for alkylation on nitrogen.

1.1 The Structure of Metalated Nitriles

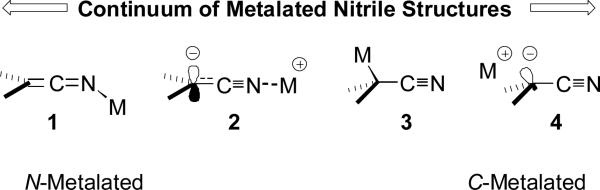

Metalated nitriles are nucleophilic chameleons. Formally regarded as “nitrile anions”, these exceptional nucleophiles exist as a variety of structural types[11] whose precise identity is determined by the nature of the metal, the solvent, the temperature, and the structure of the nitrile. On one extreme are metalated ketenimines 1[12] while on the other end of the continuum are solvent separated nitrile anions 4[8a] (Figure 1). Sandwiched between these extremes are N-metalated nitriles 2 and C-metalated nitriles 3.

Figure 1.

Continuum of metalated nitrile structures.

Although only a few examples exist at the extremes of the continuum, an analysis of their molecular features is very revealing. The best[13] crystallographically characterized metalated ketenimine structure is only favored with a sterically demanding ligand which prevents the palladium from accessing the hindered carbon center.[12] Compared to solid-state structures 2 and 3 the palladated ketenimine is differentiated by a longer C=N bond and a bent C-N-M geometry. These structural features are consistent with sp2 hybridization of a ketenimine nitrogen.

N-Metalated nitriles 2 are the most commonly encountered metalated nitrile because they are readily generated by deprotonating the parent alkanenitrile with a lithium amide base. N-lithiation is favored by the electrophilic lithium which coordinates to the more electron rich nitrile nitrogen.[14] Electron deficient transition metals exhibit a similar preference for N-metalatation in the solid state,[15] particularly with Lewis acidic metals in a high oxidation state.

C-Metalated nitriles are favored by less electropositive transition metals.[16] Platinum, palladium, cobalt, and gold exhibit a pronounced tendency for C-metalation which is only perturbed by strong ligand effects. Of the non-transition metals boron,[17] magnesium,[18] germanium,[19] and zinc[20] adopt C-metalated nitrile structures 3. Coordination of the metal to carbon necessarily generates a tetrahedral nucleophilic carbon with potential for being chiral.

The first evidence for a “chiral nitrile anion” was achieved in pioneering deuterations of cyclopropanecarbonitrile 5 (Scheme 1).[21] Exposing the chiral cyclopropanecarbonitrile 5 to MeONa-MeOD causes greater than 99.9% stereochemical retention in generating 7,[22] presumably through the intermediacy of the transient ion pair 6.[23] Stereochemical retention is favoured by rapid interception of the pyramidal carbanion 6 by proximal, deuterated methanol. In contrast, deprotonating 5 with LDA, which likely generates an N-lithiated nitrile, followed by protonation leads to complete racemization (5→7).

Scheme 1.

Stereochemical integrity of a nitrile anion.

Seminal insight into the structure of metalated nitriles began in the late 1980's as x-ray crystallography of these reactive organometallics identified the position of the metal and provided precise bond distances.[14] Solid state structures show a continuum of geometries for the metalated carbon, ranging from planar through partially pyramidal to tetrahedral (Figure 2, 8,[24] 9,[25], 10[26] respectively). In each case the crystallographic structures exhibit short C-CN bonds (1.36-1.45 Å, Figure 2), consistent with an electrostatic contraction between the formal carbanion and the adjacent electron deficient nitrile.[8] Minimal elongation of the C≡N bond is typical in metalated nitriles, with the bond length (1.15-1.19 Å) being only slightly elongated when compared to the average C≡N bond length in neutral nitriles (1.14 Å).[27] Even in the palladated ketenimine 1 the C=N bond length is only 1.20 Å. The nitrile carbon of metalated nitriles therefore exhibits an apparent preference for a bond order greater than four because of the ylide-type stabilization between the “anionic” and nitrile carbon atoms and the persistence of the C≡N triple bond.

Figure 2.

Partial x-ray structures of metalated nitriles.

1.2 Equilibration Between N- and C-Metalated Nitriles

Solution NMR analysis of metalated nitriles closely correlate the range of structures identified by x-ray crystallography.[28] 6Li-15N NMR coupling in lithiated phenylacetonitrile is consistant with a solution structure essentially identical to that of the solid state structure (cf. 8, Figure 2). Complicating the structural analysis in solution are the presence of monomers and dimers whose precise constituency is strongly influenced by solvation.[28] The dramatic influence of solvation is encapsulated in the complexed lithioacetonitriles 11 and 12 (Figure 3). A fluxional mixture of rapidly equilibrating N- and C-coordinated nitriles is observed in ether at −100 °C whereas only the N-lithiated nitrile 11 is detected in THF (Figure 3).[29]

Figure 3.

Solution structures of metalated nitriles.

Analogous fluxionality between N- and C-ruthenated phenylsulfonylacetonitriles provides seminal insight into the equilibration mechanism (Scheme 2). Kinetic studies with the bis-triphenylphosphane complex 13a indicate an isomerization to 15a by an intermolecular association. Remarkably, the putative dimeric intermediate 14 was isolated and succumbed to characterization by x-ray diffraction.[16a-c,30] When an isonitrile ligand is substituted for one of the triphenylphosphane ligands, the resulting ruthenium complex 13b isomerizes by an intramolecular mechanism! Metal dissociation from 13b and slippage along the π- C-C-N surface of 16 has some parallel in the diversity of coordination modes of cyanide to transition metals.[31]

Scheme 2.

C- to N-Metalated nitrile isomerization mechanisms.

Cyclic metalated nitriles can rapidly equilibrate to one of three different structures; an N-metalated nitrile or two diastereomeric C-metalated nitriles (Scheme 3). Insight into this equilibration was provided by the metalation and alkylation of the bromonitriles 17.[18b] Addition of i-PrMgBr to a −78 °C, THF solution containing methyl cyanoformate and either diastereomeric bromonitrile 17 preferentially affords the same ester nitrile 20 (>12:1). Alkylations of analogous planar ester enolates are less selective,[32] implying that the ester nitrile 20 is generated through a retentive alkylation of 19a. Rapid equilibration to 19a is favoured by positioning the small nitrile group in the less sterically demanding axial orientation and the larger solvated metal in the equatorial orientation. Initial formation of the bromate 18[33] could trigger direct fragmentation to the C-metalated nitrile 19a potentially admixed with the diastereomer 19b, or 18 could fragment to the N-metalated nitrile 19c. Equilibration of 19b to 19a is presumed to occur through 19c by metal migration from carbon to nitrogen and then back again on the opposite face. This “conducted tour equilibration”[34] must be particularly facile[35] because the in situ exchange-alkylation of the individual diastereomeric bromonitriles 17 affords essentially the same acylated nitrile 20.

Scheme 3.

Stereochemical integrity of a nitrile anion.

1.3 Quests for a chiral metalated nitrile

Quests to generate chiral nitrile anions[36] have been complicated by the facile equilibration of metalated nitriles.[34],[37] Seminal configurational analyses of the magnesiated and lithiated nitriles 21 and 22 calculate an inversion barrier of 14 kcal mol-1 for the magnesiated nitrile 21 in diethyl ether at −100 °C.[22] The lithiated nitrile 22 is considerably less stable with rapid racemization only providing an upper limit of 11.1 kcal mol-1 for the inversion barrier.

An alternative strategy for generating chiral, cyclic metalated nitriles is to desymmetrize the carbocyclic ring. Introducing a ring substituent effectively transforms the nucleophilic carbon into a prostereogenic centre for a planar N-metalated nitrile, or into a chiral nucleophilic carbon if C-metalated (Scheme 4). Selective access to the N-metalated nitrile 24a is conceptually possible through judicious metal selection whereas selectively forming 24b over 24c is anticipated on steric grounds. Employing a substituent R bearing a pendant electrophile creates the potential for stereodivergent cyclizations to cis- and trans-fused bicyclic nitriles with the stereochemistry being controlled simply by tuning the geometry of the metalated nitrile.

Scheme 4.

Equilibration route to chiral metalated nitriles.

2. Metalated Nitrile Cyclizations

Metalated nitriles have a rich history in cyclization reactions.[38] Deprotonating cyclic nitriles generates reactive nucleophiles that efficiently alkylate pendant electrophiles to form the ubiquitous hydrindane[39] and decalin scaffolds.[40] A landmark discovery[41] was the metal-dependent stereodivergent cyclization of the ketal-containing nitrile 25 to cis- and trans-decalins 26 and 27, respectively (Scheme 5). The significance lies in the simple means of stereocontrol combined with addressing the challenge[42] in generating decalins that avoid the sometimes troublesome cyclization-equilibration strategies of ketone enolates.

Scheme 5.

Stereodivergent metalated nitrile cyclizations.

2.1 N-Metalated Nitrile Cyclizations

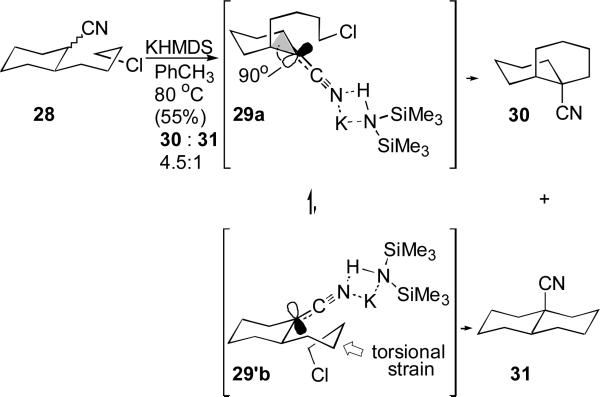

Insight into the stereodivergent cyclizations of metalated nitriles was provided through an extensive series of cyclizations correlating stereoselectivity with solvent, cation, and temperature.[43] The trajectory-based analysis provides insight into the nature of the metalated nitrile by using the diastereomeric product ratio as an indirect probe of the nucleophilic carbon geometry during the alkylation. Cyclizations of the parent carbonitrile 28 under conditions favoring N-metalation, such as KHMDS in toluene, favor the cis-decalin 30 over the trans-decalin 31. The stereoselectivity is consistent with preferential cyclization through the planar N-metalated nitrile conformer 29a (Scheme 6) which avoids the tortional strain imposed by twisting of the electrophilic tether attending cyclization via 29b to the trans-decalin 31.

Scheme 6.

N-Metalated nitrile cyclization to a cis-decalin.

2.2 Nitrile Anion Cyclizations

Cyclizations of the probe nitrile 28 under conditions favoring a nitrile anion revealed fundamental differences compared with cyclizations of the N-metalated nitrile 29. As an immediate point of departure, cyclizing 28 in refluxing THF preferentially affords the trans-decalin 31 (Scheme 7).[43] No significant selectivity change occurs in the presence of 18-C-6, supporting the intermediacy of a solvent separated ion pair. The selectivity is consistent with preferential cyclization of the pyramidal nitrile anion 32a in which the small nitrile adopts the axial orientation with an equatorial nucleophilic anion ideally oriented for an SN2 displacement. Cyclization through the diastereomeric nitrile anion 32b, epimeric at the nitrile-bearing carbon, incurs steric compression between the synaxial protons and the chloromethylene and ring methylene (*) carbons.

Scheme 7.

Nitrile anion cyclization to a trans-decalin.

Comparing the trans-selective cyclization of 28 in refluxing THF (Scheme 7) with the cis-selective cyclization of 28 in toluene (Scheme 6), underscores the importance of the anion geometry in controlling the cyclization stereochemistry. The pyramidal, sp3 hybridized nitrile anion 32a projects toward the electrophile at an angle of 120° relative to the plane containing the adjacent three rings carbons (grey) whereas the nucleophilic p-orbital of the N-metalated nitrile 29 projects at a reduced angle of 90°. The difference in the attack angle changes the tortional strain required for cyclization to the trans-decalin which otherwise benefits by placing the small nitrile in the sterically more demanding axial orientation.

Extending the nitrile anion strategy to the synthesis of trans-hydrindanes is significantly more challenging because trans-hydrindanes, unlike their decalin counterparts,[42a] are typically thermodynamically less-stable than their cis-fused counterparts.[44] Two nitrile anion cyclization strategies are available for generating trans-hydrindanes; cyclizing a 6-membered ring with a 3-carbon electrophilic tether (33→35, Scheme 8), or cyclizing a 5-membered ring bearing a four-carbon electrophilic tether (36→35, Scheme 8).[45] Exploring the nitrile anion cyclization in both series leads only to the cis-hydrindane 35. Presumably the torsional strain for cyclization via the pyramidal, nitrile anion 34a is greater than the steric compression experienced in the diastereomeric anion 34b leading to the cis-hydrindane 35. Relaxing the torsional strain in the tether by increasing the length of the carbon chain, and simultaneously decreasing the ring size as in 37, still affords only the cis-hydrindane 35 (Scheme 8).[46]

Scheme 8.

Nitrile anion cyclizations to a cis-hydrindane.

2.3 Chelated Nitrile Anion Cyclizations

Greater control over the orientation of the anionic orbital is achieved with chelated nitrile anions. The dramatic influence of chelation was demonstrated in the stereodivergent cyclizations of the diastereomeric hydroxynitriles 38 and 41 (Scheme 9).[47] Adding excess LiNEt2 to 38 or 41 first deprotonates the hydroxyl group which prevents subsequent elimination on deprotonation at the adjacent nitrile-bearing carbon.[48] Complexation in the resulting dilithiated nitriles 39 and 42 between the lithium alkoxide[49] and the nitrile π-electrons[50] effectively locks the lithiated nitrile in a pyramidal geometry, the geometry of the chiral carbanion being determined by the configuration of the adjacent alkoxide.[51] For the equatorially oriented hydroxynitrile 38, the chelate 39 with the axial nitrile is favoured which directs the cyclization exclusively to the trans-decalin 40. Cyclization of the axial hydroxynitrile 41 can only proceed through chelate 42 with the nitrile in the equatorial orientation. Chelate 42 has the opposite relative configuration of the chiral carbanion compared to 39 which channels the displacement to the cis-decalin 43.

Scheme 9.

Stereodivergent nitrile anion cyclizations.

The lithium-nitrile interaction is critical for controlling hydroxynitrile cyclizations to cis- and trans-hydrindanes. The combination of lithium-nitrile complexation and greater flexibility in cyclizations to cis-fused carbocycles allows a particularly facile cyclization of 44 (Scheme 10). Deprotonating 44 with excess LiNEt2 may lead to an equilibrium mixture of metalated nitriles 45a and 45b because the respective steric demands are similar. Cyclization from 45a and 45b leads to the same cis-fused hydrindane 46 because chelation effectively positions the nucleophilic orbital and the electrophilic tether on the same side of the cyclohexane ring in each case.

Scheme 10.

cis-selective alkoxide-nitrile anion cyclization.

Cyclizing the diastereomeric β-hydroxynitrile 47 to a trans-hydrindane is significantly more subtle. Deprotonating 47 (Scheme 11) with excess LiNEt2 generates two chelates 48a and 48b having three significant differences; steric, torsional differences in the tether, and torsional differences in the chelate. Although steric compression is minimized in 48a by positioning the small nitrile group in an axial orientation, the cyclization confers considerable twisting in the electrophilic tether. Twisting of the tether is relieved in the alternative chelate 48b but with additional steric strain from the axial methylenes in the developing ring (*) and torsional strain in the chelate. Viewed as a 5-membered chelate, the lithium-nitrile chelate in 48b resides within a trans-hydrindane whereas 48a is contained within a cis-hydrindane. The outcome of these competing effects is formation of approximately equal amounts of trans- and cis- hydrindanes 49 and 50, respectively.

Scheme 11.

Chelate-controlled hydrindane cyclizations.

The dramatic influence of the lithium-nitrile π interaction is starkly illustrated by comparing the cyclization of 47 (Scheme 11) with the analogous des-hydroxynitrile cyclization (Scheme 8). In the absence of chelation 33 cyclizes exclusively to the cis-hydrindane 35 (Scheme 8). Moving the lithium alkoxide one carbon further from the nitrile is thought to reduce the interaction because the dilithiated nitrile 53[52] cyclizes only to the cis-hydrindane 54 (Scheme 12). Deprotonating the γ-hydroxynitrile 51 with BuLi is thought to proceed via an oxygen assisted deprotonation[53] of the alkoxide 52 because alkyllithiums are otherwise prone to attack nitriles.[54] The resulting dilithiated nitrile 53a cyclizes to the cis-hydrindane 54 which suggests that cyclization via the chelated nitrile anion 53a is unfavorable relative to the N- or C-lithiated nitriles 53b or 53c. Presumably the greater distance between the lithium alkoxide and the nitrile in 53a reduces the lithium-nitrile interaction which insufficiently compensates for the torsional strain in the tether. Although tentative, cyclization might occur through the C-lithiated nitrile 53c which is structurally analogous to internally chelated organolithiums.[53]

Scheme 12.

Cyclization of a γ-chelated nitrile anion.

The same preference for a cis-hydrindane persists in the analogous SN2′ displacement of the γ-hydroxynitrile 55 bearing an allylic electrophile (Scheme 13).[52] Addition of excess BuLi to 55 generates two cis-hydrindanes 57 and 58 that correlate with cyclization through internally coordinated C-lithiated nitriles 56 and 56′, respectively. Forming the two cis-hydrindanes 57 and 58 in roughly equal amounts likely reflects similar energetics for the nucleophilic attack on the diastereotopic faces of the allylic chloride.

Scheme 13.

SN2′ cyclization of a γ-chelated nitrile anion.

Preferential cyclization of a chelated nitrile anion to a trans-hydrindane requires positioning the chelate adjacent to the nitrile and cyclizing a pre-existing 5-membered ring onto a 4-carbon tether (Scheme 14). Deprotonating 59 with excess LiNEt2 leads to two pyramidal metalated nitriles in which optimal chelation is achieved with the cis-fused chelate 60a rather than with a less stable trans-fused chelate in 60b. In THF cyclization affords primarily the trans-hydrindane 61 and less of the cis-hydrindane 62. Repeating the cyclization with excess HMPA, to sequester the less-tightly associated Li*, affords only the trans-hydrindane 61, consistent with greater complexation between the remaining lithium and the more electron rich nitrile π-system (see inset 63, Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Chelation-controlled cyclizations to cis- and trans-hydrindanes.

2.4 C-Cuprated Nitrile Cyclizations

Alkylations with C-metalated nitriles are relatively poorly explored. Comparable alkylations of C-metalated nitriles exhibit distinctly different reactivity and stereoselectivity preferences compared to their N-lithiated and anion counterparts.[18a,b] In contrast to lithium, copper and magnesium prefer to coordinate to the carbon atom of metalated nitriles. Forming the C-cuprated nitrile 64 from 28 is readily achieved by sequential deprotonation and addition of MeCu (Scheme 15), employing low temperatures to prevent premature cyclization of the N-lithiated nitrile intermediate (cf. Scheme 6). Exclusive cyclization to the trans-decalin 31 implies formation of an equatorially orientated organocopper 64 which inserts into the proximal C-Cl bond to form the copper(III) intermediate 65.[55] Subsequent reductive elimination with retention of the C-Cu configuration affords the trans-decalin 31. For comparison, cyclizing the nitrile anion derived from 28 affords the trans-decalin 31 and the corresponding cis-decalin in a 6.3:1 ratio (Scheme 7).[43]

Scheme 15.

Cyclization of a C-cuprated nitrile to a trans-decalin.

C-cuprated nitriles are significantly less reactive than their lithiated and magnesiated counterparts. Refluxing the C-cuprated nitrile derived from 33 (Scheme 16) fails to generate any of the hydrindane 35! The cyclization of 66 requires the addition of silver tetrafluoroborate to coax displacement of the pendant electrophile to the cis-hydrindane 35.[45] Exclusive formation of the cis-hydrindane 35 implies cyclization through conformer 66b in which the large methyl copper is axial despite the steric preference for positioning the smaller nitrile in the more sterically demanding axial orientation.[56] Presumably a greater torsional strain in the tether occurs for cyclization from conformer 66a which is relieved in conformer 66b leading to the cis-hydrindane. Relaxing the steric constraints by incorporating an additional carbon in the tether and using a methylene contracted cyclopentane still results in cyclization to a cis-hydrindane (Scheme 16, 36→67→35).

Scheme 16.

C-cuprated nitrile cyclizations to a cis-hydrindane.

2.5 Stereodivergent metal-dependent nitrile cyclizations

Tuning the stereochemistry of metalated nitriles by solvent diverts the cyclization to cis- or trans-decalins (Schemes 6 and 7). Greater selectivity in stereodivergent cyclizations is achieved in the cation-controlled cyclizations of γ-hydroxynitriles.[52] Deprotonating γ-hydroxy nitriles such as 68 (Scheme 17) permits two coordination modes by virtue of a metal's capacity to form one or two formal bonds. Addition of excess i-PrMgCl to the γ-hydroxynitrile 68 triggers sequential deprotonation of the hydroxyl proton and a halogen-alkyl exchange to afford the alkylmagnesium alkoxide 69.[57] Forming the axial alkylmagnesium alkoxide 69 conveniently anchors the basic iso-propyl group for a directed, internal deprotonation leading to the C-magnesiated nitrile 70. Although the side-on orbital overlap between the C-Mg nucleophilic orbital and the σ* C-Cl orbital is far from optimal (70), the alternative co-linear approach of an sp3 hybridized electrophile to the small σ lobe of the C-Mg bond is sterically prohibited. The cyclization through 70 to the cis-decalin 72 is therefore stereoelectronically controlled.

Scheme 17.

Stereodivergent cation-controlled cyclizations.

Deprotonating the same γ-hydroxyalkenenitrile 68 with BuLi generates the diastereomeric trans-decalin 73 consistent with cyclization through the pyramidal nitrile anion 72 (Scheme 17). Internal coordination of the alkoxide lithium with the nitrile π-system generates an equatorially oriented nucleophile within 72 that is ideally positioned for an SN2 displacement through a chair-chair conformation. The monovalent character of the metal therefore directs the cyclization of 72 to the trans-decalin 73 whereas the divalent magnesium counterion in 70 directs cyclization to the cis-decalin 72.

The stereodivergent metal-based cyclization strategy is equally effective for generating cis- and trans-bicyclo[5.4.0]undecanes although cyclizing the 7-membered ring is surprisingly more difficult. i-PrMgCl-induced cyclization of the nitrile 74a (Scheme 18) requires converting the chloride to the corresponding iodide 74b and heating of the reaction to reflux. Essentially no cyclization of the chloride or iodide occurs at room temperature, conditions under which the corresponding decalin is formed (Scheme 17). Cyclization with BuLi is most effective with the chloride 74a but the cyclization requires two days for full conversion. The extended reaction time allows for the first-formed alkoxide to internally attack the proximal axial nitrile leading to the trans-lactone 76 after an aqueous workup.

Scheme 18.

Stereodivergent bicyclo[5.4.0]undecane cyclizations.

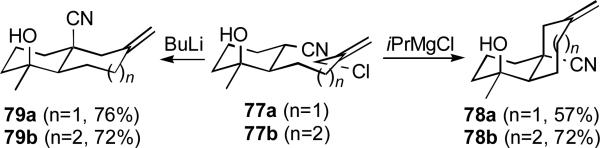

Analogous cyclizations of the γ-hydroxynitriles 77a and 77b bearing allylic electrophiles provide modestly functionalized cis- and trans-decalins and bicyclo[5.4.0]undecanes (Scheme 19). i-MgCl-induced cyclizations of 77a and 77b lead exclusively to the cis-fused decalin 78a and cis-undecane 78b. Standard addition of BuLi to 77a or 77b triggers two facile trans-selective cyclizations to 79a and 79b without lactone formation.

Scheme 19.

Stereodivergent cyclizations of γ-hydroxynitriles bearing allylic electrophiles.

Understanding the intricacies of metalated nitrile cyclizations allows a reinterpretation of the first stereodivergent cation-controlled cyclization (Scheme 20).[41] Although the original argument was based on early and late contact distances, a more compelling rationale is a cation controlled cyclization. The potassium counter ion likely favors cyclization to the cis-decalin 26 through a planar N-metalated nitrile (cf. 29 Scheme 6) whereas the lithium ion complexes with the ketal and the nitrile π electrons to channel cyclization through the pyramidal anion 80. In support of this complexation, the selectivity is reduced in THF which likely better competes as a ligand for the lithium cation.

Scheme 20.

Stereodivergent metalated nitrile cyclizations.

Conclusions

Metalated nitriles are outstanding nucleophiles for cyclization reactions. Judicious choice of solvent, temperature, and cation allows excellent control over the geometry of the nucleophilic nitrile-stabilized carbon (Figure 5). The most common metalated nitriles 82, generated by deprotonating with a lithium amide base, cyclize with a modest preference for cis-fused carbocycles. Better stereoselectivity is possible with the internally coordinated C-magnesiated counterpart 85 which cyclizes exclusively to cis-fused bicyclic nitriles.

Figure 5.

Metalated nitrile cyclization selectivities.

Solvent-separated nitrile anions 83 preferentially cyclize to trans-fused bicyclic nitriles when the tether containing the electrophile has four carbons. Fewer carbons in the electrophilic tether engenders too much strain for cyclization to a trans-hydrindane and favors cyclization to the cis-hydrindane. The difficulty stems from twisting of the tether containing the electrophilic chloromethylene carbon required for the correct SNi alignment. Improved selectivity for the trans-decalin is achieved in cyclizations of the C-metalated nitrile 84. Greatest selectivity for trans-fused bicyclic nitriles is accomplished with dilithiated nitrile anions 85 in which the pyramidal geometry of the nucleophile is defined by precise internal coordination.

Metalated nitrile cyclizations assemble carbocycles with excellent control at the quaternary ring junction carbon. Tuning the metalated nitrile geometry allows facile, stereodivergent syntheses of cis- and trans-hydrindanes, decalins, and bicyclo[4.3.0]undecanes. Collectively, these cyclizations demonstrate the key influence of solvent, metal, and chelation in controlling the geometry at the nucleophilic nitrile-bearing carbon. The facile, stereodivergent metalated nitrile cyclizations are ideal for assembling complex molecular architectures required in natural product synthesis.

Figure 4.

Solution structures of chiral metalated mitriles.

Acknowledgments

Extended support for developing the chemistry of metalated nitriles from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged. Equally as important are the contributions from an outstanding series of coworkers whose names are listed in the individual references.

Biography

Fraser Fleming received his B. Sc. (Hons.) from Massey University, New Zealand, in 1986 and then moved to the University of British Columbia, Canada to pursue a Ph. D. under the direction of Edward Piers. After graduating in 1990 he moved to Oregon State University for postdoctoral research with James D. White and then in 1992 he joined the faculty at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. His research interests lie in developing stereoselective alkylations with metalated nitriles and conjugate additions to unsaturated nitriles.

Fraser Fleming received his B. Sc. (Hons.) from Massey University, New Zealand, in 1986 and then moved to the University of British Columbia, Canada to pursue a Ph. D. under the direction of Edward Piers. After graduating in 1990 he moved to Oregon State University for postdoctoral research with James D. White and then in 1992 he joined the faculty at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. His research interests lie in developing stereoselective alkylations with metalated nitriles and conjugate additions to unsaturated nitriles.

Subrahmanyam Gudipati received his B. Sc. from Osmania University in 1998 and then pursued an M.S. from the University of Hyderabad, India. In 2002 he moved to Duquesne University, USA to pursue an M.S. degree under the direction of Fraser Fleming. After graduating in 2007 he moved to Schering-Plough Research Institute (SPRI), New Jersey, USA as an Assistant Scientist. Currently at SPRI he is pursuing a Ph.D. part-time working on iodine-magnesium exchange chemistry.

Subrahmanyam Gudipati received his B. Sc. from Osmania University in 1998 and then pursued an M.S. from the University of Hyderabad, India. In 2002 he moved to Duquesne University, USA to pursue an M.S. degree under the direction of Fraser Fleming. After graduating in 2007 he moved to Schering-Plough Research Institute (SPRI), New Jersey, USA as an Assistant Scientist. Currently at SPRI he is pursuing a Ph.D. part-time working on iodine-magnesium exchange chemistry.

References

- 1.Fleming FF, Zhiyu Z. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:747. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheppard WA. Rappoport, editor. The Chemistry of the Cyano Group. 1970 Ch. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliel Ernest L., Wilen Samuel. H., Mander Lewis N. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley, NY: 1994. pp. 696–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For strategic alkylations of cyclic nitriles, excluding oxonitriles, in total syntheses see: Hutt OE, Mander LN. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:10130. doi: 10.1021/jo701995u.Mander LN, Thomson RJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:1654. doi: 10.1021/jo048199b.Mander LN, Thomson RJ. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1321. doi: 10.1021/ol0342599.Miyaoka H, Shida H, Yamada N, Mitome H, Yamada N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;43:2227.Rahman SMA, Ohno H, Murata T, Yoshino H, Satoh N, Murakami K, Patra D, Iwata C, Maezaki N, Tanaka T. Org. Lett. 2001;3:619. doi: 10.1021/ol007059v.Rahman SMA, Ohno H, Murata T, Yoshino H, Satoh N, Murakami K, Patra D, Iwata C, Maezaki N, Tanaka T. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:4831. doi: 10.1021/jo015590d.Piers E, Caille S, Chen G. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2483. doi: 10.1021/ol0061541.Piers E, Breau ML, Han Y, Plourde GL, Yeh W-L. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1995:963.Piers E, Wai JSM. Can. J. Chem. 1994;72:146.Kucera DJ, O'Connor SJ, Overman LE. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5304.Piers E, Roberge JY. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6923.Darvesh S, Grant AS, MaGee DI, Valenta Z. Can. J. Chem. 1991;69:712.Darvesh S, Grant AS, MaGee DI, Valenta Z. Can. J. Chem. 1989;67:2237.Ahmad Z, Goswami P, Venkateswaran RV. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:6833.Piers E, Wai JSM. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1988:1245.Piers E, Wai JSM. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1987:1342.Ahmad Z, Goswami P, Venkateswaran RV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4329.

- 5.Watt DS, Arseniyadis S, Kyler KS. Org. React. 1984;31:1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bug T, Mayr H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12980. doi: 10.1021/ja036838e.Benedetti F, Berti F, Fabrissin S, Gianferrara T. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:1518. Comparative alkylations of sterically hindered nitriles, acids, and esters demonstrate the superior nucleophilicity of metallated nitriles: MacPhee J-A, DuBois J-E. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:775.

- 7.Barton DHR, Bringmann G, Motherwell WB. Synthesis. 1980:68. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Bradamante S, Pagani GA. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. II. 1986:1035. [Google Scholar]; b Dayal SK, Ehrenson S, Taft RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:9113. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Kawakami Y, Hisada H, Yamashita Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:5835. [Google Scholar]; b Watt DS. Synth. Commun. 1974;4:127. [Google Scholar]; c Kruger CR, Rochow EG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1963;2:617. [Google Scholar]; d Prober MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:2274. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Fleming FF, Wei G, Zhiyu Z, Steward OW. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4903. doi: 10.1021/ol0619765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Enders D, Kirchhoff J, Gerdes P, Mannes D, Raabe G, Runsink J, Boche G, Marsch M, Ahlbrecht H, Sommer H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998:63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a theoretical analysis of aggregates and transition states for deprotonation see: Koch R, Wiedel B, Anders E. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:2523.

- 12.a Culkin DA, Hartwig JF. Organometallics. 2004;23:3398. [Google Scholar]; b Culkin DA, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9330. doi: 10.1021/ja026584h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For a related dimeric ketenimine structure see: Lee VY, Ranaivonjatovo H, Escudié J, Satgé J, Dubourg A, Declercq J-P, Egorov MP, Nefedov OM. Organometallics. 1998;17:1517.

- 14.Boche G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1989;28:277. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Tanabe Y, Seino H, Ishii Y, Hidai M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1690. [Google Scholar]; b Murahashi S-I, Take K, Naota T, Takaya H. Synlett. 2000:1016. [Google Scholar]; c Triki S, Pala JS, Decoster M, Molinié P, Toupet L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:113. [Google Scholar]; d Hirano M, Takenaka A, Mizuho Y, Hiraoka M, Komiya S. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1999:3209. [Google Scholar]; e Yates ML, Arif AM, Manson JL, Kalm BA, Burkhart BM, Miller JS. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:840. [Google Scholar]; f Jäger L, Tretner C, Hartung H, Biedermann M. Chem. Ber. 1997;130:1007. [Google Scholar]; g Zhao H, Heintz RA, Dunbar KR, Rogers RD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:12844. [Google Scholar]; h Murahashi S-I, Naota T, Taki H, Mizuno M, Takaya H, Komiya S, Mizuho Y, Oyasato N, Hiraoka M, Hirano M, Fukuoka A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:12436. [Google Scholar]; i Hirano M, Ito Y, Hirai M, Fukuoka A, Komiya S. Chem. Lett. 1993:2057. [Google Scholar]; j Mizuho Y, Kasuga N, Komiya S. Chem. Lett. 1991:2127. [Google Scholar]; k Schlodder R, Ibers JA. Inorg. Chem. Soc. 1974;13:2870. [Google Scholar]; l Ricci J, Ibers JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:2391. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a Naota T, Tannna A, Kamuro S, Hieda N, Ogata K, Murahashi S-I, Takaya H. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:2482. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Naota T, Tannna A, Kamuro S, Murahashi S-I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6842. doi: 10.1021/ja017868p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Naota T, Tannna A, Murahashi S-I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2960. [Google Scholar]; d Alburquerque PR, Pinhas AR, Krause Bauer JA. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;298:239. [Google Scholar]; e Ruiz J, Rodríguez V, López G, Casabó J, Molins E, Miravitlles C. Organometallics. 1999;18:1177. [Google Scholar]; f Ragaini F, Porta F, Fumagalli A, Demartin F. Organometallics. 1991;10:3785. [Google Scholar]; g Porta F, Ragaini F, Cenini S, Demartin F. Organometallics. 1990;9:929. [Google Scholar]; h Ko JJ, Bockman TM, Kochi JK. Organometallics. 1990;9:1833. [Google Scholar]; i Cowan RL, Trogler WC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4750. [Google Scholar]; j Chopra SK, Cunningham D, Kavanagh S, McArdle P, Moran G. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1987:2927. [Google Scholar]; k Del Pra A, Forsellini E, Bombieri G, Michelin RA, Ros R. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1979:1862. [Google Scholar]; l Lenarda M, Pahor NB, Calligaris M, Graziani M, Randaccio L. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1978:279. [Google Scholar]; m Schlodder R, Ibers JA, Lenarda M, Graziani M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:6893. [Google Scholar]; n Yarrow DJ, Ibers JA, Lenarda M, Graziani M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1974;70:133. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brauer DJ, Pawelke G. J. Fluorine Chem. 1999;98:143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Fleming FF, Gudipati S, Zhang Z, Liu W, Steward OW. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3845. doi: 10.1021/jo0501184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fleming FF, Zhang Z, Liu W, Knochel P. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:2200. doi: 10.1021/jo047877r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Thibonnet J, Vu VA, Knochel P. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:4787. [Google Scholar]; d Thibonnet J, Knochel P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:3319. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller KA, Watson TW, Bender IV JE, Holl MMB, Kamp JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:982. doi: 10.1021/ja0026408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a Brombacher H, Vahrekamp H. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:6054. doi: 10.1021/ic049177a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Orsini F. Synthesis. 1985:500. [Google Scholar]; c Goasdoue N, Gaudema M. J. Organometal. Chem. 1972;39:17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walborsky HM, Motes JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:2445. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlier PR, Zhang Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1319. doi: 10.1021/ol070149g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoz S, Aurbach D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2340. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boche G, Marsch M, Harms K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1986;25:373. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker J, Barnett NDR, Barr D, Clegg W, Mulvey RE, O'Neil PA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1993;32:1366. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boche G, Harms K, Marsch M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:6925. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Questel J-Y, Berthelot M, Laurence C. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2000;13:347. [Google Scholar]

- 28.a Carlier PR, Lucht BL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:11602. [Google Scholar]; b Carlier PR, Lo CW-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;116:12819. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sott R, Granander J, Hilmersson G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6798. doi: 10.1021/ja0388461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.For a related interconversion of palladium complexes see: Kujime M, Hikichi S, Akita M. Organometallics. 2001;20:4049.

- 31.Michelin RA, Mozzon M, Bertani R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996;147:299. [Google Scholar]

- 32.a Krapcho AP, Dundulis EA. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:3236. [Google Scholar]; b House HO, Bare TM. J. Org. Chem. 1968;33:943. [Google Scholar]

- 33.a Hoffmann RW, Brönstrup M, Muller M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:313. doi: 10.1021/ol027307i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schulze V, Brönstrup M, Böhm VPW, Schwerdtfeger P, Schimeczek M, Hoffmann RW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:824. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980403)37:6<824::AID-ANIE824>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Reich HJ, Green DP, Phillips NH, Borst JP, Reich IL. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon. 1992;67:83. [Google Scholar]

- 34.For a computational analysis in lithiated cyclopropanecarbonitrile see: Carlier PR. Chirality. 2003;15:340. doi: 10.1002/chir.10222.

- 35.For a related equilibration see: Reich HJ, Medina MA, Bowe MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:11003.

- 36.Subsequent approaches to chiral metalated nitriles have employed non-covalently linked chiral additives: Suto Y, Kumagai N, Matsunaga S, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3147. doi: 10.1021/ol035206u.Carlier PR, Lam WW-F, Wan NC, Williams ID. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2252::AID-ANIE2252>3.0.CO;2-Z.Kuwano R, Miyazaki H, Ito Y. Chem. Commun. 1998:71.Soai K, Hirose Y, Sakata S. Tetrahedron Asymm. 1992;3:677.Soai K, Mukaiyama T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:3371. For metalated nitriles containing chiral auxiliaries see: Enders D, Shilvock JP, Raabe G. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin I. 1999:1617.Roux M-C, Patel S, Mérienne CG, Wartski. Morgant L. Bull. Chem. Soc. Fr. 1997;134:809.Schrader T. Chem. Eur. J. 1997;3:1273.Enders D, Kirchhoff J, Lausberg V. Liebigs. Ann. 1996:1361.Roux M-C, Wartski L, Nierlich M, Lance M. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:10083.Enders D, Kirchhoff J, Mannes D, Raabe G. Synthesis. 1995:659.Cativiela C, Díaz-de-Villegas MD, Gálvez JA, Lapeña Y. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:5921.Cativiela C, Díaz de Villegas MD, Gálvez JA. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2497. doi: 10.1021/jo051592c.Enders D, Mannes D, Raabe G. Synlett. 1992:837.Enders D, Gerdes P, Kipphardt H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1990;29:179.Hanamoto T, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2463.Marco JL, Royer J, Husson H-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:3567.Enders D, Lotter H, Maigrot N, Mazaleyrat J-P, Welvart Z. Nouv. J. Chem. 1984;8:747.

- 37.Kasatkin AN, Whithy RJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:6201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming FF, Shook BC. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.a Jankowski P, Marczak S, Wicha J. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:12071. [Google Scholar]; b Vandewalle M, De Clercq P. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:1767. [Google Scholar]

- 40.a Singh V, Iyer SR, Pal S. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:9197. [Google Scholar]; b Tokoroyama T. Synthesis. 2000:611. [Google Scholar]; c Varner MA, Grossman RB. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13867. [Google Scholar]

- 41.a Stork G, Gardner JO, Boeckman RK, Jr., Parker KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2014. [Google Scholar]; b Stork G, Boeckman RK., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Equilibration of decalones is highly substitutent-dependenta with some syntheses encountering only modest preferences for one ring junction stereochemistry.b-c Thompson HW, Long DJ. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:4201.White RD, Wood JL. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1825. doi: 10.1021/ol015828k.Kametani T, Kato Y, Honda T, Fukumoto K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:8185.

- 43.Fleming FF, Shook BC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:2885. doi: 10.1021/jo016156e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The relative stabilities of cis and trans hydrindanes depends on temperature and substitution pattern, with angularly substituted cis-hydrindanes generally being more stable than their trans-hydrindane counterparts: Eliel Ernest L., Wilen Samuel H., Mander Lewis N. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley, NY: 1994. pp. 774–775.

- 45.a Fleming FF, Gudipati S, Aitken J. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6961. doi: 10.1021/jo0711539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fleming FF, Gudipati S. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1557. doi: 10.1021/ol060010q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.For a related cyclization to an angular nitrile-containing hydrindane see: Sato M, Suzuki T, Morisawa H, Fujita S, Inukai N, Kaneko C. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1987;35:3647.

- 47.a Fleming FF, Vu VA, Shook BC, Rahman M, Steward OW. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1431. doi: 10.1021/jo062270r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fleming FF, Shook BC, Jiang T, Steward OW. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:737. [Google Scholar]; c Fleming FF, Shook BC, Jiang T, Steward OW. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1547. doi: 10.1021/ol990854s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Use of the lithium alkoxide is critical because the magnesium alkoxide readily eliminates: Fleming FF, Shook BC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3668. doi: 10.1021/jo0162944.Fleming FF, Shook BC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8847.

- 49.a Davis FA, Mohanty PK. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:1290. doi: 10.1021/jo010988v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Davis FA, Mohanty PK, Burns DM, Andemichael YW. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3901. doi: 10.1021/ol006654u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Schrader T, Kirsten C, Herm M. Phosphorous, Sulfur, Silicon. 1999:144–146. 161. [Google Scholar]; d Gmeiner P, Hummel E, Haubmann C. Liebigs Ann. 1995:1987. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19953280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Murray Murray AWND, Reid RG. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986:1230. [Google Scholar]

- 50.a Kakiuchi F, Sonoda M, Tsujimoto T, Chatani N, Murai S. Chem. Lett. 1999:1083. [Google Scholar]; b Henbest HB, Nicholls B. J. Chem. Soc. 1959:227. [Google Scholar]; For a related interaction between fluorine and the nitrile π-electrons see: Nishide K, Hagimoto Y, Hasegawa H, Shiro M, Node M. Chem. Commun. 2001:2394.

- 51.Chelation of nitriles by lithium cations is directly analagous to the chelation of organolithiums with proximal alkenes and aromatic π systems: Harris CR, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8434.Rölle T, Hoffmann RW. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. II. 1995:1953.Bailey WF, Khanolkar AD, Gavaskar K, Ovaska TV, Rossi K, Thiel Y, Wiberg KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5720.

- 52.Fleming FF, Wei Y, Liu W, Zhang Z. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7477. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.05.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klumpp GW. Rec. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 1986;105:1. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sumrell G. J. Org. Chem. 1954;19:817. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Analogous Cu(III) species were verified as key intermediates during coupling of lithium dimethyl cuprate with halobenzenes,a although the lifetime of this intermediate may be short since a Cu(III) intermediate was not detected by 13C NMR during the reaction of Me2CuLi with 1-bromocyclooctene.b Spanenburg WJ, Snell BE, Su M-C. Microchem. J. 1993;47:79.Yoshikai N, Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12264. doi: 10.1021/ja046616w.

- 56.The A-value of a nitrile is only 0.2 kcal mol−1.3

- 57.a Swiss KA, Liotta DC, Maryanoff CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:9393. [Google Scholar]; b Turova NY, Turevskaya EP. J. Organomet. Chem. 1972;42:9. [Google Scholar]