Abstract

Objectives. To identify reasons for inclusion of international practice experiences in pharmacy curricula and to understand the related structure, benefits, and challenges related to the programs.

Methods. A convenience sample of 20 colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States with international pharmacy education programs was used. Telephone interviews were conducted by 2 study investigators.

Results. University values and strategic planning were among key driving forces in the development of programs. Global awareness and cultural competency requirements added impetus to program development. Participants’ advice for creating an international practice experience program included an emphasis on the value of working with university health professions programs and established travel programs.

Conclusion. Despite challenges, colleges and schools of pharmacy value the importance of international pharmacy education for pharmacy students as it increases global awareness of health needs and cultural competencies.

Keywords: global health, international education, pharmacy education, international practice experience, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

At its 2008 annual meeting, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) identified “globalization of pharmacy education” as a major initiative to be pursued.1 In 2009, the AACP charged the Research and Graduate Affairs Committee with the task of evaluating the role AACP and its members should play in the area of global health. In its final report, the committee recognized the role that many pharmacy schools and their individual faculty members already have in this area. However, the committee noted the “low profile amongst US government agencies” of pharmacy efforts, which could make funding support difficult.2

Two AACP surveys (conducted in 2007 and 2010) found that many US colleges and schools of pharmacy have some type of international program.3,4 Of 63 colleges and schools that responded to the 2007 survey, 39 reported international programs, with 29 of those reporting formal articulation or affiliation agreements with foreign universities and international organizations. Because of these relationships, transnational partnerships were initiated and enabled activities such as faculty and student exchanges, collaborative research, and practice experiences.3 The 2010 survey indicated that interest had grown with more colleges and schools reporting involvement or anticipation of involvement.4

This increase in interest has been recognized by AACP with its establishment of the Global Pharmacy Education Special Interest Group. The purpose of the group is to “provide a forum for the exchange of information, ideas and programs that pertain to pharmacy education, research and healthcare on a global basis.”5 This special interest group will also support global initiatives of the AACP, such as the Global Alliance for Pharmacy Education. The World Health Organization, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, and the International Pharmaceutical Federation formed the Pharmacy Education Taskforce, which developed a 2008-2010 action plan to promote and develop pharmacy education on a global scale.6

As the number of colleges and schools of pharmacy increases, interest in expanding curricula to include international collaborative practice experiences for faculty and students might also be expected to grow. In a discussion of what was needed to successfully expand pharmacy education globally, Alsharif discussed several strategies, including encouraging schools to make the global health area an integral part of planning and curriculum design.7 He particularly noted that schools should “empower, inspire, and motivate faculty members and students to contribute to solving the issues facing the global village.”7

For interested students, some colleges and schools of pharmacy offer academic credit for advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) outside of the United States, allowing student pharmacists to participate in global health initiatives. The major objective of this study was to identify reasons why US colleges and schools of pharmacy include international practice experiences in their curricula, and also to understand the structure, benefits, and challenges related to the programs. The authors also explored recommendations and future directions.

METHODS

The study used qualitative, semi-structured interviews. A semi-structured phone interview technique enabled the interviewers to follow the list of predetermined questions and also allowed for flexibility in pursuing related topics or themes to enhance understanding. Twenty colleges and schools of pharmacy with known international practice experiences were randomly selected as a convenience sample from a combined list of schools which were provided in the previous studies of AACP3,4 and from other schools known to provide such experiences. The 20 institutions were randomly divided between 2 interviewers who then contacted the colleges and schools to determine who best to discuss their international pharmacy education program with. The individuals were then contacted, the purpose of the study was explained, and each was invited to participate in the interview. All invited individuals and colleges and schools agreed to participate.

Two members of the investigator team were selected to conduct the interviews because of their experience and to minimize variability in the interview process which might affect the rigor of the data collection and results of the study. Guided interview questions were developed in consideration of the study objectives and after review of studies related to this topic.3,4

At the beginning of each interview, the investigator assured the participant that all the information collected in the study would be kept strictly confidential and only aggregate data would be reported. Once the participant agreed to take part in the study, the investigator began the interview session. Individual responses of the participants were recorded, with each interview lasting 30 to 45 minutes.

Information collected via the semi-structured interviews was analyzed by the investigator team. Quantitative data were tallied and represented using descriptive statistics. Participants’ qualitative responses to the interviews were analyzed by the project team through the content analysis method in which responses were categorized.8,9

All of the investigators reviewed and discussed the results via conference calls. When discrepancies were found in the interpretation of the analysis, the investigators discussed and reexamined the data until a consensus was reached. Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from all investigators’ institutions prior to the implementation of the study.

RESULTS

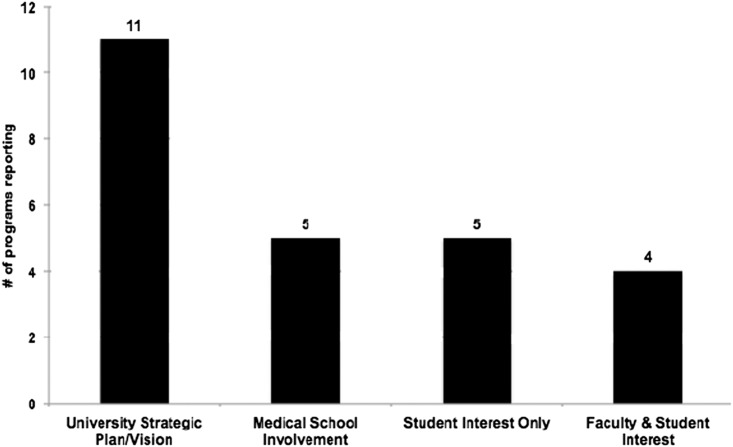

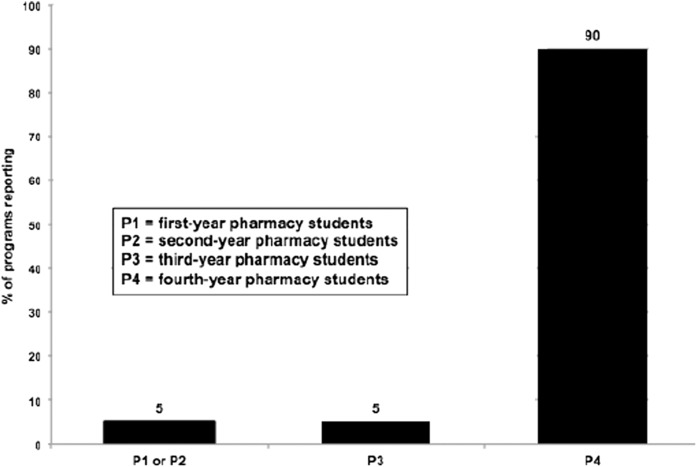

University values, strategic planning, the involvement of a university’s medical school in international programs, and faculty and student interest were the key driving forces in the initiation and expansion of international pharmacy education programs. Some colleges and schools reported multiple reasons (Figure 1). The desire to increase the global awareness and cultural competency of pharmacy students added impetus to program development. The programs surveyed indicated that student enrollment in international pharmacy education programs was competitive and selective. All but one of the institutions offered elective credit hours for these experiences, with most offering international practice experiences during the final clerkship/practice experience year (Figure 2). The school that did not provide academic credit hours did recognize international experience on a student’s transcript.

Figure 1.

Reasons for Initiation and Expansion of International Pharmacy Education Programs. Total number of programs more than 20 because of multiple reasons reported from some schools.

Figure 2.

Pharmacy Student Academic Year of International Practice Experience.

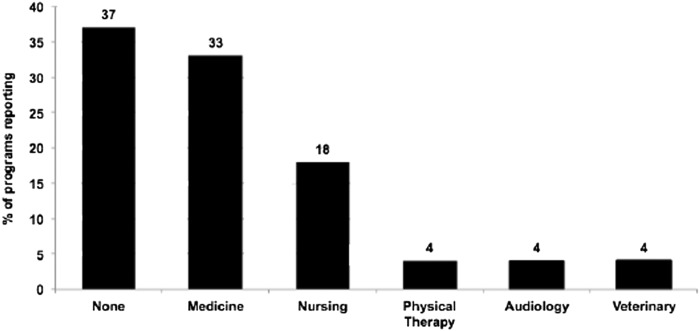

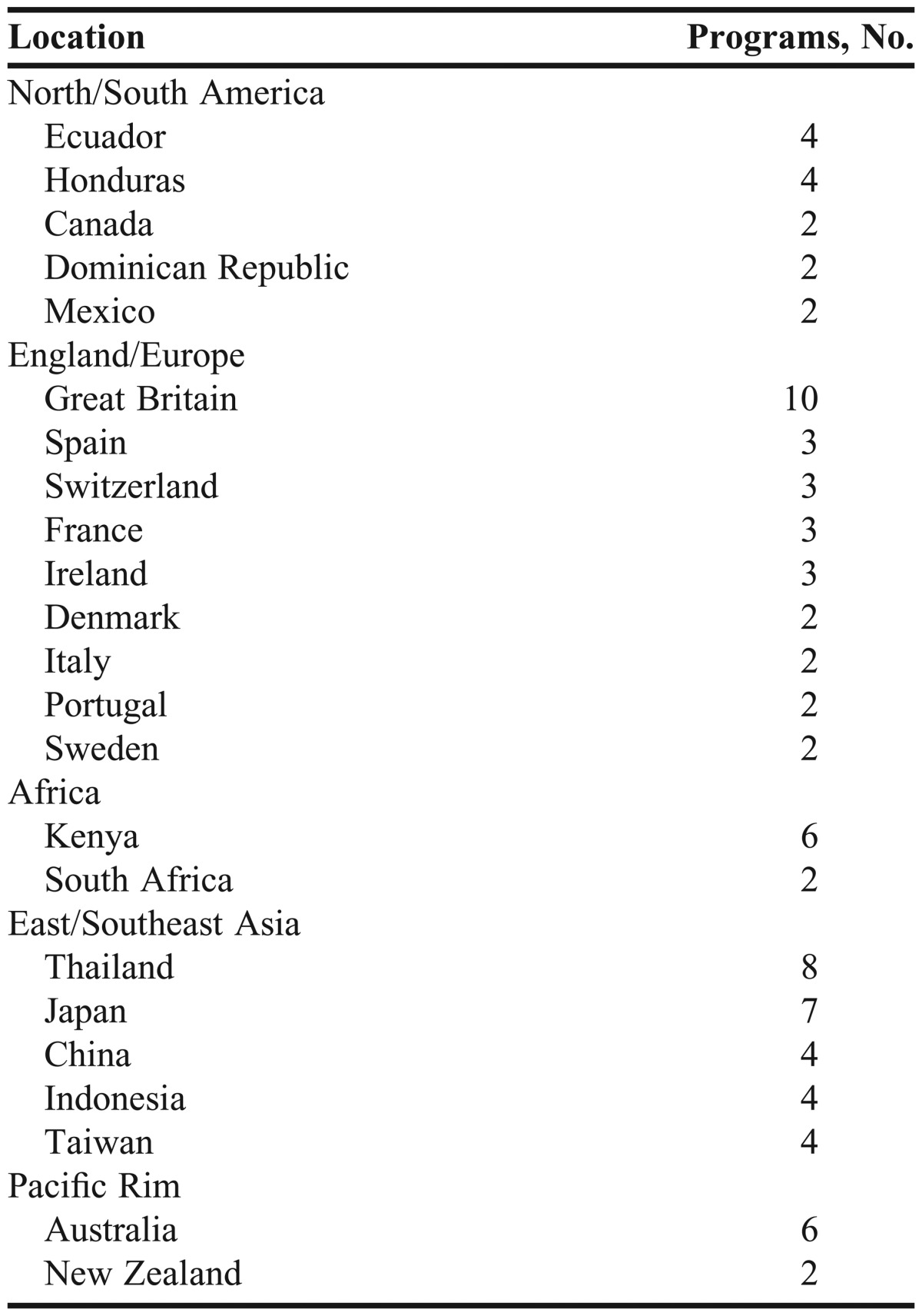

The list of countries where the programs offered international practice experiences was extensive (Table 1), with the United Kingdom (10), Thailand (8), and Japan (7) being the most frequently visited countries. The reasons for choosing a particular international site varied but included strengthening US faculty relationships with international faculty members and institutions, collaborating for student-initiated research projects, and development of more formal partnerships, such as the US Consortium for the Development of Pharmacy Education in Thailand. Approximately two-thirds of the schools reported that their international practice experiences were interdisciplinary in nature, with medicine (33%) and nursing (18%) being the most common joint participants (Figure 3). Faculty participation in international practice experiences varied and, in many cases, visiting pharmacy students were supervised by preceptors who were either local pharmacy practitioners or from another discipline (eg, medicine, nursing), or supervision was provided by both.

Table 1.

International Pharmacy Education Programs Reported by 20 US Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy

Figure 3.

Pharmacy and Health Professions Programs Collaboration for International Practice Experiences. Total number of programs=20. Some schools reported collaboration with more than 1 health professions program.

Student activities performed during international practice experiences consisted of traditional dispensing functions but also included providing primary care, conducting research, and learning about other healthcare systems. Schools obtained feedback from participating students who indicated that an international pharmacy education experience was a special event, both professionally and personally.

The colleges and schools noted several challenges to the successful implementation of international pharmacy practice experiences. These included logistics (travel, visas, etc), financial considerations, and communication with the international site. In almost all cases, the students participating in international pharmacy practice experiences were responsible for their own expenses. Advice given by study participants to other colleges and schools of pharmacy that may be interested in establishing international pharmacy education programs included an emphasis on the value of working with other campus-based health professions groups as well as using the offices of university international programs, such as Study Abroad, to share resources and assist with program development and implementation.

DISCUSSION

Despite the considerable amount of time invested in the development of international pharmacy education programs, representatives of 20 US colleges and schools of pharmacy indicated that these practice experiences were highly valued. Two key contributing factors were cited. The gratification of helping to develop a successful program that the students found to be a positive learning experience justified the time commitment. The opportunities to contribute to enhanced student cultural awareness and to provide positive personal experiences were considered instrumental to the process.

Universities across the United States have shown increased interest in global health care10 and this attention parallels the impact of globalization on many other areas of society including economics.7 At least 3 motivating forces are attributed to this increase: (1) changes in higher education that emphasize internationalization, (2) increased visibility of healthcare needs on a global scale, and (3) an expansion of resources from all sectors that has resulted in increased opportunities for universities and for students.10 While we found evidence of all 3 drivers in the initiation of international pharmacy education experiences, the emphasis of universities on internationalization via strategic planning and prioritization, and the awareness of global healthcare needs via the media played the largest role. Equally important was the mutual exchange of ideas and experiences by transnational travelers and healthcare workers.

While the “majority of college graduates now enter the workforce with some kind of global experience on their resume,”10 participants indicated that students chose, and were enriched by, pharmacy education experiences in other countries, not because the experience was a “resume builder,” but rather out of a deep-rooted desire to learn about people from other cultures and to contribute to global healthcare needs. Faculty and staff members stressed, as did Alsharif, that “instead of having Western societies as the main reference point and Western education as the norm for all learning levels, local needs should be a critical driver as well as any local practice models or education experiences that the West can learn from.”7

“Respect” was a term often used by participants. This resonates well with Alsharif’s view that key strategies include the “Respect [for] historic factors and ethical dilemmas which may have influenced pharmacy education and practice in a region of the world.”7 The expected outcome of these practice experiences was often to enhance students’ understanding of culture and public health practices in the countries visited. For most students, this was an enriching experience. Participants also noted that students found the professional practice models at the international sites interesting. Additionally, through immersion education, students were able to celebrate differences in culture, and they realized that they were part of a much larger global community.

Advice to colleges and schools of pharmacy who are starting or expanding international pharmacy education programs followed a few core themes. Colleges and schools should be strategic about which sites to develop relationships and initiate programs with (Figure 1). While student and faculty interests were important in helping to identify specific types of international practice experiences, participants most frequently mentioned the university’s own vision or strategic plan as a driving force which led to the overall desire to develop international practice experiences. Several participants indicated they thought it was important to set up international pharmacy education programs in countries where US-based faculty members already have established cultural or professional ties.

Also, colleges and schools should develop sustainable and long-lasting programs instead of 1-time endeavors. This would require strong linkages in both directions, including the development of dedicated and well-trained instructors in the US and abroad. Colleges and schools developing new programs were encouraged to realize the purpose of global education and to think about outcomes relative to the resources expended. They were reminded to engage in international programs and relationships with the understanding that, while a large amount of time will go into their development, many positive outcomes can ensue.

The placement of international practice experiences in the curricula of colleges and schools seemed to fit most frequently in the final year along with other APPEs (Figure 2). The ability to offer international practice experiences earlier may be limited because of the required coursework schedule, with less opportunity for individualization and variation than the final year allows.

This study reports the views and opinions of a convenience sample of 20 academic administrators and faculty members of US colleges and schools of pharmacy with known international practice experience programs. No generalizations can be made to the experiences and recommendations of other colleges and schools with similar programs that were not included. Potential bias could have been created by differences in technique and methods used by the interviewers. Efforts were made to minimize bias by limiting the number of interviewers as well as by using a standard script.

CONCLUSION

As colleges and schools of pharmacy continue to develop global health initiatives, it is important to develop relationships at appropriate sites to make sure that pharmacy students are achieving the goals and outcomes for the specific experience. Both the students and the experiential sites need to benefit from these experiences. As global health issues continue to be important, colleges and schools of pharmacy should examine ways to enhance global experiences for pharmacy students by reaching out to faculty and maintaining international relationships, taking advantage of existing university services and relationships, and collaborating with other health professions programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank AACP and all those affiliated with the 2011-2012 Academic Leadership Fellows Program. We gratefully acknowledge the mentorship and support of Kenneth B. Roberts, Dean Emeritus, at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yanchick V. Thinking off the map. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;72(6):Article 141. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audus KL, Moreton JE, Normann SA, et al. Going global: the report of the 2009-2010 Research and Graduate Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article S8. doi: 10.5688/aj7410s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagraves R. Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2007. Survey of US colleges and schools of pharmacy concerning international education and research relationships [unpublished raw data] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagraves R. Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2010. Survey of current global affiliations of US colleges and schools of pharmacy [unpublished raw data] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AACP. Global Pharmacy Education Special Interest Group of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Bylaws. http://www.aacp.org/governance/SIGS/global/Documents/GlobalPharmEdSIGBylaws7-09.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2013.

- 6.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce. Hum Resour Health. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-45. http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/7/1/45. Accessed April 16, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alsharif N. Globalization of pharmacy education: what is needed? Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(5):Article 77. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdan R, Biklen SK. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. New Jersey: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morse J, Field P. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merson MH, Page KC. Center for Strategic & International Studies. The Dramatic Expansion of University Engagement in Global Health: Implications for US Policy. April 2009. http://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/090420_merson_dramaticexpansion.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]