Significance

A current key goal of HIV-1 vaccine development is to learn how to induce antibodies that will neutralize many diverse HIV-1 strains. Current HIV-1 vaccines elicit strain-specific neutralizing antibodies, whereas broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs) are not induced and only arise in select HIV-1 chronically infected individuals. One strategy for induction of favored antibody responses is to design and produce homogeneous immunogens with selective expression of BnAb but not dominant epitopes. In this study, we describe the binding properties of chemically synthesized variable loop 1/2 (V1V2) glycopeptides that bind both to mature HIV-1 envelope BnAbs and the receptors of their naïve B cells. These results demonstrate that such synthetic glycopeptides can be immunogens that selectively target BnAb naïve B cells.

Abstract

Current HIV-1 vaccines elicit strain-specific neutralizing antibodies. Broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs) are not induced by current vaccines, but are found in plasma in ∼20% of HIV-1–infected individuals after several years of infection. One strategy for induction of unfavored antibody responses is to produce homogeneous immunogens that selectively express BnAb epitopes but minimally express dominant strain-specific epitopes. Here we report that synthetic, homogeneously glycosylated peptides that bind avidly to variable loop 1/2 (V1V2) BnAbs PG9 and CH01 bind minimally to strain-specific neutralizing V2 antibodies that are targeted to the same envelope polypeptide site. Both oligomannose derivatization and conformational stabilization by disulfide-linked dimer formation of synthetic V1V2 peptides were required for strong binding of V1V2 BnAbs. An HIV-1 vaccine should target BnAb unmutated common ancestor (UCA) B-cell receptors of naïve B cells, but to date no HIV-1 envelope constructs have been found that bind to the UCA of V1V2 BnAb PG9. We demonstrate herein that V1V2 glycopeptide dimers bearing Man5GlcNAc2 glycan units bind with apparent nanomolar affinities to UCAs of V1V2 BnAbs PG9 and CH01 and with micromolar affinity to the UCA of a V2 strain-specific antibody. The higher-affinity binding of these V1V2 glycopeptides to BnAbs and their UCAs renders these glycopeptide constructs particularly attractive immunogens for targeting subdominant HIV-1 envelope V1V2-neutralizing antibody-producing B cells.

It is widely believed that a key characteristic of an effective HIV-1 vaccine would be its ability to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs). Known BnAbs have been shown to target conserved HIV-1 envelope (Env) regions including glycans, the glycoprotein 41 (gp41) membrane-proximal region, the gp120 variable loop 1/2 (V1V2), and the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) (1–7). Most mature BnAbs have one or more unusual features such as long heavy-chain third complementarity-determining regions, polyreactivity for non–HIV-1 antigens, and high levels of somatic mutations (2, 7, 8). In particular, CD4bs BnAbs have extremely high levels of somatic mutations, suggesting complex or prolonged maturation pathways (2–5). Adding to the challenge has been the difficulty in achieving binding of proposed antigens to germ-line or unmutated common ancestors (UCAs). Binding to BnAb UCAs would be a desirable characteristic for putative immunogens intended to induce BnAbs (5, 9–13).

Immunization of humans with Env proteins has not resulted in high plasma titers of BnAbs (14, 15). Rather, dominant strain-specific neutralizing epitopes have selectively been induced. This was most clearly seen in the ALVAC/AIDSVAX RV144 HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial, in which Env immunogens 92TH023 and A244 CRFAE_01 gp120s both expressed a dominant linear V2 epitope and bound with high-nanomolar affinity to the glycan-dependent V1V2 BnAbs PG9 and CH01 (16). Although both linear and glycan-dependent V2 epitopes were expressed on the A244 immunogen, the dominant V2 plasma antibody responses in this trial were targeted to linear V2 epitopes and not to the glycan-dependent BnAb epitope (14–16). A series of mAbs, the prototype of which is the mAb CH58, has been isolated from RV144 vaccines and shown to bind to linear V2 epitopes that include lysine 169 (16). However, they are strain-specific and only neutralize laboratory-adapted but not primary isolate HIV-1 strains (16). Although PG9 and CH01 V1V2 BnAbs also bind to V2 K169 and surrounding amino acids, they also bind to high-mannose glycans at N156 and N160 (17). Crystal structures of the CH58 antibody bound to V2 peptides demonstrated the V2 structure around K169 to be helical (16), whereas the crystal structure of the PG9 antibody with a V1V2 scaffold showed the same polypeptide region in a β-strand conformation (17).

The rationale that undergirded the studies described below envisioned that an optimal immunogen for the V1V2 BnAb peptide–glycan envelope region would be one that presented a chemically homogeneous entity that binds to V1V2 BnAbs with high affinity. In addition, an optimal immunogen for the V1V2 BnAb site would be one that binds with high affinity to V1V2 BnAb UCAs. Recently, in a preliminary disclosure, we described chemically synthesized glycopeptides of the HIV-1 Env V1V2 148–184 aa region with Man3GlcNAc2 or Man5GlcNAc2 glycan units at N156 and N160 (18). It was found that these homogeneous glycopeptide constructs with oligomannose units bound avidly to the V1V2 BnAb PG9. In this study, we report that the disulfide-linked dimeric forms of these glycopeptides bound preferentially to V1V2 BnAb mature antibodies (PG9 and CH01) over the V2 strain-specific mAb CH58, to which the binding was minimal. Importantly, the V1V2 peptide–glycans also bound to both PG9 and CH01 V1V2 BnAb UCAs, thus providing a strong rationale for their evaluation as experimental immunogens.

Results

Biophysical Characterization of Synthetic V1V2 Peptides.

The V1V2 glycopeptides were chemically synthesized as described previously (18) (Fig. S1). These glycopeptides included two glycans with either a terminal mannose3GlcNAc2 (Man3 V1V2) or a mannose5GlcNAc2 (Man5 V1V2) glycan at the two key N-linked glycosylation sites (Asn160 and Asn156) to which PG9 and CH01 V1V2 BnAbs bind (19, 23) (Fig. S1). Two additional V1V2 peptides, one with no glycans (aglycone V1V2) and a second with only the proximal GlcNAc2 units but with no outer mannose residues (GlcNAc2 V1V2), were used as controls (18). With these well-defined, biologically promising homogeneous compounds in hand, we came to wonder whether the thiol group at cysteine 157 in these constructs might play a role in their interactions with V1V2 BnAbs. Fortunately, it was not necessary to build a new construct, de novo, to ask this question. Rather, peptide 2 could be readily desulfurized, producing its alanine counterpart peptide 5 (Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cysteine-to-alanine mutation disrupted the active structure responsible for the binding characteristics and that the active structure was not as shown in peptide 1 but rather its oxidized cysteine dimer.

We initially observed that the synthetic V1V2 peptides could spontaneously undergo air oxidation and form disulfide-linked dimers. However, when solubilized in phosphate buffer, the V1V2 glycopeptides gave variable, batch-dependent binding results with the BnAbs PG9 and CH01, frequently showing weaker or no binding to the BnAbs and binding more strongly to the V2 mAb CH58 (Fig. S2). To determine whether dimer formation using alternative oxidation protocols might result in more consistent BnAb binding to V1V2 glycopeptides, we tested two different oxidizing agents: iodine and DMSO. The iodine-treated V1V2 Man3 glycopeptide bound to the V2 mAb CH58 but not to the BnAbs CH01 or PG9 (Fig. S2). Similarly, the iodine-oxidized Man5 glycopeptide showed no binding to CH01 and weak binding to PG9 but bound more strongly to CH58. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis showed that iodine treatment resulted in formation of higher-order oligomers and aggregates of the glycopeptides, thus suggesting that iodine treatment did not provide stable (i.e., unaggregated) dimer forms of the V1V2 glycopeptides.

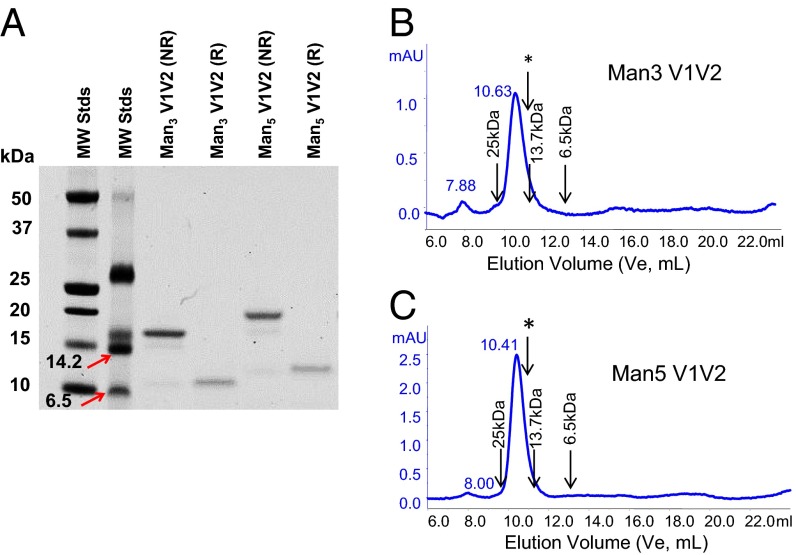

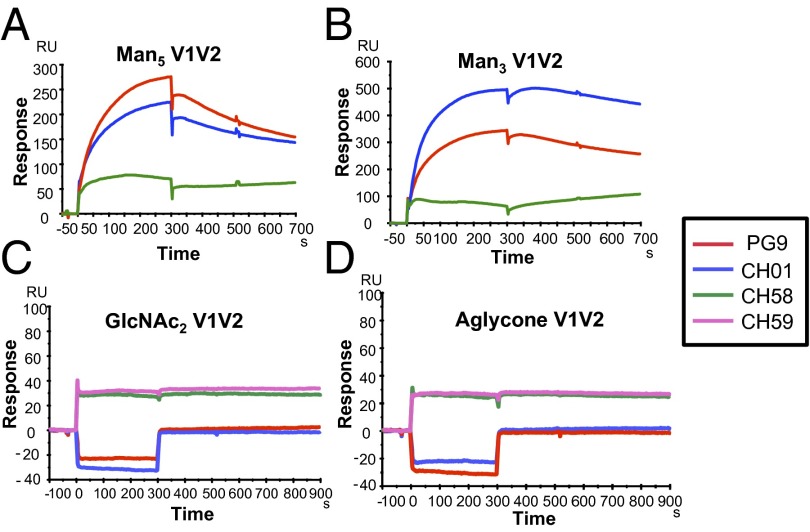

When solubilized in 20% (vol/vol) DMSO/phosphate buffer, the glycan-derivatized Man3 V1V2 and Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides were completely oxidized to disulfide-linked dimers (Fig. 1, Fig. S3, and Materials and Methods) (20). SDS/PAGE analysis of the DMSO-treated Man3 V1V2 and Man5 V1V2 peptides confirmed that the constructs had completely dimerized (Fig. 1A). Under reducing conditions, the dimers completely reverted to the monomeric state, consistent with a linkage via disulfide-bond formation (Fig. 1A). SEC analysis also showed that both Man3 V1V2 and Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides were dimeric by size, with no detectable monomeric forms or higher-order oligomers (Fig. 1 B and C), and therefore DMSO treatment provided stable unaggregated disulfide-linked dimer forms of the V1V2 glycopeptides. Most importantly, the differential binding of DMSO-oxidized glycopeptides to V1V2 BnAbs versus strain-specific V2 mAbs was reversed in favor of the BnAbs (Fig. 2). Following DMSO treatment, both Man5 and Man3 V1V2 glycopeptides bound more strongly to the BnAbs PG9 and CH01, whereas showing weak binding signal (even at the high peptide concentration of 50 μg/mL) to the V2 mAb CH58. By contrast, the binding of the V2 mAb CH58 was retained for the GlcNAc2 and aglycone V1V2 peptides, whereas no binding of the V1V2 BnAbs to either of the nonmannosylated V1V2 peptides was observed (Fig. 2 C and D). Thus, DMSO treatment of the V1V2 glycopeptides provided stable dimer formation and gave selective binding of the V1V2 peptides to the BnAbs PG9 and CH01 over the strain-specific V2 antibodies.

Fig. 1.

V1V2 glycopeptides form disulfide-linked dimers. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of V1V2 glycopeptides showing dimers under nonreducing and monomers under reducing conditions. Lanes from left to right are MW stds I, MW stds II (6.5, 14.2, 26.6 kDa), glycopeptides Man3 nonreduced, Man3 reduced, Man5 nonreduced, and Man5 reduced. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography of oxidized Man3 (B) and Man5 (C) -derivatized glycopeptides showing a single dimeric peak. Molecular masses of protein standards are marked. The elution volume (10.87 mL) of the Man3 C157A mutant, which does not form disulfide-linked dimers, is marked with an arrow and asterisk. mAU, milli absorbance units.

Fig. 2.

Selective binding of V1V2 BnAbs to mannose-derivatized V1V2 glycopeptides but not to aglycone or GlcNAc2 V1V2 peptides. SPR curves showing preferential binding of PG9 and CH01 BnAbs to Man5 (A) and Man3 (B) GlcNAc2 V1V2 glycopeptides but not to GlcNAc2 (C) and aglycone (D) peptides. By contrast, V2 mAbs CH58 and CH59 bound to both GlcNAc2 (C) and aglycone (D) V1V2 peptides. Each V1V2 peptide was oxidized by solubilization in DMSO and injected over the indicated mAb at 50 µg/mL. Data shown are after reference subtraction of nonspecific signal measured over the control mAb (Synagis). Binding data are representative of at least three experiments for Man5 and Man3 V1V2 peptides and two experiments for GlcNAc2 and aglycone V1V2.

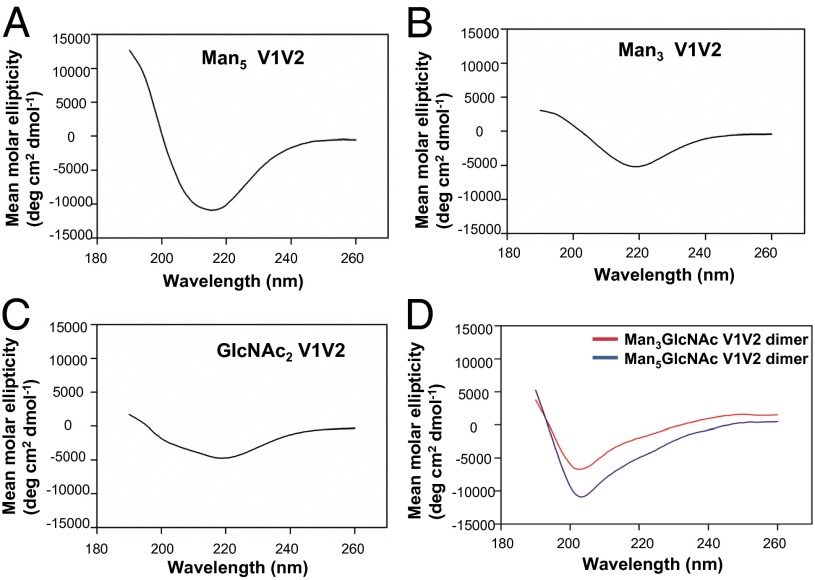

We next analyzed the biophysical properties of the synthetic V1V2 peptides by circular dichroism (CD) analysis to determine whether oxidative dimerization following DMSO treatment resulted in adoption of secondary structure by the V1V2 glycopeptides. CD spectral analysis showed that the V1V2 glycopeptides (with Man3 or Man5 glycans) adopted an ordered secondary structure, with spectra exhibiting a strong minimum at 218 nm and a maximum near 195 nm (Fig. 3 A and B), characteristics typically observed with peptides with β-sheet conformation (21). This β-sheet signature was reliably observed only when the glycopeptides had been treated with DMSO-containing buffer (the DMSO was removed before CD measurement; Materials and Methods). When exposed to aqueous buffer alone or when treated with iodine, the CD profile of the glycopeptides was dominated by a strong negative deflection around 200 nm (Fig. 3D and Fig. S4), which is consistent with predominant random-coil content (21). Similarly, the GlcNAc2-linked peptide displayed a more ordered CD spectrum after DMSO treatment, although the typical β-sheet features were less conspicuous relative to the spectra of the mannosylated glycopeptides (Fig. 3C). Poor aqueous solubility of the aglycone V1V2 peptide precluded CD analysis in phosphate buffer. Thus, the V1V2 peptides presented a more ordered structure in solution when treated with the oxidizing agent DMSO, suggesting the possibility that oxidation of the V1V2 peptides promoted disulfide linkage and contributed to the observed secondary structure with β-strand signature and the resulting selective binding of the V1V2 BnAbs.

Fig. 3.

Circular dichroism analyses of the secondary structure of the synthetic V1V2 peptides. V1V2 peptides derivatized with oligomannose units Man5 (A) or Man3 (B) GlcNAc2 V1V2 or only the proximal GlcNAc2-V1V2 (C) peptides show predominantly ordered secondary structure with β-strand and helical conformation. In D, Man3 and Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides were oxidized by iodine treatment and CD analysis was performed as above. CD spectra of each of the V1V2 peptides were taken at least two times. V1V2 peptides were solubilized in DMSO and allowed to fully dimerize in 20% DMSO/phosphate buffer for about 20 h. The CD spectrum deconvolution analysis (K2D3) of the Man5 glycopeptide gave an estimated 23% β-strand, Man3 V1V2 glycopeptide gave 33% β-strand, and GlcNAc2 V1V2 glycopeptide gave 17% β-strand.

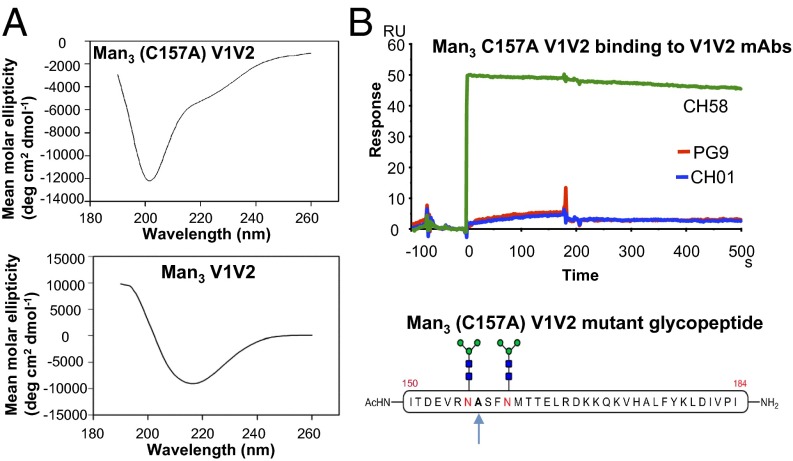

The formation of disulfide-linked dimers was due to the presence a lone Cys residue at position 157 of the V1V2 peptide (Fig. S1). Thus, the requirement of dimer formation of the glycopeptides for binding to the BnAbs was further investigated following mutation of Cys157 to Ala using a chemoselective desulfurization reaction (22). We observed that the secondary structure of the resulting mutant Man3 (C157A) V1V2 glycopeptide reverted to predominantly random-coil conformation (Fig. 4A) and resulted in the complete abrogation of the binding of the V1V2 BnAbs and promoted the binding of the V2 mAb CH58 (Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with earlier data showing the glycan dependence of binding of both V1V2 BnAbs (19, 23) and suggested that dimerization and β-sheet secondary structure of V1V2 glycopeptides are important for V1V2 BnAb recognition.

Fig. 4.

Circular dichroism secondary structure and antigenicity of C157A mutant Man3 V1V2 glycopeptide. (A) CD spectrum of C157A Man3 GlcNAc2 mutant showing glycopeptide in random-coil conformation and the lack of signature β-sheet features. (B) The CH58 mAb but not the V1V2 BnAbs (PG9 and CH01) bound to the C157A mutant V1V2 Man3 GlcNAc2 peptide (injected at 50 µg/mL). A second experiment in which Man3 C157A glycopeptide was initially solubilized in 20% DMSO (as described in Materials and Methods) gave similar binding to the CH58 mAb but not to either PG9 or CH01 V1V2 BnAbs.

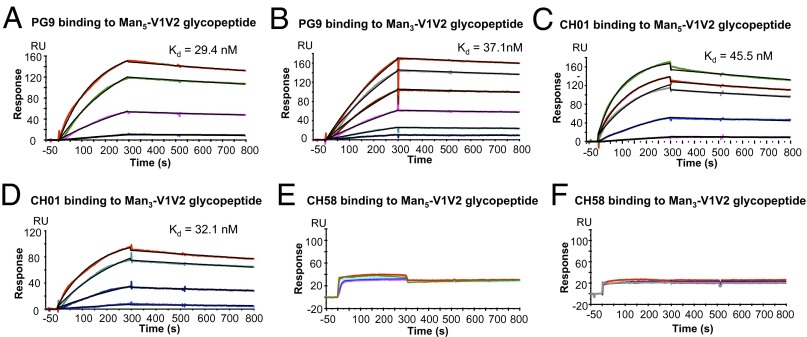

Antigenicity of V1V2 Peptides for Mature BnAbs.

Both V1V2 BnAbs PG9 (18) and CH01 bound only to the synthetic Man3 V1V2 and Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides and not to the aglycone or GlcNAc2 V1V2 glycopeptides (Fig. 2). The binding affinities of the V1V2 BnAbs PG9 and CH01 were measured using Man3 or Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides following complete oxidation in DMSO. The V1V2 BnAb PG9 bound to the fully oxidized Man5 and Man3 glycopeptides with Kd values of 29 and 37 nM, respectively (Fig. 5 A and B and Table S1). The CH01 BnAb also bound to Man5 and Man3 V1V2 glycopeptides with similar affinities (Kd 46 and 32 nM, respectively) (Fig. 5 C and D and Table S1). Whereas PG9 and CH01 bound to the Man3 V1V2 glycopeptide with similar affinities, the binding affinity of PG9 to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide was about twofold higher than that of CH01 mAb binding to the same peptide. Although detectable, the binding of CH58 to either the Man3 or Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide did not show a dose dependence, and therefore a Kd could not be reliably measured (Fig. 5 E and F). Thus, the synthetic V1V2 glycopeptides with high-mannose glycans (N160/N156) and with secondary structure stabilized by disulfide-linked dimer formation bound selectively and more avidly to both V1V2 BnAbs.

Fig. 5.

Surface plasmon resonance measurements of PG9 and CH01 BnAb binding to dimerized V1V2 glycopeptides. V1V2 BnAbs PG9 (A and B) and CH01 (C and D) binding to varying concentrations of Man5 GlcNAc2 (A and C) and Man3 GlcNAc2 V1V2 (B and D). CH58 mAb binding to Man5 GlcNAc2 (E) and Man3 GlcNAc2 (F). V1V2 glycopeptides were injected at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 µg/mL for PG9 and CH01, and from 1 to 50 µg/mL for the CH58 mAb. Data are representative of at least three measurements for PG9 and CH01 binding to either the Man5 or Man3 V1V2 glycopeptides. V1V2 peptides were solubilized in 20% DMSO overnight to allow complete dimer formation.

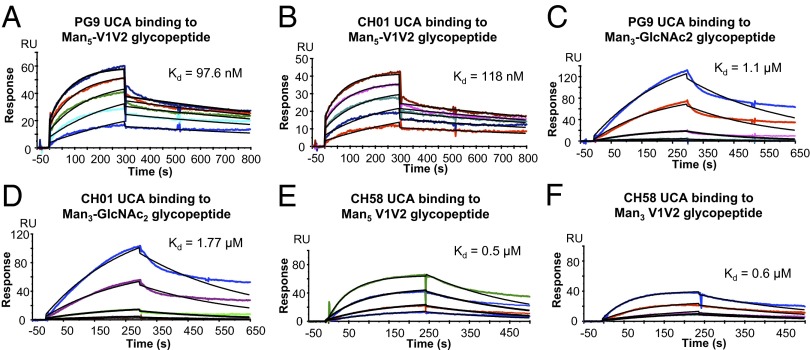

Binding of V1V2 Glycopeptides to BnAb Unmutated Common Ancestors.

A key characteristic of an immunogen is to not only bind to the mature BnAb but also to bind to the UCAs of the BnAbs that are predicted to be the receptors of the BnAb naïve B-cell precursors (8). Whereas gp120s have been found that bind the CH01 UCA at Kds of 300 nM to 1 µM (23, 24), no Env construct has been reported that binds to the PG9 UCA. Importantly, both the Man3 and Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides bound the UCAs of PG9 and CH01 (Fig. 6). The binding of both the PG9 UCA and CH01 UCA was an order of magnitude stronger to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide (Kd 98 and 118 nM to the PG9 UCA and CH01 UCA, respectively; Table S1) than the Man3-derivatized V1V2 glycopeptide (Kd = 1.1 and 1.8 µM to the PG9 UCA and CH01 UCA, respectively; Fig. 6 and Table S1). The binding of both the PG9 and CH01 UCAs gave biphasic dissociation rates, and the rate constant values of the faster component of the dissociation rates showed that both the PG9 UCA and CH01 UCA formed complexes with the Man5 V1V2 peptide that were more stable than those formed with the Man3 V1V2 glycopeptide (Table S1).

Fig. 6.

Binding of BnAb UCAs and the CH58 UCA to synthetic V1V2 glycopeptides. Man5 GlcNAc2 V1V2 glycopeptide at concentrations ranging from 2 to 25 µg/mL binding to the PG9 UCA (A) or CH01 UCA (B). Man3 GlcNAc2 V1V2 at concentrations ranging from 1 to 8 µg/mL binding to the PG9 UCA (C) or CH01 UCA (D). Man5 (E) and Man3 (F) glycopeptides were injected at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 µg/mL over the CH58 UCA captured on anti-IgG–immobilized surface as above. Both peptides were solubilized in 20% DMSO overnight to allow complete dimer formation as described in Materials and Methods.

Compared with the mature BnAbs, the binding of both the PG9 UCA and CH01 UCA to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptides was about threefold weaker, with the UCAs showing faster dissociation rates (Table S1). Glycopeptide binding of both the PG9 and CH01 UCAs required the presence of terminal high-mannose residues because neither UCA bound to either aglycone V1V2 or the GlcNAc2 V1V2 peptides. Whereas the PG9 and CH01 UCAs bound to the Man3 V1V2 glycopeptide equally as well as to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide, binding affinities of the PG9 and CH01 UCAs to Man3 was a log less compared with their binding to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide (Table S1). Thus, the UCAs specifically required Man5-derivatized V1V2 glycopeptides for optimal binding, whereas the mature antibodies did not.

In contrast to the mature strain-specific CH58 mAb, the CH58 UCA showed dose-dependent binding to the mannose-derivatized V1V2 glycopeptides (Fig. 6 E and F). The CH58 UCA bound to both V1V2 glycopeptides with Kd values of 0.5 and 0.6 µM for Man5 and Man3 V1V2, respectively. By contrast, the BnAb UCAs and the V2 CH58 UCA bound with similar and weaker affinities to Man3 V1V2, but the UCAs of both PG9 and CH01 bound to Man5 V1V2 with higher affinities (fivefold) than the UCA of CH58 (Fig. 6 and Table S1). Thus, Man5-derivatized V1V2 glycopeptides showed higher-affinity binding to the UCAs of the subdominant BnAbs than the UCA of the strain-specific vaccine-induced V2 mAb.

Discussion

In this study, we report a homogeneous synthetic HIV-1 Env V1V2 Man5 glycopeptide capable of binding with apparent nanomolar affinities to both mutated HIV-1 envelope V1V2 BnAbs and to their UCAs. A rational strategy for vaccine induction of BnAbs has been proposed to target the UCAs and intermediate antibodies of BnAb lineages (8, 9, 25). Key to this work is the availability of synthetically derived homogeneous immunogens that display only subdominant BnAb epitopes to maximize the opportunity for BnAb B cells to make a robust germinal center response in the absence of dominant competing strain-specific neutralizing B-cell lineages (8). The V1V2 Man5 glycopeptides preferentially bound with nanomolar Kds to the V1V2 BnAbs, including their UCAs. Our designed synthetic V1V2 glycopeptides exhibit enhanced expression of V1V2 BnAb epitopes by providing both homogeneous expression of the critical glycans and restricting the plasticity of the V1V2 peptide backbone to favor the epitope conformation recognized by V1V2 BnAbs over dominant strain-specific linear peptide epitopes.

It has previously been shown that the gp120 V1V2 region recombinant proteins can present multiple conformations to B cells, and V1V2 BnAbs and strain-specific mAbs may bind to conformationally distinct forms of V1V2 (16, 17). The plasticity of the V1V2 region and the heterogeneity associated with recombinantly produced proteins pose a challenge for vaccine design. Recombinantly produced gp120 proteins are prone to aberrant dimer formation that can mask subdominant BnAb epitopes (24, 26). Furthermore, differential glycosylation results in structural heterogeneity, including protein misfolding, that can exist in the gp120 protein and specialized V1V2-scaffold constructs. Thus, one factor in the inability of recombinantly produced Env proteins to induce BnAbs could be due to heterogeneous glycosylation and the suboptimal representation of the glycosylated molecular form that mirrors that of the native trimer. The precise conformation of the V1V2 BnAb epitopes in the context of the native Env trimer awaits determination. That V1V2 glycopeptides reported here bind with Kds in the nanomolar range suggests their conformational similarity to the epitope on the native Env trimer. Furthermore, the requirement of the adoption of β-strand conformation of the V1V2 glycopeptides for PG9 binding is consistent with the reported structure of PG9 binding to scaffolded V1V2 (17). However, the V1V2 described by McLellan et al. (17) consists of four antiparallel β-strands that are stabilized by a pair of interstrand disulfide bonds. The V1V2 glycopeptides described here are shorter in length (exclude the A- or D-strand sequences) and include a single Cys residue, allowing the peptides to form disulfide-linked dimers and thereby present a β-strand conformation. It would be of interest to determine whether the cationic β-conformation of the V2 C strand and the mannose glycans are positioned favorably in the glycopeptide dimer and thus account for the avid PG9 binding to the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide. Indeed, the question of how similar the V1V2 glycopeptide-bound complex is to the McLellan et al. scaffolded V1V2 can only be answered with more detailed structural data. Thus, structures of PG9 and/or CH01 with the Man5 V1V2 glycopeptide will be informative.

We could not detect binding of either PG9 or CH01 to Man3GlcNAc2 or Man5GlcNAc2 glycans in the absence of the V2 peptide backbone (18), suggesting that the binding to oligomannose glycans alone is very weak; this conclusion is consistent with the reported inability of the sugars themselves to inhibit V1V2 BnAb binding (10) and the 1.6 mM Kd of PG9 binding to Man5GlcNAc2Asn when measured using the more sensitive saturation transfer difference NMR technique (17). However, the peptide-linked oligomannose units are required for PG9 and CH01 BnAb binding when presented in the context of the V1V2 backbone. In addition, we found that disulfide-linked dimer formation was required for the V1V2 BnAbs but not for the V2 mAb CH58. The sensitivity of BnAb binding to Cys mutation suggests that the N160 and N156 glycans are perhaps spatially positioned more favorably in a dimer, thereby allowing for higher-avidity binding or recognition of glycans on two V1V2 units. Asymmetric binding to adjacent V1V2 elements has been proposed in a recent model (27) to explain the preferential binding of PG9 to Env trimers (28). We also found that the introduction of the Cys-to-Ala mutation resulted in the loss of the secondary structure of the Man3 glycopeptide. Our data demonstrate a clear role for the thiol of the Cys side chain in promoting/stabilizing the conformation of the glycopeptides via disulfide-linked dimer formation. Indeed, a known strategy for stabilization of designed β-sheet–forming peptides in aqueous solutions involves dimerization (face-to-face or edge-to-edge) and intermolecular disulfide linkage (29–33), so the observed secondary-structure preferences could very well be due to a similar phenomenon. In our case, the best results were obtained when the oxidative dimerization was performed in aqueous DMSO. The quantitatively dimerized constructs exhibited BnAb affinities that were significantly improved over our earlier results with glycopeptides that had not been deliberately treated with oxidizing agent (18). Interestingly, DMSO appears to play an additional role, because other oxidation protocols, such as treatment with iodine, resulted in material that was largely unstructured in solution and bound minimally to V1V2 BnAbs. It is possible that the DMSO cosolvent facilitates proper “folding” of the V1V2 constructs and mitigates against the known propensity of β-sheet polypeptides to aggregate in solution (34).

Short peptides generally exist in aqueous solution as an ensemble of conformations, although some sequences are known to display distinct secondary-structure preferences (35). From the standpoint of immunogen design, some means of rigidifying the V1V2 backbone to induce an intrinsic β-preference would be desirable for targeting the subdominant BnAb response. A seemingly straightforward strategy would involve cyclization using an intramolecular disulfide linkage (36). In this regard, Amin et al. recently reported the synthesis of monomeric cyclic V2 peptides with glycans at N160 and N156/N173 (37). Binding affinity of the cyclized peptide constructs for the BnAbs (PG9 and PG16 Fabs) was low in the micromolar range, binding to BnAb UCAs was not reported, and it is also unclear to what extent the peptides were structured because the solution conformations were not probed spectroscopically. Our results suggest a potentially more effective means to promote the desired conformation in V1V2 glycopeptides, namely via quarternary structure-level interactions involving homodimerization via intermolecular disulfide-bond formation.

Finally, for any peptide to be immunogenic, it will need the presence of T-helper cell determinant epitopes in the peptide design or have a T-helper determinant carrier protein conjugated to the V1V2 peptide. In this regard, it is important to note that at least two T-helper epitopes have been reported in the sequence of our V1V2 glycopeptides, one from amino acids 167–176 (38) and another at amino acids 172–184 (39).

Thus, use of chemically synthesized glycopeptides as described in this study can be a useful strategy for producing V1V2 constructs that preferentially bind to V1V2 BnAbs. Such constructs should serve as rationally designed immunogens for targeting B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibody lineages.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of V1V2 Peptides.

Design and chemical synthesis of the V1V2 peptides as single glycoforms were as described previously (18). Man3GlcNAc2 C157A mutant glycopeptide was synthesized and subjected to desulfurization (see procedure below). The aglycone and GlcNAc2 V1V2 were solubilized in DMSO at 5–10 mg/mL and then diluted in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with vortexing and brief sonication. For complete oxidation of the glycopeptides, Man3GlcNAc2 V1V2 and Man5GlcNAc2 V1V2 glycopeptides were solubilized in DMSO at 5–10 mg/mL and then diluted dropwise to 20% DMSO (in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) as above and left overnight at room temperature. The V1V2 glycopeptides were further diluted to the required concentration (1–50 µg/mL) for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding analyses in PBS (pH 7.4). Size-exclusion chromatography was performed on a Superdex Peptide 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in PBS buffer. Molecular mass of the V1V2 peptides was determined using protein standards ranging from 25 to 6.5 kDa.

SDS/PAGE analysis of the V1V2 peptides was done by solubilizing the glycopeptides (Man3, Man5) in 20% DMSO in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and incubating at room temperature overnight to allow dimer formation as described above. Reduced and nonreduced peptide samples, each at 5–10 µg, were heated in a hot water bath for 5 min before subjection to gel electrophoresis on a NuPage Novex 4–12% bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies) in 1× MES running buffer [50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.3] at 200 V for ∼45 min. The gel was stained and destained using a heated Coomassie blue protocol. Precision Plus All Blue Protein Standards (Bio-Rad) and Color Marker Ultra-low Range (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to lanes 1 and 2, respectively, for estimates of the peptides’ relative molecular masses.

Cysteine Desulfurization Procedure.

The buffer required for desulfurization was freshly prepared before the reaction. Na2HPO4 (56.6 mg, 0.4 mmol) was solubilized in water (1 mL), guanidine·HCl (1.146 g, 12 mmol) and Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl) (46 mg, 0.17 mmol) were then added, and the pH was brought to 7 with a solution of NaOH (5 M, 110 µL). After 15 min of degassing, the solution was ready for use. The glycopeptide (1 mg) was solubilized in 1 mL of buffer, and tert-butylthiol was added (30 µL, 0.34 mmol) followed by radical initiator VA-044 (Wako Chemicals) (0.1 M in water). The reaction mixture was stirred at 37 °C for 2 h. Upon completion, the glycopeptide was desalted by SEC [Bio-Gel P-6 (Bio-Rad), medium, acetonitrile/water (2:8, 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid)]. The crude peptide was purified to homogeneity by RP-HPLC (C8 semiprep, 20–45% acetonitrile/water over 30 min, 16 mL/min). Lyophilization of the collected fractions provided the desulfurized glycopeptide (500 µg) as a white solid.

Antibodies.

The isolation of the CH01 mAb from IgG+ memory B cells of a broad neutralizer subject has been previously described (23). The inference and production of unmutated ancestors of CH01 and PG9 were as described earlier (23, 40). V1V2 conformational/quaternary mAb PG9 was provided by Dennis Burton (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Synagis (palivizumab; MedImmune), a human respiratory syncytial mAb, was used as a negative control.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Measurements.

V1V2 glycopeptide-binding Kd and rate-constant measurements were carried out on BIAcore 3000 instruments (GE Healthcare) as described earlier (41, 42). Anti-human IgG Fc antibody (Sigma Chemicals) was immobilized on either a CM3 or CM5 (CM3 for kinetics and Kd determination) sensor chip (to minimize nonspecific binding of peptides to the chip matrix) to about 5,000 resonance units (RUs), and each antibody was captured to about 100–200 RU on individual flow cells in addition to one flow cell with the control Synagis mAb on the same sensor chip. Nonspecific binding of the V1V2 glycopeptide was double-referenced by subtracting the control surface and blank buffer flow for each mAb–V1V2 glycopeptide binding interaction. For rate constants and Kd measurements, each V1V2 peptide was solubilized in 20% DMSO/phosphate buffer and allowed to oxidize to completion (20-h incubation) and then diluted in phosphate buffer and injected at 50 µL/min at concentrations ranging from 1 to 40 µg/mL. SPR curve-fitting analysis was performed using a global fit of multiple titrations to the 1:1 Langmuir model. All data analysis was performed using BIAevaluation 4.1 analysis software (GE Healthcare).

Circular Dichroism Analysis of V1V2 Peptides.

Circular dichroism spectra of V1V2 peptides were measured on an Aviv model 202 spectropolarimeter using a 1-mm path-length quartz cuvette. The 20% DMSO-treated peptides were dialyzed against 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to remove DMSO using a dialysis cassette of molecular mass cutoff 3,500 Da. CD spectra of peptides (at 100–200 µg/mL concentration) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) were recorded at 25 °C. Three scans of the CD spectra of each peptide were averaged, and the CD signal from phosphate buffer was subtracted out.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Hieu Nguyen (Duke Human Vaccine Institute) for SDS/PAGE analysis of V1V2 peptides, and Kim McClammy for secretarial assistance. This work was funded by Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology (CHAVI) [Division of AIDS (DAIDS), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH)] Grant AI0678501; Duke Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology-Immunogen Discovery (CHAVI-ID) (DAIDS, NIAID, NIH) Grant UM1-AI100645; and a Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery Grant (OPP1033098; to B.F.H.) from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. P.K.P. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (PF-11-014-01-CDD) from the American Cancer Society. A.F.-T. thanks the European Commission (Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship) for financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1317855110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science. 2012;337(6091):183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1225416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: Identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity. 2012;37(3):412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu X, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329(5993):856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu X, et al. NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science. 2011;333(6049):1593–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheid JF, et al. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science. 2011;333(6049):1633–1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sattentau QJ, McMichael AJ. New templates for HIV-1 antibody-based vaccine design. F1000 Biol Reports. 2010;2:60. doi: 10.3410/B2-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascola JR, Haynes BF. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: Understanding nature’s pathways. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):225–244. doi: 10.1111/imr.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, et al. All known cross reactive HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies are highly divergent from germline and their elicitation may require prolonged periods of time. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doores KJ, Burton DR. Variable loop glycan dependency of the broad and potent HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies PG9 and PG16. J Virol. 2010;84(20):10510–10521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00552-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma BJ, et al. Envelope deglycosylation enhances antigenicity of HIV-1 gp41 epitopes for both broad neutralizing antibodies and their unmutated ancestor antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pancera M, et al. Crystal structure of PG16 and chimeric dissection with somatically related PG9: Structure-function analysis of two quaternary-specific antibodies that effectively neutralize HIV-1. J Virol. 2010;84(16):8098–8110. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00966-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao X, et al. Germline-like predecessors of broadly neutralizing antibodies lack measurable binding to HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: Implications for evasion of immune responses and design of vaccine immunogens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390(3):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes BF, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1275–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montefiori DC, et al. Magnitude and breadth of the neutralizing antibody response in the RV144 and Vax003 HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(3):431–441. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao HX, et al. Vaccine induction of antibodies against a structurally heterogeneous site of immune pressure within HIV-1 envelope protein variable regions 1 and 2. Immunity. 2013;38(1):176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLellan JS, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature. 2011;480(7377):336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aussedat B, et al. Chemical synthesis of highly congested gp120 V1V2 N-glycopeptide antigens for potential HIV-1-directed vaccines. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(35):13113–13120. doi: 10.1021/ja405990z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LM, et al. Protocol G Principal Investigators Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326(5950):285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam JP, Wu C-R, Liu W, Zhong JW. Disulfide bond formation in peptides by dimethyl sulfoxide. Scope and application. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113(17):6657–6662. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield NJ. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(6):2876–2890. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wan Q, Danishefsky SJ. Free-radical-based, specific desulfurization of cysteine: A powerful advance in the synthesis of polypeptides and glycopolypeptides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(48):9248–9252. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonsignori M, et al. Analysis of a clonal lineage of HIV-1 envelope V2/V3 conformational epitope-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies and their inferred unmutated common ancestors. J Virol. 2011;85(19):9998–10009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam SM, et al. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of RV144 vaccine AIDSVAX clade E envelope immunogen is enhanced by a gp120 N-terminal deletion. J Virol. 2013;87(3):1554–1568. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00718-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimitrov DS. Therapeutic antibodies, vaccines and antibodyomes. MAbs. 2010;2(3):347–356. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finzi A, et al. Conformational characterization of aberrant disulfide-linked HIV-1 gp120 dimers secreted from overexpressing cells. J Virol Methods. 2010;168(1-2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Julien JP, et al. Asymmetric recognition of the HIV-1 trimer by broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(11):4351–4356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217537110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker LM, et al. Protocol G Principal Investigators Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477(7365):466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khakshoor O, Nowick JS. Use of disulfide “staples” to stabilize β-sheet quaternary structure. Org Lett. 2009;11(14):3000–3003. doi: 10.1021/ol901015a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn TP, Tweedy NB, Williams RW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Betadoublet: De novo design, synthesis, and characterization of a beta-sandwich protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(19):8747–8751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatraman J, Nagana Gowda GA, Balaram P. Design and construction of an open multistranded beta-sheet polypeptide stabilized by a disulfide bridge. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(18):4987–4994. doi: 10.1021/ja0174276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan Y, Erickson BW. Engineering of betabellin 14D: Disulfide-induced folding of a beta-sheet protein. Protein Sci. 1994;3(7):1069–1073. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayo KH, Ilyina E, Park H. A recipe for designing water-soluble, beta-sheet-forming peptides. Protein Sci. 1996;5(7):1301–1315. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nesloney CL, Kelly JW. Progress towards understanding β-sheet structure. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4(6):739–766. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Defining solution conformations of small linear peptides. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1991;20:519–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santiveri CM, León E, Rico M, Jiménez MA. Context-dependence of the contribution of disulfide bonds to beta-hairpin stability. Chemistry. 2008;14(2):488–499. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amin MN, et al. Synthetic glycopeptides reveal the glycan specificity of HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(8):521–526. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steers NJ, et al. HIV-1 envelope resistance to proteasomal cleavage: Implications for vaccine induced immune responses. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Souza MS, et al. Ministry of Public Health–Thai AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group Collaborators The Thai phase III trial (RV144) vaccine regimen induces T cell responses that preferentially target epitopes within the V2 region of HIV-1 envelope. J Immunol. 2012;188(10):5166–5176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munshaw S, Kepler TB. SoDA2: A Hidden Markov Model approach for identification of immunoglobulin rearrangements. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(7):867–872. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam SM, et al. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J Immunol. 2007;178(7):4424–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alam SM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 antibodies that mask membrane proximal region epitopes: Antibody binding kinetics, induction, and potential for regulation in acute infection. J Virol. 2008;82(1):115–125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00927-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.