Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the i.v. administration of photosensitizers followed by illumination of the tumor with visible light leading to local production of reactive oxygen species that cause vascular shutdown and tumor cell death. Anti-tumor immunity is stimulated after PDT due to the acute inflammatory response that involves activation of the innate immune system leading to stimulation of adaptive immunity. We carried out PDT using benzoporphyrin derivative and 690-nm light after 15-minutes, in DBA/2 mice bearing either the mastocytoma, P815, that expresses the naturally occurring cancer/testis antigen P1A, or the corresponding tumor P1.204 that lacks P1A expression. Tumor cures, significantly higher survival and rejection of tumor rechallenge were obtained with P815, that were not seen with P1.204, or seen with P815 growing in nude mice. Both CD4 and CD8 T-cells had higher levels of intracellular cytokines when isolated from mice receiving PDT of P815 tumors compared to P1.204 tumors, and CD8 T-cells from P815-cured mice recognized the peptide epitope of P1A-antigen (LPYLGWLVF) using pentamer staining. Taken together, these findings show that PDT can induce a potent antigen- and epitope-specific immune response against a naturally occurring mouse tumor antigen.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, anti-tumor immunity, tumor associated antigens, cytotoxic T-cells, epitopes, cancer testis antigen

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a two-step procedure that involves the administration of a photosensitizing drug followed by activation of the drug with non-thermal light of a specific wavelength (1). The anticancer effect of PDT is a consequence of a low-to-moderately selective degree of photosensitizer (PS) uptake by proliferating malignant cells, direct cytotoxicity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and severe vascular damage that impairs blood supply to the treated area. The biological effects of PDT are considered to be limited to the particular tissue areas exposed to light. Additionally, PDT leads to activation of tumor-directed, systemic immune responses (2). PDT as a treatment procedure has been accepted by the United States Food and Drug Administration for use in endo-bronchial and endo-esophageal cancer and also as a treatment for premalignant and early malignant lesions of skin (actinic keratosis), bladder, breast, stomach and oral cavity (3).

PDT is thought to be particularly effective at activating an immune response against a locally treated tumor by effectively engaging both innate and adaptive arms of the immune systems in the host responses to cancer (2). PDT stimulates the release or expression of a mixture of pro-inflammatory and acute phase response mediators from the treated site (4–6). The local trauma that threatens the integrity of tumor microenvironment is readily recognized by the body and proinflammatory mediators are subsequently released to preserve homeostasis. As a result, a powerful acute inflammatory response, involving the accumulation of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells in large numbers at the PDT treated site is triggered (7, 8). The activation of the complement system has in particular emerged as a powerful mediator of PDT anti-tumor effects (9–13). Complement not only acts as a direct mediator of inflammation but also stimulates cells to release secondary inflammatory mediators, including cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, G-CSF, thromboxane, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, histamine, and coagulation factors (4).

To attack and eliminate malignant lesions, the immune system must employ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) that recognize tumor antigens. These are molecules that stimulate specific immunity, and are presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on the surface of target tumor cells (14). The Immune response is triggered upon epitope recognition by specific T cells through T cell receptors (TCR), after which the activated T cells exhibit cell proliferation (clonal expansion), functional differentiation, and develop effector function (15). Epitopes are groups of amino acids that are generally significantly smaller than the antigens they are derived from, and there is a possibility of a single antigen containing numerous different epitopes (although not all of them may be available for immune response).

Among various tumor antigens discovered to date three broad classes have been defined (16, 17). One is encoded by cancer-testis genes that are expressed in various tumors, but not in normal tissues (18, 19), a second is composed of differentiation antigens of the melanocytic lineage, which are present on most melanomas but also on normal melanocytes (20–22); and a third comprises antigens that appeared due to mutations in genes commonly expressed in all tissues or genes introduced to the tumor-cell genome by viruses (23–27). Immunotherapy employs various strategies to target those tumor antigens with significant degrees of success both in preclinical studies and early-phase clinical trials (28, 29).

The molecular identity of a number of both mouse and human tumor antigens has been well defined (16), the peptide sequence displayed in MHC-I molecules is known, and specific CTL lines that kill the tumor cells expressing these antigens have been produced. Furthermore, there have been efforts made to introduce defined tumor antigens into mouse tumor cell lines in order to have reproducible models to study. These model antigens are usually “foreign” proteins such as beta-galactosidase from bacteria (30), ovalbumin from chicken eggs (31), influenza hemagglutinin (HA) from a virus (32). Our laboratory was the first to recognize the role of tumor antigens in anti-tumor immune response after PDT (33). Recently, we also showed that PDT can induce a highly potent antigen specific, systemic immune response capable of causing regression in distant established tumors expressing a model tumor antigen (34).

However successful this approach may be in laboratory, artificial model tumor antigens are not clinically relevant as they cannot truly reproduce the properties of naturally occurring tumor antigens. Therefore, in this study we examined antigen specific PDT-induced anti-tumor immune response in a more clinically relevant model by employing a naturally occurring cancer antigen, namely the mouse homologue of human MAGE-type antigen termed P1A. P1A is the best-described non-mutated mouse cancer-testis tumor antigen and has been used for many immunotherapy studies (35–37). We decided to use this cancer-testis antigen, since it is well-studied and established in the literature, and is expressed in testis as well as in cancers, but not at all or at very low levels in other tissues (18, 19, 38, 39). The novelty and significance of our current study is that, in addition to using a tumor model that expresses a naturally occurring tumor antigen, thus making the study clinically relevant, we used nude mice and pentamer staining in in-vivo studies to demonstrate the epitope specific nature of the immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

P815 wild type (parental) and P1.204 (P815 derived) cell lines were a gift from Dr. Thomas Gajewski from the Department of Pathology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Cells were cultured in RPMI medium with L-glutamine and NaHCO3 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (all from Sigma, St Louis, MO) at 37°C in 5% CO2 in 75 cm2 flasks (Falcon, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

RT-PCR for P1A

Reverse transcription-PCR reactions. Total RNA from P815 and P1.204 cells was prepared using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription was done using a Reverse Transcription System at the suggested conditions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). One microgram of total RNA was used in each reaction. PCR was done using the following primers and thermal cycle conditions: 5V-CCCTTCATTGACCTCAACTACATGG-3V (glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward), 5V-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATGTC-3V (GAPDH reverse), 5V CGGAATTCTGTGCCATGTCTGATAACAAGAAA-3V (P1A forward), 5V-CGTCTAGATTGCAACTGCATGCCTAAGGTGAG- 3V (P1A reverse), 94°C × 5 minutes (94°C × 1 minute, 58°C × 1 minute, and 72°C × 1 minute) × 30 cycles, and 72°C × 7 minutes. PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide techniques.

Flow cytometry analysis of MHC class I molecules levels

P815 and P1.204 cells were fixed and incubated at room temperature (22–25°C) for 1h with PE-Conjugated anti-H2-Dd antibody (BD Pharmingen). PE Isotype antibody and unstained cells were used as controls. Cells were washed twice in 1ml of PBS and analyzed on FACScalibur (BD).

Photosensitizer and light source

Liposomal benzoporphyrin derivative mono acid ring A (Verteporfin for injection, BPD, QLT Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada) was prepared by diluting the powder to a concentration of 0.3 mg/mL in sterile 5% dextrose. A 1W 690-nm diode laser (B&W Tek Inc., Newark, DE) was coupled into a 0.8-mm diameter fiber and a lens was used to obtain a uniform spot.

In vitro PDT

5000 P815 and P1.204 cells were plated per well in 96 well plates and incubated for 1-h with 200nM BPD. After incubation the medium was replaced with 200 μL of fresh medium and PDT was performed. 690nm laser light dose was varied and fluences of 0 (dark toxicity) to 2 J/cm2 were delivered at an irradiance of 50 mW/cm2 to each well separately (4 wells represented a group). Controls entailed cells with no treatment and cells with light alone at the highest fluence or with photosensitizer alone. At the completion of the illumination, the plates were returned to the incubator for 24 h before initiating further studies. A 4-h MTT colorimetric assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used that measures mitochondrial reductase activity. This assay correlates well with colony-forming assays as a measure of cell viability, as has been described previously. The absorbance for MTT assay was read at 560 nm.

Animal tumor model

All experiments were carried out according to a protocol (number 2004N000001) approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care (IACUC) at MGH and were in accord with NIH guidelines. DBA/2 and BALB/c Nu/Nu mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Boston MA). Mice were inoculated with 350,000 cells subcutaneously into the depilated right thigh. Two orthogonal dimensions (a and b) of the tumor were measured 2–3 times a week with vernier calipers. Tumor volumes were calculated as follows, volume = 4π/3 × ((a+b)/4)3. When tumors reached a diameter of 5–7 mm (9 days after inoculation) PDT was performed.

PDT and tumor response

Tumor bearing mice were anaesthetized with i.p. injection of 87.5 mg/kg of ketamine and 12.5 mg/kg xylazine and BPD (1 mg/kg in 5% dextrose solution) was administered i.v. via the supraocular plexus. Control mice received 5% dextrose only. Fifteen minutes after BPD injection illumination was performed. A total fluence of 120 J/cm2 was delivered at a fluence rate of 100 mW/cm2 with a spot diameter 1-cm covering the tumor and a border of 2–3 mm normal tissue. Mice were allowed to recover in an animal warmer after PDT and showed no adverse effects of the treatment. The mice were sacrificed when any of the tumor diameters exceeded 1.5 cm.

Rechallenge

Mice surviving ninety days after PDT were subsequently rechallenged with 350,000 cells of P815 or P1.204 in the contralateral thigh and monitored for another 60 days. Naïve control mice were inoculated with the same sample of cells to confirm tumorigenicity.

Lymphocyte preparation

Inguinal lymph nodes and spleens from mice in all experimental groups were harvested 5 days after PDT or on 14th day of experiment in control mice, homogenized and passed through a 70 μm mesh nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon) to make single cell suspensions that were used for further experiments. For each study group we used n=5 mice to extract the cells that were pooled.

Adoptive transfer

2×106 of isolated lymph node cells from control and PDT treated DBA/2 P815 tumor bearing mice were i.v. injected into BALB/c Nu/Nu mice (6–8 weeks old) immediately after inoculation with P815 tumors. Mice were monitored for tumor growth and survival as described above.

Intracellular cytokine production in splenocytes

We used a mouse intracellular cytokine kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to measure the levels of cytokines (TNF-alpha and IL-2) in the isolated splenocytes. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, single cell suspensions of splenocytes were subsequently used in the primary activation culture to stimulate production of cytokines for 4 h using Leukocyte Activation Cocktail. The splenocytes obtained from the stimulation culture were subsequently suspended in BD Pharmingen Stain Buffer and the PE-conjugated anti-IL2 or anti-TNFα antibodies were added for overnight incubation at 4C. Additionally FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibody was added. The controls included PE and FITC isotype antibodies, unstained control as well as blocking antibody. Manufacturer provided MiCK-1 Cytokine Positive Control Cells were used as positive controls.

Pentamer staining

The R-PE labeled Pro5 MHC pentamer for P1A epitope (H-2Ld, LPYLGWLVF) was a generous gift from ProImmune (Oxford, UK). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (www.proimmune.com). Briefly, 2×106 of isolated lymphocytes from P815 control and PDT treated mice were washed in a wash buffer and suspended in 50μL aliquots. Next 10uL of labeled pentamer were added and incubated in room temperature (22–25°C) for 10 minutes. The samples were washed in 2mL of wash buffer and co-stained with anti-CD8 FITC-antibody for 20 minutes. Washed samples were subsequently used for FACS analysis (FACScalibur, BD Biosciences). FACS scattergrams were analyzed by first gating for size and CD8 expression on FL1 vs FSC dot plot and next by re-plotting CD8 positive cells on FL1 vs FL2 dot plot to assess percentage of CD8-pentamer double positive cells. Two separate assays were performed.

Statistics

All values are expressed as ± standard deviation and all experiments were repeated at least twice with comparable results. Differences between means were tested for significance by one-way ANOVA. Fisher’s exact test was used for proportions of animals surviving between two groups. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and a log-rank test. P-values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro experiments

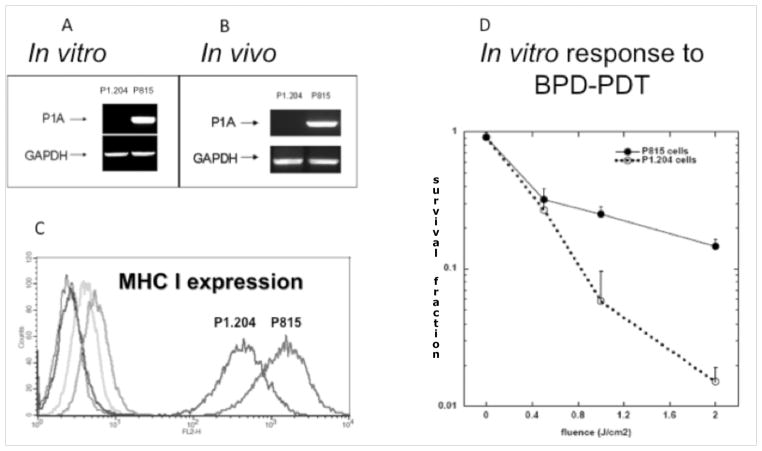

We employed a pair of previously described tumors that includes P1A antigen positive mouse mastocytoma P815 and a cell line derived from P815, P1A antigen negative P1.204. We measured the expression of P1A gene in both cell lines in vitro as well as ex vivo in tumors (Figure 1A&B) as well as the levels of MHC class I molecules (Figure 1C). Additionally, we compared the in vitro susceptibility to PDT (Figure 1D). The BPD mediated PDT was somewhat more effective against P1.204 cells most probably due to the fact that P1.204 cells grow as a suspension making them more susceptible to PDT treatment. Nevertheless, the result of this in vitro experiment suggests that the much better response seen in vivo to PDT of P815 tumors compared to the response seen with P1.204 tumors is not due to a possible inherent higher sensitivity of P815 cells to PDT. Rather the reverse is true, and P1.204 cells are inherently more sensitive to PDT.

Figure 1.

A. RT-PCR analysis of P1A expression in P1.204 and P815 cells. P815 cells show strong and constitutive expression of P1A antigen.

B. RT-PCR analysis of P1A expression in P1.204 and P815 tumors. P815 tumors show strong and constitutive expression of P1A antigen.

C. Histogram analysis of the levels of MHC I molecules in P815 and p1.204 cell lines. (Blue) P815 unstained control, (Dark Green) P815 Isotype control, (Red) P815 anti-MCH I, (Black) P.1204 unstained control, (Bright Green) P1.204 Isotype control, (Purple) P1.204 anti MHC I.

D. In vitro effectiveness of PDT against P815 and P1.204 cell lines.

PDT treatment is significantly more effective against P1A positive tumors

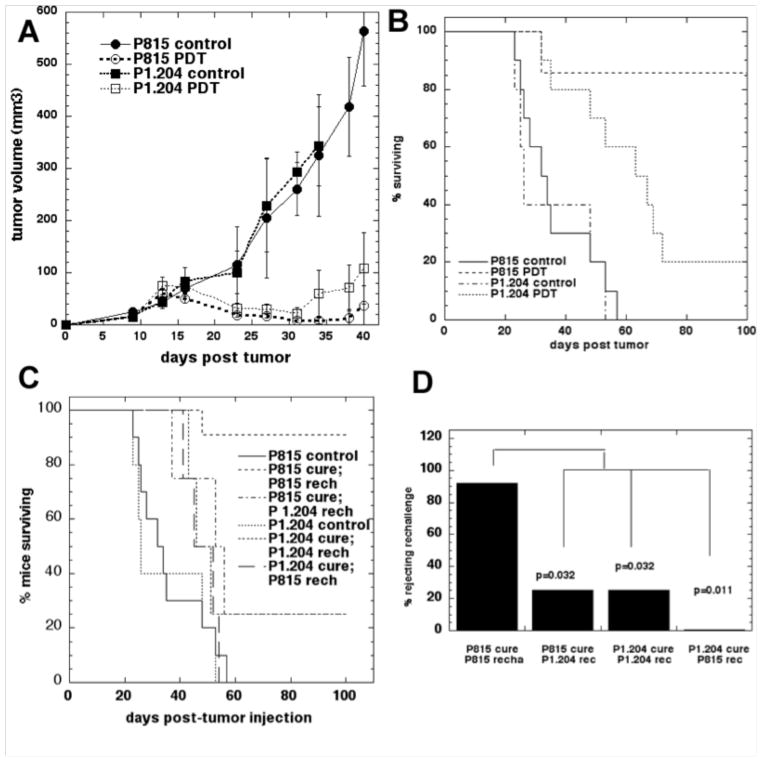

We employed a vascular PDT regimen delivered on day 9 after tumor inoculation in a set of in vivo experiments (Figure 2A). BPD-PDT led to a local response in both P1A antigen negative P1.204 tumors as well as in P1A antigen positive P815 tumors as manifested by a marked reduction in size lasting until day 32 (Figure 2A) and we were also able to induce long time survival (>90 days of observation) for mice bearing both varieties of tumors (Figure 2B). However, only in four out of 22 mice (18%) with P815 tumors treated with PDT, the local tumor recurred and regrew leading to sacrifice between days 44 and 57 after tumor injection. In contrast, 16 out of 21 mice (76%) with P1.204 tumors treated with PDT required sacrifice due to moribund state related to metastases or the local regrowth of the tumor. There were 18 cured mice in P815 PDT group compared to only five cured mice in P1.204 group (P<0.0001, Fisher exact test). Interestingly, in our in vivo studies we did not observe metastases of P815 tumors in immunocompetent control, or BPD-PDT treated mice. However we did see P815 tumors metastasizing in control nude and in nude BPD-PDT treated mice. These observations suggest that P815 tumors are intrinsically capable of metastasis, however it is strongly likely that in the immunocompetent mice the immune response prevents the metastases form occurring both in control and in PDT treated mice.

Figure 2.

A. Plots of mean tumor volumes in mice bearing control and PDT treated P815 tumors and P1.204 tumors. Points are means of from >20 tumors and bars are SD.

B. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the % of mice surviving over 90 days after PDT of P815 and P1.204 tumors. Control mice received no treatment. Median survival times were: P815 control tumors (40 days), P815 treated with PDT (not defined), P1.204 control tumors (37 days), P1.204 tumors treated with PDT (45 days). The significance values of the differences between the survival curves were as follows: P815 control vs P815 PDT (p<0.001); P815 control vs P1.204 control (p=0.56); P1.202 control vs P1.204 PDT (p=0.023); P815 PDT vs P1.204 PDT (p<0.001).

C. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the % of mice surviving the rechallenging studies in inducing memory immunity. Mice with P1A antigen positive P815 tumors that underwent PDT treatment and remained tumor free for 90 days were rechallenged with the same P1A antigen positive P815 tumor cells. The control groups (P815 and P1.204) were included to demonstrate viability of the tumor rechallenge.

D. Fisher exact test analysis of the proportion mice exhibiting successful rejection of rechallenge.

PDT induced memory immunity towards naturally occurring cancer testis antigen

To assess the generation of memory immunity we performed rechallenge experiments (Figure 2C&D). Mice bearing P1A antigen positive P815 tumors that had received PDT treatment and remained tumor free for 90 days were subsequently inoculated with the same P1A antigen positive P815 cells into the contralateral thigh; while PDT treated mice bearing P1A negative tumors P1.204 that survived tumor free for 90 days received P1.204 cells. 10 out of 11 mice (91%) rechallenged with P815 cells rejected the rechallenge with the identical tumor from which they were cured and survived tumor free for 60 days. However, only one mouse out of four mice (25%) rechallenged with P1.204 cells rejected the rechallenge with the identical tumor (P1.204) and survived over 60 days tumor free. To assess the tumor and antigen specificity of the observed memory immunity we performed cross-challenge studies. In this set of experiments mice cured of P1A antigen positive tumors P815 that survived tumor free for 90 days after PDT were inoculated with P1A antigen negative P1.204 cells and vice versa. One out of four mice rechallenged with the P1.204 tumors rejected the rechallenge and survived over 60 days while all tumors progressed when mice received P815 tumors.

Adaptive immune system is necessary for PDT anti-tumor effects

To corroborate our results indicating that PDT anti-tumor effects are indeed mediated by the activation of the immune system we repeated the experiments with P1A antigen positive P815 tumors in immunocompromised BALB/c Nu/Nu mice. PDT treatment produced a local response similar to that observed in immunocompetent DBA/2 mice; however, there was no survival advantage over non-treated controls and no permanent cures were observed (Figure 3A). The difference between PDT of P815 tumors in DBA2 mice and PDT in nude mice was highly significant (p<0.0001) and interestingly there was also a significant difference between survival of no treatment controls in nude and DBA2 mice (p-0.012). This observation shows that there is an immune response against P815 in untreated DBA2 mice that is insufficient to save any mice from death but does give a slower growth rate than in nude mice.

Figure 3.

A. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the % of BABL/c nude mice and DBA/2 mice surviving after PDT of P815 tumors. Control mice received no treatment. No significant difference between P815 and P815 PDT in nude mice. P815 in nude mice vs DBA2 mice (p=0.012). PDT of P815 in nude mice vs DBA2 mice (p<0.0001).

B. Mean volumes of P815 tumors growing in BALB/c Nu/Nu immunocompromised mice after adoptive transfer of lymph node cells from control non-treated or PDT treated DBA/2 mice bearing P815 tumors. The bars represent standard deviation.* p<0.05, **p<0.01

To provide additional evidence for the involvement of the immune system in anti-tumor PDT effects we also performed adoptive transfer experiments (Figure 3B). In this set of experiments we initially treated P815 tumors growing in immunocompetent DBA/2 mice with PDT and 5 days later we harvested the lymph node cells and transferred them i.v. into the immunocompromised BALB/c Nu/Nu. The control mice received lymph node cells from control, non-treated P815 bearing DBA/2 mice. Prior to lymph node cell transfer the immunocompromised BALB/c Nu/Nu in all experimental groups were inoculated with P815 tumors. The adoptive transfer significantly delayed the development and progress of P815 tumors and led to significant survival advantage.

These results provide strong evidence that the curative effects observed in case of P1A antigen positive P815 tumors were mediated by PDT activated, antigen specific and transferable immune response, and that the lack of functional adaptive immune system abrogates this effect.

PDT treatment leads to increase in intracellular production of cytokines in splenocytes from mice bearing antigen positive tumors

We compared to what extent the local PDT treatment of P1A antigen positive and negative tumors leads to activation of the immune system by measuring cytokines secreted in populations of CD4+ T cells. These experiments revealed that PDT treatment of P1A antigen positive P815 (but not P1A antigen-negative P1.204) tumors led to four-fold increase in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and more than three-fold in interleukin 2 (IL-2) levels (Figure 4) suggesting the active involvement of the Th1 arm of adaptive immune response. To further evaluate the PDT ability to activate T cells we measured and compared the levels of secreted cytokines by CD8+ T cells in control and PDT treated splenocytes from mice bearing P1A antigen positive P815 tumors. As can be seen in Figure 5A, PDT led to more than three-fold increase in the levels of both TNFα and IL2. These results strongly suggest that PDT of P1A antigen positive tumors leads to strong activation of Th1 arm of adaptive immune system as well as to activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.

Figure 4.

Intracellular levels of cytokines in CD4+ T cells isolated from control and PDT treated mice bearing P815 or P1.204 tumors.

Figure 5.

A. Intracellular levels of cytokines in CD8+ T cells isolated from control and PDT treated mice bearing P815 tumors.

B. Percentage of CD8+ T cells isolated from control and PDT treated mice bearing P1A antigen positive P815 tumors that are capable of recognizing LPYLGWLVF epitope from P1A antigen as shown by pentamer staining.

Pentamer staining reveals development of P1A epitope specific CD8+ T-cells after PDT

In order to establish that PDT can indeed lead to recognition of a specific peptide epitope derived from the tumor antigen P1A, we used pentamer staining. The lymph node cells isolated from control or PDT treated mice bearing P1A antigen positive P815 tumors were incubated with P1A epitope (LPYLGWLVF)-specific pentamer and co-stained for CD8 marker (Figure 5B). There was a significant difference (p<0.01) between binding of P1A pentamer by CD8 positive T cells isolated from control or PDT treated mice. These results strongly suggest that PDT does indeed induce recognition of MHC class I bound epitope derived from P1A antigen and provide additional evidence to support the notion that the expression of tumor antigen makes a significant difference in the final outcome of PDT of tumors.

DISCUSSION

The P815 tumor is perhaps the best-studied mouse tumor in the immunology and immunotherapy fields and the antigens expressed by P815 were the first mouse tumor antigens to be identified. However, there have been no studies reported with P815 tumors and PDT looking at the antigen specific immune response. We designed a study that used the mastocytoma P815 tumor cells syngeneic to DBA/2 mice that are expressing P1A (a MAGE-type mouse antigen) in parallel with P1.204 tumor cells (a P815 variant, negative for P1A) to investigate the effectiveness of PDT in this very clinically relevant setting. These tumor cells have been widely used in murine tumor immunologic response studies (40–42) and at least four distinct antigens (P815: AB, C, D, E) characterized by five epitopes (P1A, P1B, P1C, P1D, and P1E), capable of inducing CTL response, have been identified; with the main component of the CTL response against the P815 tumor being targeted against P815AB and P815E (43). The P815 antigen shares many characteristics found in human TAA genes (particularly those belonging to the MAGE family in melanomas and other tumors) (44), and these antigens are not expressed in most adult tissues, with the exception of testis and placenta (37). The P1.204 is a cell line derived from an immune system escape variant of P815 (42) that has lost the P815AB antigen but retains the P815E antigen. The response to PDT (of both tumors) is consistent with these factors.

We found that the two tumors had differences that were manifest in how the cells grew in vitro. P815 cells grew as adherent monolayers while P1.204 cells grew as suspensions. This difference in the in vitro growth pattern probably accounted for differences that we found in the susceptibility of the two lines to PDT with liposomal BPD as well. As it happens, the suspension P1.204 cells were more susceptible to PDT than the adherent P815 cells, and this meant that the greater response to PDT we observed of P815 tumors in mice could not be attributed to an inherently greater susceptibility of the tumor cells (rather the reverse). The initial reaction of both tumor types to PDT was similar with a black eschar developing at the site of the tumor and accompanied by marked tumor shrinkage. The subsequent course of the mice however was very different. The majority of the mice with PDT-treated P815 tumors demonstrated a regression and continued absence of the tumor that lasted up to 90 days of observation. The remaining 4 out of 22 mice demonstrated a local recurrence of the tumor leading to sacrifice due to progressive growth between days 44 and 57. On the other hand, the 21 mice with PDT-treated P1.204 tumors did not fare as well. The first mouse needed to be sacrificed due to metastatic disease at day 31 and this continued to be necessary at intervals until only 5 out of 21 remained alive and healthy at day 66. The difference in response between the two tumor types was hypothesized to be due to immune response, especially as P1.204 cells were more susceptible to PDT.

To confirm the involvement of the mouse immune system in the long-term response to PDT in these models, we rechallenged the cured mice with the identical tumor from which they were originally cured. Only mice cured from P1A antigen positive P815 tumors reliably rejected the rechallenge while 100% of the naïve mice injected with either cell line grew tumors. This observation implies that in case of P1A antigen positive P815 tumors a strong immunity developed after PDT sufficient to prevent tumor growth when a tumorigenic dose of cells was re-injected.

The P815 cell line (apart from P1A) expresses additional known antigens such as P1B and P1E, and presumably, the T-cells that arise after PDT could recognize either P815AB or P815E epitopes. If this were the case then mice cured of P815 tumor could also be capable of rejecting a challenge with P1.204 tumors. Our hypothesis proved to be correct only in a limited number of mice as seen in the cross-challenge study. The phenomenon of P815 tumors escaping a successful initial immune response is well documented (42, 45–47). For the P1A peptide antigen LPYLGWLVF expressed in P185 progression was reported to occur due to antigenic loss (48).

In the ex vivo set of studies we asked the question to what extent does PDT of P815 mastocytoma induce host anti-tumor immune response and whether P1A antigen is recognized by T-cells before and after PDT. Brichard et al showed (49) that T-cells isolated from DBA/2 mice bearing growing P815 tumors primarily recognized either antigens AB or CDE, but not both. We measured therefore the levels of cytokines secreted by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to compare the effects of PDT treatment and we showed that PDT of P1A antigen positive tumors led to marked increase in levels of TNFα and IL-2. Additionally, we were able to identify a population of CD8+ T cells able to effectively recognize a LPYLGWLVF epitope from P1A antigen. Lastly we were able to show that the lack of an adaptive immune system in nude mice could completely abrogate the anti-tumor effectiveness of PDT in mice bearing P1A antigen positive P815 tumors. Moreover survival of nude mice with P815 tumors could be significantly prolonged by adoptive transfer of activated lymph node cells isolated from immunocompetent mice with PDT-treated P815 tumors.

Our findings presented here are in accordance with a study published by Kabingu et al. (50) as well as our paper (34) where we demonstrated for the first time that PDT can lead to the development of systemic, antigen specific immune response towards tumors expressing the model tumor antigen β-galactosidase. The results derived from our current study, however, may have direct translation regarding the PDT application in clinical cancer therapy. Firstly, if a tumor antigen is constitutively expressed in tumor tissues, PDT may be ultimately more successful in the patient population with tumors positive for that particular antigen. Secondly, although PDT of cells in vitro has been shown to generate anti-cancer vaccines that are superior to other cytotoxic strategies (51), the role of tumor antigens has never been addressed in this setting. Thirdly, even though many solid tumors show heterogeneous expression of tumor antigens, recent data suggest that de novo induction of tumor antigens in solid tumors may represent a novel means to break tumor escape mechanisms (52). Fourthly, the combination of PDT with various strategies that enhance the expression of tumor antigens and their presentation by MHC I molecules, may extend the benefits of this therapy to those cancers that are otherwise untreatable.

Collectively, the data presented in this study employing tumors expressing clinically relevant, naturally occurring tumor antigen P1A, a murine homologue of cancer testis antigen, provide additional, strong evidence that the antigen expression in PDT treated tumors leads to better treatment outcomes and should be considered as a positive factor in patient prognosis and clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to QLT Inc (Vancouver, Canada) for the generous gift of BPD and to ProImmune for a generous gift of P1A pentamer. We are grateful to Dr. Thomas Gajewski from Department of Pathology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL for providing P815 and P1.204 cell lines.

Grant support. US NIH (grants RO1CA/AI838801 and R01AI050875 to MRH). P.M. was partly supported by Genzyme-Partners Translational Research Grant and NIH Dermatology Training Grant. A.M. was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science, International Union Against Cancer and European Structural Fund: “Mazowieckie Stypendium Doktoranckie”.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2011 doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:535–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolmans DE, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cecic I, Korbelik M. Mediators of peripheral blood neutrophilia induced by photodynamic therapy of solid tumors. Cancer Lett. 2002;183:43–51. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg AD, Krysko DV, Vandenabeele P, Agostinis P. DAMPs and PDT-mediated photo-oxidative stress: exploring the unknown. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10:670–80. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korbelik M, Cecic I, Merchant S, Sun J. Acute phase response induction by cancer treatment with photodynamic therapy. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1411–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krosl G, Korbelik M, Dougherty GJ. Induction of immune cell infiltration into murine SCCVII tumour by photofrin-based photodynamic therapy. BrJCancer. 1995;71:549–55. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecic I, Stott B, Korbelik M. Acute phase response-associated systemic neutrophil mobilization in mice bearing tumors treated by photodynamic therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korbelik M, Cecic I. Complement activation cascade and its regulation: relevance for the response of solid tumors to photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2008;93:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecic I, Serrano K, Gyongyossy-Issa M, Korbelik M. Characteristics of complement activation in mice bearing Lewis lung carcinomas treated by photodynamic therapy. Cancer Lett. 2005;225:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cecic I, Korbelik M. Deposition of complement proteins on cells treated by photodynamic therapy in vitro. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25:189–203. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v25.i1-2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecic I, Sun J, Korbelik M. Role of complement anaphylatoxin C3a in photodynamic therapy-elicited engagement of host neutrophils and other immune cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:558–62. doi: 10.1562/2005-09-09-RA-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stott B, Korbelik M. Activation of complement C3, C5, and C9 genes in tumors treated by photodynamic therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:649–58. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0221-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Bruggen P, Van den Eynde BJ. Processing and presentation of tumor antigens and vaccination strategies. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. T cell defined tumor antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:684–93. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Inoda S, Kobayasi J, Nakatsugawa M, Mori T, et al. The functioning antigens: beyond just as the immunological targets. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:798–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Bode B, Wenger RH, Lehmann K, Sartori AA, Moch H, et al. gamma-Radiation promotes immunological recognition of cancer cells through increased expression of cancer-testis antigens in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith HA, McNeel DG. The SSX family of cancer-testis antigens as target proteins for tumor therapy. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:150591. doi: 10.1155/2010/150591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Wolfel C, De Plaen E, Lethe B, et al. The tyrosinase gene codes for an antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1993;178:489–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulie PG, Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Schneider J, Traversari C, et al. A new gene coding for a differentiation antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1994;180:35–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakker AB, Schreurs MW, de Boer AJ, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA, Adema GJ, et al. Melanocyte lineage-specific antigen gp100 is recognized by melanoma-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1005–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulie PG, Lehmann F, Lethe B, Herman J, Lurquin C, Andrawiss M, et al. A mutated intron sequence codes for an antigenic peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7976–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandelboim O, Berke G, Fridkin M, Feldman M, Eisenstein M, Eisenbach L. CTL induction by a tumour-associated antigen octapeptide derived from a murine lung carcinoma. Nature. 1994;369:67–71. doi: 10.1038/369067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monach PA, Meredith SC, Siegel CT, Schreiber H. A unique tumor antigen produced by a single amino acid substitution. Immunity. 1995;2:45–59. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Kawakami Y, Loftus D, Appella E, et al. A mutated beta-catenin gene encodes a melanoma-specific antigen recognized by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1185–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubey P, Hendrickson RC, Meredith SC, Siegel CT, Shabanowitz J, Skipper JC, et al. The immunodominant antigen of an ultraviolet-induced regressor tumor is generated by a somatic point mutation in the DEAD box helicase p68. J Exp Med. 1997;185:695–705. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laheru D, Jaffee EM. Immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer - science driving clinical progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:459–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall JL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Beetham PK, Tsang KY, Slack R, et al. Phase I study of sequential vaccinations with fowlpox-CEA(6D)-TRICOM alone and sequentially with vaccinia-CEA(6D)-TRICOM, with and without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, in patients with carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:720–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Bronte V, Chen PW, Gritz L, Panicali D, Rosenberg SA, et al. Active immunotherapy of cancer with a nonreplicating recombinant fowlpox virus encoding a model tumor-associated antigen. J Immunol. 1995;154:4685–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe BJ, Irvine KR, Nishimura MI, Yang JC, Spiess PJ, Shulman EP, et al. Minimal determinant expressed by a recombinant vaccinia virus elicits therapeutic antitumor cytolytic T lymphocyte responses. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1741–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzo AL, Lake RA, Robinson BW, Scott B. T-cell receptor transgenic analysis of tumor-specific CD8 and CD4 responses in the eradication of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1071–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castano AP, Liu Q, Hamblin MR. A green fluorescent protein-expressing murine tumour but not its wild-type counterpart is cured by photodynamic therapy. Br J Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mroz P, Szokalska A, Wu MX, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy of tumors can lead to development of systemic antigen-specific immune response. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van den Eynde B, Lethe B, Van Pel A, De Plaen E, Boon T. The gene coding for a major tumor rejection antigen of tumor P815 is identical to the normal gene of syngeneic DBA/2 mice. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1373–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramarathinam L, Sarma S, Maric M, Zhao M, Yang G, Chen L, et al. Multiple lineages of tumors express a common tumor antigen, P1A, but they are not cross-protected. J Immunol. 1995;155:5323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyttenhove C, Godfraind C, Lethe B, Amar-Costesec A, Renauld JC, Gajewski TF, et al. The expression of mouse gene P1A in testis does not prevent safe induction of cytolytic T cells against a P1A-encoded tumor antigen. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:349–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970127)70:3<349::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiriva-Internati M, Pandey A, Saba R, Kim M, Saadeh C, Lukman T, et al. Cancer testis antigens: a novel target in lung cancer. Int Rev Immunol. 2012;31:321–43. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.723512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandey A, Kurup A, Shrivastava A, Radhi S, Nguyen DD, Arentz C, et al. Cancer testes antigens in breast cancer: biological role, regulation, and therapeutic applicability. Int Rev Immunol. 2012;31:302–20. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.723511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lethe B, van den Eynde B, van Pel A, Corradin G, Boon T. Mouse tumor rejection antigens P815A and P815B: two epitopes carried by a single peptide. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2283–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ni B, Lin Z, Zhou L, Wang L, Jia Z, Zhou W, et al. Induction of P815 tumor immunity by DNA-based recombinant Semliki Forest virus or replicon DNA expressing the P1A gene. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uyttenhove C, Maryanski J, Boon T. Escape of mouse mastocytoma P815 after nearly complete rejection is due to antigen-loss variants rather than immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1040–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.3.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bilsborough J, Van Pel A, Uyttenhove C, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. Identification of a second major tumor-specific antigen recognized by CTLs on mouse mastocytoma P815. J Immunol. 1999;162:3534–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandle D, Bilsborough J, Rulicke T, Uyttenhove C, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. The shared tumor-specific antigen encoded by mouse gene P1A is a target not only for cytolytic T lymphocytes but also for tumor rejection. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4010–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4010::AID-IMMU4010>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen PW, Uno T, Ksander BR. Tumor escape mutants develop within an immune-privileged environment in the absence of T cell selection. J Immunol. 2006;177:162–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12293–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maryanski JL, Marchand M, Uyttenhove C, Boon T. Immunogenic variants obtained by mutagenesis of mouse mastocytoma P815. VI. Occasional escape from host rejection due to antigen-loss secondary variants. Int J Cancer. 1983;31:119–23. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bai XF, Liu JQ, Joshi PS, Wang L, Yin L, Labanowska J, et al. Different Lineages of P1A-Expressing Cancer Cells Use Divergent Modes of Immune Evasion for T-Cell Adoptive Therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8241–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brichard VG, Warnier G, Van Pel A, Morlighem G, Lucas S, Boon T. Individual differences in the orientation of the cytolytic T cell response against mouse tumor P815. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:664–71. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabingu E, Oseroff AR, Wilding GE, Gollnick SO. Enhanced systemic immune reactivity to a Basal cell carcinoma associated antigen following photodynamic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4460–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA Cancer J Clin. 61:250–81. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo ZS, Hong JA, Irvine KR, Chen GA, Spiess PJ, Liu Y, et al. De novo induction of a cancer/testis antigen by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine augments adoptive immunotherapy in a murine tumor model. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1105–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]