Abstract

A variety of minimally-invasive approaches for aortic valve replacement (AVR) have been developed and are increasingly being utilized. The different approaches described, such as partial upper sternotomy, right parasternal thoracotomy or transverse sternotomy have the aim to decrease invasiveness and reduce surgical trauma. Whereas port access surgery with remote cannulation has the attendant risks inherent with peripheral cardiopulmonary bypass and limitations in terms of myocardial protection and adequate cardiac dearing, partial sternotomies or thoracotomies may be associated with suboptimal chest wall reconstruction. Here described is a technique of minimal-access aortic valve replacement, which entails limited skin incision and full median sternotomy. Advantages of the present approach include a superior cosmetic result, when compared to standard sternotomy incision, and the safety of the midline access, which may be immediately converted into standard approach, in case of need, and is associated with stable chest wall reconstruction. Selective indications and outcome of minimal-access AVR are discussed.

KEYWORDS : Aortic valve replacement (AVR), sternotomy, thoracotomy, port-access, minimally invasive surgery

Introduction

Conventional aortic valve replacement (AVR) via complete median sternotomy is a safe and feasible procedure with low risk for patients providing excellent long-term outcome (1,2). Over the last two decades, different minimally-invasive approaches for AVR have been developed and are increasingly being utilized. There are different approaches described, such as partial upper sternotomy, right parasternal thoracotomy or transverse sternotomy. All these approaches have the aim to decrease invasiveness and reduce surgical trauma. Advantages of minimal invasive AVR have been shown as less postoperative pain, shorter ICU and hospital stays, shorter ventilation time, decreased blood loss and better cosmetic results with mortality and morbidity comparable to conventional sternotomy (3).

Indications

In patients with multiple extra-cardiac co-morbidities minimally invasive approaches may increase the overall operative risk, because longer cross clamp-, bypass- and surgery times compared to conventional AVR have been described. However, these patients may still request surgery with favourable cosmetic outcome. We describe a technique of minimal-access AVR, which combines a minimal skin incision (range, 7.0-9.0 cm) with the surgical advantages and the safety of full median sternotomy (clear arrangement, easy access to the operation field and shorter operation time).

Technique & technology

The patient is placed in the supine position, as for a standard median sternotomy. A midline skin incision is started 2-3 cm below the sternal angle (or angle of Louis) and is extended to a maximum length of 9 cm. An additional 1-1.5 cm skin incision is made 2 cm below the xiphoid process (Figure 1). The soft tissues over the body of the sternum and manubrium are undermined to expose the suprasternal notch and the xiphoid process. A complete median sternotomy is performed using an oscillating saw, starting from the body of the sternum and extending above and below the sternum during alternate retraction of the soft tissue flap. A Finocchietto chest retractor is inserted and the thymic fat is removed. The pericardium is entered through an asymmetrical vertical incision, and traction sutures are placed on the free edges to improve exposure of the right atrial appendage and the inter-atrial groove.

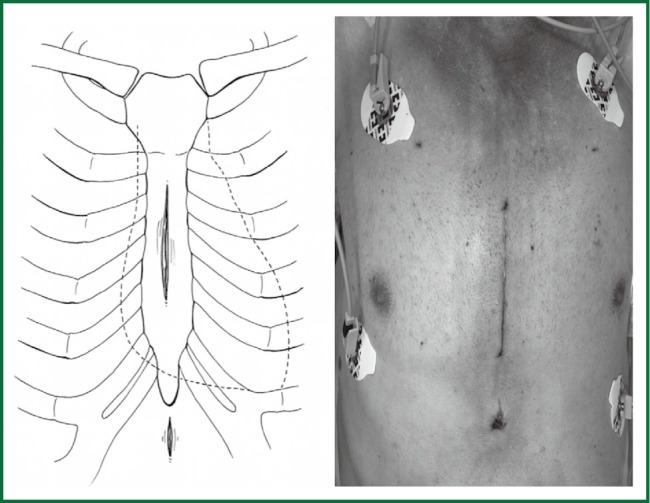

Figure 1.

The cartoon and the photo show the length and position, relative to sternum and cardiovascular structures, of the midline skin incisions. A complete median sternotomy is performed through the main skin incision (7 cm) using an oscillating saw, starting from the body of the sternum and extending above and below the sternum during alternate retraction of the soft tissue flap. The venous cannula is tunnelled via the small (1.5 cm) subxiphoid skin incision, through which the mediastinal tube will be placed at the end of the procedure.

A purse-string suture for arterial cannulation is placed in the distal portion of the ascending aorta, and another is positioned on the right atrial free wall below the atrial appendage for venous cannulation.

The aorta is cannulated using a 22 F or 24 F (according to body surface area) wire-reinforced femoral arterial cannula (Medtronic, Inc., Medtronic DLP; Grand Rapids, MI, U.S.A.). This cannula is chosen for its small size, so that it can be introduced directly through the primary incision (or by Seldinger technique), and for its flexibility, because it can conform easily to the soft-tissue flap at the upper end of the wound. In addition, the cannula is equipped with an obturator-dilator, which allows prompt insertion into less accessible portions of the ascending aorta.

Venous cannulation is performed with a right-angled, 28-F cannula (Medtronic, Inc., Medtronic DLP; Grand Rapids, MI, U.S.A.). With the tip protected by a glove, the cannula is tunnelled through the sub-xiphoid skin incision and inserted perpendicular to the right atrial free wall to ensure unimpeded venous drainage (Figure 2).

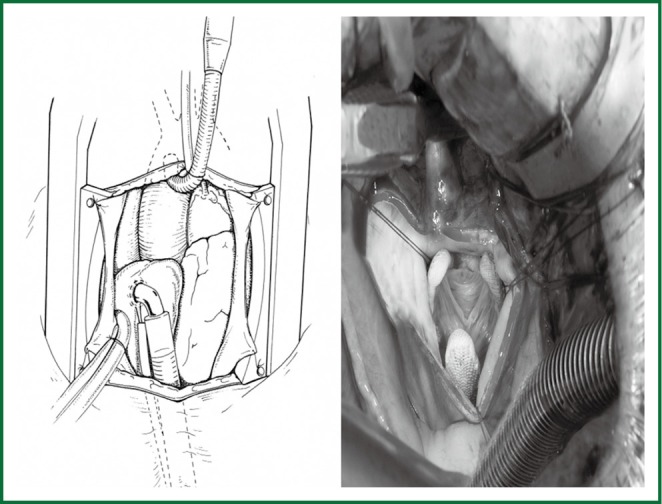

Figure 2.

Arterial cannulation is performed using a 22-F wire reinforced flexible femoral artery cannula and venous cannulation using a right-angled 28-F cannula. With the tip protected by a glove, the cannula is advanced through the subxiphoid skin incision and inserted perpendicular to the right atrial free wall to ensure unimpeded venous drainage. A left atrial vent line is inserted via the right superior pulmonary vein. A transverse (near) circumferential aortotomy is performed to improve exposure of the aortic root.

Normothermic bypass is begun, and a vent line is positioned through the right superior pulmonary vein. After the heart is emptied, the right atrium is retracted cephalad and a coronary sinus catheter is inserted, with transesophageal echocardiographic guidance, for retrograde delivery of cardioplegic solution.

The aortic cross-clamp is applied through the main incision (alternatively, a flexible aortic clamp can further improve exposure) and the heart is arrested by means of retrograde cardioplegia. After 1/3 of the cardioplegia dose is administered, a transverse (near-circumferential) aortotomy is performed to improve exposure of the aortic root and the remaining 2/3 of cardioplegic solution is injected antegrade directly into the coronary ostia.

AVR is then performed as it would be in the case of a standard median sternotomy. Maintenance cardioplegic solution is administered through the coronary sinus. After repair of the aortotomy, de-airing is performed via the ascending aorta and vent line. The adequacy of de-airing is evaluated by transesophageal echocardiography. Cardioversion is achieved by direct application of pediatric paddles.

The cannulae are then removed, after which a pericardial chest tube is inserted through the sub-xiphoid skin incision. The sternotomy is closed with stainless steel wires, and the soft tissue is closed with running absorbable suture (4,5).

Outcomes

Patients are extubated either in the operating room or shortly thereafter in the recovery room. After 12 hours of intensive care unit observation, they are admitted to the regular ward, and discharge from the hospital is usually planned on 5th postoperative day, in low risk patients. This technique has been applied to isolated aortic valve disease, where extra-cardiac co-morbidities suggested to avoid partial sternotomy or thoracotomy or when an improved cosmetic result was strongly requested. A similar technique has also been applied in children and adults for repair of simple congenital septal defects. No intraoperative conversion to full sternotomy skin incision has been necessary in any of the patients.

Concerns and controversies

Over the last two decades several minimally invasive approaches to aortic valve surgery, such as partial upper sternotomy, right parasternal thoracotomy or transverse sternotomy have been increasingly used.

The general hypothesis underlying these techniques is that smaller incisions and limited dissection may attenuate intraoperative trauma and complications, thereby hastening postoperative recovery and minimizing procedure-related costs. In addition, patient satisfaction may increase in association with smaller surgical scars and more rapid recovery. However, in randomized controlled trials as well as meta-analysis for mortality, no statistically significant differences have been seen between patients receiving conventional or minimally invasive AVR (6,7).

Aortic valve surgery by a right parasternal thoracotomy is one such method that has been proposed; though, this requires resection of costal cartilage, which may lead to chest wall instability and increased pain for the patient (8). Reimplantation of the costal cartilage and standard right anterior thoracotomy using custom-fashioned rib-retractors has also been described (9,10). However, these methods have the disadvantages of limited exposure, frequent need for femoral artery cannulation and the attendant risk of life-threatening complications (11). Furthermore, the cosmetic advantage of an about 10 cm, right parasternal, asymmetrical scar is unclear (12).

Partial sternotomy approaches have been adopted most frequently. When used for aortic valve surgery these approaches all share a limited (10-12 cm) median skin incision, positioned in the upper, middle, or lower portion of the sternum. Aside from the technique entailing an upper skin incision starting at the suprasternal notch, which is of questionable cosmetic advantage, these other incisions are certainly preferable to the 18-20 cm incisions used in standard median sternotomy (13).

Partial sternotomy approaches to the aortic valve vary, depending on the way the sternum is divided. However, all share the same disadvantages in comparison with the median sternotomy: greater potential for sternal stump dehiscence, overriding, and fracture. These major complications have the potential to undermine the expected advantages of less invasive approaches. Another shared aspect of partial sternotomies is that, although conversion to a complete sternotomy may be relatively simple, it will result in complex sternal fractures that are difficult to stabilize.

The method proposed herein was originally tested for repair of simple septal defects (atrial, ventricular, and atrio-ventricular) in children and adults (5,14). The encouraging results prompted us to extend its use to elective aortic valve procedures and/or root aortic surgery. Among the advantages of a limited (mean 8 cm) skin incision with a complete median sternotomy are the cosmetic result (comparable to that of a partial sternotomy), the ease of execution with no need for custom-designed surgical instruments, and the exceptional versatility of the incision (mitral valve and coronary operations can also be performed with use of this technique).

Conversion to a “standard” approach is as simple as a skin incision, and chest stability after closure is comparable to that after a median sternotomy. Due to the limited dissection of the mediastinum and minimal spreading by the chest retractor, one can speculate that postoperative pain may be reduced.

In conclusion, a minimal-access full length median sternotomy combines the advantages of a cosmetically superior result with the safety and efficacy of median sternotomy and is particularly suited for elective, isolated AVR in patients who present with multiple extra-cardiac co-morbidities.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.von Segesser LK, Westaby S, Pomar J, et al. Less invasive aortic valve surgery: rationale and technique. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:781-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabata M, Umakanthan R, Cohn LH, et al. Early and late outcomes of 1000 minimally invasive aortic valve operations. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:537-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll N, Borger MA, Hain J, et al. Minimal access aortic valve replacement: effects on morbidity and resource utilization. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:S1318-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luciani GB, Mazzucco A. Aortic valve replacement via minimal-access complete sternotomy. Tex Heart Inst J 2000;27:286-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luciani GB, Piccin C, Mazzucco A. Minimal-access median sternotomy for repair of congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;116:357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aris A, Cámara ML, Montiel J, et al. Ministernotomy versus median sternotomy for aortic valve replacement: a prospective, randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1583-7; discussion 1587-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murtuza B, Pepper JR, Stanbridge RD, et al. Minimal access aortic valve replacement: is it worth it? Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1121-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazzara RR, Kidwell FE. Right parasternal incision: a uniform minimally invasive approach for valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:271-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minale C, Reifschneider HJ, Schmitz E, et al. Single access for minimally invasive aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:120-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benetti FJ, Mariani MA, Rizzardi JL, et al. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;113:806-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell MB, Brown JM, London MJ. Cardiac entrapment during minimally invasive aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:1171-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosgrove DM, 3rd, Sabik JF. Minimally invasive approach for aortic valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:596-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam RK, Almeida AA. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement via partial sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:275-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doty DB, DiRusso GB, Doty JR. Full-spectrum cardiac surgery through a minimal incision: mini-sternotomy (lower half) technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]