Summary

The bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS) couples phosphoryl transfer, via a series of bimolecular protein-protein interactions, to sugar transport across the membrane. The multitude of complexes in the PTS provides a paradigm for studying protein interactions, and for understanding how the same binding surface can specifically recognize a diverse array of targets. Fifteen years of work aimed at solving the solution structures of all soluble protein-protein complexes of the PTS has served as a test bed for developing NMR and integrated hybrid approaches to study larger complexes in solution and to probe transient, spectroscopically “invisible” states, including encounter complexes. We review these approaches, highlighting the problems that can be tackled with these methods, and summarize the current findings on protein interactions.

Keywords: signal transduction, protein-protein recognition, bacterial PTS, NMR spectroscopy, hybrid methods in structure determination, residual dipolar couplings, solution X-ray scattering, sparsely-populated states, encounter complexes

PTS as a paradigm for understanding complex protein interactions

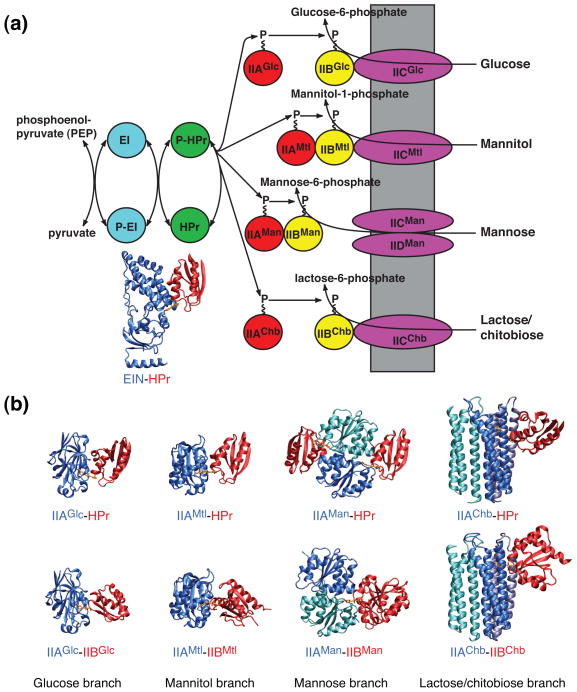

The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotrasferase system (PTS) is the key signal transduction pathway involved in the regulation of central carbon metabolism in bacteria [1–7]. The PTS comprises a sequential cascade of bimolecular protein-protein complexes whereby a phosphoryl group originating on phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) is transferred onto incoming sugars, thereby coupling phosphoryl transfer to active sugar transport across the membrane. The first two steps of the PTS are common to all sugars: Enzyme I (EI) is autophosphorylated by phosphoenolpyruvate and subsequently transfers the phosphoryl group to the histidine phosphocarrier protein HPr. HPr donates the phosphoryl group to the A component of the sugar specific Enzymes II. There are four classes of Enzymes II: glucose (the first branch of the PTS to have been discovered in 1964 [1]), mannitol, mannose, and lactose/chitobiose (Fig. 1A). The organization of the sugar-specific Enzymes II is similar: there are two cytoplasmic domains, IIA and IIB, and a transmembrane domain IIC, which may be supplemented by a fourth transmembrane domain IID. These domains may occur either as isolated proteins or be covalently joined by long linkers in a single contiguous protein (Fig. 1A). IIA accepts the phosphoryl group from HPr and donates it to IIB; finally the transmembrane domain IIC catalyzes the coupled translocation and phosphoryl transfer from IIB to the incoming sugar. Despite the similar organization of Enzymes II, the IIA domains from the four sugar classes bear no similarity to one another in terms of sequence, secondary, tertiary or quaternary structure [8–14]. The IIB domains from the mannitol [15, 16] and chitobiose [17, 18] branches are similar in terms of secondary and tertiary structure but have no significant sequence similarity outside of the active site loop. The active site loop of the IIB domain of the glucose branch [19] bears some similarities to that of the IIB domains from the mannitol and chitobiose branches, but displays no overall similarity in sequence, secondary or tertiary structure. Lastly the IIB domain of the mannose pathway [20–22] bears no similarity at all to that of the other three branches.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the PTS signal transduction pathway. (a) The first two steps are common to all branches of the pathway. Thereafter the pathway splits into four sugar-specific classes: glucose, mannitol, mannose and lactose/chitobiose. (b) Ribbon diagrams of the structures of the nine cytoplasmic complexes of the E. coli PTS. EIN-HPr [42] (shown in panel A); IIAGlc-HPr [47]; IIAMtl-HPr [45]; IIAMan-HPr[48]; IIAChb-HPr [49]; IIAGlc-IIBGlc [19]; IIAMtl-IIBMtl [50]; IIAMan-IIBMan [20]; IIAChb-IIBChb [51].

In addition to their function within the PTS cascade, components of the PTS are also involved in the regulation of many other proteins, including glycogen phosphorylase, adenylate kinase, glycerol kinase, various non-PTS permeases, and the global repressor Mlc. [3, 7] [23] [24] [25] [26, 27], In addition, under conditions of nitrogen limitation, competitive inhibition of EI by α-ketoglutarate [28], the carbon substrate for ammonia assimilation, blocks sugar transfer across the cell membrane, thereby providing a direct biochemical link between central nitrogen and carbon metabolism in bacteria [29].

Many reviews have been written on the biology of the PTS and on the structures of individual components of the PTS [2–7]. While crystal structures [8–13, 17, 21, 22, 30–35] have been solved for many of the cytoplasmic isolated proteins or domains of the PTS (the remainder being solved by NMR [14–16, 18–20, 36–41]), crystallization of PTS complexes has proved refractory. This is largely due to the fact that the complexes are transient and rather weak with equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) ranging from micro- to millimolar. Fortunately, this is not an impediment to the structure determination of such complexes in solution by NMR.

The multiplicity of protein-protein interactions in the PTS provides a paradigm for studying the factors governing specific recognition of multiple diverse targets. The current review focuses specifically on the NMR work in our laboratory, initiated in 1997 with the structure determination of the N-terminal domain of Enzyme I [39], aimed at understanding the structural basis of specific protein-protein recognition within the PTS, the fundamental biophysical mechanisms underlying protein-protein interactions, and the nature of large scale conformational rearrangements in multidomain proteins. In terms of structural biology and biophysics, these studies of protein-protein complexes of the PTS have provided a test bed for developing hybrid methods for solving the structures of large complexes and proteins in solution combining NMR and, in some instances, solution X-ray scattering, with crystal or NMR structures of individual domains, and for developing NMR methods for detecting and characterizing sparsely-populated, transient encounter complexes formed by random collisions between partner proteins that precede the formation of the specific complex.

Solving the 3D solution structures of PTS complexes

The first structure of a PTS protein-protein complex to be determined was that between the N-terminal domain of EI (EIN) and HPr [42] for which the traditional approach involving a complete NMR structure determination of the entire complex was employed (see Box 1). It was rapidly realized, however, that this very time consuming approach could be both speeded up and rendered more accurate by making use of the available crystal or NMR structures of the free proteins [43]. This assumes that the backbone conformation of the proteins undergoes minimal changes upon complex formation which can be ascertained both from the measurement of residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) as well as the observation of small backbone chemical shift changes upon complexation. The remainder of the PTS complexes were therefore solved by a procedure known as conjoined rigid body/torsion angle simulated annealing (see Box 2) in which the proteins are treated as rigid bodies that are free to translate and rotate relative to one another, and interfacial side chains are given torsional degrees of freedom [43, 44]. The driving force for these calculations resides in intermolecular nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE)-derived interproton distance restraints combined, where possible, with RDCs to provide orientational restraints and heteronuclear scalar couplings to derive torsion angle restraints for the interfacial side chains. This approach does not require that the complete backbone be treated as a rigid body: if there is evidence that a region(s) of the backbone undergoes a conformational change upon complexation, then it is a simple matter to give that region(s) torsional degrees of freedom whose conformational space is dictated by experimental NMR restraints (NOEs and RDCs measured on the complex) [45].

Box 1. Brief overview of NMR structure determination.

Traditionally, the geometric information used to solve 3D NMR structures of macromolecules relies principally on short (< 6Å) interproton distances derived from nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) measurements [92, 93]. Because many protons that are close in space are far apart in sequence, short interproton distance restraints are conformationally restrictive and sufficient, in their own right, to determine a 3D structure. Loose distance restraints, typically ranging from 1.8–2.7 Å, 1.8–3.5 Å, 1.8–5 Å and 1.8–6 Å, corresponding to strong, medium, weak and very weak NOEs, are adequate. Indeed, attempts to make use of more precise interproton distance restraints can often lead to a reduction in accuracy owing to a phenomenon known as spin diffusion whereby an NOE from say proton i to proton j is subsequently transferred to other protons in close proximity to proton j but far (> 5 Å) from proton i. Supplementary structural restraints on backbone torsion angles can be obtained from three-bond scalar couplings [94] and backbone chemical shifts [95]. But NOE and torsion angle restraints are short range in nature as they require close spatial proximity of the relevant atoms, and are therefore not good at specifying long-range order.

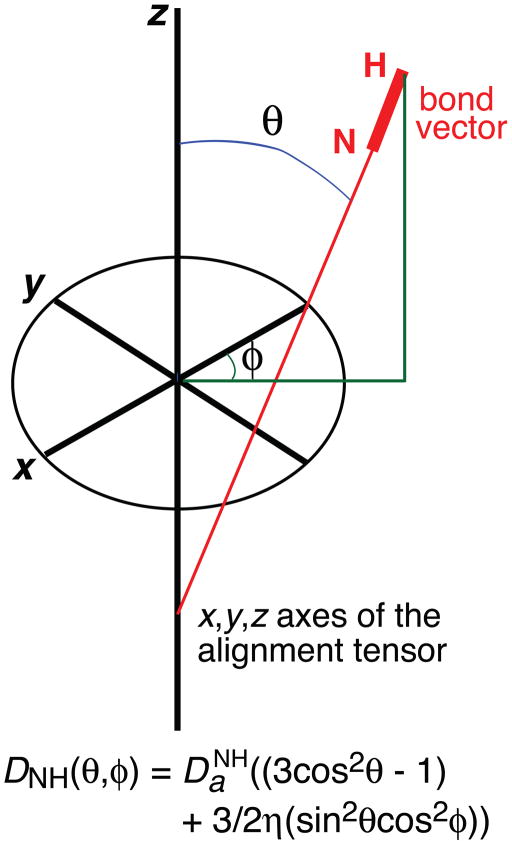

Long-range information can be obtained from residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) measured in a dilute liquid crystalline medium [96, 97] such as bicelles [98] or phage pf1 [99]. These media induce a small degree (~10−3) of alignment with respect to the magnetic field such that linewidths remain narrow but internuclear dipolar couplings are no longer averaged to zero by Brownian rotational diffusion. The value of an RDC (D) for an interatomic vector (such as a backbone N-H bond) is given by a simple geometric relationship that is dependent on the magnitude of the principal component of the alignment tensor Da, the rhombicity of the tensor η, and two angles θ and φ describing the orientation of the vector relative to the x, y, z axes of the alignment tensor (see Box 1 figure). RDCs are especially powerful for determining the relative orientation of two proteins within a complex as the two components share the same alignment tensor, and if the proteins can be treated as rigid bodies, only a small number of RDCs are required [43]. As a result it is possible to obtain an accurate structure of a protein-protein complex on the basis of only a few intermolecular NOEs to provide translational information, supplemented by RDCs for orientation.

Box 1 figure.

Box 2. Simulating annealing.

Simulating annealing is a heuristic global optimization method that is highly effective in circumventing local minima on the path to the global minimum of the target function being minimized. The underlying basis involves heating the system followed by slow cooling which has the effect of slowly decreasing the probability of accepting worse solutions, thereby permitting an extensive search for the optimal solution (i.e. the global minimum). There are several implementations of simulated annealing, including Monte Carlo methods and molecular dynamics. In the case of the complexes of the PTS, molecular dynamics-based simulated annealing was employed [44]. Several modalities can be used in combination permitting parts of the system to be treated as rigid bodies while giving conformational degrees of freedom (either in torsion angle space or in Cartesian coordinate space) to other parts (such as interfacial side chains or linkers connecting two proteins). The target function that is minimized comprises terms for the experimental restraints (e.g. NOE-derived interproton distances, torsion angles, chemical shifts, paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data, X-ray scattering data, etc…), non-bonded contact terms to prevent atomic overlap, conformational database potentials to ensure that torsion angles lie in physically realistic regions of conformational space, and geometric restraints. In most instances only a single set of coordinates is refined against the experimental data. In some instances, however, especially when dealing with encounter complexes, an ensemble of structures is required to represent data. This necessitates the use of ensemble refinement where multiple copies of the coordinates are refined simultaneously.

Whether one chooses to do a full NMR structure determination or to make use of known structures of the free protein, it is essential to distinguish unambiguously intermolecular NOEs from intramolecular NOEs within the individual proteins. This is readily accomplished by making use of appropriate isotopic labeling of the individual proteins [46]. For example, by 13C labeling one protein and having the other protein at natural isotopic abundance one can make use of three-dimensional 12C-filtered/13C-separated NOE experiments to specifically observe NOEs from protons attached to 13C in the first protein to protons attached to 12C in the second. Many other labeling combinations can also be employed, including 13C-labeling one protein and 15N-labeling the second to observe NOEs between protons attached to 13C in the first protein and protons attached to 15N in the second. As the complexity and size of the complex increases it is also very useful to make use of residue specific isotope labeling, especially of methyl bearing side chains.

In solving the structures of the IIA-HPr [45, 47–49] and IIA-IIB [19, 20, 50, 51] complexes, existing crystal structures of the individual domains were used where available and their accuracy verified by agreement of RDCs with the coordinates; structures involving IIBGlc, IIBMtl, IIBMan and IIAChb made use of high accuracy NMR structures solved on the basis of extensive NOE and RDC data; finally, in the case of IIBChb, the X-ray coordinates were employed while giving the active site loop torsional degrees of freedom. Interestingly, the crystal structure of IIBGlc in complex with the global repressor Mlc [52] was solved 5 years after the NMR structure of IIBGlc complexed to IIAGlc [19], and the backbone atomic rms difference between the IIBGlc structures was only 0.37 Å, making IIBGlc one of the most accurate de novo NMR structure determined to date prior to the availability of an X-ray structure.

Solution structures of the PTS complexes – specific recognition of structurally diver partners

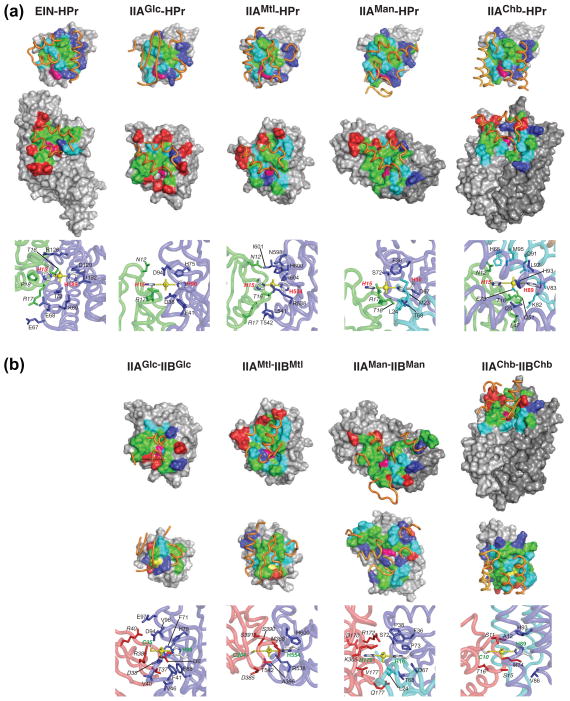

The structures of all nine soluble complexes of the PTS are presented in Fig. 3. HPr interacts with 5 different proteins (EIN, IIAGlc, IIAMtl, IIAMan and IIAChb) which display no similarities with regard to primary, secondary, tertiary or quaternary structure. The only apparent commonality is that the active site residue is a histidine, and in each case a pentacoordinate phosphoryl transition state can be modeled without necessitating any significant change in backbone coordinates. For the four IIA-IIB complexes, three involve phosphoryl transfer from a histidine on IIA to a cysteine on IIB. In the IIAMan-IIBMan complex phosphoryl transfer occurs from a histidine to a histidine. As in the case of the complexes with HPr, the phosphoryl transition state can be modeled with no significant changes in backbone coordinates. Thus, phosphoryl transfer for all cytoplasmic complexes of the PTS can proceed with maximum energetic efficiency without incurring an energetic penalty from any significant conformational changes required for either partner protein.

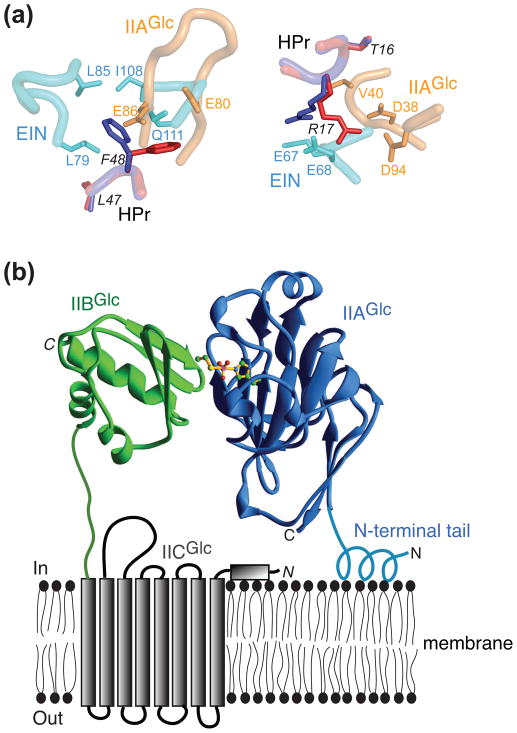

Fig. 3.

Role of conformational side chain plasticity and membrane anchoring tails in protein complexes of the PTS. (a) Conformational side chain plasticity illustrated by complexes of HPr with EIN and IIAGlc. EIN is shown in cyan, IIAGlc in orange, HPr in the EIN-HPr complex in blue, and HPr in the IIAGlc-HPr complex in red. Residues of HPr are labeled in italics. Alternate conformations for Phe48 and Arg17 of HPr are illustrated in the left and right panels, respectively. Adapted from [47]. (b) Role of the N-terminal tail of IIAGlc in facilitating phosphotransfer to IIBCGlc. IIAGlc is shown in blue and residues 2–10 adopt a helical conformation upon interaction with the lipid bilayer of the bacterial cell membrane, thereby stabilizing the IIAGlc-IIBCGlc complex by partially anchoring IIAGlc to the lipid membrane. IIBGlc is shown in green, and a cartoon of the transmembrane IICGlc domain which includes eight transmembrane helices is shown in grey. Adapted from [19].

Despite the apparent lack of similarity in the complexes at the level of the ribbon diagrams shown in Fig. 1B, the interaction surfaces are actually similar despite the different underlying secondary and tertiary structural elements. This is apparent from the molecular surface representations of the interfaces shown in Fig. 2. All the protein-protein interfaces are characterized by large buried accessible surface areas ranging from 1200–1800 Å2 with approximately equal contributions from both partners. The interaction surfaces for HPr and Enzymes IIB are convex, while those of EIN and Enzymes IIA are concave, providing shape complementarity. In general each interaction surface comprises a predominantly hydrophobic central region interspersed with scattered polar residues, and asymmetrically distributed charged residues at judicious locations along the outer edges of the interaction surface. The active site residue is offset from the center of the binding site. Surface complementarity is largely provided by the hydrophobic residues while electrostatic interactions serve to modulate affinity and direct the exact relative orientation of the partner proteins within a given complex. Sequences comparisons over several species indicates that while the absolute identity of the hydrophobic residues at the interface may vary, the network of intermolecular hydrophobic interactions is preserved and substitutions are in general compensatory such that the packing density at the interface across different species remains largely unperturbed [19, 42].

Fig. 2.

Summary of interaction surfaces for the cytoplasmic complexes of the PTS. Complexes of (a) EIN and the four classes of enzymes IIA with HPr and of (b) the four classes of Enzymes IIA with their respective Enzyme IIB counterparts. (a) Top row, interaction surfaces on HPr; middle row, interaction surfaces on EIN and Enzymes IIA; bottom row, close up of the phoshoryl transition states. (b) Top row, interaction surfaces on Enzymes IIA; middle row, interaction surfaces on Enzymes IIB; bottom row, close up of the phoshoryl transition states. For both panels (a) and (b) residues on the interaction surfaces (top and middle rows) are color-coded as hydrophobic (green), hydrophilic (cyan), positively charged (blue), negatively charged (red), active site histidine (purple) and active site cysteine (yellow). Also shown in the top and middle rows are the relevant portions of the backbone of the interacting partner displayed as gold tubes. In the bottom row of panel (a), HPr is displayed in green, EIN and Enzymes IIA in blue, and the pentacoordinate phosphoryl group in yellow; residues labels for HPr are in italic. In the bottom row of panel (b), Enzymes IIB are displayed in red, Enzymes IIA in blue, and the pentacoordinate phosphoryl group in yellow; residues labels for Enzymes IIB are in italic. EIN-HPr [42]; IIAGlc-HPr [47]; IIAMtl-HPr [45]; IIAMan-HPr[48]; IIAChb-HPr [49]; IIAGlc-IIBGlc [19]; IIAMtl-IIBMtl [50]; IIAMan-IIBMan [20]; IIAChb-IIBChb [51].

HPr uses essentially the same convex surface to interact with all its partners, and all charged residues on the interaction surface of HPr are positive (Fig 2A, top row). A key feature of the interactions of HPr with its partner proteins is redundancy of charged residues such that the disposition of the complementary negatively charged residues on the partner proteins need not be identical. Thus, not all charged residues present at the protein-protein interface are involved in salt bridge interactions. In the same vein, each Enzyme IIA uses largely the same binding surface to interact with HPr and its IIB partner (cf. compare the middle row of Fig. 2A with the upper row of Fig. 2B).

One might therefore ask why it is that the Enzymes IIB cannot bypass the corresponding Enzymes IIA and interact directly with EIN? The is because the binding surfaces on all the Enzymes IIB differ from that of HPr in one very significant way: while the majority of charged residues in the IIB binding site are positive, there are one or two negatively charged residues (Fig. 2B, middle row) that complement positively charged residues on the corresponding IIA (Fig. 2B, upper row), but would be repulsed by negatively charged residues on the surface of EIN (Fig. 2A, upper row).

Another key feature of the binding surfaces that permits specific recognition of a wide variety of partners is side chain conformational plasticity, illustrated in Fig. 3A for several side chain interactions between HPr and EIN or IIAGlc [47]. For example, the side chain of Phe48 undergoes a conformational switch from one rotamer in the EIN-HPr complex to another in the IIAGlc-HPr complexes, thereby permitting Phe48 to interact with hydrophobic components on the partner proteins, specifically the methyl groups of Leu79, Leu85 and Ile108 for EIN, and the backbone residues of a β-sheet for IIAGlc (Fig. 3A, left panel). Likewise Arg17 of HPr interacts in one side conformation with Glu67 and Glu68 of EIN and in another conformation with Asp38 and Asp94 of IIAGlc (Fig. 3A, right panel)

The phosphoryl transition state intermediate

Phosphoryl transfer in the PTS complex occurs via in-line phosphoryl transfer in which the donor atom, the phosphorus and the acceptor atom lie along a straight line [53]. Isotope labeling experiments have shown that odd and even numbers of phosphoryl transfer steps result in inversion and retention, respectively, of the configuration of the phosphorus [54, 55], indicating that the transition state involves a pentacoordinate phosphoryl transition state in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry, with the donor and acceptor atoms in apical positions, and the oxygen atoms lying in the equatorial plane. The phosphoryl transition states can be modeled by introducing a phosphoryl group subject to restraints related to trigonal bipyramidal geometry at the phosphorus group. Phosphorylation occurs at the His(Nε2) atom for EIN and the four Enzymes IIA, at the His(Nδ1) atom for HPr and IIBMan, and at the Sγ atom of cysteine for the remaining Enzymes IIB. The phosphoryl transition state can be formed without altering the position of the two partner proteins and with minimal changes in backbone coordinates immediately adjacent to the active site histidine or cysteine residues (Figs 2A and B, bottom row). The distances between the acceptor and donor atoms in the transition state can potentially range from the sum of the donor atom-phosphorus atom and phosphorus atom-acceptor atom bond lengths to the sum of the van der Waals radii of the donor, phosphorus (x 2) and acceptor atoms, corresponding to fully associative and fully dissociative mechanisms, respectively. The N-P and S-P distances in the modeled transition states are consistent with substantial dissociative character, as predicted from a comparison of linear free energy relationships for non-enzymatic and enzymatic phosphoryl transfer reactions [56]. Although the resolution of the structures of the complexes is limited, a fully associative mechanism would require substantial distortions and strain in the backbone adjacent to the donor and acceptor residues.

The phoshoryl transition states are shown in the lower rows of Figs. 2A and B. The phosphoryl group and the active site histidines and/or cysteines lie on a bed of hydrophobic residues, and the phosphoryl group itself is stabilized by hydrogen bonding interactions involving polar (Thr, Ser, His) or charged (Arg) residues. The number of hydrogen bonds to the phosphoryl group from each partner (both in the transition state and in models of the individual phosphorylated proteins), at least in the case of the glucose pathway where measurements of the various equilibria are available, correlates with the directionality of phosphoryl transfer. Thus, the phosphoryl transfer from EIN to HPr and from IIAGlc to IIBGlc are favored by factors of ~10 and ~3, respectively, over the reverse transfers, while the phosphoryl transfers from HPr to IIAGlc and from IIAGlc to HPr are equally favorable [57], consistent with the larger number of hydrogen bonds stabilizing the phosphoryl group originating from HPr than EIN and from IIBGlc than IIAGlc, while the same number of hydrogen bonds stabilize the phosphoryl group in HPr and IIAGlc.

Impact of linkers connecting PTS domains on the efficiency of phosphoryl transfer

Many of the domains of Enzymes II are connected by long flexible linkers. For example, the A, B and transmembrane C domains of Enzyme IIABCMtl and the A and B domains of Enzyme IIABMan are expressed as single proteins, as are the IIBGlc and transmembrane IICGlc domains of IIBCGlc [3]. In addition, many of the PTS complexes have KD’s in the high micromolar to millimolar range [20, 45, 48–51]. The KD for the interaction of the isolated IIAMtl and IIBMtl domains is 3–4 mM [50], while that of the isolated IIAMan and IIBMan domains is ~0.5 mM [20].

Tethering two domains increases their effective local concentration, thereby increasing the probability of complex formation. The A and B domains of IIMtl are connected by a 21 residue flexible linker, from which one can calculate, using well-established polymer chain theory, that the effective local concentration of the A and B domains is ~ 4 mM [50]. This value is consistent with 15N relaxation dispersion mesurements on IIABMtl that yield a population of ~50% for the associated state with a unimolecular association rate constant of ~20,000 s−1 for the interaction of the tethered A and B domains [58]. The latter corresponds to an apparent bimolecular association rate constant of 5x106 M−1s−1 [58] which is within the range typically observed for specific protein-protein interactions (0.5–5 x 106 M−1s−1) and in excellent agreement with the predicted value of 2 x 106 M−1s−1 for a purely diffusive process obtained from Brownian dynamics simulations [59]. Thus the linker serves to optimally tune the system to achieve reasonable high occupancy coupled with rapid association and dissociation (~20,000 s−1 in both directions) to efficiently carry out three sequential phosphoryl transfer steps from HPr to IIAMtl, from IIAMtl to IIBMtl and finally from IIBMtl onto the incoming sugar bound to the cytosolic side of IICMtl. The phosphoryl transfer rate between the A and B domains of IIAMtl determined from NMR lineshape analysis is ~500 s−1 in both directions [58]. Since this value is ~40-fold lower than the rate constants for intramolecular domain-domain association and dissociation, one can calculate that ~80 association/dissociation events take place for every phosphoryl transfer reaction. The rate limiting step for phosphoryl transfer between the A and B domains of IIABMtl is therefore governed by the chemistry of the phosphoryl transfer reaction itself rather than the rate of association to form the specific complex or the rate of dissociation to permit the next phosphoryl transfer reaction in the pathway to take place.

The glucose Enzymes II exhibit a variant of this phenomenon. While the B and C domains are tethered by a ~75 residue linker, the A domain is expressed as a separate protein. The first 18 residues of IIAGlc are disordered in solution and while the presence or absence of the N-terminal tail has no effect on phosphoryl transfer between HPr and IIAGlc, the presence of the N-terminal tail is critical for efficient phosphoryl transfer to IIBGlc in vivo [60, 61] It turns out that residues 2–10 of the N-terminal tail of IIAGlc associate with E. coli membranes to form an amphiphatic helix [62], thereby bringing IIAGlc in close proximity to IIBGlc and stabilizing the IIAGlc-IIBGlc interaction by effectively increasing the local concentration of IIAGlc and IIBCGlc (Fig. 3B).

The solution structure of intact Enzyme I and its complex with HPr – approaches to solving structures of larger (>100 kDa) complexes in solution

The N-terminal domain (EIN) of EI can transfer a phosphoryl group to and accept a phosphoryl group from HPr but cannot be autophosphorylated by phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) [63–66]. Autophosphorylation of EI requires the presence of the C-terminal dimerization domain EIC. Intact EI is a 128 kDa dimer and therefore very large by NMR standards. The probability of successfully solving a structure of this size using conventional NMR methodology is very small and even if it could be done, the coordinate accuracy would be low. To efficiently and accurately solve the solution structure of such a system therefore requires the development of hybrid methodology that makes use of prior available structural information combined with limited solution RDC and small (SAXS) and wide (WAXS) angle X-ray scattering [40].

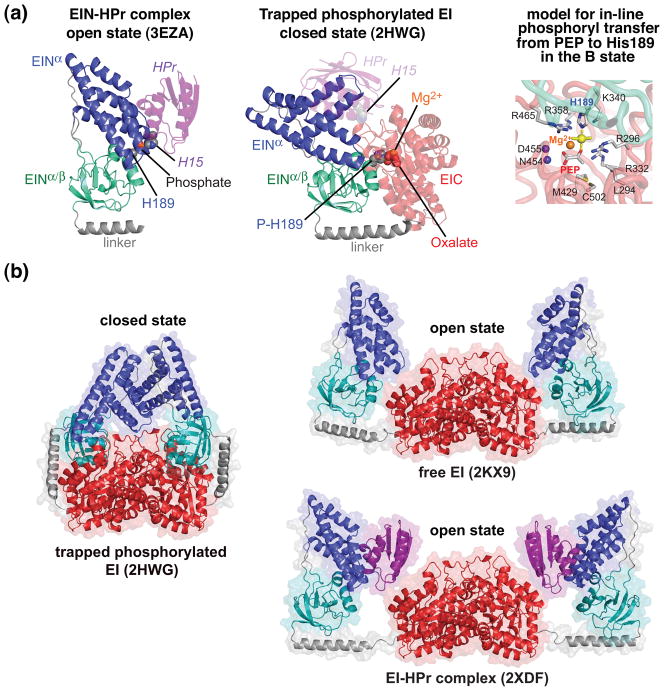

The crystal structure of a trapped phosphorylated intermediate of intact E. coli (Fig. 4A, middle panel, and Fig. 4B, left panel) was solved by crystallizing EI from a solution containing PEP and Mg2+ and then quenching the autophosphorylation reaction using the inhibitor oxalate [33]. A comparison of the structure of the EIN domain in the EI phosphorylated intermediate with that of the isolated EIN domain, both free (X-ray [30] and NMR [39]) and complexed to HPr [42], reveals major conformational changes in the disposition of the two subdomains, α and α/β, of EIN (Fig. 4A). The EINα subdomain provides the interaction surface for HPr, while the EINα/β subdomain contains the active site histidine, His189 [42]. The position of the active site histidines of HPr (His15) and EIN (His189) in the EIN-HPr complex allows for in-line phosphoryl transfer between EIN and HPr without requiring any substantial conformational changes (Fig. 2A and Fig. 4A, left panel) [42]. In the phosphorylated EI intermediate [33], the EINα subdomain undergoes a reorientation of ~70° relative to the EINα/β subdomain such that the Cα-Cα distance between the active site histidines of HPr and EIN would be increased from ~12 Å in the EIN-HPr complex to ~30Å (Fig. 4A, middle panel), a distance far too large to permit phosphoryl transfer from EIN to HPr. However, the active site His189 in the EINα/β subdomain of the phosphorylated EI intermediate is optimally positioned for phosphoryl transfer from PEP bound to the EIC domain to His189 (Fig. 4A, left panel) [33]. If the orientation of the EINα/β subdomain relative to the EIC dimer in in the crystal structure of the phosphorylated intermediate were preserved, the EINα subdomain would interpenetrate the EIC domain in the configuration found in the isolated EIN domain (see Fig. 4A). Thus the transition from free EI to phosphorylated EI must be accompanied by two major rigid body conformational rearrangements involving reorientation of EINα/β relative to EIC and of EINα relative to EINα/β.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of open and closed states of EI. (a) The open state is found in the isolated EIN domain (left panel) and in intact EI both free and in complex with HPr [30, 39–42]; the closed state (middle panel) is found in the crystal structure of the trapped phosphorylated intermediate of EI [33]. The EINα/β subdomain (cyan) is shown in the same orientation in both panels. Only a single subunit of phosphorylated EI is shown. The color coding is as follows: EINα, blue; EINα/β, cyan; EIC, red; linker connecting EINα/β to EIC, brown; HPr, purple. HPr bound to the EINα subdomain of phosphorylated EI (closed state) in the same orientation as in the EIN-HPr complex (open state) is shown in the middle panel as a transparent purple ribbon to illustrate that the HPr binding site is available in the closed state and there are no clashes between HPr and EIC in this conformation, but that the distance between His15 of HPr and His189 of EINα is much too large (~30 Å) to allow phosphoryl transfer from EIN to HPr to take place in the closed state. The right panel shows a model of in-line phosphoryl transfer from PEP to His189 in the closed state. (b) Comparison of the crystal structure of the trapped phosphorylated intermediate of the EI dimer (closed state) with the solution structures of the free EI dimer and the dimeric EI-HPr complex (open state) determined from combined use of NMR residual dipolar couplings and solution X-ray scattering (SAXS/WAXS). The color coding is the same as in (a).

RDCs measured on the EIN domain of intact EI (both free and complexed to HPr) are in excellent agreement with the orientation of the EINα and EINα/β subdomains in the isolated EIN domain, but are inconsistent with that in the crystal structure of the EI phosphorylated intermediate. Thus one can conclude unambiguously that the relative orientation of the EINα and EINα/β subdomains in free and HPr-bound full length EI remains unchanged relative to that in the isolated EIN domain [40].

The hybrid approach used to solve the structure of free EI and the EI-HPr complex made combined use of RDCs and SAXS/WAXS. The RDCs restrain the relative orientations of the EINα and EINα/β subdomains within each subunit and of the two symmetry-related EIN domains in the dimer. Since the structure of the EIC domain dimer is the same in several EI and isolated EIC structures [33–35, 67, 68], the orientation of the symmetry-related EIN domains relative to the EIC dimer can be determined from RDCs located only in the EIN domain, since one of the principal axes of the alignment tensor must coincide with the C2 symmetry axis of the dimer (since the RDCs for the two identical subunits are the same). RDCs alone are not sufficient to determine a unique structure owing to the existence of several equivalent solutions arising from the intrinsic equivalence of 180° rotations about the axes of the RDC alignment tensor. However, when the RDCs are combined with stereochemical and covalent geometry restraints within the linker connecting the EIN and EIC domains together with shape and translational information contained within the SAXS/WAXS profiles, only a single solution emerges from RDC and SAXS-WAXS-driven simulated annealing calculations in which the domains are treated as rigid bodies and only the linker (residues 255–261) is allowed to vary in conformation [40, 41].

The RDCs and SAXS/WAXS profiles [40] do not agree with the crystal structures of phosphorylated E. coli EI (Fig. 4B, left panel) [33] or free S. aureus [35] and S. carnosus [34] EI. The χ2 for the fits to the SAXS/WAXS data (from scattering vector values of q = 0.014 to 0.44 Å−1) are 128, 56 and 30 for the three crystal structures, respectively. The same is true of small angle neutron scattering (SANS) with χ2 values of 62, 34 and 30, respectively. Moreover, the calculated Svdeberg sedimentation coefficient for phosphorylated EI (S = 6.74) and free S. aureus EI (S = 6.45) are significantly larger than the experimental value (S = 5.68) determined by sedimentation velocity, indicating that the structures are too compact, while that for S. carnosus EI (5.55) is too small [40], reflecting an overly expanded structure. In addition, the structure of the EIN domain in the S. carnosus crystal structure is partially disordered.

The solution structures of E. coli free EI and EI complexed to HPr determined by conjoined rigid body/torsion angle/Cartesian simulated annealing driven by RDCs and SAXS/WAXS are shown in Fig. 4B [40]. Both structures are independently validated by agreement to both WAXS at high q (0.44 to 0.8 Å−1) and SANS. The latter provides an independent validation tool for the EI-HPR complex as contrast-matching was used to render the HPr component invisible (by using a complex of deuterated EI and protonated HPr in 40.4% D2O).

The relative orientation of EIN relative to EIC in free EI and the EI-HPr complex are not identical (Fig. 4B, right panel). For free EI, the EIN domain makes quite extensive contacts (~300 Å2 of buried accessible surface area) with the EIC domain with a number of complementary charge-charge interactions. In this configuration, HPr bound to the EINα subdomain would partially overlap with the EIC domain. Binding of HPr to the EINα subdomain is accompanied by additional movement of the EIN domain away from the EIC domain to make room for HPr, such that HPr is sandwiched between the EIN and EIC domains. There are a small number of contacts between HPr and EIC involving several complementary electrostatic interactions with a buried accessible surface area of ~100 Å2. The conformational transition of the EIN domain from the free EI configuration to that of the EI-HPr configuration is achieved by only minor changes in backbone torsion angles within the linker connecting the EINα/β subdomain to the EIC domain.

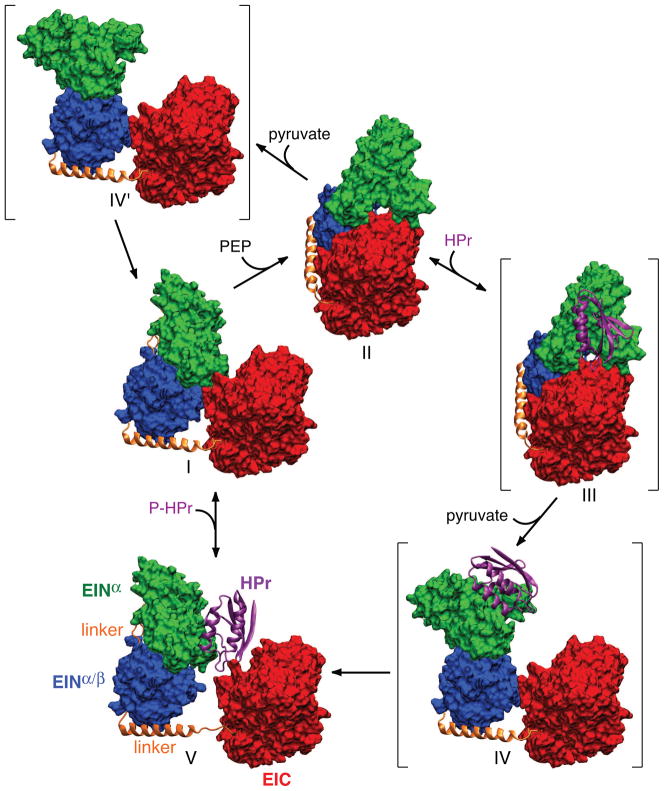

Fig. 5 depicts the postulated catalytic cycle for EI [40]. The change in configuration of the EIN domain from that of the phosphorylated EI intermediate to that of free EI and the EI-HPr complex must involve two sequential or concerted conformational transitions. First, a ~70° reorientation of EINα/β relative to EIC, accompanied by a ~34 Å rms displacement of the EINα/β subdomain. Second, a ~70° reorientation of EINα relative to EINα/β through backbone torsion angle changes within the two linkers joining the EINα to EINα/β subdomains. The latter cannot occur first since EINα would clash with EIC in the absence of any accompanying reorientation of EINα/β.

Fig. 5.

Catalytic cycle of EI. Only a single subunit is displayed for clarity with the molecular surfaces of the EINα and EINα/β subdomains of EIN in green and blue, respectively, the molecular surface of EIC domain in red, the linker connecting EINα/β to EIC in a gold ribbon, and HPr in a purple ribbon. Structures I and V correspond to free EI and the EI-HPr complex (open state) solved by NMR and SAXS/WAXS, structure II to the crystal structure of the trapped phosphorylated intermediate (closed state), and structures III, IV and IV′ (shown in brackets) to postulated intermediates. Structure III corresponds to the binding of HPr to the trapped phosphorylated intermediate; structures IV and IV′ correspond to structures in which the orientation of the EINα/β subdomain relative to EIC is the same as that in free EI (I) or the EI-HPr complex (V), while the orientation of the EINα subdomain relative to EINα/β is the same as that in the trapped phosphorylated intermediate (II). The EIC domain (red) is displayed in the same orientation for all structures. Adapted from [40].

Although the SAXS/WAXS, SANS and RDC data for EI and the EI-HPr complex can be satisfied by a single structure, it is likely that interdomain motions and sparsely-populated states are present. However, since the RDC and X-ray scattering data are sensitive to different types of motion, the former being dependent on orientation and the latter on molecular size and shape, one can be confident that the calculated structures are representative of the predominant average structure in solution.

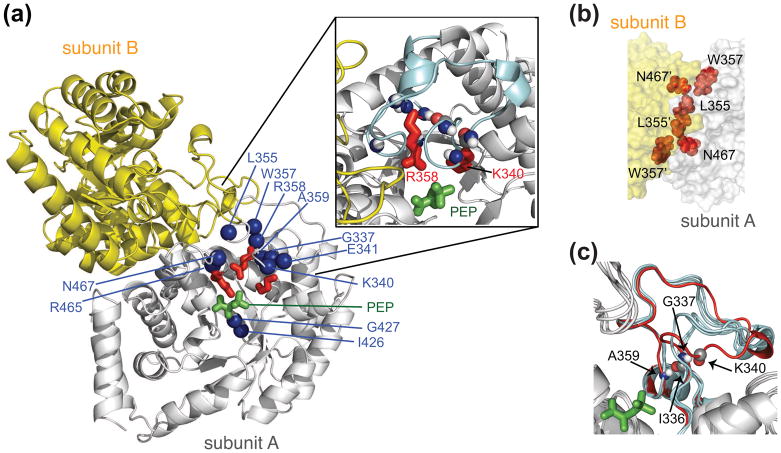

Interplay between conformational dynamics and dimerization of the EIC domain

Binding of PEP and Mg2+ to EI results in a ~30-fold decrease in the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kdimer) for the dimer [69, 70]. The decrease in Kdimer upon ligand binding is thought to play an important role in regulating the PTS as only intact dimeric EI can be autophosphorylated by PEP [70]. Binding of PEP to the dimeric isolated EIC domain results in quite large 1HN/15N chemical shift perturbations around the PEP binding site and in the adjacent β3α3 turn located at the dimer interface [71]. Examination of EIC in various crystal structures [33–35] [67, 68] suggests that the β3α3 turn exists in open and closed conformations, with the latter corresponding to the conformation in the phosphorylated EI intermediate (Fig. 6). 15N relaxation dispersion measurements reveal the existence of a dynamic equilibrium between major (97%) and minor (3%) species with an overall exchange rate of ~1550 s−1 [71]. The backbone 15N chemical shift differences between the major and minor species in free EIC determined from the relaxation dispersion data correspond nicely with the chemical shift differences observed upon addition of PEP [71]. Thus, it is likely that binding of PEP occurs via conformational selection of a low-population state corresponding to the closed state of the β3α3 turn.

Fig. 6.

Structure and dynamics of the isolated EIC dimer. (a) Structural model of the E. coli EIC-PEP complex derived from the crystal structures of the T. tengcongensis EIC-PEP complex [68] and the E. coli phosphorylated EI intermediate [33]. One subunit is in grey, the other in yellow. PEP is in green; the side chains of Lys340, Arg358 and Arg 465 in red; and backbone nitrogen atoms exhibiting significant relaxation dispersion, characteristic of motion on the submillisecond to millisecond time scale, in blue. The inset shows a close-up of the β3α3 turn. (b) Close-up view of the EIC dimer interface. (c) Superposition of the crystal structures of EIC [33–35] [67, 68], illustrating the conformational variability of the β3α3 turn, with the closed conformation of the β3α3 turn seen in the crystal structure of the trapped phosphorylated EI intermediate in red. (D) The overall exchange rate between major (97%) and minor (3%) species determined by 15N-NMR relaxation dispersion spectroscopy is ~1550 s−1. The 15N chemical shift differences between the major and minor species determined from relaxation dispersion on free EIC correspond closely to the differences in chemical shifts between free EIC and EIC complexed to PEP, strongly suggesting that the minor species represents the closed conformation of the β3α3 turn. Adapted from [71].

Encounter complexes in the PTS

Specific protein-protein recognition generally proceeds via a two-step process involving the initial formation of an ensemble of short-lived encounter complexes via diffusion-controlled intermolecular collisions, followed by translations and rotations of the two partner proteins down a two-dimensional funnel-like energy landscape resulting in the formation of a well-defined specific complex stabilized by a complementary set of electrostatic and van der Waals interactions [72, 73]. Encounter complexes are thought to play an important functional role in fine-tuning reaction fluxes inside the cell [74] by enhancing association on-rates through an increase in the interaction cross-section and a reduction in the conformational search space on the path to the specific complex [75–78]. Encounter complexes are generally extremely difficult to study experimentally as they are short-lived, highly transient and sparsely-populated, and therefore invisible to conventional structural and biophysical methods.

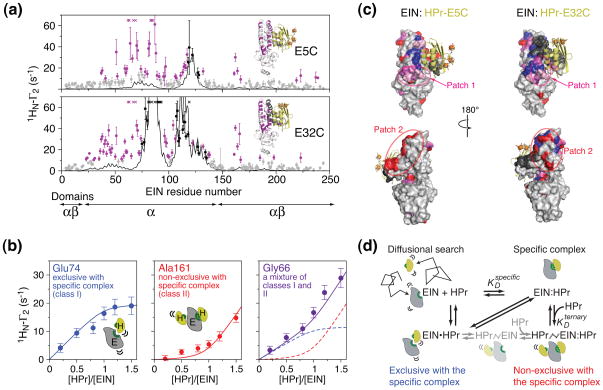

Transient, sparsely-populated states, however, can be studied by NMR using paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) (see Box 3). A comparison of the experimental PRE profiles for the EIN-HPr complex with those calculated from the structure of the specific EIN-HPr complex is shown in Fig. 7A [79]. The paramagnetic tag (EDTA-Mn2+) that gives rise to the PRE was covalently attached to three sites (E5C, E25C and E32C) on HPr (at natural isotopic abundance) using surface engineered cysteines, while EIN was uniformly labeled with 15N. This isotopic labeling scheme permits one to specifically detect intermolecular PRE effects originating from the paramagnetic label attached to HPr on the backbone amide resonances of EIN. It can be seen that while there are features of the experimental intermolecular PRE profiles (black circles) that match the calculated profiles for the specific complex, there are regions where the observed intermolecular PREs (purple circles) are much larger than the calculated values. Thus, there are regions on EIN that spend a small proportion of time much closer to the paramagnetic tags on HPr than in the specific complex. Similar observations were made for complexes of HPr with IIAMtl and IIAMan [80].

Box 3. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement and the detection of sparsely-populated states.

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) is an NMR technique that involves covalently attaching a paramagnetic tag (such as a nitroxide or EDTA-Mn2+) to an engineered surface exposed cysteine residue [80, 100, 101]. The PRE effect (measured by the difference in 1H transverse relaxation rates between samples with and without the paramagnetic tag) is proportional to the <r−6> separation between the paramagnetic tag and the protons of interest. (1H transverse relaxation rates reflect the linewidths of the 1H resonances in the NMR spectrum, the larger the 1H transverse relaxation rate, the broader the resonances). Since the magnetic moment of an unpaired electron is large, the PRE at short distances is correspondingly very large. For example, for a 20–30 kDa molecule, the transverse PRE rate (Γ2) for a 30 Å distance would be ~2 s−1, while that for an 8 Å distance would be ~6000s−1. In a system comprising two species, one populated at 99% with a distance of 30 Å, the other at 1% with a distance of 8 Å, that exchange fast on the PRE time scale (defined as an exchange rate larger than the difference in PRE rates for the two species), the PREs observed on the spectrum of the major species will be a population weighted average of the PRE rates for the major and minor species; in this particular example, the PRE rate measured on the spectrum of the major species would therefore be around 50–60 s−1. As a result, the imprint of the invisible minor species will be reflected in the PRE profiles measured on the spectrum of the major species, providing there are paramagnetic tag-proton distances that are shorter in the minor species than the major one.

Fig. 7.

Characterization of transient sparsely-populated encounter complexes for the interaction of EIN and HPr. (a) Comparison of experimental backbone amide intermolecular PREs (1HN-Γ2) (circles) observed on 15N-labeled EIN and arising from covalently attached paramagnetic tags (EDTA-Mn2+) located at two positions on HPr (E5C and E32C) with the PRE profiles calculated from the structure of the specific complex (black line). Black and purple circles indicate PREs attributable to the specific complex and to an ensemble of encounter complexes, respectively. (b) Intermolecular PREs as a function of added paramagnetically-labeled HPr(E5C) illustrating three types of titration behavior. (c) Mapping of intermolecular PREs attributable to the specific complex (black) and to the encounter complexes (class I, blue; class II, red; mixture of classes I and II, purple; and encounter complex PREs that are too large to measure accurately, pink). (d) Equilibrium binding model for the EIN/HPr association pathway. Adapted from [79]

The discrepancies between observed and calculated intermolecular PREs can be fully accounted for by the presence of a small population (~5–10%) of transient encounter complexes whose distribution can be calculated using PRE-driven rigid body ensemble simulated annealing [80] (see Box 2). The calculated distribution of HPr on the surface of EIN is largely correlated with surface electrostatics, which was confirmed experimentally by the observation that the intermolecular PREs arising from the encounter complexes are significantly more sensitive to ionic strength than those from the specific complex [81].

Further analysis of the intermolecular PRE intensities as a function of added paramagnetically-labeled HPr yield further insights into the nature of the encounter complexes [79]. The PREs attributable to the specific complex titrate as a simple one-site binding isotherm with a KD of ~ 7 μM, in agreement with the KD determined by isothermal titration calorimetry. The PREs arising from the encounter complexes, however, titrate as three classes (Fig. 7B). Class I PREs display the same titration behavior as the intermolecular PREs arising from the specific complex. Thus, these intermolecular PREs arise from encounter complexes that are exclusive with the specific complex (i.e. the binding sites must overlap such that the specific complex and the class I encounter complexes cannot occur together). Class II PREs follows the concentration of free HPr, and therefore arise from encounter complexes that are non-exclusive with the specific complex (i.e. class II encounter complexes co-exist with the specific complex). Finally, class III PREs exhibit a mixture of class I and II behavior. When the three classes of encounter complex PREs are mapped onto the surface of EIN, it is clear that class I PREs report on encounter complexes interactions near the active site of EIN that are occluded by the specific complex (Fig. 7C). The class II PREs report on ternary HPrnonspecific/EIN/HPr complexes that predominate when the active site is occupied by the specific complex (Fig. 7C). These finding can be summarized by the equilibrium binding model shown in Fig. 7D.

What is the possible role of the transient HPrnonspecific/EIN/HPr ternary complexes? It is possible that these ternary complexes may help EI compete for the cellular pool of HPr, even while phosphotransfer is occurring at the EIN active site, thereby facilitating higher rates of sugar uptake when substrate is transiently abundant [79]. In other words, the ternary complexes may be important for efficiently reloading the EIN active site with HPr when demand for sugar transport is high. Given the intracellular concentrations of EI and HPr (5 and 20–100 μM, respectively), one can estimate that the population of ternary complex ensembles in vivo is ~1%. This estimate may be revised higher if intracellular crowding and compartmentalization further favors the formation of transient ternary complexes.

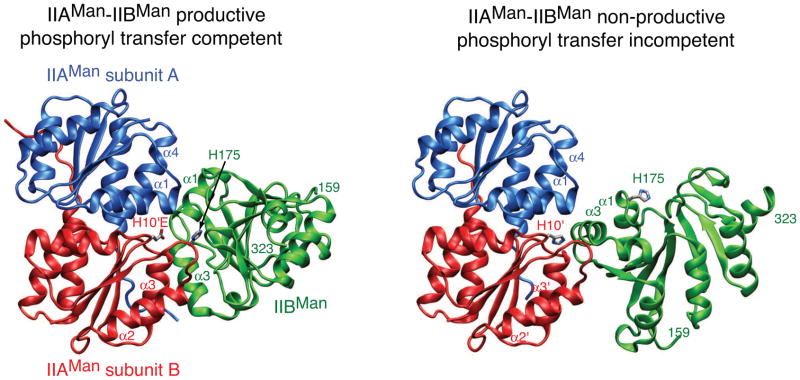

The IIAMan-IIBMan interaction provides an extreme example of a relatively long-lived, highly-populated (around 50% occupancy) and well-defined encounter complex [20], as opposed to the “invisible” sparsely-populated ensemble of transient states seen for the complexes of HPr with EI, IIAMtl and IIAMan [79, 80]. In the case of IIAMan-IIBMan, the intermolecular NOE data report on a mixture of two species comprising a productive, phosphoryl transfer competent complex (Fig. 8, left panel) and a non-productive complex in which the two active site histidines (His10 of IIAMan and His175 of IIBMan) are separated by 25 Å (Fig. 8, right panel). The productive and non-productive complexes are in fast exchange with one another so that only a single set of resonances are observed, but the observed intermolecular NOEs are inconsistent with the existence of a single complex. The structural transition between productive and non-productive complexes involves a 90° rotation coupled to a ~37 Å translation of IIBMan relative to IIAMan. The interaction surface, however, on IIAMan for the non-productive complex comprises a subset of residues located in the central region of the interface in the productive complex. Likewise, the interaction surfaces for the productive and non-productive complexes on IIBMan also partially overlap. Thus, the productive and non-productive complexes are mutually exclusive, as are both of these complexes with the upstream IIAMan-HPr complex.

Fig. 8.

Productive, phosphoryl transfer competent (left) and non-productive, phopshoryl transfer incompetent (right) complexes of IIAMan and IIBMan. Both productive and non-productive complexes are significantly populated in the absence of phosphorylation or mutation of His10 of IIAMan to Glu to mimic the phosphorylated state. The latter mutation shifts the equilibrium almost entirely to the productive complex. The two subunits of IIAMan are shown in blue and red, respectively, and IIBMan is in green. Only a single IIBMan molecule is shown for clarity. Adapted from [20].

The non-productive IIAMan-IIBMan complex (or more accurately intermolecular NOEs attributable to the non-productive complex) can be largely eliminated by introducing a phosphomimetic H10E mutation in IIAMan. The equivalent phosphomimetic His175E in IIBMan, however, has no effect. The selection of the productive complex by IIAMan(H10E) can be attributed to charge neutralization through interaction of the negatively charged carboxylate of H10E (equivalent to phosphorylated His10) with the positively charged guanidino group of Arg172 located at the center of the IIBMan binding surface [20]. This is supported by mutation of Arg172 to Gln which results in a substantial increase in the population of the productive complex; the non-productive complex, however, is not completely eliminated as the mutation still leaves an unfavorable polar residue in the middle of the interface. These observations are consistent with the finding that IIBMan(R172Q) is less efficiently phosphorylated than the wild type by IIAMan [82].

What is the role of the non-productive IIAMan-IIBMan complex? It could represent an extreme example of an encounter complex, where the non-productive complex could facilitate formation of the specific complex in a similar manner as highly transient, diffuse encounter complex ensembles.

Concluding remarks

The complexes of the PTS provide a paradigm for studying protein-protein interactions and understanding the determinants of specificity in a multi-faceted and complex signal transduction system that allows for interactions between many partner proteins. The complexes of the PTS, which range from ~30 to ~150 kDa, have also served as a framework for extending NMR methodology to larger and more complex systems, for establishing integrative hybrid approaches combining RDCs and solution Xray scattering to tackle systems in excess of 100 kDa, and for developing novel biophysical techniques based on NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancement to uncover the existence of transient, spectroscopically “invisible”, sparsely-populated encounter complexes that constitute the first step towards specific complex formation.

There remain two open questions/challenges that still need to be addressed with respect to the structural biology and biophysics of the PTS. The first relates to Enzyme I and the mechanism and dynamics of large-scale interdomain structural rearrangements that must occur during the course of the catalytic cycle. How, for example, are very small local structural changes in the EIC domain upon binding to PEP transmitted to the EIN domain? In the absence of PEP does the open free state coexit with a small population of spectroscopically invisible closed state (cf. Fig. 4), and if so what is the population of the latter, what are the interconversion rates between the species, and how are these populations and rates modulated by different ligands (e.g. the substrate PEP versus the inhibitor α-ketoglutarate both of which bind to the same site on EIC [28]). These questions can largely be addressed by multidimensional hetreonuclear NMR spectroscopy, including the application of relaxation dispersion and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements, but are rendered especially challenging owing to the large size (by NMR standards) of Enzyme I. The second area relates to high resolution structures of the transmembrane sugar transporters (IIC and IID; cf. Fig. 1) of the PTS, their interaction with enzymes IIB, and the mechanism of selective sugar transport across the membrane. While there have been some low resolution electron microscopy (EM) and cysteine cross-linking studies on the IIC transporters from the glucose [83, 84] and mannitol [85, 86] branches, this field remains largely an open book. Encouragingly crystals of IICGlc diffracting to 4.5 Å resolution have been recently obtained [87]. Solving structures of the transmembrane transporters will require extensive biochemical work to obtain either crystals diffracting to high resolution or suitable preparations for single molecule analysis by EM.

Highlights.

Structures of all soluble complexes of the phosphotransferase system have been solved.

NMR methods used to solve structures of large complexes are discussed

The structural basis of specificity in PTS protein-protein complexes is discussed.

Hybrid integrative methods involving NMR and X-ray scattering are highlighted.

Encounter complexes are visualized by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

Acknowledgments

G.M.C. thanks members of his laboratory, past and present, and colleagues who have made major contributions to the work on complexes of the PTS, in particular, D. Garrett, M. Cai, G. Wang, G. Cornilescu, D. Williams, J. Hu, K. Hu, J.-Y. Suh, Y.-S. Jung, C. Tang, J. Iwahara, Y. Takayama, A. Grishaev and C. Schwieters. This work was supported by funds from the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIDDK, and the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the NIH (to G.M.C.).

Glossary

- Heteronuclear NMR

NMR experiments that make use of correlations between different types of NMR active nuclei, such as 1H, 15N and 13C.

- Multidimensional NMR

Experiments that correlate chemical shifts in several dimensions. For example, a 2D 1H-15N correlation experiment correlates the chemical shift of a backbone amide proton with the 15N shift of its directly bonded nitrogen atom via the one-bond 1H-15N scalar coupling. A 2D experiment comprises a preparation pulse, an evolution period during which the nuclear spins are labeled according to their chemical shifts, a mixing period during which the spins are correlated to one another (e.g. through-bond via scalar couplings or through space via the nuclear Overhauser effect), and a detection period. A 3D experiment that correlates chemical shifts in three dimensions is constructed from two 2D experiments by leaving out the detection period of the first 2D experiment and the preparation pulse of the second 2D experiment. Similarly, extension to a 4D experiment which correlates chemical shifts in four dimensions is constructed by combining a 3D experiment with a 2D one using exactly the same procedure.

- Nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)

The NOE detects through-space interactions between protons separated by less than 5 Å and constitutes the mainstay of traditional NMR protein structure determination.

- Residual dipolar couplings (RDC)

RDCs are measured by taking the difference in scalar couplings recorded in aligned and isotropic (i.e. water) media. Examples of aligned media are bicelles and phage. These alignment media generate a very weak force on the protein that results in a small degree of alignment with respect to the magnetic field. As a result dipolar couplings between nuclei, as well as other orientation-dependent interactions, are no longer averaged to zero through Brownian rotational diffusion. The size of the RDC between two directly bonded nuclei is related to the orientation of the vector connecting the two nuclei to the alignment tensor.

- Relaxation dispersion spectroscopy

This is a class of NMR experiment designed to analyze exchange dynamics in the submillisecond to millisecond time scale that is dependent upon differences in chemical shifts between the species. The technique is capable of detecting exchange between an NMR visible major species and a spectroscopically invisible species populated as little as 1%. The experiment yields exchange rates, populations and the chemical shift differences between the species.

- Solution X-ray scattering

Small and wide-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS/WAXS) yield onedimensional profiles of scattering intensity as a function of the scattering vector q (given by 4πsinθ/λ; where 2θ is the angle between the incident beam and the detector and λ the wavelength of the X-rays) [88]. The scattering profiles are determined by the pairwise distances between all atoms in a molecule and therefore contain information on molecular shape and size. Because of the convoluted nature of SAXS/WAXS it is not possible, outside of the very low q range, to extract features of the scattering curve to a particular structure, and it is generally not feasible to derive unique three-dimensional structures from one-dimensional profiles as many models may be compatible with a particular scattering profile. However, direct refinement against SAXS/WAXS data in combination with other experimental restraints, such as those from NMR can be extremely powerful [40, 41, 89–91].

- Small angle neutron scattering (SANS)

The principals of SANS are the same as those for SAXS/WAXS except neutrons instead of X-rays are used. Since the values of the atomic and solvent scattering amplitudes are different for SAXS/WAXS and SANS, the two techniques provide complementary information so that SANS can be used to validate the results of refinement against SAXS/WAXS. Further, contrast-matched SANS on protein complexes in 40.4% D2O in which one component is protonated and the other deuterated enables one to selectively record SANS profiles originating from only one component of the complex.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kundig W, Ghosh S, Roseman S. Phosphate bound to histidine in a protein as an intermediate in a novel phospho-transferase system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;52:1067–1074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.4.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meadow ND, Fox DK, Roseman S. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: glycose phosphotransferase system. Ann Rev Biochem. 1990;59:497–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR. Phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzberg O, Klevit R. Unraveling a bacterial hexose transport pathway. Cuur Op Struct Biol. 1994;4:814–822. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(94)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robillard GT, Broos J. Structure/function studies on the bacterial carbohydrate transporters, enzymes II, of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1422:73–104. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siebold C, Flukiger K, Beutler R, Erni B. Carbohydrate transporters of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) FEBS Lett. 2001;504:104–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02705-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. How phosphotransferase systemrelated protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microniol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feese MD, Comolli L, Meadow ND, Roseman S, Remington SJ. Structural studies of the Escherichia coli signal transducing protein IIAGlc: implications for target recognition. Biochemistry. 1997;36:16087–16096. doi: 10.1021/bi971999e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worthylake D, Meadow ND, Roseman S, Liao DI, Herzberg O, Remington SJ. Three-dimensional structure of the Escherichia coli phosphocarrier protein IIIGlc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10382–10386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao DI, Kapadia G, Reddy P, Saier MH, Jr, Reizer J, Herzberg O. Structure of the IIA domain of the glucose permease of Bacillus subtilis at 2.2 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9583–9594. doi: 10.1021/bi00104a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Montfort RL, Pijning T, Kalk KH, Hangyi I, Kouwijzer ML, Robillard GT, Dijkstra BW. The structure of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase IIAmannitol reveals a novel fold with two conformations of the active site. Structure. 1998;6:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunn RS, Markovic-Housley Z, Genovesio-Taverne JC, Flukiger K, Rizkallah PJ, Jansonius JN, Schirmer T, Erni B. Structure of the IIA domain of the mannose transporter from Escherichia coli at 1.7 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:502–511. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sliz P, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Pai EF. The structure of enzyme IIAlactose from Lactococcus lactis reveals a new fold and points to possible interactions of a multicomponent system. Structure. 1997;5:775–788. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang C, Williams DC, Jr, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Solution structure of enzyme IIAChitobiose from the N,N′-diacetylchitobiose branch of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11770–11780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legler PM, Cai M, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the cytoplasmic B domain of the mannitol transporter IImannitol of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39115–39121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh JY, Tang C, Cai M, Clore GM. Visualization of the phosphorylated active site loop of the cytoplasmic B domain of the mannitol transporter IIMannitol of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system by NMR spectroscopy and residual dipolar couplings. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Montfort RL, Pijning T, Kalk KH, Reizer J, Saier MH, Jr, Thunnissen MM, Robillard GT, Dijkstra BW. The structure of an energy-coupling protein from bacteria, IIBcellobiose, reveals similarity to eukaryotic protein tyrosine phosphatases. Structure. 1997;5:217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ab E, Schuurman-Wolters GK, Nijlant D, Dijkstra K, Saier MH, Robillard GT, Scheek RM. NMR structure of cysteinyl-phosphorylated enzyme IIB of the N,N′-diacetylchitobiose-specific phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:993–1009. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai M, Williams DC, Jr, Wang G, Lee BR, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM. Solution structure of the phosphoryl transfer complex between the signal-transducing protein IIAGlucose and the cytoplasmic domain of the glucose transporter IICBGlucose of the Escherichia coli glucose phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25191–25206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu J, Hu K, Williams DC, Jr, Komlosh ME, Cai M, Clore GM. Solution NMR structures of productive and non-productive complexes between the A and B domains of the cytoplasmic subunit of the mannose transporter of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11024–11037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schauder S, Nunn RS, Lanz R, Erni B, Schirmer T. Crystal structure of the IIB subunit of a fructose permease (IIBLev) from Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:591–602. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orriss GL, Erni B, Schirmer T. Crystal structure of the IIBSor domain of the sorbose permease from Klebsiella pneumoniae solved to 1.75 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seok YJ, Sondej M, Badawi P, Lewis MS, Briggs MC, Jaffe H, Peterkofsky A. High affinity binding and allosteric regulation of Escherichia coli glycogen phosphorylase by the histidine phosphocarrier protein, HPr. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26511–26521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterkofsky A, Reizer A, Reizer J, Gollop N, Zhu PP, Amin N. Bacterial adenylyl cyclases. Progr Nucl Acids Mol Biol. 1993;44:31–65. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novotny MJ, Frederickson WL, Waygood EB, Saier MH., Jr Allosteric regulation of glycerol kinase by enzyme IIIGlc of the phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:810–816. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.810-816.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam TW, Cho SH, Shin D, Kim JH, Jeong JY, Lee JH, Roe JH, Peterkofsky A, Kang SO, Ryu S, et al. The Escherichia coli glucose transporter enzyme IICBGlc recruits the global repressor Mlc. EMBO J. 2001;20:491–498. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seitz S, Lee SJ, Pennetier C, Boos W, Plumbridge J. Analysis of the interaction between the global regulator Mlc and EIIBGlc of the glucose-specific phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10744–10751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venditti V, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Structural basis for Enzyme I inhibition by α-ketoglutarate. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1232–1240. doi: 10.1021/cb400027q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doucette CD, Schwab DJ, Wingreen NS, Rabinowitz JD. α-ketoglutarate coordinates carbon and nitrogen utilization via enzyme I inhibition. Nature Chem Biol. 2011;7:894–901. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao DI, Silverton E, Seok YJ, Lee BR, Peterkofsky A, Davies DR. The first step in sugar transport: crystal structure of the amino terminal domain of enzyme I of the E. coli PEP: sugar phosphotransferase system and a model of the phosphotransfer complex with HPr. Structure. 1996;4:861–872. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia Z, Quail JW, Waygood EB, Delbaere LT. The 2.0-A resolution structure of Escherichia coli histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr. A redetermination. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22490–22501. doi: 10.2210/pdb1poh/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herzberg O, Reddy P, Sutrina S, Saier MH, Jr, Reizer J, Kapadia G. Structure of the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr from Bacillus subtilis at 2.0-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2499–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teplyakov A, Lim K, Zhu PP, Kapadia G, Chen CC, Schwartz J, Howard A, Reddy PT, Peterkofsky A, Herzberg O. Structure of phosphorylated enzyme I, the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system sugar translocation signal protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16218–16223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607587103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marquez J, Reinelt S, Koch B, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Scheffzek K. Structure of the full-length enzyme I of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32508–32515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberholzer AE, Schneider P, Siebold C, Baumann U, Erni B. Crystal structure of enzyme I of the phosphoenolpyruvate sugar phosphotransferase system in the dephosphorylated state. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33169–33176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.057612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittekind M, Rajagopal P, Branchini BR, Reizer J, Saier MH, Jr, Klevit RE. Solution structure of the phosphocarrier protein HPr from Bacillus subtilis by twodimensional NMR spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1363–1376. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Nuland NAJ, Hangyi IW, Vanschaik RC, Berendsen HJC, Vangunsteren WF, Scheek RM, Robillard GT. The high-resolution structure of the histidinecontaining phosphocarrier protein HPr from Escherichia coli determined by restrained molecular dynamics from nuclear magnetic resonance nuclear Overhauser effect data. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:544–559. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Nuland NAJ, Boelens R, Scheek RM, Robillard GT. High-resolution structure of the phosphorylated form of the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr from Escherichia coli determined by restrained molecular dynamics from NMR NOE data. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:180–193. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrett DS, Seok YJ, Liao DI, Peterkofsky A, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Solution structure of the 30 kDa N-terminal domain of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system by multidimensional NMR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2517–2530. doi: 10.1021/bi962924y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwieters CD, Suh JY, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Takayama Y, Clore GM. Solution structure of the 128 kDa enzyme I dimer from Escherichia coli and its 146 kDa complex with HPr using residual dipolar couplings and small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13026–13045. doi: 10.1021/ja105485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takayama Y, Schwieters CD, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Combined use of residual dipolar couplings and solution X-ray scattering to rapidly probe rigid-body conformational transitions in a non-phosphorylatable active-site mutant of the 128 kDa enzyme I dimer. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:424–427. doi: 10.1021/ja109866w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrett DS, Seok YJ, Peterkofsky A, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Solution structure of the 40,000 Mr phosphoryl transfer complex between the N-terminal domain of enzyme I and HPr. Nature Struct Biol. 1999;6:166–173. doi: 10.1038/5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clore GM. Accurate and rapid docking of protein-protein complexes on the basis of intermolecular nuclear overhauser enhancement data and dipolar couplings by rigid body minimization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9021–9025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Internal coordinates for molecular dynamics and minimization in structure determination and refinement. J Magn Reson. 2001;152:288–302. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornilescu G, Lee BR, Cornilescu CC, Wang G, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM. Solution structure of the phosphoryl transfer complex between the cytoplasmic A domain of the mannitol transporter IIMannitol and HPr of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42289–42298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Determining the structures of large proteins and protein complexes by NMR. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:22–34. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang G, Louis JM, Sondej M, Seok YJ, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM. Solution structure of the phosphoryl transfer complex between the signal transducing proteins HPr and IIAglucose of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. EMBO J. 2000;19:5635–5649. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams DC, Jr, Cai M, Suh JY, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM. Solution NMR structure of the 48-kDa IIAMannose-HPr complex of the Escherichia coli mannose phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20775–20784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501986200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung YS, Cai M, Clore GM. Solution structure of the IIAChitobiose-HPr complex of the N,N′-diacetylchitobiose branch of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23819–23829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.371492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suh JY, Cai M, Williams DC, Jr, Clore GM. Solution structure of a post-transition state analog of the phosphotransfer reaction between the A and B cytoplasmic domains of the mannitol transporter IIMannitol of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8939–8949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung YS, Cai M, Clore GM. Solution structure of the IIAChitobiose-IIBChitobiose complex of the N,N′-diacetylchitobiose branch of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4173–4184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nam TW, Jung HI, An YJ, Park YH, Lee SH, Seok YJ, Cha SS. Analyses of Mlc-IIBGlc interaction and a plausible molecular mechanism of Mlc inactivation by membrane sequestration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3751–3756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709295105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herzberg O. An atomic model for protein-protein phosphoryl group transfer. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24819–24823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Begley GS, Hansen DE, Jacobson GR, Knowles JR. Stereochemical course of the reactions catalyzed by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:glucose phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5552–5556. doi: 10.1021/bi00265a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller EG, Khandekar SS, Knowles JR, Jacobson GR. Stereochemical course of the reactions catalyzed by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:mannitol phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6892–6896. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hollfelder F, Herschlag D. The nature of the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer. Hydrolysis of O-aryl phosphorothioates by alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12255–12264. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohwer JM, Meadow ND, Roseman S, Westerhoff HV, Postma PW. Understanding glucose transport by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:glycose phosphotransferase system on the basis of kinetic measurements in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34909–34921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suh JY, Iwahara J, Clore GM. Intramolecular domain-domain association/dissociation and phosphoryl transfer in the mannitol transporter of Escherichia coli are not coupled. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3153–3158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609103104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]