Abstract

Objectives. To describe the work factors associated with 28 different career areas as reported by pharmacists who responded to the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Career Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals, 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey

Methods. Data from the 1,119 completed survey instruments from the 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey were analyzed. Exploratory factor analysis was used to identify the underlying factors that best represented respondents’ work setting profiles.

Results. Eleven underlying factors were identified for the respondents’ work setting profiles: patient care, application of clinical knowledge, innovation, stress, research, managerial responsibility, work schedule flexibility, job position flexibility, self-actualization, geographic location, and continuity of coworker relationships. Findings revealed variation for these underlying factors among career categories.

Conclusion. Variation among pharmacist career types exists. The profiles constructed in this study describe the characteristics of various career paths and can be helpful for decisions regarding educational, experiential, residency, and certification training in pharmacist careers.

Keywords: pharmacist, career, work setting profile, pharmacist, survey

INTRODUCTION

The transformation in pharmacy education to the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree as the sole professional degree for pharmacy in the United States and the increase in pharmacist residency training have created new competencies for taking on expanded responsibility for optimizing medication use in the US healthcare system.1 The pharmacy profession has been building capacity so that pharmacists are ideally suited to serve in new roles such as being medication care coordinators for patient-centered medical homes2,3 and primary care teams,4-7 members of chronic disease management teams that focus on “episodes” of care in which related services are packaged together,8,9 and the healthcare professional responsible for ensuring optimal medication therapy outcomes through medication therapy management service provision.10-17

Pharmacists are faced with an array of choices about job positions and educational pathways that can enhance their careers.18-23 To help individuals in the pharmacy profession learn about various career options that might fit their interests and skills, the Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals was developed by Glaxo Pharmaceuticals in the 1980s. This program allowed individuals to match their interests and skills with career profiles to help determine which career options might be most suitable for them. The career profiles for the program were developed and updated through a series of surveys from respondents who worked in the career categories covered by the program. The initial Glaxo Pharmacy Specialty Survey was conducted in fall 1988. In an effort to keep the information current, the Glaxo Pharmacy Specialty Survey was conducted again in spring 1993.24

By 2002, the APhA maintained the program and the 2002 Career Pathway Evaluation Program Pharmacist Profile Survey was conducted to update the career profiles. The APhA constructed the sampling frame using lists from its own records, organizations that represented the career types, personal contacts, and advisory panels. The goal was to construct a sampling frame that represented pharmacists in each of the respondent categories used for the program.25,26 The profile survey was repeated in 2007 using a Web-based data collection technique and expanded to include more measurement items than the 2002 survey instrument and both pharmacist and pharmaceutical scientist career pathways.27,28 Using the 2007 survey instrument as a template, the profile survey was repeated in fall 2012. (The 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey is available from the corresponding author upon request.)

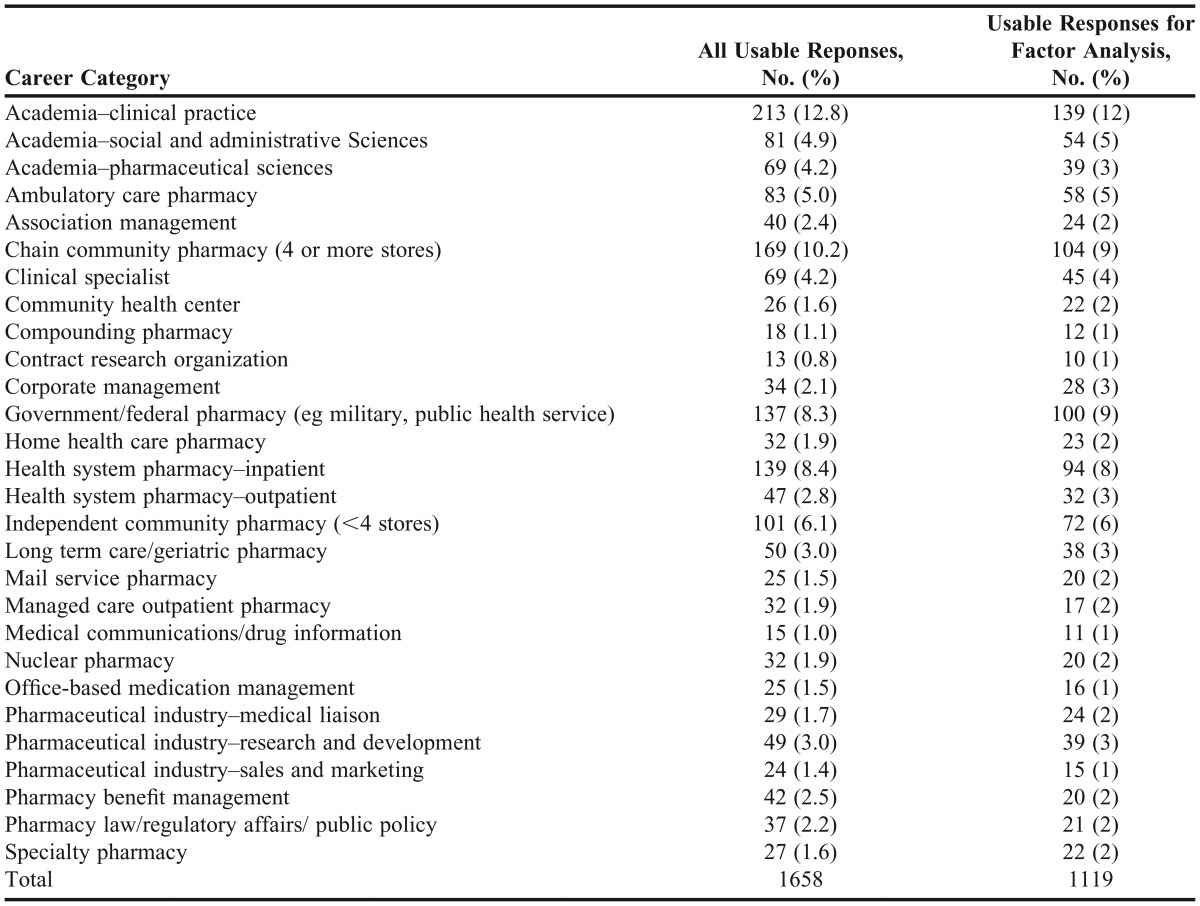

The objectives for this study were to use a portion of the 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey as a data source to investigate the underlying factor structure of respondents’ practice profiles that were created using the 45 items in section 2 of the survey instrument and use the resulting factors to describe the 28 different career pathways listed in the survey instrument (Table 1). The results can provide insight about the underlying factor structure of pharmacist careers in 2012 and can be used to describe various career paths that were open to pharmacists in 2012.

Table 1.

Data From the 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey Used to Analyze Work Setting Variables

METHODS

The data source for this study was the APhA Career Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey. The survey instrument consisted of 5 sections that collected information about respondents’ primary work setting, work setting profile, workload and work activities, background information, and open-ended written opinions regarding career choices and about the survey form. We used data collected from section 2 of the survey instrument. This section contained 45 items that asked respondents about the degree to which each work characteristic described their work setting. Each item was rated on a 10-point scale. The items were selected by an expert panel to represent a broad range of career categories; for example, the time spent performing physical assessments, the time spent conducting research, and the time spent managing business operations. Items covered several facets of work settings from the time pharmacists spent in various activities (eg, patient care, management) to the benefits offered (eg, job sharing, parental leave). This information provided the level of detail necessary for creating career profiles within the Career Pathway program.

A Web-based data collection technique was used for the 2012 survey. Through a purposive sampling process, individuals who fit 1 of the career categories in the survey instrument (Table 1) were identified by an expert panel that convened via conference call on a regular basis for identifying and inviting potential respondents to participate. Both individual (eg, personal e-mails) and broadcast (eg, newsletters) invitations were used for recruiting survey respondents.

Invitations were sent from November 2012 through January 2013. The 1,658 survey forms submitted to 1 of the 28 career categories were downloaded from the host site on February 11, 2013. Of these, 1,119 contained usable data for each of the 45 items included in the factor analysis (Table 1). Based on sample size requirements for estimating analysis of variance statistics, our goal was to have at least 14 respondents in each of the 28 categories. Three categories did not meet this goal and findings for these categories should be viewed with caution (compounding pharmacy (n=12), contract research organization (n=10), and medication communications/drug information (n = 11)).

For the first objective, exploratory factor analysis was used to investigate the underlying factor structure of respondents’ work profiles that were created using the 45 items in the survey instrument. Factor analysis describes the structure of a correlation matrix. It also categorizes a large number of variables into a few factors. Varimax rotation was used for factor analysis to maintain orthogonality (independence) of factors and to minimize the number of variables that had high loadings on a factor. Only factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were included in the factor solution. In addition, only items with factor loadings with absolute values ≥0.50 on 1 and only 1 factor were included for identifying factors. This was done to maintain orthogonality among factors, establish parsimony in the application of the factors, and provide comprehensibility for interpretation of findings.

Scores for the overall factors were computed by summing the scores of the items that loaded on the corresponding factor. Each factor was assigned a name based upon the items that comprised that particular construct. Means, standard deviations, and measure reliability (Cronbach coefficient alpha) were computed for each factor.

For the second objective, mean scores for the resulting factors were used to describe the 28 different career pathways listed in the survey instrument. Analysis of variance was used to ascertain that mean scores for the factors differed significantly among the 28 career categories.

RESULTS

Forty-two of the 45 items met our factor analysis criteria (loaded on a factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1, exhibited a factor loading with an absolute value ≥0.50, and loaded on 1 and only 1 factor). The 3 items that were dropped from analysis did not have a factor loading ≥0.50 on any of the 11 resulting factors. Each factor was assigned a name based on the items that comprised that particular construct. Detailed results from our analyses are available from the author.

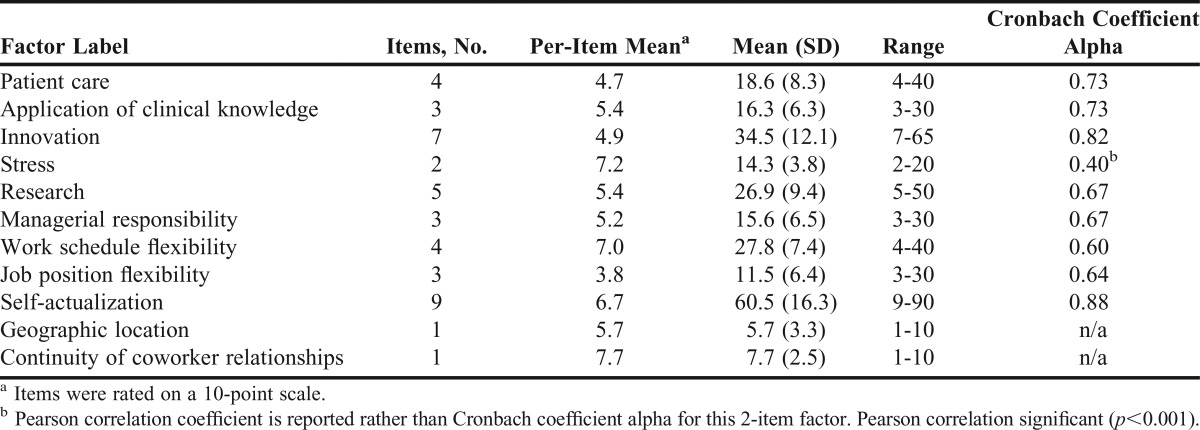

The 11 factors we identified were patient care, application of clinical knowledge, innovation, stress, research, managerial responsibility, work schedule flexibility, job position flexibility, self-actualization, geographic location, and continuity of coworker relationships (Table 2). Based on per-item means, the 3 highest scores for the respondents were for the factors continuity of coworker relationships (7.7), stress (7.2), and work schedule flexibility (7.0). The 3 lowest scores were for the factors job position flexibility (3.8), patient care (4.7), and innovation (4.9). Per-item mean scores for the factors were compared among the 28 respondent categories using ANOVA. For each factor, there were significant differences in scores among career categories (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Underlying Factors Identified for Respondents’ Work Setting Profiles

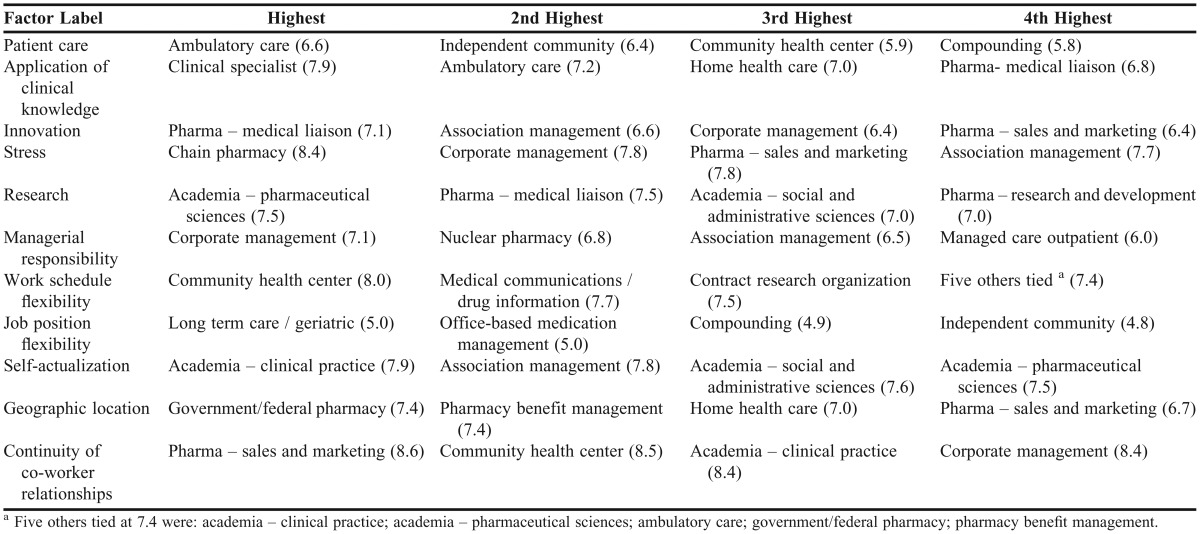

The career categories with the highest 4 scores for each factor are presented in Table 3. The career categories that scored highest for the patient care factor were ambulatory care pharmacy (6.6), independent community pharmacy (6.4), and community health center (5.9). Highest scoring career categories for the application of clinical knowledge factor were clinical specialist (7.9), ambulatory care pharmacy (7.2), and home health care pharmacy (7.0).

Table 3.

Career Categories With the Highest Per-Item Mean Scores for Each Factor

The highest scores for the innovation factor were reported by pharmaceutical industry–medical liaison (7.1), association management (6.6), corporate management (6.4), and pharmaceutical industry–sales and marketing (6.4). The stress factor scores were highest for chain pharmacy (8.4), corporate management (7.8), and pharmaceutical industry–sales and marketing (7.8). For the research factor, the highest scores were reported by academia–pharmaceutical sciences (7.5), pharmaceutical industry–medical liaison (7.5), academia–social and administrative sciences (7.0), and pharmaceutical industry–research and development (7.0).

Managerial responsibility factor scores were highest for respondents categorized as corporate management (7.1), nuclear pharmacy (6.8), and association management (6.5). Work schedule flexibility factor scores were highest for community health center (8.0), medical communications/drug information (7.7), and contract research organization (7.5). Scores for the job position flexibility factor were highest for long-term care/geriatric pharmacy (5.0), office-based medication management (5.0), and compounding pharmacy (4.9).

For the self-actualization factor, the highest scores were reported by respondents categorized as academia–clinical practice (7.9), association management (7.8), and academia–social and administrative sciences (7.6). Geographic location factor scores were highest for the government/federal pharmacy (7.4), pharmacy benefit management (7.4), and home health care (7.0) categories. Scores for the continuity of coworker relationships factor were highest for respondents categorized as pharmaceutical industry–sales and marketing (8.6), community health center (8.5), academia–clinical practice (8.4), and corporate management (8.4).

DISCUSSION

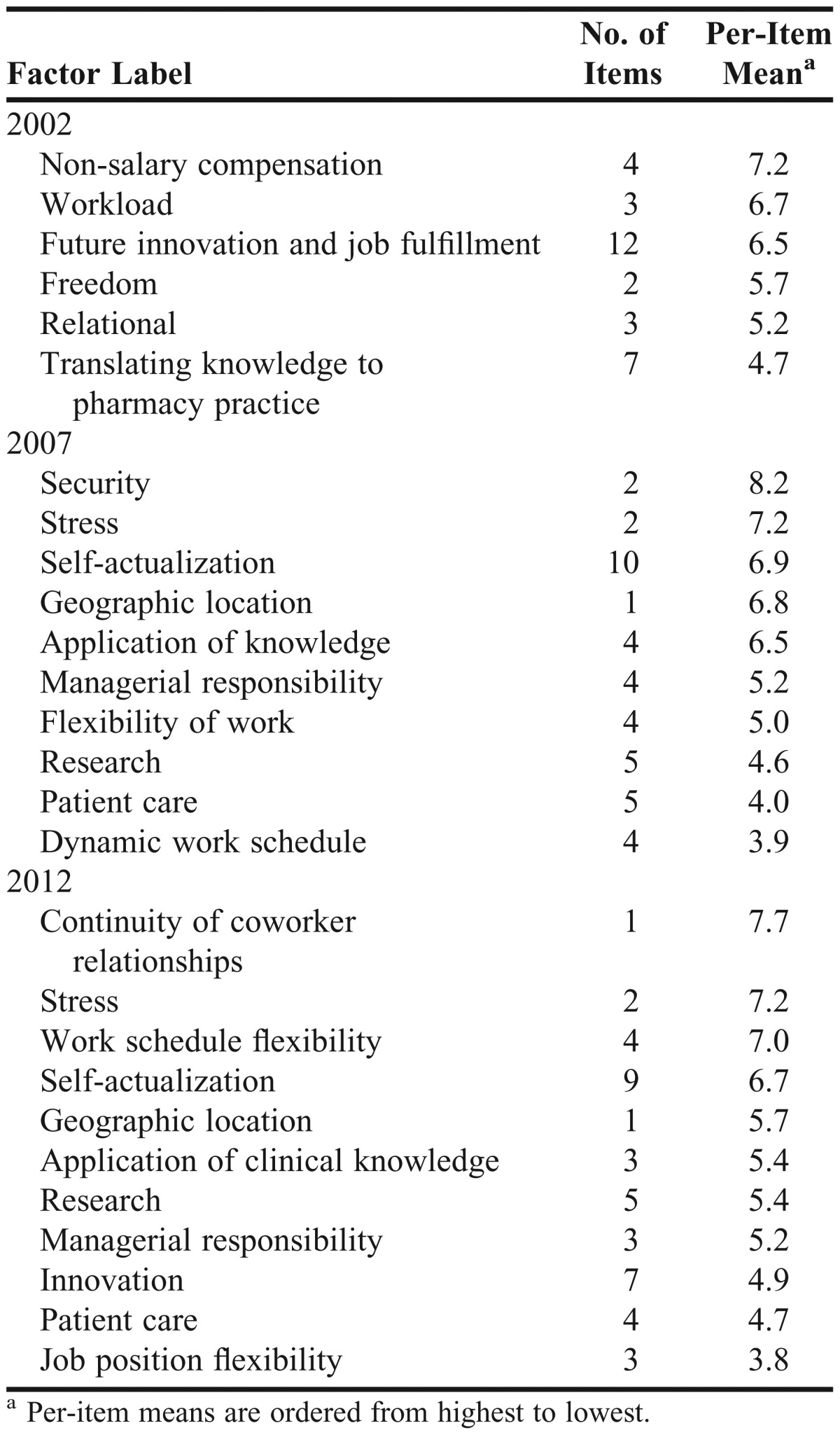

The results of this study provide insight about the underlying factor structure of the 45 items in the APhA Career Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey. After grouping the 42 items that met our analysis criteria into 11 factors, we compared the 6 factors identified in the 2002 survey25 with the 10 factors identified in the 2007 survey28 and the 11 factors identified in the 2012 survey (Table 4). The 2012 survey was an improvement over the 2002 and 2007 surveys in that more factors for more career paths were identified and described with greater detail.

Table 4.

Comparison of Factors Identified in 2002, 2007, and 2012 Studies

The profiles constructed in this study could be helpful to individuals as they consider various career paths and as they choose elective coursework during their pharmacy education. If a pharmacy student is interested in careers offering opportunities for patient care, the profiles show that careers in ambulatory care pharmacy, independent community pharmacy, and community health center areas scored highest for involving patient care (Table 3). Career pathways that scored highest for allowing/encouraging self-actualization were academia–clinical practice, association management, and academia–social and administrative sciences.

The results of this study may be useful for educators who advise pharmacy students about various career options. Student interests could be matched with elective courses, practice experiences, and participation in research (Table 3). In addition, the results could be used to identify new elective courses or practice experiences that might be needed for comprehensive and relevant pharmacy education. One of the reasons for updating the profile periodically for the Career Pathway program comes from acknowledging that not only do career opportunities change, but pharmacy student priorities and desires for career pathways change. Our research can be used for evaluating and developing curricula for pharmacy education to help meet those changing needs.

The 11 factors we identified could be associated with quality of work life, job stress, job satisfaction, career commitment, and job turnover intention.29,30 Although we did not study causal relationships, the Career Pathway Evaluation Program contains descriptive items that would be useful to pharmacists who wish to learn more about factors that could impact the quality of their work life. The profiles constructed could be helpful to pharmacists as they consider various career paths, and as they choose educational, experiential, residency, and certification training during their pharmacy career.

The findings also provide insight for future research in this area, particularly the next Career Pathway Evaluation Program Profile Survey. Future survey instruments could include more items related to factors that currently only have a few items describing them (continuity of coworker relationships, stress, and geographic location).

As the results are considered, some of the limitations of the research should be kept in mind. Noncoverage bias could have existed. While great effort was devoted to identifying pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists for the career categories in this study, the lists we developed were neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive. There were relatively small sample sizes for some career categories. Based on sample sizes needed for conducting ANOVA, results for career categories with fewer than 14 responses should be viewed with caution. Because of sample size limitations, we did not further categorize respondents by demographic variables such as gender, position, or years of experience. Future studies should investigate how such demographic variables affect the results. Respondents were identified and recruited using purposive sampling techniques (nonrandom); therefore, results should not be used for making population estimates. Our goal was to differentiate among the various career pathways described. While the 45 survey items included may not have been an exhaustive list, they garnered the information used to compile accurate pharmacy professional work profiles and describe the career options that were open to pharmacists in 2012. Our findings are descriptive only. They cannot be used to answer questions about “why” career pathways differed.

CONCLUSION

Our analysis of data taken from the APhA’s 2012 Pharmacist Profile Survey identified 11 underlying factors to the pharmacist work setting profiles structure. Future research that investigates how representative these 11 factors and the underlying measurement items are to individuals who are seeking career guidance would be helpful. The results also revealed variation among pharmacist career types. The profiles constructed in this study describe the characteristics of various career paths and can be helpful for decisions regarding educational, experiential, residency, and certification training in pharmacist careers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Funding for this study was provided by the American Pharmacists Association. The authors gratefully acknowledge Elizabeth Cardello, Maria Gorrick, Gina Scime, and Krystalyn Weaver for serving on an expert advisory panel for this survey and for coordinating data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schommer JC, Planas LG, Johnson KA, Doucette WR, Gaither CA, Kreling DH, Mott DA. Pharmacist contributions to the U.S. healthcare system. Innov Pharm. 2010;1(1):Article 7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dettloff RW, Glosner P, Moroney SM. Establishing the role of the pharmacist in the patient-centered medical home: the opportunity is now. J Pharm Technol. 2009;25:287–291. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb CE. Integration of Pharmacists’ Clinical Services in the Patient-Centered Primary Medical Home. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2009. http://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/IntegrationPharmacistClinicalServicesPCMHModel3-09.pdf, Accessed August 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gebhart F. Put pharmacists on primary care team, says Perdue CMO. Drug Topics. 2010;154(1):23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in primary care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56(16):1665–1667. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manolakis PG, Skelton JB. Pharmacists’ contributions to primary care in the US collaborating to address unmet patient care needs: the emerging role for pharmacists to address the shortage of primary care providers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article S7. doi: 10.5688/aj7410s7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobson RT, Taylor JG, Henry CJ, et al. Taking the lead: community pharmacists’ perception of their role potential within the primary care team. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2009;5(4):327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: advancing team-based care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1945–1948. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.24. Goff Jr. DC, Greenland P. The change we need in health care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):737–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen JA, Burns A. The Pharmacist in Public Health: Education, Applications, and Opportunities. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2010. Medication use, related problems and medication therapy management. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Planas LG, Kimberlin CL, Segal R, et al. A pharmacist model of perceived responsibility for drug therapy outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2393–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett MJ, Frank J, Wehring H, et al. Analysis of pharmacist – provided medication therapy management (MTM) services in community pharmacies over 7 years. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(1):18–31. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassol A, Shoemaker SJ. Exploratory Research on Medication Therapy Management: Final Report. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SR, Clancy CM. Medication therapy management programs: forming a new cornerstone for quality and safety in medicare. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(4):276–279. doi: 10.1177/1062860606290031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Lewin Group. Medication therapy management services: a critical review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45(5):580–587. doi: 10.1331/1544345055001328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schommer JC, Planas LG, Johnson KA, Doucette WR. Pharmacist-provided medication therapy management (part 1): provider perspectives in 2007. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):354–363. doi: 10.1331/japha.2008.08012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schommer JC, Planas LG, Johnson KA, Doucette WR. Pharmacist-provided medication therapy management (part 2): payer perspectives in 2007. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(4):478–486. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.08023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions. The adequacy of pharmacist supply: 2004 to 2030. December 2008; http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmsupply20042030.pdf. Accessed, September 15, 2012.

- 19.Chumney ECG, Gagucci KR, Jones KJ. Impact of a dual PharmD/MBA degree on graduates’ academic performance, career opportunities, and earning potential. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 26. doi: 10.5688/aj720226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodwin SD, Kane-Gill SL, Ng TM, et al. Rewards and advancements for clinical pharmacists. ACCP White Paper. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(1):114. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke JM, Miller WA, Spencer AP, et al. Clinical pharmacist competencies. ACCP White Paper. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):806–815. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson TJ. Pharmacist work force in 2020: implications of requiring residency training for practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(2):166–170. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knapp KK, Cultice JM. New pharmacist supply projections: lower separation rates and increased graduates boost supply estimates. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;4(4) doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.07003. 7:463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaxo Wellcome, Inc. Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals. 4th ed. North Carolina: Glaxo Wellcome, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schommer JC, Brown LM, Millonig MK, Sogol EM. Career pathways evaluation program: 2002 pharmacist profile survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 5. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown LM, Millonig MK, Rothholz M, Schommer JC, Sogol EM. Career pathways for pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(4):459–562. doi: 10.1331/154434503322226194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schommer JC, Sogol EM, Brown LM. Career pathways for pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47(5):563–564. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.07074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schommer JC, Brown LM, Sogol EM. Work profiles identified from the 2007 pharmacist and pharmaceutical scientist career pathway profile survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 2. doi: 10.5688/aj720102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaither CA, Nadkarni A, Mott DA, et al. Should I stay or should I go? The influence of individual and organizational factors on pharmacists’ future work plans. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47(2):165–173. doi: 10.1331/6J64-7101-5470-62GW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murawski MM, Payakachat N, Koh-Knox C. Factors affecting job and career satisfaction among community pharmacists: A structural equation modeling approach. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;485):610–620. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]