Abstract

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) plasma membrane transporters influence synaptic transmission by high-affinity, Na+-dependent transport processes. The cDNA clone, GAT-1, encodes a high-affinity Na+- and Cl−-dependent GABA plasma membrane transporter, which has kinetic and pharmacological properties similar to those of high-affinity GABA uptake systems associated with neurons. The present study evaluates the distribution and cellular localization of this putative neuronal GABA transporter by RNA blot hybridization and in situ hybridization histochemistry in the rat retina. Northern blot hybridization analysis of total retinal and cerebellar RNA extracts demonstrated a single band of hybridization at 4.2 kilobases. GABA transporter mRNA is expressed by numerous cells that are distributed to the proximal inner nuclear layer and the ganglion cell layer and by a few cells located in the inner plexiform layer. Double label studies combining the retrograde transport of the fluorescent dye Fluorogold from the superior colliculus to identify ganglion cells and in situ hybridization histochemistry demonstrated that most GAT-1 mRNA-containing cells in the ganglion cell layer are displaced amacrine cells, although some ganglion cells containing GAT-1 mRNA were visualized. In freshly dissociated retinal cell preparations, the GAT-1 RNA signal is strong in neurons and weak to moderate in specialized glial cells called Müller cells. Müller cells were identified by both their morphology and the presence of the selective Müller cell marker cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein. Only hackground labeling is seen with the sense GAT-1 RNA probe in both tissue sections and dissociated retinal cell preparations. These findings demonstrate that GAT-1 mRNA is expressed in both the retina and brain. In the retina, this transporter is predominantly localized to amacrine, displaced amacrine and interplexiform cells, and some ganglion cells. This transporter mRNA is also expressed by Müller cells but at a lower level than by neurons. These observations indicate that GABA transport by GAT-1 plasma membrane transporters in the retina is mediated by both neurons and glia cells.

Keywords: GABA uptake, neurotransmitter transporter, amacrine cells, glial cells, Müller cells

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the predominant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nervous system. Specific Na+-and Cl−-dependent, high-affinity GABA transporters are located in the plasma membrane of both GABA-containing neurons and glial cells (Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Schousboe, 1981; Kanner and Shuldiner, 1987; Kanner and Bendahan, 1990; Radian et al., 1990). These transporters have several possible functional roles. For instance, they are likely to inactivate GABA’s action in synaptic transmission by removing it from the vicinity of GABA receptors into presynaptic terminals and glial cells (Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Schousboe, 1981; Isaacson et al., 1993). In presynaptic terminals GABA may be recycled into synaptic vesicles for subsequent vesicular release, whereas in glial cells it is rapidly metabolized (Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Schousboe, 1981). In addition, GABA transporters mediate the electrogenic release of GABA in a Ca2+-independent, nonvesicular manner upon membrane depolarization in some cells (Schwartz, 1987; Kamermans and Werblin, 1992), and this may be a general mechanism for GABA release in the nervous system (Attwell et al., 1993).

Four cDNAs encoding plasma membrane transporters that utilize GABA as a substrate have now been localized to the rodent nervous system (Guastella et al., 1990; Borden et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1992; López-Corcuera et al., 1992). GAT-1 is a high affinity GABA transporter that has been isolated from both the rodent and human nervous system (Guastella et al., 1990; Nelson et al., 1990; Liu et al., 1992). The rat GAT-1 cDNA clone encodes a predicted protein of 599 amino acids, and hydropathy analysis indicates that it is likely to have 11 or 12 membrane spanning regions (Guastella et al., 1990). Expression studies using the rat GAT-1 cDNA clone in Xenopus oocytes and in mammalian cell lines show that this transporter is characterized by high-affinity, Na+-and Cl−-dependent GABA uptake. This uptake is strongly inhibited by cis-3-aminocyclohexane carboxylic acid (ACHC), less strongly inhibited by 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (DABA), and not inhibited by β-alanine (Guastella et al., 1990; Clark et al., 1992; Keynan et al., 1992). These kinetic and pharmacological properties are similar to those of high-affinity GABA uptake systems classically described for neuronal preparations and not for glial preparations (Beart et al., 1972; Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Bowery et al., 1976; Neal and Bowery, 1977; Kanner and Bendahan, 1990; Mabjeesh et al., 1992). In addition, GAT-1 mRNA is localized to neurons in the central nervous system (Brecha et al., 1992). The other recently cloned rat GABA transporters, GAT-2 and GAT-3 (or GAT-B), share about 50% amino acid sequence homology with GAT-1 (Borden et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1992). These transporters, when expressed in heterologous cell systems, differ significantly in their pharmacological properties from GAT-1, with very little or no inhibition of GABA uptake by ACHC but strong inhibition of GABA uptake by β-alanine (Borden et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1992). In addition, a GABA transporter called GAT-2, which is most similar in its nucleotide sequence to a glycine betaine transporter identified in dog kidney, has been reported in the mouse nervous system (López-Corcuera et al., 1992; Yamauchi et al., 1992). This GABA transporter also differs in its kinetic and pharmacological properties from rat and mouse GAT-1 (Guastella et al., 1990; López-Corcuera et al., 1992). These recent molecular cloning findings with earlier kinetic and pharmacological observations (Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Wood and Sidhu, 1987; Kanner and Bendahan, 1990) indicate a heterogeneity of GABA transporters in the nervous system.

The mammalian retina contains Na+-dependent GABA uptake systems (Starr and Voaden, 1972; Goodchild and Neal, 1973; Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Neal, 1976; Redburn, 1977; see Brecha, 1983; Yazulla, 1986; for reviews), which are associated with amacrine and interplexiform cells and with radially oriented glial cells that are known as Müller cells, as indicated by uptake-autoradiographic and pharmacological approaches (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974; Ehinger, 1977; Yazulla, 1986; O’Malley et al., 1992). The kinetic and pharmacological characteristics of these uptake systems, as well as the cellular localization patterns of GABA and GABA analogue uptake, support the presence of multiple GABA transporters in the retina (Agardh and Ehinger, 1982; Goodchild and Neal, 1973; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Bruun et al., 1974; Iversen and Kelly, 1975; Ehinger, 1977; Neal and Bowery, 1977; Bauer and Ehinger, 1978; Cunningham et al., 1981; Pourcho, 1981; Blanks and Roffler-Tarlov, 1982; Hendrickson et al., 1985; Yazulla, 1986).

The distribution and localization of GABA plasma membrane transporter proteins or their mRNAs in the mammalian retina are unknown, although these transporters are presumably expressed by GABAergic neurons and Müller cells (Yazulla, 1986). In addition, it is unknown if structurally different transporters are expressed by distinct retinal cells and, finally, if these transporters are the same or different from GABA plasma membrane transporters expressed elsewhere in the nervous system. The present study provides the first direct evidence of the cellular localization of a recently described high-affinity ACHC-sensitive GABA transporter mRNA called GAT-1 (Guastella et al., 1990) in the rat retina by using blot hybridization and in situ hybridization histochemistry. A brief description of preliminary results has been presented in abstract form (Weigmann and Brecha, 1991).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult albino rats (Sprague-Dawley; Harlan, San Diego, CA), weighing 180–250 g were used in these studies. They were fed and housed under regular conditions with a 12 hour light-dark schedule. Care and handling of animals were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the VAMC—West Los Angeles in accordance with all NIH guidelines.

Northern analysis

Northern blot hybridization experiments used an antisense RNA probe, which was synthesized from a 4.2 kilobase, full-length rat GABA transporter cDNA clone (GAT-1; Guastella et al., 1990) by using T3 RNA polymerase in the presence of α-32P-uridine triphosphate (3,000 Ci/mmol; NEN/DuPont, Wilmington, DE) at a specific activity of 8–10 × 108 cpm/μg, as previously described (Brecha et al., 1989; Sternini et al., 1989). Rats were anesthetized with Halothane (Halocarbon Laboratories, Inc; North Augusta, GA) and decapitated. The retina, cerebellum, and liver were rapidly dissected, frozen on dry ice, weighed, and stored at −70°C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted by a modified single step RNA isolation (Chirgwin et al., 1979), separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde, and transferred to a Nybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The RNA blot was preincubated in hybridization buffer [50% formamide, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% Ficoll, 0.1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), 0.05 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 3.75 mM Na2P2O7, 1% (vol/vol) sarcosyl, 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate containing 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml] at 65°C overnight and then incubated in the same buffer with 3 × 106 cpm of 32P-GAT-1 RNA per milliliter at 65°C for 18 hours. Blots were washed under stringent conditions in a final wash of 0.1 × SSPE (0.18 M NaCl, 0.01 M NaH2PO4, 0.001 M EDTA) with 0.1% sarcosyl at 70°C, dried, and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film at −70°C with intensifying screens for 2 hours to 4 days. The relative amount of RNA loaded onto the gel was determined by reprobing the membrane with a human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) RNA probe (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as described above. The human G3PDH RNA probe hybridizes with rat G3PDH mRNA.

In situ hybridization experiments

Rats were anesthetized with 30% chloral hydrate and perfused through the heart with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (4% PFA) in PBS. The eyes were removed, the anterior segments were cut away, and the retinas were dissected and postfixed in 4% PFA/PBS at 4°C until processing.

Antisense and sense GABA transporter RNA probes were prepared from the GAT-1 cDNA by in vitro transcription using T3 or T7 polymerase and 35S-uridine triphosphate (1,200 Ci/mmol; NEN/DuPont) at a specific activity of 3–5 × 108 cpm/μg (Brecha et al., 1989; Sternini et al., RNA probes used for the in situ hybridization experiments were either full length or cleaved to 400–500 nuclealtides limited alkaline hydrolysis (Cox et al., 1984).

The in situ hybridization protocol is similar to described in our previous publications (Brecha et al., 1989; Sternini et al., 1989). Whole retinas or pieces were washed withglycine (0.75 mg/ml)/PBS, 1 × SSC (0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Na citrate) and incubated in proteinase K (1 μg/ml) for minutes at 37°C, followed by triethanolamine, pH 8.0, plus acetic anhydrate for 10 minutes and then were washed in 2× SSC. Retinas were prehybridized free floating at 37°C for 2 hours with hybridization buffer [25 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 0.75 M NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 1 × Denhardt’s solution (0.02% PVP, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% BSA), 50% deionized formamide, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 250 μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA, and 250 μg/ml polyadenylic acid]. Retinas were then incubated in the hybridization mixture with 5% dextran sulfate containing 35S-GAT-1 sense or antisense RNA (0.1 ng/μl) overnight at 52–55°C. Sections were then washed in 4 × SSC containing 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10 mM Na thiosulfate, incubated in pancreatic RNase A (50 μg/ml) for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed again with SSC buffer at increasing stringency to a final wash of 0.1 × SSC at 60°C or 65°C, and in some experiments at 70°C. Retinas were then washed overnight in 0.1 × SSC at room temperature, dehydrated through graded ethanols and butanol, and embedded in diethylene glycol distearate (DGD; Poly-sciences; Warrington, PA; Porrello et al., 1991). Retinas were subsequently cut at 3 μm, the DGD was removed from the sections with a graded series of ethanols and butanol, and the sections were then processed for autoradiography by using Kodak NTB-2 liquid photographic emulsion diluted 1:1 with distilled water. Autoradiograms were developed in Kodak D-19 and fixed in Kodak fixer after different exposure periods (10–60 days). Sections were then counter-stained with toluidine blue, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped.

Retrograde transport studies

Rats were anesthetized with Nembutal (60 mg/kg), and bilateral stereotaxic injections of 0.5 μl of 1% Fluorogold (Fluorochrome, Englewood, CO) in 0.9% NaCl were made into the superior colliculus with a 1 μl Hamilton syringe. After a 4–8 day survival period, the rats were anesthetized with 30% chloral hydrate and perfused through the heart with PBS followed by 4% PFA in PBS. The eyes were removed, the anterior segments were cut away, and the retinas were dissected and postfixed in 4% PFA/PBS with 30% sucrose at 4°C until they were sectioned at 10 μm with a cryostat. Sectioned retinas were stored at −20°C until processing. The brain was removed, and the locations of the injection sites in the superior colliculus were verified by both gross inspection and analysis of transverse sections through the midbrain.

Retinal sections were processed for in situ hybridization histochemistry as described above for the whole retinas. The RNA probe was used at a concentration of 0.1 ng/μl, and a total of 40 μl of hybridization buffer was applied each slide.

Retinal dissociation

Retinal cells were separated by a dissociation procedure which is described in detail in previous publications (Sarthy and Lam, 1979; Huba and Hoffman, 1988). In brief, rats were anesthetized with Halothane and decapitated, and the eyes were removed. The retinas were dissected in normal Hanks balanced salt solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), incubated in normal Hanks solution containing 0.1% collagenase (1,610 units/mg; Sigma) and 0.04% hyaluronidase (760 units/mg; Sigma) for 18 minutes at 37°C, then incubated in Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks solution with 2 mM L-cysteine, 2.5 mM EGTA, and 0.025% papain (11 units/mg; Sigma) for 22 minutes at 37°C. Retinal pieces were washed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium and Ham’ss nutrient mixture F-12 (DME; Sigma) and 0.02% DNAse (12,100 units/mg; Sigma), then triturated through a Pasteur pipette five or six times in DME. The papain digestion and trituration were usually repeated once. The cells were gently spun at 50g for 5 minutes and washed again in DME and DNase, and two or three drops of the cell suspension were placed onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides. The cells were allowed to settle for 30 minutes and then fixed by adding several drops of 4% PFA in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing in PBS, the dissociated cells were dehydrated and stored until processing.

The dissociated cells were rehydrated and processed for in situ hybridization histochemistry like the whole retinas, except for a reduction of the proteinase K incubation to 7 minutes. They were incubated with 40 μl of hybridization buffer containing 0.1 ng/μ1 of the RNA probe.

To determine the specificity of hybridization, whole retinas, retinal pieces and sections, and dissociated cell preparations were incubated with the sense RNA probe.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies used a rabbit polyclonal antiserum directed to cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP; Bunt-Milam and Saari, 1983) to identify Müller cells. Following the in situ hybridization histochemical procedure, dissociated retinal cells attached to slides were incubated with primary antibody at 1:200 with 1% BSA and 10% normal goat serum in 0.5% Triton X-100/PB for 12–18 hours at 4°C and processed with an avidin-biotin technique (Casini and Brecha, 1991). The dissociated cell preparations were incubated in biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG, washed, incubated in avidin-biotin peroxidase complex, and washed again. They were then incubated in 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma), followed by DAB with 0.01% H2O2, washed, dehydrated, and then processed by autoradiographic procedures (as described above).

Specificity of the immunoreactive staining was assessed by incubating adjacent sections in nonimmune rabbit serum. However, control experiments cannot exclude the possibility of cross-reactivity with other substances. The terms CRALBP-immunoreactive or containing are used to describe the staining.

Cell counts

A semiquantitative assessment was made of the hybridization signal in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) to estimate the number of cells containing GAT-1 mRNA. Labeled cells were defined as having five times the number of silver grains over their cell bodies than a comparably sized area in the inner plexiform layer (IPL). This arbitrary criterion was chosen to insure that labeled cells could be clearly distinguished from adjacent nonspecifically labeled cells. Cells were counted from 3 μm thick sections of retinas embedded in DGD, which were exposed for 38 days and counterstained with Toluidine Blue. Sections measuring a minimum of 10 mm in length were counted.

RESULTS

Northern blot analysis

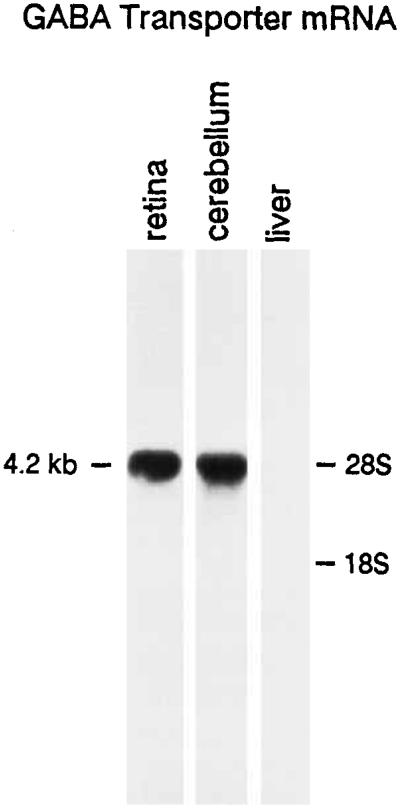

The GABA transporter RNA probe (GAT-1) detected a single band at about 4.2 kilobases in RNA extracted from the retina and cerebellum (Fig. 1) in agreement with previous reports (Guastella et al., 1990; Nelson et al., 1990; Borden et al., 1992). The density of the retinal mRNA signal is similar to the cerebellar mRNA signal, and it is relatively greater compared to other central nervous system regions (Brecha and Weigmann, unpublished). The relative amounts of RNA loaded onto the gel are comparable for the retina and cerebellum, as determined from the density of the G3PDH mRNA signal. G3PDH is a ubiquitously expressed “housekeeping gene” found in many tissues (Tso al., 1985). GABA transporter transcripts are not detected in RNA extracted from the liver, which served as a negative control (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Northern blot hybridization using the rat antisense GAT-1 RNA probe with retinal, cerebellar, and liver RNA. A 4.2 kilobase transcript was identified in the retina and cerebellum. Ten micrograms of total RNA from the retina and cerebellum and 20 μg of total RNA from the liver were loaded in the appropriate lanes. RNA size markers were run in a parallel lane and stained with ethidium bromide. kb, kilobases; 18S, 18S RNA; 28S, 28S RNA.

Distribution of GABA transporter mRNA in retinal sections

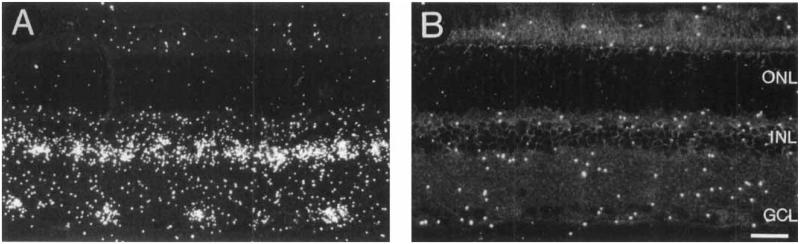

GAT-1 mRNA is abundant in the proximal inner nuclear layer (INL) and GCL in all retinal regions (Figs. 2, 3). Identical hybridization patterns are observed with both partially digested and full-length RNA probes. Labeling is not associated with endothelial cells lining blood vessels nor with astrocytes, which are mainly located in the ganglion cell axon layer (Dixon and Eng, 1981; Schnitzer, 1988). Only background labeling is observed over the distal INL, outer plexiform layer and outer nuclear layer, and in sections incubated with the sense RNA probe (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Darkfield photomicrograph of a 3 μm retinal section incubated with 35S-GAT-1 RNA in the antisense (A) or sense (B) orientation. A: Prominent labeling is observed in the proximal inner nuclear layer (INL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL). B: Control section showing background labeling. ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 25 μm.

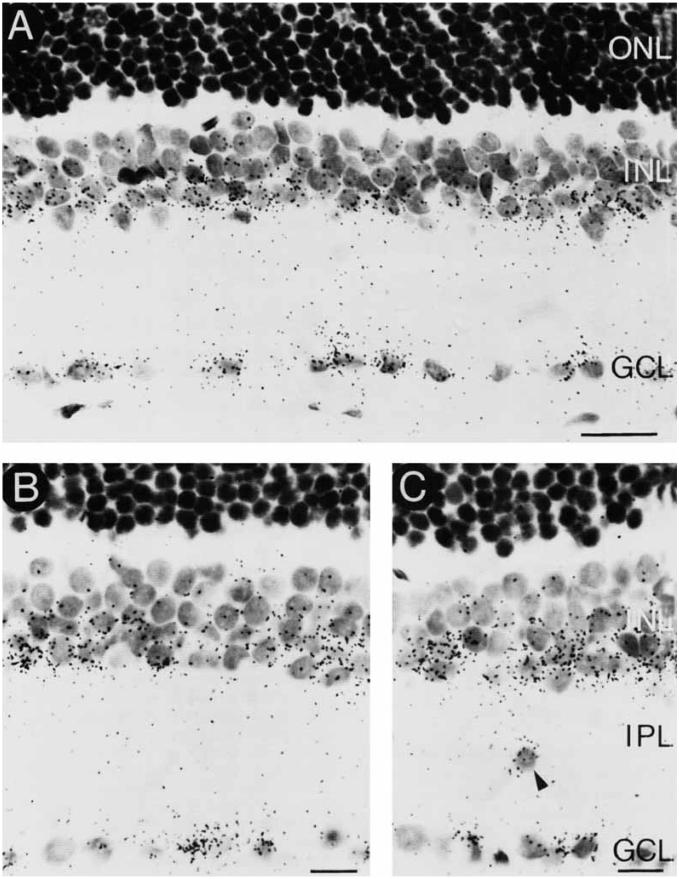

Fig. 3.

Cellular localization of GAT-1 mRNA. Brightfield photomicrographs of thin sections (3 μm) incubated with 35S-GAT-1 RNA. The labeling pattern shown in Figure 2 and in A–C of this figure indicates that amacrine and displaced amacrine cells, interplexiform cells, and perhaps ganglion and Müller cells express GAT-1 mRNA. C: A labeled interstitial cell is indicated by the arrowhead. IPL, inner plexiform layer. Scale bars = 20 μm in A, 10 μm in B and C.

In all retinal regions, GAT-1 mRNA is localized to numerous small cell bodies, which are usually confined to the first two rows of cells of the proximal INL (Fig. 3). The number and distribution of labeled cells in the proximal INL suggest that they are amacrine cells. Some labeled cells also may be interplexiform cells, since their cell bodies are located in the proximal INL at the IPL border. The hybridization pattern in the INL also indicates that Müller cells, whose cell bodies are located in the middle of this layer and are mixed with amacrine and bipolar cells, may express GAT-1 mRNA. However, positive identification of Müller cells is difficult in retinal sections due to light counterstaining and the destruction of cytological detail from the treatment of the retina with RNase A. Therefore, we conducted additional cell dissociation experiments (below) to determine if GAT-1 mRNA is expressed by these cells. Finally, some strongly labeled cells are present in the inner plexiform layer (IPL; Fig. 3C. These labeled cells are likely to be amacrine cells, which are sometimes referred to as displaced amacrine cells or as interstitial cells.

In the GCL, there are numerous strongly labeled cells (Figs. 2, 3). Most of these neurons are similar in appearance to the labeled amacrine cells observed in the proximal INL and IPL, suggesting that they are displaced amacrine cells. A few larger cells are also labeled, and they have the appearance of ganglion cells. Counts of the number of labeled cell bodies (defined by having five times the grain density of a comparable area in the IPL) demonstrate that labeled cells make up about 51% (186/365) of the total number of cells in the GCL. This estimate is similar to an earlier estimate of the number of displaced amacrine cells in the rat retina (Perry, 1981). Together, these observations indicate that on the basis of cell appearance and number, most of the labeled cells in the GCL-containing GAT-1 mRNA are displaced amacrine cells.

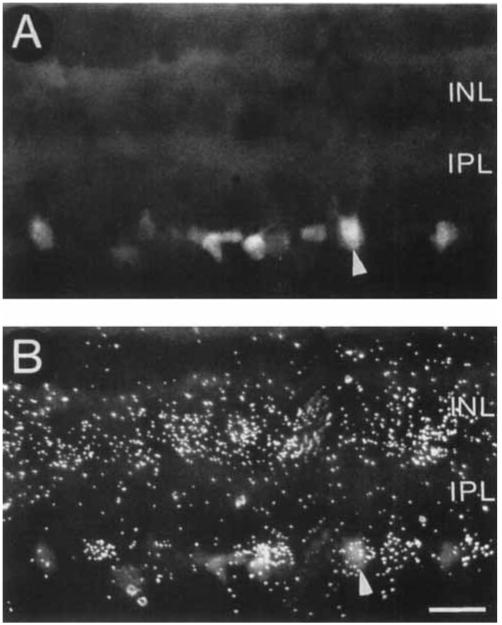

Numerous ganglion cells of all sizes are heavily labeled following the bilateral injections of Fluorogold into the superficial layers of the superior colliculus, confirming earlier retrograde transport studies (Caruso et al., 1989). The double label studies employing both the retrograde transport of Fluorogold and in situ hybridization histochemistry show that the majority of ganglion cells containing Fluorogold do not contain GAT-1 mRNA (Fig. 4). However, a few Fluorogold-labeled ganglion cells containing GAT-1 mRNA are observed in the GCL. These observations indicate that the majority of cells in the GCL-containing GAT-1 mRNA are displaced amacrine cells.

Fig. 4.

Localization of GAT-1 mRNA in a section from the Fluorogold retrograde transport-in situ hybridization experiments. A: Fluorescence photomicrograph showing Fluorogold-containing ganglion cells following an injection of Fluorogold into the superficial layers of the superior colliculus. B: Double exposed photomicrograph (fluorescence and darkfield) of the same field as in A showing that most Fluorogold-containing ganglion cells do not contain GAT-1 mRNA, indicating that most GAT-1-containing cells in the GCL are displaced amacrine cells. However, some ganglion cells contain GAT-1 mRNA. A double labeled ganglion cell is indicated by the arrowhead. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Localization of GABA transporter mRNA in dissociated retinal cell preparations

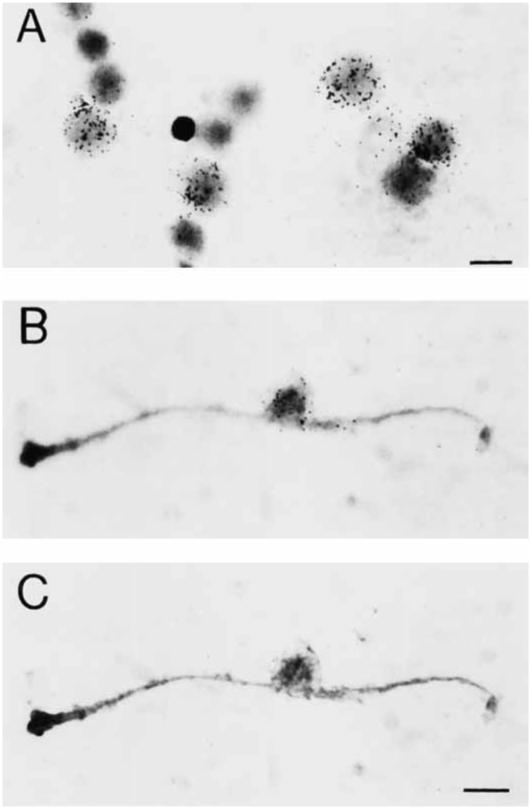

In freshly dissociated retinal cell preparations, GAT-1 mRNA is abundant in many small and medium cells (Fig. 5A). GAT-1 mRNA is also localized to all Müller cells (Fig. 5B,C). Müller cells were identified by either a dark staining nucleus and lightly staining, thick, long processes when stained by toluidine blue or the presence of CRALBP immunoreactivity. CRALBP is a retinoid that is localized to Müller cells and retinal pigment epithelium cells (Bunt-Milam and Saari, 1983). The GAT-1 mRNA labeling associated with Müller cells is mainly located over the cell body, and hybridization signal is rarely located over cell processes. Müller cells have a low to moderate level of GAT-1 mRNA compared to adjacent labeled neurons in the same preparations.

Fig. 5.

Expression of GAT-1 mRNA in freshly dissociated retinal cell preparations. Prominent labeling is observed over small and medium-sized round cells (A). Low to moderate labeling is seen over Müller cells (B,C). Müller cells are identified by their characteristic morphology and their expression of CRALBP immunoreactivity. A was stained with toluidine blue; B and C were processed for immunohistochemistry with an antibody directed to CRALBP. The photomicrographs in A and B are focused on the silver grains overlying the neurons and the Müller cell, respectively. C is focused on the Müller cell. Scale bars = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

These investigations demonstrate that GAT-1 mRNA is present in the rat retina, and it is localized to amacrine, ganglion, and Müller cells. These findings extend biochemical, pharmacological, and uptake-autoradiographic observations, which have indicated the presence, of a Na+-dependent, high-affinity GABA uptake system in the rat retina (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Starr and Voaden, 1972; Goodchild and Neal, 1973; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974; Neal, 1976).

The mRNA detected in the retina is identical in size to GAT-1 mRNA reported in the central nervous system (Guastella et al., 1990; Nelson et al., 1990; Brecha and Weigmann, unpublished observations). GAT-1 mRNA is abundantly expressed by neurons and lightly to moderately expressed by Müller cells. The expression of GAT-1 mRNA in the retina and its localization to these cell types are demonstrated by the single band of hybridization in the Northern blot of the retina and the presence of specific hybridization signal in tissue sections following high stringency wash conditions of 0.1 × SSC at 60°C, 65°C, and 70°C. A further indication that GAT-1 RNA signal in the retina is due to the presence of GAT-1 mRNA and not due to cross-hybridization with other related mRNA is the lack of specific hybridization signal in rat retinal sections incubated with a 700 base pair rabbit GAT-1 RNA probe that has about 85% homology to the corresponding region of rat GAT-1 mRNA (Brecha, Guastella, and Weigmann, unpublished observations). However, these experimental approaches do not completely rule out the possibility of the existence of highly homologous transporters in the retina, perhaps due to alternative splicing, that cross-react with the GAT-1 probes.

Neuronal expression of the GAT-1 transporter

The present findings are consistent with the expression of GAT-1 mRNA in amacrine, displaced amacrine, and interplexiform cells. The identification of these cells is based on their appearance and known distribution in the proximal INL, IPL, and GCL. The double label studies involving the retrograde transport of Fluorogold and in situ hybridization also indicate that the majority of GAT-1 mRNA-containing cells in the GCL are displaced amacrine cells. Further evidence that displaced amacrine cells express this GABA transporter mRNA derives from the close match in their estimated number and the estimated number of displaced amacrine cells determined by other methods (Perry, 1981). There is a general correspondence of the patterns of GAT-1 mRNA hybridization, GABA immunostaining (Mosinger et al., 1986; Caruso et al., 1989), and GABA synthetic enzyme L-glutamate decarboxy1ase67 (GAD67) mRNA hybridization and immunostaining (Brandon, 1985; Brecha et al., 1991). Together, these observations indicate that the same group of cells that expresses GAT-1 mRNA is also likely to express GABA and GAD67; however, double label experiments are needed to determine their exact relationships. Finally, the experiments utilizing the retrograde transport of Fluorogold from the superior colliculus demonstrate that a few ganglion cells contain GAT-1 mRNA. The GAT-1 mRNA-containing ganglion cells are likely to correspond to the small percentage of GABA-immunoreactive ganglion cells that were identified in an earlier double label retrograde transport study that employed antibodies directed to GABA (Caruso et al., 1989).

GAD- and GABA-immunoreactive, and GAD67 mRNA-containing horizontal cells are a feature of some mammalian retinas (Mosinger et al., 1986; Pourcho and Owczarzak, 1989; Sarthy and Fu, 1989; Wässle and Chun, 1989; Grünert and Wässle, 1990). However, in the adult rat retina, GABA uptake has never been reported in horizontal cells (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974). In addition, most investigations report that horizontal cells do not contain GAD and GABA immunoreactivity or GAD65 and GAD67 mRNAs (Vaughn et al., 1981; Brandon, 1985; Mosinger et al., 1986; Caruso et al., 1989; Brecha et al., 1991; Brecha, unpublished observations). GAT-1 mRNA also is not detected in these cells, further suggesting that in the rat retina horizontal cells are not GABAergic. However, the possibility of a very low level of expression of GAT-1 mRNA in rat horizontal cells, which cannot be detected by in situ hybridization histochemistry, or the expression of one of the other recently described GABA plasma membrane transporters (Borden et al., 1992) by horizontal cells cannot be discounted.

Glial expression of the GAT-1 transporter

Identification of Müller cells in the Nissl-stained preparations of sectioned retina proved to be difficult, since it was not possible to distinguish them unequivocally from adjacent amacrine and bipolar cells on the basis of their staining, size, shape, or location. Therefore, a retinal cell dissociation approach was used to differentiate neurons from Müller cells (Sarthy and Lam, 1979; Huba and Hofmann, 1988). Müller cells identified on the basis of their morphology and CRALBP immunoreactivity (Bunt-Milam and Saari, 1983) have a low to moderate GAT-1 RNA signal in comparison to adjacent labeled neurons. These observations are consistent with GABA uptake by Müller cells (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974), and they may explain earlier pharmacological uptake studies showing the accumulation of ACHC and DABA by Müller cells (Bauer and Ehinger, 1978; Cunningham et al., 1981), since the GAT-1 transporter is sensitive to these compounds (Guastella et 1990; Borden et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1992). Together, these in situ hybridization and pharmacological observations provide evidence that Müller cells contain GAT-1 mRNA or a highly homologous transporter.

The presence of high-affinity, ACHC- and DABA-sensitive GABA uptake systems in glia cells has been suggested by several different studies. In addition to the good evidence for such uptake systems in Müller cells of the rodent retina, cultured oligodendrocytes and astrocytes are reported to have a GABA uptake system with the properties of a neuronal GABA uptake system (Levi et al., 1983; Reynolds and Herschkowitz, 1984). In addition, ultrastructural studies using polyclonal antibodies to a purified GABA transporter preparation (Radian et al., 1986), which is likely to correspond to GAT-1 (Guastella et al., 1990), show glial membrane labeling in several regions of the nervous system (Radian et al., 1990). Together these observations indicate that high affinity, ACHC- and DABA-sensitive GABA uptake systems are not a property that is solely associated with neurons.

GABA uptake systems in the rat retina

The robust expression of GAT-1 mRNA by neurons, as well as its low to moderate level of expression by Müller cells, is in striking contrast to earlier uptake-autoradiographic pharmacological studies that show Müller cells as the predominant cell type associated with GABA uptake systems in the rat retina (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974; Brecha and Weigmann, unpublished observations). The different labeling patterns are likely to be due to several factors. For instance, there may be differences in the kinetic properties or in the translation and stability of the GAT-1 transporter when expressed by neurons or Müller cells. Furthermore, since multiple types of GABA transporter mRNAs have been recently detected in rodent nervous system (Borden et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1993), there is a possibility that Müller cells have a greater variety and greater total number of GABA plasma membrane transporters than retinal neurons. Finally, the cellular location of GABA plasma membrane transporters on retinal cells may have a strong influence on experimental observations regarding GABA uptake patterns. That is, if high-affinity GABA uptake sites are located on the apical processes and on the endfeet of Müller cells, then Müller cells would be initially labeled in either in vivo or in vitro uptake-autoradiographic experiments, since GABA must pass these cells before entering the retina when it is applied to the retinal surface.

Many of the original biochemical and pharmacological observations concerning GABA uptake systems in the rodent retina (Neal and Iversen, 1972; Starr and Voaden, 1972; Goodchild and Neal, 1973; Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Marshall and Voaden, 1974; Blanks and Roffler-Tarlov, 1982) can be parsimoniously explained by the presence of functional GAT-1 transporters on neurons and Müller cells. However, a more complete accounting of previous pharmacological observations requires additional GABA plasma membrane transporters to be expressed in the retina. For instance, the GABA agonist muscimol, which is a weak inhibitor of high-affinity GABA uptake in the CNS (Johnston, 1971), is accumulated by GABAergic retinal neurons, but apparently it is not accumulated by Müller cells (Pourcho, 1981; Blanks and Roffler-Tarlov, 1982; Hendrickson et al., 1985; Yazulla, 1986). These uptake-autoradiographic observations, therefore, suggest the existence of two transporters, one which mediates muscimol uptake into neurons and a second mediating GABA uptake into neurons and Müller cells. Other pharmacological observations also support the existence of multiple GABA transporters in the rat retina. For instance, a high-affinity, β-alanine-sensitive GABA uptake system has been demonstrated in the retina (Neal, 1976), and β-alanine is selectively accumulated by Müller cells and amacrine cells (Bruun and Ehinger, 1974). The recently described GAT-2 and GAT-3 GABA plasma membrane transporters (Borden et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1992), which are sensitive to β-alanine, could possibly be associated with some of these pharmacological observations. Indeed, molecular cloning studies indicating the presence of GAT-2 mRNA, and perhaps GAT-3 mRNA in rat retinal extracts (Borden et al., 1992), support the possibility that additional GABA plasma membrane transporters will be localized to amacrine and Müller cells.

In summary, these investigations have demonstrated the presence of a high-affinity, ACHC-sensitive GABA transporter called GAT-1 in the retina using Northern blot and in situ hybridization. This transporter mRNA is expressed by both neurons and Müller cells. The expression of a high-affinity GABA transporter by these cells is consistent with earlier general observations of GABA uptake patterns in several mammalian retinas (Bruun and Ehinger, 1974; Ehinger, 1977; Blanks and Roffler-Tarlov, 1982; Yazulla, 1986; O’Malley et al., 1992). In view of recent molecular cloning experiments (Borden et al., 1992), it is likely that other GABA transporters are localized to neurons and Müller cells and that some retinal cells express multiple GABA transporters. Finally, the present observations are consistent with earlier reports showing that GABA uptake in the inner retina is mediated by both neurons and Müller cells, and that these two cell types share some pharmacological properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. G. Casini, J. Guastella, D. W. Rickman, and C. Sternini for helpful comments on the manuscript; Dr. J. Guastella for providing the rat GAT-1 cDNA clone; and Dr. Saari for providing the cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein antibody. This work was supported by NIH grant EY 04067 and VA Medical Research Funds.

LITERATURE CITED

- Agardh E, Ehinger B. [3H]-muscimol, [3H]-nipecotic acid and [3H]-isoguvacine as autoradiographic markers for GABA neurotransmission. J. Neural Transmiss. 1982;54:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01249274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Barbour B, Szatkowski M. Nonvesicular release of neurotransmitter. Neuron. 1993;11:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90145-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Ehinger B. Retinal uptake and release of [3H]DABA. Exp. Eye Res. 1978;26:275–289. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(78)90075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beart PM, Johnston GAR, Uhr ML. Competitive inhibition of GABA uptake in rat brain slices by some GABA analogues of restricted conformation. J. Neurochem. 1972;19:1855–1861. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanks JC, Roffler-Tarlov S. Differential localization of radioactive gamma-aminobutyric acid and muscimol in isolated and in vivo mouse retina. Exp. Eye Res. 1982;35:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(82)80071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Smith KE, Hartig PR, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Molecular heterogeneity of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:21098–21104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG, Jones GP, Neal MJ. Selective inhibition of neuronal GABA uptake by cis-1,3-aminocyclohexane carboxylic acid (ACHC) Nature. 1976;264:281–284. doi: 10.1038/264281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon C. Retinal GABA neurons: Localization in vertebrate species using an antiserum to rabbit brain glutamate decarboxylase. Brain Res. 1985;344:286–295. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecha N. Retinal neurotransmitters: Histochemical and biochemical studies. In: Emson PC, editor. Chemical Neuroanatomy. Raven Press; New York: 1983. pp. 85–129. [Google Scholar]

- Brecha N, Sternini C, Anderson K, Krause JE. Expression and cellular localization of substance P/neurokinin A and neurokinin B mRNAs in the rat retina. Vis. Neurosci. 1989;3:527–535. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000986x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecha NC, Sternini C, Humphrey MF. Cellular distribution of L-glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) and γ-aminobutyric acidA (GABAA) receptor mRNAs in the retina. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1991;11:497–509. doi: 10.1007/BF00734812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecha N, Weigmann C, Messersmith E. Expression of GABA transporter mRNA in the rat central nervous system. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1992;18:473. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun A, Ehinger B. Uptake of certain possible neurotransmitters into retinal neurons of some mammals. Exp. Eye Res. 1974;19:435–447. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(74)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruun A, Ehinger B, Forsberg A. In vitro uptake of β-alanine into rabbit retinal neurons. Exp. Brain Res. 1974;19:239–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00233232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunt-Milam AH, Saari J. Immunocytochemical localization of two retinoid-binding proteins in vertebrate retina. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:703–712. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso DM, Owczarzak MT, Goebel DJ, Hazlett JC, Pourcho RG. GABA-immunoreactivity in ganglion cells of the rat retina. Brain Res. 1989;476:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casini G, Brecha NC. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-containing cells in the rabbit retina: Immunohistochemical localization and quantitative analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;305:313–327. doi: 10.1002/cne.903050212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JA, Deutch AY, Gallipoli PZ, Amara SG. Functional expression and CNS distribution of a β-alanine-sensitive neuronal GABA transporter. Neuron. 1992;9:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90172-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox KH, DeLeon DV, Angerer LM, Angerer RC. Detection of mRNAs in sea urchin by in situ hybridization using asymmetric RNA probes. Dev. Biol. 1984;101:485–502. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirgwin JM, Przybyla AE, MacDonald RJ, Rutter WJ. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J, Marshall J, Neal MJ. The radioautographical localization in the vertebrate retina of [3H]-(±)-cis-aminocyclohexane carboxylic acid (ACHC): A selective inhibitor of neuronal GABA transport. Exp. Eye Res. 1981;32:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(81)80023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RG, Eng LF. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in the retina of the developing albino rat: An immunoperoxidase study of paraffin embedded tissue. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;195:305–321. doi: 10.1002/cne.901950210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehinger B. Glial and neuronal uptake of GABA, glutamatic acid, glutamine and glutathione in the rabbit retina. Exp. Eye Res. 1977;25:221–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(77)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild M, Neal MJ. The uptake of 3H-γ-aminobutyric acid by the retina. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1973;47:529–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1973.tb08184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünert U, Wässle H. GABA-like immunoreactivity in the macaque monkey retina: A light and electron microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;297:509–524. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella J, Nelson N, Nelson H, Czyzyk L, Keynan S, Miedel MC, Davidson N, Lester HA, Kanner BI. Cloning and expression of a rat brain GABA transporter. Science. 1990;249:1303–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.1975955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson A, Ryan M, Noble B, Wu J-Y. Colocalization of [3H] muscimol and antisera to GABA and glutamic acid decarboxylase within the same neurons in monkey retina. Brain Res. 1985;348:391–396. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huba R, Hofmann H-D. Tetanus toxin binding to isolated and cultured rat retinal glial cells. Glia. 1988;1:156–164. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Solis JM, Nicoll RA. Local and diffuse synaptic actions of GABA in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1993;10:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90308-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen LL, Kelly JS. Uptake and metabolism of γ-aminobutyric acid by neurons and glial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975;24:933–938. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(75)90422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston GAR. Muscimol and the uptake of γ-aminobutyric acid by rat brain slices. Psychopharmacologia. 1971;22:230–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00401785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamermans M, Werblin F. GABA-mediated positive autofeedback loop controls horizontal cell kinetics in tiger salamander retina. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:2451–2463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02451.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner BI, Bendahan A. Two pharmacologically distinct sodium- and chloride-coupled high-affinity γ-aminobutyric acid transporters are present in plasma membrane vesicles and reconstituted preparations from rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:2550–2554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner BI, Schuldiner S. Mechanism of transport and storage of neurotransmitters. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1987;22:1–45. doi: 10.3109/10409238709082546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynan S, Suh Y-J, Kanner BI, Rudnick G. Expression of a cloned γ-aminobutyric acid transporter in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1974–1979. doi: 10.1021/bi00122a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, Wilkin GP, Ciotti MT, Johnstone S. Enrichment of differentiated, stellate astrocytes in cerebellar interneuron cultures as studied by GFAP immunofluorescence and autoradiographic uptake patterns with [3H]D-aspartate and [3H]GABA. Dev. Brain Res. 1983;10:227–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(83)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q-R, Mandiyan S, Nelson H, Nelson N. A family of genes encoding neurotransmitter transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:6639–6643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Corcuera B, Liu Q-R, Mandiyan S, Nelson H, Nelson N. Expression of a mouse brain cDNA encoding novel gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17491–17493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabjeesh NJ, Frese M, Rauen T, Jeserich G, Kanner BI. Neuronal and glial γ-aminobutyric+ acid transporters are distinct proteins. FEBS Lett. 1992;299:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80109-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J, Voaden M. An investigation of the cells incorporating [3H]GABA and [3H]glycine in the isolated retina of the rat. Exp. Eye Res. 1974;18:367–370. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(74)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosinger JL, Yazulla S, Studholme KM. GABA-like immunoreactivity in the vertebrate retina: A species comparison. Exp. Eye Res. 1986;42:631–644. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal MJ. The uptake and release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by the retina. Transport Phenomena in the Nervous System: Physiological and Pathological Aspects. In: Levi G, Battistin L, Lajtha A, editors. Plenum Press; New York: 1976. pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Neal MJ, Bowery NG. Cis-3-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid: A substrate for the neuronal GABA transport system. Brain Res. 1977;138:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal MJ, Iversen LL. Autoradiographic localization of 3H- GABA in rat retina. Nature [New Biol.] 1972;235:217–218. doi: 10.1038/newbio235217a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson H, Mandiyan S, Nelson N. Cloning of the human brain GABA transporter. FEBS Lett. 1990;269:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81149-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley DM, Sandell JH, Masland RH. Corelease of acetylcholine and GABA by the starburst amacrine cells. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1394–1408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01394.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH. Evidence for an amacrine cell system in the ganglion cell layer of the rat retina. Neuroscience. 1981;6:931–944. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrello K, Bhat SP, Bok D. Detection of interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein (IRBP) mRNA in human and cone-dominant squirrel retinas by in situ hybridization. J. Histoehem. Cytochem. 1991;39:171–176. doi: 10.1177/39.2.1987260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcho RG. Autoradiographic localization of [3H]muscimol in the cat retina. Brain Res. 1981;215:187–199. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcho RG, Owczarzak MT. Distribution of GABA immunoreactivity in the cat retina: A light and electron-microscopic study. Vis. Neurosci. 1989;2:425–435. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800012323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radian R, Bendahan A, Kanner BI. Purification and identification of the functional sodium- and chloride-coupled γ-aminobutyric acid transport glycoprotein from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15437–15441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radian R, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Castel M, Kanner BI. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABA transporter in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:1319–1330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01319.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redburn DA. Uptake and release of [14C]GABA from rabbit retina synaptosomes. Exp. Eye Res. 1977;25:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(77)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds R, Herschkowitz H. Uptake of [3H]GABA by oligodendrocytes in dissociated brain cell culture: A combined autoradiographic and immunocytochemical study. Brain Res. 1984;322:17–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthy PV, Fu M. Localization of L-glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA in cat retinal horizontal cells by in situ hybridization. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;288:593–600. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthy PV, Lam DMK. Isolated cells from a mammalian retina. Brain Res. 1979;176:208–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90889-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer J. Astrocytes in mammalian retina. In: Osborne NN, Chader GJ, editors. Progress in Retinal Research. Vol. 7. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1988. pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A. Transport and metabolism of glutamate and GABA in neurons and glial cells. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1981;22:1–45. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz EA. Depolarization without calcium can release γ-aminobutyric acid from a retinal neuron. Science. 1987;238:350–355. doi: 10.1126/science.2443977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr MS, Voaden MJ. The uptake of [14C]γ-aminobutyric acid by the isolated retina of the rat. Vision Res. 1972;12:549–557. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(72)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternini C, Anderson K, Frantz G, Krause JE, Brecha N. Expression of substance P/neurokinin A-encoding preprotachykinin messenger ribonucleic acids in the rat enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:348–356. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso JY, Sun X-H, Kao T.-h., Reece S, Wu R. Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: Genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene+ Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2485–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn JE, Famiglietti EV, Jr., Barber RP, Saito K, Roberts E, Ribak CE. GABAergic amacrine cells in rat retina: Immunocytochemical identification and synaptic connectivity. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;197:113–127. doi: 10.1002/cne.901970109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wässle H, Chun MH. GABA-like immunoreactivity in the cat retina: Light microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;279:43–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.902790105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigmann C, Brecha N. Expression of GABA neuronal transporter mRNA in the rat retina. SOC. Neurosci. Abstr. 1991;17:1565. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD, Sidhu HS. A comparative study and partial characterization of multi-uptake systems for γ-aminobutyric acid. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:1202–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb10011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi A, Uchida S, Kwon HM, Preston AS, Robey RB, Garcia-Perez A, Burg AB, Handler JS. Cloning of a Na+-and Cl− dependent betaine transporter that is regulated by hypertonicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:649–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazulla S. GABAergic mechanisms in the retina. In: Osborne NN, Chader GJ, editors. Progress in Retinal Research. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1986. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]