Abstract

Rapid separation, characterization and quantitation of curcuminoids are important owing to their numerous pharmacological properties including antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities. In the present study, pseudo two dimensional liquid flash chromatography was used for the separation of four curcuminoids (curcumin, demethoxy curcumin, bisdemethoxy curcumin and dihydro bisdemethoxy curcumin) for the first time. Silica and diol columns were used for separation of curcuminoids using gradient mobile phase. The separated peaks were monitored at 244, 360 nm to obtain four compounds. The purity of compounds were determined by rapid quantitative 1H NMR (qNMR) using 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionic-(2,2,3,3-d4) acid sodium salt (TSP-d4) (0.012%) in D2O. These results were compared with those obtained by HPLC method. The purity of isolated curcuminoids using pseudo 2D chromatography was found to be in the range of 92.4–95.45%. The structures of these compounds were characterized unambiguously using 13C (APT) NMR spectra. The developed pseudo 2D separation technique has the advantage of simplified automation with shorter run time compared to conventional separation techniques. The method that combines rapid pseudo 2D separation and simple quantitation using qNMR reported herein can be of wide utility for routine analysis of curcuminoids in complex mixtures.

Keywords: Curcuma longa, turmeric, two-dimensional separation; preparative chromatography, qNMR, LC-MS

Introduction

Turmeric, Curcuma longa L., is a well-known spice of the Zingiberacea family and a natural colorant [1]. Traditional Indian medicine claims the use of Curcuma longa against numerous diseases including biliary disorders, anorexia, coryza, cough, diabetic wounds, hepatic disorder, rheumatism and sinusitis [2, 3]. Curcumin [1,7–bis-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione] is regarded as the most biologically active constituent [4]. Turmeric also consists of other minor compounds, apart from the major curcumin [1]. Commercial curcumin is a mixture of curcuminoids containing approximately 77% curcumin, 18% demethoxy curcumin (DMC) and 5% bisdemethoxy curcumin (BDMC) [4]. Several studies have shown that commercial curcumin has cytotoxic effects on different types of cancer cells [5–7]; however, these effects are due to synergistic and/or additive effects of major and minor curcuminoids and the mechanisms of such effects are not fully understood. Owing to their potential biological effects on cancer cells, the demand for demethoxy curcumin (DMC) and bisdemethoxy curcumin (BDMC) has tremendously increased recently [8, 9]. To study such effects, researchers need large quantities of individual curcuminoids to test in vivo and clinical studies. Thus it is imperative to develop rapid methods for the separation of individual curcuminoids for the mechanistic studies.

A number of separation techniques have been reported for isolation and purification of curcuminoids from turmeric [4, 10–12]. Among these, separation by open column is the most common method for purification of curcuminoids for preparative scale. High-speed countercurrent chromatography has been reported for separation of milligram quantities of curcuminoids from turmeric extract using a multiple solvent system [13]. Patel and Krishna have reported a pH zone refining method for purification of curcuminoids exploiting the their weakly acidic nature [14]. We have reported a method for the isolation of mixture of curcuminoids from crude extracts by selective solvent extraction method to use as food additives [15]. In addition, we also reported separation of individual curcuminoids using conventional open column chromatographic technique to separate pure compounds [4]. The open column techniques are tedious, require large quantity of solvents and not reproducible [16–18]. To overcome such challenges, hyphenated techniques were developed for the rapid separation and partial identification of natural products [19]. However, isolation of pure curcuminoids (mg to gram quantities) using these techniques is time consuming and tedious. Separation of complex mixtures using preparative HPLC, in grams level in single run is challenging. To alleviate such problems, two-dimensional gradient elution is attempted using binary normal phase solvent systems.

Often, hyphenated techniques involve a combination of two or more analytical techniques (usually a separation and a spectroscopic technique) into one integrated technique [20]. In this direction, HPLC coupled with UV spectroscopy (LC-UV), GC-MS and LC-MS were emerged as advanced hyphenated techniques [4, 21–23]. Traditionally, UV-Visible absorption measurements were used for quantification of total curcuminoids [24]. These methods provide total color content of turmeric, and concentrations of individual curcuminoids cannot be determined directly from turmeric samples. Analytical HPLC techniques provide purity of each compound [4, 21–23, 25]; these methods need authentic standards for calibration, sample preparation step will be time consuming and each sample run time will be 10–60 min.

The term “pseudo-multidimensional” was used for sequential separation in a column where part of the sample is stored (adsorbed) at the 1st column in the first step (“pseudo-first” dimension) while the other part is separated into its individual components in 2nd column. In the following step (second dimension), the chromatographic conditions are changed and the stored part of the sample is separated [26]. In other words, pseudo-multidimensional involves multistep separation of components with more than one separative mode [26–28]. Curcuminoids are structurally similar compounds and obtaining satisfactory recovery is always challenging due to very close retardation factor. Thus, we have successfully developed a pseudo two-dimensional separation method to isolate curcumin, demethoxy curcumin, bisdemethoxy curcumin and dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin at the preparative level in one run. This hyphenated technique is highly efficient, rapid and simple to perform. The rapid separation is combined with quantitative method (qNMR) to determine purity of the separated curcuminoids, for the first time.

1. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

The turmeric oleoresin was obtained from Sami Labs Limited (Bangalore, India) and stored at 4°C. Solvents used for the analysis were all HPLC-grade and were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Nanopure water (NANOpure, Barnstead, Dubuque, IA, USA) was used for liquid chromatography. Separation of curcuminoids was carried out on flash chromatography system (Combiflash® Rf, Teledyne Isco, Lincoln, NE, USA). Silica gel (particle size 35–60 µm) (40 g) flash columns and gold diol (30 g) columns (20–40 µm spherical particle size) were purchased from RediSep® Rf ISCO Inc (Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.2. Isolation

The turmeric oleoresin (100 g) was refluxed with hexane (500 mL) for 4 h for removal of fatty material on a water bath. The extract was filtered and the residue (65 g) was dried under vacuum in a desiccator. The dried reside (30 g) was dissolved in acetone (30 mL) and impregnated with 30 g of silica gel and used for the fractionation of curcuminoids.

2.3. Separation of curcuminoids by 1D hyphenated chromatographic technique

The silica gel impregnated sample (6 g) was subjected to 1D separation using two 40 g silica gel flash columns (particle size 35–60 µm). Both the silica columns were equilibrated with four column volumes of chloroform prior to loading the samples. The curcuminoids were detected at 244 and 360 nm with a peak width of 30 seconds and threshold of 0.05 AU. The separation of curcuminoids was completed in 125 min with a gradient program of solvent A (chloroform) and solvent B (methanol) with a flow rate of 40 mL/min. Four major peaks were separated along with minor peaks (Fig. 1a). The gradient elution of columns was performed according to Table 1. A total of 69 fractions of 42 mL each were collected during the elution process. All fractions were analyzed by HPLC and fractions containing peaks 16–19, 20–22, 25–28 and 33–36 were pooled, concentrated under vacuum to obtain compounds (1–4).

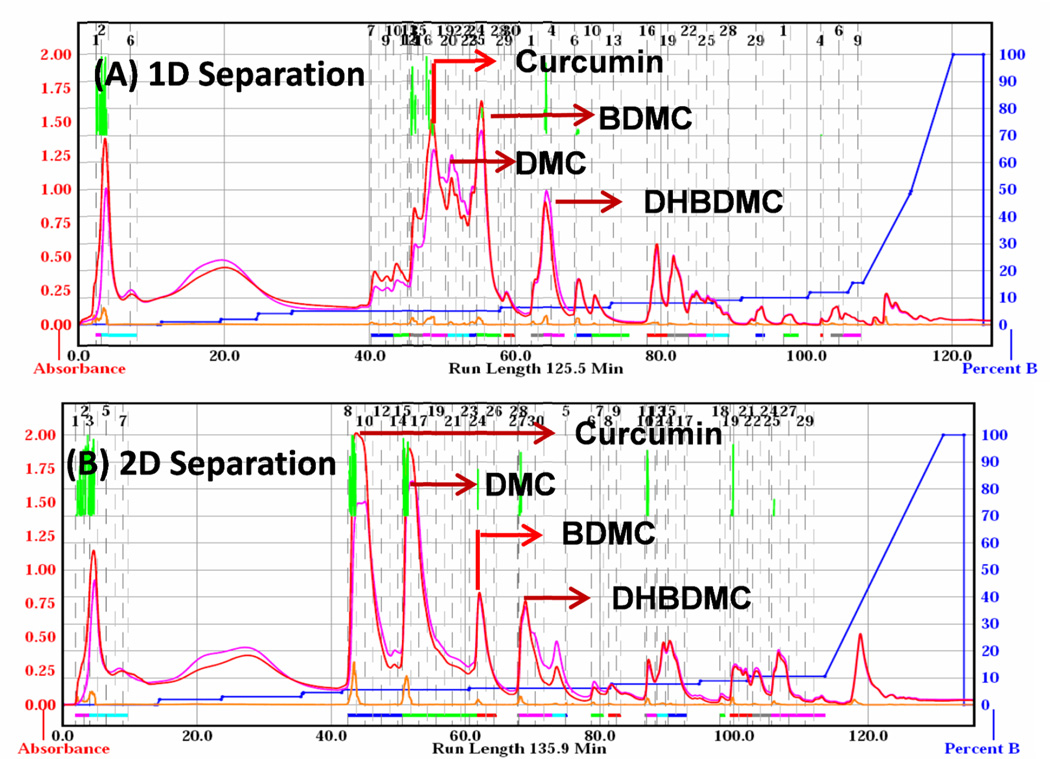

Fig. 1.

Flash chromatographic separation and detection of curcumin (1), demethoxy curcumin (DMC) (2), bisdemethoxy curcumin (BDMC) (3) and dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin (DHBDMC) (4). The separation was achieved by (A). silica column for 1D in 125 min, (B). silica and diol columns for pseudo 2D, using gradient elution of chloroform and methanol. The compounds were detected at 244 and 360 nm simultaneously.

Table 1.

Gradient solvent systems and gradient program used for hyphenated separation of curcuminoids on 1D and pseudo 2D separations

| 1D separation on silica column Pseudo | 2D separation on Silica and Diol columns |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | (A). Chloroform | (B). MeOH | Time | (A). Chloroform | (B). MeOH |

| 0–12 | 100 | 0 | 0–12 | 100 | 0 |

| 12–20 | 100-99 | 0–2 | 12–22 | 100-98 | 2 |

| 20–25 | 99-97 | 2–3 | 22–38 | 98-97 | 2–3 |

| 25–30 | 97-95 | 3–5 | 38–41 | 97-95 | 3–5 |

| 30–58 | 95-93 | 5–7 | 41–60 | 95-93 | 5–7 |

| 58–72 | 93-91 | 7–9 | 60–82 | 93-92 | 7–8 |

| 72–91 | 91-90 | 9–10 | 82–92 | 92-91 | 8–9 |

| 91–100 | 90 | 10 | 91–102 | 91-90 | 9–10 |

| 100–105 | 90-88 | 10–12 | 102–112 | 90 | 10 |

| 105–108 | 88-85 | 12–15 | 112–133 | 90-0 | 10–100 |

| 108–120 | 85-0 | 15–100 | 133 | 0 | 100 |

| 120–125 | 0 | 100 | 133–135 | 0 | 100 |

2.4. Separation of curcuminoids by pseudo 2D hyphenated chromatographic technique

Pseudo two dimensional separation of curcuminoids was carried out using silica (40 g) and diol (30 g) columns in series. Impregnated sample (6 g) was loaded; and column was eluted with chloroform for the separation of curcuminoids as mentioned above. The solvent gradient used for pseudo 2D separation is shown in Table 1. In this experiment, 71 fractions of 42 mL each were collected and analyzed by HPLC; fractions 8–14, 15–23, 24–26 and 28–32 yielded four compounds (Fig. 1b). These grouped fractions were pooled and concentrated under vacuum to obtain crystalized compounds (1–4). Using UV spectral data for compounds (1–4) were tentatively identified as curcumin, demethoxy curcumin (DMC), bisdemethoxy curcumin (BDMC) and dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin (DHBDMC) (Fig. 1b).

2.5 HPLC analysis

All fractions obtained from 1D and pseudo 2D experiments were dissolved in acetone and subjected to HPLC analysis. The HPLC system consisted of Agilent HPLC 1200 series (Foster City, CA) system consisting of a degasser, quaternary pump, auto-sampler, column oven, and photodiode array detector. Elution of curcuminoids was carried out with gradient mobile phases of (A) 3 mM phosphoric acid in water and (B) acetonitrile with a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min at 30 °C using Gemini C18 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) column. Curcuminoids were determined using the gradient: 75% to 45% A from 0 to 5 min, 45% to 20% in 5–12 min, 20–10% in 12–20 min and 10–75% in 20–25 min and maintained for isocratic run for 5 min to equilibrate the HPLC column. Data was processed using the CHEMSTATION software (Agilent, Foster City, CA) (Fig. 2).

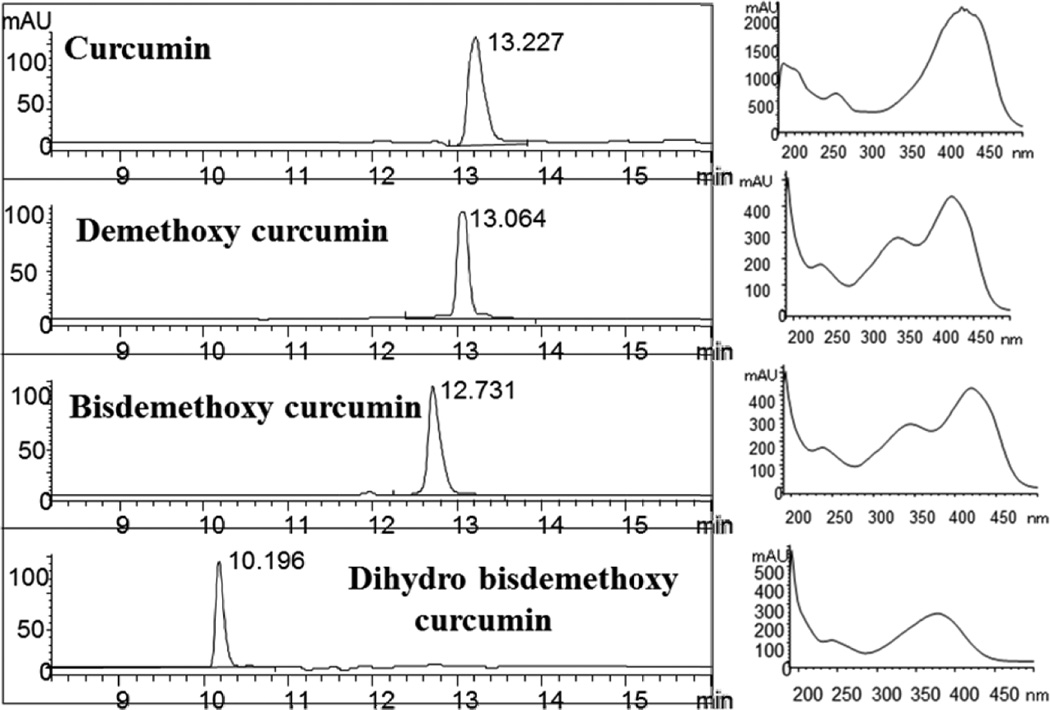

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatograms (left panel) and UV-visible spectra (right panel) of four purified curcuminoids (1–4) obtained by hyphenated technique using LC- pseudo 2D (silica × diol) separation. Curcuminoids were separated using gradient mobile phase as specified in experimental section. Curcumin, demethoxy curcumin and bisdemethoxy curcumin were detected at 425 nm while dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin was detected at 375 nm.

2.6. 1H NMR calibration and Quantization

NMR spectrometer (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) operating at a frequency of 400 MHz for protons equipped with a 5 mm multinuclear inverse probehead and NM-ASC24 sample changer was used for acquisition of NMR spectra. 1H NMR spectra obtained from the single pulse sequence were used to determine the purity of the isolated compounds. Known quantities (3–5 mg) of isolated compounds (1–3) were dissolved in 525 µL of DMSO-d6 separately and compound (4) in 525 µL of acetone-d6 and transferred to 5 mm NMR tubes. An external coaxial glass tube (OD 2 mm) containing 60 µL 0.012% 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionic-(2,2,3,3-d4) acid sodium salt (TSP-d4) solution in D2O was inserted into NMR sample tube for quantitative reference. The TSP-d4 concentration in the tube was pre-calibrated using a separate standard solution. Sufficiently long (16 s) relaxation delay was used to ensure full recovery of magnetization from compound and internal reference (TSP-d4) signals to equilibrium needed for the accurate quantization. All spectra were acquired with a total acquisition time of 4.2 min, 130K data points and 90° pulse length. NMR data were processed using JEOL DELTA software. Purity of compounds were determined by comparing peak integrals of the compounds and the reference after taking into account volume of the sample, number of protons that contribute to peak area and molecular weights of the curcuminoids and the reference compound.

2.7. Characterization of curcuminoids using 13C NMR

13C NMR spectra (acetone d6) of isolated curcuminoids were obtained on a JEOL 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. One dimensional NMR spectra for all the compounds were obtained at 298 K using the singe pulse sequence (for 13C). Spectra were also obtained using the pulse sequence for attached proton test (APT; for 13C) to distinguish different types of carbons based on odd and even multiplicity. All 13C spectra were obtained with proton decoupling during relaxation and acquisition times (Fig. 4). Two Dimensional experiments including HMQC. HMBC and DQFCOSY were also recorded to confirm the structures of the isolated compounds. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

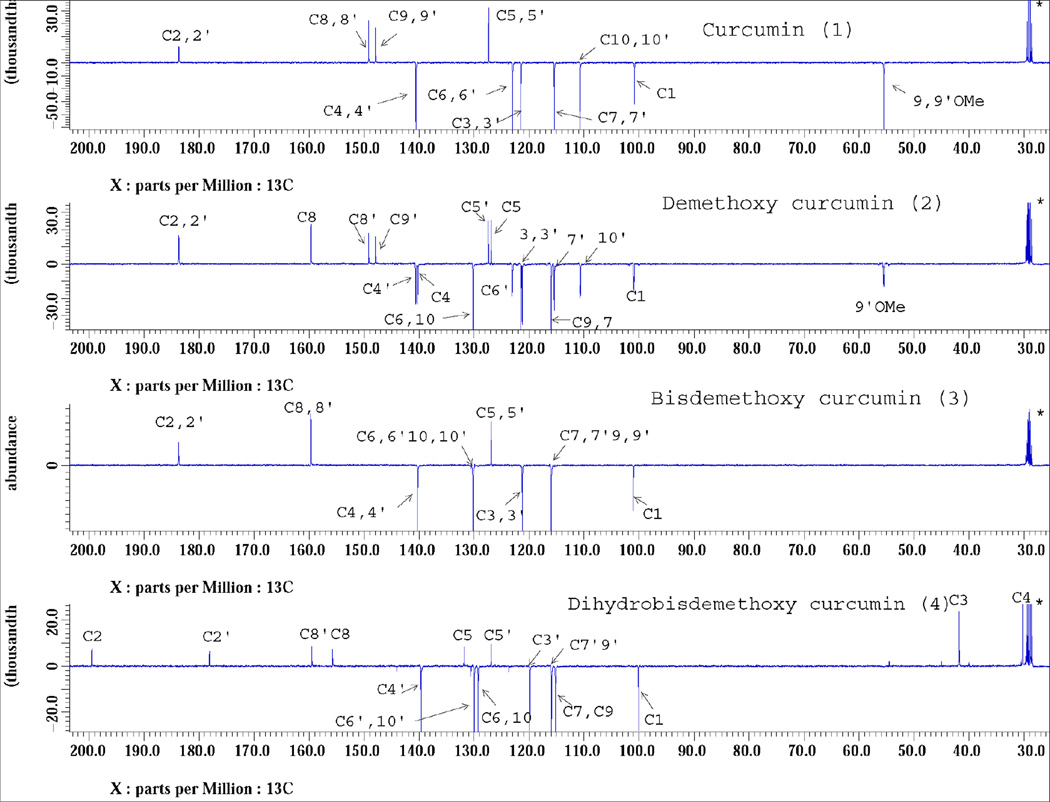

Fig. 4.

13C APT NMR spectra of curcuminoids in acetone-d6 recorded on a JEOL ECS spectrometer operating at 100 MHz. Numbering of the carbon signals corresponds to that shown in Fig. 5.

2.8. LC-MS analysis

All of the compounds were identified by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-time of flight-mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF-MS) (maxis Impact, Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). Isolated compounds were separated on a Kinetex C18 column (1.7 µm, 100 × 2.1mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using an Agilent 1290 UHPLC instrument (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). The separation was carried out at 50 °C with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min using gradient elution with increasing strength of acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. Mass spectral analyses were performed using ESI-Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source in positive ion mode. Capillary voltage was maintained at 2.9 kV, source temperature was set at 200 °C and nitrogen was used as the desolvation gas (12 L/min).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The percent mean and standard deviations for the yield and purity of the isolated compounds were calculated using Microsoft Office Excel, version 2007.

2. Results and discussion

3.1. Separation of curcuminoids by one-dimensional chromatography

Several methods have been reported for the isolation of DMC and BDMC using conventional open columns [4, 17, 29] however these methods are time consuming and require large quantities of solvents [18, 30, 31]. Hence, we have used rapid hyphenated technique for the purification of curcuminoids using 1D and pseudo 2D separation. Turmeric powder has negligible amount of dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin and thus, we have used commercially available turmeric oleoresin to separate minor compounds. Turmeric oleoresin is rich in volatiles and fixed oils (approximately 40%), which were removed by hexane extraction using Soxhlet extraction. The remaining defatted material was fractionated to obtain four curcuminoids. The main objective of the present study is to isolate biologically active curcuminoids by flash chromatography. The elution and separation of curcuminoids was performed as specified in Table 1. Fig. 1A illustrates the separation of curcuminoids using hyphenated 1D (silica gel column) separation. The silica gel impregnated defatted turmeric extract was subjected to flash chromatography on 1D separation using silica gel columns to obtain four major compounds. Fig. 1A shows two major and four minor peaks of significance at 70 min and 80 min. It is well known that, separation using conventional silica gel chromatography seems to be complex and poor resolution. The retention times of relatively major compounds (1–4) are 47, 51, 56 and 65 min respectively. This 1D chromatographic separations of curcuminoids derived from the complex matrices could not give enough separation. This may be due to the presence of various compounds with same polarities as well as relatively low concentration of minor compounds. The yields (w/w) of the compounds (1–4) were found to be 3.16 ± 0.51, 1.67 ± 0.52, 2.06 ± 0.44 and 1.52 ± 0.61% respectively. The yields appeared relatively better. However, the purity of the fractions was not good and each fraction consisted of a mixture of 2–3 compounds due to poor separation.

3.2. Separation of curcuminoids by pseudo two-dimensional chromatography

To improve the separation of curcuminoids, pseudo 2D purification was conducted using two different columns (40g of silica and 30g of diol column) in series. The flash elution and separation was performed using the solvent gradients shown in Table 1. Flow rate and detection wavelengths used were the same as used for 1D separation. However, the run time is a little longer (by 5 mins) compared to 1D separation. Well separated four peaks at retention times of 44, 51, 62 and 70 min were observed using pseudo two dimensional chromatographic separation (Fig. 1B). These fractions were concentrated under vacuum to obtain pure compounds (1–4) with a yields (w/w) of 4.32 ± 0.29, 3.21 ± 0.52, 1.18 ± 0.08 and 0.45 ± 0.11%, respectively. To achieve better separation for curcuminoids, selection of solvents and their gradients is important. In the conventional open column chromatography, most of the commonly used solvents can be used; whereas, in the UV detection technique, the choice of solvents is limited due to the interference of many solvents in absorption. We have tested various combinations of solvents for the separation of curcuminoids; the combinations including hexane: acetone, hexane: ethyl acetate and hexane: acetone did not provide good base line separation. Thus, we have used chloroform: methanol for the separation of curcuminoids.

3.3. HPLC analysis

UV spectra of the compounds were used to determine their identity, and the chromatograms of HPLC analysis for the four isolated compounds are shown in Fig. 2. The absence of other peaks demonstrates the purity of the isolated compounds. The absorption maxima (λmax) of curcumin was observed to be 265, 425nm, demethoxy curcumin 244, 350, 425nm, bisdemethoxy curcumin 244, 350, 425nm and dihydrobisdemethoxy curcumin 260 and 350nm. Saturation of the olefinic bond in DHBDMC has resulted in the loss of conjugation in the molecule as evidenced by the loss of a significant absorbance band at ca. 425nm. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the isolated compounds are given in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, respectively. Results from the spectral analysis of the isolated compounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 were confirmed as curcumin, demethoxy curcumin, bisdemethoxy curcumin and dihydro bisdemethoxy curcumin, respectively. In hyphenated LC separation, UV detection is the most widely used for routine separation of bioactives [32].

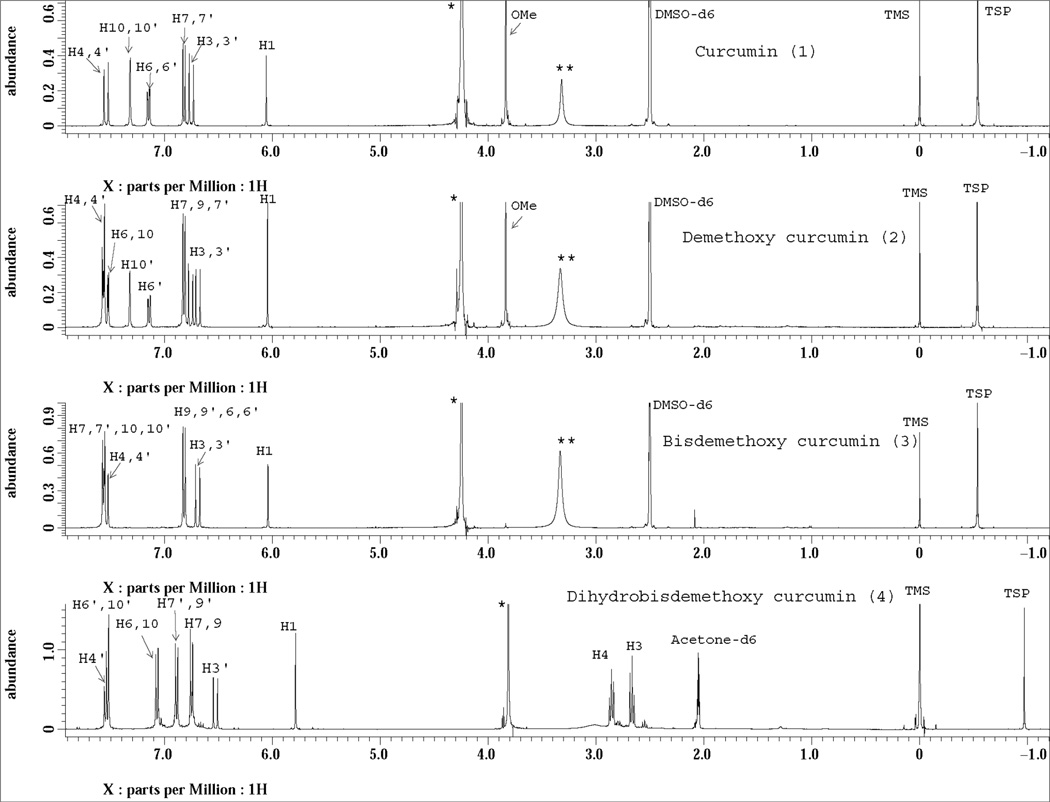

Fig. 3.

1H NMR spectra of curcuminoids (1–4) recorded on a JEOL ECS NMR spectrometer at 400 MHz. Known amount of curcumin, demethoxycurcumin (DMC), bisdemethoxycurucmin (BDMC) were disolved in 525 µL of DMSO-d6, while dihydro bisdemethoxycurcumin (DHBDMC) in 525 µL of acetone-d6 and transferred to 5 mm NMR tubes separatly. A coaxial glass tube (OD 2 mm) containing 60 µL 0.012% 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionic-(2,2,3,3-d4) acid sodium salt (TSP-d4) solution in D2O was inserted into the 5mm NMR tube. TSP-d4 in reusable external tube served as a quantitative reference. The numbering of proton signals corresponds to the numbering in Fig. 5. ** denotes residual water signal from DMSO-d6 and * denotes residual water signal from the D2O solvent in the coaxial tube containing TSP-d4 reference.

3.4. Quantitation of curcuminoidsby qNMR

The isolated compounds were quantitatively analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. 3). Intensity of a particular signal in 1H NMR spectrum is proportional to the number of nuclei that contribute to the signal. The peak areas of NMR signals from non-overlapping regions are chosen for accurate quantitative analysis. Quantitative NMR has been exploited for the analysis of individual components in natural products mixtures [33, 34]. In the present study, we have used 1H NMR spectra for the quantitative analysis of isolated compounds to test the purity, and determine the amount of individual and total curcuminoids present in the turmeric sample. TSP-d4 (3-Trimethyl silyl propionic-(2,2,3,3-d4) acid sodium salt) in D2O was used as a quantitative reference. Fig. 3 shows the quantitative 1H NMR spectra of the four curcuminoids along with the reference TSP-d4 signal from the external co-axial tube. This TSP-d4 signal appears at −0.55 ppm for curcumin, DMC and BDMC whereas in the case of DHBDMC the signal displayed at −0.97 ppm. This difference in chemical shifts arises from the differences in the 2H lock frequency for acetone-d6 and DMSO-d6 solvents. The signal seen for all the four compounds at 0.0 ppm is from tetramethylsilane (TMS) from acetone-d6/DMSO-d6 solvent. All signals in Fig. 3 were assigned to curcuminoids and proton signals at δ6.05 ppm for curcumin, DMC and BDMC and at δ5.78 ppm for DHBDM were used for purity determination. The integral areas of these protons were compared to integral area of the reference TSP-d4 in the same spectrum to calculate the purity; the calculation takes into account the known concentration of TSP-d4, the number of protons that the compound and TSP-d4 signals represent and the weight of isolated compound used to test the purity. While, the purity of curcuminoids (1–4) from 1D flash separation was found to be 23.21 ± 1.02, 23.77 ± 0.76, 40.82 ± 1.22 and 20.65 ± 0.75, respectively, the purity of the same compounds isolated from pseudo 2D separation method was 95.23 ± 3.39, 92.82 ± 0.49, 95.42 ± 1.45 and 92.4 ± 0.44, respectively.

3.5. Characterization of curcuminoids

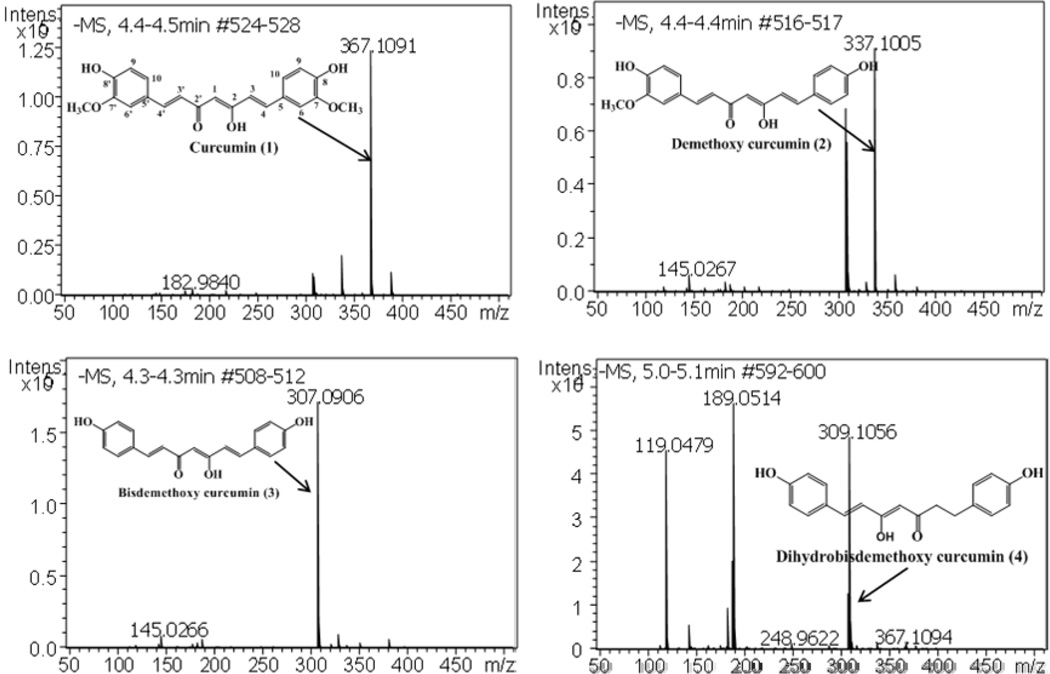

The isolated compounds were characterized using 13C (APT) NMR spectra (Fig. 4) and LC-MS analysis (Fig. 5). APT signals from 13C NMR were assigned to all the carbon signals of curcuminoids (1–4) and the structures were confirmed as curcumin, DMC, BDMC, and DHBDMC, respectively. In addition, results of 2D experiments of four compounds were presented in supplemenarty section. Furthermore, these compounds were analyzed by LC-couple to electrospray ionization quadrupole time of flight to get accurate mass spectra. Fig. 5 shows the negative molecular ions of high resolution accurate mass spectra of curcuminoids (1–4) were confirmed as curcumin (m/z 367.1091), DMC (m/z 337.1005), BDMC (m/z 307.0906) and DHBDMC (m/z 309.1056) respectively.

Fig.5.

Electrospary negative ionization TOF-MS spectra of curcuminoids (1–4) and their structures. The negative molecular ions [M]− of curcuminoids were marked in each spectra for individual compound.

4. Discussion

Conventional separation techniques such as open liquid chromatography and chromatography using normal or reversed phase are associated with a number of limitations. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography methods offer a number of advantages for the separation of compounds from complex sample matrix over conventional methods. In contrast to multidimensional LC separation techniques, particular fraction of the first-dimension is further fractionated on the second-dimension column to obtain high pure compounds [35].

In the present study, pseudo two dimensional LC (silica × diol) separation techniques provide increased peak capacities, as well as fast separation, without loss of compounds as compared 1D chromatography. Curcuminoids extracted from turmeric consists of complex constituents with wide range of concentrations. In order to achieve good separation of curcuminoids, sample to gel ratio was maintained 1:10. By maintaining 1:10 ratio mg to grams quantity of sample can be separated by using appropriate size of columns. This pseudo twodimensional separation provides, where particular curcuminoids of interest in the first (silica) column is stored and separated in second (diol) column. In order to achieve good separation of the co-eluting peaks, additional separation technique was applied to increase peak purity. Diol functionalized silica gel is less polar and has a lower retention time than normal phase silica gel [36]. The diol columns used in the present study were reused up to 8–10 times. The use of two diol columns in series is not recommended due to complexity of sample matrix. Moreover, the activation and regeneration of diol columns will be challenging. We have also attempted to separate curcuminoids using amino columns, but the separation was very poor and most of the curcuminoids were not eluted from the column. Recently, certain compounds are resolved by two independent separation techniques featuring the same mechanism, especially reversed-phase LC × reversed-phase LC systems [37, 38]. In these cases, the two-dimensional separation is based on the use of different organic modifiers and/or RPLC columns with different properties. This approach gives good separation for micro quantities in analytical HPLC, but not easy to apply for preparative scale (mg to grams) separation and also manual collection of each peak will be tedious.

Jandera and Hajek [39] reported the better separation selectivity of phenolic acids on reversed phase diol column and those were separated in less than 5 min with 2% buffered acetonitrile as the mobile phase. Flavonoids are more strongly retained and better resolved on the diol column as compared PEG column in the HILIC mode containing approximately 98% acetonitrile [40]. Most of the reported 2D separations were either LC × LC or GC × GC for the separation solute in analytical scale [41–43]. However, in the present study curcuminoids were separated successfully on silica and diol at preparative level for the first time. Therefore the use of two different separative modes in sequence with one common mobile phase in automated flash system yielded mg to grams of curcuminoids. Diol columns offer an alternative to normal phase columns for difficult separations of low to medium polarity samples [44]. In normal phase mode the diol stationary phase is a versatile alternative to silica. In bonded phase’s, hydroxyl groups provide good selectivity without excessive retention, since hydrogen bonding with the diol layer is not as strong as with the silanols on a silica surface. In addition, diol columns also provide improved reproducibility when compared with regular silica. Interestingly diol columns are suitable for separations using reversed phase and normal phase solvents.

During last two decades, proton NMR spectroscopy is emerged as a powerful analytical tool for metabolomics studies [45–48] and also purity of compounds can be determined without any specific reference standard [49]. Goren et al., [50] reported the quantitation of curcumin by NMR and LC-MS with 1,3,5-trimethoxy benzene as internal reference. Using this technique only curcumin has been quantified. The developed quantitation methods reported herein can be used for routine identification and quantitation of curcuminoids in biological samples in less than 5 min.

3. Conclusion

Using pseudo two-dimensional chromatography four curcuminoids were isolated in preparative scale from turmeric. The developed method is a rapid and economical technique to obtain minor curcuminoids with high purity using routinely used solvents by maintaining sample to gel ratio of 1:10. These results indicate that the present pseudo 2D separation method could improve the resolution and separation time, and represents a practical approach to resolve problems caused by peak overlap. Moreover, the quantitation by NMR is fast and requires less than 5 min for each sample. The developed qNMR technique could be used for NMR quantitation for the purpose of quality control and standardization of natural products and medicines without the need for reference marker standards.

Supplementary Material

Highlights of research.

Pseudo 2D separation of curcuminoids was developed for the first time

Developed method is rapid to get preparative levels of curcuminoids

Purity of curcuminoids were measured by qNMR for the first time

High purity compounds (92.4–95.45%) were isolated

Acknowledgements

This project is based upon the work supported by the USDA-NIFA No. 2010-34402-20875, "Designing Foods for Health" through the Vegetable & Fruit Improvement Center and NIH grant – DHHS-NIH-NCI 1R01CA168312-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jayaprakasha GK, Jagan Mohan Rao L, Sakariah KK. Trends Food Sci.Tech. 2005;16:533–548. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammon HPT, Safayhi H, Mack T, Sabieraj J. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993;38:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90005-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt PR, Katz S, Kirshoff R. Digest Dis. Sci. 2005;50:2191–2193. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayaprakasha GK, Jagan Mohan Rao L, Sakariah KK. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:3668–3672. doi: 10.1021/jf025506a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radhakrishna Pillai G, Srivastava AS, Hassanein TI, Chauhan DP, Carrier E. Cancer Lett. 2004;208:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorai T, Aggarwal BB. Cancer Lett. 2004;215:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Best L, Elliott AC, Brown PD. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;73:1768–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yodkeeree S, Ampasavate C, Sung B, Aggarwal BB, Limtrakul P. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;627:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luthra PM, Kumar R, Prakash A. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2009;384:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peret-Almeida L, Cherubino APF, Alves RJ, Dufosse L, Gloria MBA. Food Res. Int. 2005;38:1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roughley PJ, Whiting DA. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1973;1:2379–2388. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oka K, Dobashi Y, Ohkuma T, Hara S. J. Chromatogr. 1981;217:387–398. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue K, Nomura C, Ito S, Nagatsu A, Hino T, Oka H. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:9328–9336. doi: 10.1021/jf801815n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel K, Krishna G, Sokoloski E, Ito Y. J. Liquid Chromatogr. R T. 2000;23:2209–2218. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaprakasha GK, Jagan Mohan Rao L, Sakariah KK. No. 194592. Indian Patent. 1998

- 16.Ha YW, Kim YS. Phytochem. Analysis. 2009;20:207–213. doi: 10.1002/pca.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi S, Huang K, Zhang Y, Liu S. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2008;60:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laidman DL, Hall GS. Adsorption column chromatography of tocopherols. In: Donald BM, Lemuel DW, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 1971. pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marston A, Hostettmann K. Planta Med. 2009;75:672–682. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaroszewski JW. Planta Med. 2005;71:795–802. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiborr C, Eckert G, Rimbach G. J. Frank. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:1917–1925. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scotter MJ. LWT - Food Sci. Tech. 2009;42:1345–1351. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vial J, Jardy A. J. High Res. Chromatog. 1999;22:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 24.M A. 18.0, Official Analytical Methods of the American Spice Trade Association. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: American Spice Trade Association; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiserodt R, Hartman TG, Ho C-T, Rosen RT. Journal of Chromatography A. 1996;740:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jandera P. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1255:112–129. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little EL, Jeansonne MS, Foley JP. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svec F. The J. Edu. 1997;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang L-H, Jong T-T, Huang H-S, Nien Y-F, Chang C-MJ. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2006;47:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renold P, Madero E, Maetzke T. J Chromatogr. A. 2001;908:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou D-Y, Chen D-L, Xu Q, Xue X-Y, Zhang F-F, Liang X-M. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2007;43:1692–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung ES, Synovec RE. Anal. Chem. 1986;58:1237A–1256A. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siciliano C, Belsito E, De Marco R, Di Gioia ML, Leggio A, Liguori A. Food Chem. 2013;136:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauli GF, Gödecke T, Jaki BU, Lankin DC. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:834–851. doi: 10.1021/np200993k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Killgore JK, Villaseñor SR. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996;739:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kažoka H. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1189:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X, Kong L, Su X, Fu H, Ni J, Zhao R, Zou H. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1040:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu L, Chen X, Kong L, Su X, Ye M, Zou H. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1092:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jandera P, Hájek T. J. Sep. sci. 2009;32:3603–3619. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jandera P, Hájek T, Škeříková V, Soukup J. J. Sep. Sci. 2010;33:841–852. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adahchour M, Beens J, Vreuls RJJ, Brinkman UAT. Trac-Trend Anal. Chem. 2006;25:438–454. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Kong L, Lei X, Hu L, Zou H, Welbeck E, Bligh S, Wang Z. J. Chromatogr. A. 2009;1216:2185–2191. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoll DR. Analy. Bioanalytical chem. 2010;397:979–986. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de la Puente M, Soto-Yarritu PL, Anta C. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang B, Powers R. Future. 2012;4:1273–1306. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HK, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Trends Biotech. 2011;29:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinette SL, Brüschweiler R, Schroeder FC, Edison AS. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2011;45:288–297. doi: 10.1021/ar2001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho HR, Wen H, Ryu YJ, An YJ, Kim HC, Moon WK, Han MH, Park S, Choi SH. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chauthe SK, Sharma RJ, Aqil F, Gupta RC, Singh IP. Phytochem. Analysis. 2012;23:689–696. doi: 10.1002/pca.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gören AC, Çıkrıkç ı S, Çergel M, Bilsel G. Food Chem. 2009;113:1239–1242. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.