Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MS) and new onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT) are common in kidney transplant patients. We studied the relationship between the two conditions and their impact on metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles.

Methods

All non-diabetic patients transplanted between 1999 and 2005 who were followed up to 2006 were included. MS and NODAT were determined. Kaplan–Meier survival and various regression analyses were performed to determine the clinical correlates for both conditions and their association with various cardiovascular risk factors.

Results

Among 591 patients, 314 (53.1%) had MS and 90 (15.2%) developed NODAT. The two conditions were highly associated with each other as 84 patients with NODAT also had MS (14.2%). Elevated body mass index and fasting glucose levels at transplant were risk factors for both conditions, whereas weight gain after transplant was associated only with MS. African American, old age, and hypertension-related ESRD were risk factors for NODAT. Finally, the presence of MS was associated with reduced kidney function and elevated uric acid levels, whereas the presence of NODAT with elevated pulse pressure.

Conclusions

MS and NODAT are highly prevalent and significantly associated with impaired metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles. Early identification of such conditions may facilitate targeted therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: kidney transplant, metabolic syndrome, new onset diabetes

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is a constellation of metabolic and non-metabolic disorders that is very common in kidney transplant recipients and associated with impaired long-term renal allograft function and poor patient survival (1, 2). New onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT) is also a common metabolic complication following kidney transplantation (3, 4). The early diagnosed NODAT is associated with increased cardiovascular events and mortality (5–7). In addition, various components of MS are shown to be risk factors for the development of abnormal glucose metabolism and NODAT (3, 8).

Current guidelines recommend using either fasting glucose criteria or oral glucose tolerance to diagnose abnormal glucose metabolism (9–11). Timely recognition of MS and NODAT is of great importance and may allow for appropriate intervention to prevent or reduce the long-lasting deleterious effects of both conditions on patient and allograft survival.

We performed a retrospective and cross-sectional observational study investigating the relationship between MS and NODAT, their clinical predictors, and their impact on metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles in a previously non-diabetic kidney transplant patient population.

Patients and methods

This is a single center retrospective and cross-sectional observational study approved by the institutional review board.

All previously non-diabetic kidney transplant patients between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2005, who were alive with a functioning transplant on December 31, 2006, were included. Demographic and baseline characteristics were collected at the time of kidney transplantation. Fasting blood glucose levels were collected prior to transplantation and at the most recent follow-up. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height squared (meter2) and was measured at the time of transplantation and at the most recent follow-up. Blood pressure measurement and a fasting lipid panel were obtained during their most recent follow-up clinic visit as well.

Metabolic syndrome (MS) was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Expert Panel (NCEP) criteria using BMI as surrogate for waist circumference (12–14). A patient was classified as having MS if three or more of the following criteria were present: BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater, plasma fasting glucose levels of 100 mg/dL or greater, presence of hypertension (130/85 mmHg or greater, or on any anti-hypertensive medication), fasting triglyceride of 150 mg/dL or greater, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) of less than 40 mg/dL for men or less than 50 mg/dL for women. New onset diabetes mellitus after transplant (NODAT) was defined by a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL on two separate occasions, or being initiated on insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents between transplant and the latest follow-up.

Immunosuppression was provided according to the center standard protocols. Induction was given selectively to patients with high immunologic risk using rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) or anti-IL2 receptor antibodies (basiliximab). All patients were started on a triple drug regimen which included a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), either cyclosporine (CsA) or tacrolimus (Tac), an anti-proliferative agent, either mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or sirolimus (Rap), and steroids. The dose of calcineurin inhibitor was determined by targeted trough concentrations. The 12-h trough levels were maintained between 100 to 150 ng/mL for CsA and 5 to 8 ng/mL for Tac for stable patients beyond the first 10–12 wk after transplantation. During the course of years, some patients had a change in the use of a particular CNI as determined clinically by transplant nephrologists. Thus, the use of different CNIs for a given patient and their blood concentration at the last follow-up was determined as well. The dose of steroids followed a center-specific prednisone tapering schedule down to 10 mg daily 8 wk after transplantation and maintained at 5–10 mg daily during the subsequent follow-up. All episodes of acute rejection were diagnosed with an allograft biopsy. Treatment was tailored according to the severity of rejection.

Continuous and categorical variables were compared using the Student's t-test or ANOVA as appropriate and chi-square test between the groups. The Kaplan–Meier method was utilized to estimate NODAT-free survival stratified by the presence of MS. Multivariate logistic and Cox regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for MS and NODAT, respectively. Multivariate linear models were used to determine the factors associated with renal function, blood uric acid levels, and pulse pressure at the most recent follow-up. Statistical software SAS 9.1 was used to perform all analyses. Statistical significance was set at a p value of ≤ 0.05.

Results

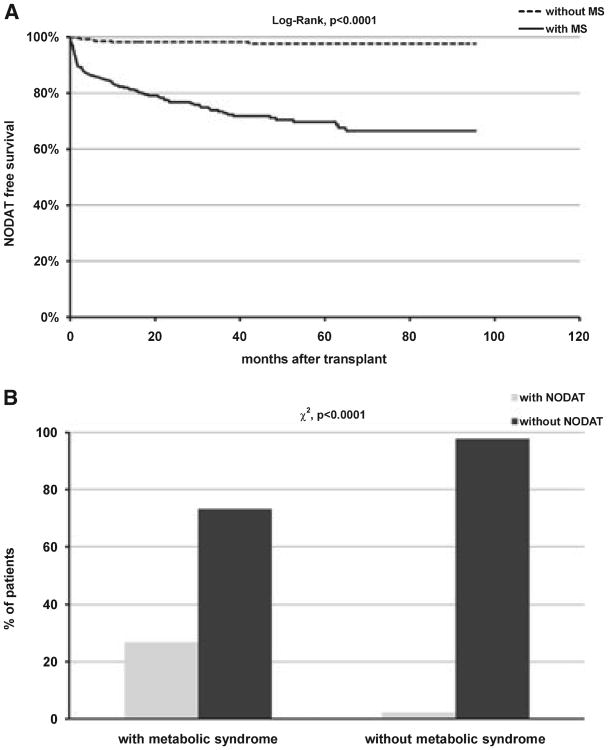

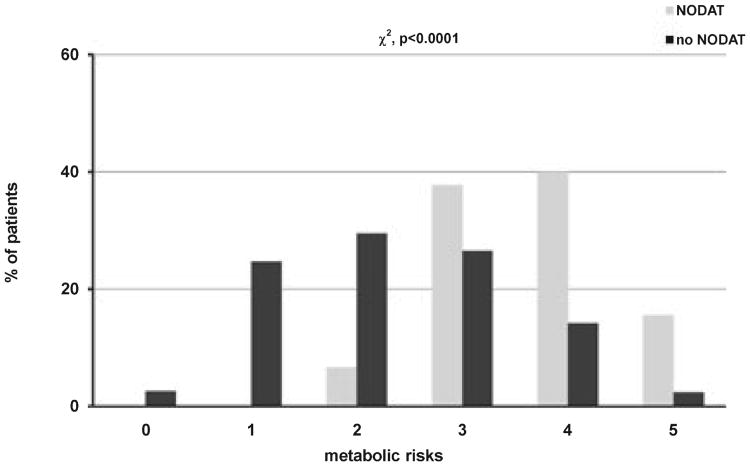

A total of 591 kidney transplant patients from the center database met the inclusion criteria. The median follow-up for this cohort was 47.7 months after transplantation with a range between 12.5 to 96.0 months. Overall, 314 patients (53.1%) met the definition of metabolic syndrome, and 90 patients (15.2%) were diagnosed with new onset diabetes. A total of 84 patients (14.2%) had both conditions. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and baseline characteristics of study patients grouped according to the presence of either condition alone or in combination. Overall, there were significant differences in age, fasting glucose levels, and BMI at transplant among patients within different groups. African American patients were over-represented in NODAT with and without MS. The use of different CNIs at transplant and at last follow-up was not statistically different. Similarly, the trough concentration of CNIs was not statistically different as well. There were significantly more cases of NODAT during the study period in patients who met the criteria for the diagnosis of MS at the end of follow-up (log-rank p < 0.0001), and the two conditions were highly associated with each other (χ2, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A,B). Patients who developed NODAT also had a significantly higher number of metabolic derangements that are part of MS after adjusting for the use of statins and the number of anti-hypertensive medications (OR 3.01, 95% CI 2.30, 3.94, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2).

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of study patient population.

| None N = 271 | MS N = 230 | NODAT N = 6 | MS/NODATa N = 84 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 43.3 (13.4) | 45.6 (13.0) | 55.8 (14.2) | 51.5 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 146 (53.9) | 135 (58.7) | 3 (50.0) | 49 (58.3) | 0.70 |

| African American (%) | 33 (12.2) | 30 (13.4) | 1 (16.7) | 21 (25.0) | 0.03 |

| Living donor transplant (%) | 172 (63.5) | 130 (56.5) | 3 (50.0) | 49 (58.3) | 0.39 |

| First transplant (%) | 231 (85.2) | 198 (86.1) | 6 (100) | 74 (88.1) | 0.95 |

| HCV-positive serology (%) | 6 (2.2) | 9 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.8) | 0.46 |

| FBGb, mg/dL (SD) | 85.1 (9.3) | 87.3 (8.7) | 87.5 (5.6) | 92.4 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 24.8 (4.4) | 28.7 (5.9) | 26.8 (7.0) | 30.7 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Acute rejection, yes (%) | 75 (27.7) | 68 (29.6) | 1 (16.7) | 24 (28.6) | 0.94 |

| CNI at transplant, CsA (%) | 246 (90.8) | 212 (92.2) | 6 (100.0) | 79 (94.1) | 0.93 |

| CNI at last follow-up, CsA (%) | 177 (65.3) | 164 (71.3) | 3 (50.0) | 58 (69.1) | 0.28 |

| CNI trough levels, ng/mL (SD) | |||||

| CsA | 111.3 (24.8) | 115.7 (26.8) | 96.3 (15.0) | 115.0 (22.7) | 0.15 |

| Tac | 6.2 (1.6) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.5 (0.3) | 7.0 (1.7) | 0.25 |

| Prednisone, mg/d (SD) | 7.5 (2.7) | 7.2 (2.6) | 8.3 (2.6) | 7.1 (2.7) | 0.33 |

| Baseline eGFR, mL/min (SD) | 69.3 (18.1) | 68.1 (19.2) | 61.2 (17.4) | 70.1 (19.1) | 0.58 |

MS, metabolic syndrome; NODAT, new onset diabetes after transplant; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; CsA, cyclosporine, eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Patients with both diagnosis.

FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier new onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT)-free survival between patients with and without metabolic syndrome (MS) (A) and association between MS and NODAT (B).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of metabolic syndrome (MS) components between patients with and without new onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT).

Tables 2 and 3 display the clinical correlates for both MS and NODAT by multivariate logistic and Cox regression analyses, respectively. Higher BMI and higher fasting glucose at the time of transplant were individually associated with MS and risk of developing NODAT. The weight gain after transplant was associated with MS but not NODAT. On the other hand, old age, African American race, and hypertension-related end stage renal disease (ESRD) are risk factors for the development of NODAT but not metabolic syndrome. In fact, African American patients and patients with history of hypertensive ESRD have nearly twice high risk for developing NODAT than non-African American patients and patients whose etiology of ESRD was not primarily because of hypertension. Interestingly, HCV-positive serology was correlated with the presence of MS rather than the development of NODAT.

Table 2. Risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome.

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI at transplant (kg/m2) | 1.19 | 1.14, 1.24 | <0.001 |

| Change in BMI (kg/m2) | 1.22 | 1.15, 1.29 | <0.001 |

| FBGa at transplant (mg/dL) | 1.02 | 1.01, 1.04 | 0.011 |

| HCV (positive vs. negative) | 3.34 | 1.05, 10.49 | 0.041 |

BMI, body mass index.

FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Table 3. Time-dependent multivariate analysis of risk factors for new onset diabetes after transplant.

| Variables | Hazard ratio (HR) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI at transplant (kg/m2) | 1.08 | 1.05, 1.12 | <0.001 |

| FBGa at transplant (mg/dL) | 1.05 | 1.03, 1.07 | <0.001 |

| Age (per one yr increase) | 1.04 | 1.02, 1.06 | <0.001 |

| AA (vs. others) | 2.02 | 1.21, 3.38 | 0.007 |

| Hypertensive ESRD (vs. others) | 1.87 | 1.08, 3.25 | 0.026 |

FBG, fasting blood glucose.

As both MS and NODAT were reported to be associated with inferior kidney graft survival, we investigated the effect of the presence of either MS or NODAT on transplant renal function in the form of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (aMDRD) study formula. Using a linear regression model adjusting for multiple covariates, the presence of MS but not NODAT was associated with a modest reduction in renal function (−2.1 mL/min, p = 0.064). When we replaced MS with a covariate indicating the number of various components of MS in a separate model, we showed that the number of MS components was associated negatively with an inferior level of eGFR. Each component of MS was associated with additional reduction in eGFR by 1.9 mL/min (p = 0.008). In particular, the presence of hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL) was associated with 3.5 mL/min reduction in eGFR (p = 0.003). Other factors associated with inferior renal function included the number of previous transplants, old donor age, low baseline renal function, presence of acute rejection, and longer duration of follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of predictors of renal function.

| Variables | Parameter estimates (mL/min) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic syndrome (yes vs. no) | −2.1 | 0.064 |

| Metabolic syndrome components | −1.9 | 0.008 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL) | −3.5 | 0.003 |

| Baseline renal function (mL/min) | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Number of transplants | −2.8 | 0.04 |

| Acute rejection (yes vs. no) | −5.7 | <0.001 |

| Donor age (yr) | −0.30 | <0.001 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | −0.05 | 0.04 |

Finally, at the last follow-up, patients with MS and/or NODAT displayed a worse metabolic and cardiovascular profile despite higher prevalence in the use of statins and anti-hypertensive medications including inhibitors of rein–angiotensin system (RAS) blockers (Table 5). In particular, blood uric acid levels were higher in patients with MS, whereas pulse pressure was elevated in patients with NODAT. After adjusting for the use of allopurinol, differential use of CNIs, and renal function, the presence of MS was associated with 0.46 mg/dL higher in uric acid levels (p < 0.001). In addition, each component of MS contributed 0.24 mg/dL higher in uric acid levels (p < 0.001). Pulse pressure was 3.7 mmHg higher in patients with a diagnosis of NODAT after adjusting for the number of anti-hypertensive medications, age, gender, BMI, differential use of CNIs, and renal function (p = 0.04).

Table 5. Metabolic and cardiovascular profile according to the presence of metabolic syndrome and/or new onset diabetes after transplant.

| None N = 271 | MS N = 230 | NODAT N = 6 | MS/NODATa N = 84 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBGb at last follow-up, mg/dL (SD) | 89.2 (8.3) | 98.5 (12.4) | 108.7 (21.7) | 119.9 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| BMI at last follow-up, kg/m2 (SD) | 26.6 (5.2) | 32.7 (6.8) | 27.5 (8.1) | 34.1 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Change in BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 1.8 (3.3) | 4.0 (4.1) | 0.7 (3.3) | 3.4 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (SD) | 192.8 (42.0) | 183.4 (38.0) | 155.0 (9.9) | 188.0 (49.4) | 0.02 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL (SD) | 142.5 (71.4) | 225.9 (99.2) | 98.5 (33.2) | 250.4 (269.1) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL (SD) | 59.3 (16.6) | 43.8 (12.6) | 57.2 (9.5) | 43.9 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (SD) | 104.6 (34.1) | 94.7 (28.6) | 78.0 (13.9) | 99.2 (36.5) | 0.003 |

| Statins usage, yes (%) | 144 (54.1) | 165 (71.7) | 6 (100) | 68 (81.0) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL (SD) | 6.7 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.8) | 5.6 (2.0) | 7.2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Allopurinol usage, (%) | 28 (10.3) | 40 (17.4) | 0 (0) | 13 (15.5) | 0.11 |

| SBP, mmHg (SD) | 129.9 (17.4) | 133.9 (16.2) | 135.5 (17.0) | 133.9 (21.1) | 0.05 |

| DBP, mmHg (SD) | 75.2 (11.5) | 76.7 (12.2) | 69.5 (10.5) | 71.6 (12.1) | 0.005 |

| PPc, mmHg (SD) | 54.7 (14.7) | 57.1 (14.1) | 66.0 (23.3) | 62.3 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| Anti-HTN meds (SD) | 1.7 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| RASd blocker, yes (%) | 153 (56.5) | 147 (63.9) | 4 (66.7) | 58 (69.1) | 0.13 |

| aMDRD, mL/min (SD) | 52.0 (16.4) | 49.6 (16.6) | 52.2 (9.9) | 53.0 (19.3) | 0.29 |

BMI, body mass index; HDL, high density lipoprotein.

Patients with both diagnosis.

FBG, fasting blood glucose.

PP, pulse pressure.

RAS, rein–angiotensin system.

Discussion

Our study showed that metabolic syndrome and new onset diabetes after transplant are highly prevalent in kidney transplant recipients. Furthermore, the two conditions are closely associated by sharing some but not all pre-transplant risk factors. Elevated body mass index and fasting glucose levels prior to transplantation are risk factors for both conditions, whereas African American race, old age, and hypertension-related ESRD are risk factors for developing NODAT. The weight gain following transplant was associated with the presence of MS but not the development of NODAT.

Metabolic syndrome is present in over 20% of US adults over the age of twenty and predicts the future risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes (15–17). In kidney transplant patient populations, the reported prevalence of metabolic syndrome varies widely from as low as 14.9% to as high as 65%, likely reflecting the difference in populations studied (2, 18–20). The presence of MS is associated with the risk of developing NODAT. Both MS and NODAT are associated with chronic allograft dysfunction, poor graft, and patient survival (2, 6, 19). One recent study found that kidney transplant recipients with MS had significantly higher coronary artery calcification, a risk for coronary artery disease (18). Another group of investigators showed that the presence of MS was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events (21). As cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in kidney transplant patients, accounting for over 50% of deaths, therefore, identifying clinical predictors and/or risk factors for both MS and NODAT before transplant may help early diagnosis of both conditions and provide guidance for appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Our study confirmed the findings of impaired metabolic and cardiovascular profiles in kidney transplant patients affected by either or both conditions and provided a hint that two conditions may impact negatively on cardiovascular risk in different ways. MS was associated independently with reduced renal function and elevated blood uric acid levels, whereas NODAT was associated with elevated pulse pressure. Many studies have linked elevated blood uric acid levels to the risk of cardiovascular events independent of renal function (22, 23). Similarly, elevated pulse pressure was reported to be associated with increased cardiovascular mortality (24, 25).

The use of immunosuppressive medications, such as CNIs and prednisone, negatively impact metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles. However, our study could not demonstrate any association of a particular immunosuppressive agent on either conditions, neither did levels of CNIs between the groups affected the study outcome (data not shown). Similarly, the episodes of acute rejection did not differ among groups and had no impact on the occurrence of MS and NODAT in our study. However, occurrence of acute rejection did negatively impact renal function.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional and retrospective observation of the prevalence of MS. We do not know how many of those patients had MS at the time of transplantation because of the lack of adequate information on all components of MS at the time of transplant. Therefore, we could not determine how many of those patients actually developed metabolic syndrome following transplantation. Thus, the relationship between MS and NODAT can be only seen as an association rather than cause-effect between the two conditions. Second, we did not have reliable information regarding cardiovascular events in this cohort of patients and therefore we were unable to assess the impact of MS on cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, our study did not address the effect of MS and NODAT on patient survival, the most important endpoint of any study of cardiovascular risk.

In summary, we found that MS is highly prevalent and closely associated with NODAT in previously non-diabetic stable kidney transplant recipients. Both conditions are associated with impaired metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles. Early detection of MS prior to transplantation may help us to understand its impact on the risk for the subsequent development of NODAT. Target therapeutic intervention could be instituted at an early stage.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Marsha Salley for her careful review of the revised manuscript.

References

- 1.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrini E, Delgado P, Bigo C, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on graft function and survival after cadaveric renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:134–42. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Midtvedt K, et al. Metabolic cardiovascular syndrome after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1047–52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuypers DR, Claes K, Bammens B, Evenepoel P, Vanrenterghem Y. Early clinical assessment of glucose metabolism in renal allograft recipients: diagnosis and prediction of post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2033–42. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Gilbertson D, Matas AJ. Diabetes mellitus after kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:178–85. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Leivestad T, et al. The impact of early-diagnosed new-onset post-transplantation diabetes mellitus on survival and major cardiac events. Kidney Int. 2006;69:588–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosio FG, Kudva Y, van der Velde M, et al. New onset hyperglycemia and diabetes are associated with increased cardiovascular risk after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2415–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland M, Gatault P, Doute C, et al. Immunosuppressive medications, clinical and metabolic parameters in new-onset diabetes mellitus after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2008;21:523. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(Suppl 1):S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Nathan DM, D'Agostino RB, Williams K, Haffner SM. Prevalence and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in the San Antonio Heart and Framingham Offspring Studies. Diabetes. 2003;52:2160. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Giles WH. Trends in waist circumference among U.S. adults. Obes Res. 2003;11:1223. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:385. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinola-Klein C, Rupprecht HJ, Bickel C, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular prognosis. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1623. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adeseun GA, Rivera ME, Thota S, Joffe M, Rosas SE. Metabolic syndrome and coronary artery calcification in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2008;86:728. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181826d12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vries AP, Bakker SJ, van Son WJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with impaired long-term renal allograft function; not all component criteria contribute equally. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishikawa H, Nishimura K, Kato T, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:181. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rike AH, Mogilishetty G, Alloway RR, et al. Cardiovascular risk, cardiovascular events, and metabolic syndrome in renal transplantation: comparison of early steroid withdrawal and chronic steroids. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:229. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971-1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2000;283:2404. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodov Y, Chouraqui P, Goldenberg I, Boyko V, Mandelzweig L, Behar S. Serum uric acid for risk stratification of patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiology. 2009;114:300. doi: 10.1159/000239860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benetos A, Rudnichi A, Safar M, Guize L. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular mortality in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1998;32:560. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domanski M, Norman J, Wolz M, Mitchell G, Pfeffer M. Cardiovascular risk assessment using pulse pressure in the first national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES I) Hypertension. 2001;38:793. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.092966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]