Abstract

The synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of [Fe(NO)(N3PyS)]BF4 (3) is presented, the first structural and electronic model of NO-bound cysteine dioxygenase (CDO). The nearly isostructural all-N-donor analog [Fe(NO)(N4Py)](BF4)2 (4) was also prepared, and comparisons of 3 and 4 provide insight regarding the influence of S versus N ligation in {FeNO}7 species. One key difference occurs upon photoirradiation, which causes the fully reversible release of NO from 3, but not from 4.

Mononuclear non-heme iron oxygenases utilize dioxygen to perform key oxidations in biology.1 Much effort has gone into obtaining a mechanistic understanding of these systems, including the trapping and characterization of metal-oxygen intermediates in both the proteins and synthetic models. The nitric oxide (NO•) molecule has been used as a surrogate for O2, generating Fe-NO adducts that are analogs for key Fe-O2 intermediates and helping to determine the general site(s) and requirements for O2 binding.2

Cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) is a non-heme iron oxygenase that is responsible for regulating cysteine levels in mammals by oxidizing cysteine to cysteine sulfinic acid with O2. The mechanism of CDO is still not well understood, although a number of experimental, computational, and synthetic studies have sought to address different features of the S-oxygenation process.3 Pierce and co-workers employed NO• as an O2 surrogate for CDO, and reported that, in the presence of Cys substrate, an iron-nitrosyl complex was formed (Fe(NO)(Cys)-CDO).2c This {FeNO}7 (Enemark-Feltham notation)4 complex exhibited an unusual S = ½ ground state, as opposed to all other non-heme {FeNO}7 enzymatic species, which exhibit an S = 3/2 ground state.2

A structural and functional model of CDO [FeII(N3PyS)(CH3CN)]BF4 (1), was previously described by some of us.3a Addition of O2 to 1 resulted in biomimetic S-oxygenation to give a sulfinate complex, but the mechanism of oxygenation, including the binding site for O2 to Fe, was not clarified. We herein describe the synthesis of the first model of NO-bound CDO, [Fe(NO)(N3PyS)]BF4 (3) (Scheme 1), which is an {FeNO}7 complex that exhibits the same S = ½ ground state as the enzyme. The all-nitrogen analog [Fe(NO)(N4Py)](BF4)2 (4) has also been prepared, allowing for the direct comparison of these two essentially isostructural {FeNO}7 complexes and providing insight into the effects of sulfur versus nitrogen ligation. Thiolate-ligated 3 releases NO• upon photoirradiation with visible light, and this process is highly reversible. In contrast, the all-N analog 4 exhibits no appreciable photolability. Complex 3 is a rare example of a non-heme {FeNO}7 complex that undergoes photoactivated release of nitric oxide.

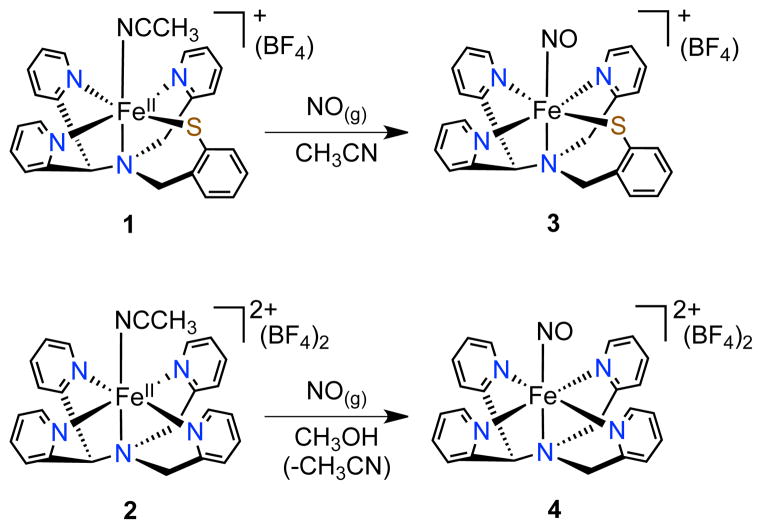

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of {FeNO}7 complexes

Stirring of the low-spin FeII complex 1 under an atmosphere of NO(g) in CH3CN gives the nitrosyl complex [Fe(NO)(N3PyS)]BF4 (3) as an analytically pure brown solid (74%) (Scheme 1). Recrystallization from CH3OH/Et2O led to crystals of 3, whose X-ray structure is shown in Figure 1. The structure reveals one molecule of NO• has displaced the CH3CN ligand and confirms that 1 readily binds NO•, providing strong support for the proposed site for O2 binding in 1 during biomimetic sulfoxygenation.3a Only one other complex ([(SMe2N4(tren))Fe(NO)]+)5 besides 3 contains the N4S ligand environment of the NO-bound form of CDO.

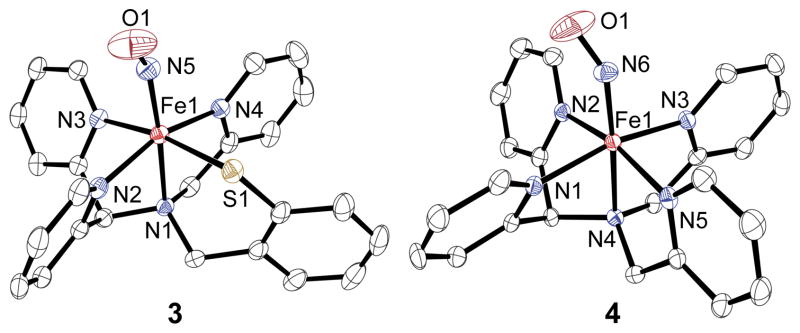

Figure 1.

Displacement ellipsoid plots (50% probability level) of the cation of 3 (left) and the dication of 4 (right). H atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Different conditions were necessary to prepare the nitrosyl complex of the all-nitrogen-ligated analog [FeII(N4Py)(CH3CN)](BF4)2 (2). Complex 2 is unreactive toward O2 in the absence of co-reductants, unlike 1.6 Similarly, no reaction was seen for 2 with the O2 surrogate NO(g) in CH3CN. However, when the latter reaction was carried out in CH3OH, an immediate color change from orange to pink was observed. Vapor diffusion of Et2O into a methanolic solution afforded orange-red X-ray quality crystals of 4 (49%). The crystal structure of 4 shows that the NO ligand has replaced the solvent molecule as expected (Figure 1).

The Fe-N(py) and Fe-N(amine) distances in 3 are significantly elongated compared to the starting CH3CN-bound complex 1, with an average increase in Fe-N bond lengths of 0.0739 Å. The Fe-N(amine) trans to the NO donor is the most affected (Fe-N1 = 1.9860(13) Å for 1; 2.1300(16) Å for 3), consistent with a strong trans influence for NO•. The influence of the NO• ligand in 4 is much less pronounced, with an average increase of only 0.0345 Å in the Fe-N bonds of 4 compared to 2. The Fe-N(O) and N-O bond lengths are almost identical for 3 and 4 (Fe-N(O) = 1.7327(18) Å for 3 and 1.732(2) Å for 4; N-O = 1.150(3) Å for 3 and 1.157(3) Å for 4), and the bent Fe-N-O angles are also in close agreement (147.2(2)° for 3 and 144.9(2)° for 4). These data are similar to other {FeNO}7 complexes.5,7,8 To our knowledge complexes 3 and 4 comprise the only known pair of structurally characterized {FeNO}7 complexes that differ by the substitution of an N versus S donor in the Fe coordination sphere. We expected that further examination of 3 and 4 would provide fundamental insights regarding the influence of S versus N coordination on {FeNO}7 complexes.

Mononuclear {FeNO}7 complexes exhibit N-O stretches in the infrared between 1607 and 1812 cm−1.8 The ATR-IR spectrum of polycrystalline 3 reveals two ν(N-O) candidate bands at 1753 and 1660 cm−1 of approximately equal intensity. Both of these bands shift upon substitution with 15N18O to 1677 and 1587 cm−1, respectively (see Supporting Information). The solution IR spectrum of 3 in CD3CN also reveals two peaks in the same range at 1733 and 1649 cm−1, however the band at 1733 cm−1 is much less intense compared to the lower energy vibration at 1649 cm−1 (15N18O: 1582 cm−1). The all-N analog 4 exhibits a single peak at 1672 cm−1 that can be assigned to ν(N-O). Although it is not known at this time why 3 exhibits two potential ν(N-O) modes,9 the lower energy peak for 3 at 1660 cm−1 is closest to that found for 4, although redshifted by 12 cm−1. The down-shift in ν(N-O) is consistent with a more electron-rich metal center for 3 arising from thiolate ligation, although the difference in charge for 3 vs 4 may also contribute to the shift.10

Further insight regarding the influence of S versus N coordination comes from electrochemical measurements on 3 and 4. In dry CH3CN, thiolate-ligated 3 shows two nicely reversible waves at E1/2 = 0.013 and E1/2 = −1.18 V vs Fc+/Fc, corresponding to the {FeNO}6/7 and the {FeNO}7/8 couples, respectively (Figure S5). For complex 4, two processes are also observed, and give E1/2 = 0.504 and −0.685 V vs Fc+/Fc. The substitution of a phenylthiolate for a pyridine N donor causes a dramatic, negative shift in the redox potentials for both processes by ≈ 500 mV. These results can be compared to the −800 mV shift for the E1/2 values of 1 versus 2.3a The thiolate donor causes a dramatic increase in the electron-rich nature of the iron center, but this affect is apparently only weakly translated to the NO ligand as seen in the vibrational data. Previous studies of {FeNO}7 complexes have shown a similar, yet stronger correlation between ν (N-O) and redox potentials upon the inclusion of an anionic donor.10

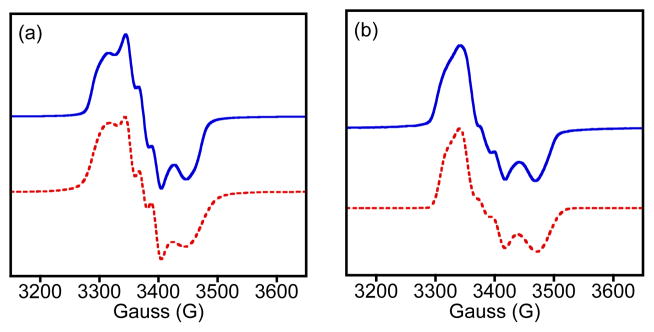

The EPR spectrum of 3 at 14 K is shown in Figure 2a. The complex has an S = ½ ground state with intense EPR signals centered near g = 2. This spectrum is distinct from S = 3/2 {FeNO}7 complexes with features at both g = 4 and g = 2. The ground state for the Cys-ligated {FeNO}7 complex of CDO is also S = ½ as seen by EPR (g 2.071, 2.022, 1.976; A(14N) = 27, 60, 28 MHz), whereas all other non-heme iron enzymes exhibit S = 3/2 upon reaction with NO.2 It was suggested that the unusual coordination environment of Fe(NO)(Cys)-CDO, which is proposed to contain a chelated Cys through S and NH2 donors, results in the unique S = ½ ground state.2c For synthetic {FeNO}7 complexes, S = ½ ground states are more common, but the only other N4S-ligated example besides 3 is S = 3/2.5 Thus complex 3, which has the same ground state as the enzyme, is the first structural and electronic model of Fe(NO)(Cys)-CDO.

Figure 2.

EPR spectra (14 K) of a) 3 (2 mM) in toluene/CH3CN and b) 4 (0.49 mM) in MeOH. Simulations (red, dashed lines) for 3: g = [2.047, 2.007, 1.962]; A(14N) = 40, 59, 40 MHz; 4: g = [2.034, 2.003, 1.950]; A(14N) = 42, 70, 35 MHz.

Substitution of the sulfur ligand for a py donor in 4 does not alter the ground state, as seen by the S = ½ EPR spectrum for 4 in Figure 2b. Both spectra for 3 and 4 were successfully simulated by including a single 14N nucleus from NO• (red line, Fig. 3). The overall shape of the spectrum and the slightly larger g anisotropy seen for 3, as compared to 4, is a better match for the data from CDO. The hyperfine splitting for 3 at gmid, which is the only experimentally well resolved A value, is also in better agreement with the enzyme.

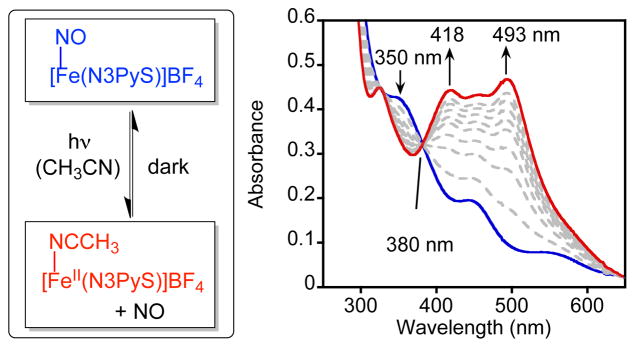

Figure 3.

Reversible dissociation of nitric oxide for 3 (left) and time-resolved UV-vis spectra (0 – 45 min) showing the conversion of [Fe(NO)(N3PyS)]+ (0.1 mM) (blue) to [FeII(N3PyS)(CH3CN)]+ (red) upon continuous photoirradiation (λ > 400 nm) in CH3CN (right).

Significant efforts have gone into elucidating the electronic distribution of {FeNO}7 complexes.10,11 For the {FeNO}7 CDO complex, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to suggest that the S = ½ species is composed of a low-spin (ls) FeII (S = 0) coupled to NO• (S = ½). For an S = 1/2 complex, there are three possible limiting electronic structures (Scheme S1): a) ls-FeII-NO•; b) ls (S = ½) FeIII–NO− (S = 0); and c) intermediate-spin (S = 3/2) FeIII-NO− (S = 1). Previously, an {FeNO}7 thiolate complex was found to have structure (c), but this complex is 5-coordinate (5C), in contrast to the 6C structures for Fe(NO)(Cys)-CDO and 3 and 4. The stronger 6C ligand field should influence the redox distribution of the {FeNO}7 unit, potentially leading to electronic structure (a).11b

We employed Mössbauer spectroscopy to analyze the electronic structures of 3 and 4 together with their ls-FeII precursors 1 and 2 (Figure S7), as well as S K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) combined with computations on 3. Well-resolved quadrupole doublets are observed in the Mössbauer spectra of these complexes. Complexes 1 (δ = 0.41 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.26 mm/s) and 2 (δ = 0.40 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.27 mm/s) give parameters consistent with ls-FeII. Conversion to the NO-bound complexes 3 (δ = 0.32 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.44 mm/s) and 4 (δ = 0.24 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.37 mm/s) leads to decreases in the isomer shift by 0.09 and 0.16 mm/s, respectively, and increases in the magnitude of the quadrupole splittings by 0.18 and 0.10 mm/s, respectively. The S K-edge XAS data of 3 (Figures S8 – S9) reveal two pre-edge features at 2470.3 eV and 2471.3 eV, assigned as transitions from S 1s → Fe d orbitals, and two features in the edge at 2472.8 eV and 2473.6 eV assigned as S 1s → C-S π*/σ* transitions. DFT calculations (see Supporting Information) were performed on 3, and the geometric structure matches the experimental crystal structure (Table S1). Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations performed on the optimized structure reasonably reproduce the energy splittings and relative intensity of the experimental S K-edge XAS of 3 (Figure S8, inset). DFT-derived Mössbauer parameters using the B3LYP functional (δ = 0.36 mm/s, ΔEQ = −0.42 mm/s) are also in good agreement with experiment.

The good agreement of DFT with experiment suggests that the DFT-derived electronic structure is a reasonable description of complex 3. As shown in Table S2, the spin density is mostly localized on the NO (α spin density of NO = 0.7, Fe = 0.3). The electronic structure is consistent with a ground state composed mostly of ls-FeII (S = 0) coupled to NO• (S = ½), with some mixing of ls-FeIII (S = ½) coupled to NO− (S = 0) character (Table S3). This electronic structure is similar to the DFT-supported ls-FeII-NO• assignment for CDO and prompts further spectroscopic characterization of the enzyme.

The controlled binding and release of NO with biologically relevant iron centers is of interest because of the key role of NO as a biological messenger and because of the intense interest in designing metal complexes as agents for NO-sensing or photodynamic therapy (PDT).12 Complexes 3 and 4 were therefore evaluated for their ability to reversibly bind NO•. Qualitative observations showed that complex 3 was quite stable to NO• release even when solutions of 3 in CH3CN were evaporated to dryness under vacuum. On the contrary, simple dissolution of 4 in CH3CN leads to the irreversible displacement of the NO• ligand to regenerate 2. Successful release of the nitrosyl ligand from 3 was induced by photoirradiation with visible light (λ > 400 nm, 150 W halogen lamp) in CH3CN in a sealed cuvette. Efficient release of NO• from 3 occurs with isosbestic conversion to yield CH3CN-bound 1 (90%) (Figure 3). Removal of the light source results in the quantitative regeneration of nitrosyl-ligated 3 (90%) via re-binding of the released NO• (Figure S10). Multiple cycles of photoirradiation with subsequent re-binding of NO• occurred without apparent decomposition of [Fe(N3PyS)]+ (Figure S11). In contrast, heating of 3 to 55 °C for 20 min causes no significant change in the UV-vis spectrum, confirming that dissociation of NO• cannot be thermally activated. Complex 4 does not release NO• in MeOH to any appreciable extent under the same photoirradiation conditions (Figure S12). Thus complex 3 exhibits completely reversible photorelease of NO• under mild conditions, as opposed to 4, which undergoes only irreversible, solvent-induced NO• substitution in CH3CN.

The photo or thermal release of NO• has been observed previously for non-heme metal-nitrosyl complexes, but these complexes are {M-NO}6 (M = Fe, Ru, Mn) species, or in some cases iron-sulfur clusters with multiple NO ligands.13 To our knowledge, complex 3 is the first example of a photolabile non-heme {M-NO}7 complex. In addition, efficient photorelease from 3 is induced under low-intensity visible light, which is highly desirable for biological applications.12 Earlier work on a set of pentadentate pyridyl/carboxamido {FeNO}6/7 complexes showed that the {FeNO}6 complex was photolabile, while the isostructural {FeNO}7 analog was not.13d The former results, combined with the lack of photolability seen for the all-nitrogen-ligated 4, suggest that the N3PyS ligand imparts special features to the {FeNO}7 unit that allow for NO photorelease, and implicates the inclusion of the unique thiolate donor as a key to this process. Further detailed experimental and computational studies are warranted to elucidate the origins of the photolability seen for 3.

In summary, the first model complex of the nitrosyl adduct for CDO was prepared. This complex exhibits the same unusual S = 1/2 ground state as seen for the enzyme, and spectroscopic and computational work indicate that the electronic structure is best described as ls-FeII (S = 0) coupled to NO• (S = ½), with some mixing of ls-FeIII (S = ½) coupled to NO− (S = 0) character. Further spectroscopic studies on NO-bound CDO and analogous models would help clarify the electronic structure of the enzyme. Complex 3 is the first example of a photolabile non-heme {M-NO}7 species, implicating the importance of thiolate donation for photorelease, and providing the foundation for the potential design of a new class of NO-releasing/sensing agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NIH (GM62309) (D.P.G.), (P41GM103393) (KOH), and (GM40392) (E.I.S.) are acknowledged for financial support and A.C.M. thanks the Harry and Cleio Greer Fellowship. G.N.L.J. thanks the Marsden Fund and The International Mobility Fund administered by Royal Society of New Zealand.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Syntheses, spectroscopy, DFT, X-ray crystallographic files (CIF), and XAS acknowledgment. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

No competing financial interests have been declared.

References

- 1.(a) Feig AL, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 1994;94:759. [Google Scholar]; (b) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Chem Rev. 2004;104:939. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McQuilken AC, Goldberg DP. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:10883. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30806a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Clay MD, Cosper CA, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, Johnson MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Orville AM, Chen VJ, Kriauciunas A, Harpel MR, Fox BG, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4602. doi: 10.1021/bi00134a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pierce BS, Gardner JD, Bailey LJ, Brunold TC, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8569. doi: 10.1021/bi700662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) McQuilken AC, Jiang YB, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8758. doi: 10.1021/ja302112y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Badiei YM, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1274. doi: 10.1021/ja109923a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiang YB, Widger LR, Kasper GD, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12214. doi: 10.1021/ja105591q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Crawford JA, Li W, Pierce BS. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10241. doi: 10.1021/bi2011724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kumar D, Sastry GN, Goldberg DP, de Visser SP. J Phys Chem A. 2012;116:582. doi: 10.1021/jp208230g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kumar D, Thiel W, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3869. doi: 10.1021/ja107514f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Gonzalez-Ovalle LE, Quesne MG, Kumar D, Goldberg DP, de Visser SP. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:5401. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25406a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Simmons CR, Krishnamoorthy K, Granett SL, Schuller DJ, Dominy JE, Jr, Begley TP, Stipanuk MH, Karplus PA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11390. doi: 10.1021/bi801546n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Sallmann M, Siewert I, Fohlmeister L, Limberg C, Knispel C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:2234. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Cho J, Woo J, Nam W. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11112. doi: 10.1021/ja304357z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Che X, Gao J, Liu YJ, Liu CB. J Inorg Biochem. 2013;122:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Tchesnokov EP, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. Biochemistry. 2012;51:257. doi: 10.1021/bi201597w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Siakkou E, Rutledge MT, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2011;1814:2003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enemark JH, Feltham RD. Coord Chem Rev. 1974;13:339. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villar-Acevedo G, Nam E, Fitch S, Benedict J, Freudenthal J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1419. doi: 10.1021/ja107551u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Lubben M, Meetsma A, Wilkinson EC, Feringa B, Que L., Jr Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1995;34:1512. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong S, Lee YM, Shin W, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13910. doi: 10.1021/ja905691f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang CY, Miller ML, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10867. doi: 10.1021/ja049627y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCleverty JA. Chem Rev. 2004;104:403. doi: 10.1021/cr020623q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The second ν(NO) mode is not due to contamination from {FeNO}6, which typically show ν(NO) > 1800 cm−1. A spin state change could give rise to two bands, but preliminary EPR data at 80 K reveals only a S = 1/2 species (see main text).

- 10.(a) Berto TC, Speelman AL, Zheng S, Lehnert N. Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:244. [Google Scholar]; (b) Goodrich LE, Paulat F, Praneeth VKK, Lehnert N. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:6293. doi: 10.1021/ic902304a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Brown CA, Pavlosky MA, Westre TE, Zhang Y, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:715. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun N, Liu LV, Dey A, Villar-Acevedo G, Kovacs JA, Darensbourg MY, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:427. doi: 10.1021/ic1006378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diebold AR, Brown-Marshall CD, Neidig ML, Brownlee JM, Moran GR, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18148. doi: 10.1021/ja202549q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Brown CD, Neidig ML, Neibergall MB, Lipscomb JD, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7427. doi: 10.1021/ja071364v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schenk G, Pau MYM, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:505. doi: 10.1021/ja036715u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hauser C, Glaser T, Bill E, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4352. [Google Scholar]; (g) Li M, Bonnet D, Bill E, Neese F, Weyhermüller T, Blum N, Sellman D, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:3444. doi: 10.1021/ic011243a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Serres RG, Grapperhaus CA, Bothe E, Bill E, Weyhermüller T, Neese F, Wieghardt K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5138. doi: 10.1021/ja030645+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Ford PC, Lorkovic IM. Chem Rev. 2002;102:993. doi: 10.1021/cr0000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ford PC, Bourassa J, Miranda K, Lee B, Lorkovic I, Boggs S, Kudo S, Laverman L. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;171:185. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Pluth MD, Lippard SJ. Chem Commun. 2012;48:11981. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37221e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Merkle AC, McQuarters AB, Lehnert N. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8047. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30464c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Patra AK, Afshar R, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2512. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2512::AID-ANIE2512>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Patra AK, Rowland JM, Marlin DS, Bill E, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:6812. doi: 10.1021/ic0301627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rose MJ, Betterley NM, Mascharak PK. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8340. doi: 10.1021/ja9004656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Rose MJ, Betterley NM, Oliver AG, Mascharak PK. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:1854. doi: 10.1021/ic902220a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hoffman-Luca CG, Eroy-Reveles AA, Alvarenga J, Mascharak PK. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:9104. doi: 10.1021/ic900604j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.