Abstract

Fragile X-associated Tremor Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS) results from a CGG repeat expansion in the 5’UTR of FMR1. This repeat is thought to elicit toxicity as RNA yet disease brains contain ubiquitin-positive neuronal inclusions, a pathologic hallmark of protein-mediated neurodegeneration. We explain this paradox by demonstrating that CGG repeats trigger repeat associated non-AUG initiated (RAN) translation of a cryptic polyglycine-containing protein, FMRpolyG. FMRpolyG accumulates in ubiquitin-positive inclusions in Drosophila, cell culture, mouse disease models and FXTAS patient brains. CGG RAN translation occurs in at least two of three possible reading frames at repeat sizes ranging from normal (25) to pathogenic (90), but inclusion formation only occurs with expanded repeats. In Drosophila, CGG repeat toxicity is suppressed by eliminating RAN translation and enhanced by increased polyglycine protein production. These studies expand the growing list of nucleotide repeat disorders where RAN translation occurs and provide evidence that RAN translation contributes to neurodegeneration.

A diverse group of human neurological disorders result from nucleotide repeat expansions (Orr and Zoghbi, 2007). These mutations can cause disease by protein gain-of-function, protein loss-of-function, or RNA gain-of-function mechanisms. For dominantly inherited repeat expansion disorders, defining whether the gain-of-function toxicity is elicited as RNA or as protein has traditionally depended on whether the repeat resides in an open reading frame (ORF) within an exon. For example, in Huntington’s disease and other polyglutamine neurodegenerative disorders, expansion of exonic CAG repeats encoding polyglutamine promotes aggregation and alterations in the native properties of disease proteins (Orr and Zoghbi, 2007). In contrast, in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 a CUG repeat expansion in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the DMPK gene causes toxicity predominantly as RNA (Cooper et al., 2009). The CUG repeat forms a hairpin structure that binds and sequesters certain splicing factors while also triggering activation of other pathogenic cascades.

Recently, however, the line separating RNA and protein gain-of-function nucleotide repeat diseases has begun to blur. RNA-mediated toxicity has now been proposed to contribute to polyglutamine diseases (Li et al., 2008) and bi-directional transcription through expansions can lead to repeats in both “coding” and “non-coding” mRNAs, raising the possibility that multiple toxic species may be produced from a single expansion (Ladd et al., 2007; Moseley et al., 2006; Wilburn et al., 2011). Moreover, evidence now suggests that repeats can be translated into proteins even if they do not reside in an AUG-initiated open reading frame (Zu et al., 2010). This Repeat Associated Non-AUG initiated (RAN) translation can occur in all three possible ORFs of a given transcript, leading to numerous potentially toxic entities from a given repeat sequence (Pearson, 2011). RAN translation was recently shown to occur through the C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat expansion that causes ALS and frontotemporal dementia (Ash et al., 2013; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Mori et al., 2013; Renton et al., 2011). These new findings raise key questions about how RAN translation occurs and whether it contributes directly to neurodegeneration. As the expected mechanisms of toxicity differ depending on whether the inciting agent is RNA or protein, defining the critical toxic species in each repeat expansion disorder is an important step toward therapeutic development.

To explore the respective roles of RNA and RAN translation in repeat associated neurodegeneration, we investigated Fragile X-associated Tremor Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS), a common inherited cause of gait disorder, dementia and tremor (Jacquemont et al., 2004). FXTAS is caused by a modestly expanded CGG nucleotide repeat (55–200) in the 5’ untranslated region of the fragile X mental retardation gene, FMR1. Much larger expansions of the same repeat cause fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited form of mental retardation, by silencing FMR1 transcription (Penagarikano et al., 2007). By contrast, in FXTAS patients and animal models the moderately expanded CGG repeat is associated with elevated FMR1 mRNA expression, neurodegeneration, and intranuclear neuronal inclusions that contain the CGG repeat mRNA and various proteins (Greco et al., 2006; Tassone et al., 2004). Research to date has focused on how the repeat might trigger neurodegeneration through an RNA mechanism (Jin et al., 2007; Sellier et al., 2010; Sofola et al., 2007), but critical aspects of disease pathology are not explained by a purely RNA-mediated process. Notably, the inclusions in FXTAS brains differ from seen in other RNA-mediated disorders: they are large, ubiquitinated aggregates containing chaperone proteins such as HSP70 and many other proteins that do not interact directly with CGG repeat mRNA (Greco et al., 2006; Iwahashi et al., 2006). The inclusions of FXTAS instead more closely resemble neuronal intranuclear inclusions seen in polyglutamine diseases and other protein-mediated neurodegenerative disorders (Williams and Paulson, 2008).

Here we explain this paradox. We demonstrate that the CGG repeat expansion in FXTAS triggers RAN translational initiation within the 5’UTR of FMR1 mRNA through an AUG independent mechanism. The translated product, a cryptic polyglycine-containing protein we name FMRpolyG, is toxic in Drosophila and in human cell lines, capable of driving intranuclear inclusion formation, and present in FXTAS patient brains. The ability to produce FMRpolyG also explains pathologic discrepancies between two mouse models of FXTAS and directly influences the toxicity of CGG repeat constructs in Drosophila. Our findings support a disease model in which RAN translation of an expanded polyglycine protein contributes to FXTAS disease pathogenesis and suggest novel approaches toward therapeutic development in this and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Results

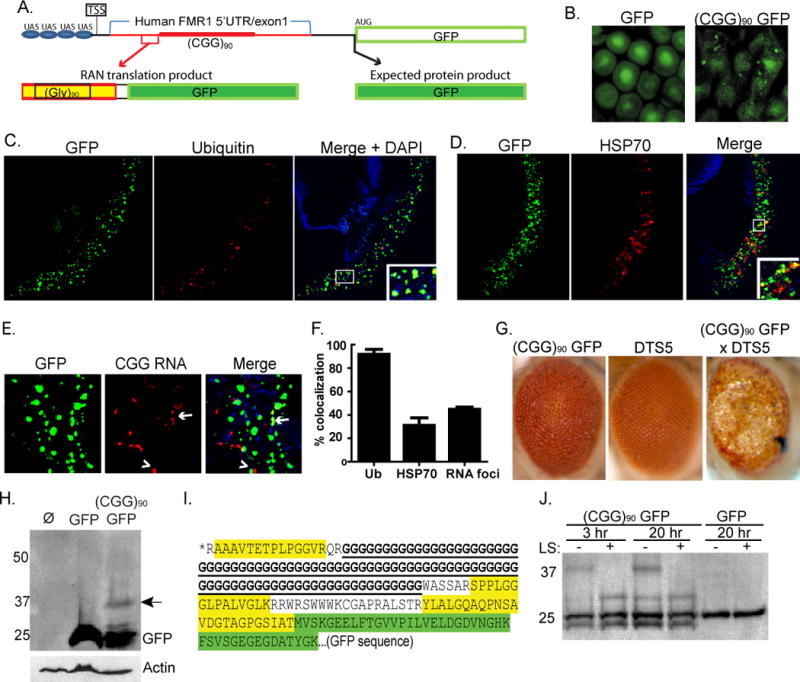

Repeat associated non-AUG initiated translation and inclusion formation in a Drosophila model of FXTAS

To explore the mechanism of inclusion formation in FXTAS, we utilized a Drosophila model of CGG repeat mediated neurodegeneration in which the 5’UTR from a FXTAS patient containing 90 CGG repeats is placed upstream of the coding region for GFP (Fig. 1A, (Jin et al., 2003; Todd et al., 2010)). Initially designed to evaluate RNA-mediated toxicity, the (CGG)90 GFP expressing flies exhibit repeat length-dependent retinal degeneration (Jin et al., 2003). Remarkably, GFP-positive inclusions accumulate in (CGG)90 GFP expressing flies but not in flies expressing GFP alone (Fig. 1B). These inclusions form in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, and immunostain positively for ubiquitin and the chaperone HSP70 (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1. CGG RAN translation in a Drosophila model of FXTAS.

A) Schematic of (CGG)90 GFP fly construct. A novel polyglycine protein is produced in these flies by RAN translation proceeding through the CGG repeat. Black sequence is vector derived and red sequence is human derived. Thicker red line is CGG repeat. The black arrow shows the expected AUG translational initiation site for GFP and the expected product. The red bracket and arrow show the RAN translational initiation region for the polyglycine-GFP fusion protein identified by tandem-MS. TSS is the presumed transcription start site. B) GFP inclusions in oomatidia from (CGG)90 GFP, but not GFP, expressing flies. C) Confocal micrographs of transverse retinal sections from gmr-GAL4; (CGG)90 GFP flies reveal nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions that co-localize with ubiquitin. D) (CGG)90 GFP inclusions partially co-localize with HSP70. E) In situ hybridization using a Cy5(CCG)6 RNA probe on transverse retinal sections. CGG RNA foci form in the nucleus and cytoplasm of (CGG)90 GFP flies and are either distinct from (arrowhead), or overlap with(arrow), GFP inclusions. F) Quantitation of co-localization of GFP aggregates with ubiquitin, HSP70, and CGG RNA foci. G) Co-expression of proteasomal subunit mutant DTS5 with (CGG)90 GFP enhances retinal degeneration at 28C. H) A HMW band is seen with anti-GFP antibody (arrow) in lysates from (CGG)90-GFP expressing flies. Lane 1, gmr-GAL4 flies (negative control); lane 2, gmr-GAL4; uas GFP; lane 3, gmr-GAL4; uas (CGG)90 GFP. I) tandem-MS analysis of the HMW GFP band identifies three peptides (yellow) indicating that translation initiates above the repeat. Green sequence is GFP. *Predicted peptides above the indicated AA sequence were not detected. J) The HMW GFP product is selectively digested by the polyglycine endopeptidase, lysostaphin (LS). Unless stated, error bars represent SEM in all graphs.

CGG repeat RNA forms foci in FXTAS patients and in cell models of disease (Sellier et al., 2010; Tassone et al., 2004). We therefore evaluated whether the observed GFP inclusions in (CGG)90 GFP expressing flies co-localize with RNA foci. Multiple nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA foci were observed in retinal sections probed with a Cy5-(CCG)6 RNA probe (Fig. 1E, S1A) (Sellier et al., 2010). Only a fraction (43%) of RNA foci co-localized with GFP-positive inclusions (Fig. 1F).

In principle, the GFP inclusions could result from general impairment of the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) by CGG repeat-containing mRNA/protein complexes. Arguing against this possibility, however, is the fact that co-expression of the temperature-sensitive â2 proteasomal subunit mutant DTS7 with GFP did not result in GFP inclusions (Fig. S1B and data not shown), whereas it did induce inclusion formation by a more aggregate-prone fluorescent reporter, DsRed (Fig. S1C). We next crossed flies expressing (CGG)90 GFP with flies expressing DsRed. In this cross, if GFP inclusions resulted from a general toxic effect of the repeat then the aggregation-prone DsRed should also form inclusions that co-aggregate with GFP. These flies, however, developed GFP-positive inclusions without co-aggregation of DsRed, suggesting that inclusion formation requires the CGG repeat to be present in the same mRNA that encodes GFP (Fig. S1D). The presence of GFP inclusions prompted us to test whether enhancing or suppressing protein quality control pathways could modulate retinal degeneration in (CGG)90 GFP expressing flies. Consistent with a protein-mediated effect, retinal degeneration was enhanced by co-expressing the temperature-sensitive proteasomal subunit mutation, DTS5 (â6 subunit) and suppressed by co-expression of the chaperone protein HSP-70 (Fig. 1G, (Jin et al., 2003) and data not shown).

A recent report suggests that CAG repeats can trigger unconventional translation initiation (RAN translation) in the absence of an AUG start codon (Zu et al., 2010). We therefore asked whether CGG repeats trigger RAN translation upstream of, and in frame with, the GFP coding sequence to generate a higher molecular weight (HMW) GFP fusion protein that is prone to aggregate. Indeed, western blot analysis of (CGG)90 GFP Drosophila lysates revealed an additional GFP species ~12 kD larger than GFP(Fig. 1H, arrow). Sequence analysis ruled out an unexpected upstream ATG, mutation in the GFP coding sequence or loss of the GFP stop codon as the basis for this HMW GFP (Full sequence is in Fig. S1E). Stringent immunoprecipitations from (CGG)90 GFP lysates (Fig. S1F) also excluded ubiquitination as the cause of the HMW GFP protein.

Tandem mass spectroscopy of GFP immunoprecipitates from (CGG)90GFP Drosophila lysates confirmed the presence of an unconventional translation product. Three novel peptides were identified that correspond to the predicted protein sequence downstream of the repeat if the FMR1 5’UTR were translated (Fig. 1I). These peptides were not detected in flies expressing GFP alone and are not predicted to exist in the Drosophila proteome. Based on the apparent molecular weight of the observed product, the identified peptide sequences corresponding to the 5’ UTR, and the reading frame of GFP, we conclude that the repeat is translated in the GGC reading frame to produce a 90 amino acid polyglycine stretch at the N-terminus of the protein, with translation initiating just 5’ to the repeat. Consistent with this, further analysis identified a fourth peptide immediately N-terminal to the polyglycine repeat (Fig. 1I) but no other peptides above this region.

No polyglycine fragment was detected by tandem MS, reflecting the lack of trypsin cleavage sites in expanded polyglycine. To confirm that the novel translation product contains polyglycine, we treated immunoprecipitates with lysostaphin, a specific pentaglycine endopeptidase (Huber and Schuhardt, 1970). Lysostaphin successfully cleaved the HMW GFP species from (CGG)90 GFP lysates but had no effect on GFP alone, confirming the presence of a polyglycine repeat (Fig. 1J).

RAN translation produces a polyglycine-containing protein in mammalian cells

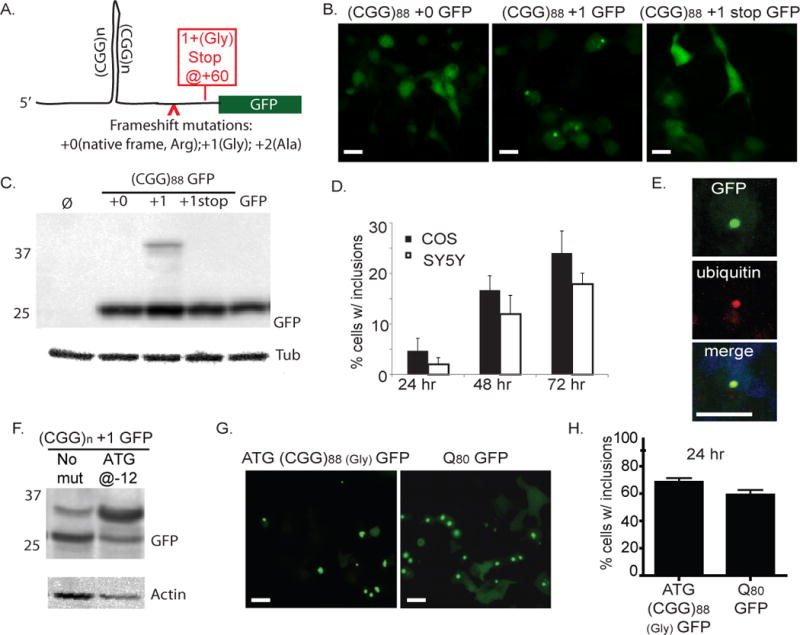

Zu et al recently described Repeat Associated Non-AUG initiated (RAN) translation triggered by CAG/CUG repeat expansions (Zu et al., 2010) in which translation initiates in all three possible reading frames, beginning within the hairpin itself. To test whether a similar phenomenon occurs with CGG repeat expansions, we transfected COS cells or SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with a construct containing the FMR1 5’UTR from a FXTAS patient with 88 CGG repeats placed upstream of GFP (Fig. 2A, Table S1). Importantly, this construct differs from the (CGG)90 GFP fly sequence in that the GFP start codon resides in the CGG arginine-encoding frame relative to the repeat (specified as +0 in all figures). This frame recapitulates the relationship of the repeat to the FMRP ORF in FMR1 mRNA. In contrast, the GFP start codon in the Drosophila model resides in the GGC glycine-encoding frame (specified as +1 in all figures). For consistency, the repeat is referred to as CGG in all figures regardless of the frame in which it is translated, with modifiers placed before or after the repeat to indicate the relevant ORF and protein product and any introduced sequence changes. The sequences of all constructs are included in Table S1.

Figure 2. CGG repeats trigger RAN translation and inclusion formation in mammalian cells.

A) Schematic of (CGG)88-GFP vector and mutations introduced in various constructs. Arrowhead shows the site of additional base insertions to shift the frame of GFP relative to the repeat. Red box reflects stop codon introduced in the +1 (Gly) frame. Full sequences of all constructs are shown in Table S1B) In COS cells 72 hours after transfection with (CGG)88-GFP constructs, inclusions were observed when the CGG repeat was located in the +1 (Gly) frame, but not in native CGG +0 (Arg) frame. Far right panel includes a stop codon inserted between the repeat and the GFP coding sequence. C) COS cell lysates 72 hr after transfection with indicated plasmids, probed on western blot with antibodies to GFP or Tubulin. D) Quantification of inclusion formation by (CGG)88 +1GFP in COS or SY5Y neuroblastoma cells 24, 48, and 72 hrs after transfection. E) Confocal microscopy showing inclusion in a SY5Y cell expressing (CGG)88 +1GFP, stained for ubiquitin (red) and co-stained for DAPI (blue). F) An ATG start site placed upstream of the repeat in the +1 (Gly) frame (ATG-(CGG)88 +1GFP) increases translation of the HMW GFP product. G) ATG-(CGG)88 GFP) enhances GFP inclusion formation similar to levels seen with a polyglutamine peptide fused to GFP (Q80-GFP), an aggregation-prone positive control. H) Comparison of % GFP positive cells with inclusions upon expression of ATG-(CGG)88 GFP or Q80-GFP 24 hours after transfection.

Expression of the (CGG)88 +0 GFP construct led to diffuse GFP expression in transfected cells (Fig. 2B) as previously reported (Arocena et al., 2005). To test whether RAN translation might initiate in other reading frames through the repeat, we added one or two bases between the CGG repeat and the ATG start codon of GFP: +1 (GGC, glycine-encoding) and +2 (GCG, alanine-encoding). As in (CGG)90 GFP flies, the +1(Gly) frame induced GFP inclusions in COS and SY5Y cells that accumulated over time (Fig. 2B, D) and were predominantly intranuclear and ubiquitin-positive (Fig. 2E). Predictably, placing a stop codon after the repeat but before the GFP start site blocked GFP inclusion formation in the +1(Gly) frame (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the lack of a HMW FMRP species in FXTAS patients and animal models, no GFP-positive inclusions were identified in the +0 frame, despite the absence of intervening stop codons between the repeat and the ATG initiation codon of GFP. To test for the appearance of similar RAN translation products in mammalian cells as observed in Drosophila, we performed western blots on cell lysates 72 hours after transfection with each construct. A HMW GFP species was produced only in the +1 (Gly) frame and was no longer produced when a stop codon was placed between the repeat and the GFP start codon (Fig. 2C). With the (CGG)88 +1 GFP construct, this HMW GFP species constituted ~10% of the total cellular pool of GFP.

In a parallel set of experiments, we generated constructs in which GFP lacked its canonical start codon. As expected, this mutation markedly reduced the production of GFP in transfected cells, but when a 55 CGG repeat sequence was inserted upstream of this ATG-less GFP, placing the repeat in the glycine (+1)-encoding frame relative to GFP, the number of GFP-positive cells recovers to 60% of that seen with ATG-GFP (Fig. S2A, B). In contrast, placing the CGG repeat in the Arginine (+0)-encoding frame did not significantly increase the number of GFP-positive cells (Fig. S2A, B). These findings correlated with production of RAN translation products as assessed by western blot: the HMW-GFP protein level was ~10% of that produced from GFP alone, while translation products from the +0 (Arg) construct were below the limit of detection (Fig. S2C).

Studies comparing the aggregation properties of homopolymeric peptides suggest that small stretches of polyglycine are not prone to aggregation (Oma et al., 2004). To evaluate the aggregation properties of an expanded polyglycine-containing protein in FXTAS, we introduced an ATG start site upstream of the repeat in the glycine frame fused to GFP (ATG- (CGG)88 +1 GFP). Incorporation of a canonical start site markedly increased production of the HMW GFP (Fig. 2F), leading to inclusion formation in most cells 24 hours after transfection, which is comparable to the rate of inclusion formation seen when expanded polyglutamine is fused to GFP (Q80 GFP, Fig. 2G, H).

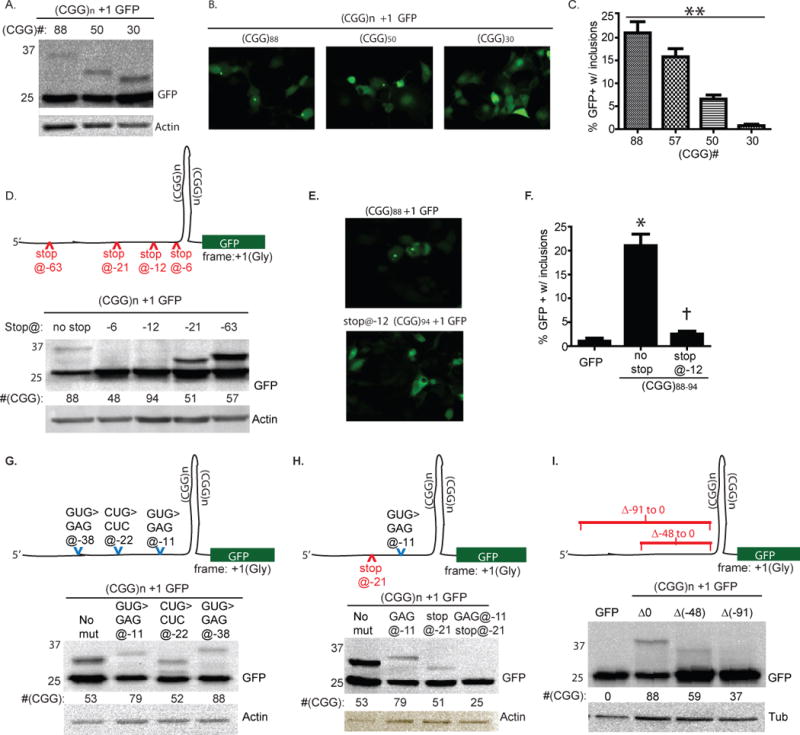

Because the risk of developing FXTAS increases with larger repeats (Leehey et al., 2008), we evaluated the impact of repeat length on the production and aggregation of HMW GFP. The normal FMR1 repeat in humans is between 20 and 45 CGGs, usually interrupted by one or two intervening AGGs. Constructs with 30, 50, or 88 CGG repeats in the +1 (Gly) frame with GFP all resulted in HMW GFP production (Fig. 3A). Remarkably, production of the RAN translation product appeared to increase with decreasing repeat size, which may reflect differences in the transfer efficiency to PVDF membrane or greater translational efficiency for GFP and HMW GFP with shorter repeats (Chen et al., 2003). In contrast, aggregation decreased with decreasing repeat size, such that inclusions were infrequent at 50 repeats and nearly absent at 30 CGG repeats, suggesting a repeat-length dependence to aggregation (Fig. 3B, C). This repeat-length dependence to inclusion formation was consistent across numerous cell types including primary cortical neurons (Fig. S2D). Consistent with published studies, longer repeats were also associated with decreased cellular viability (Fig. S2E, (Arocena et al., 2005; Handa et al., 2005; Sellier et al., 2010).

Figure 3. CGG RAN translation in glycine reading frame occurs at normal repeat lengths, initiates before the repeat, and does not require a specific non-AUG codon.

A) RAN translation occurs even with shorter repeats in the +1 (Gly) frame. B) Representative fluorescent micrographs of cells transfected with (CGG)n +1 GFP constructs with the indicated number of repeats. C) Percent transfected COS cells with GFP+ inclusions 72 hours after transfection of (CGG)n +1 GFP of the indicated repeat lengths. D) (Top) Schematic of (CGG)n +1 GFP construct with location of introduced stop codon mutations. (Bottom) Western blot of cell lysates 72 hrs after transfection with the indicated constructs. Placing a stop codon 6 or 12 bp 5’ to the repeat inhibits production of HMW GFP. E) Fluorescent micrographs of COS cells expressing (CGG)88 +1 GFP or stop@-12 (CGG)94 +1 GFP, 72 hrs after transfection. F) Quantitation of GFP inclusion formation in the presence or absence of a stop codon −12 bp 5’ to the CGG repeat. G) (Top) Schematic demonstrating position of specific mutations in “near AUG” codons that might serve as alternative start sites for CGG RAN translation in the +1 glycine frame. (Below) Western blot of lysates from cells expressing the indicated constructs demonstrates that eliminating any single near AUG codon is insufficient to block RAN translation. H) (Top) Schematic demonstrating position of stop codon and near AUG codon mutation introduced into (CGG)n +1 GFP construct. (Below) The elimination of a near AUG codon at −11 (lane 2) or the presence of a stop codon at −21 (lane 3) allows HMW GFP translation, but combining these mutations (lane 4) eliminates HMW GFP production. I) (Top) Schematic demonstrating deletion mutations that remove 48 or 91 nt just 5’ proximal to the repeat. (Below) Western blot demonstrating that removal of proximal sequence partially or completely impedes RAN translation in the +1 (Gly) frame. For this and other figures, differing sizes of the HMW GFP-positive bands reflect repeat instability incurred during cloning; repeat size is shown below the GFP blot for each lane. Positions of specific mutations are defined relative to the 5’ start of the repeat. Full sequences of all constructs are in Table S1. **P < 0.001 for trend, one way ANOVA, *p < 0.001 versus GFP, †p < 0.001 vs. (CGG)88 +1GFP, t-Test.

RAN translation of polyglycine protein initiates 5’ to the CGG repeat

To elucidate the mechanism by which RAN translation initiation occurs, we created a series of mutations in the sequence 5’ to the repeat to determine the minimal requirements for initiation. We first introduced a stop codon at −6bp, −12bp, −21bp or −63bp from the start of the CGG repeat (Fig. 3D). Stop codons placed at −6bp or −12bp prevented the appearance of GFP-positive inclusions and HMW GFP (Fig. 3D–F). In contrast, placement of a stop codon at −21 or −63bp did not block production of HMW GFP, suggesting that RAN translation initiates between 21 and 12 bases 5’ of the CGG repeat (Fig. 3D).

The bias towards translation in the glycine reading frame suggested preferred initiation at a specific non-AUG start site. A plausible explanation is the use of a specific alternative start codon as the translational origin rather than initiation within the hairpin itself. However, serially mutating each potential alternative start codon (i.e. “near-ATG” codons, differing by a single base from AUG) in the glycine frame within 60bp 5’ of the CGG repeat did not eliminate production of HMW GFP (Fig. 3G and data not shown). This result suggests either that a near-AUG codon is not needed to initiate translation or that multiple, different near-AUG codons proximal to the repeat can be utilized, so that eliminating any one near-AUG codon is not sufficient to prevent translation. To address this latter possibility, we placed a stop codon at − 21bp, which by itself does not prevent production of HMW GFP (Fig. 3H), and mutated the only potential near-ATG codon downstream of this stop codon, a GUG codon at −11bp. Mutating this GUG codon to GAG by itself had no impact on HMW GFP production, but combined with the stop codon at −21, HMW GFP production was lost (Fig. 3H). This result suggests that, at least for some sequence contexts, a near-AUG codon close to the repeat is required for CGG RAN translation initiation but the specific sequence 5’ to the repeat is less critical. To evaluate this, we deleted 48nt just 5’ proximal to the CGG repeat which impaired production of HMW GFP (Fig. 3I). Deleting 91nt 5’ proximal to the repeat nearly eliminated HMW GFP production, which could reflect the importance of the specific sequence just proximal to the repeat or represent a consequence of shortening the distance between the transcription start site and the repeat (Fig. 3I).

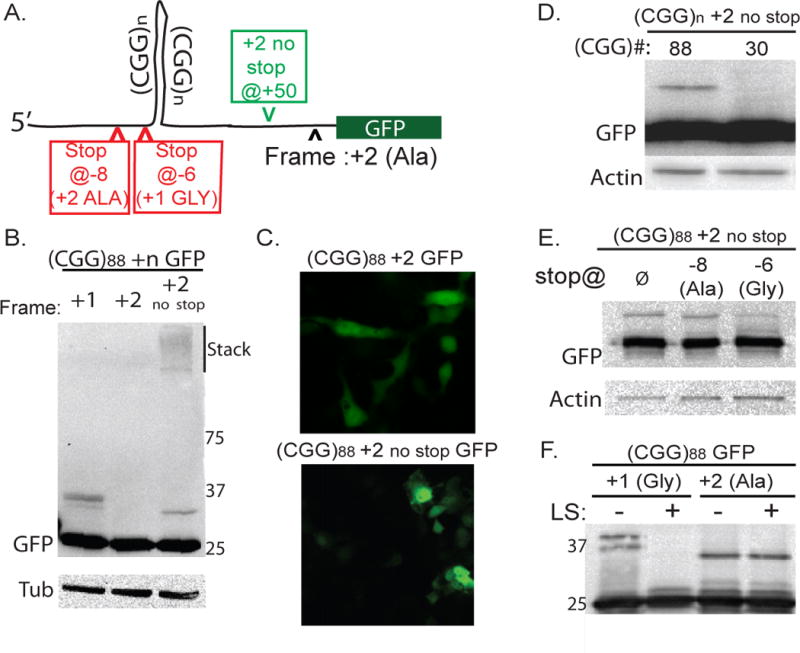

RAN translation also occurs in the alanine reading frame

RAN translation associated with CGG repeats was not restricted to the glycine frame. In the +2 (GCG, alanine-encoding) frame, removing an in-frame stop codon between the repeat and the GFP coding sequence led to a HMW GFP band and aggregated protein (Fig. 4A, B) although GFP-positive inclusions were not seen in transfected cells (Fig. 4C). The +2 (Ala) frame HMW GFP species electrophoreses as a slightly smaller protein than what is seen with identical sized repeats in +1 (Gly) frame constructs, suggesting a different site of initiation (Fig. 4B). In contrast to our results in the +1 (Gly) frame, reducing the repeat size to 30 CGGs eliminated expression of HMW GFP in the +2 (Ala) frame (Fig. 4D). When a stop codon was introduced in the +2 (Ala) frame at −8bp from an expanded (CGG)88 repeat, expression of the HMW GFP persisted (Fig. 4E). This result could reflect translational initiation in the +1 (Gly) frame followed by a frameshift into the +2 (Ala) frame, as frameshifts are known to occur with longer CAG repeat expansions (Stochmanski et al., 2012). To test this possibility, we introduced an upstream stop codon (−6bp) in the +1 (Gly) frame while placing the downstream GFP sequence in the +2 (Ala) frame. This did not eliminate expression of a HMW GFP product (Fig. 4E). To further exclude a Gly to Ala frame shift, we incubated lysates from cells expressing (CGG)88 +1 GFP or (CGG)88 +2 GFP with lysostaphin. Lysostaphin degraded HMW GFP produced in the +1 (Gly) frame but not in the +2 (Ala) frame (Fig. 4F). We conclude that RAN translation associated with CGG repeats in the FMR1 5’TR occurs in at least two of three possible reading frames, but the constraints on translational initiation appear to differ for these two frames.

Figure 4. A RAN translation product is also produced in the alanine (GCG) frame.

A) Schematic of (CGG)88 +2 GFP construct. Green arrowhead indicates where an intervening stop codon was removed. Red arrowheads indicate introduced stop codons. B) Unconventional translation resulting in a discrete HMW-GFP species and aggregated protein in the stack is detected in the +2 (GCG, alanine-encoding) frame when an intervening stop codon is removed. C) No GFP inclusions are observed in +2 (Ala) constructs even when the intervening stop codon is removed. D) HMW polyalanine product is absent with shorter CGG repeats. E) In +2 frame constructs, introduction of a stop codon at −8bp (in the +2 frame) does not eliminate the RAN translation product. A stop codon at −6bp (in the +1 frame) reduces but does not eliminate HMW GFP. F) 3 hr digestion of GFP immunoprecipitates with Lysostaphin eliminates the HMW species in the +1 (Gly) frame but not in the +2 (Ala) frame.

The FMR1 5’TR is engaged with translating ribosomes

CGG RAN translation in Drosophila and transfected mammalian cells suggests that unconventional translation may also occur in FXTAS patients. To explore this possibility, we first assessed whether the 5’TR of FMR1 mRNA is associated with translating ribosomes by querying ribosome profiling datasets previously generated in human cell lines (Guo et al., 2010; Hsieh et al., 2012; Ingolia et al., 2012). This technique combines ribosomal foot printing with next generation sequencing to identify sites of active translation. In examining the distribution of ribosomes on FMR1mRNA in published datasets, we observed that most sequence reads occurred, as expected, over coding regions of the FMR1mature mRNA sequence (Fig. 5A) with few if any reads in introns or the 3’TR. However, in the 5’TR of FMR1 mRNA, two peaks of protected sequence were present in the region just 5’to the CGG repeat (Fig. 5A), suggesting that fully assembled translating ribosomes do reside in this region of FMR1 RNA in human cells. These peaks exhibited ~40% of the mean read coverage and 60% of the peak read coverage observed in the first coding exon of FMR1 and were consistent across 3 published datasets in different human cell lines (Hsieh et al., 2012; Ingolia et al., 2012). Analysis of 3 mouse cell line datasets revealed a similar set of peaks just 5’ to the CGG repeat (Figure S4C, D) (Guo et al., 2010; Ingolia et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Thoreen et al., 2012).

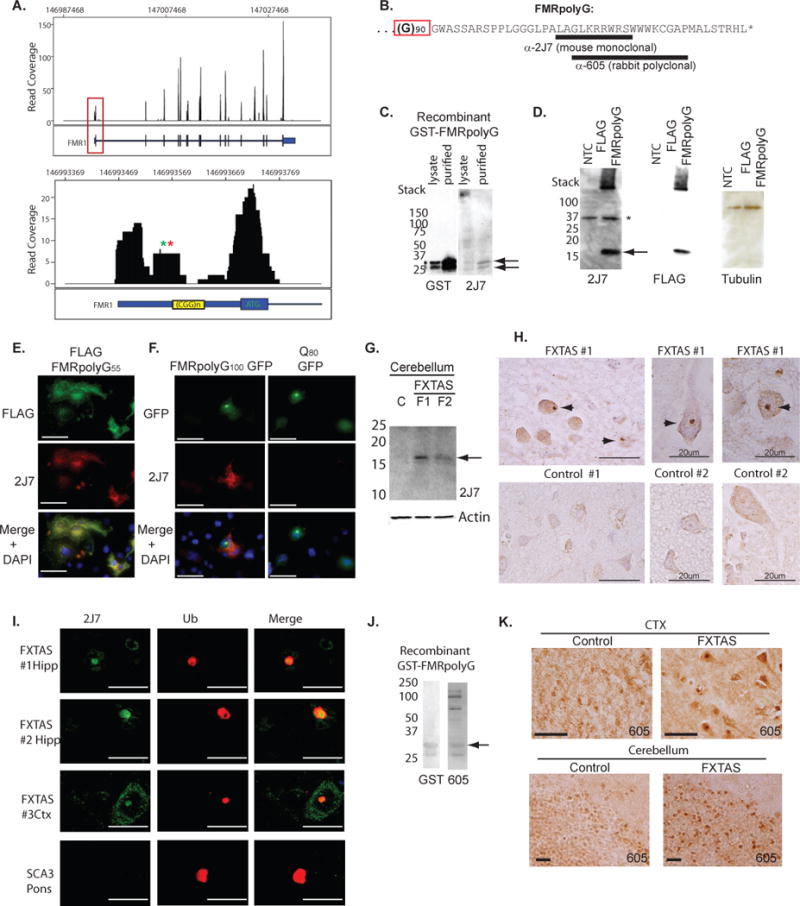

Figure 5. The predicted polyglycine protein is present in FXTAS patient brains.

A) Read coverage map of FMR1 locus derived from a published ribosomal profiling dataset in HEK-293 cells (Ingolia et al., 2012). Numbers along the X axis represent position within the genome. Y axis represents number of sequence reads at each position. Black bars represent exons, intervening sequences are introns, and blue boxed sequences represent 5’UTR (left) and 3’UTR (right). Red box indicates the region shown at higher resolution in the lower panel, which includes the FMR1 5’UTR and first exon. Green and red asterisks indicate position of possible near AUG initiation codons iGUG (12bp proximal to repeat) and iCTG (24bp proximal to repeat), respectively. Note significant reads over region 5’ proximal to the CGG repeat sequence. B) Predicted sequence of human FMRpolyG protein with 90 glycines. Underlined regions represent peptides used to generate 2J7 and 605 antibodies. Polyglycine sequence is indicated by red box. C) GST and 2J7 antibody staining of recombinant purified GST-HIS-FMRpolyG30 protein. D) Expression of an FLAG (CGG)55 FMRpolyG construct in COS cells stained with 2J7 and re-probed with anti-FLAG antibody and Tubulin. The protein runs higher than expected based on predicted size. NTC = no template control. E) Immunofluorescence with FLAG (green) and 2J7 (red) in COS cells expressing FLAG-FMRpolyG55. F) Co-immunofluorescence of GFP and 2J7 signal in COS cells expressing FMRpolyG100 GFP (left panels) or Q80 GFP (right panels). G) Western blot with 2J7 of cerebellar lysates from 2 FXTAS patients and an age-matched control. Arrow indicates bands seen in FXTAS but not control samples. H) Representative images of 2J7 immunostaining from frontal cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (Hipp) of control and FXTAS brain. I) Co-immunofluorescence with 2J7 (green) and anti-ubiquitin (red) in FXTAS hippocampus (top two panels) or cortex (3rd panel) from three different FXTAS subjects. In contrast, ubiquitinated inclusions in the pons of a patient with the polyglutamine disorder SCA-3 do not co-stain with 2J7. J) GST and rabbit polyclonal Ab605 staining of recombinant FMRpolyG protein. Arrow indicates band recognized by GST and Ab605. K) Representative images of Ab605 immunostaining of frontal cortex (CTX) and cerebellum from control and FXTAS brain. Unless otherwise noted, scale bars represent 50 microns.

Data from studies utilizing the translational inhibitor Herringtonine to stall ribosomes at initiation suggest that many transcripts contain active uORFs with initiation at alternative translational initiation sites (aTIS) (Fig S4) (Fritsch et al., 2012; Ingolia et al., 2011). Consistent with this observation, the average read density over the FMR1 5’UTR was comparable to the majority of transcripts across datasets in both human and mouse samples. We therefore focused our attention on the enhanced read density over near-AUG codons just 5’ proximal to the repeat, given that our cell culture data was most consistent with initiation in this region. We reasoned that enhanced read density could represent pausing of assembling ribosomes at initiation sites (Ingolia et al., 2011). The read density over two specific near-AUG codons (iGTG -12nt 5’ to the repeat and iCTG -24nt 5’ to the repeat) was significantly enhanced compared to other nucleotide triplets within the FMR1 5’ UTR (Fig S4A, B). Similarly, the mouse fmr1 5’UTR also exhibited peaks of increased RP read density just 5’ proximal to the repeat that correlated with Herringtonine identified initiation sites at near-AUG codons (Fig S C, D). When compared to the distribution of read densities within 5’UTRs on a transcriptome-wide level, these sites within the FMR1/fmr1 5’UTR demonstrate relative read densities that are comparable to Herringtonine confirmed alternative translational initiation sites (Fig S4E–G). Taken together, these data are consistent with translational initiation within the 5’ UTR of FMR1/fmr1 just proximal to the CGG repeat.

The FMR1 polyglycine protein is present in FXTAS patient brains

Translation of a 90 CGG repeat-containing FMR1 mRNA is predicted to produce an 11.5 kD protein that contains an N-terminal polyglycine stretch followed by a 42 amino acid carboxyl terminal domain out of frame with the downstream FMRP start codon; we named this predicted protein FMRpolyG (Fig. 5B). To determine whether FMRpolyG is made in FXTAS patients, we developed a monoclonal antibody (2J7) against a peptide from the predicted human protein (Fig. 5B). Tested against recombinant FMRpolyG generated in bacteria as a GST-HIS fusion, 2J7 recognized two bands in bacterial lysates and purified protein samples (Fig. 5C) that were confirmed by tandem MS to be FMRpolyG. In transfected mammalian cells expressing a FLAG-tagged FMRpolyG with 55 repeats, both 2J7 and FLAG antibody detected a protein electrophoresing at a slightly higher than expected MW of ~16kD (Fig. 5D). In transfected COS cells, FLAG-FMRpolyG55 displayed diffuse nucleocytoplasmic staining with occasional intranuclear inclusions detected by immunofluorescence with either 2J7 or anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 5E). 2J7 immunostaining also co-localized with GFP inclusions formed in cells expressing FMRpolyG100-GFP (Fig. 5F). In contrast and as expected, 2J7 staining did not co-localize with GFP or inclusions in cells expressing an expanded polyglutamine-GFP fusion (Fig. 5F).

To evaluate whether FMRpolyG is expressed in FXTAS patient brains, we performed western blots on cerebellar lysates from FXTAS patients. In pathologically confirmed FXTAS cases, a ~15kD band was identified in FXTAS lysates but not in control or AD brain lysates (Fig. 5G, S5E). We next evaluated whether this antibody differentially immunostained brain tissue from patients with clinically and pathologically confirmed FXTAS. Immunostaining with 2J7 was much more robust in FXTAS patient-derived hippocampal sections than in control tissue sections and included nuclear and peri-nuclear aggregates in FXTAS sections not seen in controls (Fig. 5H, S5A). In FXTAS hippocampus, numerous ubiquitin-positive inclusions were observed (Fig. S6B), consistent with previous reports (Greco et al., 2006), and these inclusions co-immunostain with 2J7 (Fig. 5I, S5B–D). In contrast, 2J7 did not immunostain ubiquitinated polyglutamine inclusions in SCA 3 patient tissues (Fig. 5I, S6E). Similar staining by western blot and immunohistochemistry was observed using a different monoclonal antibody (2C13) against an overlapping epitope (Figure S5F–L).

We also generated an additional rabbit polyclonal antibody Ab605 raised against a larger peptide fragment of FMRpolyG (Fig. 5B). This antibody also recognizes the recombinant protein (Fig. 5J). To evaluate whether Ab605 recognizes FMRpolyG in inclusions in tissue, we first tested it on transverse retinal sections of Drosophila expressing the full antibody epitope. In flies expressing (CGG)90 GFP, Ab605 readily co-localized with GFP+ inclusions (Fig. S6A) but showed minimal staining in flies expressing GFP alone (Fig. S6A). Whereas in control human tissue Ab605 displayed mild diffuse staining not seen in pre-immune controls, Ab605 robustly stained neurons and intranuclear inclusions in FXTAS brain (Fig. 5K, S6C). By immunofluorescence, Ab605 staining co-localized with ubiquitin in FXTAS brain tissue (Fig. S6D). Recognition of FXTAS inclusions was specific, as there was no staining by Ab605 of ubiquitinated polyglutamine inclusions in tissue sections from a Spinocerebellar Ataxia 3 brain(Fig. S6E).

RAN translation of the polyglycine protein explains the difference in inclusion formation between two mouse models of FXTAS

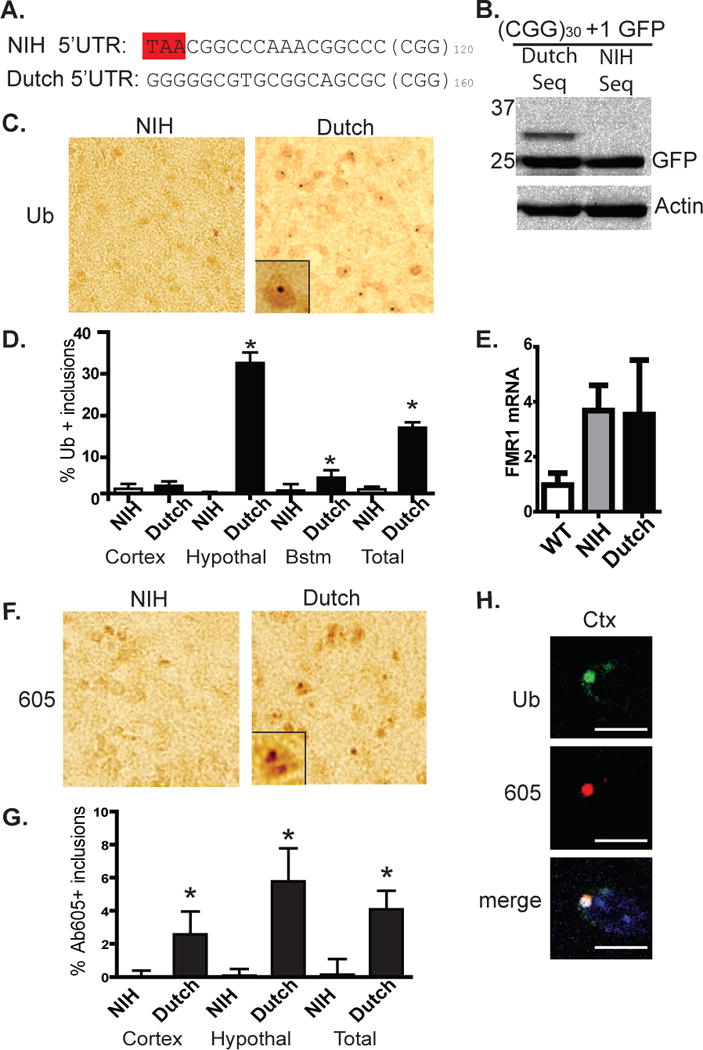

To gauge the functional consequence of expressing a cryptic polyglycine protein, we turned to two similar mouse models of FXTAS. In both models, one generated in the Netherlands (Willemsen et al., 2003) and the other at the NIH (Entezam et al., 2007), pre-mutation repeats were inserted into the 5’UTR of the mouse fmr1 locus. Both knock-in models demonstrate intra-generational repeat instability and some evidence of neurodegeneration, but their phenotypes have not been directly compared (Brouwer et al., 2008). Comparing the cloning strategies used to make both lines, we noted that the NIH mouse model retains a greater region of mouse 5’UTR surrounding the CGG repeat, including a TAA stop codon 18 bp 5’ of the repeat in the glycine frame (Fig. 6A). This stop codon is not present in the Dutch knock-in mouse or in humans. In cell culture experiments, placing the NIH mouse sequence, but not the Dutch mouse sequence, just proximal to the repeat blocked translation in the +1 (Gly) frame (Fig. 6B). Thus, we would predict expression of the novel polyglycine protein only in the Dutch knock-in mouse. Consistent with this prediction, 18 month old mice from both lines differ greatly in the number and distribution of ubiquitinated inclusions. In Dutch knock-in mice, ubiquitin-positive inclusions accumulate in the hypothalamus, cortex, and brainstem (Fig. 6C, D) as previously reported (Brouwer et al., 2008), whereas they were seen less frequently in NIH knock-in mice (Fig. 6C, D). This difference exists despite similar expression of (CGG)n fmr1 RNA in both models (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Sequence differences 5’ of the repeat explain divergent inclusion formation in two murine knock-in models of FXTAS.

A) Sequence differences in two established CGG knock-in models of FXTAS highlighting a stop codon 18 bp before the repeat present only in the NIH mouse. B) Placement of the NIH mouse sequence, but not the Dutch sequence, just 5’ to the repeat eliminates the HMW GFP species in the +1 (Gly) frame. C) Representative images (original magnification 400x, inset 1000x) of hypothalamus from 18 month old NIH and Dutch knock-in mice stained with antibody to ubiquitin. D) Quantification of ubiquitin-positive inclusions in 18 month old NIH and Dutch mice in the specified brain regions. E) Relative expression of fmr1 mRNA in WT, NIH, and Dutch mice at 6 months of age (n = 4/genotype). F) Representative images of hypothalamus from 18 month old NIH and Dutch knock-in mice stained with Ab605 against FMRpolyG. G) Quantification of 605-positive inclusions in 18 month old NIH and Dutch mice in the specified brain regions. H) Confocal microscopy in the Dutch knock-in mice showing co-localization of ubiquitin and Ab605 staining inclusion in frontal cortex (left images). For D, n > 300 cells/brain region and > 1000 cells/genotype, *p > 0.01 on Pearson’s chi-squared test. Error bars represent 95% CI.

Because Ab605 was raised against a peptide sequence largely conserved in mouse, we used it to determine whether there is divergent immunostaining for FMRpolyG protein in the two models. Again, Dutch knock-in mice show much greater immunostaining for FMRpolyG, including punctate nuclear staining consistent with inclusions in brain regions that also display ubiquitin-positive inclusions (Fig. 6F, G). By co-immunofluorescence, Ab605 staining for FMRpolyG in Dutch knock-in mice co-localized with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (Fig. 6H). Together, these data suggest a dissociation of pathology in the two models based on differences in the ability to generate the polyglycine protein.

Translation of the polyglycine protein contributes to CGG repeat toxicity in human cell lines and Drosophila

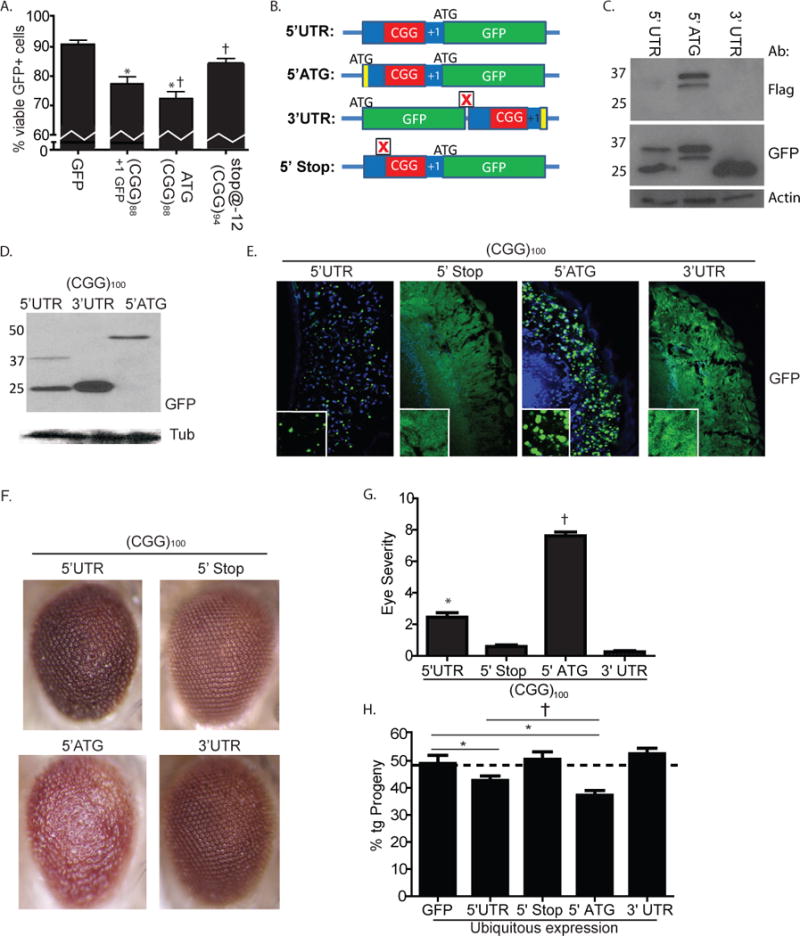

The above results demonstrating RAN translation of a polyglycine protein in FXTAS models and patients support a role for FMRpolyG in aggregate formation in FXTAS. A critical, unanswered question is whether this polyglycine protein contributes to disease pathogenesis in FXTAS, or whether instead the CGG repeat as mRNA is wholly responsible for repeat associated neurodegeneration. We therefore evaluated the effect of driving translation through the repeat on cell viability. Compared to expression of GFP alone, (CGG)88 +1 GFP expression was associated with increased cell death at 72 hours, as measured by propidium iodide exclusion in GFP-positive cells (Fig. 7A). This toxicity was repeat length-dependent (Fig. S2E), consistent with previous reports (Arocena et al., 2005; Sellier et al., 2010). When translation of the polyglycine protein was enhanced by placing an ATG upstream of the repeat, which increases production of the polyglycine protein without altering (CGG) GFP mRNA levels, the toxicity of the construct increased further (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Production of polyglycine protein from CGG repeat RNA constructs correlates with toxicity in Drosophila models.

A) COS cell viability 72 hrs after transfection of (from left to right) GFP alone, (CGG)88 +1 (Gly) GFP, ATG-FLAG-(CGG)88 +1 (Gly) GFP, or Stop@-12(CGG)94 +1 (Gly) GFP. * p < 0.05 vs. GFP alone; † p < 0.05 vs. (CGG)88 GFP. B) Schematic of pUAST constructs used to generate fly lines with differing amounts of polyglycine protein production but identical (CGG) repeat RNA expansions. Full sequences are shown in Table S2. Boxed red X = stop codon, green = GFP, Red = CGG repeat, blue = other sequence. Yellow = epitope tag (Flag or 6xHis tag). C) Placing the CGG repeat in the 3’UTR of GFP eliminates the RAN translation product. COS cells were transiently transfected with either GFP (– control), ATG-FLAG-(CGG)88 +1 GFP (+ control) or GFP-STOP-(CGG)88-FLAG and total lysates were harvested. Blots were serially probed with antibodies to FLAG, GFP, and actin. D) Lysates from Drosophila lines expressing the described constructs were probed with GFP or Tubulin. The higher MW of the ATG construct results from 150nt of intervening sequence between the start codon and the start of the (CGG)100 repeat. E) GFP inclusion formation in Drosophila eye cross sections of the indicated genotypes. F) Representative images of eyes 1–2 days post eclosion with the indicated genotypes demonstrate differential toxicity across lines that is dependent on polyglycine translation. G) Quantification of the rough eye phenotypes associated with the indicated genotypes demonstrates significantly enhanced toxicity in lines with enhanced polyglycine translation and impaired toxicity in lines where CGG RAN translation is blocked. H) Ubiquitous expression of CGG GFP transgenes in the 5’UTR decreases fly viability as measured by progeny eclosion ratios. This change in viability is blocked in CGG 5’stop lines and CGG 3’UTR lines but the constructs are more toxic in ATG-CGG GFP lines where polyglycine protein production is enhanced. For G and H, * p < 0.05 vs. 3’UTR or GFP; † p < 0.05 vs. 5’UTR.

Because introducing a stop codon just before the repeat eliminated production of HMW GFP, we reasoned that this construct might allow us to determine whether initiating RAN translation is required for repeat associated toxicity. Computer modeling of the FMR1 5’UTR RNA secondary structure predicts an energetically favorable hairpin that includes the CGG repeat (Fig. S3, (Napierala et al., 2005). Placement of a stop codon at −12bp relative to the repeat is not predicted to disrupt this hairpin (Fig. S3), suggesting that CGG repeat structure should be preserved in this construct. We therefore measured cell death in transfected cells expressing (CGG)88 +1 GFP or a similar (CGG)94 +1 GFP construct containing a stop codon 12 bp before the repeat. Inclusion of this stop codon suppressed toxicity associated with the CGG repeat expansion, suggesting that a component of repeat toxicity reflects production of a polyglycine protein (Fig. 7A).

To evaluate these effects in vivo, we generated a series of Drosophila lines in which the repeat was placed in different sequence contexts relative to GFP (Fig. 7B, Table S2). We first regenerated lines in which the CGG repeat in the 5’UTR of FMR1 is inserted upstream of GFP in the +1 (Gly) reading frame. In other lines we inserted an ATG and FLAG tag just upstream of the CGG repeat to maximally drive expression of the polyglycine protein. To generate constructs in which the CGG repeat would be present as RNA but not translated into protein, we took two approaches: 1) inserting a stop codon 12nt 5’ of the CGG repeat to prevent repeat associated translation of the polyglycine protein; as shown earlier in cell culture (Fig. 3D); or 2) moving the CGG repeat and surrounding regions of the 5’UTR to a position downstream of GFP in the 3’UTR. In cell culture, this repositioning blocked RAN translation (Fig. 7C). All Drosophila lines expressed 100 CGG repeats, which were stable with intergenerational transmission.

Differential placement of the CGG repeat modestly altered transcript expression in Drosophila, with increased GFP mRNA in lines containing the repeat in the 5’UTR (Fig. S7A), perhaps due to local chromatin effects (Todd et al., 2010). Accordingly, we chose for further analysis lines in which GFP RNA production was comparable (Fig. S7A). At the protein level, placing the CGG repeat in the 5’UTR led to less overall GFP translation than did placement in the 3’UTR (Fig. 7D). As expected, including an ATG start codon upstream of the repeat led to increased production of HMW GFP but decreased production from the canonical TIS of GFP (Fig. 7D).

To determine the impact of polyglycine protein expression on neurodegenerative phenotypes, we expressed each transgene in retinal oomatidia. In flies expressing the repeat in the 5’ UTR, we again observed the appearance of ubiquitin-positive GFP inclusions which occurred more frequently when an ATG was placed upstream of the repeat (Fig. 7E). In lines with a stop codon 5’ to the repeat or with the repeat positioned in the 3’UTR, there were no GFP inclusions.

We next determined whether expression of these different transgenes elicited a rough eye phenotype as a measure of toxicity. Placing the repeat in the 5’UTR and in-frame with GFP resulted in a moderate rough eye phenotype (Fig. 7F, G and S8C), but this same repeat elicited only a very mild rough eye phenotype when inserted into the 3’UTR of GFP. Similarly, inserting a stop codon just 5’ to the repeat suppressed toxicity (Fig 7F, G and S7C). In contrast, when an ATG was included 5’ to the repeat to drive polyglycine production, the rough eye phenotype was more severe (Fig. 7F, G). These results were consistent across multiple insertion lines (Fig S7C). When expressed ubiquitously, CGG repeat splaced in the 5’UTR of GFP led to a decrease in viable progeny, and inclusion of an ATG 5’ of the repeat further enhanced this toxicity (Fig. 7H). In contrast, including a stop codon 5’ of the repeat or placing the repeat in the 3’UTR prevented CGG repeat associated alterations in viability (Fig. 7H). Together, these results suggest that RAN translation of a polyglycine protein contributes to CGG repeat toxicity in Drosophila.

Discussion

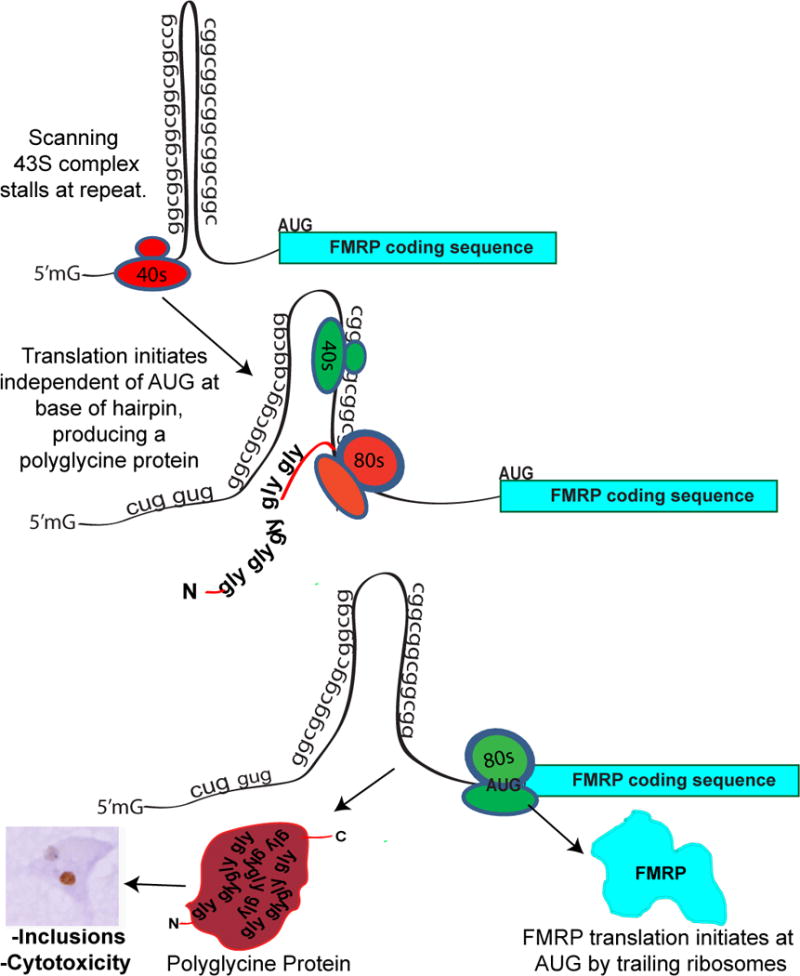

Our results demonstrate that RAN translation occurs in association with CGG repeats in the neurodegenerative disorder FXTAS, a disease previously thought to result primarily from RNA mediated toxicity. These findings, along with recent reports detailing unconventional translation through CAG repeats in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8 and Myotonic dystrophy Type I (Zu et al., 2010) and GGGGCC repeats in C9orf72 associated ALS/FTLD (Ash et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013), suggest that RAN translation is a shared pathogenic mechanism in many repeat expansion disorders. We further demonstrate that production of one particular CGG RAN translation product in FXTAS, FMRpolyG, directly modulates CGG associated pathology in two distinct model systems. First, the ability to generate the FMRpolyG protein explains a key pathologic discrepancy between two established knock-in mouse models. Second, in Drosophila we demonstrate that CGG repeat associated neurodegeneration is largely dependent on FMRpolyG production. These results suggest that RAN translation contributes to FXTAS pathogenesis (Fig. 8) and support an emerging view that non-exonic repetitive elements can trigger toxicity simultaneously as both RNA and protein.

Figure 8. Model for CGG RAN translation in fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome.

Ribosomes assemble on the 5’ end of the FMR1 message and scan the mRNA for an appropriate initiation sequence. Near the CGG repeat hairpin, the 43S preinitiaton complex (red) stalls, triggering RAN translational initiation. Once translation initiates, the ribosome reads through the repeat to produce a polyglycine-containing protein. Normally, this peptide is readily cleared from cells, but with larger repeats the resultant expanded polyglycine protein accumulates in inclusions. The downstream AUG start site for FMRP is not in frame with the polyglycine protein, thus no N-terminal addition onto FMRP occurs with this CGG RAN translation. Trailing ribosomes (green) may not stall at the hairpin but instead initiate translation normally at the AUG for FMRP.

The mechanisms underlying RAN translation remain unclear. The unconventional translation described here appears to initiate predominantly at a near AUG-codon just 5’ proximal of the repeat. This finding suggests a model wherein a scanning 43S ribosomal pre-initiation complex stalls at the CGG repeat, allowing for alternate usage of a near-match at the initiation codon (Fig. 8). This model is based on our observation that placing a stop codon just proximal to the repeat or shortening the 5’ leader before the repeat impairs RAN translation in this reading frame (Fig 3). In contrast, CGG RAN translation in the other two possible reading frames behaves differently. We do not detect any RAN translation product from the +0 (CGG, polyArginine) reading frame, and RAN translation in the +2 (GCG, polyAlanine) reading frame is less efficient, occurs when stop codons are inserted 5’ of the repeat, and demonstrates CGG repeat length dependence (Figures 3–5). Differences in the propensity for translational initiation in different reading frames was also reported for RAN translation of expanded CAG repeats in SCA 8 in which the surrounding sequence appeared to be an important modulator (Zu et al., 2010). Thus, RAN translation may not result from a single mechanism. Rather each repeat, and indeed each reading frame within each repeat, may have different contextual requirements. These differences notwithstanding, the fact that atypical translation has now been observed independently with four different nucleotide RNA repeats in cell lines, animal models, and human tissues suggests it is a more widespread biological event than anticipated.

An emerging question now is, what roles do these novel translation initiation events play in normal physiology and in disease? Our findings support a significant role for the FMRpolyG protein in disease pathogenesis, given the evidence in Drosophila and mammalian cells of enhanced toxicity with increased polyglycine translation and lessened toxicity when translation is reduced. However, numerous published studies support a primary role for CGG RNA in toxicity (Arocena et al., 2005; Hashem et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2007; Sellier et al., 2010; Sofola et al., 2007), leading us to suggest that, in FXTAS, additive or synergistic toxicity associated with both toxic RNA and toxic proteins may be critical to disease pathogenesis. Though we have focused on FMRpolyG production, other CGG RAN translation associated products such as the polyalanine protein could represent additional toxic species. Moreover, if RAN translation occurs with CCG repeats, then production of other homopolymeric proteins from the antisense transcript through the repeat could also be relevant (Ladd et al., 2007). For all of these potentially toxic entities, it will be important to determine their relative production in patients and relative degree of toxicity in animal models to ascertain their roles in disease pathogenesis.

CGG RAN translation may also play a normal physiological role in translational regulation of FMR1 mRNA. FMRP, the protein product of FMR1, critically regulates synaptic function and its loss leads to Fragile X Syndrome, a common cause of autism and mental retardation. FMR1 mRNA is rapidly translated at synapses in an activity-dependent manner, where it constrains local synaptic protein translation (Penagarikano et al., 2007). Our results in transfected cells show that RAN translation can occur at normal repeat sizes, with initiation occurring within a narrow region just 5’ of the repeat (Fig. 8). Analysis of ribosomal profiling datasets derived from samples with normal CGG repeat sizes demonstrates the presence of assembled ribosomes over these regions in both human and mouse cell lines (Fig. 5, S5 and (Ingolia et al., 2011)). Intriguingly, the Drosophila homologue of FMRP, dfxr, is expressed as two isoforms, with the larger isoform initiating translation at a CUG codon upstream of the canonical TIS, indicating that aspects of this process may be evolutionarily conserved (Beerman and Jongens, 2011). Upstream ORFs are believed to suppress expression from downstream canonical ORFs (Chatterjee and Pal, 2009). In the case of FMR1 mRNA, translation through the repeat may assist RNA unwinding via helicase recruitment, allowing normal scanning by trailing ribosomes and appropriate initiation at the canonical ORF (Fig. 8) . Alternatively, ribosomes translating through the repeat could terminate translation and re-initiate at the AUG of FMRP, or ribosomes could initiate downstream of the repeat via an internal ribosomal entry site (Ludwig et al., 2011).

Variations on the RAN translation described here potentially could expand the percentage of the transcriptome encoding for protein, complicating the classical definitions by which we divide “coding” from “non-coding” RNA. Consistent with this, recent unbiased methods in yeast and mammalian cells reveal that thousands of transcripts initiate translation at non-AUG start sites, often creating upstream ORFs in sequences previously identified as 5’UTR (Ingolia et al., 2011; Ivanov et al., 2011). Usage of these atypical upstream ORFs are responsive to changes in cell state and external stimuli (Brar et al., 2012). Mechanisms similar to those reported here may therefore have broader repercussions for the neuronal proteome and global translational regulation.

Methods

Fly stocks

Drosophila lines used in figures 1–3 of this study have been previously described (Jin et al., 2003; Pandey et al., 2007; Todd et al., 2010). Details of construction of new fly lines are in the supplemental methods and Table S2. Unless stated otherwise, all crosses were done and maintained on standard food at 250C. For (CGG)90 GFP lines, stability of the CGG repeat was confirmed by PCR and sequencing using C and F primers.

Plasmid constructs for cell culture experiments

Cell culture expression plasmids were derived from CMV-(CGG)88-GFP, a kind gift from Paul Hagerman (Arocena et al., 2005) or were PCR cloned from patient derived cell lines. Sequence variants were generated from this vector by site directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) according to manufacturer’s protocols. All vector sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and are described in detail in Table S1.

Lysostaphin protease digestion

Immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP agarose beads was conducted as described in the supplemental methods. Prior to elution, the beads were washed 2x in RIPA without protease inhibitors and then in 20mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.5 without protease inhibitors. The agarose beads were then incubated with 0.1mg/mL Lysostaphin (Sigma) in tris buffer or in tris buffer alone with agitation at room temperature for 3 or 20 hours. The beads were then washed 1×5 min with RIPA buffer and eluted with Laemmli buffer.

Antibody generation

Monoclonal mouse antibodies 2J7 and 2C13 were developed commercially (Abmart) against a 10 amino acid peptide, LAGLKRRWRS, in the predicted carboxyl terminus of the FMR1polyG. The epitope is predicted to be present in human patient samples, with a near match (8/10 AA) to the original (CGG)90 GFP Drosophila lines, but not the newly constructed Drosophila lines or the transfection vector constructs used in figures 3–5. The epitope is effectively absent (5/10 AA match) from both mouse KI models. Rabbit polyclonal antibody Ab605 was generated commercially (Rockland) against a larger peptide (GLKRRWRSWWWKCGAP) that overlaps more significantly with the predicted sequence in Drosophila (16/17) and in both mouse lines (13/17).

Human Tissue

Detailed methods and descriptions of the patient derived samples are included in the supplemental methods. Briefly, hippocampal, cerebellar and frontal cortex tissue from two previously described FXTAS patients (Louis et al., 2006) and age and sex matched controls (University of Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Bank) were processed using standard techniques. CGG repeat size was determined in both controls and FXTAS patients by DNA isolation followed by PCR using C and F primers.

Statistical Analysis

For graphs of percentages, error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. For all other graphs, error bars represent standard error of the mean. For statistical analyses of non-parametric measurements of viability and inclusions, a chi squared test was performed. For all other analyses, a one way ANOVA was performed, with post-hoc Dunnet’s test for multiple comparisons when applicable. Ribosomal profiling dataset analysis is detailed in Supplemental methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Peng Jin for providing (CGG)90-GFP fly lines, Karen Usdin for providing (CGG)120 KI “NIH” mice and David Nelson and the Fragile X mutant mouse facility for providing (CGG)160 KI “Dutch” mice (originally generated by Rob Willemsen in Erasmus, The Netherlands), Paul Hagerman for sharing plasmids and patient tissue samples, Zhe Han and Jinghan Cheng for fly resources and technical assistance. This work was funded by KNS069809A to PKT NAF postdoctoral fellowship to HF and RO1 NS038712, RO1 AG034228, and research funds from the Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Center to HLP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arocena DG, Iwahashi CK, Won N, Beilina A, Ludwig AL, Tassone F, Schwartz PH, Hagerman PJ. Induction of inclusion formation and disruption of lamin A/C structure by premutation CGG-repeat RNA in human cultured neural cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3661–3671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash PE, Bieniek KF, Gendron TF, Caulfield T, Lin WL, Dejesus-Hernandez M, van Blitterswijk MM, Jansen-West K, Paul JW, 3rd, Rademakers R, et al. Unconventional Translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC Expansion Generates Insoluble Polypeptides Specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman RW, Jongens TA. A non-canonical start codon in the Drosophila fragile X gene yields two functional isoforms. Neuroscience. 2011;181:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar GA, Yassour M, Friedman N, Regev A, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS. High-resolution view of the yeast meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling. Science. 2012;335:552–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1215110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Huizer K, Severijnen LA, Hukema RK, Berman RF, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. CGG-repeat length and neuropathological and molecular correlates in a mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1671–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell. 2009;101:251–262. doi: 10.1042/BC20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Tassone F, Sahota P, Hagerman PJ. The (CGG)n repeat element within the 5′ untranslated region of the FMR1 message provides both positive and negative cis effects on in vivo translation of a downstream reporter. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. RNA and disease. Cell. 2009;136:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entezam A, Biacsi R, Orrison B, Saha T, Hoffman GE, Grabczyk E, Nussbaum RL, Usdin K. Regional FMRP deficits and large repeat expansions into the full mutation range in a new Fragile X premutation mouse model. Gene. 2007;395:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch C, Herrmann A, Nothnagel M, Szafranski K, Huse K, Schumann F, Schreiber S, Platzer M, Krawczak M, Hampe J, et al. Genome-wide search for novel human uORFs and N-terminal protein extensions using ribosomal footprinting. Genome Res. 2012;22:2208–2218. doi: 10.1101/gr.139568.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Berman RF, Martin RM, Tassone F, Schwartz PH, Chang A, Trapp BD, Iwahashi C, Brunberg J, Grigsby J, et al. Neuropathology of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Brain. 2006;129:243–255. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa V, Goldwater D, Stiles D, Cam M, Poy G, Kumari D, Usdin K. Long CGG-repeat tracts are toxic to human cells: implications for carriers of Fragile X premutation alleles. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2702–2708. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashem V, Galloway JN, Mori M, Willemsen R, Oostra BA, Paylor R, Nelson DL. Ectopic expression of CGG containing mRNA is neurotoxic in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, Ingolia NT, Janes MR, Sher A, Shi EY, Stumpf CR, Christensen C, Bonham MJ, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TW, Schuhardt VT. Lysostaphin-induced, osmotically fragile Staphylococcus aureus cells. J Bacteriol. 1970;103:116–119. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.1.116-119.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Brar GA, Rouskin S, McGeachy AM, Weissman JS. The ribosome profiling strategy for monitoring translation in vivo by deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1534–1550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov IP, Firth AE, Michel AM, Atkins JF, Baranov PV. Identification of evolutionarily conserved non-AUG-initiated N-terminal extensions in human coding sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4220–4234. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi CK, Yasui DH, An HJ, Greco CM, Tassone F, Nannen K, Babineau B, Lebrilla CB, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Protein composition of the intranuclear inclusions of FXTAS. Brain. 2006;129:256–271. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Leehey MA, Hall DA, Levine RA, Brunberg JA, Zhang L, Jardini T, Gane LW, Harris SW, et al. Penetrance of the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome in a premutation carrier population. JAMA. 2004;291:460–469. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Duan R, Qurashi A, Qin Y, Tian D, Rosser TC, Liu H, Feng Y, Warren ST. Pur alpha binds to rCGG repeats and modulates repeat-mediated neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Neuron. 2007;55:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Zarnescu DC, Zhang F, Pearson CE, Lucchesi JC, Moses K, Warren ST. RNA-mediated neurodegeneration caused by the fragile X premutation rCGG repeats in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;39:739–747. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd PD, Smith LE, Rabaia NA, Moore JM, Georges SA, Hansen RS, Hagerman RJ, Tassone F, Tapscott SJ, Filippova GN. An antisense transcript spanning the CGG repeat region of FMR1 is upregulated in premutation carriers but silenced in full mutation individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3174–3187. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Liu B, Huang SX, Shen B, Qian SB. Global mapping of translation initiation sites in mammalian cells at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2424–2432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207846109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leehey MA, Berry-Kravis E, Goetz CG, Zhang L, Hall DA, Li L, Rice CD, Lara R, Cogswell J, Reynolds A, et al. FMR1 CGG repeat length predicts motor dysfunction in premutation carriers. Neurology. 2008;70:1397–1402. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000281692.98200.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Yu Z, Teng X, Bonini NM. RNA toxicity is a component of ataxin-3 degeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature06909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E, Moskowitz C, Friez M, Amaya M, Vonsattel JP. Parkinsonism, dysautonomia, and intranuclear inclusions in a fragile X carrier: a clinical-pathological study. Mov Disord. 2006;21:420–425. doi: 10.1002/mds.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig AL, Hershey JW, Hagerman PJ. Initiation of translation of the FMR1 mRNA Occurs predominantly through 5′-end-dependent ribosomal scanning. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Weng SM, Arzberger T, May S, Rentzsch K, Kremmer E, Schmid B, Kretzschmar HA, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C, et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC Repeat Is Translated into Aggregating Dipeptide-Repeat Proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1232927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley ML, Zu T, Ikeda Y, Gao W, Mosemiller AK, Daughters RS, Chen G, Weatherspoon MR, Clark HB, Ebner TJ, et al. Bidirectional expression of CUG and CAG expansion transcripts and intranuclear polyglutamine inclusions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8. Nat Genet. 2006;38:758–769. doi: 10.1038/ng1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napierala M, Michalowski D, de Mezer M, Krzyzosiak WJ. Facile FMR1 mRNA structure regulation by interruptions in CGG repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:451–463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oma Y, Kino Y, Sasagawa N, Ishiura S. Intracellular localization of homopolymeric amino acid-containing proteins expressed in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21217–21222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey UB, Nie Z, Batlevi Y, McCray BA, Ritson GP, Nedelsky NB, Schwartz SL, DiProspero NA, Knight MA, Schuldiner O, et al. HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS. Nature. 2007;447:859–863. doi: 10.1038/nature05853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE. Repeat associated non-ATG translation initiation: one DNA, two transcripts, seven reading frames, potentially nine toxic entities! PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penagarikano O, Mulle JG, Warren ST. The pathophysiology of fragile x syndrome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:109–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron. 2011;72:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellier C, Rau F, Liu Y, Tassone F, Hukema RK, Gattoni R, Schneider A, Richard S, Willemsen R, Elliott DJ, et al. Sam68 sequestration and partial loss of function are associated with splicing alterations in FXTAS patients. EMBO J. 2010 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofola OA, Jin P, Qin Y, Duan R, Liu H, de Haro M, Nelson DL, Botas J. RNA-binding proteins hnRNP A2/B1 and CUGBP1 suppress fragile X CGG premutation repeat-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of FXTAS. Neuron. 2007;55:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stochmanski SJ, Therrien M, Laganiere J, Rochefort D, Laurent S, Karemera L, Gaudet R, Vyboh K, Van Meyel DJ, Di Cristo G, et al. Expanded ATXN3 frameshifting events are toxic in Drosophila and mammalian neuron models. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2211–2218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Iwahashi C, Hagerman PJ. FMR1 RNA within the intranuclear inclusions of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) RNA Biol. 2004;1:103–105. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 2012;485:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd PK, Oh SY, Krans A, Pandey UB, Di Prospero NA, Min KT, Taylor JP, Paulson HL. Histone deacetylases suppress CGG repeat-induced neurodegeneration via transcriptional silencing in models of fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilburn B, Rudnicki DD, Zhao J, Weitz TM, Cheng Y, Gu X, Greiner E, Park CS, Wang N, Sopher BL, et al. An antisense CAG repeat transcript at JPH3 locus mediates expanded polyglutamine protein toxicity in Huntington’s disease-like 2 mice. Neuron. 2011;70:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen R, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Reis S, Holstege J, Severijnen LA, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Schrier M, van Unen L, Tassone F, Hoogeveen AT, et al. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AJ, Paulson HL. Polyglutamine neurodegeneration: protein misfolding revisited. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T, Gibbens B, Doty NS, Gomes-Pereira M, Huguet A, Stone MD, Margolis J, Peterson M, Markowski TW, Ingram MA, et al. Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;108:260–265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013343108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.