Abstract

Background and Purpose

We previously reported that adenosine, acting at adenosine A2A receptors (A2AR), inhibits osteoclast (OC) differentiation in vitro (A2AR activation OC formation reduces by half) and in vivo. For a better understanding how adenosine A2AR stimulation regulates OC differentiation, we dissected the signalling pathways involved in A2AR signalling.

Experimental Approach

OC differentiation was studied as TRAP+ multinucleated cells following M-CSF/RANKL stimulation of either primary murine bone marrow cells or the murine macrophage line, RAW264.7, in presence/absence of the A2AR agonist CGS21680, the A2AR antagonist ZM241385, PKA activators (8-Cl-cAMP 100 nM, 6-Bnz-cAMP) and the PKA inhibitor (PKI). cAMP was quantitated by EIA and PKA activity assays were carried out. Signalling events were studied in PKA knockdown (lentiviral shRNA for PKA) RAW264.7 cells (scrambled shRNA as control). OC marker expression was studied by RT-PCR.

Key Results

A2AR stimulation increased cAMP and PKA activity which and were reversed by addition of ZM241385. The direct PKA stimuli 8-Cl-cAMP and 6-Bnz-cAMP inhibited OC maturation whereas PKI increased OC differentiation. A2AR stimulation inhibited p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in control but not in PKA KO cells. A2AR stimulation activated ERK1/2 by a PKA-dependent mechanism, an effect reversed by ZM241385, but not p38 and JNK activation. A2AR stimulation inhibited OC expression of differentiation markers by a PKA-mechanism.

Conclusions and Implications

A2AR activation inhibits OC differentiation and regulates bone turnover via PKA-dependent inhibition of NFκB nuclear translocation, suggesting a mechanism by which adenosine could target bone destruction in inflammatory diseases like Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Keywords: adenosine A2A receptor, osteoclast inhibition, ERK1/2, PKA, p50/p105 NFκB

Introduction

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells (MNCs) derived from myeloid precursors that, under normal homeostatic conditions, degrade bone to initiate normal bone remodelling and mediate bone loss in pathologic conditions by increasing their resorptive activity. Osteoclasts secrete hydrochloric acid and proteases [cathepsin K and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) among others] into discrete loci on the surface of the bone (Vaananen et al., 2000). Osteoclast differentiation in vitro depends on the combination of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor for activation of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL/TRANCE). RANKL binds to its receptor RANK (Receptor activator of NFκB) and M-CSF binds to its receptor, c-fms, resulting in the recruitment of TNF receptor associated factors (TRAF), followed by activation signalling through MAPK, NFκB, c-Fos, phospholipase Cγ and nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1) (Wei et al., 2002; Boyce et al., 2009; Hirata et al., 2010).

Adenosine, the metabolic product of adenine nucleotide dephosphorylation, is generated during oxidative stress, ischaemia and hypoxia. It is generated both intracellularly and extracellularly and exerts its physiologic and pharmacologic effects extracellularly via activation of specific cell surface G protein coupled receptors (A1, A2A, A2B and A3), each of which has a unique pharmacological profile (Fredholm et al., 2011). Classically, adenosine receptors were subdivided on the basis of their effects on adenylyl cyclase activity, inhibition (A1 and A3 receptor) and stimulation (A2A and A2B receptors) (van Calker et al., 1979; Londos et al., 1980; Verzijl and Ijzerman, 2011). Both A2A and A2B receptors stimulate the formation of cAMP and, depending on the cell type, increase intracellular calcium levels and phospholipase C mobilization (Fredholm et al., 2001; Jacobson and Gao, 2006). Adenosine receptors have been reported to activate MAPKs in a variety of cells, which further mediate downstream signalling events (Verzijl and Ijzerman, 2011). Thus, for example, we have previously reported that the adenosine A2A receptor stimulates hepatic stellate cells to produce collagen 1 via a signalling pathway that includes ERK1/2 but promotes collagen 3 expression via a p38MAPK-dependent pathway (Hirano et al., 1996; Sexl et al., 1997). Interestingly, adenosine A1 and A2 receptors (A1R and A2R) have opposing functional effects (Schulte and Fredholm, 2003). For example, during inflammation, adenosine A1R promotes multinucleated giant cell formation from human peripheral blood monocytes whereas the A2AR inhibits multinucleated giant cell formation (Merrill et al., 1997). Similarly, A1 receptor blockade or deletion leads to diminish in vitro osteoclast formation and A2A stimulation diminishes osteoclast formation.

Previously, we have reported that A2A receptors inhibit M-CSF/RANKL-stimulated osteoclast differentiation and function (Mediero et al., 2012b) and the selective A2AR agonist CGS21680 reduced in vivo wear particle-induced bone pitting and porosity, increasing cortical bone and bone volume compared to control mice (Mediero et al., 2012a). Similarly, methotrexate, the gold standard drug in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, mediates many of its anti-inflammatory effects by increasing release of adenosine which stimulates A2A and A3 receptors to diminish inflammation and bony erosions (Chan and Cronstein, 2010). To better understand the role of adenosine and its receptors in the suppression of inflammatory bone resorption, we determined which intracellular pathways are involved in A2AR-mediated regulation of osteoclast differentiation.

Methods

Reagents

RAW264.7 cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Recombinant mouse M-CSF and recombinant mouse RANKL were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). A2AR specific agonist CGS21680 and A2AR specific antagonist ZM241385 were from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA). α-MEM, FBS and penicillin/streptomycin were from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Sodium acetate, glacial acetic acid, Naphtol AS MX phosphate disodium salt, fast red violet LB, RIPA buffer, protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, hexadimethrine bromide, lentivirus packing particles [scrambled and protein kinase A (PKA) catalytic alpha subunit] and puromycin selection marker were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sodium Tartrate was from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). 8-Bromoadenosine-3’,5'-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP) and N6-Benzoyladenosine-3’,5'-cyclic monophosphate (6-Bnz-cAMP) were from BIOLOG Life Science Institute (San Diego, CA, USA). The PKA inhibitor (TTYADFIASGRTGRRNAIHD) (PKI) was from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-PKA catalytic, mouse monoclonal anti-Phospho-ERK1/2, mouse monoclonal anti-ERK2, mouse monoclonal anti-Phospho-JNK, mouse monoclonal anti-JNK, rabbit polyclonal anti-actin, goat anti-rabbit-AP and goat anti-mouse-AP were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-p-p38 was from Promega. Mouse monoclonal anti-p38 was from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-NFκB p50/p105, rabbit polyclonal anti-IκB alpha, rabbit polyclonal anti-p-IκB alpha and mouse monoclonal anti-nuclear matrix protein p84 were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). cAMP Biotrak Enzymeimmunoassay system was from Amersham (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Pep-Tag® assay for non-radioactive detection of cAMP-dependent protein kinase was purchase from Promega. The MEK inhibitor (U0126), p38 inhibitor (SB203580) and JNK inhibitor II (SP600125) were from Calbiochem (EMD Millipore Chemicals, Philadelphia, PA, USA). NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents kit and BCA Protein Assay Reagent were from Thermo Scientific (Pierce Protein Research Products, IL, Rockford, USA). NFκB (p65) transcription factor assay kit was purchase from Cayman Chemical Company (Miami, FL, USA).

Osteoclast differentiation

The New York University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols related to animals. Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were isolated from 6–8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice as previously described (Mediero et al., 2012b). Briefly, marrow cavity was flushed out with α-MEM from femora and tibiae aseptically removed, and bone marrow was incubated overnight in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (αMEM) to obtain a single-cell suspension. About 200 000 non-adherent cells were collected and seeded in α-MEM with 30 ng·mL−1 M-CSF for 2 days. At day 3 (day 0 of differentiation), 30 ng·mL−1 RANKL was added to the culture together with CGS21680 1 μM alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM and in the presence PKA activators 8-Cl-cAMP and 6-Bnz-cAMP 100 nM each and the PKA inhibitor PKI 10 μg·mL−1 (n = 6 each assay). Cultures were fed every third day by replacing the culture medium with fresh medium and reagents. Five thousand RAW264.7 cells were differentiated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM, 8-Cl-cAMP, 6-Bnz-cAMP 100 nM each and PKI 10 μg·mL−1 (n = 5 each assay). After incubation for 7 (BMCs) or 3 days (RAW264.7 cells), cells were prepared for TRAP staining for osteoclast quantification (Mediero et al., 2012a,b). The number of TRAP-positive MNCs containing ≥3 nuclei/cell were scored (Yasuda et al., 1999). In all experiments, DMSO is added to control in the same concentration, as it is present in conditions containing various agonists and antagonists.

Transfection protocol

RAW264.7 cells (15 000 cells·mL−1) were plated and 24 h later, cells were incubated in the presence of Hexadimethrine Bromide (4 μg·mL−1) and 108 lentiviral transduction particles corresponding to mouse PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA (SHCLNV-NM_008854), with puromycin selection marker, for another 24 h to allow transfection. Media was then replaced with αMEM containing puromycin (1 ug·mL−1), changing the media every 3 days until selected clones formed. These clones were isolated and expanded until confluence. Scrambled shRNA (SHC002V) is used as control. Permanently silenced clones are kept in culture under puromycin selection.

cAMP measurements

Intracellular cAMP was measured with the Amersham cAMP Biotrak Enzymeimmunoassay system using the non-acetylation EIA procedure following protocol. Briefly, 105 RAW264.7 cells were plated and incubated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (30 min pre-incubation) for different time points (n = 6 each) and the recommended protocol was followed. Optical density was read at 450 nm and results were calculated as described by the manufacturer.

PKA activation during osteoclast differentiation

Pep-Tag® assay for non-radioactive detection of cAMP-dependent protein kinase was used following recommendations. The PepTag Assay uses a brightly, coloured, fluorescent peptide substrate that is highly specific for PKA. Phosphorylation by PKA of its specific substrate alters the peptide's net charge from +1 to −1. This change in the net charge of the substrate allows the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated versions of the substrate to be rapidly separated on an agarose gel. The phosphorylated species migrates towards the positive electrode, while the non-phosphorylated substrate migrates towards the negative electrode. The amino acid sequence of the PKA-specific peptide substrate, PepTagR A1 Peptide, is L-R-R-A-S-L-G (Kemptide). Briefly, 2.5 × 106 RAW264.7 cells or BMCs derived osteoclasts from A2A receptor knockout (A2AKO) mice (a gift of Dr. Jiang Fan Chen, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA) (Chen et al., 1999) were incubated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL (and 50 ng·mL−1 MCS-F in the case of primary BMCs derived osteoclasts) together with CGS21680 1 μM alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (30 min pre-incubation) for 15 min (n = 4) were homogenized in cold PKA extraction buffer and 10 μL of the resultant samples were analysed following the protocol. A spectrophotometric method was used to quantitate kinase activity. Optical density was read at 570 nm, and activity was calculated following protocol recommendations.

Western blot

For Western blot analysis of PKA, pERK1/2, p-p38, pJNK expression and NFκB nuclear translocation, PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA transfected RAW264.7 cells (shRNA PKA) (or scrambled shRNA as control) and primary bone marrow-derived cells (from wild type and A2AKO mice) were activated with 50 ng·mL−1 of RANKL (and 50 ng·mL−1 MCS-F in the case of primary BMCs) and challenged with CGS21680 1 μM (alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM) and U0126, SB253085 or SP600125 10 μM each (30 min pretreatment) (n = 4 each) were collected at different time points and lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease/phosphatase inhibitors to extract total cell protein content. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction protein extraction was performed using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents kit. Protein concentration was determined by BCA. Four or 10 μg of protein was subjected to 7.5 or 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. To block non-specific binding, membranes were treated in TBS/Tween-20 0.05% with 5% skimmed milk 1 h at room temperature, and membranes where incubated overnight 4°C with primary antibodies against PKA catalytic 1:1000, pERK1/2 1:1000, p-p38 1:1000, pJNK 1:500, p50/p105 NFκB 1:5000, IκB alpha 1:500 and p-IκB alpha 1:500. After washing with TBS/Tween-20 0.05%, membranes were incubated with goat–anti-rabbit-AP 1:2000 or goat-anti-mouse-AP 1:3000. Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (GE Healthcare) in Typhoon Trio equipment. Blots were reprobed with ERK2, p38, JNK or actin diluted 1:1000, to check that all lanes were loaded with the same amount of protein. Specific nuclear signal was detected using mouse monoclonal anti-nuclear matrix protein p84 diluted 1:1000. Intensities of the respective band are examined by densitometric analysis using the KODAK Gel Logic 2000 and KODAK Molecular Imaging Software.

To quantify Western blot analysis digital densitometric band analysis was performed and band intensities were expressed relative to ERK2, p38, JNK, actin or p84, as appropriate. Variations in intensity were expressed as % of control and expressed as mean ± SEM. All results were calculated as a percentage of non-stimulated controls to minimize the intrinsic variation among different experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way anova and Bonferroni post-test and the levels of significance were indicated in the figure legends.

NFκB (p65) transcription factor assay

NFκκB (p65) transcription factor assay was carried out following the manufacturers’ instructions. Cayman's NFκB (p65) transcription factor assay is a non-radioactive, sensitive method (ELISA method) for detecting specific transcription factor DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts and whole cell lysates. A specific double stranded DNA (dsDNA) sequence containing the NFκB response element is immobilized to the wells. NFκB contained in a nuclear extract, binds specifically to the NFκB response element, and NFκB (p65) is detected by addition of specific antibodies. Briefly, 107 RAW264.7 cells were plated and incubated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (30 min pre-incubation) for different time points (n = 5 each). Nuclear extracts were purified following the protocol and the specific transcription factor DNA binding activity was measured following the protocol. Optical density was read at 450 nm and results were calculated as described by the manufacturer.

Quantitative real-time RT–PCR

To confirm the activation of PKA in A2AR osteoclast differentiation modulation, we measured the activation of the two osteoclast differentiation markers, cathepsin K and NFATc1, and osteopontin, an extracellular structural protein that initiates the development of osteoclast ruffled borders, in PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA transfected RAW264.7 cells (and scrambled shRNA for control) activated with 50 ng·mL−1 of RANKL and challenge with CGS21680 1 μM (alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM) (n = 4 each assay) by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT–PCR). Cells were collected during the 3 days of differentiation and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Invitrogen) including sample homogenization with QIAshredder columns. Oncolumn DNA digestion was performed to avoid genomic DNA contamination. 0.5 μg of total RNA was retrotranscribed using MuLV Reverse transcriptase PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at 2.5U/μL, including in the same reaction RNase inhibitor 1 U/μL, random hexamers 2.5U/μLm MgCl2 5 mM, PCR buffer II 1X and dNTPs 1 mM. RT–PCR was used to relative quantification of gene expression using a Stratagene Mx3005P (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA, USA) with Brilliant Fast SYBR Green Kit QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene). The following primers were used: Cathepsin K Forward: 5'- GCTGAACTCAGGACCTCTGG-3’ and Reverse: 5'- GAAAAGGGAGGCATGAATGA-3’; NFATc1 Forward: 5'- TCATCCTGTCCAACACCAAA-3’ and Reverse: 5'- TCACCCTGGTGTTCTTCCTC -3’; Osteopontin Forward: 5'-TCTGATGAGACCGTCACTGC-3’ and Reverse: 5'- TCTCCTGGCTCTCTTTGGAA-3’ and GAPDH Forward: 5'-CTACACTGAGGACCAGGTTGTCT-3’ and Reverse: 5'- GGTCTGGGATGGAAATTGTG-3’ (Mediero et al., 2012a). The Pfaffl method (Pfaffl, 2001) was used for relative quantification of Cathepsin K, NFATc1 and Osteopontin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance for differences between groups was determined by use of one-way anova and Bonferroni post-test. All statistics were calculated using GraphPad® software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

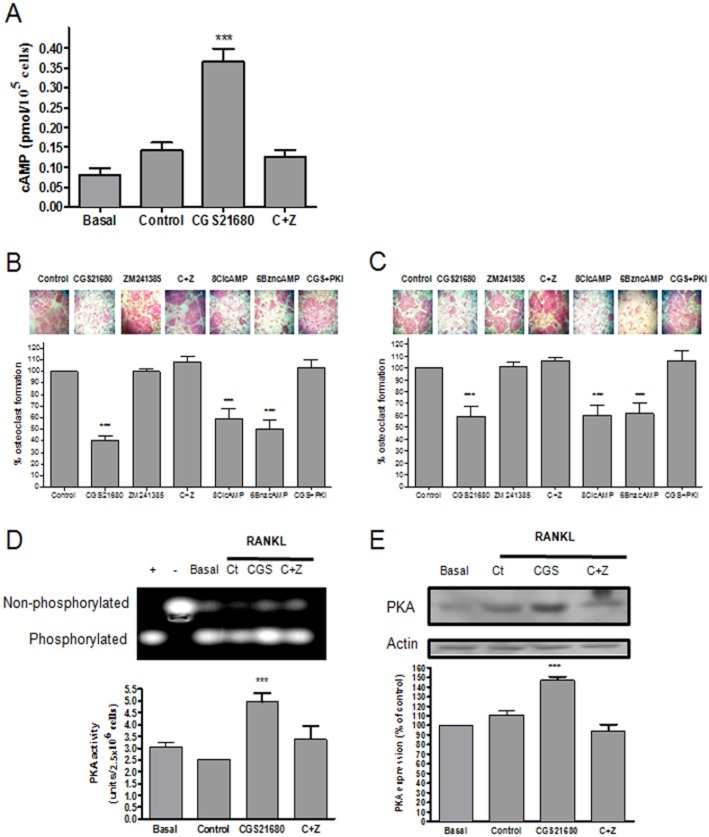

Adenosine A2AR activation stimulates an increase in cellular cAMP levels as well as PKA activation

When RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL, intracellular cAMP levels were not significantly increased (0.14 ± 0.02 pmol/105 cells after 10 min stimulation vs. 0.08 ± 0.02 pmol/105 cells basal levels, P = NS, n = 6) (Figure 1A), but stimulation of these cells with the A2A agonist CGS21680 1 μM, increased cAMP values nearly threefold (0.35 ± 0.03 pmol/105 cells for CGS21680, P < 0.001 vs. control, n = 6) (Figure 1A). Pretreatment of RAW264.7 cells with the selective A2AR antagonist ZM241385 (1 μM) completely blocked the effect of the A2A agonist (0.13 ± 0.01 pmol/105 cells, P = NS vs. control, n = 6) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Adenosine A2AR activation increased cAMP production and increased PKA activation. BMCs and RAW264.7 cells were treated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z), 8-Cl-cAMP and 6-Bnz-cAMP 100 nM each and PKI 10 μg·mL−1. (A) Intracellular cAMP levels were measured after 10 min stimulation. cAMP values are expressed as the mean ± SEM pmol/105 cells (n = 6). (B) Primary bone marrow cell-derived osteoclasts were fixed and stained for TRAP. TRAP+ cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6) (C) RAW264.7 derived osteoclast were fixed and stained for TRAP following the same conditions as primary cells. TRAP+ cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). PKI + CGS216580 TRAP+ cells are expressed as % of PKI-treated cells alone. (D) PKA activity was calculated 15 min after RAW264.7 cells stimulation. Gel image reflect separation of phosphorylated/non-phosphorylated peptide migration. Data were express as the mean ± SEM in units/2.5 × 106 cells considering the relation of phosphorylated Peptide A1 and PKA activity according to manufacturer's indication (n = 4). + indicate positive control and – indicate negative control. (E) PKA expression was analysed 8 h after RAW264.7 cell stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with actin and results were normalized to the density of the actin bands. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 versus non-stimulated control.

Adenosine A2AR activation inhibits osteoclast formation via activation of protein kinase A (PKA)

Because cAMP signals within the cell proceed via activation of two different pathways following intracellular activation of two main sensor proteins PKA and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) we sought to determine which pathway was responsible for the effects of A2A receptor stimulation on osteoclast differentiation. To answer this question, we tested the effect of direct activation of PKA with the cAMP analogues 8-Cl-cAMP and 6-Bzn-cAMP or inhibition of its activity with the inhibitor (PKI) on M-CSF/RANKL-stimulated osteoclast formation by RAW264.7 cells. As previously described for primary murine BMCs (Mediero et al., 2012b), CGS21680 1 μM inhibited osteoclast differentiation (41 ± 9% maximal inhibition, P < 0.001, n = 6), an effect completely blocked by ZM241385 1 μM pretreatment (106 ± 3% of control, P < 0.001, n = 6) (Figure 1B). Both PKA-selective cAMP analogues 8-Cl-cAMP and 6-Bnz-cAMP (100 nM) inhibited osteoclast differentiation to the same extent as the A2AR agonist (40 ± 9% and 39 ± 9% inhibition, respectively, P < 0.001, n = 6) whereas the selective PKA inhibitor (PKI) increased osteoclast differentiation in the presence of CGS21680 (106 ± 7% of control, P < 0.001, n = 6) (Figure 1B). We studied the effects of the same agents on primary murine BMCs and found substantially identical results (Figure 1C). Because the effects of these signalling pathway agents were identical in the cell line and primary cells we carried out the remainder of these studies with the RAW264.7 cell line.

To confirm that the effects of the PKA activators and inhibitor on osteoclast differentiation were directly related to the effects of these agents on PKA we determined PKA activity in cell lysates directly using a specific fluorescent peptide substrate for PKA. Treatment with RANKL alone (Control) does not affect PKA activity (2.7 ± 0.2 unit/2.5 × 106 cells vs. 3.1 ± 0.2 unit/2.5 × 106 cells basal, P = NS, n = 4) but A2AR stimulation nearly doubles the cellular activity (from 3.1 ± 0.2 units/2.5 × 106 cells to 4.96 ± 0.2 units/2.5 × 106 cells, P < 0.001, n = 4) (Figure 1D), an effect completely blocked by treatment of the cells with the A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 (3.4 ± 0.3 units/2.5 × 106 cells, P = NS vs. control, n = 4) (Figure 1D). Interestingly, stimulation of the A2AR by CGS21680 1 μM increased PKA expression after 8 h stimulation (147 ± 4% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4) (Figure 1E), an effect completely blocked by the pharmacologic antagonist ZM241385.

We also studied PKA activity in cell lysates from osteoclasts differentiated from primary marrow cells from A2AKO mice (Supporting Information Figure S2A). As observed in the RAW cells, RANKL alone (Control) did not affect PKA activity (3.3 ± 0.1unit/2.5 × 106 cells vs. 2.5 ± 0.2 unit/2.5 × 106 cells basal, P = NS, n = 3), and neither pretreatment with CGS21680 nor ZM241385 affected PKA activity (3.4 ± 0.2 unit/2.5 × 106 cells and 2.9 ± 0.1 unit/2.5 × 106 cells respectively, P = NS, n = 3).

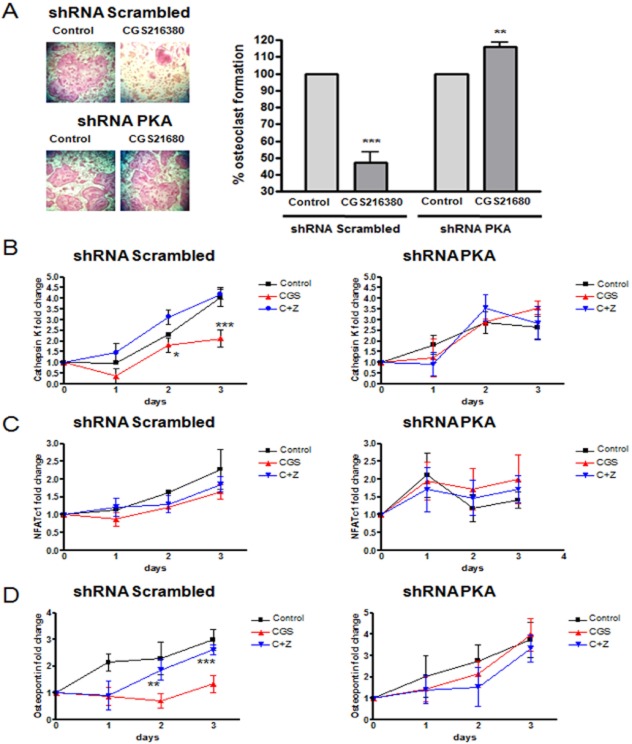

Silencing of PKA blocks the effect of A2AR activation on osteoclast differentiation

In order to determine the involvement of PKA in the A2AR-mediated inhibition of osteoclast maturation, we knocked down the PKA catalytic alpha subunit by infecting RAW264.7 cells with lentiviral particles containing shRNA for PKA catalytic alpha subunit and selected the relevant infected cells with puromycin. As control, we infected cells with vector containing scrambled shRNA. As noted in Figure 2A, silencing of the PKA catalytic alpha subunit abrogated the inhibition of osteoclast differentiation due to A2AR activation (116.2 ± 2.5% of control, P < 0.01, n = 4). To confirm that the PKA knockdown blocked A2AR-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation, we determined the effect of the A2A agonist on expression of mRNA for markers of osteoclast differentiation. As we have previously observed in primary cells (Mediero et al., 2012b), we noted that both RANKL alone (Control) or ZM241385 1 μM pretreatment in RAW264.7 scrambled cells increased the expression of mRNA for Cathepsin K (by up to 4 ± 0.7 fold change on day 3, P < 0.001, n = 4) and treatment with CGS21680 (1 μM) reduced this increase by half (2 ± 0.05-fold decrease, P < 0.001, n = 4), an effect that was completely lost in shRNA PKA cells (Figure 2B). Interestingly, NFATc1 mRNA expression was up-regulated during osteoclast differentiation under all conditions studied both in the scrambled shRNA infected cells and in the shRNA PKA cells (up to 2 ± 0.6-fold on day 3 of differentiation, P < 0.001, n = 4, Figure 2C). Finally, mRNA expression for osteopontin was also increased in the RANKL-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (scrambled cells) alone (Control) or after pretreatment with ZM241385 (1 μM, by up to 3 ± 0.1-fold change on day 3, P < 0.001, n = 4). In contrast, treatment with CGS21680 prevented the RANKL-mediated increase in mRNA levels and this effect was lost in the shRNA PKA cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Expression of osteoclast differentiation markers mRNA in PKA catalytic alpha subunit knockdown cells. (A) RAW264.7 cells were permanently transfected with scrambled or PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA, and treated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 (1 μM). TRAP-positive cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. The results were expressed as the means of four different assays in duplicate. The y axis have been expanded to show the difference more clearly. (B) Changes in Cathepsin K mRNA in osteoclasts during the osteoclast differentiation process in the presence of CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or with ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z) in PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA RAW264.7 cells compared to scrambled shRNA. (C) NFATc1 mRNA fold change in RANKL derived osteoclast during the three days osteoclast differentiation process in the presence of 1 μM (CGS) alone or with ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z) in PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA RAW264.7 cells compared to scrambled shRNA infected cells. (D) Changes in Osteopontin mRNA in RANKL derived osteoclast during the three days osteoclast differentiation process in the presence of CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or with ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z) in PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA RAW264.7 cells compared to scrambled shRNA infected cells. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.5 versus non-stimulated control.

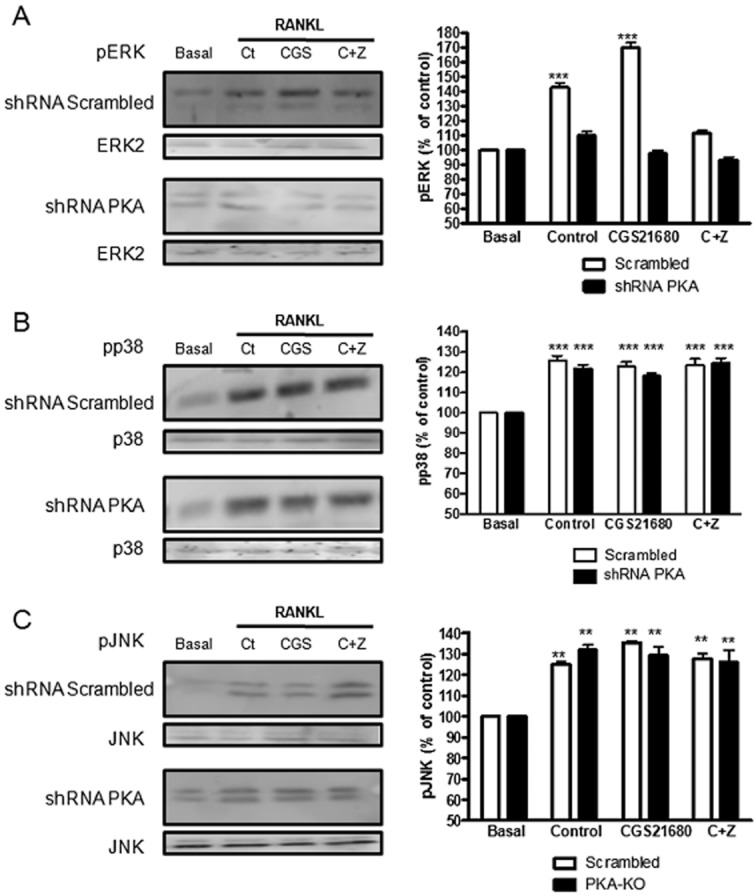

A2AR activation inhibits osteoclast differentiation by activation of ERK1/2

Prior work demonstrates that stimulation of cAMP-PKA signalling lead to activation of the MAPK cascade and activation of ERK1/2, p38 and JNK are well-established signalling intermediates in osteoclast differentiation. For that reason, we studied the involvement of these proteins in the A2AR inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. As observed in Figure 3A, when RAW264.7 cells were incubated with RANKL (Control) we observed an increased in ERK1/2 phosphorylation 10 min after stimulation and this effect was significantly increased in the presence of CGS21680 (170 ± 6% of control for CGS21680 vs. 143 ± 5% of control for control, P < 0.001, n = 4), an effect that was blocked by the A2AR antagonist ZM241385. Thus, as we have previously reported for hepatic stellate cells (Che et al., 2007) ERK1/2 is activated by A2AR and signalling for this activation step proceeds via a PKA-dependent mechanism. Similarly, RANKL activated p38MAPK (125 ± 1% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4), but neither CGS21680 alone nor in the presence of ZM241385 affected this activation (Figure 3B) and there was no effect of PKA knockdown either. Similar to activation of p38MAPK, RANKL stimulation led to JNK activation and A2AR stimulation and PKA knockdown did not affect JNK activation induced by RANKL (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

MAPKs are activated during osteoclast differentiation in a PKA dependent mechanism. RAW264.7 cells were permanently transfected with scrambled or PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA, and treated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z). (A) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was analysed 10 min after stimulation by Western blot. (B) p38 phosphorylation was analysed 10 min after stimulation by Western blot. (C) JNK phosphorylation was analysed 2 h after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with ERK2, p38 or JNK respectively and results normalized appropriately. The results were expressed as the means of four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.5 versus non-stimulated control. In all cases, the y axis has been expanded to show the difference more clearly.

Similar results were obtained in osteoclasts derived from primary BMCs (Supporting Information Figure S1A, Supporting Information Table S1). When BMCs cells were incubated with RANKL (Control), we observed an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation 10 min after stimulation and this effect was significantly increased in the presence of CGS21680 (182 ± 5% of control for CGS21680 vs. 163 ± 9% of control for control, P < 0.001, n = 4), an effect that was blocked by the A2AR antagonist ZM241385. Similarly, RANKL activated p38MAPK and JNK, but neither CGS21680 alone or in the presence of ZM241385 affected this activation.

When we analysed MAPK expression in osteoclasts derived from A2AKO BMCs (Supporting Information Figure S2B, Supporting Information Table S2), we observed that RANKL activated ERK1/2, p38 and JNK in a similar way as RANKL stimulation in wild type cells (195 ± 7%, 158 ± 5%***155 ± 5%*** respectively, P < 0.001, n = 30) and, as expected, CGS21680 (alone or with ZM241385) did not affect activation of these MAPKs.

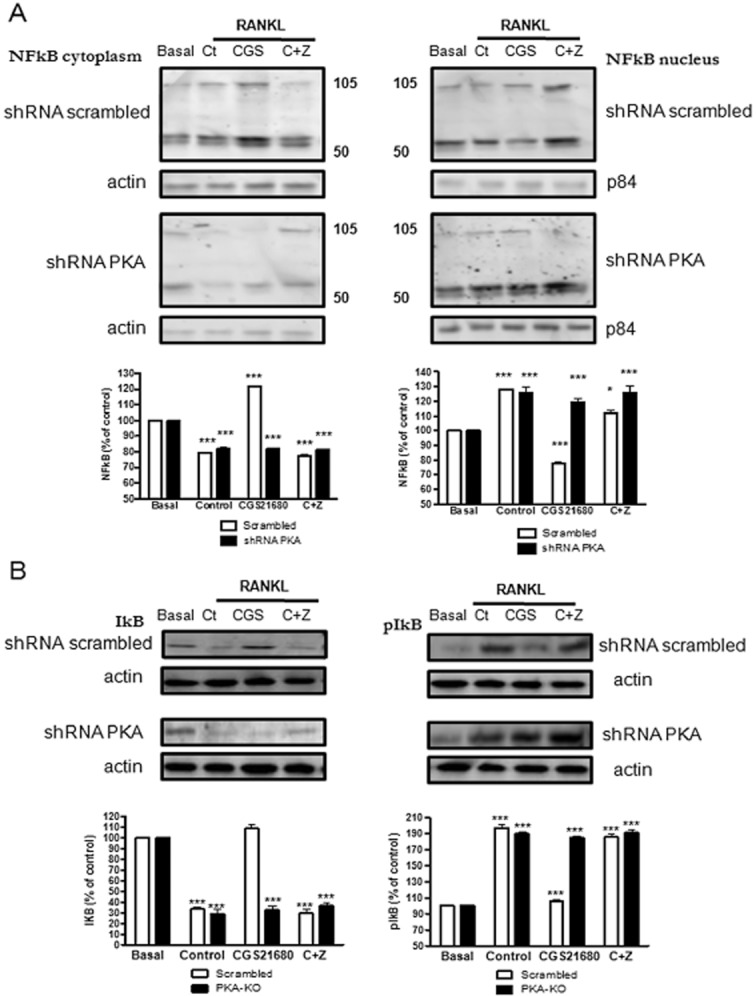

A2AR signals for inhibition of NFκB p50/p105 nuclear translocation via PKA

When RANKL binds to its receptor RANK NFκB is activated and translocated to the nucleus by either the canonical or alternative pathways (Franzoso et al., 1997). In the canonical pathway, phosphorylation of IκB leads to the translocation of the classic NFκB dimer consisting of p50 and p65/RelA, an event required for osteoclast differentiation. We therefore determined the effect of A2AR stimulation on p105/p50 NFκB nuclear translocation. After activation of RAW264.7 cells with RANKL (Control), we observed, as expected, a rapid (15 min) and significant increase in p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation (128.3 ± 0.5% of control, P < 0.5, n = 4), concomitant with a decrease in cytoplasmic p50/p105 NFκB (20.8 ± 0.4% decreased, P < 0.001, n = 4) (Figure 4A). We also found a decrease in cellular IκB alpha (66.7 ± 4% decrease, P < 0.001, n = 4) with an increase in phosphorylated IκB alpha (197.8 ± 7% of control, P < 0.01, n = 4) (Figure 4B) 5 min after stimulation. Treatment with CGS21680 blocked NFκB translocation, with an increase in cytoplasmic p50/p105 NFκB (121.8 ± 1.2% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4), a decrease in nuclear p50/p105 NFκB (22.2 ± 1.2% decreased, P < 0.001 n = 4) (Figure 4A), concomitant with an increase in cellular IκB alpha (108.9 ± 8% activation compared 66.7 ± 4% for control, P < 0.001, n = 4) and a decrease in p-IκB alpha (105.6 ± 6% activation compared 197.8 ± 7% for control, P < 0.001, n = 4) (Figure 4B), all reverted to control when cells were pretreated with ZM241385 1 μM. Moreover, A2A receptor stimulation did not affect NFκB translocation in shRNA PKA cells (118.8 ± 1.9% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4).

Figure 4.

A2A receptor activation inhibits p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in a PKA-dependent mechanism. RAW264.7 cells were permanently transfected with scrambled or PKA catalytic alpha subunit shRNA, and treated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z). (A) p50/p105 NFκB was analysed by Western blot both in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fraction 15 min after stimulation. In data not shown, actin was not found in the nuclear fraction ruling out cytoplasmic contamination of the preparation. (B) IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha were analysed in the cytoplasmic cell fraction 5 min after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with actin in the cytoplasmic fraction and the specific nuclear membrane protein p84 in the nuclear fraction. The results were expressed as the means of four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.5 versus non-stimulated control. In all cases, the y axis has been expanded to show the difference more clearly.

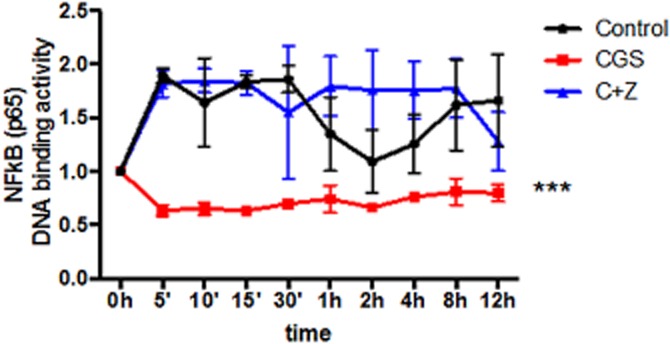

These results correlate with a concomitant decrease in NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity after CGS21680 treatment. NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity increased in the presence of RANKL alone (Control) starting 5 min after stimulation (1.9 ± 0.03 related to 1.0 ± 0 in non stimulated cells, P < 0.001) and was stable up to 30 min after stimulation (Figure 5); CGS21680 inhibited the stimulated increase at 5 min (0.6 ± 0.02 vs. 1.9 ± 0.03 for control, P < 0.001) and at all time points tested (Figure 5). Pretreatment with ZM241385 reversed CGS21680-mediated inhibition of NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity is decreased by activation of the A2AR. RAW264.7 cells were treated with 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z) and NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity was calculated and normalized to non-stimulated control. Activity was measured for up to 12 h and NFκB (p65) transcription factor DNA binding activity is expressed as the mean ± SEM of five different assays. ***P < 0.001, versus non-stimulated control.

Similar results were obtained for osteoclasts derived from primary BMCs (Supporting Information Figure S1C, Supporting Information Table S1). After activation of RAW264.7 cells with RANKL (Control), we observed a rapid (15 min) and significant increase in p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation (130 ± 3% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4), concomitant with a decrease in cytoplasmic p50/p105 NFκB (35 ± 2% decreased, P < 0.001, n = 4) and a decrease in cellular IκB alpha (78 ± 4% decrease, P < 0.001, n = 4) with an increase in phosphorylated IκB alpha (153 ± 4% of control, P < 0.01, n = 4) 5 min after stimulation. Treatment with CGS21680 blocked NFκB translocation, with an increase in cytoplasmic p50/p105 NFκB (110 ± 5% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4), a decrease in nuclear p50/p105 NFκB (14 ± 4% decreased, P < 0.001 n = 4), concomitant with an increase in cellular IκB alpha (107 ± 4% of control, P < 0.001, n = 4) and a decrease in p-IκB alpha (92 ± 3% decreased, P < 0.001, n = 4). All of these changes were abrogated by pretreatment with ZM241385 1 μM.

When we analysed p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in osteoclasts derived from A2AKO BMCs (Supporting Information Figure S2C, Supporting Information Table S2), we observed an increase in p50/p105 NFκB in the nuclear fraction (153 ± 4% for control, 166 ± 8% for CGS21680 and 149 ± 4% for CGS21680 + ZM241385, P < 0.001, n = 3) concomitant with a decrease in the cytoplasmic fraction 15 min after activation (45 ± 5% of control for RANKL, 39 ± 5% of control for CGS21680 and 55 ± 5% of control forCGs21680 + ZM241385, P < 0.001, n = 3).

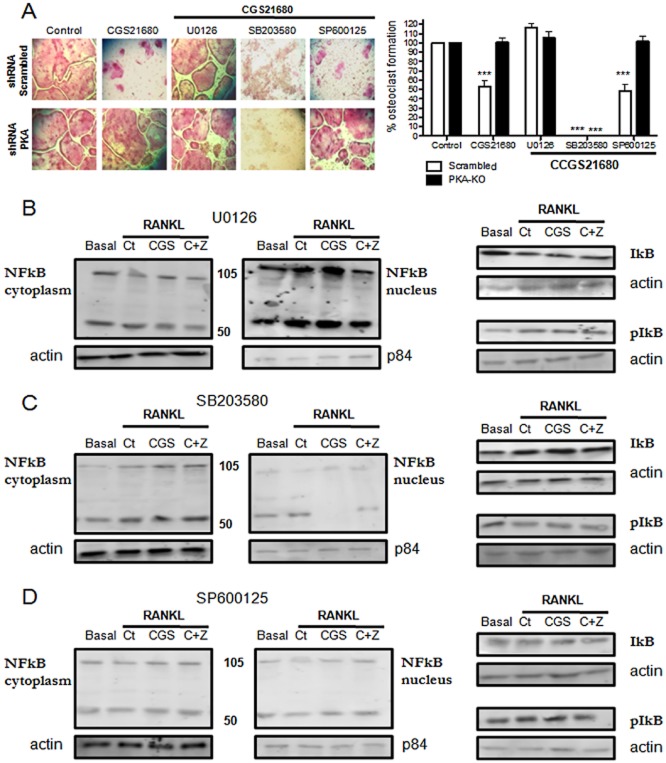

Activation of ERK1/2 by A2AR stimulation mediates inhibition of osteoclast differentiation

To understand if there was a relation between MAPK activation and p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation inhibition by A2AR activation, we studied both osteoclast differentiation by TRAP staining and p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in the presence of several MAPK inhibitors. Inhibition of MEK1/2 with U0126 (10 μM) blocks the A2AR-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by RAW264.7 cells infected with scrambled shRNA without affecting osteoclast differentiation in the shRNA PKA cells (Figure 6A). Interestingly, the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 completely blocked osteoclast differentiation in control and PKA knockdown cells and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 inhibits osteoclast formation in scrambled shRNA infected cells but not in PKA knockdown cells neither diminished osteoclast differentiation nor affected the capacity of A2AR stimulation to diminish osteoclast differentiation (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

A2AR activation inhibits NFκB p50/p105 nuclear translocation by a PKA-ERK1/2 mechanism. (A) PKA catalytic alpha subunit and scrambled silenced RAW264.7-derived osteoclasts were fixed and stained for TRAP after being cultured in the presence of CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of U0126, SB203580 and SP600125 (10 μM each). TRAP-positive cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. The results are expressed as the means of six different assays carried out in duplicate. (B) p50/p105 NFκB expression in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fractions and IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha expression after stimulation in the presence of U0126 10 μM by Western blot in scrambled cells. (C) p50/p105 NFκB expression in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fraction and IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha expression after stimulation in the presence of SB203580 (1 μM) by Western blot in scrambled cells. (D) p50/p105 NFκB expression in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fraction and IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha expression after stimulation in the presence of SP600125 (10 μM) by Western blot in scrambled cells. The results were expressed as the means of four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.5 versus non-stimulated control.

Similar to the effects on osteoclast differentiation, inhibition of ERK1/2 activation by UO126 reversed the effect of A2AR stimulation of NFκB translocation in a PKA-dependent fashion (Figure 6B, Tables 1 and 2). The p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 blocked NFκB translocation, as expected (Figure 6C, Tables 1 and 2) and the JNK inhibitor had no effect on NFκB translocation in cells infected with scrambled shRNA or PKA knockdown cells (Figure 6D, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

NFκB cytoplasmic and nuclear expression and IkB phosphorylation in scrambled cells in the presence of MAPK inhibitors

| Treatment | p50/p105 NFκB cytoplasmic fraction | p50/p105 NFκB nuclear fraction | IκB | p-IκB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U0126 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0%* |

| Control | 79.3 ± 3.4%*** | 130.1 ± 1.6%*** | 86.9 ± 1.1%*** | 109.1 ± 3.9%* |

| CGS21680 | 81.2 ± 4.6%*** | 132.3 ± 2.4%*** | 86.4 ± 0.5%*** | 110.3 ± 0.9%* |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 80.2 ± 5.1%*** | 129.5 ± 1.4%*** | 88.3 ± 1.9%*** | 108.4 ± 4.9%* |

| SB203580 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% |

| Control | 159.3 ± 4.2%*** | 49.5 ± 2.8%*** | 141.2 ± 2.3%** | 74.8 ± 3.3%*** |

| CGS21680 | 168.5 ± 5.5%*** | 44.6 ± 2.2%*** | 165.8 ± 4.4%** | 78.5 ± 6%*** |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 164.1 ± 6.3%*** | 36.3 ± 6.3%*** | 158.1 ± 5.2%** | 79.5 ± 2.9%*** |

| SP600125 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% |

| Control | 90.1 ± 1.1%** | 110.5 ± 3.3%** | 85.6 ± 1%*** | 108.8 ± 1.5%** |

| CGS21680 | 92.1 ± 0.9%* | 106.1 ± 1.6%* | 90.1 ± 5.2%* | 105.3 ± 3.8%* |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 89.4 ± 1.5%** | 110.4 ± 4.4%** | 86.6 ± 3%*** | 109.4 ± 1%** |

Quantification of p50/p105 NFκB cytoplasmic and nuclear signal, IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha signal in the presence of MEK inhibitor U0126, p38 inhibitor SB203580 and JNK inhibitor II (SP600125) 10 μM each in scrambled cells. The results were expressed as the means of four independent experiments.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01

P < 0.5 versus non-stimulated control (basal).

Table 2.

NFκB cytoplasmic and nuclear expression and IkB phosphorylation in PKA catalytic alpha subunit knockdown cells in the presence of MAPK inhibitors

| Treatment | p50/p105 NFκB cytoplasmic fraction | p50/p105 NFκB nuclear fraction | IκB | p-IκB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U0126 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0%*** |

| Control | 74.3 ± 2.14%*** | 142.3 ± 3.1%*** | 83.6 ± 2.1%*** | 129.1 ± 3.9%*** |

| CGS21680 | 76.2 ± 2.9%*** | 139.3 ± 2.9%*** | 85.4 ± 3.5%*** | 131.8 ± 2%*** |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 75.8 ± 2.8%*** | 141.5 ± 2.6%*** | 83.7 ± 1.7%*** | 1308.5 ± 3.8%*** |

| SB203580 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% |

| Control | 144.8 ± 2.3%*** | 69.5 ± 1.3%*** | 115.9 ± 4.1%** | 79.6 ± 1.8%** |

| CGS21680 | 145.6 ± 1.5%*** | 64.8 ± 1.9%*** | 121.5 ± 5.9%*** | 81.8 ± 1.9%*** |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 149.5 ± 3.3%*** | 66.7 ± 0.6%*** | 117.8 ± 3.1%** | 82.3 ± 3.2%** |

| SP600125 | ||||

| Basal | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% |

| Control | 80.3 ± 2%** | 121.5 ± 1.6%*** | 81.5 ± 1%*** | 119.4 ± 0.7%*** |

| CGS21680 | 78.8 ± 1.4%** | 125.6 ± 1.8%*** | 83.1 ± 5.2%** | 121.9 ± 2.4%*** |

| CGS21680 + ZM241385 | 79.3 ± 3.1%** | 129.7 ± 3.2%*** | 79.8 ± 3%*** | 115.9 ± 3.9%** |

Quantification of p50/p105 NFκB cytoplasmic and nuclear signal, IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha signal in the presence of MEK inhibitor U0126, p38 inhibitor SB203580 and JNK inhibitor II (SP600125) 10 μM each in PKA catalytic alpha subunit knockdown cells. The results were expressed as the means of four independent experiments.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01 versus non-stimulated control (basal).

Discussion and conclusions

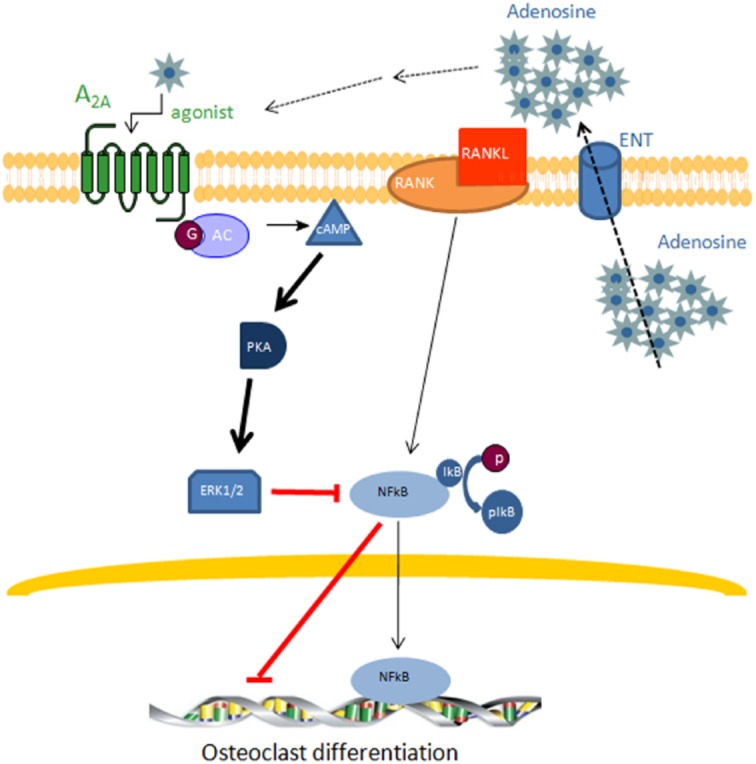

In this work, we have dissected signalling pathways for A2A receptor-mediated regulation of osteoclast differentiation. We found, using both selective knockdowns and pharmacologic stimuli/inhibitors of signalling intermediates, that adenosine A2ARs signal for inhibition of NFκB translocation to the nucleus and inhibit osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism that involves cAMP-PKA-ERK1/2 signalling (Figure 7). In prior, work we have demonstrated that blockade or deletion of adenosine A1Rs diminishes osteoclast differentiation via inhibition of NFκB translocation to the nucleus by a different mechanism, accelerated ubiquitination and proteolysis of TRAF6 and diminished TAK1 signalling (Kara et al., 2010a,b; He and Cronstein, 2012). Thus, adenosine receptor signalling plays a critical role in regulating osteoclast differentiation and the common final pathway for both A1 and A2A receptors is inhibition of NFκB translocation to the nucleus.

Figure 7.

Extracellular adenosine activates adenosine A2AR and inhibits osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation. Adenosine release into the extracellular space by adenosine transporters (ENT) produces an increase in adenosine concentration that activates the adenosine A2AR resulting in an activation of adenylate cyclase and increased cAMP levels which further activate PKA producing ERK1/2 phosphorylation and the concomitant inhibition of p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation. These events result in inhibition of osteoclast differentiation.

Under homeostatic conditions osteoclast differentiation and function is tightly coupled to osteoblasts; osteoblasts express RANKL on their surface and release soluble RANKL which binds to RANK on osteoclast precursors to stimulate their differentiation into osteoclasts. Distal events involved in RANKL-RANK signalling include activation of various MAP kinases including ERK1/2, p38MAPK and JNK, as well as activation and translocation of the NFκB complex to the nucleus where it regulates transcription of genes involved in osteoclast differentiation (Blair et al., 2005). Activation of NFκB is a critical step in osteoclast differentiation and survival. Thus, mice lacking the p50 subunit of NFκB do not generate osteoclasts, and double knockout mice derived from p50 and p52 knockouts have shortened long bones, the incisors fail to erupt into the oral cavity and there are no TRAP+ osteoclasts in bone (Franzoso et al., 1997). In this work, we have demonstrated that stimulation of A2ARs inhibits p50 nuclear translocation, leading to an increase of p50 and its precursor p105 in the cytoplasmic fraction. The cytoplasmic sequestration of p105 is most likely due to diminished phosphorylation of IκB due to A2AR ligation and the subsequent ubiquitination and proteolysis of this chaperone protein. Interestingly, TNFα and IL-1β, two pro-inflammatory cytokines that can act as auxiliary stimuli for osteoclast differentiation, are induced by NFκB and we have previously demonstrated that A2AR stimulation diminishes TNFα and IL-1β secretion; addition of these inflammatory cytokines to the culture reverses the effect of A2AR stimulation on osteoclast generation (Mediero et al., 2012b). It is likely that the inhibition in NFκB nuclear translocation that we observed here forms the link between A2AR and inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. Moreover, this finding may help to explain the inhibition of osteoclast formation and bone resorption in inflammatory diseases resulting from methotrexate therapy, the anti-inflammatory effects of which are mediated by adenosine acting via its receptors (Chan and Cronstein, 2010) in rheumatoid arthritis.

As described above, the involvement of MAPKs in RANKL-RANK activation during osteoclastogenesis is well known (Blair et al., 2005). Among the key regulators of osteoclast differentiation is p38MAPK. Inhibition of p38MAPK activation strongly inhibits osteoclast differentiation not only in co-cultures with osteoblasts, but also in primary bone marrow cultures (Li et al., 2002). Consistent with these in vitro findings, inhibition of p38MAPK diminishes bone loss in animal models of inflammatory arthritis (Bohm et al., 2009). Our results revealed that neither adenosine A2AR stimulation nor blockade of A2AR signalling by PKA catalytic subunit knockdown affected p38MAPK activation but inhibition of p38MAPK by the selective inhibitor SB203580 inhibited NFκB nuclear translocation and osteoclast differentiation. Thus, p38MAPK is not a target for A2AR signalling although activation of this signalling molecule is clearly not sufficient to stimulate osteoclast differentiation in the absence of NFκB signalling.

The role of JNK in osteoclastogenesis has also previously been described (Cheng et al., 2012; Kharkwal et al., 2012). However, as with p38MAPK, intracellular signalling via this protein is secondary in our model; pJNK is activated at late time points (2–4 h) (see Supporting Information Figure S1B) and neither A2AR activation/inhibition nor PKA silencing affected pJNK activation. One explanation for these findings is that both p38 and JNK are constitutively activated in these cells and when ERK signalling is no longer active, JNK and p38 signalling can substitute during osteoclast differentiation (Hotokezaka et al., 2002). Moreover, this hypothesis could explain why CGS21680 does not completely inhibit osteoclast formation. Constitutive activation of p38 may also explain our observation that when ERK1/2 or JNK are inhibited by their specific inhibitors we do not see the expected inhibition in osteoclast differentiation.

Of the three MAPKs studied here, only ERK1/2 is a target for adenosine A2A receptor regulation. Although ERK1/2 plays a role in osteoclast survival (Miyazaki et al., 2000) and differentiation (Saulnier et al., 2012) our results remain controversial because prior reports document that different treatments such as bisphosphonates and statins (Tsubaki et al., 2012) or ormeloxifene (Kharkwal et al., 2012) exert their inhibitory action through inhibition of this MAPK. In contrast, we found that the A2AR ligation both stimulated ERK 1/2 activation and inhibited osteoclast differentiation in a PKA-dependent fashion. The paradoxical role of ERK1/2 in osteoclast differentiation and function has been observed previously. Saulnier et al. observed that deletion of ERK1 diminishes in vitro osteoclastogenesis whereas in these same mice there is an increase in the number of osteoclasts observed in vivo (Saulnier et al., 2012). Saulnier et al. suggested that these observations could be explained by enhanced production of osteoclasts in vivo as compensation for diminished osteoclast function, a hypothesis propounded by He et al. (2011). Nonetheless, we were surprised to find that A2AR stimulation no longer activated ERK1/2 in the absence of PKA (and no longer inhibited osteoclast differentiation either). It has been shown in liver cysts (PC2 defective mice) that cAMP/PKA is able to activate ERK1/2 in a fashion dependent upon activation of Raf/MEK/ERK all of which was inhibited in the presence of a PKA inhibitor (Spirli et al., 2012), and artificial activation of Gαs-AC by forskolin can induce ERK activation through a AC/cAMP/PKA pathway in LβT2 cells (Son et al., 2012).

Our results are clearly consistent with the hypothesis that adenosine A2AR suppresses osteoclast differentiation via GαS-mediated activation of adenylate cyclase/PKA/ERK1/2 signalling for inhibition of NFκB translocation to the nucleus. Nonetheless, the role of adenylate cyclase/cAMP in regulating osteoclast differentiation remains controversial. Recent data suggests that PKA and increased cAMP activate (Kondo et al., 2002) and inhibit osteoclastogenesis and root resorption by odontoclasts (Takada et al., 2004; Yoon et al., 2011). Others reported that although increases in cAMP inhibited osteoclast formation PKA was not involved in this process (Yang et al., 2008). It is difficult to resolve these disparate and contradictory findings and this may reflect differences in the pharmacologic stimuli and inhibitors employed in the different studies.

Moreover, as we have previously reported, CGS21680 does not change NFATc1 mRNA expression during osteoclast differentiation both in scrambled shRNA infected cells and in the shRNA PKA cells (Mediero et al., 2012b). Although we have not directly determined whether CGS21680 directly regulates NFAT phosphorylation/activity, the observation that there is no change in NFATc1 gene expression suggests that we are not likely to find a change in phosphorylation/activity. NFATc1 is induced selectively and potently by RANKL and its activation is mediated by a specific phosphatase, calcineurin, which is activated by calcium/calmodulin signalling following activation of osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR). Our finding that A2A receptor stimulation regulates cellular signalling in a selective manner and the expression of NFATc1 is unaffected by either the A2A agonist or its antagonist supports the hypothesis that A2A receptor activation selectively regulates cellular function and does not act as a general transcriptional inhibitor or cellular toxin.

It is generally accepted that adenosine and its receptors, primarily A2A and A3 receptors, are anti-inflammatory and therefore may be targets for control of inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis (Hasko et al., 2008). Indeed, there is strong evidence that adenosine, generated as a result of methotrexate polyglutamate-mediated inhibition of phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide formyltransferase transformylase mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of methotrexate (Cronstein et al., 1993; Morabito et al., 1998; Montesinos et al., 2003; Chan and Cronstein, 2010). Recent support for the role of A2A receptors in suppression of bone destruction during inflammatory arthritis was provided by Mazzon et al. (2011) who reported that the selective A2AR agonist CGS21680 ameliorates the tissue damage associated with Murine Type II Collagen-induced Arthritis.

In conclusion, adenosine, acting at A2AR, inhibits osteoclast differentiation and regulates bone turnover via activation of PKA and inhibition of NFκB nuclear translocation, observations that suggest a mechanism by which adenosine mediates the anti-inflammatory effects to inhibit bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR56672, AR56672S1, AR54897, AR046121), the NYU-HHC Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR000038), the NYUCI Center Support Grant, 9NIH/NCI 5 P30CA16087-310 and grants from OSI, Takeda and Gilead Pharmaceuticals.

Glossary

- A2AR

adenosine A2A receptor

- C + Z

CGS21680 + ZM241385

- shRNA PKA

shRNA against PKA catalytic alpha subunit

Conflicts of interest

AM and BNC have filed a patent on use of adenosine A2AR agonists to prevent prosthesis loosening (pending). MP-A does not have any disclosures. BNC holds patents numbers 5 932 558; 6 020 321; 6 555 545; 7 795 427; adenosine A1R and A2BR antagonists to treat fatty liver (pending); adenosine A2AR agonists to prevent prosthesis loosening (pending). BNC is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, CanFite Biopharmaceuticals, Cypress Laboratories, Regeneron (Westat, DSMB), Endocyte, Protalex, Allos, Inc., Savient, Gismo Therapeutics, Antares Pharmaceutical, Medivector, King Pharmaceutical, Celizome, Tap Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Sepracor, Amgen, Combinatorx, Kyowa Hakka, Hoffman-LaRoche and Avidimer Therapeutics. BNC has stock in CanFite Biopharmaceuticlas.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 A2A receptor activation promotes ERK1/2 phosphorylation and inhibits p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in primary BMCs cells. Primary BMCs cells were treated with 50 ng·mL−1 M'CSF and 50 ng·mL−1 RANKL together with CGS21680 1 μM (CGS) alone or in the presence of ZM241385 1 μM (C + Z). (A) ERK1/2, p38 and JNK phosphorylation was analysed 10 min or 2 h after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with ERK2, p38 or JNK respectively and results normalized appropriately. (B) JNK time course activation. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with JNK and results normalized appropriately. (C) p50/p105 NFκB was analysed by Western blot both in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fraction 15 min after stimulation. IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha were analysed in the cytoplasmic cell fraction 5 min after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with actin in the cytoplasmic fraction and the specific nuclear membrane protein p84 in the nuclear fraction.

Figure S2 Effects of CGS21680 in relation to PKA activity, ERK1/2 phosphorylation and p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation are lost in A2AKO mice. (A) PKA activity was calculated 15 min after RAW264.7 cells stimulation. Gel image reflect separation of phosphorylated/non-phosphorylated peptide migration. Data were express as the mean ± SEM in units/2.5 × 106 cells considering the relation of phosphorylated Peptide A1 and PKA activity according to manufacturer's indication (n = 3). + indicate positive control and – indicate negative control. (B) ERK1/2, p38 and JNK phosphorylation was analysed 10 min after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were reprobed with ERK2, p38 or JNK respectively and results normalized appropriately. (C) p50/p105 NFκB was analysed by Western blot both in the cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fraction 15 min after stimulation. IκB alpha and p-IκB alpha were analysed in the cytoplasmic cell fraction 5 min after stimulation by Western blot. To normalize for protein loading, the membranes were re-probed with actin in the cytoplasmic fraction and the specific nuclear membrane protein p84 in the nuclear fraction.

Table S1 A2A receptor activation promotes ERK1/2 phosphorylation and inhibits p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation in primary BMCs cells.

Table S2 Effects of CGS21680 in relation to ERK1/2 phosphorylation and p50/p105 NFκB nuclear translocation are lost in A2AKO mice.

References

- Blair HC, Robinson LJ, Zaidi M. Osteoclast signalling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:728–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm C, Hayer S, Kilian A, Zaiss MM, Finger S, Hess A, et al. The alpha-isoform of p38 MAPK specifically regulates arthritic bone loss. J Immunol. 2009;183:5938–5947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce BF, Yao Z, Xing L. Osteoclasts have multiple roles in bone in addition to bone resorption. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19:171–180. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i3.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Calker D, Muller M, Hamprecht B. Adenosine regulates via two different types of receptors, the accumulation of cyclic AMP in cultured brain cells. J Neurochem. 1979;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Methotrexate – how does it really work? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:175–178. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates collagen expression by hepatic stellate cells via pathways involving protein kinase A, Src, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling cascade or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1626–1636. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Huang Z, Ma J, Zhu J, Moratalla R, Standaert D, et al. A(2A) adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9192–9200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B, Li J, Du J, Lv X, Weng L, Ling C. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits osteoclastogenesis by modulating NF-kappaB and MAPKs pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronstein BN, Naime D, Ostad E. The antiinflammatory mechanism of methotrexate. Increased adenosine release at inflamed sites diminishes leukocyte accumulation in an in vivo model of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2675–2682. doi: 10.1172/JCI116884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoso G, Carlson L, Xing L, Poljak L, Shores EW, Brown KD, et al. Requirement for NF-kappaB in osteoclast and B-cell development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3482–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Irenius E, Kull B, Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors – an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A1 receptor regulates osteoclast formation by altering TRAF6/TAK1 signaling. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9292-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Staser K, Rhodes SD, Liu Y, Wu X, Park SJ, et al. Erk1 positively regulates osteoclast differentiation and bone resorptive activity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano D, Aoki Y, Ogasawara H, Kodama H, Waga I, Sakanaka C, et al. Functional coupling of adenosine A2a receptor to inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem J. 1996;316(Pt 1):81–86. doi: 10.1042/bj3160081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K, Taki H, Shinoda K, Hounoki H, Miyahara T, Tobe K, et al. Inhibition of tumor progression locus 2 protein kinase suppresses receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis through down-regulation of the c-Fos and nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 genes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:133–137. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotokezaka H, Sakai E, Kanaoka K, Saito K, Matsuo K, Kitaura H, et al. U0126 and PD98059, specific inhibitors of MEK, accelerate differentiation of RAW264.7 cells into osteoclast-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47366–47372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara FM, Chitu V, Sloane J, Axelrod M, Fredholm BB, Stanley ER, et al. Adenosine A1 receptors (A1Rs) play a critical role in osteoclast formation and function. FASEB J. 2010a;24:2325–2333. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara FM, Doty SB, Boskey A, Goldring S, Zaidi M, Fredholm BB, et al. Adenosine A(1) receptors regulate bone resorption in mice: adenosine A(1) receptor blockade or deletion increases bone density and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss in adenosine A(1) receptor-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010b;62:534–541. doi: 10.1002/art.27219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkwal G, Chandra V, Fatima I, Dwivedi A. Ormeloxifene inhibits osteoclast differentiation in parallel to downregulating RANKL-induced ROS generation and suppressing the activation of ERK and JNK in murine RAW264.7 cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48:261–270. doi: 10.1530/JME-11-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Guo J, Bringhurst FR. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate/protein kinase A mediates parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor regulation of osteoclastogenesis and expression of RANKL and osteoprotegerin mRNAs by marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1667–1679. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Udagawa N, Itoh K, Suda K, Murase Y, Nishihara T, et al. p38 MAPK-mediated signals are required for inducing osteoclast differentiation but not for osteoclast function. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3105–3113. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londos C, Cooper DM, Wolff J. Subclasses of external adenosine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:2551–2554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzon E, Esposito E, Impellizzeri D, DI Paola R, Melani A, Bramanti P, et al. CGS 21680, an agonist of the adenosine (A2A) receptor, reduces progression of murine type II collagen-induced arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2119–2129. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediero A, Frenkel SR, Wilder T, He W, Mazumder A, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor activation prevents wear particle-induced osteolysis. Sci Transl Med. 2012a;4:135ra165. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediero A, Kara FM, Wilder T, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A(2A) receptor ligation inhibits osteoclast formation. Am J Pathol. 2012b;180:775–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JT, Shen C, Schreibman D, Coffey D, Zakharenko O, Fisher R, et al. Adenosine A1 receptor promotion of multinucleated giant cell formation by human monocytes: a mechanism for methotrexate-induced nodulosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1308–1315. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199707)40:7<1308::AID-ART16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T, Katagiri H, Kanegae Y, Takayanagi H, Sawada Y, Yamamoto A, et al. Reciprocal role of ERK and NF-kappaB pathways in survival and activation of osteoclasts. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:333–342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos MC, Desai A, Delano D, Chen JF, Fink JS, Jacobson MA, et al. Adenosine A2A or A3 receptors are required for inhibition of inflammation by methotrexate and its analog MX-68. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:240–247. doi: 10.1002/art.10712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito L, Montesinos MC, Schreibman DM, Balter L, Thompson LF, Resta R, et al. Methotrexate and sulfasalazine promote adenosine release by a mechanism that requires ecto-5'-nucleotidase-mediated conversion of adenine nucleotides. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:295–300. doi: 10.1172/JCI1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier N, Guihard S, Holy X, Decembre E, Jurdic P, Clay D, et al. ERK1 regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niches. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte G, Fredholm BB. Signalling from adenosine receptors to mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cell Signal. 2003;15:813–827. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexl V, Mancusi G, Holler C, Gloria-Maercker E, Schutz W, Freissmuth M. Stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase via the A2A-adenosine receptor in primary human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5792–5799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son YL, Ubuka T, Millar RP, Kanasaki H, Tsutsui K. Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone inhibits GnRH-induced gonadotropin subunit gene transcriptions by inhibiting AC/cAMP/PKA-dependent ERK pathway in LbetaT2 cells. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2332–2343. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirli C, Morell CM, Locatelli L, Okolicsanyi S, Ferrero C, Kim AK, et al. Cyclic AMP/PKA-dependent paradoxical activation of Raf/MEK/ERK signaling in polycystin-2 defective mice treated with sorafenib. Hepatology. 2012;31:25872. doi: 10.1002/hep.25872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Takada K, Kajiya H, Fukushima H, Okamoto F, Motokawa W, Okabe K. Calcitonin in human odontoclasts regulates root resorption activity via protein kinase A. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:12–18. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubaki M, Satou T, Itoh T, Imano M, Yanae M, Kato C, et al. Bisphosphonate- and statin-induced enhancement of OPG expression and inhibition of CD9, M-CSF, and RANKL expressions via inhibition of the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway and activation of p38MAPK in mouse bone marrow stromal cell line ST2. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;631:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen HK, Zhao H, Mulari M, Halleen JM. The cell biology of osteoclast function. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 3):377–381. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzijl D, Ijzerman AP. Functional selectivity of adenosine receptor ligands. Purinergic Signal. 2011;7:171–192. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Wang MW, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Interleukin-4 reversibly inhibits osteoclastogenesis via inhibition of NF-kappa B and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6622–6630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DC, Tsay HJ, Lin SY, Chiou SH, Li MJ, Chang TJ, et al. cAMP/PKA regulates osteogenesis, adipogenesis and ratio of RANKL/OPG mRNA expression in mesenchymal stem cells by suppressing leptin. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Goto M, et al. A novel molecular mechanism modulating osteoclast differentiation and function. Bone. 1999;25:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Ryu JY, Lee Y, Lee ZH, Kim HH. Adenylate cyclase and calmodulin-dependent kinase have opposite effects on osteoclastogenesis by regulating the PKA-NFATc1 pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1217–1229. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.