Abstract

Voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels (CaV1.2) are the primary Ca2+ entry pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells (myocytes). CaV1.2 channels control systemic blood pressure and organ blood flow and are pathologically altered in vascular diseases, which modifies vessel contractility. The CaV1.2 distal C-terminus is susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, which yields a truncated CaV1.2 subunit and a cleaved C-terminal fragment (CCt). Previous studies in cardiac myocytes and neurons have identified CCt as both a transcription factor and CaV1.2 channel inhibitor, with different signalling mechanisms proposed to underlie some of these effects. CCt existence and physiological functions in arterial myocytes are unclear, but important to study given the functional significance of CaV1.2 channels. Here, we show that CCt exists in myocytes of both rat and human resistance-size cerebral arteries, where it locates to both the nucleus and plasma membrane. Recombinant CCt expression in arterial myocytes inhibited CaV1.2 transcription and reduced CaV1.2 protein. CCt induced a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of both CaV1.2 current activation and inactivation, and reduced non-inactivating current in myocytes. Recombinant truncated CCt lacking a putative nuclear localization sequence (Δ92CCt) did not locate to the nucleus and had no effect on arterial CaV1.2 transcription or protein. However, Δ92CCt shifted the voltage dependence of CaV1.2 activation and inactivation similarly to CCt. CCt and Δ92CCt both inhibited pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction, although CCt was a far more effective vasodilator. These data demonstrate that endogenous CCt exists and reduces both CaV1.2 channel expression and voltage sensitivity in arterial myocytes. Thus, CCt is a bi-modal vasodilator.

Key points

Voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ (CaV1.2) channels are the major Ca2+ influx pathway and are central to contractility regulation in arterial smooth muscle cells.

CaV1.2 exists as a full-length channel and undergoes cleavage to a short CaV1.2 and a C-terminus (CCt) fragment in rat and human arterial smooth muscle cells.

CCt decreases CaV1.2 transcription and shifts the voltage dependence of current activation and inactivation to more depolarized potentials in arterial smooth muscle cells.

CCt reduces pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction.

CCt is a bi-modal vasodilator.

Introduction

Intracellular Ca2+ regulates a wide variety of cellular functions including contraction, cell proliferation, and transcription (Berridge, 1997; Jaggar et al. 2000). Voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels (CaV1.2) are the primary Ca2+ entry pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells (Gollasch & Nelson, 1997). CaV1.2 channels regulate smooth muscle cell contractility and gene expression, which controls regional organ blood flow and systemic blood pressure (Gollasch & Nelson, 1997; Cartin et al. 2000; Jaggar et al. 2000; Amberg et al. 2004). Hypertension is associated with an elevation in arterial smooth muscle cell CaV1.2 channel protein and current density, leading to vasoconstriction (Sonkusare et al. 2006; Bannister et al. 2012). Pharmacological CaV1.2 channel blockers are one therapy used to alleviate clinical hypertension. Therefore, investigating molecular signals that control CaV1.2 channel functionality in arterial smooth muscle cells provides a better understanding of mechanisms that control vascular contractility.

CaV1.2 channels are composed of pore forming α1, and auxiliary α2δ and β subunits (Catterall et al. 2005). In cardiac myocytes and neurons, the CaV1.2 intracellular C-terminus is susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, yielding a truncated (∼190 kDa, short) CaV1.2 subunit and a ∼50 kDa cleaved C-terminal fragment (CCt; De Jongh et al. 1991; Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Schroder et al. 2009). Recombinant short CaV1.2 channels generate larger whole-cell currents than do full length CaV1.2 subunits (Wei et al. 1994; Gerhardstein et al. 2000; Gao et al. 2000; Hulme et al. 2006). When expressed in tsA-201 cells, the CCt fragment re-associates with short CaV1.2 channels and shifts the voltage dependence of activation to more depolarized potentials (Hulme et al. 2006). In cardiac myocytes and neurons, the CCt fragment can also act as a transcription factor, although mechanisms described differ in these cell types (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Schroder et al. 2009). Physiological functions of CaV1.2 truncation in arterial smooth muscle cells are unclear. Similarly unclear is whether CCt fragments are present and regulate CaV1.2 functionality in smooth muscle cells and arterial contractility. Given the importance of CaV1.2 channels in the vasculature, the focus of this study was to investigate the existence and physiological functions of CCt in smooth muscle cells of resistance-size arteries.

Here, we show for the first time that CCt is present in contractile smooth muscle cells of resistance-size arteries, where it locates to both the nucleus and plasma membrane. CCt decreases smooth muscle cell CaV1.2 subunit transcription and protein and shifts the voltage dependence of current activation and inactivation to more depolarized potentials. A truncated CCt (Δ92CCt) lacking the putative nuclear localization sequence did not alter CaV1.2 protein, but shifted CaV1.2 current voltage dependence similarly to CCt. CCt and Δ92CCt both reduced pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction, with CCt being a more effective vasodilator. In summary, we demonstrate that the CCt fragment reduces both CaV1.2 channel transcription and voltage sensitivity in smooth muscle cells and therefore, acts as a bi-modal vasodilator.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal protocols used were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Tennessee Health Science Centre. Human sample was obtained with institutional review board approval, written informed consent and in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell isolation and tissue preparation

Male Sprague Dawley rats (∼250 g) were killed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg (kg body weight)−1, Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI, USA). The brain was removed and placed in chilled (4°C) physiological saline solution (PSS) containing (in mm): KCl 6, NaCl 112, NaHCO3 24, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.8, and glucose 10. Middle cerebral, posterior cerebral, and cerebellar arteries (∼100–200 μm diameter) were removed for study. Where applicable, smooth muscle cells were dissociated from cerebral arteries using enzymes, as previously described (Jaggar, 2001). A human temporal lobe brain sample was obtained from a 16-year-old male who underwent a lobectomy for the treatment of epilepsy, but had no history of hypertension or stroke. Following excision, the brain sample was placed immediately into ice-cold (4°C) DMEM. Human cerebral arteries were dissected from the sample within 1–2 h of surgery and placed in ice-cold PSS.

CCt constructs

Full-length CCt, Δ92CCt, GFP tagged CCt (CCt-GFP) and GFP tagged Δ92CCt (Δ92CCt-GFP) constructs were produced by DNA Technologies Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) CaV1.2e1b (Genbank accession number ABF85689.1) was used to generate the full-length CCt and Δ92CCt constructs. The region encompassing amino acids S1788–L2165 (377 amino acids) was inserted into pcDNA3.1 or pEGFP-N3 between BamH1 and Xho1, to generate the full-length CCt and CCt-GFP constructs, respectively. The region encompassing amino acids S1880–L2165 (285 amino acids) was inserted into pcDNA3.1 or pEGFP-N3 between BamH1 and Xho1, to generate the Δ92CCt and Δ92CCt-GFP constructs, respectively. An ATG start codon was introduced proximal to the first amino acid codon in all constructs. The predicted molecular weights are ∼41 and ∼31 kDa for full-length CCt and Δ92CCt, respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells were maintained at 37°C (21% O2–5% CO2) in DMEM (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA), supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). HEK293 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector encoding full-length CCt (DNA Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Untransfected cells were used as a control.

Cerebral arteries were transfected using reverse permeabilization as previously described (Lesh et al. 1995). Arteries were transfected with either empty vector (pcDNA3.1, control) or pcDNA3.1 encoding CCt (DNA Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) or Δ92CCt (GeneScript USA Inc., Piscatawny, NJ, USA). For confocal experiments arteries were transfected with pEGFP-N3 vectors encoding either CCt-GFP (DNA Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) or Δ92CCt-GFP (GeneScript USA Inc., Piscatawny, NJ, USA). Arteries were maintained in culture (37°C, 21% O2–5% CO2) for 4 days in DMEM (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin.

Protein analysis and biochemistry

Proteins were separated on either 12% (to visualize CCt fragments) or 7.5% (to resolve full length and truncated CaV1.2 protein) SDS–PAGE gels and analysed by Western Blotting. The 12% gels were initially probed with anti-CCt, then cut at the 75 kDa marker, stripped and re-probed for actin (below 75 kDa) and total CaV1.2 (above 75 kDa). The 7.5% gels were cut at the 75 kDa marker to allow simultaneous probing of blots for full length CaV1.2 with anti-CCt (upper portion) and actin (lower portion). Blots were then stripped and re-probed for total CaV1.2 (upper). Antibodies used were a custom anti-CCt raised to the distal CaV1.2 C-terminus (CDPGQDRAVVPEDES, Genemed Synthesis Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA), anti-CaV1.2 (Neuromab, Davis, CA, USA) and anti-actin (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative Taqman PCR reactions were carried out using an LC480 light cycler (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), as previously described (Bannister et al. 2012). Standard curves were run for all probe and primer pairs using four 10-fold dilutions of cDNA to determine PCR efficiency. CaV1.2 mRNA was calculated relative to the difference between fluorescence (Ct) values (ΔCt) for Rps5. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, with the mean used as a single experimental value. Gene specific primers and probes used were as previously described (Bannister et al. 2012).

Confocal imaging

Smooth muscle cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were blocked using 5% BSA and incubated in either wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; 1 mg ml−1), anti-CaV1.2 antibody (1:100 dilution) or anti-CCt antibody (1:100 dilution) overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed in PBS and subsequently incubated with either anti-CCt antibody or POPO-3 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) nuclear stain (15 min, 4 mm), respectively. Cells incubated with WGA or anti-CaV1.2 antibody were washed with PBS and incubated with anti-mouse Alexa 546 secondary antibodies (1 h, 37°C). Cells incubated with anti-CCt antibody were incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (1 h, 37°C) secondary antibody. The specificity of the anti-CCt and Alexa 488 antibodies was confirmed by incubating smooth muscle cells with either boiled anti-CCt first followed by Alexa 488 antibodies or Alexa 488 antibody alone (Supplemental Figure S1). Coverslips were plated onto slides using a 1:1 glycerol:PBS mounting media and edges sealed.

Images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM5 Pascal, Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) and analysed using Zeiss LSM5 Pascal Colocalization Module software. Alexa 488 and GFP were excited at 488 nm and emission collected at 505–530 nm. Alexa 546 and POPO-3 were excited at 543 nm and emission collected at ≥560 nm. Isolated myocytes were imaged through the centre of the nucleus using a z-resolution of ∼1 μm and 512 × 512 pixel density. Laser intensity and detector gain were set below saturation and were maintained constant for each experiment. The average pixel intensity of regions that did not correspond to smooth muscle cells set the background value for each image. To calculate co-localization, a region of interest was drawn around each smooth muscle cell. Overlapping pixels from different fluorophores counted as co-localized and were expressed relative to the total number of pixels above background. Weighted co-localization was then calculated using the Zeiss LSM5 Pascal Colocalization Module software.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

Smooth muscle cell voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents were recorded in isolated smooth muscle cells using the whole cell patch-clamp configuration using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, Ca, USA). Borosilicate glass electrodes (4–5 MΩ) were filled with pipette solution containing (in mm): CsMeSO4 135, CsCl 5, EGTA 5, MgATP 4, Na2GTP 0.25, Hepes 10 and glucose 10 (pH 7.2 adjusted using CsOH). Extracellular bath solution contained (in mm): NMDG 130, BaCl2 20, MgCl2 1, Hepes 10 and glucose 10 (pH 7.4 adjusted using l-aspartic acid). Cell capacitance was measured by applying a 5 mV test pulse and correcting transients with series resistance compensation.

To measure whole-cell CaV1.2 currents, 300 ms pulses to between −60 and +60 mV were applied in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of –80 mV. Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were generated from the peak current obtained during 300 ms pulses. Inactivation was measured by applying 1 s conditioning pulses to between −80 and +60 mV in 10 mV increments prior to a 200 ms test pulse to 0 mV. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz, digitized at 5 kHz, and normalized to membrane capacitance. The rate of current inactivation was calculated from current decay during each 1 s conditioning pulse. Steady-state inactivation was calculated from the current generated during each 200 ms test pulse to 0 mV. To measure steady-state activation, tail currents were elicited by repolarization to −80 mV from 20 ms test pulses from −60 to +60 mV in 10 mV increments. Whole cell currents were filtered at 1 or 5 kHz and digitized at 5 or 20 kHz for the inactivation and activation protocols, respectively. P/–4 protocols were used to subtract leak and capacitive transients. Recorded traces were filtered using a low pass Bessel filter.

Steady-state inactivation and activation curves were fitted with a single power Boltzmann function:

I/Imax=Rin+ (Rmax–Rin)/(1 + exp((V–V½)/k)),

where I/Imax is the normalized peak current, V is the conditioning pre-pulse voltage, V½ is the voltage for half-inactivation or half-activation, k is the slope factor, Rin is the proportion of non-inactivating current and Rmax is the maximal current amplitude. Current inactivation was fitted with a single exponential function:

It= (A× e(−t/τ)) +I0,

where It is the inward current at time t, A the amplitude and I0 the residual current.

Pressurized artery myography

Experiments were performed using control (empty vector) and either CCt or Δ92CCt-expressing arteries with PSS gassed with 21% O2–5% CO2–74% N2 (pH 7.4). The endothelium was removed by passing an air bubble through the lumen of the vessel for ∼1 min followed by washing with PSS. Denuded arterial segments ∼2 mm in length were cannulated at each end in a perfusion chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation, St Albans, VT, USA) that was maintained at 37°C under constant PSS perfusion. Intravascular pressure was altered using an attached reservoir and monitored using a pressure transducer. Arterial diameter was measured (1 Hz) using a CCD camera mounted on a Nikon TS100-F microscope and automatic edge detection software (Ion Wizard software; Ionoptix, Milton, MA, USA) as previously described (Adebiyi et al. 2008). Myogenic tone was calculated as: 100 × (1 –Dactive/Dpassive), where Dactive is the active arterial diameter and Dpassive the passive diameter determine by applying nimodipine (1 μm) and subsequent removal of extracellular Ca2+ by perfusing Ca2+-free PSS supplemented with 5 mm EGTA. Endothelium denudation was confirmed by an absence of a response to the endothelial-dependent vasodilator carbachol (1 μm).

Statistical analysis

Summary data are presented as means ± SEM. Significance was determined using Student's unpaired t tests with the Welsh correction, or ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keuls for multiple groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Where applicable, power analysis was performed to verify that the sample size was sufficient to give a value of >0.8.

Results

The CCt fragment is present in both rat and human cerebral artery smooth muscle cells

A custom antibody was generated to an amino acid sequence located downstream of the cleavage site in the arterial smooth muscle cell CaV1.2 channel (Cheng et al. 2007). To determine the specificity of this antibody, CCt was expressed in HEK-293 cells. The predicted molecular weight of the cleaved CCt fragment is ∼41 kDa. The anti-CCt antibody detected a band consistent with this size in lysate from HEK cells transfected with CCt (Fig. 1A). This band was not present in the same protein lysates from control untransfected HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1A). A commercial CaV1.2 antibody that recognizes an amino acid sequence located in the intracellular DII to DIII linker was used to detect CaV1.2 proteins. This commercial antibody identified 190 and 240 kDa proteins consistent with short and full-length CaV1.2 channels, but did not detect the CCt fragment, in rat and human cerebral artery lysates (Fig. 1B). The anti-CCt antibody detected bands corresponding to both full-length CaV1.2 and the CCt fragment, but did not identify short CaV1.2, in rat and human cerebral arteries (Fig. 1B and C). These data indicate that full length CaV1.2, short CaV1.2 and CCt are present in rat and human cerebral arteries.

Figure 1. An antibody raised to the distal C-terminus of CaV1.2 detects cleaved CCt and full-length CaV1.2 subunit protein in rat and human cerebral arteries.

A, representative Western blots illustrating detection of CCt fragment in lysates from HEK-293 cells overexpressing CCt. B, Western blots obtained from lysates separated on 7.5% Tris–glycine gels. Anti-CCt detected only full length CaV1.2. Anti-CaV1.2 detected both full length and truncated CaV1.2 subunit proteins. Blots are representative of 6 experiments for rat lysates. C, representative blots obtained from rat and human cerebral artery lysates separated on 12% Tris–glycine gels. Anti-CCt antibody detected full-length CaV1.2 and CCt fragment in rat and human cerebral arteries. Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-CaV1.2 antibody to illustrate location of full-length CaV1.2 subunit protein. Blots are representative of 6 experiments for rat lysates. Human cerebral artery lysate used in B and C was obtained from a 16-year-old male patient with no history of hypertension or stroke. In each panel, brightness and contrast were equally adjusted to make regions of interest in images clearer.

Endogenous CCt locates to the plasma membrane and nucleus in arterial smooth muscle cells

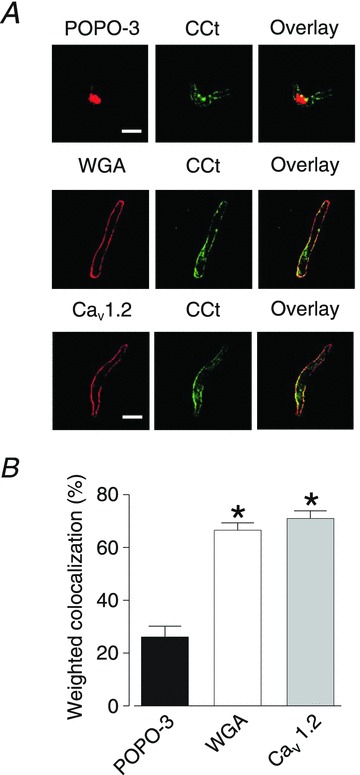

Previous studies in cardiac myocytes and neurons have indicated that the CCt fragment translocates to the nucleus and acts as a nuclear transcription factor (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Schroder et al. 2009). The intracellular distribution of the CCt fragment in arterial smooth muscle cells is unclear. To investigate endogenous CCt cellular distribution, smooth muscle cells were labelled with anti-CCt antibodies and either POPO-3, a nuclear label, or wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), a plasma membrane stain. Smooth muscle cells labelled with both boiled anti-CCt and Alexa 488 secondary antibodies or Alex 488 antibody alone did not emit fluorescence (Supplemental Figure S1). Confocal imaging indicated that the CCt antibody co-localized with POPO-3 (∼26%) and WGA (∼66%) when analysed using mean weighted pixel co-localization analysis (Fig. 2A and B). CCt has been shown to associate with short CaV1.2 channels (Hulme et al. 2006). To further investigate the plasma membrane localization of endogenous CCt, smooth muscle cells were labelled with anti-CaV1.2 antibody. CaV1.2 is present primarily (>95%) at the plasma membrane in arterial smooth muscle cells (Bannister et al. 2009, 2011, 2012). Anti-CCt and anti-CaV1.2 antibodies co-localized well (∼70%), but not fully, suggesting that short CaV1.2 channels also locate to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2. Endogenous CCt locates to the nucleus and plasma membrane in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells.

A, representative confocal images illustrating co-localization of endogenous CCt with the nucleus (POPO-3), plasma membrane (WGA) and a commercial CaV1.2 antibody in isolated arterial smooth muscle cells. Scale bars represent 10 μm. B, mean data illustrating weighted co-localization between endogenous CCt, nucleus, WGA or commercial CaV1.2 antibody. *Significant difference from nuclear co-localization (P < 0.05, n= 6–7).

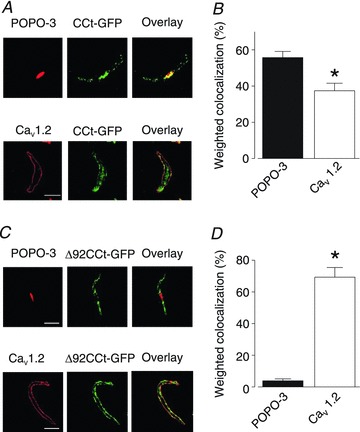

The anti-CCt antibody recognizes both full-length CaV1.2 and CCt. To further investigate CCt cellular distribution, GFP-tagged CCt (CCt-GFP) was expressed in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. CCt-GFP fluorescence co-localized with POPO-3 (∼55%), indicating nuclear localization (Fig. 3A and B). CCt-GFP also co-localized with CaV1.2 (∼37%, Fig. 3A and B), further suggesting localization with CaV1.2 channels. A GFP-tagged truncated CCt fragment lacking the nuclear translocation sequence (Δ92CCt-GFP) did not locate to the nucleus, but co-localized with CaV1.2 (∼69%, Fig. 3C and D) in arterial smooth muscle cells. These data indicate that the CCt fragment locates to both the nucleus and plasma membrane in arterial smooth muscle cells. These data also suggest that CCt can re-associate with, or nearby, short plasma membrane CaV1.2 channels.

Figure 3. CCt-GFP distributes to the nucleus and plasma membrane in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells.

A, representative confocal images illustrating co-localization of GFP-tagged CCt (CCt-GFP) with the nucleus (POPO-3) and a commercial CaV1.2 antibody in isolated arterial smooth muscle cells. B, mean data showing weighted co-localization between CCt-GFP and nucleus (POPO-3) or CaV1.2. C, confocal images illustrating co-localization of GFP-tagged Δ92CCt (Δ92CCt-GFP) with the nucleus or CaV1.2. D, mean data illustrating weighted co-localization between Δ92CCt-GFP and nucleus or CaV1.2. *Significant difference from nuclear co-localization (P < 0.05, n= 6–9). Scale bars represent 10 μm.

CCt acts as a nuclear-targeting CaV1.2 transcriptional regulator

Transcriptional regulation by the CCt fragment was investigated in arterial smooth muscle cells. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on arteries transfected with vectors encoding CCt or Δ92CCt, using empty vector as a control. CCt expression decreased CaV1.2 mRNA to ∼75% of that in control arteries (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Δ92CCt expression did not alter CaV1.2 mRNA (∼102% of control, Fig. 4A). Rps5 mRNA, the reporter gene used in this assay, was unchanged by expression of either full-length CCt or Δ92CCt (99 ± 3% of control for CCt and 96 ± 1% of control for Δ92CCt).

Figure 4. CCt inhibits CaV1.2 expression in cerebral arteries.

A, bar graph illustrating mean CaV1.2 mRNA transcript levels in cerebral expressing either CCt or Δ92CCt when compared to control. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05, n= 5). B, representative Western blots illustrating expression of CCt and Δ92CCt and subsequent changes in CaV1.2 protein in arteries. Blots were cut at the 75 kDa marker. The lower blot was probed for actin and CCt. The upper blot was probed for CCt then stripped and re-probed for CaV1.2 protein. Brightness and contrast were equally adjusted in all panels to make regions of interest in images clearer. C, mean data showing percentage change in total protein for CCt (endogenous, eCCt and recombinant full-length, rCCt) and CaV1.2 in rCCt-expressing cerebral arteries compared to control. D, mean data showing percentage change in total protein for CCt (eCCt and Δ92CCt) and CaV1.2 in Δ92CCt-expressing cerebral arteries compared to control. *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05, n= 4–7).

Western blotting indicated that CCt or Δ92CCt expression similarly increased levels of total CCt protein in arteries (Fig. 4B–D). CCt expression increased total CCt (endogenous + recombinant CCt) to ∼147% of control (endogenous CCt alone, Fig. 4B and C). Δ92CCt expression similarly increased total CCt protein (endogenous + recombinant Δ92CCt) to ∼147% of control (Fig. 4B and D). Probing blots using the anti-CCt antibody demonstrated that CCt expression reduced full-length (240 kDa) CaV1.2 protein to ∼66% of control (Fig. 4B and C). Western blotting using the commercial anti-CaV1.2 antibody indicated that CCt expression reduced total CaV1.2 (240 kDa and 190 kDa) protein to ∼59% of control (Fig. 4B and C). In contrast, Δ92CCt did not alter full-length (∼96% of control) or total (∼95% of control) CaV1.2 protein (Fig. 4A–D). CCt or Δ92CCt expression also did not alter the ratio of full-length to short CaV1.2 protein (1.8 ± 0.3 and 1.6 ± 0.1, respectively), compared to control (1.7 ± 0.3). Taken together, these data indicate that nuclear localization of the CCt fragment inhibits CaV1.2 gene expression.

CCt reduces CaV1.2 current density and shifts voltage dependence in arterial smooth muscle cells

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from arteries expressing CCt or Δ92CCt and used for electrophysiology. Ba2+ (20 mm) was used as the charge carrier to record CaV1.2 currents. CCt expression reduced CaV1.2 current density from ∼2.2 pA pF−1 in control to 1.3 pA pF−1, or by ∼42%. CCt also shifted CaV1.2 current peak voltage from ∼16.8 to 20.6 mV, or by ∼4.8 mV (Fig. 5A and B and Table 1). CCt shifted the voltage of half-maximal activation (V½act) from ∼+4.7 to +13.6 mV, or by ∼8.9 mV (Fig. 5C and Table 1). The voltage of half-maximal inactivation (V½inact) was also shifted from ∼−22.3 to −11.5 mV, or by ∼10.8 mV (Fig. 5D and Table 1). Non-inactivating CaV1.2 current decreased from ∼12% of total current in control to 3% in CCt-expressing cells (Fig. 5D). CCt expression did not significantly alter the slope of either the steady-state activation or inactivation curves. CCt expression also slowed the rate of current inactivation ∼1.9-fold when compared with control (Fig. 5E). Figure 5F illustrates effects of CCt expression on arterial smooth muscle cell CaV1.2 window currents.

Figure 5. CCt reduces CaV1.2 current density and shifts voltage dependence.

A, representative CaV1.2 current recordings from control smooth muscle cells and cells expressing CCt or Δ92CCt. For clarity, only steps to −60, −20, 0, +20 and +60 mV are shown. B, mean I–V relationships of control cells (n= 10) and CCt- (n= 12) and Δ92CCt-expressing (n= 8) arterial smooth muscle cells. C, voltage-dependent current activation for CaV1.2 currents obtained from control cells (n= 10) and CCt- (n= 7) and Δ92CCt-expressing (n= 5) cells. D, voltage-dependent current inactivation for CaV1.2 currents from control cells (n= 14) and CCt- (n= 8), and Δ92CCt-expressing (n= 8) cells. E, kinetics of inactivation for control cells (n= 14) and CCt- (n= 8), and Δ92CCt-expressing (n= 8) cells. F, plots showing the area under the steady-state activation and inactivation curves (window current) for control cells and CCt- and Δ92CCt-expressing cells. *Significant difference between control and CCt (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between control and Δ92CCt (P < 0.05). §Significant difference between CCt and Δ92CCt (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Properties of CaV1.2 currents from isolated control cells or cells expressing CCt- or Δ92CCt

| Control | CCt | Δ92CCt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I–V relationship | |||

| Peak current density (pA pF−1) | 2.2 ± 0.2 (10) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (12)* | 2.1 ± 0.3 (10)# |

| Peak voltage (mV) | 16.8 ± 0.9 (10) | 20.6 ± 0.9 (12)* | 15.5 ± 1.7 (10)# |

| Voltage-dependent activation | |||

| V½act (mV) | 4.7 ± 0.8 (10) | 13.6 ± 3.6 (7)* | 10.3 ± 2.5 (5)* |

| Slope | 17.2 ± 1.7 (10) | 18.1 ± 2.7 (7) | 15.0 ± 2.3 (5)* |

| Voltage-dependent inactivation | |||

| V½inact (mV) | −22.3 ± 1.1 (14) | −11.5 ± 1.4 (8)* | −15.1 ± 1.8 (8)* |

| Slope | 11.0 ± 1.0 (14) | 12.8 ± 1.3 (8) | 13.1 ± 1.5 (8) |

Numbers in parenthesis indicate experimental number. *P < 0.05 when compared to control; #P < 0.05 when compared to CCt.

The CCt fragment can re-associate with short CaV1.2 subunits via a proline rich domain (Gerhardstein et al. 2000), which is present in the Δ92CCt construct used here. Δ92CCt expression did not alter CaV1.2 current density (2.3 ± 0.3 pA pF−1), but shifted peak voltage, the V½act and the V½inact (∼5.3 and ∼7.2 mV, respectively) similarly to CCt (Fig. 5A and B and Table 1). Δ92CCt also shifted the voltage dependence of the window current and slowed inactivation kinetics ∼1.7-fold (Fig. 5C–F). These data suggest that CCt reduces CaV1.2 current in arterial smooth muscle cells through two different mechanisms: transcriptional inhibition of CaV1.2 channels reduces CaV1.2 current density, and re-association with short CaV1.2 channels right shifts voltage-dependent activation.

CCt dilates cerebral arteries

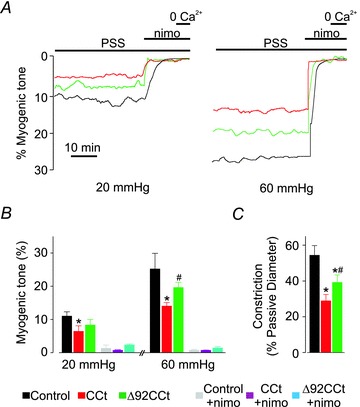

To examine the functional significance of CCt in arterial smooth muscle cells, pressure-induced vasoconstriction (myogenic tone) was measured in small (∼250 μm diameter) cerebral arteries in which recombinant CCt or Δ92CCt were expressed. An elevation in intravascular pressure to 20 or 60 mmHg in control (empty vector) arteries stimulated the development of ∼11% and 25% myogenic tone, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). Membrane depolarization (60 mm K+, 60 mmHg) constricted control arteries to ∼54% of passive diameter (Fig. 6C). CCt expression reduced myogenic tone by ∼42 and 45% at 20 and 60 mmHg, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). CCt also reduced depolarization-induced vasoconstriction by ∼47% (Fig. 6C). Δ92CCt reduced myogenic tone at 20 and 60 mmHg by ∼25 and 23%, respectively and 60 mm K+-induced tone by ∼38% (Fig. 6A–C). Thus, Δ92CCt expression reduced pressure- and depolarization-induced constriction less effectively than CCt. Collectively, these data indicate that CCt dilates cerebral arteries both by reducing CaV1.2 current density through a transcriptional mechanism and by directly inhibiting CaV1.2 channels.

Figure 6. CCt expression reduces pressure- and depolarization induced vasoconstriction in cerebral arteries.

A, representative diameter traces illustrating steady-state myogenic tone at 20 and 60 mmHg for control arteries and arteries expressing either CCt or Δ92CCt. B, mean data illustrating pressure-induced tone at 20 and 60 mmHg for control and CCt- and Δ92CCt-expressing arteries. C, bar graph indicating mean depolarization-induced constriction induced by elevating extracellular K+ from 6 to 60 mm in control and arteries expressing either CCt or Δ92CCt. *Significant difference between control and CCt (P < 0.05). #Significant difference between CCt and Δ92CCt (P < 0.05).

Discussion

CaV1.2 channels are the major Ca2+ entry pathway in arterial smooth muscle cells. The existence and physiological functions of the CCt fragment have not been demonstrated in vascular smooth muscle. This study shows for the first time that the CCt fragment is present in smooth muscle cells of small resistance-size arteries. CCt can translocate to the nucleus, leading to a reduction in CaV1.2 transcription, protein and currents in arterial smooth muscle cells. Data here show that CCt shifts current V½act, V½inact, and rate of inactivation, an effect that may be due to re-association with plasma membrane short CaV1.2 channels. Deletion of the CCt nuclear localization signal abolishes transcriptional inhibition of CaV1.2, but does not alter modulation of CaV1.2 current biophysical properties. These data indicate that CCt inhibits CaV1.2 channel transcription and directly reduces voltage-dependent current activation to inhibit myogenic tone in pressurized arteries. In summary, data show that the CCt fragment is both a bi-modal CaV1.2 channel inhibitor and vasodilator.

Full length CaV1.2 subunits are susceptible to post-translational modification by proteolytic processing of their C-terminus to yield a truncated CaV1.2 channel and a CCt fragment (De Jongh et al. 1996). Neuronal and skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channels are cleaved by calpain, a calcium-dependent cysteine protease (De Jongh et al. 1994; Hell et al. 1996). Recombinant cardiac CaV1.2 channels expressed in Sf9 cells are cleaved by chymotrypsin (Gerhardstein et al. 2000). In contrast, recombinant CaV1.2 subunits expressed in Sf9 or HEK cells do not undergo proteolytic cleavage (Chien et al. 1995; Puri et al. 1997). We and others have previously reported that CaV1.2 subunits exist as both full length (∼240 kDa) and short (∼190 kDa) forms in arterial smooth muscle cells (Sonkusare et al. 2006; Cheng et al. 2007; Xue et al. 2007; Bannister et al. 2009, 2011). Future studies should aim to determine enzymes responsible for CaV1.2 cleavage in arterial smooth muscle cells and investigate if this process is regulated physiologically. Such knowledge may demonstrate that control of CaV1.2 cleavage and CCt production are functional mechanisms to modulate CaV1.2 currents and vascular contractility. One approach that could have been applied in this study would have been to manipulate endogenous levels of CCt. However, given that mechanisms modulating CCt cleavage are currently unidentified, we overexpressed CCt to study its physiological functions in smooth muscle cells of small resistance-size cerebral arteries.

We previously cloned CaV1.2 channels (CaV1.2e1b and CaV1.2e1c) expressed in resistance-size cerebral arteries (Cheng et al. 2007), the preparation studied here. The amino acid sequences located downstream of the identified cleavage site in CaV1.2 are identical in CaV1.2e1b and CaV1.2e1c. The predicted molecular weight of both the endogenous and recombinant CCt is ∼41 kDa. Our custom anti-CCt antibody detected a similar size band just below the 50 kDa marker in Fig. 1C (endogenous) and A (overexpressed in HEK cells) and Fig. 3B (overexpressed in cerebral arteries). In contrast, Schroder et al. (2009) detected a band for CCt at ∼37 kDa. It is unknown whether post-translational modification of CCt occurs, or differs in HEK-293, tsA-201 cells, adult ventricular myocytes and arterial smooth muscle cells. Such modifications may explain differences in these apparent molecular weights.

CCt can localize to both the nucleus and plasma membrane in cardiac myocytes and neurons (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Schroder et al. 2009). Here, we show that both endogenous and recombinant CCt locate to the nucleus and plasma membrane in arterial smooth muscle cells. Given that CCt does not contain transmembrane domains and that CCt-GFP co-localizes with surface CaV1.2 channels, these data suggest functional interaction. Deletion of a putative conserved nuclear localization sequence within CCt abolished nuclear localization in arterial smooth muscle cells. This result is similar to that described for recombinant CCt expressed in HEK 293T cells (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006). In contrast, deletion of the putative nuclear localization sequence increased nuclear CCt in murine cardiac myocytes (Schroder et al. 2009). These data suggest that mechanisms targeting CCt to the nucleus vary in different cell types, but that the previously described nuclear localization sequence is essential for this mechanism in arterial smooth muscle cells. CCt can re-associate with short CaV1.2 channels via a proline rich domain or via electrostatic interactions between negatively charged glutamate (2103, 2106) and aspartate (2110) residues within CCt and positively charged arginine residues (1696–1697) within the CaV1.2 C-terminus (Gerhardstein et al. 2000; Hulme et al. 2006). Here, we used Δ92CCt-GFP, which contains residues necessary for CaV1.2 re-association, but lacks the proximal 92 amino acids containing the conserved nuclear localization sequence. Δ92CCt-GFP co-localized with plasma membrane CaV1.2 channels, but was not observed in the nucleus in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Imaging data suggest CCt locates to other intracellular localizations that may include endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi and trafficking vesicles. Labelling using the CCt antibody cannot differentiate between the endogenous CCt fragment or full-length CaV1.2 protein. Therefore, it is not clear if one or both of these proteins locate to other intracellular organelles. In summary, our data suggest that the nuclear localization sequence is essential for CCt nuclear translocation and that CCt re-associates with short CaV1.2 channels in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells.

CaV1.2 channel expression is controlled by distinct promoters (Dai et al. 2002; Saada et al. 2005; Bannister et al. 2011). Arterial myocyte CaV1.2 channels primarily contain exon 1c-encoded N-termini (CaV1.2e1c), whereas cardiac myocyte CaV1.2 channels contain N-termini encoded by exon-1b (Blumenstein et al. 2002; Liao et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2007; Bannister et al. 2011). In rat cardiac myocytes, both full-length and truncated CCt reduced CaV1.2 promoter activity, with truncated CCt inhibiting more than full-length CCt, suggesting increased promoter binding (Schroder et al. 2009). In contrast, CCt expression upregulated 66 mRNAs and repressed ∼206 genes in Neuro2A cells in a study in which CaV1.2 was not identified as a gene altered by CCt (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006). Mice (DCT−/−) that express CaV1.2 channels with a truncation at G1796, which is located in the distal C-terminus, died from congestive heart failure as early as embryonic day 15 (Fu et al. 2011). In these mice, cardiac myocyte CaV1.2 mRNA was similar, whereas CaV1.2 protein and currents were reduced (Fu et al. 2011). Here, CCt expression reduced CaV1.2 mRNA, CaV1.2 protein and CaV1.2 currents in arterial smooth muscle cells. Explanations for this disparity in results are that CCt deletion in cardiac myocytes of DCT−/− mice stimulates CaV1.2 degradation, or that CCt expression reduces CaV1.2 mRNA stability. Promoters that control CaV1.2 expression in arterial smooth muscle cells are poorly understood, with the promoter for CaV1.2e1c not reported. Therefore investigating the mechanism of direct regulation of CaV1.2 promoter activity by CCt in small cerebral arteries is beyond the scope of this project. Taken together, our data suggest that CCt reduces CaV1.2 transcription, leading to a reduction in protein and current density in arterial smooth muscle cells.

CCt fragment expression reduced peak CaV1.2 current density and caused a positive shift in CaV1.2 current V½act that would reduce functional voltage-dependent activation in arterial smooth muscle cells. When combined with imaging data in this study and previous data (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Hulme et al. 2006; Fuller et al. 2010), results suggest that CCt re-associates with short CaV1.2 channels to alter voltage dependence. Consistent with this conclusion, CaV1.2 currents in cardiac myocytes of DCT−/− mice display a hyperpolarizing shift in V½act and increased whole cells currents (Fu et al. 2011). CCt expression (residues 1821–2171) reduced recombinant CaV1.2Δ1821 current amplitude and shifted the V½act to more depolarized potentials in tsA-201 cells (Hulme et al. 2006). In a similar study DCT expression reduced recombinant CaV1.2Δ1800 current amplitude in a dose-dependent manner in tsA-201 cells (Fuller et al. 2010). CCt expression also positively shifted the V½inact and slowed current inactivation in arterial smooth muscle cells. In contrast, deletion of the distal C-terminus did not alter the V½inact of CaV1.2 channels or current inactivation in cardiac myocytes of DCT−/− mice (Hulme et al. 2006; Fu et al. 2011). One explanation for these differences is that mechanisms by which CCt regulates cardiac and smooth muscle cell CaV1.2 channels may differ. The C-terminus of CaV1 channels is encoded by multiple exons, with alternative splicing between exons 40 and 43 occurring in cardiac myocytes (Klockner et al. 1997; Soldatov et al. 1997; Safa et al. 2001; Jurkat-Rott & Lehmann-Horn, 2004). The CaV1.2 channel C-terminus does not undergo alternate splicing in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells (Cheng et al. 2009). Deletion of a proline rich domain within CCt impaired membrane association (Gerhardstein et al. 2000). Here, Δ92CCt, in which the nuclear localization sequence is omitted but the proline rich region is retained (Gerhardstein et al. 2000), did not alter CaV1.2 protein or peak CaV1.2 current density, but shifted V½act and V½inact similarly to full-length CCt. A recent study demonstrated that Ca2+–calmodulin attenuates CaV1.2 current inhibition by CCt in HEK293 cells and cardiomyocytes (Crump et al. 2013). Here, Ba2+ was the charge carrier in patch-clamp experiments. We show in functional experiments that CCt attenuates arterial contractility when Ca2+ is the permeant ion. Therefore, these data support the conclusion that CCt inhibits CaV1.2 when Ca2+ is permeant. Future studies should aim to investigate whether Ca2+ modifies CCt-regulation of CaV1.2 currents in arterial myocytes, as is observed in cardiac myocytes (Crump et al. 2013). In summary, our data suggest that the CCt fragment can re-associate with short CaV1.2 subunits, leading to modulation of voltage dependence that reduces channel activity at steady-state physiological potentials in arterial smooth muscle cells.

Elevating intravascular pressure induces steady-state depolarization of smooth muscle cells within resistance-size cerebral arteries to between −60 and −30 mV, with a voltage of ∼−40 mV at a physiological pressure of ∼60 mmHg (Knot & Nelson, 1998). Although CCt and Δ92CCt expression both inhibited pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction, CCt dilated more so than did Δ92CCt. These data are consistent with CCt decreasing both CaV1.2 current density and voltage sensitivity, whereas Δ92CCt reduces only CaV1.2 channel voltage sensitivity. The depolarizing shift in V½inact and slower inactivation kinetics caused by both CCt and Δ92CCt overexpression would be expected to prolong CaV1.2 channel opening and thereby increase Ca2+ influx and pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction. However, the CaV1.2 window current, a measure of current over a steady-state voltage range, was right shifted. Thus, voltage-dependent activation, which is necessary to induce CaV1.2-dependent Ca2+ influx, is a major factor critical for CCt functionality. These data suggest that CCt attenuates both pressure- and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction by reducing CaV1.2 current density and by shifting the V½act to more depolarized potentials.

In summary, we demonstrate that the CCt fragment dilates resistance-size cerebral arteries by decreasing CaV1.2 transcription, protein, and CaV1.2 channel voltage-sensitivity in smooth muscle cells. These data are consistent with CCt acting as a bi-modal vasodilator.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Simon Bulley for critical reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DCT−/−

distal C-terminus knockout

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- NMDG

N-methyl-d-glucamine

- Nimo

nimodipine

- POPO-3

benzoxazolium, 2,2′- [1,3-propanediylbis[(dimethyliminio)-3, 1-propanediyl-1(4H)-pyridinyl-4-ylidene-1-propen-1-yl-3-ylidene]]bis[3-methyl]-, tetraiodide

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

Additional information

Competing interests

None.

Author contributions

All experiments were performed in the laboratory of Professor Jonathan H. Jaggar in the Department of Physiology at UT-Health Science Centre, Memphis, TN, USA. The authors contributed to the study as follows: J.P.B. contributed significantly to the conception and design of experiments, collection, analysis and interpretation of data and to the drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. M.D.L. contributed significantly to the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and to the drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. D.N., W.J., A.N., K.W.E., J.P., K.S.G. and F.A.B. contributed significantly to the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. J.H.J. contributed significantly to the conception and design of experiments and to the drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to J.H.J from NIH/NHLBI.

Supplementary material

Figure S1

References

- Adebiyi A, McNally EM, Jaggar JH. Sulfonylurea receptor-dependent and -independent pathways mediate vasodilation induced by KATP channel openers. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:736–743. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg GC, Rossow CF, Navedo MF, Santana LF. NFATc3 regulates Kv2.1 expression in arterial smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47326–47334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas CM, Feng JY, Jaggar JH. Smooth muscle cell α2δ-1 subunits are essential for vasoregulation by CaV1.2 channels. Circ Res. 2009;105:948–955. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Bulley S, Narayanan D, Thomas-Gatewood C, Luzny P, Pachuau J, Jaggar JH. Transcriptional upregulation of α2δ-1 elevates arterial smooth muscle cell voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel surface expression and cerebrovascular constriction in genetic hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:1006–1015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Thomas-Gatewood CM, Neeb ZP, Adebiyi A, Cheng X, Jaggar JH. CaV1.2 channel -terminal splice variants modulate functional surface expression in resistance size N artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15058–15066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. J Physiol. 1997;499:290–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstein Y, Kanevsky N, Sahar G, Barzilai R, Ivanina T, Dascal N. A novel long N-terminal isoform of human L-type Ca2+ channel is up-regulated by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3419–3423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartin L, Lounsbury KM, Nelson MT. Coupling of Ca2+ to CREB activation and gene expression in intact cerebral arteries from mouse : roles of ryanodine receptors and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Circ Res. 2000;86:760–767. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Liu J, Asuncion-Chin M, Blaskova E, Bannister JP, Dopico AM, Jaggar JH. A novel CaV1.2 N terminus expressed in smooth muscle cells of resistance size arteries modifies channel regulation by auxiliary subunits. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29211–29221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610623200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Pachuau J, Blaskova E, Asuncion-Chin M, Liu J, Dopico AM, Jaggar JH. Alternative splicing of Cav1.2 channel exons in smooth muscle cells of resistance-size arteries generates currents with unique electrophysiological properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H680–H688. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00109.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien AJ, Zhao X, Shirokov RE, Puri TS, Chang CF, Sun D, Rios E, Hosey MM. Roles of a membrane-localized β subunit in the formation and targeting of functional L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30036–30044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.30036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump SM, Andres DA, Sievert G, Satin J. The cardiac L-type calcium channel distal carboxy terminus autoinhibition is regulated by calcium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H455–H464. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00396.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B, Saada N, Echetebu C, Dettbarn C, Palade P. A new promoter for α1C subunit of human L-type cardiac calcium channel CaV1.2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00894-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh KS, Colvin AA, Wang KK, Catterall WA. Differential proteolysis of the full-length form of the L-type calcium channel α1 subunit by calpain. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1558–1564. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63041558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh KS, Murphy BJ, Colvin AA, Hell JW, Takahashi M, Catterall WA. Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full-length form of the α1 subunit of the cardiac L-type calcium channel by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10392–10402. doi: 10.1021/bi953023c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh KS, Warner C, Colvin AA, Catterall WA. Characterization of the two size forms of the α1 subunit of skeletal muscle L-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10778–10782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Yu FH, Clark JP, III, Marshall MR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Deletion of the distal C-terminus of CaV1.2 channel leads to loss of β-adrenergic regulation and heart failure in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12617–12626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight-or-flight response. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Ma H, Hosey MM. Role of the C terminus of the α1C (CaV1.2) subunit in membrane targeting of cardiac L-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25436–25444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Bunemann M, Puri TS, Adair A, Ma H, Hosey MM. Proteolytic processing of the C terminus of the α1C subunit of L-type calcium channels and the role of a proline-rich domain in membrane tethering of proteolytic fragments. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8556–8563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollasch M, Nelson MT. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in arterial smooth muscle cells. Kidney Blood Press Res. 1997;20:355–371. doi: 10.1159/000174250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ospina N, Tsuruta F, Barreto-Chang O, Hu L, Dolmetsch R. The C terminus of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.2 encodes a transcription factor. Cell. 2006;127:591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell JW, Westenbroek RE, Breeze LJ, Wang KK, Chavkin C, Catterall WA. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-induced proteolytic conversion of postsynaptic class C L-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3362–3367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Lin TW, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Autoinhibitory control of the CaV1.2 channel by its proteolytically processed distal C-terminal domain. J Physiol. 2006;576:87–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH. Intravascular pressure regulates local and global Ca2+ signaling in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C439–C448. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C235–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkat-Rott K, Lehmann-Horn F. The impact of splice isoforms on voltage-gated calcium channel α1 subunits. J Physiol. 2004;554:609–619. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockner U, Mikala G, Eisfeld J, Iles DE, Strobeck M, Mershon JL, Schwartz A, Varadi G. Properties of three COOH-terminal splice variants of a human cardiac L-type Ca2+-channel α1-subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;272:H1372–H1381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.3.H1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol. 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesh RE, Somlyo AP, Owens GK, Somlyo AV. Reversible permeabilization. A novel technique for the intracellular introduction of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides into intact smooth muscle. Circ Res. 1995;77:220–230. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P, Yong TF, Liang MC, Yue DT, Soong TW. Splicing for alternative structures of Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in cardiac and smooth muscles. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri TS, Gerhardstein BL, Zhao XL, Ladner MB, Hosey MM. Differential effects of subunit interactions on protein kinase A- and C-mediated phosphorylation of L-type calcium channels. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9605–9615. doi: 10.1021/bi970500d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada NI, Carrillo ED, Dai B, Wang WZ, Dettbarn C, Sanchez J, Palade P. Expression of multiple CaV1.2 transcripts in rat tissues mediated by different promoters. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safa P, Boulter J, Hales TG. Functional properties of CaV1.3 (α1D) L-type Ca2+ channel splice variants expressed by rat brain and neuroendocrine GH3 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38727–38737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder E, Byse M, Satin J. L-type calcium channel C terminus autoregulates transcription. Circ Res. 2009;104:1373–1381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov NM, Zuhlke RD, Bouron A, Reuter H. Molecular structures involved in L-type calcium channel inactivation. Role of the carboxyl-terminal region encoded by exons 40–42 in α1C subunit in the kinetics and Ca2+ dependence of inactivation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3560–3566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkusare S, Palade PT, Marsh JD, Telemaque S, Pesic A, Rusch NJ. Vascular calcium channels and high blood pressure: pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Neely A, Lacerda AE, Olcese R, Stefani E, Perez-Reyes E, Birnbaumer L. Modification of Ca2+ channel activity by deletions at the carboxyl terminus of the cardiac α1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1635–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue JH, Zhang LF, Ma J, Xie MJ. Differential regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in cerebral and mesenteric arteries after simulated microgravity in rats and its intervention by standing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H691–H701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01229.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.