Abstract

Background and Purpose

Retigabine is a recently approved antiepileptic agent which activates Kv7.2–7.5 potassium channels. It is emerging that these channels have an important role in vascular regulation, but the vascular effects of retigabine in the conscious state are unknown. Hence, in the present study we assessed the regional haemodynamic responses to retigabine in conscious rats.

Experimental Approach

Male Sprague Dawley rats were chronically instrumented with pulsed Doppler flow probes to measure regional haemodynamic responses to retigabine under control conditions and during acute hypertension induced by infusion of angiotensin II and arginine vasopressin. Further experiments were performed, using the β-adrenoceptor antagonists CGP 20712A, ICI 118551 and propranolol, to elucidate the roles of β-adrenoceptors in the responses to retigabine in vivo and in vitro.

Key Results

Under normotensive conditions, retigabine induced dose-dependent hypotension and hindquarters vasodilatation, with small, transient renal and mesenteric vasodilatations. In the acutely hypertensive state, the renal and mesenteric, but not hindquarters, vasodilatations were enhanced. The response of the hindquarters vascular bed to retigabine was mediated, in part, by β2-adrenoceptors. However, in vitro experiments confirmed that retigabine did not act as a β-adrenoceptor agonist.

Conclusions and Implications

We demonstrated that retigabine causes regionally specific vasodilatations, which are different under normotensive and hypertensive conditions, and are, in part, mediated by β2-adrenoceptors in some vascular beds but not in others. These results broadly support previous findings and further indicate that Kv7 channels are a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of vascular diseases associated with inappropriate vasoconstriction.

Keywords: retigabine, Kv7, KCNQ, hypertension, β-adrenoceptors, haemodynamic responses, conscious rats

Introduction

Voltage-dependent potassium (K+) channels have a well-established role in the determination and stabilization of the resting membrane potential and electrical excitability in many cell types, including neurons, cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (Iannotti et al., 2010; Jepps et al., 2011). The KCNQ1-5 gene encodes the Kv7 family of K+ channels, which comprises the Kv7.1-7.5 subtypes, each with distinct localization and physiological function (for review, see Brown and Passmore, 2009). Impaired activation of Kv7 channels is associated with a number of pathophysiological conditions, including hypertension, neuropathic pain and epilepsy (Goto et al., 2001; Su et al., 2011).

Modulators of K+ channels, including linopirdine and retigabine (ezogabine), have recently been developed to antagonize and activate these channels, respectively. Linopirdine was developed as a cognition enhancer for treatment of neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease; however, serious cholinergic hyperstimulation and pro-epileptic side effects have limited its clinical use (Miceli et al., 2012). In 2011, retigabine, a selective Kv7 channel activator, received European approval for use as an adjunctive treatment of partial-onset epileptic seizures in adults (European Medicines Agency, 2011; Stafstrom et al., 2011; Martyn-St James et al., 2012). Retigabine is now considered a first-in-class novel antiepileptic agent with proven efficacy for seizure control and as an anticonvulsant (Ferron et al., 2002; Su et al., 2011; Brickel et al., 2012; Ciliberto et al., 2012). The pharmacological actions of retigabine include positive allosteric modulation of Kv7.2–7.5, but not Kv7.1, channels (Main et al., 2000; Rundfeldt and Netzer, 2000; Wickenden et al., 2000), culminating in increased K+ conductance, a shift in voltage-dependent channel activation to more hyperpolarized potentials, and a reduction in cell excitability (Main et al., 2000; Rundfeldt and Netzer, 2000; Wickenden et al., 2000; Otto et al., 2002; Gunthorpe et al., 2012).

As recently reviewed by Jepps et al. (2013), there is increased recognition of the importance of Kv7 channels in controlling smooth muscle activity. Thus, in addition to the well-described antiepileptic effects of retigabine, Kv7 channel modulators also affect a variety of smooth muscle functions including cardiovascular regulation. Indeed, adverse dose-limiting cardiovascular effects such as symptomatic hypotension, prolongation of the QTc interval and arrhythmias have been reported in healthy volunteers (Ferron et al., 2002), and in patient populations (EMA, 2011; reviewed by Jepps et al., 2013). Recent functional studies have shown that Kv7 channel activators have vasorelaxant effects in rat precontracted, isolated blood vessels (Chadha et al., 2012a), and that Kv7 channels are involved in β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasorelaxation responses (Chadha et al., 2012b). Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that the vasoconstrictor effect of arginine vasopressin (AVP) may be mediated, in part, by inhibition of Kv7 channels (Brueggemann et al., 2007; Mackie et al., 2008). Collectively, these findings suggest that Kv7 channel activators have the potential to be used as antihypertensive agents (Ng et al., 2011), although Kv7 channel function has been found to be impaired in several models of hypertension (Morecroft et al., 2009; Jepps et al., 2011; Chadha et al., 2012b).

The recent review by Jepps et al. (2013) provided evidence to support the contention that ‘Kv7 channels are vital determinants of resting vascular tone’ but to date, there have been very few in vivo studies in which the cardiovascular effects of Kv7 channel activation have been investigated and, to our knowledge, none in which the regional haemodynamic effects have been monitored in conscious animals. Therefore, the main aim of the present study was to determine the regional haemodynamic effects of retigabine, administered i.v., in normotensive and hypertensive, conscious rats. The results of the initial studies showed that retigabine induced vasodilator effects that had different time-courses in the various vascular beds investigated. Specifically, in the hindquarters the vasodilatation in response to retigabine was considerably more prolonged than that in the renal and mesenteric vascular beds. Since previous experiments in this experimental model have shown that long-lasting hindquarters vasodilatation is a hallmark of β-adrenoceptor-mediated stimulation (e.g. Gardiner et al., 2010), additional studies were performed to determine whether the activation of β-adrenoceptors is involved in any of the vasodilator effects of retigabine. Hence, we performed additional in vitro experiments to address the possibility that the vasodilator responses to retigabine mediated by β-adrenoceptors are as a result of a direct effect of this drug on these receptors. We demonstrated that retigabine causes regionally specific vasodilatations, which are different under normotensive and hypertensive conditions, and are, in part, mediated by β2-adrenoceptors in some vascular beds but not in others.

Methods

In vivo studies

All procedures were approved by the University of Nottingham Ethical Review Committee and were carried out under Home Office Project and Personal Licence authority. Every effort was made to ensure that animals experienced minimal discomfort. Twenty-seven rats were used for this study, and results are recorded in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (McGrath et al., 2010).

Animals and surgical preparation

Male, Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, Margate, UK), weighing 300–350 g, were group-housed in individually ventilated cages in a temperature-controlled (21–23°C) environment with a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0600 h), and free access to food (18% Protein Rodent Diet; Teklad Global, Bicester, UK) and water for at least 7 days after arrival from the supplier before any surgical intervention. Daily welfare checks were carried out.

Surgery was performed in two stages under general anaesthesia (fentanyl and medetomidine, 300 μg·kg−1 i.p. of each, supplemented as required), with reversal of anaesthesia and postoperative analgesia provided by atipamezole (1 mg·kg−1 s.c.) and buprenorphine (0.02 mg·kg−1 s.c.). Depth of anaesthesia was assessed by monitoring paw pinch withdrawal. At the first stage, miniature pulsed Doppler flow probes were sutured around the superior mesenteric artery, the left renal artery and the distal abdominal aorta (to monitor hindquarters flow). The wires from the probes were tunnelled s.c. and secured at the back of the neck. Anaesthesia was then reversed and a postoperative analgesic administered (see above), and the animals were placed in individual cages on heat mats to recover. At the end of the day, animals were returned to the holding room, and then re-housed in pairs the following morning. The second stage of surgery took place at least 10 days after probe implantation, following a satisfactory welfare check from the Named Veterinary Surgeon. Under anaesthesia (as above), catheters were implanted into the distal abdominal aorta, via the caudal artery, for monitoring mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate, and the right jugular vein (three i.v. catheters for concurrent administration of substances). At this stage, the wires from the probes were soldered into a miniature plug (Microtech, Boothwyn, PA, USA) attached to a custom-designed harness worn by the rat. The wires and catheters emerged from the rat at the same point, and were fed through a protective spring and attached to a counter-balanced pivot system. The arterial catheter was connected to a fluid-filled swivel for overnight infusion of saline containing heparin (15 U·mL−1, 0.4 mL·h−1) to maintain patency. Post-surgery, animals were singly housed in experimental cages.

Cardiovascular recordings began 24 h after catheterization, when animals were fully conscious and freely moving, with free access to water and food. Drugs were administered i.v., through the previously implanted catheters, to minimize disruption to the animals during the experiments and allow measurement of the effects immediately after dosing.

Cardiovascular recordings

Continuous recordings of cardiovascular variables [including heart rate, BP, renal, mesenteric and hindquarters Doppler shifts (flows)] were made using a customized, computer-based system [Instrument Development Engineering Evaluation (IDEEQ), Maastricht Instruments Bv, Maastricht, The Netherlands] connected to a transducer amplifier (model 13-4615-50; Gould, Eastlake, OH, USA) and a Doppler flowmeter (Crystal Biotech, Holliston, MA, USA) VF-1 mainframe (pulse repetition frequency 125 kHz) fitted with high-velocity (HVPD-20) modules]. Raw data were sampled by IDEEQ every 2 ms, averaged and stored to disc every cardiac cycle. Changes in vascular conductance were calculated from the changes in BP and Doppler shift.

Experimental protocol

Experiment 1: Cardiovascular responses to retigabine under normotensive and hypertensive conditions

The aim of this experiment was to measure the cardiovascular responses to Kv7 channel activation by retigabine, under normotensive conditions and during acute hypertension, induced by the combined administration of angiotensin II (AII) plus AVP, as described previously (Ho and Gardiner, 2009).

Two groups of animals (n = 8 and n = 7) were used for this experiment, which ran over 3 days. On the first day, animals received an infusion (0.4 mL·h−1) of saline (Group 1; n = 8), or AII-AVP (0.1 μg·kg−1·h−1 and 0.01 μg·kg−1·h−1, respectively; Group 2; n = 7). At least 90 min later, three bolus doses (0.1 mL) of retigabine (1 mg·kg−1; 3 mg·kg−1; 5 mg·kg−1) or vehicle (saline) were administered to each rat over 5 s, at least 1 h apart. These doses of retigabine have been used previously in conscious rats (Streng et al., 2004). At least 1 h later, recordings were stopped and animals were re-attached to the fluid-filled swivels. On the second day, no drugs were administered and the arterial catheters were routinely flushed with heparinized saline (30 U·mL−1) to maintain patency. On the final day, animals were again infused with saline (Group 1) or AII-AVP (Group 2), as above, and those which were given retigabine on day 1 were given vehicle and vice versa. Animals were allocated to each group in a randomized order, and this design allowed each animal to act as its own control.

Due to transient behavioural effects triggered by 5 mg·kg−1 retigabine in some animals (3 out of 15), 3 mg·kg−1 was chosen as the dose for further experiments.

Experiment 2: Responses to retigabine in the presence of β-adrenoceptor antagonism

The aim of this experiment was to elucidate the role of β-adrenoceptors in the responses to retigabine. Two groups of animals were used, and the experiments ran contemporaneously.

The effects of the non-selective β-adrenoceptor antagonist, propranolol

One group of animals (n = 6) received a primed infusion (0.1 mL, 0.4 mL·h−1) of propranolol (1 mg·kg−1 bolus, 0.5 mg kg−1 h−1 infusion) or saline on the first day. At least 90 min later, a bolus dose (0.1 mL) of retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) was administered over 5 s. At least 1 h later, recordings were stopped and animals were re-attached to the fluid-filled swivels. On the second day, no drugs were administered and the arterial catheters were routinely flushed with heparinized saline (30 U·mL−1) to maintain patency. On the final day, animals which were given propranolol on day 1 were given saline and vice versa. Due to a technical failure, the retigabine/saline data from one animal was not included in the analysis.

The effects of selective β1- or β2-adrenoceptor antagonism

One group of animals (n = 6) was used for this experiment, which lasted 3 days. On the first day, animals received a bolus dose (0.1 mL) of retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) at least 90 min after the start of a primed infusion of the β1-adrenoceptor antagonist, CGP 20712A, or the β2-adrenoceptor antagonist, ICI 118551 (both at 200 μg·kg−1 bolus, 100 μg·kg−1·h−1 infusion). No drugs were administered on the second day. On the final day, animals which were given CGP 20712A on day 1 were given ICI 118551, and vice versa, as described above. Previously, we have shown that these doses are selective for the appropriate receptor (Baker et al., 2011), and do not affect cardiovascular responses 24 h post-administration (Fretwell and Woolard, unpubl. data), thus we were confident that drugs given on the first day would not affect subsequent treatments.

Experiment 3: In vitro studies

These data were kindly provided by Richard Proudman and Jillian Baker. In order to determine whether retigabine was directly interacting with β-adrenoceptors, the ability of retigabine to interact with β1- and β2-adrenoceptors stably expressed in CHO cell lines was examined using both a [3H]-CGP 12177 whole cell binding assay and a functional CRE-SPAP (secreted placental alkaline phosphate) production assay, as described previously (Baker, 2005, and Baker, 2010, respectively). Although these CHO cell lines stably express the human β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, ligand affinity and efficacy has previously proved to be highly predictive of that seen in the in vivo rat model (Baker et al., 2011).

In vivo data analysis

Data were analysed offline using IDEEQ software (University of Maastricht, The Netherlands). For all experiments, time-averaged data are shown as changes from baseline [HR (beats·min−1); BP (mmHg); vascular conductances (%)]. Statistical comparisons between effects of different doses of retigabine, or between effects of retigabine under different conditions, were performed on the integrated changes over specified time periods. As the data were not all normally distributed, a non-parametric, repeated-measures analysis of variance (Friedman's test; Theodorsson-Norheim, 1987) was used for within-group comparisons, and Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis for between-group comparisons, as appropriate. Vascular conductances were calculated from the BP and Doppler shift (flow) data. P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Each animal represented one experimental unit.

Materials

Retigabine dihydrochloride was from Sequoia Research Products (Pangbourne, UK). AII, AVP and CGP 20712A were from Tocris Biosciences (via R&D Systems Europe Ltd., Abingdon, UK). Propranolol [(RS)-1-[(1-methylethyl)amino]-3-(1-naphthalenyloxy)-2-propanol hydrochloride], ICI 118551 and atropine methyl nitrate were from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK).

Stock solutions of AII and AVP were made up in sterile distilled water. All drugs were dissolved in sterile saline for in vivo administration. Bolus doses were given in 0.1 mL and infusions were at 0.4 mL·h−1.

Drugs and molecular target nomenclature conform to the British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

Experiment 1: Cardiovascular responses to retigabine under normotensive and hypertensive conditions

Baseline cardiovascular variables before the administration of retigabine are shown in Table 1, and integrated (area under/over curves, 0–30 min) cardiovascular responses to retigabine are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Resting cardiovascular variables obtained before the administration of the first dose of retigabine in animals pretreated with either saline (n = 8) or AII plus AVP (n = 7)

| Pretreatment | Saline (n = 8) | AII + AVP (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| HR (beats·min−1) | 324 ± 8 | 332 ± 14 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 101 ± 4 | 141 ± 6* |

| RVC (U) | 75 ± 11 | 45 ± 7* |

| MVC (U) | 54 ± 15 | 39 ± 7* |

| HVC (U) | 44 ± 5 | 36 ± 5* |

Units for VC are (kHz·mmHg−1)103.

Values are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 versus saline group (Mann–Whitney test) (Experiment 1).

AII, angiotensin II; AVP, arginine vasopressin; H, hindquarters; HR, heart rate; M, mesenteric; MAP, mean arterial pressure; R, renal; U, units; VC, vascular conductance.

Table 2.

Integrated (0–30 min) changes in cardiovascular variables following administration of retigabine in animals pretreated with saline (n = 8) or AII plus AVP (n = 7)

| Retigabine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mg·kg−1 | 3 mg·kg−1 | 5 mg·kg−1 | |

| Saline (n = 8) | |||

| HR (AOC, beats) | +211 ± 112 | +549 ± 202 | +1108 ± 510 |

| HR (AUC, beats) | −84 ± 38 | −207 ± 92 | −159 ± 89 |

| MAP (mmHg min) | −70 ± 12 | −216 ± 62 | −383 ± 1191 |

| RVC (% min) | +105 ± 41 | +138 ± 53 | +260 ± 104 |

| MVC (% min) | +218 ± 79 | +145 ± 62 | +219 ± 87 |

| HVC (% min) | +216 ± 53 | +801 ± 2781 | +1614 ± 31813 |

| AII-AVP (n = 7) | |||

| HR (AOC, beats) | +256 ± 132 | +617 ± 143 | +1197 ± 438 |

| HR (AUC, beats) | −535 ± 220* | −177 ± 80 | −168 ± 124 |

| MAP (mmHg min) | −104 ± 47 | −335 ± 81 | −807 ± 144* |

| RVC (% min) | +33 ± 15 | +312 ± 110 | +1137 ± 210* |

| MVC (% min) | +191 ± 95 | +408 ± 117* | +1009 ± 181* |

| HVC (% min) | +168 ± 77 | +758 ± 104 | +1548 ± 384 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. 1 mg·kg−1,

3P < 0.05 vs. 3 mg·kg−1 (Friedman's test).

P < 0.05 vs. saline group (Mann–Whitney test). For other abbreviations see Table 1 (Experiment 1).

AOC, area over the curve; AUC, area under the curve.

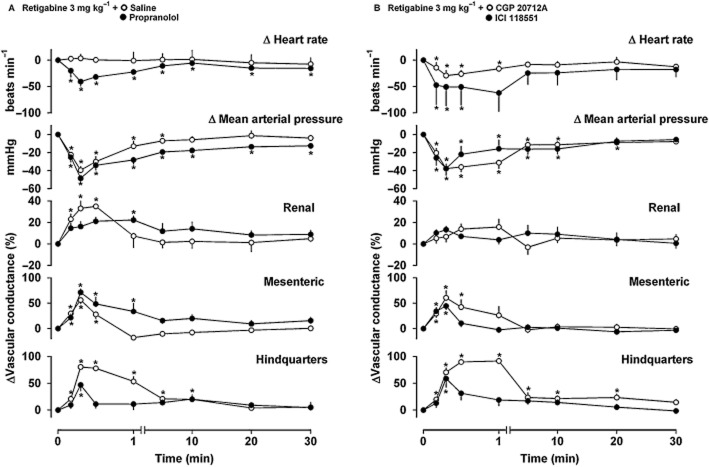

Normotensive conditions

Administration of vehicle (saline) in the presence of saline had no cardiovascular effects (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular responses to retigabine (1 mg·kg−1, 3 mg·kg−1 or 5 mg·kg−1, n = 8) and vehicle (saline, n = 8) following pretreatment with saline. Data points are mean and vertical bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05 versus baseline (Friedman's test). Note that a non-linear time scale is used for the initial 1 min to illustrate the rapid and transient haemodynamic effects of retigabine (Experiment 1).

The low dose of retigabine (1 mg·kg−1) produced no significant haemodynamic effects other than a slight hindquarters vasodilatation (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 1 min). At 3 mg·kg−1, retigabine caused a transient fall in BP (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 20–60 s), accompanied by small, short-lived renal and mesenteric vasodilatations (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 20 s) and a more prolonged hindquarters vasodilatation (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s–10 min). The highest dose of retigabine (5 mg·kg−1) caused a fall in BP (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s–20 min), with transient renal and mesenteric vasodilatations (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10–60 s and 10–30 s, respectively), and a prolonged hindquarters vasodilatation (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s–30 min). The integrated (0–30 min) hypotensive and hindquarters vasodilator effects of retigabine were dose-dependent (Table 2).

Heart rate responses to retigabine were very variable, particularly at the lower doses, with some animals showing predominantly tachycardia and others showing bradycardia, hence integrated responses are given for both areas under and over the curves (Table 2).

Hypertensive conditions

The pressor effect of AII-AVP infusion was accompanied by reduced renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular conductances (P < 0.05 vs. saline group; Table 1). In the presence of AII-AVP (Figure 2), at the low dose (1 mg·kg−1), retigabine caused a slight fall in blood pressure (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10–20 s), with small renal and mesenteric vasodilatations (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s and 10–20 s, respectively). There was no significant change in hindquarters vascular conductance. At 3 mg·kg−1, retigabine caused a more prolonged fall in BP (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s–30 min), accompanied by transient renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vasodilatations (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 20–60 s, 20–30 s and 20 s–10 min, respectively). At the highest dose (5 mg·kg−1), retigabine caused a fall in BP (P < 0.05 vs. baseline at 10 s–30 min) and prolonged vasodilatations in all three vascular beds [P < 0.05 vs. baseline at (renal) 10 s–30 min, (mesenteric) 10 s–10 min and (hindquarters) 10 s–30 min]. As before, the heart rate responses to retigabine were very variable.

Figure 2.

Haemodynamic effects of retigabine (1 mg·kg−1, 3 mg·kg−1 and 5 mg·kg−1, n = 7) and vehicle (saline, n = 7) in conscious, AII-AVP-treated rats. Data points are mean and vertical bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05 versus baseline (Friedman's test). Between-group differences are given in the text. AII-AVP, angiotensin II and arginine vasopressin (Experiment 1).

Comparison between normotensive and hypertensive conditions

Under hypertensive conditions, the hypotensive and renal and mesenteric vasodilator effects of the highest dose of retigabine (5 mg·kg−1) were significantly enhanced (P < 0.05 vs. saline group). Renal and mesenteric vasodilator effects of 3 mg·kg−1 retigabine also tended to be enhanced in the hypertensive condition, but the effect was only significant (P < 0.05) for the mesenteric vasodilatation (P = 0.08 for renal vasodilator response vs. saline).

Experiment 2: Responses to retigabine in the presence of β-adrenoceptor antagonism

There were no statistically significant differences between resting cardiovascular variables following administration of saline, propranolol, CGP 20712A or ICI 118551 (Table 3); integrated (0–30 min) cardiovascular responses to retigabine are given in Table 4.

Table 3.

Resting cardiovascular variables obtained before the administration of retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) or vehicle

| Pretreatment | Saline (n = 5) | Propranolol (n = 6) | CGP 20712A (n = 6) | ICI 118551 (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (beats·min−1) | 340 ± 9 | 322 ± 6 | 326 ± 8 | 353 ± 15 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 100 ± 2 | 107 ± 2 | 100 ± 2 | 110 ± 3 |

| RVC (U) | 84 ± 4 | 82 ± 7 | 83 ± 5 | 84 ± 10 |

| MVC (U) | 68 ± 6 | 66 ± 5 | 95 ± 13 | 86 ± 10 |

| HVC (U) | 50 ± 8 | 45 ± 3 | 44 ± 6 | 40 ± 6 |

Units (U) for VC are (kHz·mmHg−1)103. Values are mean ± SEM. For abbreviations see Table 1 (Experiment 2).

Table 4.

Integrated (0–30 min) changes in cardiovascular variables following administration of retigabine (3 mg·kg−1)

| Pretreatment | Saline (n = 5) | Propranolol (n = 6) | CGP 20712A (n = 6) | ICI 118551 (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (AOC, beats) | +340 ± 219 | +0.2 ± 0.2* | +0.5 ± 0.3* | +57 ± 38 |

| HR (AUC, beats) | −409 ± 211 | −392 ± 56 | −461 ± 76 | −1055 ± 800 |

| MAP (mmHg min) | −205 ± 87 | −508 ± 39* | −391 ± 97 | −405 ± 179 |

| RVC (% min) | +220 ± 140 | +387 ± 98 | +266 ± 103 | +344 ± 166 |

| MVC (% min) | +77 ± 39 | +551 ± 117* | +288 ± 155 | +76 ± 25 |

| HVC (% min) | +726 ± 85 | +378 ± 72* | +877 ± 142 | +350 ± 146* |

Values are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 versus saline group (Kruskal–Wallis). For other abbreviations see Table 1 (Experiment 2).

AOC, area over the curve; AUC, area under the curve.

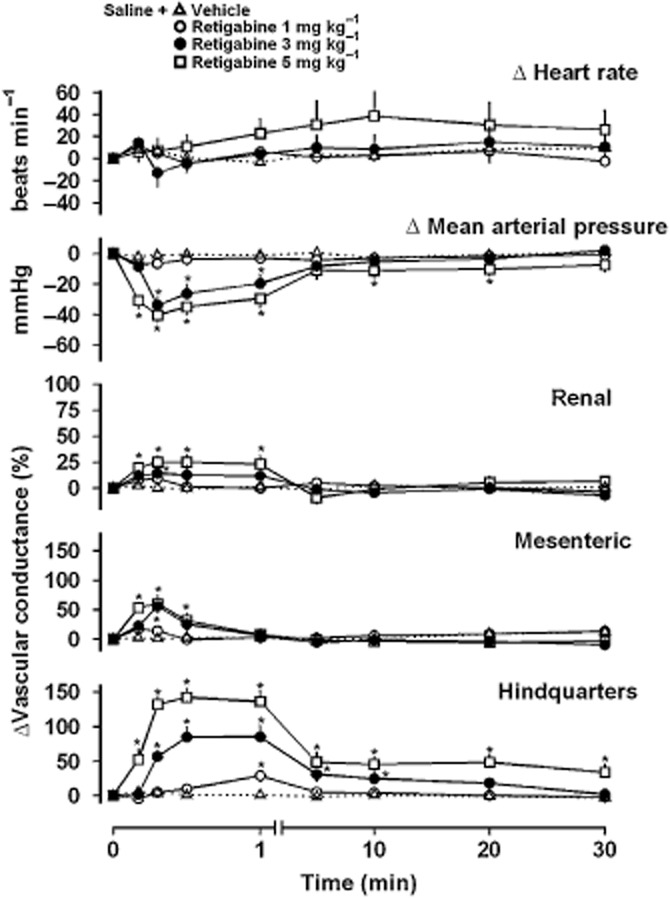

As above (see Experiment 1), in the presence of saline, retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) caused a variable heart rate response, and a reduction in BP accompanied by transient renal and mesenteric vasodilatations and a more prolonged hindquarters vasodilatation (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Haemodynamic effects of retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) in conscious rats treated with saline (n = 5, Figure 3A), propranolol (n = 6, Figure 3A), CGP 20712A (n = 6, Figure 3B) or ICI 118551 (n = 6, Figure 3B). Data points are mean and vertical bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05 versus baseline (Friedman's test). Between-group differences are given in the text (Experiment 2).

In the presence of propranolol, retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) caused hypotension and some vasodilatation in all three vascular beds (Figure 3A). Compared to responses seen in the saline-treated animals, the integrated (0–30 min) hypotensive and mesenteric vasodilator effects of retigabine were enhanced by propranolol, whereas the hindquarters vasodilatation was markedly reduced (Table 4). In propranolol-treated animals, there was a consistent bradycardic response to retigabine (Figure 3A, Table 4).

During infusion of the β1-adrenoceptor antagonist CGP 20712A, retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) caused similar BP and regional haemodynamic changes to those seen in the presence of saline (Figure 3B, Table 4), although under these conditions, as with propranolol, the heart rate response to retigabine was a consistent bradycardia (Figure 3B, Table 4).

In the presence of the β2-adrenoceptor antagonist ICI 118551, the heart rate, BP and renal and mesenteric vascular responses to retigabine (3 mg·kg−1) were not significantly different from those in the presence of saline, but the hindquarters vasodilatation was significantly attenuated [P < 0.05 integrated (0–30 min) responses vs. saline group; Figure 3B, Table 4].

Experiment 3: In vitro studies

The β1-adrenoceptor selective ligand CGP 20712A and the β2-selective ligand, ICI 118551, inhibited the specific binding of [3H]-CGP 12177 as expected. However, retigabine did not inhibit the specific binding of this ligand at either the β1- or β2-adrenoceptor at concentrations up to 1 mM (Figure 4A, Table 5).

Figure 4.

(A) Inhibition of [3H]-CGP12177 specific binding to β2–adrenoceptors expressed in CHO cells by retigabine, CGP 20712A and ICI 118551. Non-specific binding was determined by 10 μM propranolol and the concentration of [3H]-CGP 12177 in this experiment was 0.631 nM. This single experiment is representative of four separate experiments. (B) CRE-SPAP production in response to cimaterol in β1–adrenoceptors expressed in CHO cells in the absence and presence of retigabine. Bars represent basal CRE-SPAP production in response to 10 μM isoprenaline and in response to 1 μM, 10 μM or 100 μM retigabine alone. Data points are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. This single experiment is representative of four separate experiments. Data were provided by Dr Jillian Baker. Cell lines, methods and analysis as previously reported (Baker, 2005; Baker, 2010; Baker et al., 2011) (Experiment 3).

Table 5.

Log KD values obtained from [3H]-CGP 12177 whole-cell binding studies in CHO cells stably expressing either the human β1-adrenoceptor or the human β2-adrenoceptor

| ICI 118551 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGP 20712A | n | Log KD | n | Retigabine | n | |

| β1 | −8.98 ± 0.08 | 4 | −6.76 ± 0.03 | 4 | No binding | 4 |

| β2 | −5.88 ± 0.02 | 4 | −9.38 ± 0.04 | 4 | No binding | 4 |

Values are mean ± SEM for n separate experiments (Experiment 3).

CRE-SPAP production

Retigabine (1 μM, 10 μM and 100 μM) did not cause any rightward shift of the cimaterol concentration-response curve obtained at either subtype of β-adrenoceptor (expressed in CHO cells). Also, at concentrations up to 100 μM retigabine had no stimulating or inverse agonist effects on the responses to cimaterol (Figure 4B). Figure 4B shows a representative experiment in CHO cells expressing β1-receptors. Similar results were obtained in CHO cells expressing β2-receptors with retigabine concentrations up to 1 mM.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates, for the first time, the regional haemodynamic actions of retigabine in conscious rats. The main findings were that, under normotensive conditions, retigabine caused dose-dependent hypotension and hindquarters vasodilatation, together with transient renal and mesenteric vasodilatations. In rats made acutely hypertensive by an infusion of AII and AVP, the renal and mesenteric, but not the hindquarters vasodilator effects of higher doses of retigabine were enhanced. Furthermore, we obtained evidence indicating that β-adrenoceptors have a role in the hindquarters vasodilator effect of retigabine (β2) and in the heart rate response (β1). The data presented herein support the notion that Kv7 channels have a regulatory role in the maintenance of vascular tone, and suggest that retigabine, an activator of Kv7.2–7.5 channels, may have both direct and indirect effects in the vasculature.

Kv7 channels can be functionally expressed in renal and mesenteric arteries in vitro (Jepps et al., 2011; Chadha et al., 2012a), and evidence has been obtained suggesting that retigabine-induced vasorelaxation is mediated by an endothelium-independent mechanism (Joshi et al., 2006; Yeung et al., 2007). It is possible, therefore, that the renal and mesenteric vasodilatations are mediated via a direct action of retigabine on Kv7 channels in the vascular smooth muscle. However, the hindquarters responses are more complex and may involve the indirect activation of other intracellular pathways.

The current in vivo findings of the vasodilator effects of retigabine in normotensive, conscious rats are broadly consistent with the results from other studies on the role of Kv7 channels in the vasculature. Functional Kv7 channels have been identified in pulmonary arteries (Joshi et al., 2006), murine aorta, carotid, femoral and mesenteric arteries (Yeung et al., 2007), human visceral adipose and mesenteric arteries (Ng et al., 2011), and on baroreceptors (Wladyka et al., 2008) and sympathetic nerves (Brown and Adams, 1980). Activation of Kv7 channels in vitro, causes membrane hyperpolarization and smooth muscle relaxation, while inhibition of Kv7 channels leads to smooth muscle contraction (Yeung and Greenwood, 2005; Joshi et al., 2006; 2009; Yeung et al., 2007; Mackie et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2011). Moreover, in anaesthetized rats, it has been reported that activation of Kv7.2–7.5 channels with flupirtine, a structural analogue of retigabine, induces a reduction in mesenteric vascular resistance and BP (Mackie et al., 2008).

Recently, it was shown that Kv7 channel function and expression is disrupted in isolated vessels from two different rodent models of hypertension (Jepps et al., 2011). Accordingly, in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) and in AII-induced hypertensive mice, Kv7 channel activity was impaired, and the vasorelaxant effect of retigabine was diminished. The authors suggested that Kv7 channel-mediated responses were disrupted as a consequence of the development of hypertension, and this may contribute to the maintenance of an elevated BP (Jepps et al., 2011). Others have shown that the vasoactive peptide, AII, inhibits Kv7-mediated currents in sympathetic neurons and CHO cells (Zaika et al., 2006). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that Kv7-mediated currents are blocked by AVP through a PKC-dependent pathway (Brueggemann et al., 2007), in both mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells and in rat isolated mesenteric arteries (Mackie et al., 2008). These findings suggest that the vasoconstrictor action of AVP is mediated, at least in part, via inhibition of Kv7 channels. Both AII and AVP are thought to have important roles in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Hence, in the present study, we used AII-AVP to induce acute hypertension, and then measured the responses to retigabine under these conditions of increased vascular tone and BP. From the findings reported above, we predicted that the vasodilator effects of retigabine would be reduced under these hypertensive conditions, due to the disruptive effects of AII and AVP on Kv7 channel function. However, contrary to our predictions, the renal and mesenteric vasodilator effects of retigabine were actually enhanced during AII-AVP infusion, suggesting that the scope for Kv7 channel activation is increased under hypertensive conditions.

In previous in vivo experiments, it was found that AII causes vasoconstriction in the renal and mesenteric vascular beds, and AVP causes vasoconstriction in the mesenteric and, to a lesser extent, hindquarters vascular beds (Gardiner et al., 1988). Consistent with this, in the present study it was found that AII-AVP infusion caused a greater reduction in vascular conductance in the renal and mesenteric vascular beds compared with the hindquarters vasculature (Table 1). Therefore, it is possible that the enhanced vasodilator actions of retigabine during AII-AVP infusion were a reflection of the enhanced vascular tone, although it is notable that no enhancement in the vasodilator response to retigabine was observed in the hindquarters, given that AII-AVP also produced some degree of vasoconstriction in that vascular bed. While our results with AII-AVP do not provide any further mechanistic insight into the action of retigabine, they do show that under these acute hypertensive conditions, its vasodilator effect is not impaired.

It was clear from the initial studies that the time course, and possibly mechanism, of the vasodilator effect of retigabine in the hindquarters was quite different from that in the renal and mesenteric vascular beds. Since other experiments in this model have shown that prolonged hindquarters vasodilatation is mediated by β-adrenoceptors (Gardiner et al., 2010), we determined whether β-adrenoceptors are involved in the cardiovascular actions of retigabine by measuring the haemodynamic effects of retigabine during treatment with non-selective and selective β-adrenoceptor antagonists. In the presence of the β2-adrenoceptor antagonists (either propranolol or ICI 118551), the retigabine-induced increase in hindquarters vascular conductance was markedly attenuated, whereas in the presence of the selective β1-adrenoceptor antagonist (CGP 20712A) this effect of retigabine was unchanged. Interestingly, the β-adrenoceptor antagonists did not inhibit either the renal or mesenteric vascular effects of retigabine. It has been shown previously that the hindquarters vascular bed expresses a particularly high concentration of β2-adrenoceptors, and that β-adrenoceptor activation causes a marked hyperaemic hindquarters vasodilatation (Gardiner et al., 1991; 1992). Our results suggest that the observed retigabine-induced hindquarters vasodilatation is, at least in part, mediated by activation of β2-adrenoceptors. One explanation would be that retigabine acts as a β-adrenoceptor agonist. To address this possibility, we examined whether retigabine (i) elicits a response from functional β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, or (ii) binds to human β1- or β2-adrenoceptors, expressed in CHO cells. We have recently validated this in vitro binding assay as a predictor of ligand affinity and efficacy in vivo (Baker et al., 2011). However, our in vitro data clearly showed that retigabine has no β-adrenoceptor agonist (or, indeed, antagonist) properties. Another possibility is that retigabine indirectly causes β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatation via sympathetic activation. However, if this was due to a generalized sympathetic activation in the vasculature, then we would have seen a degree of vasoconstriction in the renal and mesenteric vascular beds due to the α-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of noradrenaline (Bennett et al., 2004), but this was not the case. Another hypothesis is that retigabine increases adrenomedullary adrenaline release, which then induces the hindquarters vasodilatation, although we know of no evidence to support this proposal.

The heart rate responses to retigabine deserve some comment. Under most conditions in the present experiments, the heart rate responses to retigabine were extremely variable, but in the presence of either propranolol or CGP 20712A, there was a clear-cut bradycardic effect of retigabine. These findings suggest that β-adrenoceptor-mediated tachycardia contributes to some extent to the heart rate response to retigabine in the intact animal, consistent with the suggestion of sympathoadrenal activation (see above). Recently, Kv7 channels were shown to be functional regulators of adrenergically controlled cardiomyocyte contraction rate (Zaika et al., 2011), further supporting the notion that Kv7 channels interact with the sympathetic nervous system to regulate heart rate. From the results of our experiments we cannot identify the mechanism for this bradycardic action of retigabine, but bradycardia in response to Kv7 channel activation has been reported in other animal models, including conscious, telemetred dogs (EMA, 2011) and anaesthetized rats (Mackie et al., 2008).

In conclusion, we have identified regional vascular effects of retigabine that change under hypertensive conditions and that are, in part, due to β-adrenoceptor activation. Although the exact mechanisms by which retigabine contributes to β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatations in the hindquarters vascular bed are not clear at this stage.

Most studies on Kv7 channels have focused on the neuronal effects of channel modulation, and it is only more recently that interest has developed in their involvement in cardiovascular effects. To date, Phase III clinical trials of retigabine (Brodie et al., 2010; French et al., 2011) have not reported any clinically relevant cardiovascular effects. However, it remains to be seen whether it has adverse effects during prolonged treatment or in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, such as hypertension. Altered Kv7 channel activity has been implicated in the pathogenesis of primary and secondary hypertension in animal models, where a strong role for these channels in the development of hypertension is emerging (Jepps et al., 2011; Chadha et al., 2012a). In a very recent study, it was shown that the impaired anticontractile effects of periadventitial adipose tissue in skeletal muscle vessels from SHRs can be restored by administration of Kv7 channel openers such as retigabine (Zavaritskaya et al., 2013). These findings further support the proposal that Kv7 channels are a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of vascular diseases associated with inappropriate vasoconstriction. Zavaritskaya et al. (2013) also showed that retigabine induced similar ex vivo vasorelaxant effects in the gracilis artery, and in vivo hypotensive responses in SHRs compared to normotensive control rats, which is perhaps surprising given the results of background studies by Jepps et al. (2011), where the vasorelaxant effects of various Kv7 channel openers were found to be reduced in isolated vessels from SHRs. However, in the latter study (Jepps et al., 2011), it was notable that retigabine-induced vasorelaxations were less affected than those to two other structurally different Kv7 channel openers, which had differing subunit specificities.

To the best of our knowledge, the data from the present study are the first to show the regional haemodynamic effects of Kv7 channel activation during acute hypertension in vivo. We believe that this body of work provides an important insight into the complex functions of Kv7 channel activation in the cardiovascular system, highlighting direct and indirect vascular control mechanisms and a significant interaction with the sympathoadrenal system. Future work is required to assess the impact of such mechanisms in pathophysiological conditions, and following prolonged treatment with retigabine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Sheila Gardiner for her support and guidance throughout this project, Julie March and Philip Kemp for their assistance with the in vivo work, and Richard Proudman and Dr Jillian Baker for kindly providing the in vitro data and analysis. This work was supported by a University of Nottingham funded Career Development Fellowship (LVF).

Glossary

- AII

angiotensin II

- AVP

arginine vasopressin

- CGP 20712A

1-[2-((3-carbamoyl-4-hydroxy)phenoxy)ethylamino]-3-[4-(1-methyl-4-trifluoromethyl-2-imidazolyl)phenoxy]-2-propanol dihydrochloride

- ICI 118551

(±)-erythro-(S*,S*)-1-[2,3-(dihydro-7-methyl-1H-inden-4-yl)oxy]-3-[(1-methylethyl)amino]-2-butanol hydrochloride

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG. The selectivity of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists at the human beta1, beta2 and beta3 adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:317–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG. A full pharmacological analysis of the three turkey β-adrenoceptors and comparison with the human β-adrenoceptors. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Kemp P, March J, Fretwell L, Hill SJ, Gardiner SM. Predicting in vivo cardiovascular properties of β-blockers from cellular assays: a quantitative comparison of cellular and cardiovascular pharmacological responses. FASEB J. 2011;25:4486–4497. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-192435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett T, Mahajan RP, March JE, Kemp PA, Gardiner SM. Regional and temporal changes in cardiovascular responses to norepinephrine and vasopressin during continuous infusion of lipopolysaccharide in conscious rats. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:400–407. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickel N, Gandhi P, VanLandingham K, Hammond J, DeRossett S. The urinary safety profile and secondary renal effects of retigabine (ezogabine): a first-in-class antiepileptic drug that targets KCNQ (K(v)7) potassium channels. Epilepsia. 2012;53:606–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MJ, Lerche H, Gil-Nagel A, Elger C, Hall S, Shin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2010;75:1817–1824. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd6170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature. 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Passmore GM. Neural KCNQ (Kv7) channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1185–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemann LI, Moran CJ, Barakat JA, Yeh JZ, Cribbs LL, Byron KL. Vasopressin stimulates action potential firing by protein kinase C-dependent inhibition of KCNQ5 in A7r5 rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1352–H1363. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00065.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha PS, Zunke F, Zhu HL, Davis AJ, Jepps TA, Olesen SP, et al. Reduced KCNQ4-encoded voltage-dependent potassium channel activity underlies impaired β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of renal arteries in hypertension. Hypertension. 2012a;59:877–884. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha PS, Zunke F, Davis AJ, Jepps TA, Linders JT, Schwake M, et al. Pharmacological dissection of K(v)7.1 channels in systemic and pulmonary arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2012b;166:1377–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto MA, Weisenberg JL, Wong M. Clinical utility, safety, and tolerability of ezogabine (retigabine) in the treatment of epilepsy. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2012;4:81–86. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S28814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMA (European Medicines Agency) 2011. CHMP assessment report: retigabine. Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/001245.

- Ferron GM, Paul J, Fruncillo R, Richards L, Knebel N, Getsy J, et al. Multiple-dose, linear, dose-proportional pharmacokinetics of retigabine in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:175–182. doi: 10.1177/00912700222011210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JA, Abou-Khalil BW, Leroy RF, Yacubian EM, Shin P, Hall S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ezogabine (retigabine) in partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2011;76:1555–1563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182194bd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, Bennett T, Compton AM. Regional haemodynamic effects of neuropeptide Y, vasopressin and angiotensin II in conscious, unrestrained, Long Evans and Brattleboro rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1988;24:15–27. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, Kemp PA, Bennett T. Effects of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester on vasodilator responses to acetylcholine, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine or salbutamol in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1725–1732. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, Kemp PA, Bennett T, Bose C, Foulkes R, Hughes B. Involvement of beta 2-adrenoceptors in the regional haemodynamic responses to bradykinin in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:839–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, March JE, Kemp PA, Bennett T, Baker DJ. Possible involvement of GLP-1(9-36) in the regional haemodynamic effects of GLP-1(7-36) in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161:92–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Fujii K, Abe I. Impaired beta-adrenergic hyperpolarization in arteries from prehypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;37:609–613. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe MJ, Large CH, Sankar R. The mechanism of action of retigabine (ezogabine), a first-in-class K+ channel opener for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:412–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WS, Gardiner SM. Acute hypertension reveals depressor and vasodilator effects of cannabinoids in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti FA, Panza E, Barrese V, Viggiano D, Soldovieri MV, Taglialatela M. Expression, localization, and pharmacological role of Kv7 potassium channels in skeletal muscle proliferation, differentiation, and survival after myotoxic insults. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:811–820. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepps TA, Chadha PS, Davis AJ, Harhun MI, Cockerill GW, Olesen SP, et al. Downregulation of Kv7.4 channel activity in primary and secondary hypertension. Circulation. 2011;124:602–611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepps TA, Olesen SP, Greenwood IA. One man's side effect is another man's therapeutic opportunity: targeting Kv7 channels in smooth muscle disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Balan P, Gurney AM. Pulmonary vasoconstrictor action of KCNQ potassium channel blockers. Respir Res. 2006;7:31–41. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Sedivy V, Hodyc D, Herget J, Gurney AM. KCNQ modulators reveal a key role for KCNQ potassium channels in regulating the tone of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:368–376. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie AR, Brueggemann LI, Henderson KK, Shiels AJ, Cribbs LL, Scrogin KE, et al. Vascular KCNQ potassium channels as novel targets for the control of mesenteric artery constriction by vasopressin, based on studies in single cells, pressurized arteries, and in vivo measurements of mesenteric vascular resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:475–483. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main MJ, Cryan JE, Dupere JR, Cox B, Clare JJ, Burbidge SA. Modulation of KCNQ2/3 potassium channels by the novel anticonvulsant retigabine. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:253–262. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn-St James M, Glanville J, McCool R, Duffy S, Cooper J, Hugel P, et al. The efficacy and safety of retigabine and other adjunctive treatments for refractory partial epilepsy: a systematic review and indirect comparison. Seizure. 2008;21:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F, Soldovieri MV, Martire M, Taglialatela M. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic potential of neuronal Kv7-modulating drugs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;8:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft I, Murray A, Nilsen M, Gurney AM, MacLean MR. Treatment with the Kv7 potassium channel activator flupirtine is beneficial in two independent mouse models of pulmonary hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1241–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng FL, Davis AJ, Jepps TA, Harhun MI, Yeung SY, Wan A, et al. Expression and function of the K+ channel KCNQ genes in human arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto JF, Kimball MM, Wilcox KS. Effects of the anticonvulsant retigabine on cultured cortical neurons: changes in electroresponsive properties and synaptic transmission. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:921–927. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundfeldt C, Netzer R. The novel anticonvulsant retigabine activates M-currents in Chinese hamster ovary-cells tranfected with human KCNQ2/3 subunits. Neurosci Lett. 2000;282:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, Grippon S, Kirkpatrick P. Ezogabine (retigabine) Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:729–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streng T, Christoph T, Andersson KE. Urodynamic effects of the K+ channel (KCNQ) opener retigabine in freely moving, conscious rats. J Urol. 2004;172:2054–2058. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138155.33749.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Cao X, Wang K. A novel degradation signal derived from distal C-terminal frameshift mutations of KCNQ2 protein which cause neonatal epilepsy. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42949–42958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodorsson-Norheim E. Friedman and Quade tests: BASIC computer program to perform nonparametric two-way analysis of variance and multiple comparisons on ranks of several related samples. Comput Biol Med. 1987;17:85–99. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(87)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden AD, Yu W, Zou A, Jegla T, Wagoner PK. Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:591–600. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wladyka CL, Feng B, Glazebrook PA, Schild JH, Kunze DL. The KCNQ/M-current modulates arterial baroreceptor function at the sensory terminal in rats. J Physiol. 2008;586:795–802. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SY, Greenwood IA. Electrophysiological and functional effects of the KCNQ channel blocker XE991 on murine portal vein smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:585–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SY, Pucovský V, Moffatt JD, Saldanha L, Schwake M, Ohya S, et al. Molecular expression and pharmacological identification of a role for K(v)7 channels in murine vascular reactivity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:758–770. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O, Lara LS, Gamper N, Hilgemann DW, Jaffe DB, Shapiro MS. Angiotensin II regulates neuronal excitability via phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent modulation of Kv7 (M-type) K+ channels. J Physiol. 2006;575:49–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O, Zhang J, Shapiro MS. Functional role of M-type (KCNQ) K+ channels in adrenergic control of cardiomyocyte contraction rate by sympathetic neurons. J Physiol. 2011;589:2559–2568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.204768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaritskaya O, Zhuravleva N, Schleifenbaum J, Gloe T, Devermann L, Kluge R, et al. Role of KCNQ channels in skeletal muscle arteries and periadventitial vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2013;61:151–159. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]