Abstract

Object

Low income, government insurance, and minority status are associated with delayed treatment for neurosurgery patients. Less is known about the influence of referral location and how socioeconomic factors and referral patterns evolve over time. For pediatric epilepsy surgery patients at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), this study determined how referral location and sociodemographic features have evolved over 25 years.

Methods

Children undergoing epilepsy neurosurgery at UCLA (453 patients) were classified by location of residence and compared with clinical epilepsy and sociodemographic factors.

Results

From 1986 to 2010, referrals from Southern California increased (+33%) and referrals from outside of California decreased (−19%). Over the same period, the number of patients with preferred provider organization (PPO) and health maintenance organization (HMO) insurance increased (+148% and +69%, respectively) and indemnity insurance decreased (−96%). Likewise, the number of Hispanics (+117%) and Asians (100%) increased and Caucasians/whites decreased (−24%). The number of insurance companies decreased from 52 carriers per 100 surgical patients in 1986–1990 to 19 per 100 in 2006–2010. Patients living in the Eastern US had a younger age at surgery (−46%), shorter intervals from seizure onset to referral for evaluation (−28%) and from presurgical evaluation to surgery (−61%) compared with patients from Southern California. The interval from seizure onset to evaluation was shorter (−33%) for patients from Los Angeles County compared with those living in non-California Western US states.

Conclusions

Referral locations evolved over 25 years at UCLA, with more cases coming from local regions; the percentage of minority patients also increased. The interval from seizures onset to surgery was shortest for patients living farthest from UCLA but still within the US. Geographic location and race/ethnicity was not associated with differences in becoming seizure free after epilepsy surgery in children.

Keywords: socioeconomic disparity, seizure, craniotomy, health inequity, epilepsy

SURGICAL and pediatric care in the US is influenced in part by socioeconomic factors.1,2,6,13 Studies find that patients from minority populations with reduced economic means have less access to subspecialty services and these patients have more complications and longer length of hospital stay than those from majority populations with private insurance. Access to surgical care is also a function of geographic availability for subspecialty services. A few studies have demonstrated disparities based on race or ethnicity and financial means for mostly adult epilepsy surgery.3,5,12,14 However, these studies have not routinely addressed whether practice patterns and referral have evolved over time.

This study was designed to determine if there were changes in sociodemographic variables over the 25-year history of the UCLA pediatric epilepsy surgery program. Pediatric epilepsy surgery patients were categorized by referral location within California and the US. Our goal was to ascertain how these variables changed over time and if they were linked with timing of referral, surgical outcomes, and other clinical epilepsy variables.

Methods

Cohort

The UCLA Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB#11–000030). Since enactment of HIPAA, patients or families have signed research informed consent forms and authorization forms. Prior to HIPAA, this study was considered exempt from requiring informed consent for research. This study is not a clinical trial.

The initial inclusion criteria were consecutive patients who underwent epilepsy neurosurgery involving resections at the UCLA Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Program from January 1986 to December 2010 (462 patients). By design, patients who underwent craniotomy without cortical resection (biopsy only), placement of diagnostic intracranial electrodes without resection, multiple subpial transections without cortical excision, or corpus callosotomy were excluded, leaving a final cohort of 453.

Clinical Variables

The presurgical clinical protocols, surgical procedures, and methods used to capture and catalog clinical epilepsy variables, surgical procedures, and outcome data, including operative complications, have been previously published.9,11,16 In brief, variables for research analysis included age at seizure onset, age at surgery, sex, history of infantile spasms, side of resection, and surgical procedure (defined as hemispherectomy, multilobar resection, or lobar/focal resection). Time to epilepsy surgery was calculated as the interval (in years) from age at seizure onset to age at surgery. Also calculated were the intervals from seizure onset to referral for presurgical evaluation and from referral for presurgical evaluation to surgery. Presurgery seizure frequency was dichotomously classified as daily versus less than daily. Based on the MRI and histopathological findings, etiology was ascertained as cortical dysplasia, hemimegalencephaly, acquired atrophic (ischemia, stroke, and infections), tumors, hippocampal sclerosis, Rasmussen syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, Sturge-Weber disease, vascular (cavernous angiomas), and nonspecific gliosis. Surgical complications consisted of death (operative and nonoperative), serious unanticipated permanent neurological deficits, and other severe adverse outcomes (for example, CSF leaks and infections).

Study Design

Patient medical records were reviewed and information on location of residence (based on home address), type of insurance, and race/ethnicity was abstracted. Information was obtained primarily from the encounter form, where each patient and family was asked by an administrative assistant their address of residence and ethnic category at the time of presurgical consultation and hospital admission. Location of residence was classified as Los Angeles County, Southern California (defined as from Fresno to Santa Barbara to the Mexican border excluding Los Angeles County), Northern California, Western US (defined as states west of the Mississippi River including Alaska and Hawaii but not California), Eastern US (states east of Mississippi River), and international. Race/ethnicity were classified as white (Caucasian), Hispanic, Asian, African-American, Middle Eastern, and mixed.

Data Analysis

StatView 5 (SAS Institute, Inc.) was used for statistical analysis. Student t-tests, ANOVA, and chi-square were used for univariate comparisons where appropriate. All tests were 2-tailed, and because of the multiple comparisons and large cohort size the threshold for significance was set a priori at p < 0.01.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

All 453 cases were assigned a referral location based on patient residence. The location categories were Los Angeles County (111 cases [25%]), Southern California (excluding Los Angeles County; 151 [33%]), Northern California (37 [8%]), Western US (110 [24%]), Eastern US (38 [8%]), and international (6 cases [1%]). Patients came from 16 states in the Western US and 20 states in the Eastern US. The most frequent states of residence outside of California were Nevada (22 cases), Arizona (14), Oregon (13), Washington (13), and Colorado (12). There were no cases from US Territories. Each of the 453 cases was assigned to one of 6 ethnicity categories: Caucasian/white (332 cases [73%]), Hispanic (86 [19%]), Asian (22 [5%]), African-American/black (7 [1.5%]), Middle East (4 [1%]), and mixed (2 [0.4%]).

Health insurance information was available in 443 cases (98%). There were 24 PPOs providing insurance for 171 patients (38%). Of these, Blue Cross was the most common, providing services for 77 (45%) of the 171 patients with PPO coverage. Two state government programs, California Children’s Services (n = 53) and MediCal (n = 33) provided 95% of the coverage for 91 cases (20%). The remaining 5 cases involved Medicaid (onetime contracts) from non-California states, and there were no cases where Medicare was the primary provider. There were 34 HMOs providing coverage for 81 patients (18%). Of these, Kaiser Permanente was the most frequent and provided coverage for 15 cases (18%). There were 48 companies providing indemnity insurance for 77 cases (17%), and no single company dominated this group. There were 23 self-pay cases (5%)—2 from Los Angeles County, 6 from Southern California, 2 from Northern California, 4 from the Western US, 3 from the Eastern US, and 6 international. In 10 cases (2%), insurance information was not available after an extensive review of the record. Due to small sample size, cases classified as international (n = 6) and those involving patients from the Middle East or classified as having mixed ethnicity (n = 6) were excluded from further analysis.

Referral Location Changes 1986–2010

There were dramatic changes in referral location over the 25 years of our program (Table 1, p < 0.0014). The proportion of cases from Southern California increased 33% from 1986 to 2010, and there was a onetime increase in patients from the Eastern US from 1991 to 1995. More patients from the Western and Eastern US had indemnity insurance compared with PPO coverage and California Children’s Services/MediCal for patients from Los Angeles County and Southern California. More Hispanic patients had California Children’s Services/MediCal compared with whites, who most often had PPO, HMO, and indemnity insurance. Most of our Hispanic patients came from Los Angeles County and Southern California compared with a higher percentage of whites from Northern California and Eastern and Western US (Table 2). International patients were mostly Asian and Middle Eastern.

TABLE 1.

Changes in location of patient residence over 25 years*

| Residence | 1986–90 (n = 60) | 1991–95 (n = 98) | 1996–00 (n = 55) | 2001–05 (n = 111) | 2006–10 (n = 129) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA Co (n = 111) | 28% (17) | 16% (16) | 27% (15) | 23% (26) | 28% (37) |

| S Cal† (n = 151) | 27% (16) | 21% (21) | 38% (21) | 41% (46) | 36% (47) |

| N Cal (n = 37) | 13% (8) | 13% (13) | 4% (2) | 3% (3) | 9% (11) |

| W US‡ (n = 110) | 25% (15) | 20% (20) | 27% (15) | 29% (32) | 22% (28) |

| E US (n = 38) | 7% (4) | 25% (23) | 4% (2) | 3% (3) | 5% (6) |

| int’l (n = 6) | 0% (0) | 5% (5) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) |

Chi-square, p < 0.0001; gray-shaded values are significant contributors. Abbreviations: E = Eastern; int’l = international; LA Co = Los Angeles County; N Cal = Northern California; S Cal = Southern California; W = Western.

Excluding Los Angeles County.

Excluding California.

TABLE 2.

Location of patient residence stratified by race/ethnicity*

| Race/Ethnic Category | LA Co (n = 111) | S Cal (n = 151) | N Cal (n = 37) | W US (n = 110) | E US (n = 38) | Int’l (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| white (n = 332) | 55% (62) | 67% (101) | 81% (30) | 93% (102) | 95% (36) | 17% (1) |

| Hispanic (n = 86) | 33% (37) | 24% (36) | 16% (6) | 4% (5) | 3% (1) | 17% (1) |

| Asian (n = 22) | 8% (9) | 5% (7) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 3% (1) | 50% (3) |

| African-Am (n = 7) | 1% (1) | 3% (5) | 3% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Middle Eastern (n = 4) | 2% (2) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 17% (1) |

| mixed (n = 2) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

Chi-square, p < 0.0001; gray-shaded values are significant contributors. Abbreviation: Am = American.

Comparison of Sociodemographic With Epilepsy Variables

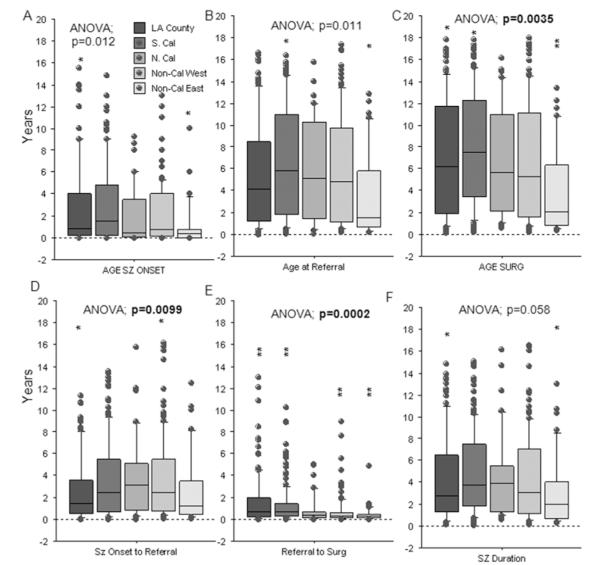

At UCLA, the duration of time from seizure onset to referral for evaluation and surgery was influenced in part by location of residence (Fig. 1). As there were changes from 1986 to 2010 (Table 1), a 2-way ANOVA incorporating time category as an independent variable was used for statistical comparisons for age and seizure intervals with sociodemographic variables.

Fig. 1.

Box plots by location of residence showing age at seizure onset (A), age at referral (B), age at surgery (C), time interval from seizure onset to referral for presurgical evaluation (D), interval from referral for evaluation to surgery (E), and seizure duration (interval from seizure onset to surgery, F). For referral location (A), age at seizure onset was younger for patients from the Eastern US (Non-Cal East) compared with Los Angeles County (LA County; *post hoc; p = 0.010). Age at referral (B) was younger for patients from the Eastern US compared with those from Southern California (S. Cal; *p = 0.009). Age at surgery was younger for patients from the Eastern US compared with those from Los Angeles County (*p = 0.0074) and Southern California (*p = 0.0016). The interval from seizure onset to referral (D) was shorter for patients from Los Angeles County than those in the Western US other than California (Non-Cal West; *p = 0.010). The interval from referral for evaluation to surgery (E) was shorter for patients from the Western US and Eastern US compared with those from Los Angeles County and Southern California (**p < 0.0097). Seizure duration (F) was shorter for patients from the Eastern US compared with those from Los Angeles County (*p = 0.010). N. Cal = Northern California; SURG = surgery; SZ = seizure.

By location of residence, patients from the Eastern US had a younger at age at seizure onset (Fig. 1A, asterisks), age at referral for evaluation (Fig. 1B), and age at surgery (Fig. 1C) compared with patients from Los Angeles County and Southern California. In addition, patients from the Eastern US had shorter intervals from referral for evaluation to surgery (Fig. 1E) and seizure duration (seizure onset to surgery; Fig. 1F) compared with patients from other geographic locations. By comparison, the interval from seizure onset to referral for evaluation was shorter for patients from Los Angeles County compared those from the Western US (Fig. 1D). Other epilepsy variables, including type of operation, etiology, percentage of patients who were seizure free up to 5 years postsurgery, use of AEDs after surgery, and complications were not different based on referral location (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Clinical epilepsy variables by geographic area of residence of pediatric patients referred to UCLA for epilepsy surgery*

| Clinical Variable | LA Co (n = 111) | S Cal (n = 151) | N Cal (n = 37) | W US (n = 110) | E US (n = 38) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| female (n = 213) | 45% (50) | 49% (74) | 35% (13) | 49% (54) | 55% (21) | 0.429 |

| left handed (n = 231) | 49% (54) | 50% (76) | 62% (23) | 49% (54) | 58% (22) | 0.538 |

| Hx of infantile spasms (n = 148) | 26% (29) | 31% (47) | 33% (12) | 31% (35) | 55% (21) | 0.026 |

| daily seizures (n = 354) | 78% (86) | 77% (114) | 86% (32) | 75% (83) | 92% (35) | 0.469 |

| operation | 0.105 | |||||

| hemi (n = 189) | 40% (45) | 41% (59) | 43% (16) | 45% (49) | 49% (18) | |

| multilobar (n = 70) | 11% (12) | 14% (22) | 19% (7) | 16% (17) | 30% (11) | |

| lobar/focal (n = 187) | 49% (54 | 45% (60) | 38% (14) | 39% (43) | 21% (8) | |

| etiology | 0.156 | |||||

| cortical dys (n = 160) | 34% (35) | 26% (37) | 60% (20) | 41% (44) | 60% (21) | |

| atrophy (n = 58) | 14% (15) | 14% (21) | 9% (3) | 13% (19) | 14% (5) | |

| hipp scl (n = 35) | 10% (10) | 8% (11) | 6% (2) | 10% (11) | 0% (0) | |

| HME (n = 32) | 7% (7) | 8% (11) | 9% (3) | 8% (8) | 9% (3) | |

| Ras enceph (n = 38) | 11% (11) | 9% (13) | 9% (3) | 9% (9) | 6% (2) | |

| tumor (n = 38) | 10% (10) | 12% (17) | 6% (2) | 8% (8) | 3% (1) | |

| infection (n = 17) | 4% (4) | 7% (10) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 3% (1) | |

| TSC (n = 26) | 8% (8) | 10% (14) | 0% (0) | 3% (3) | 3% (1) | |

| non-Dx (n = 23) | 4% (4) | 7% (10) | 3% (1) | 7% (7) | 3% (1) | |

| seizure free | ||||||

| 0.5 yr (328/423) | 96% (88) | 94% (104) | 92% (26) | 95% (83) | 92% (23) | 0.725 |

| 1 yr (292/388) | 91% (76) | 90% (99) | 83% (21) | 87% (73) | 89% (19) | 0.742 |

| 2 yr (238/329) | 84% (65) | 76% (77) | 79% (16) | 81% (58) | 83% (18) | 0.567 |

| 5 yr (149/244) | 75% (43) | 68% (46) | 85% (8) | 68% (38) | 72% (11) | 0.437 |

| off AEDs last FU visit (104/402) | 32% (33) | 25% (33) | 22% (7) | 22% (22) | 23% (7) | 0.495 |

| complications (n = 37) | 8% (9) | 9% (13) | 11% (4) | 7% (8) | 5% (2) | 0.921 |

cortical dys = cortical dysplasia; FU = follow-up; hemi = hemispherectomy; hipp scl = hippocampal sclerosis; HME = hemimegalencephaly; Hx = history; non-Dx = nondiagnostic histopathology and normal MRI findings; Ras enceph = Rasmussen encephalitis; TSC = tuberous sclerosis complex.

Discussion

This study documents the evolving patterns of patients’ location of residence, insurance type, and race/ethnicity from 1986 to 2010 at a single pediatric epilepsy surgery center in the southwestern US. We found that geographic location of referral influenced timing for pediatric epilepsy surgery, with a reduction in referrals from the longest distances over time.15 In Italy, it was noted that increased proximity of a referring neurologist’s practice to an epilepsy surgery center seemed to increase the likelihood of referring patients for an comprehensive epilepsy evaluation.7 Hence, at least one prior study has shown that location of residence is associated with timing of referral for evaluation for adult epilepsy surgery patients. However, similar studies have not addressed these questions for pediatric epilepsy surgery.

Our study found that geographic location of residence influenced the timing of referral for evaluation and surgery at UCLA. It might seem paradoxical that those coming from longer distances, like the Eastern US, had shorter intervals from seizure onset to referral for presurgical evaluation and surgery than patients from Los Angeles and Southern California. This can probably be explained by why and when these patients came to UCLA (Fig. 1). Patients from the Eastern US, who came most often from 1991 to 1995, when the program was first nationally recognized for treatment of children with infantile spasms, were likely motivated by the possibility of surgical treatment for this condition. This is supported by the finding that 55% of patients from the Eastern US had a history of infantile spasms compared with less than 33% for all other geographic regions (Table 3). Also, 1991–1995 was a period when there were fewer pediatric epilepsy surgery centers in the East. This may explain why patients were referred by physicians or referred themselves for possible epilepsy neurosurgery. Because families were coming from longer distances, the evaluation and treatment process was compressed into a single trip, which was a standard part of our protocol at UCLA. It is suggested that future studies may need to take into consideration the evolution of subspecialty care in the US and the number of centers offering that care in determining the influence of sociodemographic factors in subspecialty surgical care.

It is equally important to understand that most of the sociodemographic variables assessed in our study were not associated with types of operations, etiologies, and seizure-free outcomes after surgery in children. This is similar to findings previously reported for adult patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.4,5

This study has limitations the reader should be aware of. For example, differences in the interval from seizure onset to surgery by location of residence could be influenced by strongly linked cofactors such as educational and income levels of families, race, language barriers, and patient and doctor attitudes toward surgical treatment.7,8 Furthermore, it is unclear if our experience at UCLA will be unique or similar to the experience at other centers without information from other long-standing pediatric epilepsy surgery programs. It is also unclear how factors such as insurance contracting might influence referral patterns. These and other factors should be considered in future studies trying to determine which sociodemographic factors are involved in the timing of referral for subspecialty pediatric epilepsy surgery services.

Conclusions

This study shows that socioeconomic and demographic factors were not static but changed substantially over a 25-year period for pediatric epilepsy surgery patients at a single center in the Southwest US. Over time, there were more referrals from Southern California and from minority populations and there were fewer insurance companies. The intervals from seizure onset to evaluation and surgery were shorter for patients from the farthest region, the Eastern US. Such findings support the concept that there might be delays in accessing subspecialty neurosurgical care, such as pediatric epilepsy surgery, and that these delays might be influenced in part by location of residence relative to provider centers. Socioeconomic and demographic factors along with known clinical variables should be considered in future studies identifying inequities in referral for epilepsy surgery.10

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of the following individuals over the lifetime of this program: Alan Shewmon, M.D., Harry Chugani, M.D., Ph.D., W. Donald Shield, M.D., Joyce Wu, M.D., Joyce Matsumoto, M.D., Jason Lerner, M.D., Youseff Comair, M.D., Warwick Peacock, M.D., Christopher C. Giza, M.D., and Susan Koh, M.D.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- HIPAA

the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- PPO

preferred provider organization

- UCLA

University of California, Los Angeles

Footnotes

Disclosure Dr. Baca receives salary support from the Epilepsy Foundation Grant 213971. Dr. Vickrey serves on scientific advisory boards for the Sports Concussion Institute, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the NIH; serves on the editorial boards of Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair and Circulation, Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, and is a section editor for Stroke; receives research support from the NIH (National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke), the US Veterans Administration Health Services Research and Development Service, the American Heart Association, and SCAN Foundation; and received funding for travel and a speaker honorarium from the Kansas City Area Life Sciences Institute. Dr. Sankar serves on scientific advisory boards for and has received honoraria and funding for travel from UCB Pharma, Sunovion, Upsher-Smith, Supernus, and Lundbeck Pharma; receives royalties from the publication of Pediatric Neurology, 3rd ed. (Demos Publishing, 2008) and Epilepsy: Mechanisms, Models, and Translational Perspectives (CRC Press, 2011); serves on speakers’ bureaus for and has received speaker honoraria from UCB, GlaxoSmithKline, and Lundbeck. He receives funding from NIH-MH079933 (co–primary investigator) and from Pfizer (Lyrica pediatric partial seizures trial). He serves on the editorial board for Epilepsy & Behavior. Dr. Vinters is on the editorial boards of Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, Neuropathology, Journal of Neuroscience Research, and the Korean Journal of Pathology. The Harry V. Vinters laboratory was supported in part by the University of California Pediatric Neuropathology Consortium, and Harry V. Vinters trust owns shares in and receives dividends from the following makers of drugs and medical equipment: GE, 3M, Pfizer, Teva Pharma, and GlaxoSmithKline. The Vinters laboratory has received research funding in the past from NeuroPace, Inc. Dr. Mathern received research funding from NIH grant R01 NS38992, which partially supported this paper. He is also on the editorial boards for Neurology, Epilepsy Research, Epileptic Disorders, and Epilepsy & Seizures. He serves on the Data Management Committee for NeuroPace, Inc.

Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation include the following. Conception and design: Mathern, Baca. Acquisition of data: Hauptman, Dadour, Oh, Salamon. Analysis and interpretation of data: Mathern, Baca, Vickrey, Vassar. Drafting the article: Mathern, Hauptman, Baca, Vickrey, Vinters. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Mathern. Statistical analysis: Mathern, Vassar.

References

- 1.Abbott MM, Kokorowski PJ, Meara JG. Timeliness of surgical care in children with special health care needs: delayed palate repair for publicly insured and minority children with cleft palate. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2324–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burneo JG, Black L, Martin R, Devinsky O, Pacia S, Faught E, et al. Race/ethnicity, sex, and socioeconomic status as predictors of outcome after surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1106–1110. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.8.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burneo JG, Jette N, Theodore W, Begley C, Parko K, Thurman DJ, et al. Disparities in epilepsy: report of a systematic review by the North American Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2285–2295. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burneo JG, Knowlton RC, Martin R, Faught RE, Kuzniecky RI. Race/ethnicity: a predictor of temporal lobe epilepsy surgery outcome? Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS, Barker FG., II Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in patient outcomes after craniotomy for tumor in adult patients in the United States, 1988-2004. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:427–438. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000365265.10141.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erba G, Moja L, Beghi E, Messina P, Pupillo E. Barriers toward epilepsy surgery. A survey among practicing neurologists. Epilepsia. 2012;53:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haneef Z, Stern J, Dewar S, Engel J., Jr Referral pattern for epilepsy surgery after evidence-based recommendations: a retrospective study. Neurology. 2010;75:699–704. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemb M, Velasco TR, Parnes MS, Wu JY, Lerner JT, Matsumoto JH, et al. Improved outcomes in pediatric epilepsy surgery: the UCLA experience, 1986-2008. Neurology. 2010;74:1768–1775. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e0f17a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas R, Asarnow RF, LoPresti C, Yudovin S, Koh S, Wu JY, et al. Surgery for symptomatic infant-onset epileptic encephalopathy with and without infantile spasms. Neurology. 2005;64:746–750. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151970.29205.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonas R, Nguyen S, Hu B, Asarnow RF, LoPresti C, Curtiss S, et al. Cerebral hemispherectomy: hospital course, seizure, developmental, language, and motor outcomes. Neurology. 2004;62:1712–1721. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127109.14569.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee D, Carico C, Nuño M, Patil CG. Predictors of inpatient complications and outcomes following surgical resection of hypothalamic hamartomas. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:105. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.83387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee D, Kosztowski T, Zaidi HA, Jallo G, Carson BS, Chang DC, et al. Disparities in access to pediatric neurooncological surgery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e688–e696. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szaflarski M, Szaflarski JP, Privitera MD, Ficker DM, Horner RD. Racial/ethnic disparities in the treatment of epilepsy: what do we know? What do we need to know? Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9:243–264. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiebe S, Camfield P, Jetté N, Burneo JG. Epidemiology of epilepsy: prevalence, impact, comorbidity and disparities. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(Suppl 2):S7–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JY, Salamon N, Kirsch HE, Mantle MM, Nagarajan SS, Kurelowech L, et al. Noninvasive testing, early surgery, and seizure freedom in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2010;74:392–398. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ce5d9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]