Abstract

With the increase of new pharmacy colleges and schools throughout the country, the number of open clinical academic pharmacy positions continues to grow. Considering the abundance of clinical faculty positions available nationwide and the increased likelihood of current pharmacy residents transitioning from residency directly into academia, pharmacy residents must be prepared to succeed in the role of new clinical faculty member. However, no blueprint or recommendations have yet been provided to facilitate this transition. The purpose of this review article is to evaluate the literature regarding transitioning pharmacy students and/or residents into faculty roles. The literature reviewed represents nursing, medical, graduate school, and engineering disciplines because no literature on this topic was available from the pharmacy profession. Based on the recommendations provided in the literature and on the authors’ experience at their college, they created a blueprint consisting of 7 components to help residents transition directly into their roles as faculty members.

Keywords: career, academia, pharmacy residents, clinical faculty, pharmacy faculty

INTRODUCTION

With the perceived continued shortage of pharmacists choosing to pursue careers in academia and the increase of new pharmacy colleges and schools throughout the country, the number of open academic pharmacy positions continues to grow.1 According to data from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, 307 first-time pharmacy faculty members were hired for the 2012-2013 academic year. Each year, many pharmacy colleges and schools conduct interviews for clinical-track faculty members at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Midyear Clinical Meeting (MCM). A search on the ASHP CareerPharm database for the 2012 MCM listed 103 faculty positions, which included only those faculty positions that had been approved in early December. The trend our college of pharmacy observed at the 2012 MCM was that most applicants for these academic positions were current first- or second-year postgraduate (PGY1 or PGY2) pharmacy-practice residents. At our institution, approximately one-third to one-half of the new faculty members enter their positions after having completed a pharmacy practice PGY2 residency. Although the MCM is tailored toward current residents and new graduates, a significant number of the new clinical-track faculty positions are filled by recent residency graduates.

A PGY2 pharmacy resident at a local Texas Medical Center Hospital asked the following questions during the interview process: What does a college look for in hiring a resident as a clinical faculty member and how can I succeed in transitioning from resident to faculty member? Both questions may be in the minds of current residents seeking faculty positions, but there is no definitive answer to either. Each college and school has different standards for hiring new clinical faculty members. For instance, the hiring criteria might include that the candidate be either a PGY1, or PGY2, have a certain number of years of experience, or be a new pharmacy graduate. There also is no standard blueprint or leadership references specifically designed to help new clinical faculty members succeed in the transition from resident to academician: “the default preparation for a faculty career is none at all.”2

This article describes literature currently available regarding transitioning students and/or residents into faculty roles, identifies key traits for junior faculty member success from pharmacy and other healthcare-related professions, and establishes a baseline blueprint for transitioning pharmacy practice residents into successful clinical pharmacy faculty members. Although this article is intended to help deans and department chairs improve the transition of residents directly into clinical faculty roles, it may also be of use to new clinical faculty members, who may recommend to their respective institution’s leadership the principles described herein to facilitate their own transition.

EVALUATION OF LITERATURE

A PubMed search was conducted using the following terms: pharmacy, residents, and faculty members. The search returned 124 articles, none of which was identified as directly pertinent to the topic of transitioning residents directly into clinical faculty positions. Several articles are available describing academic practice experiences, longitudinal programs in academia, and faculty development.3-8 An article published in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education (AJPE) in October 2012 9 calls for standardized guidelines and interview process/timelines among US colleges and schools of pharmacy to maximize the time and effort put forth among each school in recruiting residents. In response to this article, a past resident who made the transition directly to faculty member supported the concept of a standardized interviewing timeline.10 In another article, which highlighted a lack of outcomes-oriented faculty-development programs in colleges and schools of pharmacy, the authors provided recommendations for improving faculty success in achieving tenure and promotion.11 While this article is an excellent resource, it does not specifically address the subpopulation of new faculty members transitioning directly from residency.

Using Google Scholar, an expanded search of university Web sites and professional organizations was conducted to determine if other disciplines have published literature on transitioning residents or students directly into faculty roles. Four articles were identified that described methods to improve the transition of trainees into faculty positions in medicine, nursing, engineering, and general PhD-level faculty position. The Clinical Faculty Survival Guide, a resource for new clinical pharmacy faculty members either having just completed a residency or having already practiced for several years, was also used.12

Medicine

An article published in The Journal of Academic Psychiatry highlights the clinician-educator tracks available for medical residents at 3 different programs throughout the country.13 The clinician-educator track was designed specifically for physicians in residency programs who are interested in pursuing clinical faculty jobs in academia after completing residency training. The goal of this multiyear program was to improve the teaching competency of junior physicians. The clinician-educator track program does not add years to a physician’s residency training but rather is completed concurrently in addition to the requirements of a physician’s residency program. This clinician-educator track is similar to teaching certificate programs offered by some colleges and schools of pharmacy to pharmacy residents but provides a deeper level of experience and training in academia because of the longer time period of instruction and content covered. Medical residents formally apply to these programs, the completion of which requires a multiyear, longitudinal commitment. Medical residents are paired with a faculty mentor and gain classroom teaching experience, leadership training, and introduction to effective scholarship principles. Participants are required to conduct an academic-related project, in addition to the mandatory clinical research they complete during residency. Mentors benefit from these trainees as they fulfill the role of faculty extenders for ongoing faculty projects.

According to a survey published in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, the majority of residency programs did not offer concentrated practice experiences in academia but did make longitudinal teaching practice experiences available to residents.5 The 1-year teaching certificate programs currently offered by pharmacy colleges and schools should meet the needs of most pharmacy residents. Because many residents who progress through our college’s teaching certificate program do not plan to pursue a career in academia, the teaching certification meets their needs by providing an entry-level course in providing lectures, writing test questions, mentoring, and other academic principles. Residents who have a strong interest in academia have 2 choices to gain more experience. They can choose a residency program that is paired with a college or school of pharmacy or that has a significant academic component, or they can seek out additional opportunities with lecturing, precepting, or getting involved in research with college faculty members. The success seen from the 3 clinician-educator programs previously described raises a question regarding whether another in-depth, comprehensive academia track is needed to prepare residents for a career in academia after residency. As many healthcare systems select PGY2 candidates from their own PGY1 resident pool, colleges and schools of pharmacy could develop a more in-depth, second-year teaching certificate program specifically designed to fulfill the goals of PGY2 residents interested in clinical faculty positions and higher levels of understanding regarding teaching and scholarship. A more in-depth teaching program for PGY2 residents has been developed at several colleges, an excellent example of which is the program at the University of Oklahoma.3

Doctor of Philosophy

There are several similarities between the transition from doctor of philosophy (PhD) student to faculty member, and that of pharmacy resident to clinical faculty member. However, the qualities that make an excellent student are not the same qualities that make a successful professor.14 Five key differences between student or resident responsibilities and faculty member responsibilities have been identified: lack of clarity, demands, pressure, self-motivation, and politics. With the exception of demands and pressure, most of these differences will be new to faculty members. Students are provided a clear understanding of the work to be completed to obtain their degree, typically with a standardized objective rubric or outline. For new faculty members, however, there may be a lack of clarity in either job requirements or research pathways. Another key difference, self-motivation, is an excellent quality for a student to possess but it is not absolutely necessary for a student to obtain a degree. In contrast, new faculty members must be self-motivated in order to succeed in the world of academia, and promotion and tenure are often directly related to this trait. Lastly, students may be given brief exposure to the politics at their respective universities, but they are not exposed to politics to the same extent they will be as a faculty member. Specific political issues such as hiring, tenure and promotion, collaboration on scholarship, teaching, and student grading are all aspects of politics to which the majority of residents will have minimal exposure.

Several strategies to prepare PhD students for this transition have been identified.14 It is important for new faculty members to be patient in finding their area of research and the getting research published. When several new faculty members were surveyed, they identified the difficulties in publishing and obtaining research grants as a source of frustration. One of the recommendations that emerged was that new faculty members focus on finding a niche in a specific research field and excelling in a particular area of research instead of spreading their scholarship efforts into several different categories. While scholarship is often not the main focus of clinical faculty members, these recommendations can be useful for new pharmacy faculty members.

Service and networking is crucial to success.14 New faculty members should network not only with faculty members in their own college but also with novice and experienced faculty members in other colleges and outside universities. New faculty members should take advantage of opportunities to attend conferences and network with other leaders across the country. The benefits of attending the annual American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) meeting has also been described as an excellent method of mentoring residents as they move into the academy.15 Finally, the importance of new faculty members choosing service and other opportunities wisely was emphasized. Junior faculty members often become flattered by different requests or responsibilities, resulting in their becoming overburdened with responsibility. New faculty members should get accustomed to saying no on a regular basis.

Nursing

Few professions have been hit as hard with a shortage of workers as faculty in colleges of nursing.16 Several state programs have even been created to provide funding for nurses to complete a graduate degree in exchange for committing to teach at a college of nursing once coursework has been completed. Recommendations for helping nurses successfully transition from practice to academia have been made. Although clinical expertise is essential for becoming a successful faculty member, it is insufficient by itself. New faculty members would benefit from faculty development programs that are customized to the school, faculty member, and job responsibilities, considering that each new faculty member has a different level of experience or knowledge in educating. Specific examples of a customized program include completing graduate education courses, attending interdisciplinary or interprofessional workshops, establishing a network of teaching support or mentors, and pursuing outside professional development options.

Based on a national survey of school of nursing deans, 5 essential skills for new nursing faculty members have been proposed. In order of importance, they are: teaching skills, knowledge/experience/preparation, curriculum/course development skills, evaluation and testing skills, and personal attributes. Of these 5 skills, teaching and personal attributes have been highlighted as applicable to new pharmacy faculty members. New faculty members often teach using the method in which they learn best, whether it be visual, auditory, or using other teaching methods. New faculty members need to appeal to an entire classroom of students with differing learning styles. Because professional pharmacy and graduate students are of high intellect, using active-learning skills and technology in the classroom can help these students get the most out of a class. The second important skill highlighted as useful for new faculty members is personal attributes. While there is no gold standard for how a faculty member should act, nursing literature has shown that faculty members who were enthusiastic, available, approachable, flexible, humorous, and respectful created strong relationships with students and a better learning environment. Conversely, faculty members who were inaccessible or who had poor communication skills or patience were associated with deficient learning environments and reduced student retention.

Engineering

Perhaps the most beneficial article found was from Education Designs and North Carolina State Department of Engineering that contained several key points that the profession can use in helping residents make the transition to faculty member.1 Colleges spend hundreds of thousands of dollars and significant time over the first several years on new faculty members. An inappropriate training and mentorship plan for new faculty members can be both costly and time consuming. Further, faculty members who get off to a slow start or have initial difficulty are also more likely to become disillusioned with academia and have less productive careers. The suggestions provided in this article are specific to new faculty members starting in engineering programs, but most of the recommendations can be extrapolated to new clinical pharmacy faculty members.

A strong recommendation from this article was to establish a new faculty development program. The authors believe this program should be held at the college level rather than university wide. University-wide orientation sessions generally focus on human resource or employment benefit education and are not specific to job requirements necessary for professional success. Eliminating university-wide orientation was not recommended because it is an effective way to disseminate universal policies and information. However, given that clinical faculty positions have specific job requirements, a specific orientation session is vitally necessary to ensure that faculty members begin their career with the correct goals and objectives. A survey of new pharmacy practice faculty members indicated they wanted additional orientation or instruction regarding teaching and scholarship.17

In order for a college-specific new faculty orientation to work, support from the college dean and department chair is essential. This support comes in the form of both financial and time commitments for the new faculty members and existing faculty mentors, coordinating facilities and guest speakers, and continued self-assessment and modification of the orientation program. The new faculty development workshop previously described received positive feedback from faculty members, with 89% of 111 participants rating it as excellent and 11% rating the orientation as good.2

A Blueprint for Transitioning Residents Into Successful Clinical Faculty

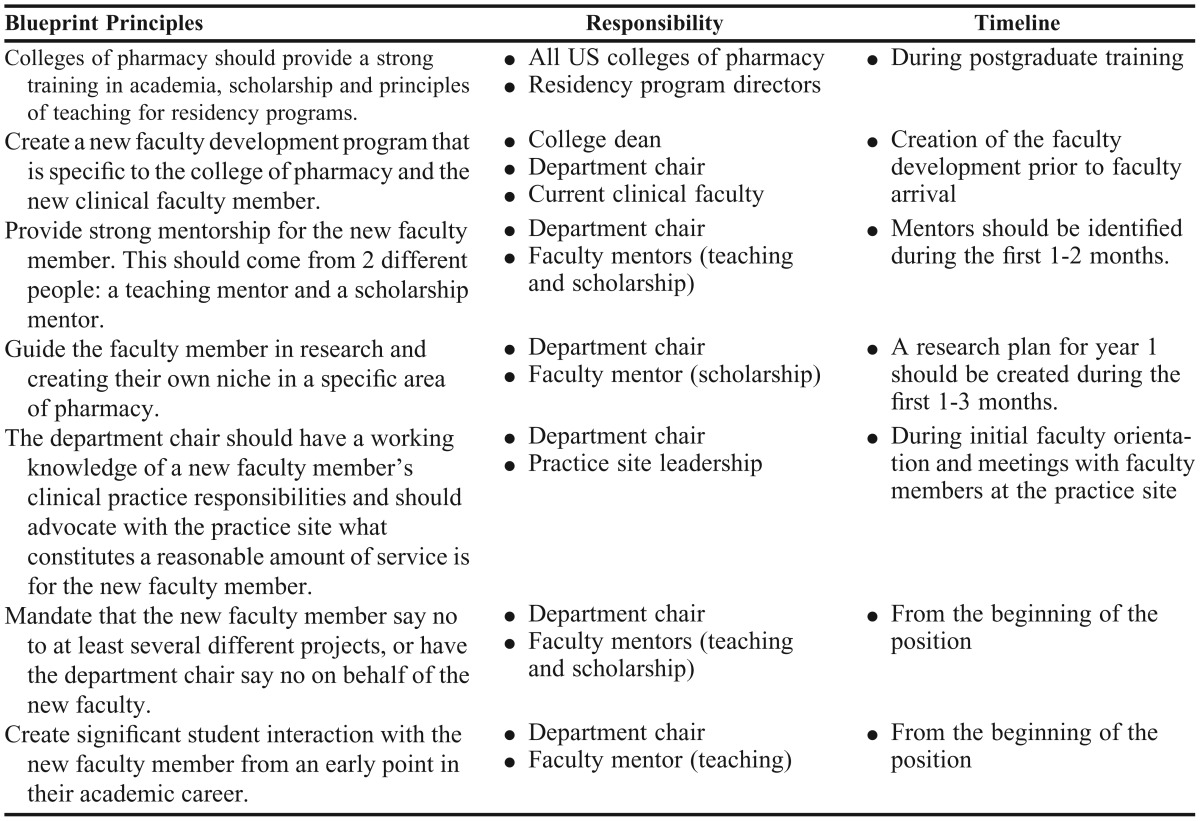

After reading and evaluating the various articles described above, we created 7 principles that we believe can facilitate the direct transition of pharmacy residents into successful clinical faculty members (Table 1). These principles are a combination of ideas from various articles in other disciplines regarding transitioning students or workers into successful faculty member roles. The principles also incorporate current practices at the University of Houston College of Pharmacy that have successfully worked for new clinical faculty members hired directly after completing their residencies.

Table 1.

A Starting Blueprint for Transitioning Residents Into Successful Clinical Faculty Members

The first 2 principles should occur either before or at the beginning of faculty employment. Colleges and schools of pharmacy should provide a strong training in academia, scholarship, and teaching principles for current residents. This responsibility falls on the various institutions to create a residency teaching program and on the residency program directors to provide the time and support for their residents to pursue this opportunity. For residents with a strong interest in pursuing a career in academia, an advanced track of training or additional academic responsibilities should be considered. Prior to hiring a resident into a faculty position, a new faculty development program or orientation that is specific to the college or school of pharmacy and the pharmacy practice department should be created. Internal faculty development programs should have the support of the dean and college leadership and be created and taught by current clinical faculty members who have roles similar to those of the new hire. Clinical faculty specific development programs can help new faculty members become more productive earlier on and provide an exciting starting point.

The scholarship component is often the most feared aspect of academia for new faculty members. They should have guidance from their department chair and scholarship mentor in creating a research plan early on that is both reasonable and interesting. A great example that our college has used is for new faculty members to publish a review article on a topic in which they are interested during their first year and, in year 2, to begin conducting research, building on previous scholarship. In addition to having a mentor in the area of scholarship, new faculty members should also have a different mentor for their teaching activities. Given that many faculty members excel in either teaching or scholarship, having separate mentors will help new faculty members benefit from the experience and guidance of successful academicians in both areas.

The department chair should establish a strong working relationship between the new faculty’s practice site and the leadership at that site. When initially meeting with leadership at a clinical practice site, the department chair should be present and advocate for the new faculty member regarding work expectations and responsibilities. A seasoned department chair has the knowledge of what has and has not worked for clinical faculty in the past and can use this knowledge to improve the chance of success for the new faculty member at that practice site. A strong and symbiotic relationship between the college and practice site leadership is crucial, especially for dual-funded positions. While it may be difficult for new faculty members to say no to ideas or recommendations from their practice site leaders, it may be especially difficult to say no to academic opportunities. Experienced faculty members often feel as though they cannot decline certain opportunities. Because the opportunity to collaborate or conduct research can be a form of flattery or prestige to new faculty members, they may find it difficult to say no to projects that are counterproductive for their careers. In the best interest of the new faculty member, department chairs may need to decline on behalf of the junior faculty member when the opportunity is not a good fit for the new faculty member’s research goals.

The last principle for transitioning residents into successful clinical faculty members is to create significant faculty-student interaction from an early point in their career. New faculty members are often siloed from students while they create lectures or courses. Providing new faculty members the opportunity to interact with students through student organizations or speaking at college meetings or events will help them establish the rapport with students that is essential for their success. These 7 principles, taken from the literature and experiences at our college may help residents transition directly into successful careers in academia.

CONCLUSION

With the abundance of clinical faculty positions available nationwide and the increased likelihood of current pharmacy residents transitioning from residency into academia, we must prepare our current residents to succeed in the role as a new clinical faculty members. Although there are several excellent references available for faculty development, there are no consensus guidelines for the specific transition of resident to faculty member that we commonly see in our profession. We hope this blueprint stimulates further discussion regarding how to help residents effectively transition into successful clinical faculty members.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beardsley R, Matzke GR, Rospond R, et al. Factors influencing the pharmacy faculty workforce. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 34. doi: 10.5688/aj720234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brent R, Felder RM, Rajala SA. 2006 Preparing new faculty members to be successful: a no-brainer and yet a radical concept. 2006 ASEE Conference, Washington, TC: ASEE . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slazak EM, Zurick GM. Practice-based learning experience to develop residents as clinical faculty members. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(13):1224–1227. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina HS, Herring HR. An advanced teaching certificate program for postgraduate year 2 residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2284–2286. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manasco KB, Bradley AM, Gomez TA. Survey of learning opportunities in academic for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2012;69(16):1410–1414. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNatty D, Cox CD, Seifert CF. Assessment of teaching experiences completed during accredited pharmacy residency programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 88. doi: 10.5688/aj710588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Teaching residents how to teach: a scholarship of teaching and learning certificate program (SLTC) for pharmacy residents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sylvia L. Mentoring prospective pharmacy practice faculty: a seminar series on teaching for pharmacy residents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2):Article 38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle CJ. Hiring residents as faculty members: dancing with the stars. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8):Article 143. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhower C. Residents perspective on the faculty hiring process. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(4):Article 85. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guglielmo BJ, Edwards DJ, Franks AS, et al. A Critical Appraisal of and Recommendations for Faculty Development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6):Article 122. doi: 10.5688/ajpe756122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlatic TD. Clinical Faculty Survival Guide, 1st edition. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Lenexa, KS. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jibson MD, Hilty DM, Alringhaus K, et al. Clinician-educator tracks for residents: three pilot programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):269–276. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.34.4.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz A, Thatcher J, Grover V. Making the transition from doctoral student to assistant professor. Decision Line (Doctoral Student Affairs). October 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aistrope D. The need for mentorship as residents move into the academy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 32b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penn BK, Wilson LD, Rosseter R. Transitioning from nursing practice to a teaching role. Online J Issues Nurs. 2008;13(3) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glover ML, Armayor GM. Expectations and orientation activities of first-year pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):Article 87. [Google Scholar]