Abstract

The assembly of functional synapses requires the orchestration of the synthesis and degradation of a multitude of proteins. Protein degradation and modification by the conserved ubiquitination pathway has emerged as a key cellular regulatory mechanism during nervous system development and function (Kawabe and Brose, 2011). The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is a multi-subunit ubiquitin ligase complex primarily characterized for its role in the regulation of mitosis (Peters, 2002). In recent years, a role for APC/C in nervous system development and function has been rapidly emerging (Stegmuller and Bonni, 2005; Li et al., 2008). In the mammalian central nervous system the activator subunit, APC/C-Cdh1, has been shown to be a regulator of axon growth and dendrite morphogenesis (Konishi et al. 2004). In the Drosophila peripheral nervous system (PNS), APC2, a ligase subunit of the APC/C complex has been shown to regulate synaptic bouton size and activity (Van Roessel et al., 2004). To investigate the role of APC/C-Cdh1 at the synapse we examined loss-of-function mutants of Rap/Fzr (Retina aberrant in pattern/Fizzy related), a Drosophila homolog of the mammalian Cdh1 during the development of the larval neuromuscular junction in Drosophila. Our cell biological, ultrastructural, electrophysiological, and behavioral data showed that rap/fzr loss-of-function mutations lead to changes in synaptic structure and function as well as locomotion defects. Data presented here show changes in size and morphology of synaptic boutons, and, muscle tissue organization. Electrophysiological experiments show that loss-of-function mutants exhibit increased frequency of spontaneous miniature synaptic potentials, indicating a higher rate of spontaneous synaptic vesicle fusion events. In addition, larval locomotion and peristaltic movement were also impaired. These findings suggest a role for Drosophila APC/C-Cdh1 mediated ubiquitination in regulating synaptic morphology, function and integrity of muscle structure in the peripheral nervous system.

INTRODUCTION

The assembly of functional synapses requires the balance among synthesis, sequestration and timely degradation of a multitude of proteins. In recent years a growing body of evidence has suggested a critical role for the Ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) in the establishment of functional neuronal circuits (Speese, 2003; Kawabe and Brose, 2011). Ubiquitination of specific proteins at pre- and post-synaptic regions followed by degradation by the UPS provides a powerful molecular regulatory mechanism during neuronal development (Haas and Broadie, 2008). Ubiquitination involves the covalent addition of the 76 amino acid protein ubiquitin by a ubiquitin ligase to the N-terminus of the identified substrate protein. Polyubiquitination results in targeted protein degradation by the 26S proteosome, while mono-ubquitination leads to protein modification and regulation of protein function (Schnell and Hick, 2003). Ubiquitinated proteins are recognized by a diverse variety of cellular machinery including UPS, DNA repair, replication, mitosis, and endosomal traffic (Hick and Dunn, 2003; Glickman and Ciechanover, 2002). Ubiquitination is ATP dependent and typically involves the function of three ligases. Briefly, the E1-activating enzyme sequesters ubiquitin and activates it by adding an ATP before transferring it to an E2-conjugating enzyme. Next, the E2 binds directly to the substrate protein or to an E3-ligase that is already attached to the substrate protein. Finally, the E3 ligase protein removes the ubiquitin from E2 and adds it to the substrate protein (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Deshaies and Joazeiro, 2009).

Studies during the past decade have shown that the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, the Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) plays an important role in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity (Stegmuller and Bonni, 2005). APC/C is an evolutionarily conserved multi-subunit ubiquitin ligase complex that was originally characterized primarily for its critical role during mitotic cell cycle progression. APC/C facilitates the ubiquitination and timely degradation of key mitotic regulators such as cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases and securing (Peters 2002). APC/C consists of at least 11 core subunits and Targeting of protein substrates and the subsequent activation of APC/C for ubiquitination is dependent on two proteins with WD (Trp-Asp) repeat domain, Cdh1 and Cdc20 Cdh1 and Cdc20 function during distinct stages of the mitotic cell cycle and target different substrates. Cdh1 mediates the recruitment of the substrate proteins to the APC/C via the interaction of its WD domain with either the D-box, KEN-box or the A-box motifs on the substrate (Kashevsky et al., 2002; Peters 2002).

A role for APC/C in nervous system development was triggered by the initial discovery that APC/CCdh1 is largely expressed in post-mitotic neurons in the mammalian brain and to a lesser extent in skeletal muscle tissue (Gieffers et al. 1999). More recent studies have firmly established an essential role for APC/C in mammalian neuronal development and synaptic plasticity and components of the APC/C have been localized to the pre- and post-synaptic regions. (Konishi et al. 2004; Stegmuller and Bonni 2006; Kim et al., 2009). In the Drosophila, Neuromuscular junction (NMJ), van Roessel et al. (2004) showed that in loss-of-function of the E3 ligase subunit, APC2 (morula) leads to a decrease in the number of synaptic boutons, increase in glutamate receptors expression levels, and abnormally strong synaptic transmission at the larval NMJ. Similarly in C. elegans, the APC/C has been shown to regulate the number of GLR-1 receptors in the postsynaptic cell by directly targeting proteins involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Juo and Kaplan 2004). Post-synaptically UPS also in regulates glutamate receptor levels through regulating endocytosis of postsynaptic density (PSD) scaffolding proteins. Although it is now well established that APC/C regulates a multitude of cellular processes through the ubiquitination of variety of substrates, the full extent of the nature and identity of its substrates is not fully understood. Rap/Fzr is the Drosophila homolog of the mammalian Cdh1 (Sigrist and Lehner, 1997; Jacobs et al., 2002; Pimentel and Venkatesh, 2005).

Employing genetic interactions studies and bioinformatic analyses we identified 39 cellular proteins as potential substrates of the Drosophila Cdh1/Rap/Fzr (Kaplow et al., 2007). To further understand the role of Cdh1 at the synapse, we have examined the effects of loss-of-function of Drosophila Cdh1/Rap/Fzr at the larval neuromuscular junction. Our finding suggests that the Drosophila Cdh1/Rap/Fzr, the activating subunit of APC/C regulates synaptic morphology, muscle structural integrity and larval locomotory behavior. Using loss-of-function alleles we were able to determine changes in bouton morphology, electrophysiology and larval locomotion ability. The data presented here suggest an essential role for Drosophila Cdh1/Rap/Fzr in synaptic structure and function at the NMJ.

METHODS

Drosophila culture and strains

Drosophila was reared in the laboratory at 22 C on standard cornmeal agar medium. The following mutant rap/fzr flies were used: rapE2, rapE4, rapE6, rapX-2, rapX-3 and w, rap3. The isolation and characterization of these mutant alleles have been previously described (Jacobs et al., 2002; Karpilow et al., 1989). Null alleles of rap/fzr are embryonic lethals, thus mutants that were used here are all hypomorphic (partial loss-of-function) alleles.

Immunohistochemistry

Wandering larvae were dissected in calcium-free media HL3.1 solution (Fergestad and Broadie, 2001) and fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde for 25 minutes (Paraformaldehyde in Phosphate Buffer Solution). Washes and antibody incubations were performed in Phosphate Buffer Solution with Triton-X (0.1%). Anti-Dlg (disc-large, post-synaptic NMJ marker from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB, University of Iowa), anti-GluRIIa (glutamate receptor IIa, postsynaptic NMJ marker from DHSB and anti-BRP (bruchpilot, presynaptic NMJ marker also from DSHB), were used at 1:5. Secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC (Jackson Immunochemicals), Rhodamine (Jackson Immunochemicals), or Cy5 (Invitrogen) were used at 1:100. Cy5-conjugated phalloidin (25 nM, Molecular Probes) was used to stain muscles at 1:1000 and anti-HRP-Rhodamine Red-X (Jackson Immunochemicals) was used to stain neuronal membrane at 1:100. All imaging was performed using a LSM 510 Confocal Laser Scanning System (Carl Zeiss). Anti-Dlg and anti-HRP positively stained boutons counts were performed on muscle 6 and 7, abdominal segment A3. Mann-Whitney-U test was used to derive the p-value and significance. Among all of the mutant alleles, rapX-3 and w, rap3 were looked at more extensively because of the severity in their phenotypes.

Quantitative Immunofluorescence

To identify changes in immunofluorescence intensity, control and mutant larvae were dissected and stained together. Immunohistochemistry was performed was described above, using anti-BRP and anti-GluRIIa antibodies. Segment A3 was observed for each mutant and control. Laser intensity levels were kept low and used at a magnification of 40X. Plug-in software from Image-J was used to define level of saturation for each image using an arbitrary intensity threshold. Mean intensity values of wild-type and mutants were identified.

Quantitative Immunofluorescence

To identify changes in immunofluorescence intensity, control and mutant larvae were dissected and stained together. Immunohistochemistry was performed was described above, using anti-BRP and anti-GluRIIa antibodies, and segment A3 was observed for each mutant and control. Laser intensity levels were kept low and used at a magnification of 40X. Plug-in software from Image-J was used to define level of saturation for each image using an arbitrary intensity threshold. Mean intensity values of wild-type and mutants were then identified. Student’ t-test was used the statistical analysis of the data. Anti-HRP staining fluorescence intensity was used as an internal control.

Method of Transmission Electron Microscopy

To prepare ultrathin sections for transmission electron microscopy, the dissected larva muscle samples were first chemically fixed at 4 °C for 24 hours. The fixative measured a pH of 7.4 and contained 2.5 % glutaraldehyde, 2 % paraformaldehyde, 1 % low molecular weight tannic acid in 0.1 M Na Cacodylate. The samples were washed with 0.1 M sodium Cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in Cacodylate buffer with 1.5% K4 [Fe (CN)6], for 90 min on ice in darkness. The samples were then washed with Cacodylate buffer and incubated with 1% tannic acid in Cacodylate buffer for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were washed with distilled water and further incubated with 1% osmium tetroxide water solution for 30 min on ice and in darkness. After the osmium treatment and distilled water wash, the samples were dehydrated with alcohol with a gradual increase in concentration from 30 % to 100%. The samples were subsequently washed with 100% propylene oxide for 5 min before embedded in resin (made of 20 ml of EMbed 812, 9 ml of DDSA and 12 ml of NMA). In the process of embedding, the samples were first immersed for a few hours in each of 30% and 70% of resin in propylene oxide at room temperature, further incubated in pure resin and then transferred into activated resin (10 ml of resin activated with 0.18 ml of DMP-30) in embedding capsules. The resin-containing samples were polymerized at 67 °C for 72 hours. After polymerization, cross sections of ~ 70 nm were cut at the center of muscles 6 and 7, segments A2 through A6, using LKB Ultratome (LKB-Produkter AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The sections were set on copper grids and stained with 0.5% lead citrate basic solution for 20 min. The stained sections were examined using Philips CM12 transmission electron microscope) operated at 80 KV. Images were taken with a Gatan 4K X 27K digital camera (Pleasanton, CA). Synaptic vesicles located within 50 nm from the presynaptic membrane were considered as potentially docked at release sites (Tartaglia et al., 2001). The following chemicals were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA): Low molecular weight tannic acid (C14H1009)n), paraformaldehyde solution, glutaraldehyde aqueous solution, osmium tetroxide aqueous solution, sodium cacodylate butter, propylene oxide, EMbed 812, DDSA, NMA and DMP-30. Mann-Whitney-U test was employed for the statistical data analysis.

Electrophysiology

Wandering Third- instar larvae were dissected in Ca2+ free HL3 solutions buffered at pH 7.2 (Stewart et al., 1994; Robinson et al. 2002) and excitatory junctional potentials (ejps) were recorded in HL3.1 solution (Feng et al., 2004) with CaCl2 as specified in Results section. Muscle segments A3, A4, and A5 of muscles 6 and 7 were used using sharp intracellular electrodes (20–50 MΩ) farbricated from borosilicate glass capillaries and filled with 3 M KCl solution. To evoke ejps, severed nerve bundles were stimulated at 0.5 Hz, using a suction electrode (10-μm inner diameter) connected to a stimulus isolation unit. Data was acquired through a direct current amplifier (model M701 microprobe system; WPI, Sarasota, Florida, USA, and an additional custom-built amplifier). Recordings with the resting potential shallower than −55mV were rejected from analyses. Data analysis was done using Axograph X and statistical analyses was done using Student’ t-test.

Muscle Degeneration

Immunocytochemistry was performed on third-instar larva as per the methods described in the immunocytochemistry methods section. Phalloidin and DAPI were used to stain muscle and muscle nuclei respectively of CS and w, rap3. Images were taken with Zeiss Confocal Microscope and statistical analysis of muscles were performed using Prism 5 software. Students’ t-test was used to derive p-value and significance.

Larval Behavioral Crawling Assays

Larval behavioral crawling assays were performed according to Daubert and Condon (2007). Adult flies were allowed to lay eggs in standard fly food vials, after which the adults were removed. The larvae were grown until they were foraging third instars (72–78 hours pos-hatching). 20–25 larvae of each strain were collected using a moistened paintbrush and underwent three 1mL 7-minute water washes in order to remove any yeast residue. After removing the dirty water with a micropipette, the larvae were allowed to recover for ten minutes on a clean, dry 35 x 10-mm Petri dish with the lid on. Prior to testing the larvae, a 5 mm hole was made in the center of a 100 x 15-mm agar plate. Cold baker’s yeast-water paste was applied to the center of the plate until it filled to the level of the agar. After placing the plate underneath a videorecorder (Apple iSight) the larvae were carefully laid out 5mm from the plate’s it using a spatula and paintbrush. Approximately 110–150 of each control and mutant strains were tested in groups of 20–25. The plates were each recorded for thirty minutes at room temperature in a darkroom, in order to prevent their negative larval phototaxis from interfering with their migration towards the yeast. Ratios comparing the number of larvae that made it to the yeast paste to those did not were used as a method of comparison. Statistical analyses of was done using the Student’ t-test.

Larval Peristaltic Contraction counting Assay Protocol

Agar plates were made using 12.5% Ultra-pure Agarose and stored at 4°C. An agar plate was incubated at 30°C for 15 min. A 12 well plate was used for washing the larvae, with 6 wells filled with 500μL d.i. water, and 6 wells with 500 uL 15% sucrose solution. Late third instar larvae in the wandering stage were identified as crawling on the side of the bottle (not submerged in the food). They were removed from the bottle using a paintbrush, and about 4 were placed in each of the sucrose wells. The well plate was put on a shaker for 1 wash (7 minutes). Using the paintbrush, the larvae were then transferred from the sucrose wells to the d.i. water wells, and returned to the shaker for 2 washes (14 minutes). An individual larva was removed from a well, placed on the agar plate, and allowed to acclimate for 30 seconds. The number of peristaltic contractions was then counted for 2 minutes. If the larva was still alive but no contractions were observed, it was recorded as ∞ time, and the trial was redone with a different larva. 100 larvae were observed for each mutant strain. Student’ t-test was used in the data analysis.

Larval Locomotion Analysis

Further locomotory studies were performed on Third-instar “wandering” larvae using Multi-Worm Tracker (Janelia Farms) software. MWT is a set of software that tracks, in real time, small movements in high-contrast against a static background. Larvae were first washed in dH2O and then placed on thinly coated 1.5% agar gel plates, while Nikon camera was used to image the plates. Up to five larvae at a time were allowed to remain on the plate for 62 seconds while the software captured their images. After 62 seconds, the larvae were discarded and five new larvae were plated on the same agar plate. Each trial contained approximately five larvae and total of 15 trials were used for each rap/fzr mutant. Data were compiled in Excel and analyzed in Prism 5. Data produced included at speed, length, angular speed and kink. Speed refers to the speed of the objects in mm/second. Angular speed was measured in radians/second of objects; this is calculated over the same interval as speed, but reports the greatest difference in angle between primary axes over that time. Length refers to the distance spanned by objects along their major axis (defined to be the axis of a least squares fit), in mm. Finally, kink, which was defined as the angle in radians between the line from the first to third point of the skeleton and the fourth through last points. Student’ t-test was used in the statistical data analyses.

RESULTS

Abnormal bouton morphology in rap/fzr neuromuscular junctions

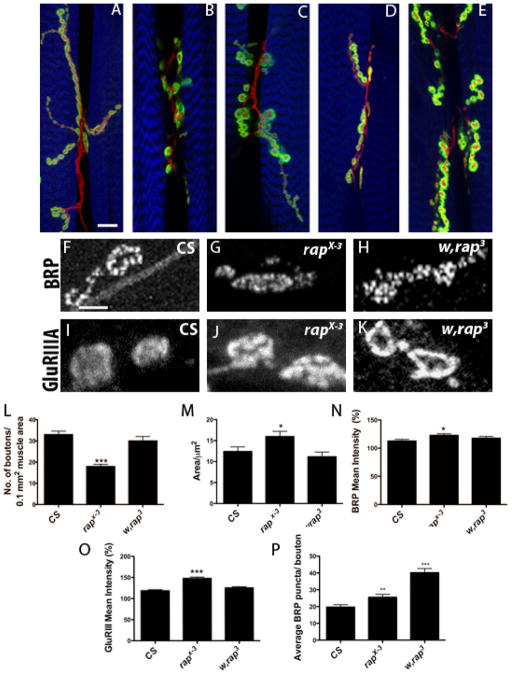

To study the role of Drosophila-Cdh1 (Rap/Fzr) in the regulation of synaptogenesis at the NMJ, we first examined the bouton morphology of loss-of-function rap/fzr mutants. We examined loss-of-function mutant alleles rap E2, rapE4, rap E6, rap X-2, rap X-3 and w, rap3 previously generated in our laboratory (Jacobs et al., 2002; Karpilow et al., 1989). Wild type (CS) boutons appeared oval in shape with relatively smooth membrane edges and roughly equal spacing between each bouton, all of which formed normal branching patterning axons that innervate the muscles. In the mutant alleles the general morphology of the boutons changed, becoming more erratic in shape ranging from a circular oval shaped with smaller blebs branching off that single oval, as well as boutons with very misshapen membranes (almost a ‘wavy’ appearance). In general, rap/fzr mutants’ boutons appear larger in size (Figure 1A–E).

Figure 1. rap/fzr mutants show significant changes in bouton morphology.

(A) CS, (B) rapE6, (C) rap X-2, (D) rap X-3 (E) w, rap3;

(A–E) Loss-of-function rap/fzr mutants exhibit changes in bouton morphology at the NMJ as seen in this composite of rap/fzr mutant alleles with various antibodies. Sample confocal images of larval NMJs from muscle segment 3 (muscles 7 and 6) stained with HRP (Red), phalloidin (Blue), and either Dlg, GluRIIa or BRP (green). When compared to CS, rap/fzr mutants rapE6, rap X-2, rap X-3 and w, rap3 alleles exhibit fewer numbers of boutons. In addition, boutons tend to be more oblong and misshapen with less smooth postsynaptic density staining, especially with w, rap3. w, rap3 also seen here having enlarged Dlg staining. (F–H) BRP staining not only showed increase in staining intensity but also increase in the number of puncta in rapX-3 and w, rap3. (I–K) Similarly, In the GluRIIa staining, puncta appear to have greater intensity particularly in rapE6 and w, rap3. (L) Comparison of NMJ boutons number at the NMJ show decrease in rap/fzr mutants, rapE2, rapE4, rapE6, rap X-2 and rap X-3 n=29, p<0.0001. w, rap3 did not show decrease in boutons. (M) There is a significant increase in size in rapE4 n=29, p<0.0005, rapX-2 n=29, p<0.05 and rapX-3 n=29, p<0.05. The other alleles also show an increase in size but, however, are not significant. Only w, rap3 shows no difference in size compared to wild type. (N) Fluorescent intensity of BRP significantly increased in rapX-3 n=11, p<0.05 and not significant in w, rap3 p<0.186, n=11. (O) GluRIIa staining is also significantly increased in rapX-3 p<0.0001, n=11 and not significantly increased in w, rap3 p<0.25, n=11. (P) Average BRP puncta count per bouton are significantly increased, rapX-3, n=30, p<0.001 and w, rap3 n=30, p<0.001.

In all of the rap/fzr mutants examined the bouton numbers were decreased (Table 1. Mann-Whitney-U tests confirmed that for all of at p<0.0001). Our data on bouton size (Figure 1M) shows an increase in average bouton area compared to Wild type (12.39 ± 6.08, n=29), rapX-3 (15.9 ± 6.67, n=29), rapE4 (19.4 ± 7.24, n=29, p<0.0005, (data not shown). While w, rap3 shows no significant difference in size compared to wild type, images taken of w, rap3 show boutons grossly misshapen boutons, their postsynaptic density convoluted and thickened, making the process of counting and defining the area difficult to accurately quantify. This mutant amorphism demonstrates that Rap/Fzr also works to regulate the pathways involved in bouton morphology. The number of branch networks generated during synaptogenesis was not significantly affected in the rap/fzr mutants (data not shown).

Table 1. Rap/Fzr mutants show decrease in bouton number.

Comparison of NMJ boutons number at the NMJ show decrease in rap/fzr mutants, rapE2, rapE4, rapE6, rapX-2 and rapX-3; w, rap3 did not show decrease in boutons. (* Indicates standard deviation).

| Mutant Allele | Bouton Number ± S. D | n | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS(Control) | 32.95± 7.51 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| rapE2 | 15.7± 3.79 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| rapE4 | 14.6± 4.68 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| rapE6 | 13.6± 5.48 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| rapX-2 | 17.2± 7.71 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| rapX-3 | 1.9± 3.55 | 29 | P<0.0001 |

| w, rap3 | 30. ± 8.03 | 29 | n.s |

To test whether there were changes in proteins associated with vesicle release, two antibody markers were used, anti-Bruchpilot (BRP) and anti-glutamate receptors type-IIA (GluRIIa) and assessed the changes in fluorescent intensity and puncta staining (Figures 1F–K). The average level of intensity of clusters were then quantified (Figures 1N–P). rapX-3 mutants showed significant changes in the intensity of anti-BRP (CS 112.6 ± 2.98 n=11, rapX-3 122.8 ± 2.88, n=11, p<0.05) and GluRIIa staining (CS 118.6 ± 2.452, n=12; rapX-3 147.8 ± 3.347, n=12, p<0.0001). In addition, BRP puncta were also significantly increased in rapX-3 and w, rap3 (Figure 1P; n=30, p<0.001). w, rap3 saw only a slight change in anti-BRP and anti-GluRIIa intensity. Together, these results indicate changes in vesicle release machinery as well as changes to postsynaptic receptor density. It is not yet clear whether rap/fzr affects both of these mechanisms or if one is a consequence of the other. Our results demonstrate that rap/fzr regulates size and number.

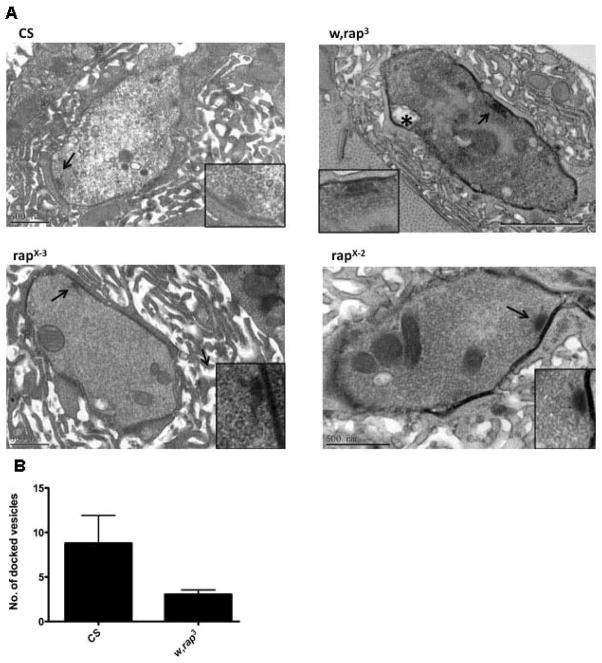

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) reveals presynaptic changes in rap/fzr mutants

Ultrastructural analysis by TEM was conducted to examine the synaptic boutons and subsynaptic reticulum in wild type and mutant larvae (Figure 2A). The size of synaptic vesicles is similar in mutants and CS (CS: 43.2±7.2 nm, mean and SD, n=320; rapX-3: 44.4±9.6 nm, n=290; w, rap3: 42.3±9.1 nm, n=245). Among the mutants examined, rapE2 and rapE6 do not appear to be dramatically different from wild type (data not shown). Mutant rapE4 has larger terminals than CS but the same density of vesicles (data not shown). However, boutons of w, rap3 have significantly less synaptic vesicles than CS terminals (p=0.035, Mann-Whitney rank sum test). In 15 bouton images from w, rap3 mutants, and 345 synaptic vesicles were identified compared to 439 vesicles in 6 images of CS boutons. While the total vesicle number reflects the storage pool of synaptic vesicles, the vesicles docked to the presynaptic membrane determine the synaptic release probability.

Figure 2. Transmission electron microscopic images of neuromuscular junctions in wild type larvae and mutants.

(A) Images of synaptic boutons from muscle fibers 6 and 7 from wild type larvae (CS) and three mutants (w, rap3, rapX-2 and rapX-3). Within each bouton, a presynaptic dense body is indicated with an arrow. Vacuoles (marked with *) were observed more frequently in w, rap3 boutons. Subsynaptic reticulum can be seen around the boutons. Calibration bars: 50 nm for CS, rapX-2 and rapX-3, 100 nm for w, rap3. (B) Histogram of docked vesicles on the presynaptic membrane. Boutons in w, rap3 mutants have significantly fewer docked vesicles than CS boutons (p<0.05, n=15 for w, rap3, n=6 for CS).

We considered potentially docked vesicles to be vesicles within 50 nm of the bouton membrane (Tartaglia et al., 2001) for boutons in CS, rapX-3 and w, rap3. The results are summarized in Figure 2B. On average, each w, rap3 bouton has 3.4±2.7 potentially docked vesicles, which is less than 11.0±6.6 vesicles in CS boutons (p=0.004, Mann Whitney rank sum test). However, it is possible because some terminals with no vesicles were missed due to the lack of vesicles, and therefore we were unable to quantify the vesicle size. In addition, we counted vesicles that were fused to the presynaptic membrane, which is described as vesicle bodies within 5μm from t-bars (Atwood et al., 1993). We found a significant decrease in the number of fused vesicles in the w, rap3 mutant and slightly decreased in rapX-3 (Figure 3B). We also see changes in SSR and postsynaptic density in rap/fzr mutants.

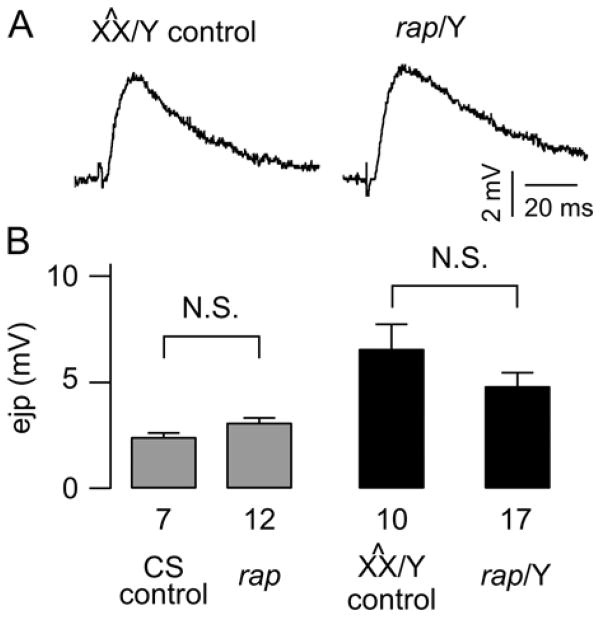

Figure 3. No detectable alterations in nerve-evoked ejps in rap mutant larvae.

(A) Sample ejp traces from rap/Y and X^X/Y control lines. (B) No significant differences in ejp amplitudes between rap and CS or X^X/Y background control lines. Left panel: the rap mutant lines (rapE2, rapx-2, rapx-3, and rap3) and the CS control. Right panel: rap mutant lines (rapx-3, rapx-2, and rap3) backcrossed to X^X/Y. SEM and the sample numbers (NMJs) are indicated. Data from different alleles were combined since their phenotypes were consistent. External Ca2+ concentration was 0.15 mM.

To assess the availability of synaptic vesicles for immediate release, we counted vesicles that are within 50 nm of the axon terminal membrane. A total of 34 axon terminals on muscle cell 6 and cell 7 were examined for wild type (CS); w, rap3 and rap X-3 larvae, one section for each terminal. Compared with wild type terminals, terminals in w, rap3 mutants have significantly less synaptic vesicles within 50 nm of the terminal membrane (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). No significant difference was found between terminals in rap X-3 and CS. The reduced vesicle supply of vesicles in w, rap3 buttons may indicate a reduction in synaptic vesicle formation or an increase in vesicular release the latter is consistent with the increased synaptic transmission in w, rap3 mutants as described below.

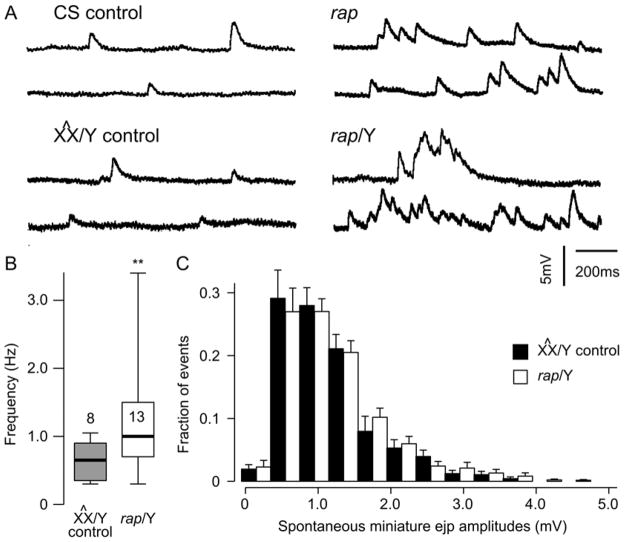

Changes in EJP at the rap/fzr neuromuscular junction

To understand the role of APC/CRap/Fzr/Cdh1 in synaptic transmission, we carried out electrophysiological experiments with rap/fzr mutants. Recordings of evoked response recorded from rap/fzr mutants found that there was no significant difference rap (rapE2, rapx-2, rapx-3 and w, rap3) and CS or X^X/Y background control lines (Figure 3). Data from different alleles were combined since their phenotypes were consistent (CS= 7 and rap/fzr n=12; X^X/Y n=10 and rap/fzr/Y n=10). However, we did find that some rap/fzr mutants exhibited bursting activity (rapX-2), while majority of cells exhibited increased frequency of spontaneous miniature ejps (Figure 4A). Amongst the rap/fzr mutant population there exists unusually large variability of spontaneous miniature ejp frequencies (p<0.01) (Figure 4B). Similarly the size of the amplitude of spontaneous miniature ejps in rap/Y compared to X^X/Y control (Figure 4C). This evidence suggests that Rap/Fzr plays a significant role in spontaneous synaptic vesicle release. The external Ca2+ concentration in which all the recordings took place in was at 0.15 mM. We backcrossed our rap/fzr stock to create an additional control stock to which we could compare electrophysiological changes.

Figure 4. Abnormal spontaneous discharges in rap mutants.

(A) Sample traces from CS and X^X/Y controls and the corresponding rap. Note that bursting activity was observed in some rap NMJs (lower right, rapx-2) while majority of cells exhibited increased frequency of spontaneous miniature ejps (upper right, rap3). (B) Unusually large variability of spontaneous miniature ejp frequencies among different rap NMJs. ** indicates p < 0.01; F-test. (C) Similar size of spontaneous miniature ejps in rap/Y compared to X^X/Y control. Error bars indicate SEM. Number of NMJs examined are 8 for X^X/Y control and 13 for rap/Y. All samples presented in B and C are combined data from three rap alleles (rapx-3, rapx-2, and rap3) backcrossed to X^X. Consistent phenotypes were observed in other rap lines in the CS background also (see A).

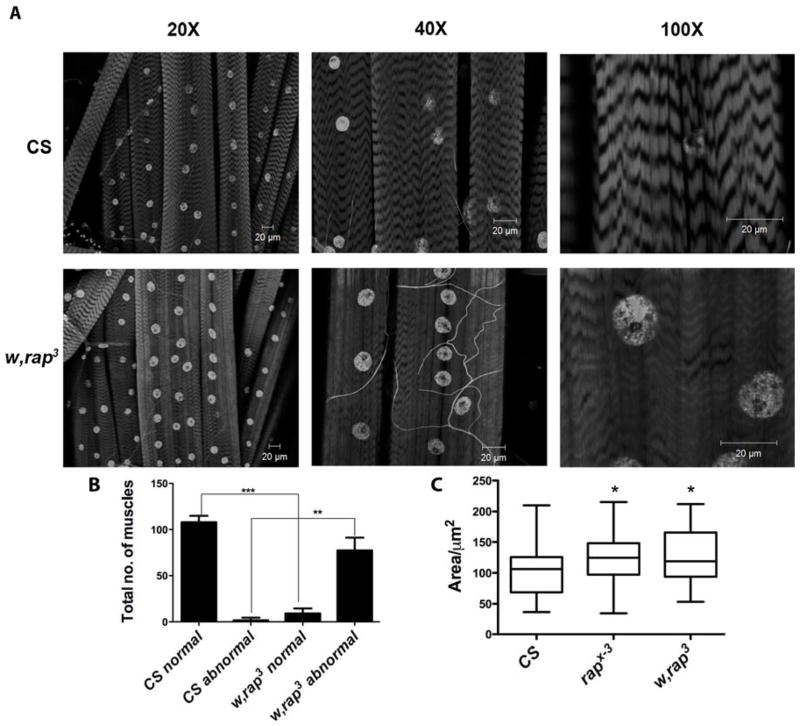

Muscle Degeneration

APC/C-Cdh1 has been shown to be present in skeletal muscle tissue, however its involvement in muscle structure /function is largely unknown (Gieffers, C. et al. 1999). To test for its possible functional role in the muscle, we examined muscle fiber organization in loss-of-function rap/fzr mutants. The allele, w, rap3 presented dramatic phenotypic changes in muscle fiber organization (Figure 5A). wild type (CS) muscles contained clearly visible, repeating sarcomere units. The darker staining regions are associated with A band that contain overlapping thin and thick filaments. I bands are the segments in between each A bands. All were found to be normal in the wild type. w, rap3 at 20X magnification, contained patches of similar organization found in wild type at 20X magnification. However in the majority of the muscle, these structures were not present and exhibited a disappearance of I bands and blending of A bands, an appearance that looked ‘rubbed-out’, Upon closer inspection at a magnification of 100X, the muscle in w, rap3 provides further evidence of the changes in these specialized structures associated with sarcomeres. We observed that the majority of the muscles afforded these band changes this way in w, rap3 mutants (CS total muscles n=329, normal muscles were 108 ± 7; WT abnormal muscles 1.67± 2.89; w, rap3 total muscles n=260, normal muscles were 9 ± 5.57, abnormal muscle 77.67±13.58). The total number of abnormal muscles was significantly increased in w, rap3 (Figure 5B). Additionally, the total numbers of normal muscles was significantly decreased. This decrease indicates that rap/fzr is necessary in normal development of muscle fiber structure and maintenance. We also show a significant increase in the size of the muscle nuclei (Figure 5C). The total area (μm2) was increased in rapX-3 when compared to CS (n=35, p<0.0156) and w, rap3 (n=35, p<0.0115) using Mann-Whitney t-test. This is consistent with the well established role of APC/C-Cdh1 during mitotic cell cycle, wherein Cdh1 facilitates exit from the M phase and promotes endoreplication. This results in multiple rounds of DNA replication without the ensuing nuclear division.

Figure 5. Muscle phenotype in w, rap3 mutants.

(A) Confocal images of larval muscles stained with DAPI and Phalliodin These images show changes in sarcomere patterning in w, rap3 when compared to wild type (CS). There is significant disruption in the structure of I and A bands, their boundaries are not distinct and appear amorphous. We also see increase in the number of nuclei staining. (B) This figure demonstrates the increase of number of muscles that exhibited degeneration in sarcomere structure in rap/fzr mutants. Comparison of CS normal (n=3) and w, rap3 normal (n=3), p<0.0001. The number of abnormal muscles in w, rap3 was also increased in comparison to CS (p<0.0089). (C) Muscle nuclei were larger in area2 for both rapX-3 (n=35, in 3 different larvae) p<0.0156 and w, rap3 (n=35, in 3 different larvae) p<0.0115) compared to CS.

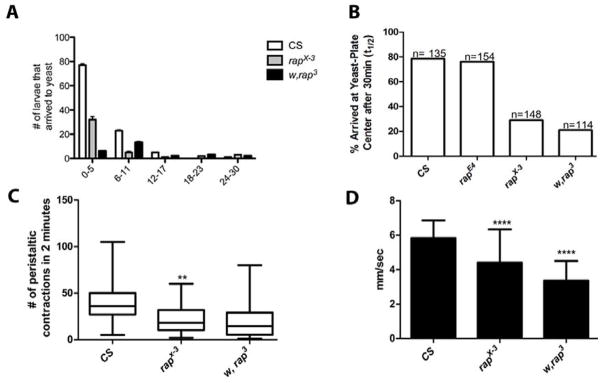

Rap/Fzr mutants exhibit impaired larval locomotion

Crawling

To test whether rap/fzr mutants show impairments in locomotion due to previously described changes in synapse physiology, we conducted three independent locomotion assays. First, Larvae were recorded as they race towards a chemo-attractant (yeast) stimulus. To ascertain that the impaired mobility was not due impaired neuromuscular defects and not just a chemosensory response defect, we used a second test. In this test, we observed and manually recorded the number of peristaltic movements on an agar plate. Lastly, we quantified larval turning rate and velocity during wandering behavior through the use of Worm-tracker video analysis. This permits for a high-throughput analyses and simultaneous comparison of different genotypes, video archiving, and detection of defective locomotion in our mutants. In all the three assays locomotion behavior also appears to be greatly affected in rap/fzr mutants. We observed significant locomotory deficiencies in the mutants that exhibited severe changes in physiology as described above, further implicating Rap/Fzr in synaptic development and neural transmission. All of the mutant alleles tested exhibited longer crawling times and in most cases ceased their movement all together. The distribution of the number of larvae that arrived at the yeast center within 30 minutes was calculated for each strain, in intervals of six minutes (Figure 6A, P<0.05). The majority of the wild type (CS) larvae arrived to the yeast in the first five minutes with very few arriving at later times. All of the rap/fzr alleles tested had significantly fewer number of larvae arriving within the first ten minutes, with w, rap3 having the fewest larvae arriving at any of the time intervals. We show that the ratio of the number of larvae arriving at the yeast center versus those that did not was significantly different compared to wild type. The most severe mutants that never reached the yeast center were noted and ratio to those that did was calculated. In comparison to CS, these strains exhibited significantly lowered rates of larval arrival. This decreased arrival rate implies a decrease in mobility in severe mutants. Wild Type (CS) had greatest number of larvae that made it to the yeast paste, with 3.65:1, or 78.5%, of the total larvae arriving to the food within thirty minutes. rapE4 larvae presented a 3.16:1 ratio, with 76.0% arriving within the allotted time. rapX-3 larvae presented a .40:1 ratio, with only 29% of them arriving to the yeast within thirty minutes. w, rap3 mutants were least able to arrive to the yeast, with only .23:1, or 21% of them arriving within thirty minutes (Figure 3B).

Figure 6. rap/fzr mutants show deficits in larval locomotion.

(A) & (B) Show the distribution of larvae that reached the chemoattractant center of an agar filled petri dish larvae after a 30-minute period. The majority of CS larvae reached the yeast center within 0–5 minutes, while the other mutants range from 11–30 minutes. All mutants were significantly slower, p<0.05, rapE4 (n=154), rapX-3 (n=148), w, rap3 (n=114). (C) Number of peristaltic contractions by different mutant strains but relative to CS, contracted far less. In comparison to wild-type, CS n=100, mutants ranged in severity with rapx-2 being the most impaired in locomotion (n= 100, p<0.0001), followed by rapx-3 n= 100, p<0.0001 and w, rap3 n=100, p<0.0001. The number of peristaltic contractions is significantly decreased in the most severe rap/fzr mutants. (D) “Worm Tracker” revealed that rap/fzr were significantly impaired in locomotion behavior by having a slower velocity than CS, rapX-3 n= 87, p<0.0001 and w, rap3 n= 91, p<0.0001.

Peristaltic contractions

To further investigate larval locomotion, we recorded the number of peristaltic contractions of third instar larvae in the wandering stage of all the rap/fzr mutants and wild type. Peristaltic contractions alternate between shortening and lengthening phases in a rhythmic motion that allow the larva to move, which can be easily observed by the naked eye. Although the larvae generally wandered in random directions, wild-type larvae on average contracted more frequently than any of the mutant strains. Wild type larvae began moving almost immediately after being placed on the plate; while rap/fzr mutants seemed required more time to acclimate before contracting. The mutant allele used were rapx-2, rapx-3, w, rap3. In comparison to wild-type (CS), mutants ranged in severity with rapx-2 being the most impaired in locomotion (n= 100, p<0.0001 Student ‘t-test), followed by rapx-3 (n= 100, p<0.0001), and w, rap3 (n=100, p<0.0001, Figure 6C). These peristaltic waves are generated by central pattern (Choi et al., 2004). To test the speed of rap/fzr mutants we used the computer software, Worm tracker. The average speeds of each individual mutant larva were significantly decreased in rapX-3 (n= 87, p<0.0001) and w, rap3 (n= 91, p<0.0001) mutants when compared to wild type (Figure 6D) This data supports the changes seen in the other behavioral assays in that motility is greatly affected in rap/fzr loss-of-function mutants. This data are consistent with the role for APC/Crap/fzr/Cdh1 in synaptic development and function by further highlighting the significant system changes in the peripheral nervous system as seen by changes to locomotion and peristaltic movements.

DISCUSSION

Protein ubiquitination followed by degradation by the proteasomes as a key cellular regulatory mechanism is involved in a myriad of cellular processes. The subcellular localization of the ubiquitin ligases facilitates the precise spatial as well as temporal regulation of signaling mechanisms (Kim and Bonni 2012). The multi-subunit E3 Ubiquitin ligase APC/C is rapidly emerging as a critical regulator of neuronal morphogenesis and synaptic plasticity. The activating subunit Cdh1 appears to mediate the targeting of a wide variety of cellular substrates through its protein-protein interactions and thus affords diverse functional roles of the APC/C (Brandeis et al., 2002; Kaplow et al. 2007; Kaplow et al., 2008; Kim and Bonni, 2007). To uncover possible functional roles of Cdh1 at the synapse in the peripheral nervous system, we examined the phenotypes of the loss-of-function mutants of Drosophila-Rap/Fzr (Cdh1). We observed that loss-of-function rap/fzr mutants exhibit a number of morphological and functional changes at the larval NMJ synapse. One of the significant changes seen was in bouton morphology, in which misshapen boutons were decreased in number but increased in the area of boutons. The cellular basis for the abnormal morphology of the boutons is not entirely clear at this point. One possible explanation may be that the depleted vesicles following to the high frequency release may be trapped in the bouton membrane. Another possible explanation is that in Rap/Fzr mutants vesicle traffic and endocytosis is perturbed leading to abnormal morphology of the boutons. This is quite feasible as APC/C has been shown to regulate clathrin mediated endocytosis (Juo and Kaplan, 2004). To test whether the changes morphology was reflected in synaptic function we carried out electrophysiological studies. Although, we did not see any significant changes in evoked EJP, majority of neurons exhibited increased frequency of spontaneous miniature EJPs reflecting changes in the basal level of activity at the synapse. We also observed changes associated with fluorescent intensity with Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST that is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones. Bruchpilot is an important protein at the synapse, which functions in a similar manner to mammalian vesicle docking proteins (Wagh et. al 2006). Thus changes in Bruchpilot levels at the synapse can greatly influence the rate of synaptic transmission (Kittel et al., 2006; Fouget et al. 2009). Our data from the electrophysiological studies reported here is consistent with this idea. In addition, our data from transmission electron microscopy showed that the number of docked vesicles was decreased without any changes associated with the actual vesicle size. We propose that APC/C may regulate synaptic levels of Bruchpilot or proteins that interact with Bruchpilot by targeting them for ubiquitination (Zang et al. 2012). Further genetic interaction studies of rap/fzr with BRP mutants should allow us to test this hypothesis. For instance a single copy of a loss-of-function mutation in BRP would be expected to suppress the phenotype seen in rap/Fzr mutants.

Alterations in synaptic transmission data presented here reflect changes consistent with the immunohistochemical and TEM data that we have presented suggesting that Rap/Fzr may have role in stabilizing synaptic vesicle release. It is noteworthy that in our experiments reported here rap/fzr mutants showed an increase in glutamate receptors and decrease in bouton numbers. These results are similar to the results reported by van Roessel et al (2004) for the mutants in the ligase subunit of APC/C, the Apc2 (morula). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that APC/C-Cdh1/Rap/Fzr may play an essential role regulating the levels postsynaptic receptors. Although van Roessel et al (2004) did not report the localization of Cdh1 to postsynaptic regions; our results differ in this regard as we do detect weak Rap/Fzr in the localization in the postsynaptic regions (unpublished data not shown). Recent studies in other systems have also localized Cdh1 to postsynaptic regions (Reviewed in Yamada et al., 2012). The regulation of Glutamate receptors at the postsynapse may be a direct result of the role of Cdh1 in clathrin mediated endocytosis as has been reported in C.elegans (Burbea et al., 2002; Juo and Kaplan, 2004). Alternatively Rap/fzr may affect Glutamate localization through its interaction with other signal scaffolding proteins in the post synaptic regions. Our data presented here also show impaired larval locomotion in the rap/fzr mutants. We propose that the aberrant locomotion behavior reported here in rap/fzr mutants is a consequence of the structural and functional deficiencies at the synapse including the disorganization of the muscle structure. Taken together the data presented here argue for essential role for APC-Cdh1 in synaptic structure, function and muscle organization.

Highlights.

rap/fzr loss-of-function mutations led to changes in synaptic structure and function as well as locomotion defects.

rap/fzr loss-of-function mutants showed changes in size and morphology of synaptic boutons, and muscle tissue organization.

Electrophysiologically, mutants presented decreased transmission failure rates as well as increase in the size of synaptic potentials

In addition, larval locomotion and peristaltic movement were also impaired.

These findings suggest a novel role for Drosophila-Cdh1-mediated ubiquitinationduring development of functional synapses in the peripheral nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Confocal Microscopy Core Facilities of the City College of New York and the CCNY imaging center for preparation of TEM samples. The Microscopy Core of NYULMC, New York University, was used for TEM imaging. We are grateful to Dr. Wes Gruber of Columbia University for the use of the worm tracker. Research presented here was supported by grants from the NIH: 5G12RR003060-26 & 8G12MD7603 (TV) and R01GM088804 (A. U & C-F. W). A.W. was supported by NIH-RISE and LSAMP grants at the City College.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atwood HL, Govind CK, Wu CF. Differential ultrastructure of synaptic terminals on ventral longitudinal abdominal muscles in Drosophila larvae. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:1008–1024. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis AZ. Timing of APC/C substrate degradation is determined by fzy/fzr specificity of destruction boxes. EMBO Journal. 2002;21:4500–4510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbea M, Dreier L, Dittman JS, Grunwald ME, Kaplan JM. Ubiquitin and AP180 regulate the abundance of GLR-1 glutamate receptors at postsynaptic elements in C. elegans. Neuron. 2002;35:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubert EA, Condron BG. A behavioral stress assay in Drosophila larvae. CSH Protoc. 2007;2007 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4770. pdb prot4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. Ring domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieffers C, Peters BH, Kramer ER, Dotti CG, Peters JM. Expression of the CDH1-associated form of the anaphase-promoting complex in postmitotic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Sep 28;96(20):11317–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Ueda A, Wu CF. A modified minimal hemolymph-like solution, HL3.1, for physiological recordings at the neuromuscular junctions of normal and mutant Drosophila larvae. J Neurogenet 2004. 2004 Apr-Jun;18(2):377–402. doi: 10.1080/01677060490894522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergestad T, Broadie K. Interaction of stoned and synaptotagmin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1218–1227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01218.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet W, Owald D, Wichmann C, Mertel S, Depner H, Dyba M, Hallermann S, Kittel RJ, Eimer S, Sigrist SJ. Maturation of active zone assembly by Drosophila Bruchpilot. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:129–145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas KF, Broadie K. Roles of ubiquitination at the synapse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas KF, Miller SL, Friedman DB, Broadie K. The ubiquitin-proteasome system postsynaptically regulates glutamatergic synaptic function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang B, Chiba A. Single-cell analysis of Drosophila larval neuromuscular synapses. Dev Biol. 2001;229:55–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H, Richter D, Venkatesh T, Lehner C. Completion of mitosis requires neither fzr/rap nor fzr2, a male germline-specific Drosophila Cdh1 homolog. Curr Biol. 2002 Aug 20;12(16):1435–41. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juo P, Kaplan JM. The anaphase-promoting complex regulates the abundance of GLR-1 glutamate receptors in the ventral nerve cord of C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2057–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow ME, Korayem AH, Venkatesh TR. Regulation of glia number in Drosophila by Rap/Fzr, an activator of the anaphase-promoting complex, and Loco, an RGS protein. Genetics. 2008;178:2003–2016. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.086397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow ME, Mannava LJ, Pimentel AC, Fermin HA, Hyatt VJ, Lee JJ, Venkatesh TR. A genetic modifier screen identifies multiple genes that interact with Drosophila Rap/Fzr and suggests novel cellular roles. J Neurogenet. 2007;21:105–151. doi: 10.1080/01677060701503140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpilow J, Kolodkin A, Bork T, Venkatesh T. Neuronal development in the Drosophila compound eye: rap gene function is required in photoreceptor cell R8 for ommatidial pattern formation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1834–1844. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashevsky H, Wallace JA, Reed BH, Lai C, Hayashi-Hagihara A, Orr-Weaver TL. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome is required during development for modified cell cycles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172391099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AH, Puram SV, Bilimoria PM, Ikeuchi Y, Keough S, Wong M, Rowitch D, Bonni A. A centrosomal Cdc20-APC pathway controls dendrite morphogenesis in postmitotic neurons. Cell. 2009 Jan 23;136(2):322–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AH, Bonni A. Thinking within the D box: initial identification of Cdh1-APC substrates in the nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittel RJ, Wichmann C, Rasse TM, Fouquet W, Schmidt M, Schmid A, Wagh DA, Pawlu C, Kellner RR, Willig KI, Hell SW, Buchner E, Heckmann M, Sigrist SJ. Bruchpilot promotes active zone assembly, Ca2+ channel clustering, and vesicle release. Science. 2006;312:1051–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1126308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi Y, Stegmuller J, Matsuda T, Bonni S, Bonni A. Cdh1-APC controls axonal growth and patterning in the mammalian brain. Science. 2004;303:1026–1030. doi: 10.1126/science.1093712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwabe H, Brose N. The role of ubiquitylation in nerve cell development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:251–268. doi: 10.1038/nrn3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Shin YH, Hou L, Huang X, Wei Z, Klann E, Zhang P. The adaptor protein of the anaphase promoting complex Cdh1 is essential in maintaining replicative lifespan and in learning and memory. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1083–1089. doi: 10.1038/ncb1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listovsky T, Oren YS, Yudkovsky Y, Mahbubani HM, Weiss AM, Lebendiker M, Brandeis M. Mammalian Cdh1/Fzr mediates its own degradation. EMBO J. 2004;23:1619–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min VA, Condron BG. An assay of behavioral plasticity in Drosophila larvae. J Neurosci Methods. 2005 Jun 30;145(1–2):63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.11.022. Epub 2005 Jan 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM. The anaphase-promoting complex: proteolysis in mitosis and beyond. Mol Cell. 2002;9:931–943. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel AC, Venkatesh TR. rap gene encodes Fizzy-related protein (Fzr) and regulates cell proliferation and pattern formation in the developing Drosophila eye-antennal disc. Dev Biol. 2005;285:436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson IM, Ranjan R, Schwarz TL. Synaptotagmins I and IV promote transmitter release independently of Ca(2+) binding in the C(2)A domain. Nature. 2002 Jul 18;418(6895):336–40. doi: 10.1038/nature00915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell JD, Hicke L. Non-traditional functions of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35857–35860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist SJ, Lehner CF. Drosophila fizzy-related down-regulates mitotic cyclins and is required for cell proliferation arrest and entry into endocycles. Cell. 1997;90:671–681. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speese SD, Trotta N, Rodesch CK, Aravamudan B, Broadie K. The ubiquitin proteasome system acutely regulates presynaptic protein turnover and synaptic efficacy. Curr Biol. 2003;13:899–910. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmuller J, Bonni A. Moving past proliferation: new roles for Cdh1-APCin Postmitotic neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart BA, Atwood HL, Renger JJ, Wang J, Wu CF. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol A. 1994;175:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00215114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia N, Du J, Tyler WJ, Neale E, Pozzo-Miller L, Lu B. Protein synthesis-dependent and -independent regulation of hippocampal synapses by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37585–37593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roessel P, Elliott DA, Robinson IM, Prokop A, Brand AH. Independent regulation of synaptic size and activity by the anaphase-promoting complex. Cell. 2004;119:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Durrbeck H, Buchner S, Dabauvalle MC, Schmidt M, Qin G, Wichmann C, Kittel R, Sigrist SJ, Buchner E. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006;49:833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan HI, DiAntonio A, Fetter RD, Bergstrom K, Strauss R, Goodman CS. Highwire regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 2000;26:313–329. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Yang Y, Bonni A. Spatial organization of Ubiquitin ligase pathways orchestrates neuronal connectivity. Trens Neurosci. 2012;36(4):218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang S, Ali YO, Ruan K, Zhai RG. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase maintains active zone structure by stabilizing Bruchpilot. EMBO Rep 2013. 2013 Jan;14(1):87–94. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wu CF. Alteration of four identified K+ currents in Drosophila muscle by mutations in eag. Science. 1991;252:1562–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.2047864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wu CF. Modulation of different K+ currents in Drosophila: a hypothetical role for the Eag subunit in multimeric K+ channels. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4669–4679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-11-04669.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]