Tunable p-n heterojunction diodes

False-colored scanning electron micrograph of a carbon nanotube/MoS2 heterojunction diode.

The p-n junction diode, a ubiquitous building block of modern electronics, has numerous applications ranging from integrated circuits to photovoltaics and lasers. However, the recent emergence of extremely thin materials suggests that this integral electronic component can be scaled down to thicknesses of a few atoms, potentially enhancing its functionality even further. Deep Jariwala et al. (pp. 18076–18080) demonstrate the fabrication and operation of a p-n heterojunction diode—an interface that passes current between dissimilar semiconductor types—based on atomically thin molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and sorted semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs). The electrical characteristics of these heterojunction diodes can be precisely tuned to achieve behavior ranging from insulating to rectifying. Furthermore, the diodes respond strongly to optical irradiation with a fast photoresponse and quantum efficiency that compares favorably with other recently reported atomically thin nanomaterials. By combining the highly desirable electrical properties of SWCNTs with the rapidly expanding field of atomically thin materials, the authors report, the p-n heterojunction concept might lead to a new generation of ultrathin, high-performance electronics and optoelectronics. — T. J.

Effects of early-childhood stress on behavior and brain development

Early-childhood stress, such as the disorganized care received by children reared in some orphanages, has been linked to psycho-pathology later in life but the neurobiological underpinnings of these outcomes remain unclear. Matthew Malter Cohen et al. (pp. 18274–18278) studied 16 orphanage-reared children, ages 11 and younger, and a group of 10 children who had not lived in orphanages. To account for the genetic and environmental factors that influence human studies, the authors mimicked the impoverished caregiving provided by the children’s orphanages in preweaned mice by decreasing nesting material available to the dams for a limited time. The findings uncover lasting effects of early life experiences on human behavior and development, the authors report. Early-onset and long lasting changes in anxious behavior and amygdala function were observed in mice exposed to disorganized parental care early in life, mirroring the heightened emotional reactivity and amygdala changes in orphanage-reared children. The changes persisted long after the children were removed from the stressor, and did not diminish with the development of prefrontal regulatory regions in the brain. According to the authors, the findings highlight how early-life stress can lead to altered brain circuitry and emotional dysregulation, and suggest that such children may benefit from early intervention. — A.G.

Maternal bond might influence bonobo social competence

One juvenile embraces another after the other loses a fight.

Previous studies have suggested that social skills, such as expressing sympathy and responding to others’ distress, are positively tied to emotion control in humans. Zanna Clay and Frans de Waal (pp. 18121–18126) examined the development of social and emotional competence in our close primate relatives: bonobos (Pan paniscus). The authors studied a range of social skills, including the apes’ abilities to sustain social interaction through play bouts, overcome self-distress, and console distressed peers through comforting acts such as touching, stroking, kissing, and embracing, among a group of juvenile bonobos in a forested sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Whereas some bonobos were born and mother-reared at the sanctuary, most arrived as orphans rescued in the wild from illegal bush-meat and pet trades and were rehabilitated at the sanctuary using surrogate human mothers. The authors report that juvenile bonobos who were more effective than others at coping with their own distress, as determined, for example, by how often and long they screamed after losing a fight, were also more adept at consoling others in distress triggered by conflicts. Further, such consoling behavior, the authors report, was more common among mother-reared bonobos than among orphans, suggesting the significance of the bond between mothers and offspring in shaping socio-emotional competence; mother-reared bonobos also recovered more quickly from their own distress, and were more socially competent and less anxious than orphans. According to the authors, the findings help illuminate the social and emotional development of bonobos. — P.N.

Synthetic, dopamine-triggered implant for blood pressure control

Pleasurable stimuli such as food, drugs, and sex trigger the brain to release the neurotransmitter dopamine, which leaks into the bloodstream via peripheral nerves. To investigate the relationship between the levels of dopamine in the blood and general circulation, Katrin Rössger et al. (pp. 18150–18155) reprogrammed a human cell line to produce a readily identifiable protein known as SEAP upon exposure to dopamine. After characterizing the cells’ response to dopamine in vitro, the authors placed the cells inside semipermeable microcapsules and implanted them into mice. Upon exposure to stimuli that trigger the release of dopamine, including food, methamphetamine, or sexual arousal, mice bearing the implant displayed elevated levels of SEAP in the circulation. To demonstrate the therapeutic potential of the device, the authors reengineered the cells to produce atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a blood pressure-lowering compound, in response to dopamine exposure and injected the implant into male mice with high blood pressure. When housed in the presence of a female mouse, which triggered sexual arousal, the animals with the implant displayed increased levels of ANP in the circulation and reduced blood pressure. The findings may aid the development of therapeutic devices controlled by automatic, subconscious physiological activities, according to the authors. — N.Z.

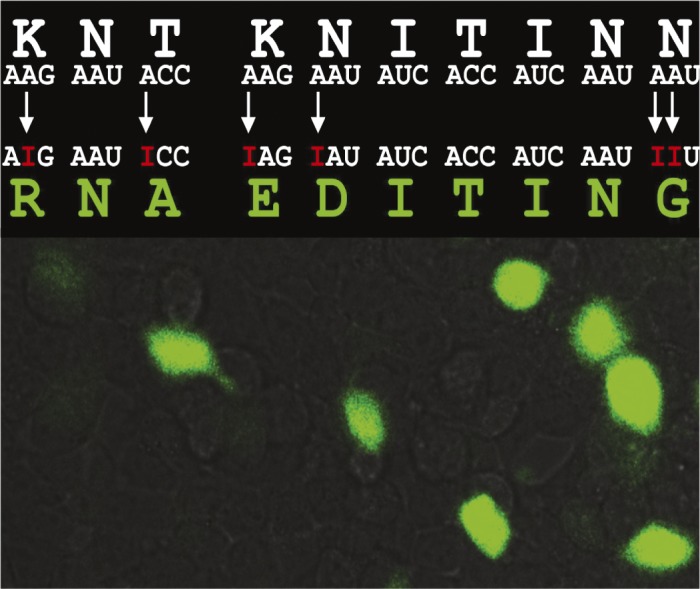

Synthetic “editase” performs RNA editing in human cells

Targeted correction by RNA editing.

Many organisms purposefully mutate newly transcribed genetic material via a natural process known as RNA editing by adenosine deamination. In this process, enzymes known as adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADARs) convert adenosine residues to inosines, which are read as guanosine during the translation of RNA to protein—a modification that ultimately changes the protein’s function. Maria Fernanda Montiel-Gonzalez et al. (pp. 18285–18290) unveil an engineered RNA editing enzyme that can selectively target editing to a single adenosine residue within the RNA registry. The authors crafted the enzyme, dubbed “editase,” by removing the endogenous targeting domains from human ADAR2 and replacing them with an antisense RNA oligonucleotide. The enzyme’s use was demonstrated in frog oocytes by successfully correcting a pre-mature stop codon in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator anion channel, and reestablishing functional chloride currents across the plasma membrane. Further exploration revealed that the editase could be fully encoded in genetic material to perform site-directed RNA editing in human cells, the authors report. The technology could spearhead powerful approaches to correct a wide variety of genetic mutations, and to fine tune protein function through targeted nucleotide deamination, according to the authors. — A.G.

Restoring a sense of touch with prosthetics

Sensory input from tactile receptors is critical to our ability to manipulate objects without dropping or crushing them, to embody our limbs, and to communicate emotion through touch. Gregg Tabot et al. (pp. 18279–18284) examined a technique to restore a sense of touch to people who are paralyzed or have undergone an amputation. In three rhesus monkeys, the authors used intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of primary somatosensory cortex (S1) to convey sensory information critical for object manipulation, including information about contact pressure, location, and timing. The authors trained the monkeys to perform a tactile discrimination task: judging where an object touched their hand. The authors then demonstrated that the animals could perform the task when some of the actual touches were replaced with ICMS. Finally, the authors compared the animals’ ability to perceive pressure when objects touched their real fingers or a prosthetic finger that delivered ICMS to S1. The animals performed equally well in both situations, suggesting that the prosthetic finger provided as much information about pressure as does the native one. The findings may represent a blueprint for using ICMS to restore touch to people who have lost it, according to the authors. — B.A.