Abstract

A 58-year-old man was re-admitted to the Urology service with delayed gross hematuria and unstable he-modynamics, following a percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) procedure performed for an obstructive solitary left lower calyceal stone. A selective left renal angiogram demonstrated an interpolar arteriovenous fistula (AVF), which was treated with successful coil embolization of a sub-segmental feeding branch. Sub-sequent nephrostogram confirmed a coexisting caliceovenous fistula, which was observed and healed spon-taneously. Iatrogenic coexisting intrarenal AVF and caliceovenous fistulae have never been reported and should be considered as a possible cause of delayed severe hematuria with unstable hemodynamics, and/or increase in baseline creatinine after PCNL.

Keywords: caliceovenous fistula, coil embolization, intrarenal artriovenous fistula (AVF), percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), renal angiogram

Introduction

Delayed hematuria occurs in approximately 1% of all percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) patients and is almost always secondary to pseudoaneurysms or interpolar arteriovenous fistula (AVF) [1, 2]. Significant venous injuries during PCNL are under-diagnosed, and most of these lesions are not detected even on angiography [1, 2]. Iatrogenic intraoperative renal pelvis and calyceal perforation often occurs during percutaneous tract dilation. It is important to note that caliceovenous fistula may be missed or cannot be accurately determined by cross sectional imaging [3]. Additionally, when intrapelvic pressure exceeds the systemic venous pressure, as happens in an obstructed kidney, it may cause backflow of urine into the patient’s circulation via spontaneously developed veno-caliceal fistula and, in rare circumstances, can increase the serum creatinine level or present as pseudo renal failure [3]. We review the current literature and report an index case of coexisting intrarenal AVF and caliceovenous fistulae, visualized on angiography and nephrostogram, respectively, after PCNL.

Case Report

A 58-year-old man, presented to our service with delayed hematuria, following a PCNL procedure, performed for an obstructive solitary left lower calyceal stone. During the PCNL procedure, an upper polar calyceal access was successfully obtained to get direct access to stone. The access tract was dilated to 30 French using a NephroMax, balloon (Boston Scientific). The stone measuring 1.1 × 0.7 × 0.5 cm was removed intact, and the patient was discharged on post-operative day 2.

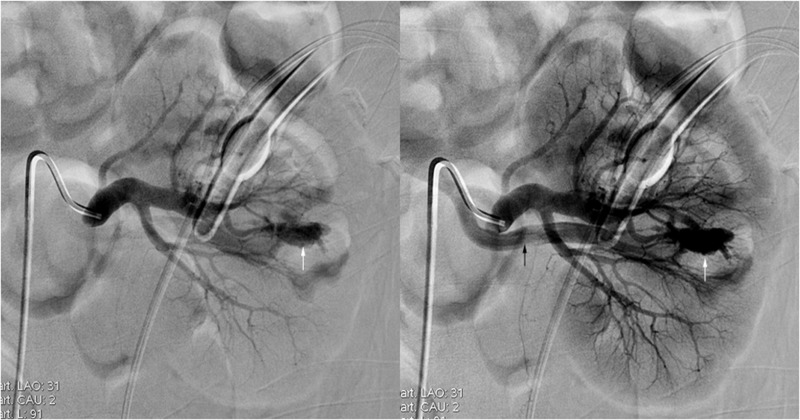

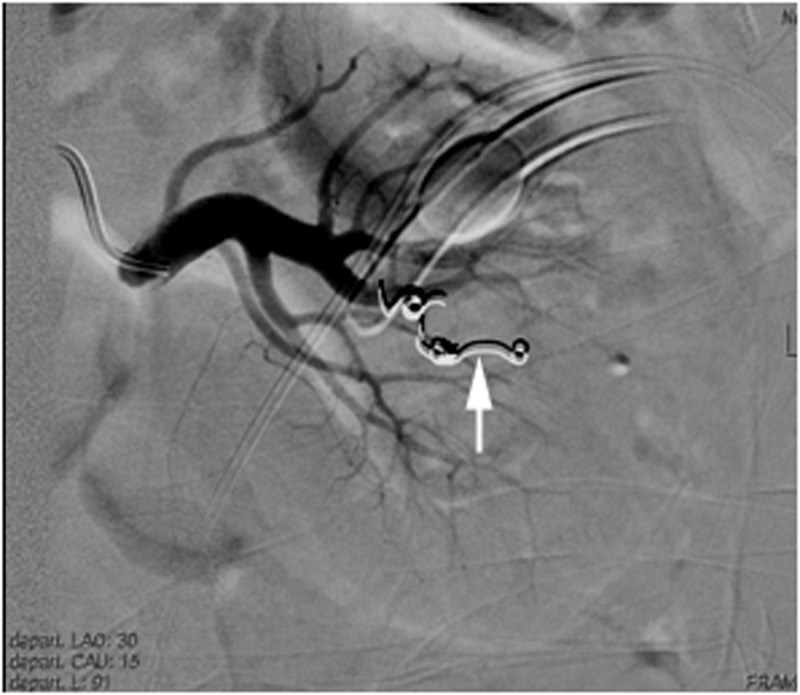

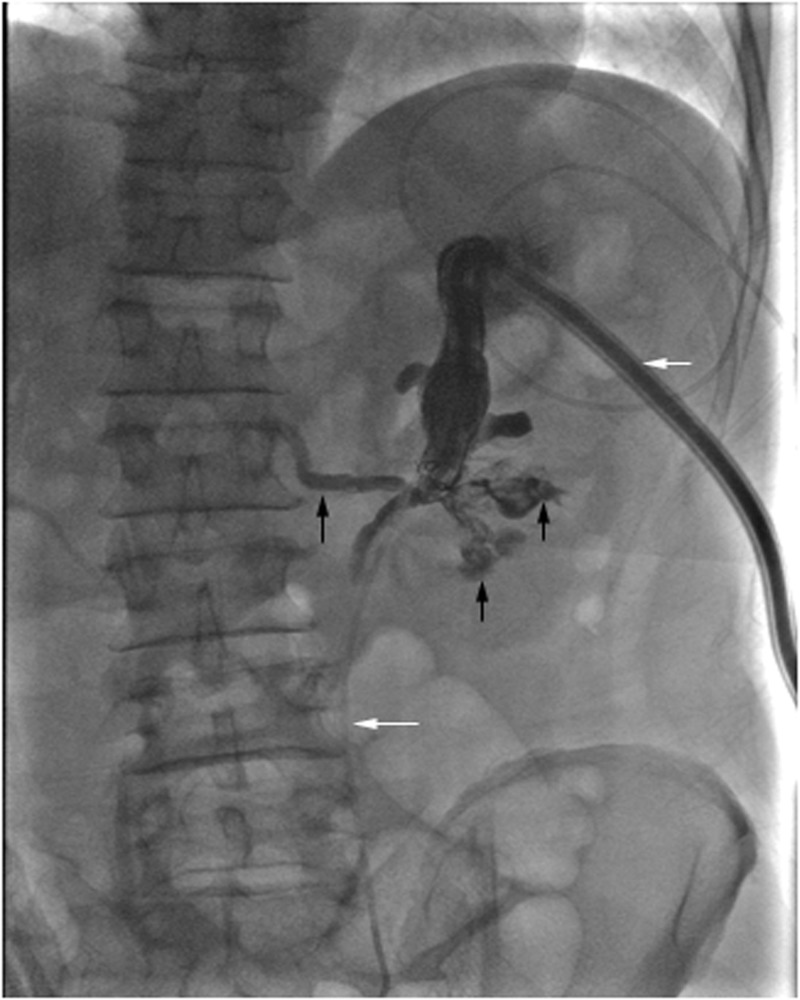

On post-op day 8, the patient developed gross hematuria and was therefore re-admitted with unstable hemodynamics (heart rate: >100/min and systolic BP: <100 mmHg). Selective left renal angiogram demonstrated early visualization of a segmental interpolar draining vein, consistent with an iatrogenic AVF (Fig. 1). Successful embolization of the segmental branch feeding the AVF was performed using one, 3 mm × 2.5 mm Vortex coil (Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland), and two, 4 mm × 2 mm Tornado coils (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) (Fig. 2). Subsequent nephrostogram demonstrated immediate filling of posterior segmental vein draining into the left renal vein with residual clots in the intrarenal collecting system but without perinephric extravasation and drainage of contrast into the ureter (Fig. 3). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of a coexisting caliceovenous fistula. Having performed successful embolization of the AVF, it was decided to leave the nephrostomy tube in situ. Hematuria stopped completely within next 4 h.

Fig. 1.

A 58-year-old man presented with delayed hematuria following 2-stage PCNL. A selective left renal angiogram demonstrates an inter-polar AVF (white arrows) with early visualization of segmental vein (black arrow)

Fig. 2.

Selective left renal angiogram demonstrates successful coil embolization (white arrow) of a sub-segmental branch feeding the AVF

Fig. 3.

Nephrostogram following embolization of an AVF demonstrates nephrostomy catheter (short white arrow) and ureteral stent (long white arrow) positions in the upper pole calyx and ureter, respectively. Visualization of the residual clots in the renal pelvis and calyces (short black arrows), and immediate filling of posterior segmental vein (long black arrow), consistent with findings of coexisting caliceovenous fistula

A follow-up nephrostogram after 48 h demonstrated free drainage of contrast into the ureter without filling of the renal vein (Fig. 4). Nephrostomy tube removal was performed. Hematocrit and creatinine values improved from 18.2%, and 1.39 mg% pre-procedurally, to 26.2% and 0.9 mg% (patient’s baseline value), respectively.

Fig. 4.

A follow-up nephrostogram 48 h later shows no opacification of the renal vein, consistent with the healing of the caliceovenous fistula

Discussion

Recently, the PCNL technique decreased tract related morbidity by limiting the sheath to a size small enough to accommodate a standard rigid nephroscope (19.5–26 French) [4]. Additionally, mini PCNL can be performed with a tract size of 16–20 French [4]. Richstone et al. demonstrated the frequency of postoperative hemorrhage following percutaneous renal interventions [2]. Fifty-seven out of 4695 patients (1.2%) required selective angioembolization (44 PCNL and 13 others). Angiography revealed treatable lesions in 94.7% of patients. Srivastava et al. specifically analyzed vascular complications after single-stage PCNL [1]. All the renal punctures were performed using the bull’s eye technique. Twenty-seven out of 1854 patients had significant bleeding after PCNL. On angiography, the offending lesion was successfully embolized in 24 cases. No lesion was found in 3 cases. Clearly, with segmental and interlobar arteries and veins in close approximation, multiple injuries can occur [1, 2]. In Richstone et al. series, 10/57 patients had >1 angiographic finding. Srivastava et al. reported combined pseudoaneurysm and AVF in 4 out of 27 cases. However, no patient in any of the above studies had a coexisting caliceovenous fistula but learning point is that failure to identify multiple lesions at angiography and or serial imaging can lead to embolization failures.

Chan et al. reported first case of veno-caliceal fistula confirmed on imaging that developed non-iatrogenically due to high intrapelvic pressure secondary to stricture of a graft ureter in a renal allograft recipient [3]. The renal graft biopsy was negative for rejection. Despite the negative scintigraphy finding, and in view of rapid increase in creatinine from baseline value of 2.1 mg% to 10.5 mg% at 3 months post-transplantation, percutaneous drainage of the graft kidney was performed. Antegrade pyelogram demonstrated a prominent renal pelvis, simultaneous opacification of the transplant renal vein without visualization of the graft ureter. Follow-up nephrostogram at 2 weeks after ureteric re-implantation demonstrated free flow of contrast into the bladder, spontaneous closure of veno-caliceal fistula, and stabilization of serum creatinine to 1.6 mg%. This confirmed pseudo renal failure as the cause of persistently increased serum creatinine levels in the setting of normal scintigraphic findings. Geara et al. reported the first documented case of pyelovenous backflow during antegrade pyelogram [5]. The patient presented with left sided hydronephrosis and pyelonephritis secondary to an obstructing ureteral stone. Antegrade pyelogram performed during left nephrostomy tube placement demonstrated flow of contrast into the left renal vein. Contrary to the non-iatrogenic development of veno-caliceal fistula or pyelovenous backflow as reported above, our case developed AVF, as well as, a caliceovenous fistula due to inadvertent injuries to sub-segmental artery, vein and an interpolar calyx likely from (1) multiple percutaneous renal punctures in order to obtain direct access to stone (2) tract dilation to size 30 French, and (3) frequent manipulation of endourological instruments in a tight renal pelvis.

Of note, Srivastava et al. found no significant change in the serum creatinine values after PCNL and after targeted embolization (1.58 ± 0.72 mg% versus 1.68 ± 0.67 mg%, P> 0.05). However, Chan et al. demonstrated recirculation of creatinine via a non-traumatic veno-caliceal fistula, in the setting of non-obstructive scintigraphic findings presenting as pseudo renal failure. Additionally, only 30% of AVFs become symptomatic but 70% of them resolve spontaneously within 1–2 years [6]. Symptomatic AVFs can result in persistent hematuria and renal transplant dysfunction due to significant arteriovenous shunting secondary to “intrarenal steal phenomenon” [6]. It is likely that the coexisting AVF and iatrogenic caliceovenous fistula caused recirculation of urine into our patient’s blood, resulting in rise of serum creatinine.

Contrary to arterial bleeding, intraoperative renal pelvis perforation (3.4%) and calyceal perforation, which often occurs with tract dilation and venous bleeding secondary to caliceovenous communication, are usually not so severe and are generally self-limiting [1, 2, 7]. Within 24–48 h, the urothelium heals, provided that the collecting system is adequately drained [8]. Rise in creatinine with persistent delayed hematuria should, however, raise a red flag, especially when associated with residual stone fragments or clots from coexisting AVF as happened in our case causing intermittent obstruction to urinary flow, and resultant rise in intrarenal collecting system pressure responsible for recirculation of urine into the venous tree. It is likely that chances of coexisting fistulae in our case could have been decreased by sound anatomic knowledge, using a precise initial posterolateral puncture, preferably with a bull’s eye technique, graduated and limited tract dilatation (26 French or less), and choosing a pediatric nephroscope due to unfavorable collecting system anatomy (non-capacious intrarenal pelvis). Additionally, the decision to allow caliceovenous fistula to heal spontaneously was justified by (1) complete clearance of stone/calyceal obstruction and (2) disappearance of flow to intrarenal AVF intraprocedurally, and (3) residual blood clots in the pelvicalyceal system will lyse spontaneously because of the endogenous urokinase, thus allowing normalization of the pressures in the intrarenal vascular tree and intrarenal collecting system.

Conclusions

In summary, coexisting intrarenal AVF and caliceovenous fistula should be considered as a possible cause of delayed severe hematuria after PCNL. Based on this case, it appears reasonable to allow the caliceovenous fistula to heal spontaneously following traditional successful embolization of the intrarenal AVF.

Funding Statement

Funding sources. The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests. The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Neeraj Rastogi, Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA.

Walter Zawacki, Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA.

Herlen Alencar, Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Srivastava A, Singh KJ, Suri A, Dubey D, Kumar A, Kapoor R, Mandhani A, Jain S. Vascular complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: are there any predictive factors? Urology. 2005 Jul;66(1):38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richstone L, Reggio E, Ost MC, Seideman C, Fossett LK, Okeke Z, Rastinehad AR, Lobko I, Siegel DN, Smith AD. First Prize (tie): Hemorrhage following percutaneous renal surgery: characterization of angiographic findings. J Endourol. 2008 Jun;22(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan YH, Wong KM, Kwok PC, Liu AY, Choi KS, Chau KF, Li CS. A veno-caliceal fistula related to ureteric stricture in a kidney allograft masquerading as renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007 Apr;49(4):547–551. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai MR, Sharma R, Mishra S, Sabnis RB, Stief C, Bader M. Single-step percutaneous nephrolithotomy (microperc): the initial clinical report. J Urol. 2011 Jul;186(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geara A, Kamal L, El-Imad B, El-Sayegh S. Visualization of the renal vein during pyelography after nephrostomy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010 Mar 23;4:93–000. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi K, Censullo ML, Rossman LL, Kyriakides PN, Kahan BD, Cohen AM. Interventional radiologic management of renal transplant dysfunction: indications, limitations, and technical considerations. Radiographics. 2007 Jul-Aug;27(4):1109–1130. doi: 10.1148/rg.274065135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Rosette J, Assimos D, Desai M, Gutierrez J, Lingeman J, Scarpa R, Tefekli A, CROES PCNL Study Group The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Global Study: indications, complications, and outcomes in 5803 patients. J Endourol. 2011 Jan;25(1):11–17. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michael III, G . Percutaneous Endourology Treatment & Management 2011; http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/446934-treatment