Abstract

Background

Xerostomia (dry mouth) after head/neck radiation is a common problem among cancer patients. Quality of life (QOL) is impaired, and available treatments are of little benefit. This trial determined the feasibility of conducting a sham-controlled trial of acupuncture and whether acupuncture could prevent xerostomia among head/neck patients undergoing radiotherapy.

Methods

A sham controlled, feasibility trial was conducted at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai, China among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy. To determine feasibility of a sham procedure, 23 patients were randomized to real acupuncture (N = 11) or to sham acupuncture (N = 12). Patients were treated 3 times/week during their course of radiotherapy. Subjective measures were the Xerostomia Questionnaire (XQ) and MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for Head and Neck Cancer (MDASI-HN). Objective measures were unstimulated whole salivary flow rates (UWSFR) and stimulated salivary flow rates (SSFR). Patients were followed for 1 month after radiotherapy.

Results

XQ scores for acupuncture were significantly lower than sham controls starting in week 3 and lasted through the 1-month follow-up (all P’s < 0.001 except for week 3, which was 0.006), with clinically significant differences as follows: week 6 – RR 0.28 [95% CI, 0.10, 0.79]; week 11- RR 0.17 [95% CI, 0.03, 1.07]. Similar findings were seen for MDASI-HN scores and MDASI-Intrusion scores. Group differences for UWSFR and SSFR were not found.

Conclusions

In this small pilot study, true acupuncture given concurrently with radiotherapy significantly reduced xerostomia symptoms and improved QOL when compared with sham acupuncture. Large-scale, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are now needed.

Keywords: Acupuncture, xerostomia, head and neck cancer, quality of life, complementary medicine

Introduction

Most patients diagnosed with head/neck cancer receive radiotherapy as part of their cancer treatment. Xerostomia (dry mouth) is a common, often debilitating, side effect of radiotherapy in this population, occurs to some degree in up to 100% of patients, and can severely impair quality of life (QOL) (1, 2). Patients can experience taste aberrations, dysphagia, odynophagia, difficulty sleeping and speaking, and loss of appetite. Due to the decrease in saliva, there can be a reduction in the natural inhibition of bacterial growth in the oral cavity, resulting in increases of caries-forming microbes that can cause bone infection and irreversible nutritional deficits (3).

Treatment for radiation-induced xerostomia, for the most part, is palliative. Approaches such as saliva substitutes, chewing gum, sialogogue lozenges, and pilocarpine have been attempted with limited benefit (4–13). Amifostine reduces the incidence and severity of radiation-induced xerostomia but is not universally available, requires parenteral administration, and has potential unpleasant side-effects (9).

Multiple clinical trials indicate acupuncture can benefit patients with head and neck cancer who have developed radiation-induced xerostomia (14–26). Studies conducted by different groups of investigators both in the United States and Europe have demonstrated positive results. Some have shown relief of symptoms in as few as 5 treatments (14), with benefits lasting up to 3 years (15). No previous sham-controlled, randomized trials, however, have explored whether acupuncture can prevent xerostomia.

We previously conducted a randomized trial to determine the effects of acupuncture for preventing the development of xerostomia among cancer patients undergoing conventional radiotherapy to the head/neck where an acupuncture group was compared to usual care (27). Group differences in xerostomia symptoms, salivary flow, and QOL emerged as early as 3 weeks into radiotherapy and remained statistically and clinically significantly different 6 months after the end of radiotherapy. Although primarily a feasibility trial, this second trial compared true acupuncture with sham acupuncture as a secondary aim. We hypothesized acupuncture would prevent the development of xerostomia and diminish its severity. We also hypothesized participant blinding would be maintained throughout the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a 2-arm, randomized, sham-controlled feasibility study. It was approved by Institutional Review Boards at both MD Anderson Cancer Center and Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center; however, all patients were treated in China. Potential participants were identified by faculty in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Fudan, eligibility was assessed, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were recruited between February and August, 2009. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00862550.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were: >18 years; nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC); scheduled for IMRT; intact parotid and submandibular glands; Zubrod performance status of 0, 1, or 2. Patients were excluded if they had a history of xerostomia; suspected or confirmed physical closure of salivary gland ducts on either side; known bleeding disorders and taking heparin or warfarin; history of cerebrovascular accident or spinal cord injury; or if they had taken any drug or alternative medicine in the past 30 days that could affect salivary function or were planning to take such a substance during the study. Patients also had to be acupuncture naive and receive a mean dose of 25 Gy or more bilaterally to the parotids.

Procedures

After collecting baseline measures, patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Patients assigned to G1 had real acupuncture on the same day but prior to radiation 3 days/week during a 6-week course of radiotherapy (18 treatments total). Patients assigned to G2 underwent sham acupuncture 3 days/week during a 6-week course of radiotherapy (18 treatments total). Group assignments were allocated using a form of adaptive randomization, minimization, because simple randomization could result in covariate imbalances (28). Patient characteristics used for group assignment were stage of disease, age, and mean planned bilateral parotid dose. Self-report questionnaires and sialometry were collected at baseline, weekly during the course of radiotherapy, and 1 month after the end of radiotherapy.

Real acupuncture

All treatments were given by a hospital credentialed acupuncturist with over 35 years of experience. Patients were treated in a supine position. Standardized techniques for point location were used (29, 30), and needle insertion endpoints were standard recommended depth of insertion(29, 30) or achievement of De Qi sensation. Body points included Ren 24, Lung 7 (LU 7), and Kidney 6 (K 6). Ear points included Shenmen, Point Zero, Salivary Gland 2-prime (SG 2’), and Larynx. Except for Ren 24, which is located in the midline, all points were treated bilaterally, and all needles were removed after 20 minutes.

Patients receiving real acupuncture also had one sham needle at Gallbladder 32 (GB 32), located 5 cun (1cun=1 fingerbreadth) above the popliteal crease on the lateral aspect of the right knee. This was to help maintain participant blinding.

Sham acupuncture

Sham treatment was given according to the same schedule as real acupuncture. A non-penetrating needle device validated by Park and colleagues was used (31, 32).

Location 1 - sham needle at inactive point located 0.5 cun below and 0.5 cun lateral to Ren 24 on the chin.

Location 2 - sham needle at inactive point located 0.5 cun radial and 0.5 cun proximal to Sanjiao 6 (SJ 6) between the SJ and Large Intestine (LI) channels (bilateral upper extremities).

Location 3 - sham needle at inactive point located 2 cun above Sham Location 2 between the SJ and LI channels and between LI 7 and LI 8 (bilateral upper extremities).

Location 4 - sham needle at inactive point located 1.0 cun below and 0.5 cun lateral to Stomach 36 (ST 36), between the ST and GB channels (bilateral lower extremities).

Three real acupuncture needles were inserted on the helix of each ear (6 total). One real acupuncture needle was also inserted at GB 32 above the right knee. This point is not indicated for dry mouth and was used to elicit De Qi sensation in the control group. The needles were Seirin, 36 gauge×30 mm for body points and 40 gauge×15 mm for ear points.

Measures

The Xerostomia Questionnaire (XQ) is an 8-item survey previously validated in several cohorts (33, 34). After adding item scores, the sum is transformed linearly to produce a final summary score between 0 and 100. Higher scores represent more severe xerostomia. Eisbruch (33) and Pacholke (34) suggest clinical relevance is shown with XQ scores ≤ 30 corresponding to mild to no symptoms of xerostomia.

On a 0–10 numeric rating scale, the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Head and Neck (MDASI-HN) measures both the severity of symptoms and the interference of symptoms with patients’ daily activities. One question specific to dry mouth was removed in the symptom total score in order to have a measure that assessed non dry mouth-related symptoms. The MDASI-HN includes 9 additional head/neck specific items. The instrument has been validated in a cohort of over 200 patients and found to be highly reliable (35).

Salivary flow was measured using both unstimulated whole salivary flow rates (UWSFR) and stimulated salivary flow rates (SSFR). Sialometry procedures have been previously reported (36).

Patient blinding was also assessed. Participants were asked in the middle of the treatment course and at the end whether they thought they were in the real or sham acupuncture group, or if they could not tell.

Statistical Analyses

Although the primary objective for this sham-controlled trial was feasibility, the primary outcome was the XQ and maintenance of blinding. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses subjective outcomes as the standard for drug approval in xerostomia treatment. Since this was a feasibility study, no formal power calculations were made; however, our primary criteria for feasibility success was participation rates of at least 40% among eligible patients approached, a drop-out rate less than 30%, and all patients believing they were receiving real acupuncture.

We used SAS PROC MIXED (37) procedure to run linear mixed models with the longitudinal data from week 1 to week 11. In these models, the intercept was random effect and covariance was unstructured. Time effect (week) was treated as a continuous variable. As the outcomes were curvilinear, we examined the curvature of the outcomes over time by adding a quadratic term for time to the model. Examination of group differences at each week was conducted by using the LSMEAN command in the PROC MIXED procedure. In order to ensure the outcomes from the LSMEAN analyses from the mixed model procedure were similar to conducting a more simplistic general linear model (GLM) analyses at each time point separately, we also ran the GLM procedure in SAS at each time point, controlling for baseline levels of the respective outcome variable. The trends for the outcomes remained the same. However, because the study used a repeated measures design, the statistical tests presented are from the mixed model analyses. The tables and figures show the raw means of the outcomes for better interpretation of the data. We also conducted sub-analyses of XQ scores >30 (signifying clinically significant levels of xerostomia) at 6 and 11 weeks using chi-square tests. Although there were no group differences in age, stage, dose of radiotherapy, and chemotherapy administration the analyses were also conducted controlling for these variables. The findings remained the same in terms of the significant outcomes.

RESULTS

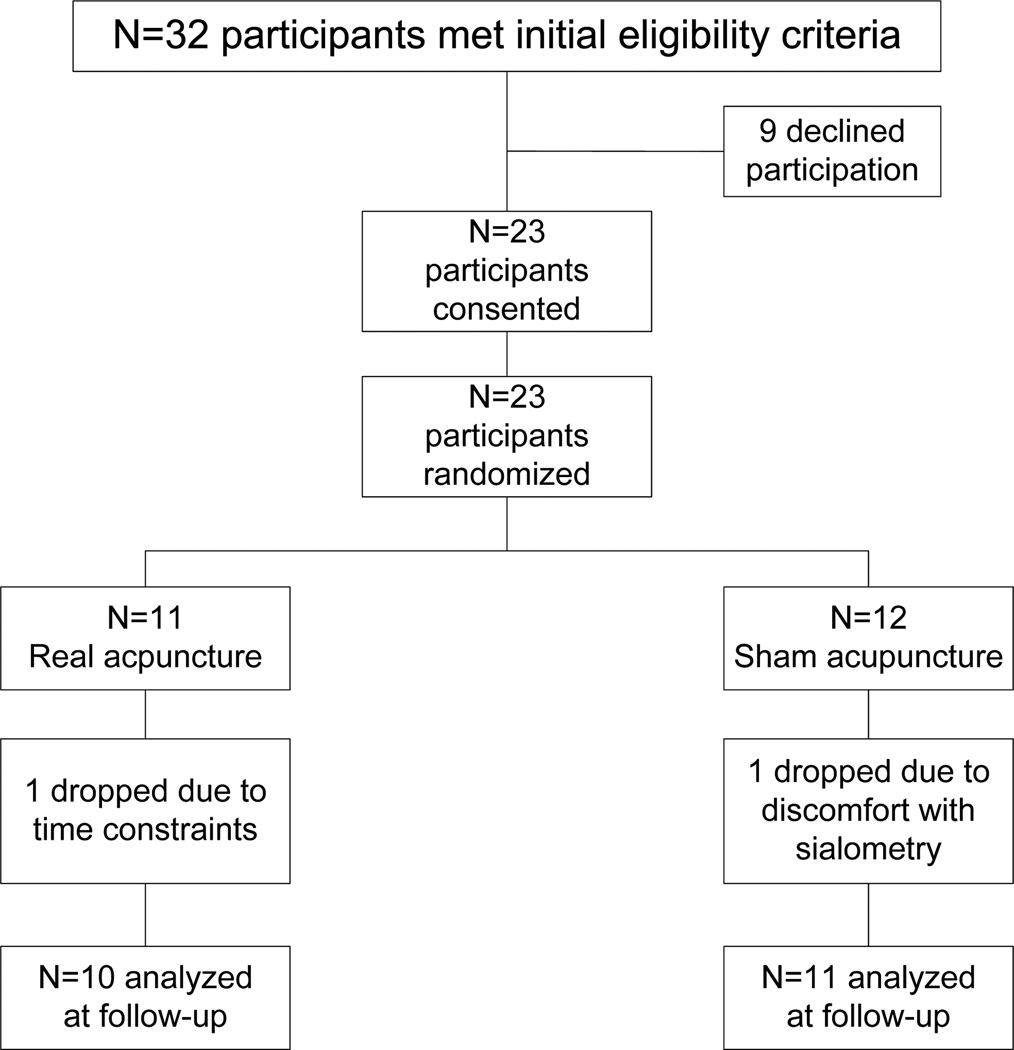

Of 32 eligible patients approached, 23 consented and were randomly assigned to real or sham acupuncture (72% acceptance rate, Figure 1). One patient in the sham group stopped receiving radiotherapy after 4 weeks but was included in the data analyses for the time points for which they provided data. Otherwise, complete data was available at each time point for all patients. As can be seen in Table 1, the groups were balanced on medical and demographic characteristics. Three patients received only radiation, seven patients underwent induction chemotherapy prior to radiation, eight patients underwent induction and concurrent chemotherapy with radiation, and three patients underwent concurrent chemotherapy with radiation. There were no group differences on chemotherapy regimen. Compliance with the acupuncture treatments among the 20 patients who remained in the trial and underwent a full course of radiotherapy was very high (14 patients received all treatments, four received all but one, and two received all but two), with no group differences. There were no adverse events associated with either the real or sham acupuncture. The sham group remained blinded, with all patients in both groups believing they received real acupuncture.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics

| Characteristic | Acupuncture (n=10) |

Control (n=11) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.8 (13.3) | 47.2 (13.6) | 0.81 |

| Median (range) | 42.9 (30.3–71.3) | 47.2 (20.4–70.4) | |

| Gender n (%) | 0.48 | ||

| Male | 9 (90.0) | 11 (100.0) | |

| Female | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stage n (%) | 0.78 | ||

| I | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| II | 1 (10.0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| III | 8 (80) | 7 (63.6) | |

| IV | 1 (10) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Radiation Dose (Gy) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 67.7 (2.2) | 66.7 (7.8) | 0.7 |

| Median (range) | 66.0 (66.0–70.4) | 70.0 (44.0–70.4) | |

| Type of Chemotherapy N (%) | 0.74 | ||

| Radiation Only | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Induction Chemo | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Concurrent Chemo | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Induction and Concurrent Chemo | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | |

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Xerostomia

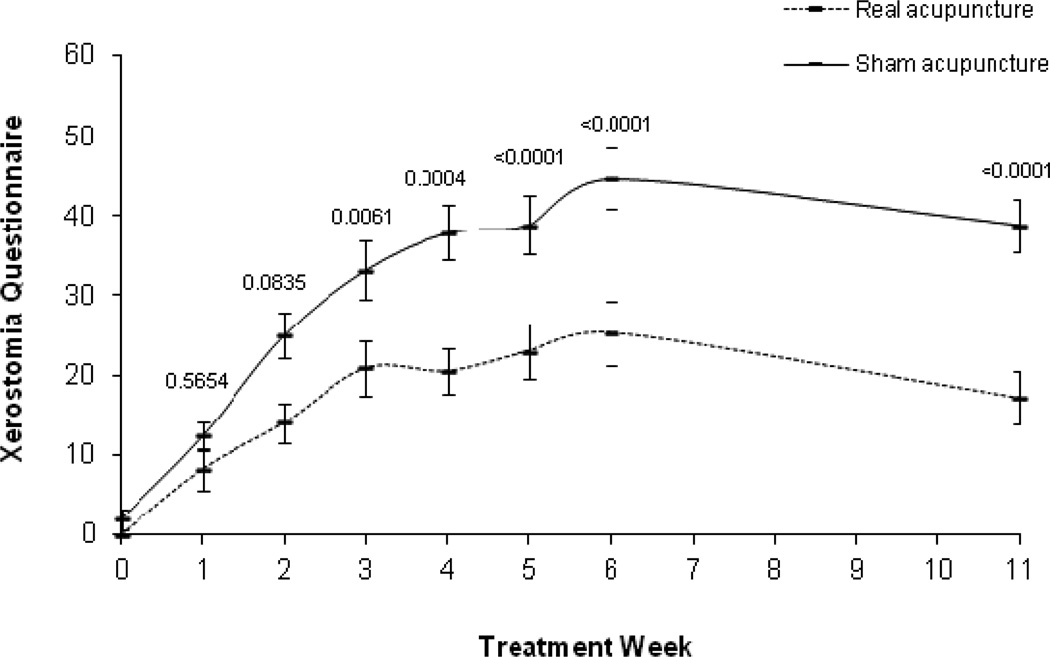

Analyses of XQ data revealed a significant main effect of time (p<0.0001), a group by time interaction (p<0.0001), a quadratic time effect (p<0.0001), and group by quadratic time interaction effect (p=0.0086). Figure 2 shows XQ outcomes over time (see Figure 2 for raw means over time). In the LSMEAN analysis, mean comparisons by week showed the control group had significantly higher XQ scores starting in week 3 that remained through week 11. The absolute differences between the groups increased over time, with the greatest difference at week 11 (group difference = 20.1) (see Table 2 for the raw means over time and p values). Examination of XQ scores >30 by group using chi-square analyses showed by week 6, the real acupuncture group had significantly fewer patients with scores > 30 (real acupuncture 25%; sham acupuncture 87.5%, P = 0.006; RR 0.29 [95% CI, 0.10, 0.79]), and this continued through week 11 (real acupuncture 12.5%; sham acupuncture 75%, P=0.02; RR 0.17 [95% CI, 0.03, 1.07]).

Figure 2.

Xerostomia Questionnaire raw means and standard error bars over time. P values at each time point are based on the LSMEAN group comparison analyses from the mixed model analyses.

Table 2.

Raw means, (standard errors), and p-values* by group across time

| Week 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XQ | Real Acup | 0 (0) | 8.3 (2.6) | 14 (2.5) | 20.9 (3.3) | 20.5 (2.8) | 23 (3.5) | 25.3 (4.1) | 17.1 (3.3) |

| Sham Acup | 1.9 (1.3) | 12.4 (1.8) | 25 (2.8) | 33.2 (3.6) | 37.8 (3.5) | 38.9 (3.6) | 44.6 (3.8) | 38.9 (3.3) | |

| P-value | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| MDASI SYM | Real Acup | 0.4 (0.2) | 5.9 (1.2) | 8.1 (1.4) | 11.8 (1.7) | 12 (2.3) | 15.1 (2.3) | 15.2 (2.2) | 4.8 (1.3) |

| Sham Acup | 2.4 (0.8) | 6.8 (1.5) | 10.9 (1.9) | 14.6 (2.1) | 15.4 (1.7) | 17.9 (2.5) | 21.1 (3.8) | 4.7 (1.4) | |

| P-value | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.57 | |

| MDASI INT | Real Acup | 0.3 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.9) | 6.5 (1.0) | 7 (0.9) | 8.6 (1.7) | 10.3 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.1) |

| Sham Acup | 0.7 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.7) | 7.2 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.7 (1.5) | 12.6 (1.4) | 14 (2.0) | 5.8 (1.3) | |

| P-value | 0.24 | 0.2 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.22 | |

| MDASI HN | Real Acup | 0.8 (0.4) | 4.4 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 17 (2.1) | 17.9 (1.7) | 21.9 (2.4) | 25.9 (1.9) | 11.1 (1.1) |

| Sham Acup | 1.2 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.8) | 12.7 (1.5) | 20.2 (1.9) | 25.6 (1.5) | 28.5 (2.0) | 36.8 (2.8) | 14.9 (1.4) | |

| P-value | 0.56 | 0.91 | 0.13 | 0.004 | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | |

| UWSFR | Real Acup | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.1) | ||

| Sham Acup | 2.0 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | |||

| P-value | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.88 | |||

| SSFR | Real Acup | 4.2 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.2) | ||

| Sham Acup | 3.4 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.3) | |||

| P-value | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

P values at each time point are based on the LSMEAN group comparison analyses from the Mixed Model procedure.

Acup = Acupuncture; XQ = Xerostomia Questionnaire; MDASI = MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; SYM = Symptom subscale; INT = Interference subscale; HN=Head and Neck subscale; UWSFR = unstimulated whole salivary flow rates; SSFR = stimulated salivary flow rates

Symptom burden

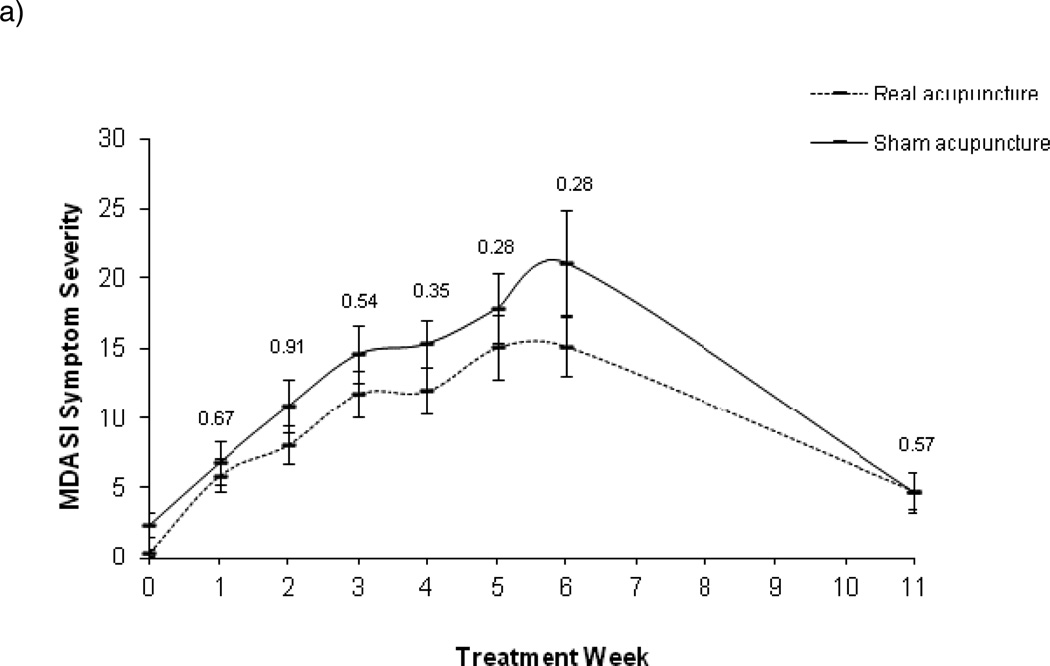

For MDASI Symptom Severity, the main effect of time and the quadratic term of time were significant (both p<0.0001), with no significant group by time interaction (P=0.098), and a marginally significant group by quadratic time interaction effect (P=0.073). However, there were no significant group differences at any of the time points (Figure 3a). In the MIXED model of Interference scores (Figure 3b), the main effect of time and the quadratic term of time were significant (both p<0.0001); but no group by time interaction (P=0.39) and no group by quadratic time interaction effect (P=0.38). In the pos-hoc analyses, group differences were significant at week 3 through week 6. Similar results were found for Head/Neck subscale as for the XQ. Examination of the Head/Neck subscale revealed a significant main effect of time (P<0.001), a group by time interaction (P=0.0003), a time quadratic effect (P<0.0001), and a group by quadratic time interaction effect (P=0.0008). In the LSMEAN analysis, mean comparisons by week showed the control group had significantly higher Head/Neck scores starting in week 3 that remained through week 6 (Figure 3c). The absolute mean difference between the groups increased overtime until 6 weeks, with the greatest difference at week 6 (group difference=8.53) (see Table 2 for the raw means over time and p values).

Figure 3.

MD Anderson Symptom Inventory raw means and standard error bars over time (a. Symptom Severity; b. Interference; c. Head and Neck Subscale). P values at each time point are based on the LSMEAN group comparison analyses from the mixed model analyses.

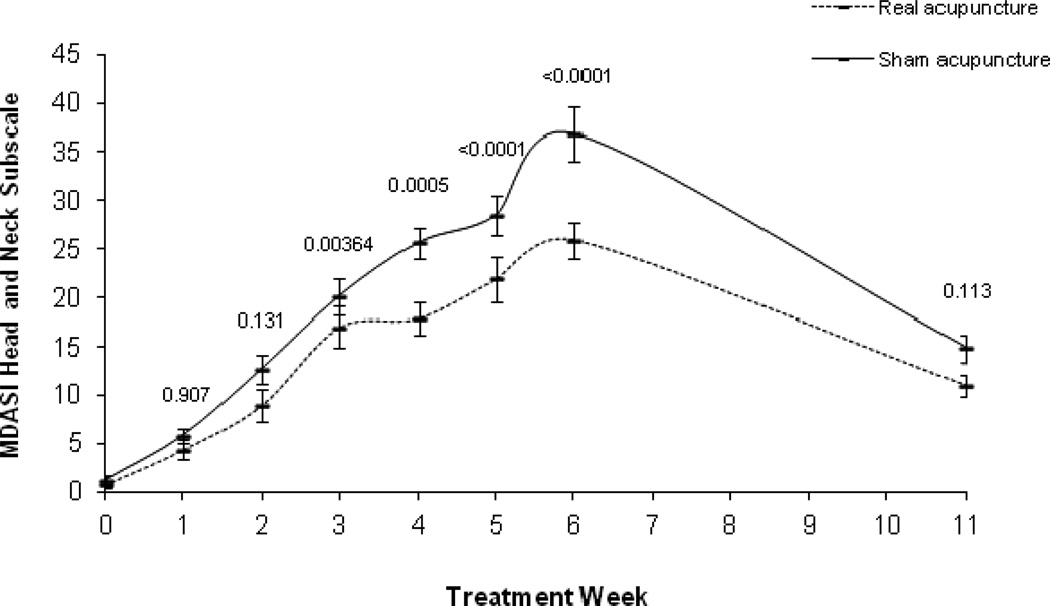

Sialometry Outcomes

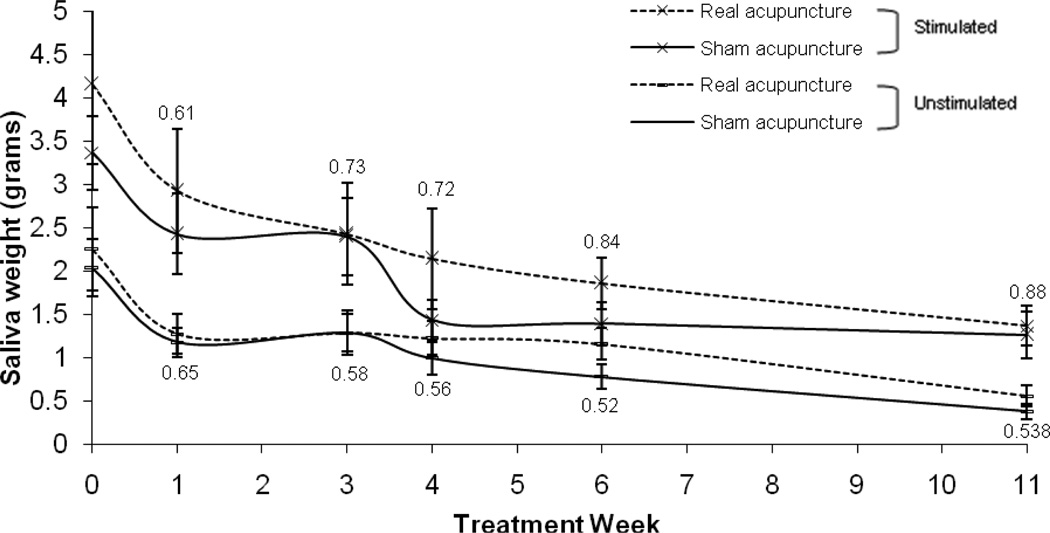

In the MIXED model analyses of UWSFR and SSFR, there was not a significant quadratic time effect (UWSFR: P=0.15; SSFR: P=0.10); therefore the quadratic term of time was not included in the final model. There was a significant time main effect for both UWSFR and SSFR (p<0.0001 for both outcomes), showing that both UWSFR and SSFR decreased overtime. Owing to the small sample size and high level of variance for the sialometry measures, the group by time interaction did not reach significance (UWSFR: P=0.81; SSFR: P=0.61) and there were no group differences at any time point (see Figure 4 and Table 2 for the raw means over time and p values).

Figure 4.

Stimulated and unstimulated whole salivary flow rates raw means and standard error bars over time. P values at each time point are based on the LSMEAN group comparison analyses from the mixed model analyses.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized, sham-controlled study to investigate whether or not the use of acupuncture given during a course of radiotherapy can reduce the development and severity of xerostomia. For self-report measures, group differences emerged as early as week 3, and remained significant at 1 month after the end of radiotherapy, even without additional acupuncture. Only 25% of patients in the real acupuncture group reported clinically significant symptoms 1 month after the end of radiotherapy versus almost 90% in the sham-acupuncture group.

Findings from this trial are consistent with a previous larger study conducted by our group comparing an acupuncture group versus standard care control group of patients undergoing conventional radiotherapy (27). Even though group differences did not reach significance for the sialometry outcomes, the shape of the curves were remarkably similar to our previous trial. It is particularly noteworthy that benefit of acupuncture was found for patients undergoing IMRT as most patients will undergo this form of treatment in the United States, and it is becoming more commonly used in China.

The FDA recommends subjective outcomes as the standard for drug approval in xerostomia trials. Because both basal and stimulated salivary flow rates vary significantly among individuals, and there is no minimum salivary flow rate associated with xerostomia symptoms, subjective sensations of oral dryness is not always a reliable indicator of salivary flow rate. Impaired salivary gland function can exist with or without the sensation of oral dryness (38). Thus, it is important to note that both the objective and subjective outcomes followed a similar pattern, with significant differences in saliva flow between the two groups emerging as early as 3 weeks into treatment and remaining 1-month later. Importantly, XQ scores from this sham-controlled trial with a very small sample size were similar to the previous larger study we conducted (27).

Putative biological mechanisms involved in the treatment of xerostomia with acupuncture are not well understood, but some research showed that local blood flux increased significantly in the skin overlying the parotid glands following acupuncture (17). Later studies (21, 22) demonstrated that acupuncture caused increased concentrations of both vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and calcitonin gene-related peptide in the saliva.

There are a number of factors that limit the interpretation of the findings from this trial. Due to the small sample size, the findings need to be interpreted with caution. However, the findings are remarkably similar in terms of the XQ outcomes to the previous larger trial we conducted comparing acupuncture versus standard care (27). Additional research is now needed to establish the stability of the findings and to determine whether group differences will become significant for the sialometry outcomes with a larger sample size. We also did not follow the patients beyond 1 month after the end of radiotherapy, so the long-term benefits of acupuncture versus placebo are unknown.

In this sham-controlled trial, acupuncture helped reduce the occurrence and severity of xerostomia as early as 3 weeks into radiotherapy, with benefits remaining 1 month later. Based on these findings, future large-scale, multi-center, randomized placebo-controlled trials are indicated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support was provided in part by the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant CA121503 (PI L Cohen), the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672, and the Chinese Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality grant 05DZ19747 (PI Z Meng). We thank Drs. Peiying Yang, Zongxing Liao, and Jennifer McQuade for all their support with language, culture, and politics. Thank you to the Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for their helpful editorial comments on this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

References

- 1.Chambers MS, Rosenthal DI, Weber RS. Radiation-induced xerostomia. Head Neck. 2007;29(1):58–63. doi: 10.1002/hed.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong RK, Jones GW, Sagar SM, Babjak AF, Whelan T. A Phase I-II study in the use of acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation in the treatment of radiation-induced xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients treated with radical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(2):472–480. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertram U. Xerostomia. Clinical aspects, pathology and pathogenesis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1967;25(Suppl 49):1–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox PC, Van der Ven PF, Baum BJ, Mandel ID. Pilocarpine for the treatment of xerostomia associated with salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61(3):243–248. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenspan D, Daniels TE. Effectiveness of pilocarpine in postradiation xerostomia. Cancer. 1987;59(6):1123–1125. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870315)59:6<1123::aid-cncr2820590614>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson JT, Ferretti GA, Nethery WJ, Valdez IH, Fox PC, Ng D, et al. Oral pilocarpine for post-irradiation xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6):390–395. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308053290603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman RP, Mark RJ, Tran LM, Juillard GF. Concomitant pilocarpine during head and neck irradiation is associated with decreased posttreatment xerostomia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37(3):571–575. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horiot JC, Lipinski F, Schraub S, Maulard-Durdux C, Bensadoun RJ, Ardiet JM, et al. Post-radiation severe xerostomia relieved by pilocarpine: a prospective French cooperative study. Radiother Oncol. 2000;55(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brizel DM, Wasserman TH, Henke M, Strnad V, Rudat V, Monnier A, et al. Phase III randomized trial of amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(19):3339–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudat V, Meyer J, Momm F, Bendel M, Henke M, Strnad V, et al. Protective effect of amifostine on dental health after radiotherapy of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(5):1339–1343. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00768-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman T, Mackowiak JI, Brizel DM, Oster W, Zhang J, Peeples PJ, et al. Effect of amifostine on patient assessed clinical benefit in irradiated head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(4):1035–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00735-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindegaard JC, Grau C. Has the outlook improved for amifostine as a clinical radioprotector? Radiother Oncol. 2000;57(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha N, Seikaly H, Harris J, Williams D, Sultanem K, Hier M, et al. Phase III randomized study: oral pilocarpine versus submandibular salivary gland transfer protocol for the management of radiation-induced xerostomia. Head Neck. 2009;31(2):234–243. doi: 10.1002/hed.20961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rydholm M, Strang P. Acupuncture for patients in hospital-based home care suffering from xerostomia. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(4):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blom M, Lundeberg T. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with acupuncture for xerostomia and the influence of additional treatment. Oral Dis. 2000;6(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blom M, Dawidson I, Angmar-Mansson B. The effect of acupuncture on salivary flow rates in patients with xerostomia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blom M, Lundeberg T, Dawidson I, Angmar-Mansson B. Effects on local blood flux of acupuncture stimulation used to treat xerostomia in patients suffering from Sjogren's syndrome. J Oral Rehabil. 1993;20(5):541–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blom M, Dawidson I, Fernberg JO, Johnson G, Angmar-Mansson B. Acupuncture treatment of patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B(3):182–190. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawidson I, Blom M, Lundeberg T, Angmar-Mansson B. The influence of acupuncture on salivary flow rates in healthy subjects. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24(3):204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawidson I, Angmar-Mansson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. The influence of sensory stimulation (acupuncture) on the release of neuropeptides in the saliva of healthy subjects. Life Sci. 1998;63(8):659–674. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawidson I, Angmar-Mansson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) increases the release of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the saliva of xerostomia sufferers. Neuropeptides. 1998;32(6):543–548. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(98)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawidson I, Angmar-Mansson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) increases the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the saliva of xerostomia sufferers. Neuropeptides. 1999;33(3):244–250. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnstone PA, Peng YP, May BC, Inouye WS, Niemtzow RC. Acupuncture for pilocarpine-resistant xerostomia following radiotherapy for head and neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(2):353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnstone PA, Niemtzow RC, Riffenburgh RH. Acupuncture for xerostomia: clinical update. Cancer. 2002;94(4):1151–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnstone PA, Polston GR, Niemtzow RC, Martin PJ. Integration of acupuncture into the oncology clinic. Palliat Med. 2002;16(3):235–239. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm540oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho JH, Chung WK, Kang W, Choi SM, Cho CK, Son CG. Manual acupuncture improved quality of life in cancer patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(5):523–526. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng Z, Garcia MK, Hu C, Chiang J, Chambers M, Rosenthal DI, et al. Randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26550. (published online 9 NOV 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials: A practical Approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng L, Gan Y, He S, Ji X, et al. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deadman P, Al-Khafaji M, Baker K. A Manual of Acupuncture. East Sussex, England: Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park J, White A, Stevinson C, Ernst E, James M. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(4):168–174. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.4.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J. Sham needle control needs careful approach. Pain. 2004;109(1−2):195–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.010. author reply 197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, Ship JA. Xerostomia and its predictors following parotid-sparing irradiation of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(3):695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pacholke HD, Amdur RJ, Morris CG, Li JG, Dempsey JF, Hinerman RW, et al. Late xerostomia after intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus conventional radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28(4):351–358. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000158826.88179.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, Asper JA, Gning I, Kies MS, et al. Measuring head and neck cancer symptom burden: the development and validation of the M.D. Anderson symptom inventory, head and neck module. Head Neck. 2007;29(10):923–931. doi: 10.1002/hed.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia MK, Chiang JS, Cohen L, Liu M, Palmer JL, Rosenthal DI, et al. Acupuncture for radiation-induced xerostomia in patients with cancer: a pilot study. Head Neck. 2009;31(10):1360–1368. doi: 10.1002/hed.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Littell R, Milliken G, Stroup W, Wolfinger R, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models, Second Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisbruch A, Ten Haken RK, Kim HM, Marsh LH, Ship JA. Dose, volume, and function relationships in parotid salivary glands following conformal and intensity-modulated irradiation of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:577–587. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]