Abstract

The repair of DNA damage is essential for the prevention of disease. The DNA double-strand break (DSB) is a particularly hazardous lesion. DNA DSBs activate a coordinated cellular response involving cell cycle checkpoint activation and repair of the DNA break, or alternatively apoptosis. In the nervous system the inability to respond to DNA DSBs may lead to neurodegenerative disease or brain tumors. Therefore, understanding the DNA DSB response mechanism in the nervous system is of high importance for developing new treatments for neurodegeneration and cancer. In this regard, the use of mouse models represents an important approach for advancing our understanding of the biology of the DNA damage response in the nervous system.

Keywords: DNA repair, double strand breaks, homologous recombination, non-homologous end-joining, neurodegeneration, nervous system

Introduction

The human brain contains on the order of one hundred billion neurons that support a broad range of functions throughout neural tissue [1]. A process critical for maintaining homeostasis in the brain is an effective response to DNA damage. A variety of diseases result from defective DNA repair and many of these show pronounced neuropathology [2–4]. In many cases the syndromes associated with DNA repair defects impact developmentally, as the formation of the nervous system strictly requires the ability to respond to DNA damage in proliferating and immature neural tissue. However, many neurodegenerative diseases linked to DNA repair deficiency show surprisingly select effects within the CNS, indicating that the consequences of DNA damage vary considerably depending on the nature of the DNA damage signaling pathways that are perturbed [5,6].

Because DNA repair deficiency can impact so substantially upon the nervous system, there is a need to produce model systems with which we can understand the pathways and etiological agents that are important for maintaining neural homeostasis. In this regard, the mouse offers an important resource for analysis of the effects of genotoxic stress during both the development and maintenance of the nervous system. Moreover, links are also emerging between DNA damage and significant neurological diseases associated with aging such as Alzheimer's disease [7,8]. Therefore, generation of model systems to understand the tissue-specific importance of DNA repair will also be valuable aids for refining therapeutic intervention of neurological disease. In the following we will emphasize the contribution mouse models have made towards understanding the biology of DNA repair in the nervous system.

Development of the nervous system

The nervous system presents a substantial challenge for delineating the requirements for DNA DSB repair, both embryonically and in the mature nervous system. In the mouse, the nervous system initiates its development onwards from around embryonic day 11 (E11) until three weeks after birth. Nervous system development follows a reiterated pattern of proliferation, differentiation and migration and finally maturation [9]. Proliferation occurs in the neuroepithelium (ventricular zone: VZ) that contains neural stem and progenitor cells. Post-mitotic cells migrate through the sub ventricular zone (SVZ) to their final programmed destination where they will undergo maturation. Detailed reviews are available that summarize many aspects of neural development [10–14].

Rapid proliferation drives development throughout the nervous system, and this process is linked to concomitant maturation of many diverse neural regions [15]. Although the bulk of cells in the nervous system are either neurons or glia, within these broad classes are a myriad of specialized cell types, which are characterized by specific functional roles they play to support the divergent functions of neural tissue. These cellular subgroups are characterized by their morphology, the neurotransmitters used for cellular communications and the connections they form with other cells. For example, the retina is a relatively small (but important) part of the nervous system which contains over 55 different cell types [16], and during development the spinal cord generates a diverse set of functionally different cell types [17]. This complexity is reiterated through out the nervous system, and the diversity in cell types potentially impacts the specific requirements for DNA repair pathways. An additional consideration for DNA repair in the nervous system is the contrasting requirement for this process during development and maturation, as the genesis of the complexity in the nervous system results from widespread zones of proliferation that ultimately generate the diversity in the nervous system. With regard to DNA DSBs, the repair pathways that are required will be a function of the proliferative state of the tissue. A major DSB repair pathway, homologous recombination (see later) requires a sister-chromatid for error-free repair, and therefore operates in replicating cells [18,19]. Thus, at this stage faulty DNA repair could lead to expansion of mutant progenitors, which could contribute to disease later in the mature nervous system. In non-replicating cells, which is the case for the mature nervous system DNA DSBs are repaired by an alternate pathway, non-homologous end-joining ([20]; see later). While the mature nervous system is largely non-replicating, there are nonetheless regions in which ongoing proliferation and neurogenesis occurs. However, this neurogenesis is very restricted and is confined to only the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, and overall is a minor component of proliferation in the mature brain [21–24]. Additionally, under some circumstances, such as disease or brain injury, limited glial cell proliferation may occur in the mature nervous system [25–27]. Recent advances in mouse genetics have allowed significant progress in our understanding of DNA repair in the nervous system. Below, we will outline the basic schema for the repair of DNA DSBs and illustrate the utility mouse models have played in deciphering the role of the DNA damage response in a tissue-specific setting. The utility of mouse systems for studying the role of nucleotide excision repair (NER) in the nervous system is described elsewhere in this volume, in a contribution from Laura Niedernhofer.

DNA DSB repair and mouse brain development

DNA DSBs initiate a signaling cascade that leads to the repair and resolution of the break or apoptosis. In the developing nervous system, apoptosis seems to be a common outcome after DNA DSBs (Figure 1) and may be a preferred strategy, as cells can be easily replaced from the abundant progenitor population present during neural development [28]. Basic strategies for repair of DSBs involve either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination repair (HR). These two major repair pathways maintain the integrity of DNA after endogenous DSBs or those arising from exogenous agents. Inactivation of either NHEJ or HR results in marked defects in nervous system development [28]. HR is an error-free process that uses a sister chromatid as template DNA to achieve precise repair [18,19,29]. Homology-directed repair initially involves DSB processing via Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) in collaboration with CtIP to generate 3' single stranded DNA that becomes bound by Rad51 to facilitate homology search and strand invasion [30–32]. The Rad51 recombinase functions in concert with a series of other factors including the Rad51 paralogs (Xrcc2, Xrcc3, RAD51L1, RAD51L2, RAD51L3), Rad52, and Rad54 proteins to promote strand invasion and subsequent recombinational repair [18,19,33–35].

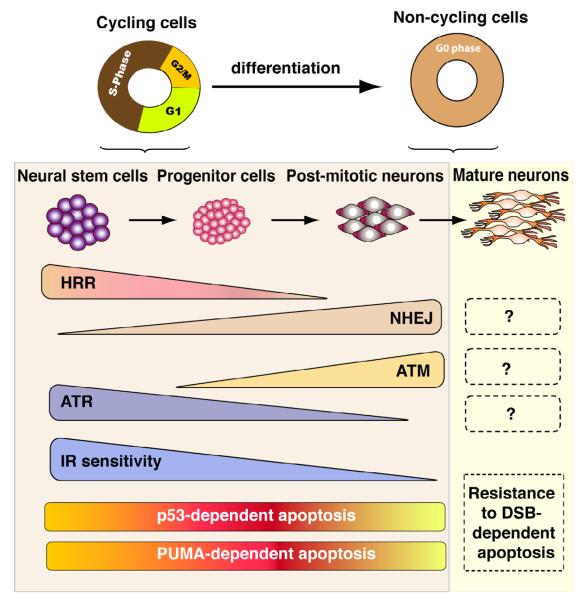

Figure 1. DSB responses are linked to developmental stage in the central nervous system.

The nervous system undergoes differentiation that follows a recurring pattern of proliferation (neural stem cells and progenitors), differentiation (post-mitotic neurons) and finally maturation. The differentiation status of neural cells determines the response to DNA damage and the repair and effector kinase that are activated. Proliferating cells use HR while NHEJ is the main repair pathways used by non-dividing cells. ATM appears to function in recently postmitotic neural cells, while ATR is required by proliferating cells. However, the functional overlap between these related kinases has yet to be fully elucidated. Both proliferating cells and immature, post-mitotic neural cells are highly susceptible to DNA damage induced apoptosis and this process requires the p53-Puma signaling pathway. Functionally important DNA repair or DNA damage signaling pathways, including those involving ATM/ATR, and in the mature nervous system are yet to be clearly defined.

In contrast to HR, NHEJ modifies the two DNA ends so that they are compatible for direct ligation and is the predominant pathway for repairing DSBs in non-cycling mammalian cells [20,36,37]. NHEJ is an error-prone DSB repair mechanism involving the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) and the DNA ligase IV (Lig4), which together facilitate re-joining of broken non-compatible DNA ends. The DNA-PK complex contains Ku70 and Ku80 proteins, which recognize the break and mediate recruitment of the DNA-PK catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), a protein kinase required for efficient NHEJ [36–38]. Ligation of the DNA ends occurs via Lig4 in conjunction with its binding partner Xrcc4. An additional factor, Cernunnos/XLF, has been identified as a binding partner of the Lig4-Xrcc4 complex and appears to be necessary for efficient ligation via NHEJ [39,40]. Subsets of NHEJ may involve other factors such as Artemis [41,42]. The choice of repair pathway that becomes activated is linked to the cell cycle, with HR being available in S- and G2-phases [43].

All components of the general DSB response machinery are present in the developing brain, although some reports suggest decreased activity of repair proteins are associated with ageing [44]. Inactivation of DNA repair genes in the mouse has been done extensively, and most known key repair factors have been targeted in the mouse [45]. In many cases, the inactivation of these factors is incompatible with viability and results in embryonic lethality. Nonetheless, DNA repair defective mice have provided many important insights about the interconnections between this particular DNA repair pathway and neural development. A key feature of DSB repair pathways in the developing nervous system is the requirement for HR in the proliferative zones in the nervous system, while NHEJ is important in the differentiating SVZ [46], although there can be significant cooperativity between these pathways [47,48]. Therefore, the DNA damage response will be related to specific developmental stages, with a limited repertoire being available in mature differentiated cells.

The role of NHEJ during mouse brain development

The core NHEJ components have all been subject to gene targeting in the mouse, and extensive phenotypic analysis has been undertaken in the resultant mutant nervous system [46,49–53]. Notably, inactivation of either Lig4 or Xrcc4 results in an identical lethal phenotype around midgestation, while inactivation of the DNA-PK complex components results in viable mutant animals [54]. Artemis-null animals are also viable, and while Xlf targeted ES cells are hypersensitive to DNA DSBs, Xlf-null mice have not yet been reported [55–57]. These differences in viability illustrate the relative dispensability of the NHEJ core components, and point to the critical requirement for Lig4 in preventing the accumulation of DSBs.

Disruption of either Lig4 or Xrcc4 in mouse leads to widespread neural apoptosis that occurs throughout the developing nervous system and is associated with regions containing immature postmitotic cells [49–51]. In the case of Lig4 (and presumably Xrcc4) there is no clear deficit in the mutant embryos until around E12, a time that coincides with regional differentiation in the nervous system, suggesting that NHEJ is relatively dispensable until neural differentiation commences [46]. This probably indicates that in the non-dividing neural cells active NHEJ is required for DNA DSB repair, and that other repair pathways cannot effectively substitute. The increased neural apoptosis after NHEJ loss has been suggested to involve oxygen metabolism that generates endogenous DSBs at a higher frequency than in other organs [58]. In Xrcc4 or Lig4-null mice, neural apoptosis and lethality is rescued by coincident inactivation of p53 [50,59]. In both cases double null animals succumb to lymphoma or medulloblastoma [50,59–61]. The occurrence of medulloblastoma (a brain tumour originating in the cerebellum) after inactivation of NHEJ probably reflects the importance for DNA DSB repair in the developing cerebellum. This organ continues to undergo substantial postnatal neurogenesis, and during this period of cerebellar growth produces granule neurons that will become the most abundant neuronal population in the brain [12,60].

Consistent with the need for effective repair of DNA DSBs by NHEJ, individuals with mutations in LIG4 exhibit immunodeficiency, developmental delay, growth retardation, and microcephaly, a disease that has been termed LIG4 syndrome (Table 1) [62,63]. Since knockout mice lacking functional Lig4 are not viable, the mutations in the LIG4 syndrome patients are hypomorphic alleles. In view of the neuronal apoptosis in Lig4-deficient mice, it is possible that LIG4 syndrome patients also experience elevated neuronal apoptosis during development, which could underlie the reported microcephaly and developmental delay (Figure 2).

Table 1.

DNA DSB repair diseases with neurological features in human.

| Syndrome | Gene | Neurological features |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Ataxia-Telangiectasia (A-T) | ATM | Ataxia, neurodegeneration |

| A-T like disorder (A-TLD) | MRE11 | Ataxia, neurodegeneration |

| Seckel syndrome | ATR | Microcephaly |

| Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome (NBS) | NBS1 | Microcephaly |

| NBS-like syndrome | RAD50 | Microcephaly |

| LIG4 syndrome | DNA-LIGASEIV | Microcephaly |

| Fanconi Anemia | FANC genes | Microcephaly |

| Cernunnos sydrome | Cernunnos/XLF | Microcephaly |

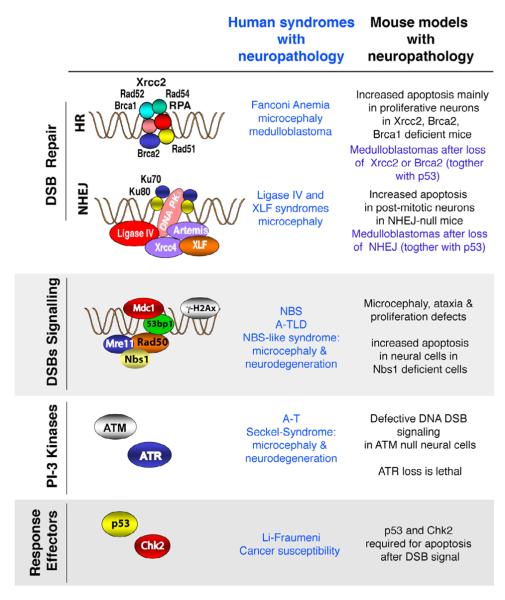

Figure 2. Defects in DNA damage signaling can lead to neurological disease.

The DNA DSB response involves a variety of different factors that activate DNA repair or DNA signaling. DNA DSBs are repaired by either non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR); each pathway involves distinct molecular machinery. DNA damage is detected by sensors that involve the MRN complex and signaling effectors such as ATM or ATR that activate down-stream signaling that functions to activate cell cycle checkpoints or elimination of the cell via activation of apoptosis. When these processes are disrupted human syndromes that feature neuropathology can occur. Genetic manipulation of the mouse is being used to mimic these DNA damage defective syndromes. Representative human syndromes are listed that result from defective DNA damage responses together with comparative phenotypes that occur in mouse models.

While Ku70/80 or DNA-PKcs-deficient mice are viable, there is increased apoptosis in the Ku-null nervous system, although not in that of DNA-PKcs-null mice [54]. The increased apoptosis present in Ku70 and Ku80-deficient embryos was localized to the developing spinal cord, cerebral cortex, midbrain and hindbrain [54]. Apoptosis has also been found in the embryonic retina in Ku-null animals [64]. It has been suggested that neuronal cells might be especially prone to apoptosis in response to DSBs perhaps as a means to eliminate damaged neurons during development [28]. The ability of the Ku null mice to form a relatively intact nervous system suggests that the level of DNA DSBs is below that of the Lig4-null mice, and that sufficient cell replacement occurred to maintain neural development. Notably, Ku deficiency was shown to rescue embryonic lethality in some Lig4-null animals [65]. While the reason for the viability of the small percentage of Lig4/Ku double null mutants is not certain, it has been suggested that in the absence of Ku the DNA-PKcs-Artemis nuclease complex did not load onto the DNA, and thus minimized DNA erosion in absence of Lig4. Presumably, this reduced DNA degradation did not effectively activate apoptosis and was sufficient to promote viability in some Lig4-null animals. Thus, normal development of the nervous system has a particular reliance on NHEJ.

The role of HR during mouse brain development

Inactivation of many central HR proteins leads to embryonic lethality around gastrulation [45]. This early lethality points to the well-described and critical importance of these factors during cellular proliferation to maintain genomic integrity. However, while in most cases this precludes in-depth analysis of their function during neural development, some limited examples do help to provide key insights about how HR interfaces with neural development. Additionally, circumvention of this limitation has been afforded by the use of conditional gene ablation in which the spatiotemporal gene inactivation can be controlled [66].

Important HR factors, including Xrcc2, Brca1 and Brca2, that have been inactivated in the mouse have provided important information about their role during neural development. Germline inactivation of Xrcc2 led to embryonic lethality by early to mid-gestation associated with profound apoptosis [46,67]. While Xrcc2 loss usually led to lethality around embryonic day 10, when little neural development had commenced, some embryos survived longer to stages when it was possible to perform detailed analysis of the developing nervous system. In these embryos, Xrcc2 loss was characterized by extensive apoptosis throughout the VZ of developing nervous system, clearly showing Xrcc2 loss only affected proliferating cells [46]. This suggested that HR is essential for the repair of DSBs in proliferating cells, and that NHEJ is not able to substitute for loss of HR cells. Similar to NHEJ mutants, loss of p53 was able to rescue the lethality associated with Xrcc2 inactivation, and the resulting mice were highly cancer prone, and developed a wide spectrum of malignancy including brain tumors.

Inactivation of Brca1 also resulted in very early lethality, although some Brca1 mutant mice were obtained by inactivating exon 11 which allowed development until mid-gestation [68,69]. The majority of the mutant embryos exhibited neural tube developmental abnormalities such as spina bifida and anencephaly, and the neuroepithelium of Brca1 deficient embryos exhibited increased apoptosis [68]. Similar to these findings, Xu et al., demonstrated that lack of Brca1 led to widespread apoptosis within the nervous system associated with developmental defects such as exencephaly [69]. Finally, similar to example of Lig4 or Xrcc4 deficiency, p53 heterozygosity rescued the phenotype suggesting that many of the defects in Brca1 deficient embryos were p53 dependent [69].

Germline inactivation of Brca2 also leads to very early embryonic lethality in the mouse precluding assessment of its contribution to neural function [70–72]. However, a recent study using conditional inactivation of Brca2 throughout the nervous system bypassed embryonic lethality and showed that loss of Brca2 led to microcephaly and impaired development of the cerebellum [73]. These neurodevelopmental defects were mainly associated with increased DNA damage-induced apoptosis in proliferative cells but also in early post-mitotic neurons. Inactivation of p53 contributed to a significant but incomplete rescue of this phenotype by preventing cell loss associated with DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Similar to the defects in NHEJ, simultaneous inactivation of p53 with Brca2 loss led to rapid development of medulloblastoma [73]. The importance of BRCA2 in the nervous system is also underscored Fanconi anemia (FA) which can result from disruption of anyone of a number of proteins required for DNA crosslink repair, including BRCA2 [74]. FA individuals that results from bi-allelic BRCA2 inactivation manifest neurodevelopmental abnormalities, and are prone to brain tumors [75]. Thus, HR is an important DNA repair pathway that is required for neural homeostasis, and its perturbation can result in disease (Figure 2).

DSBs signaling and human neurological disorder

Coincident with DNA DSB repair is the activation of specific signaling events that serve to initiate cell cycle arrest to facilitate DNA repair. DNA DSBs induce rapid phosphorylation of the histone H2A variant H2AX, which facilitates the recruitment of numerous proteins including NBS1, MDC1 and 53BP1 to the vicinity of the break [76–78]. These events amplify DNA DSB signaling by the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase to modulate the activity of multiple target proteins involved in cell-cycle checkpoints and DNA repair pathways. ATM is a key protein kinase that functions at the apex of a signaling pathway that coordinates cell cycle arrest after DNA damage [79]. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of cell-cycle checkpoint effectors such as p53, Chk2, SMC1, BRCA1, and NBS1 occurs to activate G1, intra-S and G2/M checkpoints. Detailed descriptions of ATM-signaling after DNA damage have recently been published [78,80–82]. Simultaneously with DNA damage induced foci formation of factors that activate cell-cycle checkpoints, DNA repair machinery also co-localizes to the DSB [83,84]. See also other contributions in this volume for detailed discussion of the link between ATM-signaling and neurological disease.

An ATM-related protein kinase, ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) also participates in DNA damage signaling. ATM and ATR are both critical for nervous system function and can phosphorylate many common substrates including p53, NBS1, BRCA1 and Chk1 in response to DNA damage [85,86]. Furthermore, in response to DNA DSBs there is an ATM-dependent requirement for ATR signaling, whereby in the absence of ATM activation of a Chk1-dependent cell cycle checkpoint after ionizing radiation is delayed [87–90]. Additionally, ATM and ATR act cooperatively and in collaboration with Mre11 during the initiation and regulation of replication, and function to halt these processes when DNA damage is detected [87,91,92]. A shared role for ATM and ATR in telomere maintenance and modulation of FANCD2 has also been demonstrated [93,94]. Although the targets of ATM (and ATR) have been well characterized, they may be more diverse than previously thought as recent studies demonstrate that around 700 proteins can be phosphorylated by these kinases in response to ionizing radiation [95]. However, these kinases have non-overlapping functions, as defects in each lead to distinct neurological diseases in humans (Figure 2); inactivation of ATM leads to the neurodegenerative syndrome ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T), while hypomorphic mutations of ATR can lead to ATR-Seckel syndrome (Table 1) [3,63,96,97]. In the mouse, inactivation of ATR is lethal very early during development, while mice lacking ATM are viable, and although tumor-prone can often have a normal lifespan [98,99].

Inactivation of murine Atm has provided important information about the tissue-specific function of this kinase. Atm-null mice are hypersensitive to radiation because of gut and hematopoietic sensitivity and are sterile and cancer prone, although they fail to recapitulate the overt neurodegeneration found in the human syndrome [98,100–102]. However, Atm-null neurons showed a striking resistance to apoptosis after DNA damage resulting from a lack of p53 activation [101]. The protective effect of Atm deficiency after DNA damage was associated with post-mitotic neurons but not proliferating neural cells [46,103]. Accordingly, ATM deficiency did not efficiently rescue the neurogenesis defects associated with the loss of HR proteins such as Xrcc2 or Brca2, but did lead to substantial neural rescue after loss of the NHEJ factor, Lig4 [46,53,103,104]. These data suggest that ATM functions as a genomic surveillance factor in the developing nervous system that monitors cells as they exit the cell cycle to activate apoptosis and eliminate cells that have incurred genomic damage.

Linked to ATM activation, the MRN complex is also critical for the DNA DSB response [105–107]. MRN is composed of Mre11, Rad50 and Nbs1 and is involved in DNA repair, DNA damage signaling, cell cycle checkpoints and telomere maintenance [108]. Hypomorphic mutations of MRN components lead to ataxia-telangiectasia like disorder (A-TLD) for Mre11 and Nijmegen Breakage syndrome (NBS) for NBS1 (Table 1) [108–111]. These syndromes exhibit neuropathology including progressive neurodegeneration in A-TLD and microcephaly in NBS. Inactivation of any of the MRN proteins in the mouse leads to early embryonic lethality [112–114]. Mice expressing truncated or mutated proteins as disease models have also been generated (Nbs1 [115,116], Mre11 [117] and Rad50 [118]), although none of them fully recapitulated the human syndrome. In fact, while mouse models of DNA repair syndromes appear to mimic many of the human disease phenotypes, they often don't show defects in the nervous system to the same extent as humans. However, new approaches such as conditional gene inactivation are providing important new information about the tissue-specific requirements of DNA repair factors. Recently, conditional inactivation of Nbs1 in the mouse central nervous system resulted in neurological aspects reflective of NBS in which profound microcephaly associated with ataxia was observed [119]. Loss of Nbs1 was particularly severe in the cerebellum, which presented with an absence of foliation and an ectopic localization of Purkinje cells. This phenotype was also associated with proliferation defects in progenitor cells and increased apoptosis in post-mitotic neurons, a phenomenon that required p53 signaling [119]. Together these data highlight the key role of Nbs1, and by association the MRN complex and its signaling partners, in the maintenance and protection of the central nervous system against DSBs during development.

Summary & Perspectives

A large number of different cell types integrate function in the nervous system, and this diversity presents a challenge for understanding the dynamics of the DNA damage response required for homeostasis in the brain. DNA repair defects can lead to neuropathology affecting diverse neural tissue resulting in debilitating neurodegeneration, microcephaly or brain tumors. Therapeutic approaches for treating DNA repair diseases will require a multifaceted understanding of the requirement for DNA damage signaling during all stages of neural development, including that of mature neural tissue. While all of the human syndromes discussed above result from defects during developmental, it is less clear if any aspect of the disease phenotype reflects a requirement for the respective gene products in the adult, and if effects at later stages are secondary to problems incurred during development.

A powerful approach to experimentally address these issues is the genetic manipulation of DNA repair factors in the mouse. Already, substantial knowledge has been gained following germline disruption of many DNA repair factors, although in many cases this leads to lethality, precluding a detailed neural analysis [45]. Presently, analyses involving tissue-specific inactivation of DNA repair have been particularly informative about specific biological requirements for DNA repair factors in this tissue. It is clear that as these studies progress, many of the outstanding questions regarding tissue requirements for DNA repair pathways will be answered.

While mouse models provide a unique biological perspective for tissue-specific effects of DNA damage, some limitations exist in modelling human disease in the mouse. This is particularly problematic in the nervous system, in which the mouse appears to be markedly resistant to DNA damage compared with humans. For example, Atm-null mice don't manifest the overt ataxia typical of human ATM loss and similarly hypomorphic mutation of Mre11 that results in neurodegeneration and A-TLD in humans doesn't appear to lead to neurodegeneration in mice. However, as mouse models become more refined, current limitations will be overcome for example by using combinatorial gene inactivation approaches to mimic the neuropathology seen in human diseases, and will provide a clear view of the biology of DNA repair and how this process functions to prevent disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Williams RW, Herrup K. The control of neuron number. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:423–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Katyal S, McKinnon PJ. DNA Repair Deficiency and Neurodegeneration. Cell Cycle. 2007;6 doi: 10.4161/cc.6.19.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McKinnon PJ, Caldecott KW. DNA Strand Break Repair and Human Genetic Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:37–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rass U, Ahel I, West SC. Defective DNA repair and neurodegenerative disease. Cell. 2007;130:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cleaver JE. Cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum and related disorders of DNA repair. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:564–573. doi: 10.1038/nrc1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rolig RL, McKinnon PJ. Linking DNA damage and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:417–424. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nouspikel T, Hanawalt PC. When parsimony backfires: neglecting DNA repair may doom neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Bioessays. 2003;25:168–173. doi: 10.1002/bies.10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shackelford DA. DNA end joining activity is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jacobsen M. Developmental Neurobiology. Plenum Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chan WY, Lorke DE, Tiu SC, Yew DT. Proliferation and apoptosis in the developing human neocortex. Anat Rec. 2002;267:261–276. doi: 10.1002/ar.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dehay C, Kennedy H. Cell-cycle control and cortical development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:438–450. doi: 10.1038/nrn2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Goldowitz D, Hamre K. The cells and molecules that make a cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huang ZJ, Di Cristo G, Ango F. Development of GABA innervation in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:673–686. doi: 10.1038/nrn2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang VY, Zoghbi HY. Genetic regulation of cerebellar development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:484–491. doi: 10.1038/35081558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Masland RH. Neuronal cell types. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Masland RH. Neuronal diversity in the retina. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Battiste J, Helms AW, Kim EJ, Savage TK, Lagace DC, Mandyam CD, Eisch AJ, Miyoshi G, Johnson JE. Ascl1 defines sequentially generated lineage-restricted neuronal and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the spinal cord. Development. 2007;134:285–293. doi: 10.1242/dev.02727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Helleday T, Lo J, van Gent DC, Engelward BP. DNA double-strand break repair: from mechanistic understanding to cancer treatment. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].West SC. Molecular views of recombination proteins and their control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:435–445. doi: 10.1038/nrm1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:712–720. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aimone JB, Wiles J, Gage FH. Potential role for adult neurogenesis in the encoding of time in new memories. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:723–727. doi: 10.1038/nn1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bhardwaj RD, Curtis MA, Spalding KL, Buchholz BA, Fink D, Bjork-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, Gage FH, Druid H, Eriksson PS, Frisen J. Neocortical neurogenesis in humans is restricted to development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12564–12568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605177103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lie DC, Colamarino SA, Song HJ, Desire L, Mira H, Consiglio A, Lein ES, Jessberger S, Lansford H, Dearie AR, Gage FH. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437:1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006;442:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fraser MM, Zhu X, Kwon CH, Uhlmann EJ, Gutmann DH, Baker SJ. Pten loss causes hypertrophy and increased proliferation of astrocytes in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7773–7779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koguchi K, Nakatsuji Y, Nakayama K, Sakoda S. Modulation of astrocyte proliferation by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) Glia. 2002;37:93–104. doi: 10.1002/glia.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Santambrogio L, Belyanskaya SL, Fischer FR, Cipriani B, Brosnan CF, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Stern LJ, Strominger JL, Riese R. Developmental plasticity of CNS microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6295–6300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lee Y, McKinnon PJ. Responding to DNA double strand breaks in the nervous system. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1365–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Thacker J, Zdzienicka MZ. The mammalian XRCC genes: their roles in DNA repair and genetic stability. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:655–672. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Limbo O, Chahwan C, Yamada Y, de Bruin RA, Wittenberg C, Russell P. Ctp1 is a cell-cycle-regulated protein that functions with Mre11 complex to control double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2007;28:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Takeda S, Nakamura K, Taniguchi Y, Paull TT. Ctp1/CtIP and the MRN complex collaborate in the initial steps of homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2007;28:351–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Heyer WD, Li X, Rolfsmeier M, Zhang XP. Rad54: the Swiss Army knife of homologous recombination? Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4115–4125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Thacker J, Zdzienicka MZ. The XRCC genes: expanding roles in DNA double-strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wyman C, Ristic D, Kanaar R. Homologous recombination-mediated double-strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:827–833. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bassing CH, Alt FW. The cellular response to general and programmed DNA double strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lees-Miller SP, Meek K. Repair of DNA double strand breaks by non-homologous end joining. Biochimie. 2003;85:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Burma S, Chen DJ. Role of DNA-PK in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, Barraud A, Fondaneche MC, Sanal O, Plebani A, Stephan JL, Hufnagel M, le Deist F, Fischer A, Durandy A, de Villartay JP, Revy P. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jeggo P, O'Neill P. The Greek Goddess, Artemis, reveals the secrets of her cleavage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:771–777. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Moshous D, Callebaut I, de Chasseval R, Corneo B, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, Tezcan I, Sanal O, Bertrand Y, Philippe N, Fischer A, de Villartay JP. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell. 2001;105:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Esashi F, Christ N, Gannon J, Liu Y, Hunt T, Jasin M, West SC. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA2 as a regulatory mechanism for recombinational repair. Nature. 2005;434:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nature03404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sharma S. Age-related nonhomologous end joining activity in rat neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2007;73:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Friedberg EC, Meira LB. Database of mouse strains carrying targeted mutations in genes affecting biological responses to DNA damage Version 7. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:189–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Orii KE, Lee Y, Kondo N, McKinnon PJ. Selective utilization of nonhomologous end-joining and homologous recombination DNA repair pathways during nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10017–10022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Couedel C, Mills KD, Barchi M, Shen L, Olshen A, Johnson RD, Nussenzweig A, Essers J, Kanaar R, Li GC, Alt FW, Jasin M. Collaboration of homologous recombination and nonhomologous end-joining factors for the survival and integrity of mice and cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1293–1304. doi: 10.1101/gad.1209204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mills KD, Ferguson DO, Essers J, Eckersdorff M, Kanaar R, Alt FW. Rad54 and DNA Ligase IV cooperate to maintain mammalian chromatid stability. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1283–1292. doi: 10.1101/gad.1204304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Barnes DE, Stamp G, Rosewell I, Denzel A, Lindahl T. Targeted disruption of the gene encoding DNA ligase IV leads to lethality in embryonic mice. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1395–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Frank KM, Sharpless NE, Gao Y, Sekiguchi JM, Ferguson DO, Zhu C, Manis JP, Horner J, DePinho RA, Alt FW. DNA Ligase IV Deficiency in Mice Leads to Defective Neurogenesis and Embryonic Lethality via the p53 Pathway. Mol Cell. 2000;5:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gao Y, Sun Y, Frank KM, Dikkes P, Fujiwara Y, Seidl KJ, Sekiguchi JM, Rathbun GA, Swat W, Wang J, Bronson RT, Malynn BA, Bryans M, Zhu C, Chaudhuri J, Davidson L, Ferrini R, Stamato T, Orkin SH, Greenberg ME, Alt FW. A critical role for DNA end-joining proteins in both lymphogenesis and neurogenesis. Cell. 1998;95:891–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lee Y, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, McKinnon PJ. Defective neurogenesis resulting from DNA ligase IV deficiency requires Atm. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2576–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.837100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sekiguchi J, Ferguson DO, Chen HT, Yang EM, Earle J, Frank K, Whitlow S, Gu Y, Xu Y, Nussenzweig A, Alt FW. Genetic interactions between ATM and the nonhomologous end-joining factors in genomic stability and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gu Y, Sekiguchi J, Gao Y, Dikkes P, Frank K, Ferguson D, Hasty P, Chun J, Alt FW. Defective embryonic neurogenesis in Ku-deficient but not DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2668–2673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li L, Salido E, Zhou Y, Bhattacharyya S, Yannone SM, Dunn E, Meneses J, Feeney AJ, Cowan MJ. Targeted disruption of the Artemis murine counterpart results in SCID and defective V(D)J recombination that is partially corrected with bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2005;174:2420–2428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rooney S, Alt FW, Sekiguchi J, Manis JP. Artemis-independent functions of DNA-dependent protein kinase in Ig heavy chain class switch recombination and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2471–2475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zha S, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Brush JW, Li G. Defective DNA repair and increased genomic instability in Cernunnos-XLF-deficient murine ES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4518–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611734104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Karanjawala ZE, Murphy N, Hinton DR, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Oxygen metabolism causes chromosome breaks and is associated with the neuronal apoptosis observed in DNA double-strand break repair mutants. Curr Biol. 2002;12:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gao Y, Ferguson DO, Xie W, Manis JP, Sekiguchi J, Frank KM, Chaudhuri J, Horner J, DePinho RA, Alt FW. Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genomic stability and development. Nature. 2000;404:897–900. doi: 10.1038/35009138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lee Y, McKinnon PJ. DNA ligase IV suppresses medulloblastoma formation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6395–6399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yan CT, Kaushal D, Murphy M, Zhang Y, Datta A, Chen C, Monroe B, Mostoslavsky G, Coakley K, Gao Y, Mills KD, Fazeli AP, Tepsuporn S, Hall G, Mulligan R, Fox E, Bronson R, De Girolami U, Lee C, Alt FW. XRCC4 suppresses medulloblastomas with recurrent translocations in p53-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103(2006):7378–7383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].O'Driscoll M, Cerosaletti KM, Girard PM, Dai Y, Stumm M, Kysela B, Hirsch B, Gennery A, Palmer SE, Seidel J, Gatti RA, Varon R, Oettinger MA, Neitzel H, Jeggo PA, Concannon P. DNA ligase IV mutations identified in patients exhibiting developmental delay and immunodeficiency. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].O'Driscoll M, Gennery AR, Seidel J, Concannon P, Jeggo PA. An overview of three new disorders associated with genetic instability: LIG4 syndrome, RS-SCID and ATR-Seckel syndrome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1227–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Karanjawala ZE, Hinton DR, Oh E, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Developmental retinal apoptosis in Ku86−/− mice. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:1429–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Karanjawala ZE, Adachi N, Irvine RA, Oh EK, Shibata D, Schwarz K, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. The embryonic lethality in DNA ligase IV-deficient mice is rescued by deletion of Ku: implications for unifying the heterogeneous phenotypes of NHEJ mutants. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Jonkers J, Berns A. Conditional mouse models of sporadic cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:251–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Deans B, Griffin CS, Maconochie M, Thacker J. Xrcc2 is required for genetic stability, embryonic neurogenesis and viability in mice. Embo J. 2000;19:6675–6685. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gowen LC, Johnson BL, Latour AM, Sulik KK, Koller BH. Brca1 deficiency results in early embryonic lethality characterized by neuroepithelial abnormalities. Nat Genet. 1996;12:191–194. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Xu X, Qiao W, Linke SP, Cao L, Li WM, Furth PA, Harris CC, Deng CX. Genetic interactions between tumor suppressors Brca1 and p53 in apoptosis, cell cycle and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:266–271. doi: 10.1038/90108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Ludwig T, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A. Targeted mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene homologs in mice: lethal phenotypes of Brca1, Brca2, Brca1/Brca2, Brca1/p53, and Brca2/p53 nullizygous embryos. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1226–1241. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sharan SK, Bradley A. Murine Brca2: sequence, map position, and expression pattern. Genomics. 1997;40:234–241. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Hakem R, Elia A, Yoshida R, Mo R, Nishina H, Chuang T, Wakeham A, Itie A, Koo W, Billia P, Ho A, Fukumoto M, Hui CC, Mak TW. Brca2 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1242–1252. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Frappart PO, Lee Y, Lamont J, McKinnon PJ. BRCA2 is required for neurogenesis and suppression of medulloblastoma. Embo J. 2007;26:2732–2742. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].D'Andrea AD, Grompe M. The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Offit K, Levran O, Mullaney B, Mah K, Nafa K, Batish SD, Diotti R, Schneider H, Deffenbaugh A, Scholl T, Proud VK, Robson M, Norton L, Ellis N, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD. Shared genetic susceptibility to breast cancer, brain tumors, and Fanconi anemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1548–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Kruhlak MJ, Pilch DR, Staudt DW, Lee A, Bonner RF, Bonner WM, Nussenzweig A. Histone H2AX phosphorylation is dispensable for the initial recognition of DNA breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:675–679. doi: 10.1038/ncb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sedelnikova OA, Pilch DR, Redon C, Bonner WM. Histone H2AX in DNA damage and repair. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:233–235. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ward I, Chen J. Early events in the DNA damage response. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;63:1–35. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)63001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Lavin MF, Kozlov S. ATM Activation and DNA Damage Response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6 doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Shiloh Y. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: taking shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Berkovich E, Monnat RJ, Jr., Kastan MB. Roles of ATM and NBS1 in chromatin structure modulation and DNA double-strand break repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:683–690. doi: 10.1038/ncb1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Yang YG, Saidi A, Frappart PO, Min W, Barrucand C, Dumon-Jones V, Michelon J, Herceg Z, Wang ZQ. Conditional deletion of Nbs1 in murine cells reveals its role in branching repair pathways of DNA double-strand breaks. Embo J. 2006;25:5527–5538. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–2196. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Shiloh Y. ATM and ATR: networking cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Adams KE, Medhurst AL, Dart DA, Lakin ND. Recruitment of ATR to sites of ionising radiation-induced DNA damage requires ATM and components of the MRN protein complex. Oncogene. 2006;25:3894–3904. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cuadrado M, Martinez-Pastor B, Murga M, Toledo LI, Gutierrez-Martinez P, Lopez E, Fernandez-Capetillo O. ATM regulates ATR chromatin loading in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Exp Med. 2006;203:297–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP. ATM-and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Myers JS, Cortez D. Rapid activation of ATR by ionizing radiation requires ATM and Mre11. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9346–9350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513265200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Shechter D, Costanzo V, Gautier J. ATR and ATM regulate the timing of DNA replication origin firing. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:648–655. doi: 10.1038/ncb1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Trenz K, Smith E, Smith S, Costanzo V. ATM and ATR promote Mre11 dependent restart of collapsed replication forks and prevent accumulation of DNA breaks. Embo J. 2006;25:1764–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bi X, Srikanta D, Fanti L, Pimpinelli S, Badugu R, Kellum R, Rong YS. Drosophila ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases control partially redundant pathways for telomere maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15167–15172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504981102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ho GP, Margossian S, Taniguchi T, A.D. D'Andrea Phosphorylation of FANCD2 on two novel sites is required for mitomycin C resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7005–7015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02018-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].McKinnon PJ. ATM and ataxia telangiectasia. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:772–776. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].O'Driscoll M, Jeggo PA. The role of double-strand break repair - insights from human genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:45–54. doi: 10.1038/nrg1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Barlow C, Hirotsune S, Paylor R, Liyanage M, Eckhaus M, Collins F, Shiloh Y, Crawley JN, Ried T, Tagle D, Wynshaw-Boris A. Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1996;86:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Brown EJ, Baltimore D. ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 2000;14:397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Elson A, Wang Y, Daugherty CJ, Morton CC, Zhou F, Campos-Torres J, Leder P. Pleiotropic defects in ataxia-telangiectasia protein-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (USA) 1996;93:13084–13089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Herzog KH, Chong MJ, Kapsetaki M, Morgan JI, McKinnon PJ. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998;280:1089–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Xu Y, Ashley T, Brainerd EE, Bronson RT, Meyn MS, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of ATM leads to growth retardation, chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, immune defects, and thymic lymphoma. Genes and Development. 1996;10:2411–2422. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Lee Y, Chong MJ, McKinnon PJ. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated-dependent apoptosis after genotoxic stress in the developing nervous system is determined by cellular differentiation status. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6687–6693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06687.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Frappart PO, McKinnon PJ. BRCA2 Function and the Central Nervous System. Cell Cycle. 2007;6 doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Carson CT, Schwartz RA, Stracker TH, Lilley CE, Lee DV, Weitzman MD. The Mre11 complex is required for ATM activation and the G(2)/M checkpoint. Embo J. 2003;22:6610–6620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Difilippantonio S, Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Reina San Martin B, Van Laethem F, Yang YP, Petukhova GV, Eckhaus M, Feigenbaum L, Manova K, Kruhlak M, Camerini-Otero RD, Sharan S, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. Role of Nbs1 in the activation of the Atm kinase revealed in humanized mouse models. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:675–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L, Andegeko Y, Mittelman L, Shiloh Y. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. Embo J. 2003;22:5612–5621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Stracker TH, Theunissen JW, Morales M, Petrini JH. The Mre11 complex and the metabolism of chromosome breaks: the importance of communicating and holding things together. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Carney JP, Maser RS, Olivares H, Davis EM, Le Beau M, Yates JR, 3rd, Hays L, Morgan WF, Petrini JH. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell. 1998;93:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Stewart GS, Maser RS, Stankovic T, Bressan DA, Kaplan MI, Jaspers NG, Raams A, Byrd PJ, Petrini JH, Taylor AM. The DNA double-strand break repair gene hMRE11 is mutated in individuals with an ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder. Cell. 1999;99:577–587. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Taylor AM, Groom A, Byrd PJ. Ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder (ATLD)-its clinical presentation and molecular basis. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Luo G, Yao MS, Bender CF, Mills M, Bladl AR, Bradley A, Petrini JH. Disruption of mRad50 causes embryonic stem cell lethality, abnormal embryonic development, and sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7376–7381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Xiao Y, Weaver DT. Conditional gene targeted deletion by Cre recombinase demonstrates the requirement for the double-strand break repair Mre11 protein in murine embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2985–2991. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.15.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Zhu J, Petersen S, Tessarollo L, Nussenzweig A. Targeted disruption of the Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene NBS1 leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Curr Biol. 2001;11:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Kang J, Bronson RT, Xu Y. Targeted disruption of NBS1 reveals its roles in mouse development and DNA repair. Embo J. 2002;21:1447–1455. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Williams BR, Mirzoeva OK, Morgan WF, Lin J, Dunnick W, Petrini JH. A murine model of nijmegen breakage syndrome. Curr Biol. 2002;12:648–653. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Theunissen JW, Kaplan MI, Hunt PA, Williams BR, Ferguson DO, Alt FW, Petrini JH. Checkpoint failure and chromosomal instability without lymphomagenesis in Mre11(ATLD1/ATLD1) mice. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1511–1523. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Bender CF, Sikes ML, Sullivan R, Huye LE, Le Beau MM, Roth DB, Mirzoeva OK, Oltz EM, Petrini JH. Cancer predisposition and hematopoietic failure in Rad50(S/S) mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2237–2251. doi: 10.1101/gad.1007902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Frappart PO, Tong WM, Demuth I, Radovanovic I, Herceg Z, Aguzzi A, Digweed M, Wang ZQ. An essential function for NBS1 in the prevention of ataxia and cerebellar defects. Nat Med. 2005;11:538–544. doi: 10.1038/nm1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]